Question: Reference: On May 3, 2016, Thomas Andrews, a young investment banker, was examining the current situation of ChimpChange Limited (ChimpChange), a financial technology (fintech) start-up

Reference:

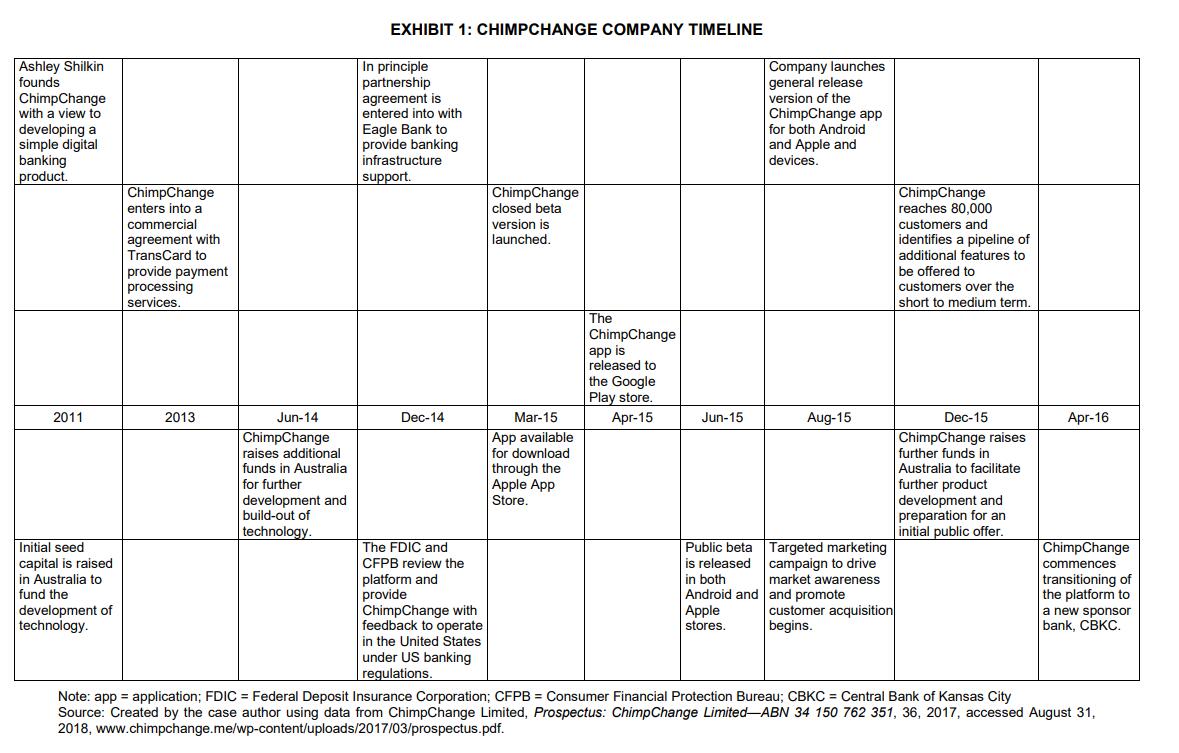

On May 3, 2016, Thomas Andrews, a young investment banker, was examining the current situation of ChimpChange Limited (ChimpChange), a financial technology (fintech) start-up based in California. After working to develop the necessary platform, establish the required banking relationships, and obtain regulatory approvals, ChimpChange had launched the general-release version of its application (app) and started full operations in August 2015 (see Exhibit 1). Within the first nine months, the company already had 80,000 customers, but it needed more to reach its break-even point.

ChimpChange was positioned as a credible disruptor to the status quo in the banking industry; it had a strong value proposition and was poised for growth. To attain sufficient scale to be profitable required significant investments in customer acquisition, and the company still had a negative cash flow. The company was not projected to break even until it had about 250,000 customers. ChimpChange had already completed several rounds of financing to get it through the software development and regulatory approval stages. These financing rounds included investments from friends and family, angel investors, and venture capitalists (VCs). Although these investments had provided the company with the capital to get to this point, they had also required it to give up a large degree of control (through both ownership and positions on the board). Andrews wondered what would be the best way for the company to raise the necessary funding to achieve its objectives. The alternatives included either a series C funding round or the completion of an initial public offering (IPO) to raise the funds needed to both pay for operational expenses and the marketing to acquire the customers necessary for the firm to reach the break-even point. Determining the best way to raise this capital was not easy. It was important to carefully weigh all of the options, as any decision could have implications that would extend far into the future.

DISRUPTION IN THE BANKING INDUSTRY

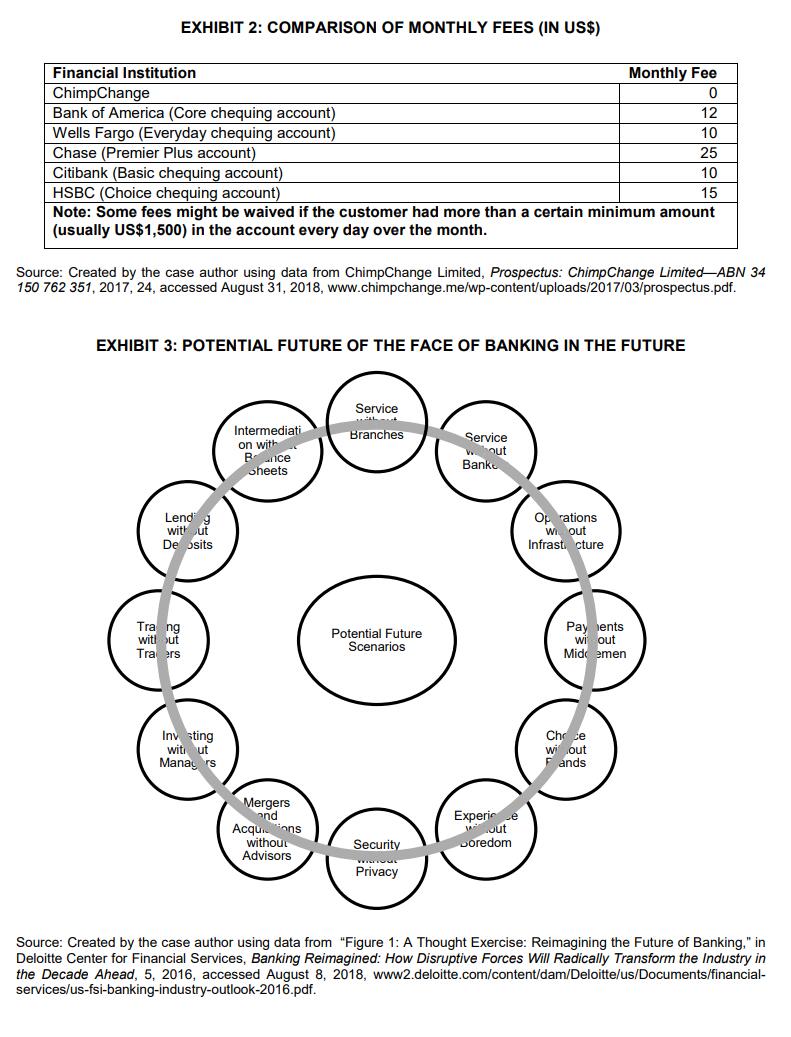

Few people questioned the idea that the banking industry would look quite different by 2025. The traditional banking model was being challenged from all sides. Traditionally, banks were large buildings that inspired confidence and made customers feel safe leaving their money there until they needed it. Consequently, banks were places where people saved money, and they got chequing accounts so they could access their money to pay bills. If they needed more money than they had saved, they could go to the bank to get a loan. Banks made money from the difference between the interest they paid on deposits or chequing accounts and the interest they earned on loans, as well as from fees for other financial and advisory services (see Exhibit 2).

More recently, banks had branched out into offering different services and products to increase their fees and trading incomes. In fact, some of these products and practices were believed to have led to the global financial crisis in 2008. As a result, banks?which had been among the most trusted brands before the financial crisis?were now listed within the top 10 least trusted brands by millennials. This change in the level of trust enjoyed by banks had allowed for the disruption of the banking industry by entrants who could offer basic banking services at lower prices. Many of these competitors were part of the technology movement called fintech.

FINTECH

Fintech was an emerging financial services sector that relied on technology-based solutions to execute financial transactions in a manner similar to banks, but with lower costs. Since the Internet revolution, fintech had grown explosively and now included a broad variety of apps for personal and commercial finance. Because these firms often offered services similar to those of traditional banks, fintech innovations were viewed as disruptors that affected traditional financial institutions.

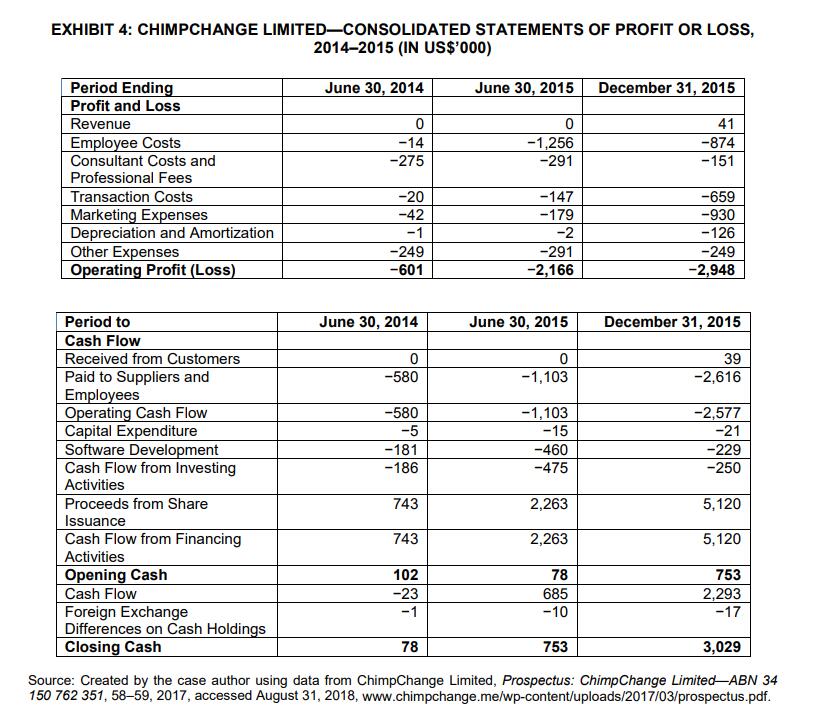

The large margins in financial services had attracted many small companies, and this resulted in the fintech sector receiving significant investor interest: start-ups received $17.4 billion in funding in 2016 and were expected to receive even more in 2017, according to Forbes. By 2016, it was estimated that there were over 20 fintech unicorns globally, valued at a total of $83.8 billion. Due to the large margins in banking in North America, this region produced most of the fintech start-ups, followed by Asia. Some of the most active areas of fintech innovation included (1) cryptocurrency; (2) blockchain or distributed ledger technology; (3) "insurtech" or insurance technology, to streamline insurance; (4) "regtech" or regulation technology, to meet industry compliance rules; (5) robo-advisors; and (6) cybersecurity. Fintech was able to influence the financial services industry (see Exhibit 3), and a main target of fintech firms were members of the millennial generation.

Millennials

Millennials were individuals born between 1980 and 2000. They were the largest demographic in the United States, with 92.2 million people or 28 per cent of the total US population. Millennials were the first generation to grow up using the Internet, mobile technologies, and social media to conduct transactions and share their opinions and experiences. As a result, they were very comfortable using technology in all aspects of their lives. When Viacom Media Network surveyed Americans to study the differences between millennials and other generations in the United States, one of its most striking findings was that, in the United States, the banking and financial services industry was identified as the industry most likely to experience a change as a result of the increasing power of this generation. It also noted the following key findings: (1) all four of the leading banks in the United States were among the 10 brands least loved by millennials; (2) 33 per cent of respondents believed that they did not require the services of a bank; (3) nearly half of millennials were relying on start-ups to overhaul banks and their service offerings; (4) 70 per cent of millennials anticipated that the way they would access their money and pay for items would be completely different in five years' time; (5) 38 per cent of millennials did not use traditional bank branch networks, and more than one-quarter visited a branch less than once per year; and (6) 90 per cent of U.S. millennials used digital banking methods, including online banking and banking on mobile devices, for executing day-to-day transactions.

This made the millennials an ideal target group for fintech disruptors such as ChimpChange. Millennials may have not liked banks, but they did need them. As of 2013, it was estimated that 20 per cent of US households were "underbanked" (i.e., they did not have sufficient access to standard banking services such as credit cards, bank loans, and other retail banking products). For example, about 30 per cent of the underbanked households did not have savings accounts. Even though underbanked households did not have bank accounts, 90.5 per cent of this group was likely to have access to mobile phones and 64.5 per cent was likely to have access to smart phones, compared with 59 per cent of fully banked households. "Underbanked households were also considerably more likely (32.4 per cent) than the fully banked (21.6 per cent) to use mobile banking as their main banking method."

HISTORY OF CHIMPCHANGE

In 2013, Ashley Shilkin began to work on a business model that would provide low-cost banking services to underserved groups. He had a vision that banking could be done differently, and this resulted in the founding of ChimpChange. At the time, he was the chief financial officer (CFO) of CO2 Australia Limited, a company that he helped grow from AU$30 million to AU$300 million over a five-year period. After being unable to secure a partnership with any of the few large players that dominated the Australian banking industry, Shilkin travelled to the United States to pursue the idea there:

As I vacationed to the U.S., I particularly saw a multitude of problems which I thought didn't need to exist. I asked myself why banks charge high monthly account keeping fees to such a huge portion of the population, why overdraft fees are so high, why it costs $25 to wire transfer someone money domestically and it still takes overnight. Finally, I asked myself why bank accounts have failed to incorporate technology to add more value to the customer user experience. My gut told me there must be a better way, so I quit my job and dedicated my life to find it.

Shilkin quit his job in 2013 and moved to Los Angeles to pursue his idea. With money from family and friends and the financial support of an angel investor, his former CEO at CO2, Shilkin spent two years developing the ChimpChange platform and establishing all of the necessary relationships with financial institutions and regulators.

ChimpChange's value proposition was based on addressing two of the main pillars required to succeed in banking: price and analytics. Many people in Shilkin's target market were "middle to low income earners, who are being charged $10-$20 in monthly account keeping fees plus overdraft fees by their bank." ChimpChange wanted to address the first pillar by launching a service that would not charge monthly fees (see Exhibit 2). For the second pillar, it would provide many of the services not provided by the standard banks to enhance the customers' experience.

POSITIONING

ChimpChange developed a digital banking platform specifically targeted to millennials as "a digital alternative to high cost and rigid traditional retail banking offerings." The platform allowed customers to establish bank accounts insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and to make instant peerto-peer transfers. The company also issued a branded debit Mastercard, which allowed customers to deposit and withdraw funds at retail stores and at 24,000 automated teller machines (ATMs) across the United States. ChimpChange's business model generated revenues through interchange fees, network ATM fees, and other platform fees such as cheque clearing, budgeting tools, foreign exchange, and bill payments.

Through its early stages (before June 2014), the company had received seed financing from friends and family, as well as an angel investor who purchased almost 18 million shares, helping the company raise $1.1 million. This led to an implied share price of $0.06. In November 2014 and February 2015, the same individuals were approached again as the idea progressed and more capital was needed to develop the platform. In total, another $1.5 million was raised at implied share prices of $0.23 and $0.31, respectively. In July 2015, before the official release of the app, the company raised a further $2.265 million at an implied share price of $0.41 through a series A round of funding from venture capital firms. This money was to help attract new customers and pay for finishing the app. ChimpChange was now able to access VCs because it had cash inflows from the beta version of the app.

Despite launching only the general-release version of its app in August 2015, ChimpChange had over 80,000 customers within the first nine months. Shilkin needed more customers; if he could triple the number of clients by the end of 2017, the company would reach its break-even point. To achieve this, ChimpChange developed a marketing budget of $100,000-$200,000 per month. Early signs showed that the average customer acquisition cost (CAC) was well below the budgeted level of $25 per customer and considerably less than the industry average. To move in this direction, the company underwent a series B round of fundraising from VC firms for $4.033 million in December 2015. Operations were starting and money was needed to execute transactions and to cover operating costs, customer acquisitions, and further product development. The implied share price of this funding round was $0.51.

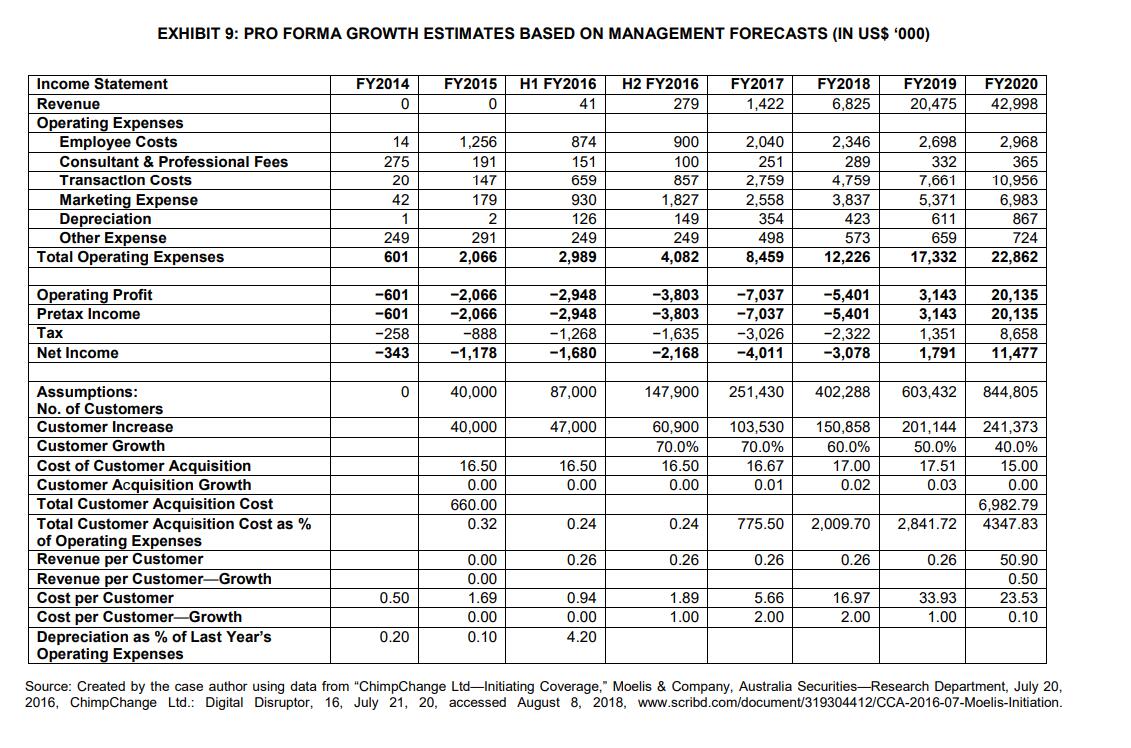

With some revenue being generated and with increasing experience in customer acquisition, it was now possible to make some forecasts for the future. Specifically, ChimpChange had originally budgeted for an average CAC of $25.00 per user but had spent only $16.50 per customer through the end of 2015, and this figure been decreasing through early 2016. It was forecasted to go down to $15.00, where it was expected to stay over the next 10 years. The CAC for ChimpChange was interestingly low when compared to the CAC for traditional financial services firms, which often ranged $1,500-$2,000 per retail customer. It was much lower for fintech firms, where it ranged $5-$300 per user. Shilkin and his team were telling the market that they expected their total customer base to approach 250,000 (the number of users at which the company could attain its cash-flow break-even point) by the end of 2017. Although the growth rate in customer acquisition would slow gradually over the next five to seven years, it was expected to reach 1.5 million customers within 10 years. As of May 2016, after including all of the necessary expenses to make it to the break-even point, management estimated that the company's marketing budget would need to be $12 million to execute the growth strategy to get them to the next level.

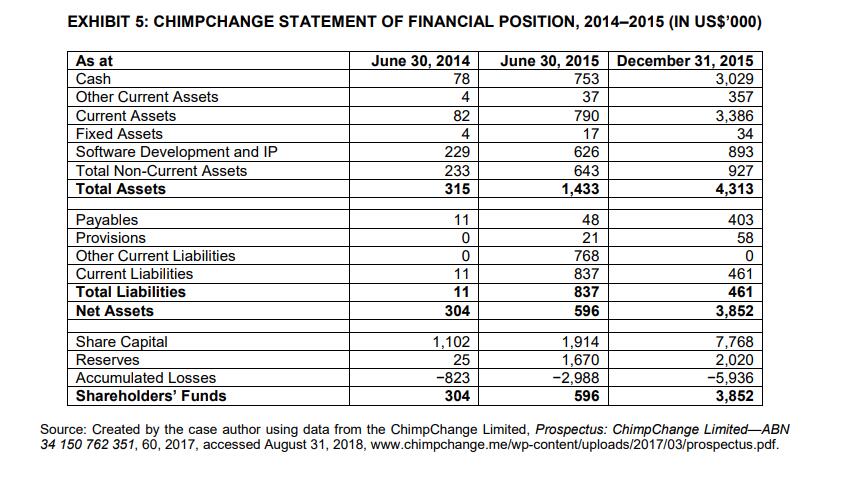

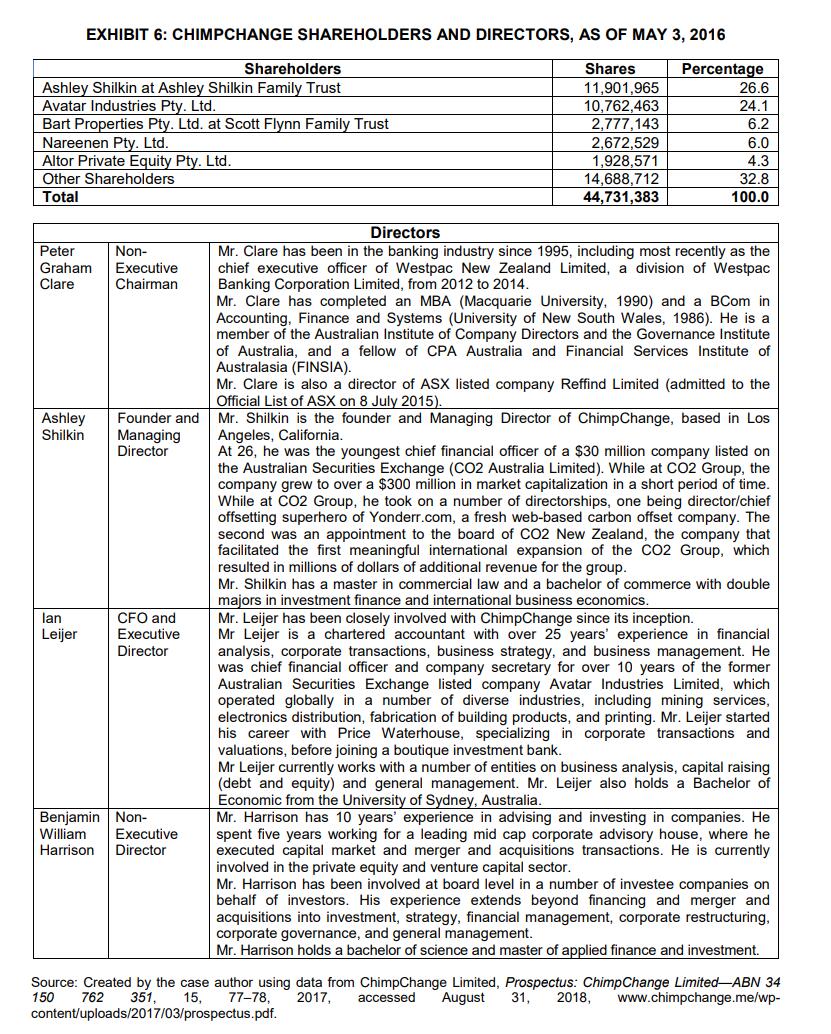

The current financials indicated that the firm would be out of cash in less than one year under current conditions, so the company needed to access capital quickly (see Exhibits 4 and 5). Burning cash at this rate was not unusual for technology firms in the early stages of their growth, so it was unlikely that investors would view ChimpChange's financial situation as a concern. However, ChimpChange did need to access further capital and consider the pros and cons of the different potential sources of capital. Its largest current shareholder and original angel investor was very supportive of the direction being taken and gave his approval for this next step. As was typical for angel investors, however, he was now interested in decreasing his 47 per cent position to less than 20 per cent in order to realize some return from his investment, and other investors were interested in decreasing his control.

Consequently, Shilkin had to consider other potential sources of capital. Approaching the company's current financial partners (e.g., venture capital funders) was an option, but this would mean these partners, who already had representatives in both senior management positions and on the board, would obtain more control and an even stronger voice on the board (see Exhibit 6). The company could approach strategic partners, but Australian banks had not been very interested earlier. Would Australian or U.S. banks be interested now that the company had moved beyond the proof of concept stage? Shilkin could also consider raising money through a public listing, or IPO, in either Australia or the United States.

The amount of required capital was known, but an important consideration was how much of the firm would have to be sold to raise that capital. The valuation would depend on many different factors, so a key question future investors would want to understand involved the competitive environment and risks that ChimpChange would be facing in trying to implement its business model and grow.

COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT

As a disruptor in an industry with large incumbents and many barriers to entry, ChimpChange operated in an environment with many competitive risks. Most importantly, incumbent financial institutions had strong customer relationships and broad product portfolios, making it important for new entrants to clearly identify their points of differentiation. New entrants all had low barriers to entry and limited product portfolios and were chasing the same customer base, so newer entrants generally competed on price. The primary risks to ChimpChange related to its rate of customer acquisition, the volume of use of its platform, potential losses of customers to competing platforms, the strength of its partner relationships, research and development, regulations, and cybersecurity regarding customer information.

ChimpChange experienced moderate industry rivalry, as a low but increasing number of pure-play digital banks were entering the market. Traditional banks had historically underserved low-value accounts, such as those of the millennials ChimpChange was targeting, due to the limited profit opportunities associated with these accounts. However, with the advent of fintech app solutions, traditional banks were increasingly acknowledging this market segment. As technology enabled start-ups and new platforms to attain scale rapidly, the threat of new entrants was high. Overall, this was a large, underserved market (there were about 92 million millennials in the United States alone) with large competitive pressures.

Increased adoption of functions like Apple Pay and Google Wallet could increase the attraction of services like ChimpChange, as the ease of syncing debit cards and mobile apps attracted users. Supplier inputs included sponsor bank and payment processing partners, both of whom had alternative players, who largely competed on a price basis. Switching costs to buyers (bank customers) were typically high from an effort and logistical viewpoint, but buyers bore very low financial costs in establishing new bank accounts. Accordingly, customers could typically demand higher savings rates, lower lending rates, and better functionality.

Some of the advantages ChimpChange had in this space included a first-mover advantage and a growing customer base. Its platform and business models were operational and were demonstrating their scalability, allowing for a forecast of break-even status in a year or so. This was a large market with many potential customers, but the customers could be very willing to change service providers.

RAISING CAPITAL

A first step to determining how to raise the required $12 million was to consider the valuation the company would receive by accessing different types of capital. Although completing an IPO could raise the largest amount of capital?and likely at the highest valuation?it would come with many constraints due to the requirements for disclosure and compliance for a publicly listed company. Raising capital through either VCs or a strategic partner would require giving up more control, but it would require less disclosure and it could provide important advice. The company and its investors were familiar with these trade-offs as ChimpChange had experience with several different means of raising capital over its short lifetime.

One of the major issues with raising capital for a high-growth start-up was its valuation. How would VC or private equity (PE) investors value the firm? Would their valuation be different than that of an IPO? Would it depend on the listing exchange? It was important to estimate the value for ChimpChange under the different alternatives before moving forward with raising capital, both to understand the value to shareholders of the firm and to estimate the amount of the firm that would have to be sold to raise the required $12 million.

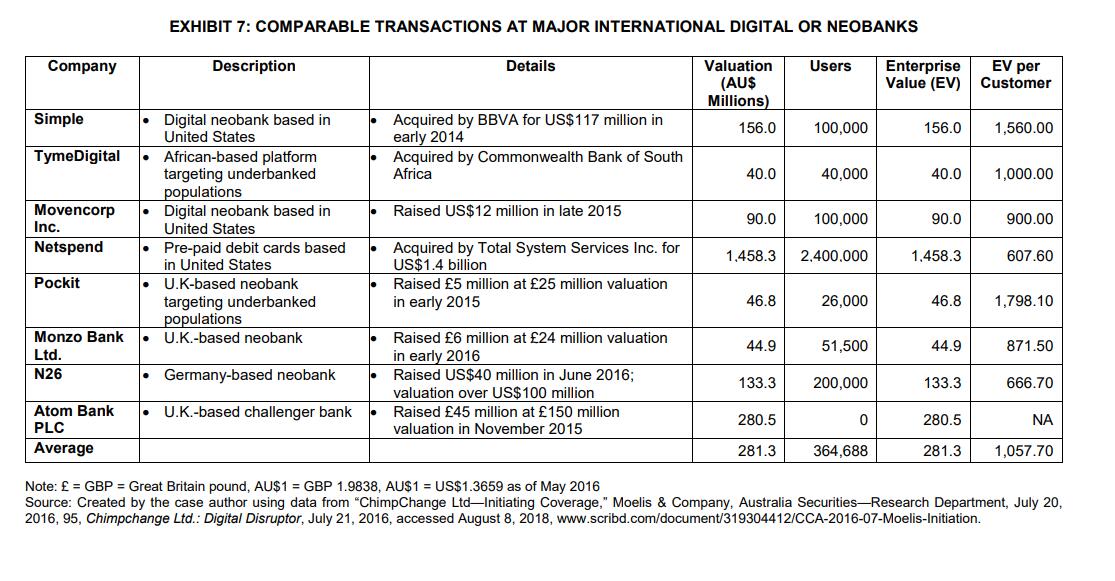

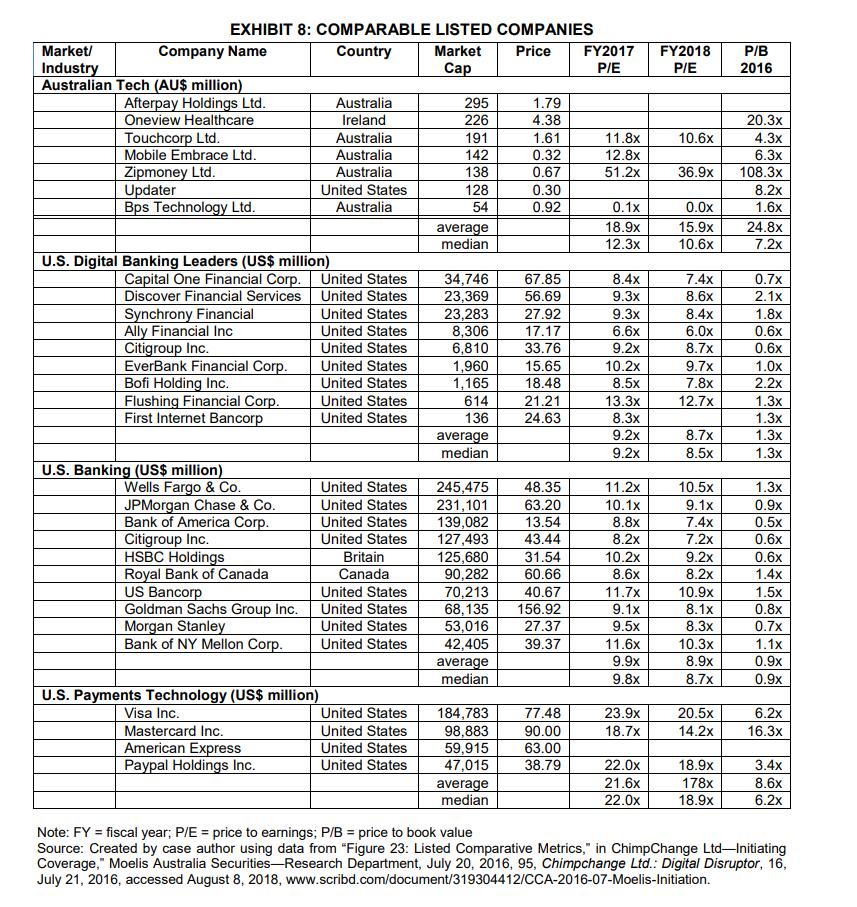

A natural starting point was to consider how much investors had paid for similar firms in this industry, and this would provide a nice benchmark for ChimpChange's current value. Most comparable firms were being valued on a per-customer basis. The lifetime customer value of a low to medium saver for a traditional bank ranged between $3,000 and $7,500 and could be significantly higher, depending on the other services the customers used. ChimpChange offered only chequing and savings accounts, so the lifetime customer value would be considerably lower for ChimpChange (see Exhibit 7). For example, Simple Finance Technology Corp. was acquired for an average price of $1,560 per customer, which was broken down as $1,200 per user $3,300 per active user. Similarly, ChimpChange could look at comparable firms' valuations on different stock exchanges (see Exhibit 8)

Because ChimpChange was located in the United States and Shilkin and many of his initial investors were Australian, it was natural to consider listing on either the Nasdaq Stock Market (Nasdaq) in the United States or the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). The ASX was striving to become the location for small- and medium-sized firms to launch their IPOs and was becoming a natural stepping stone to listings on the Nasdaq or Hong Kong exchanges.

Over the previous five years, the ASX had been called the "Nasdaq of Asia Pacific" after nearly doubling its technology listings. The ASX had 224 technology companies listed with a market capitalization of AU$69 billion ($55 billion). The ASX had been able to position itself as a technology leader because there was no Nasdaq-type technology exchange in the Asia-Pacific region, and technology and innovation had exploded in the region. Other major exchanges in the region, in particular the Hong Kong and Singapore exchanges, had marketed themselves as leaders in the technology space by being more corporate-governance friendly, but were focused on larger firms. ASX's strategy was to target tech companies with small to medium capitalization, worth under $1 billion. As a result, the ASX had attracted companies from Ireland, New Zealand, Israel, Germany, Singapore, Malaysia, and the United States, as well as a growing number of domestic technology companies.

Valuation

Valuing a company at such an early stage in its development was difficult. Although there were two and a half years of operating history for ChimpChange, and the company had acquired over 80,000 customers in its first nine months, it had only $41,000 in revenues. The reason for the low revenue figure was that only 25 per cent of the company's customers had taken debit cards. ChimpChange customers could open debit card accounts once they felt comfortable with the platform, but that would take time. If customers used their ChimpChange debit cards within three years, it would earn the company between $3 and $4 per month per customer. As more services were added, this per-customer revenue was expected to increase over the subsequent five to seven years, likely growing to about $7-$8 per month over this period.

Assuming that ChimpChange continued to attract customers, within 10 years, it would have close to 1.5 million customers. Customer acquisition costs were expected to remain at $15 per customer for the next year. They were then expected to increase at an increasing rate up to an increase of 5 per cent per year in 5 years. The annual growth rate in acquisition costs was assumed to remain at 5 per cent for the next 10 years as it became increasingly difficult to acquire new customers. Many of the company's other costs, such as overhead costs for head office employees and professional fees, would grow at a rate similar to the customer growth rate. However, transaction costs per customer would increase slightly more rapidly as ChimpChange was expected to offer more services to its clients. These services would require increased costs per customer, which would partially offset the increased revenues from these services. The annual transaction costs per customer were expected to grow from $7 at the end of 2016 to $25 within five years and $30 within 10 years (see Exhibit 9).

Another major component to consider in estimating the value of ChimpChange was its cost of capital. While it was difficult to find comparable companies, most companies in this sector had a beta in the range between 1.2 and 1.5.

DECISION

With all of the necessary information in front of him, Andrews wanted to determine how ChimpChange could fund the necessary growth in customers. Raising AU$15 million or US$12 million, depending on the location, would require giving up some control. How much control would the company have to give up? What were the pros and cons of the different methods available for raising capital: returning to the original financial partners (VC and PE backers), finding a strategic partner, or launching an IPO in the United States or Australia? Was there some other alternative?

EXHIBIT 2: COMPARISON OF MONTHLY FEES (IN US$) Financial Institution ChimpChange Bank of America (Core chequing account) Wells Fargo (Everyday chequing account) Monthly Fee 0 12 10 25 Chase (Premier Plus account) 10 Citibank (Basic chequing account) 15 HSBC (Choice chequing account) Note: Some fees might be waived if the customer had more than a certain minimum amount (usually US$1,500) in the account every day over the month. Source: Created by the case author using data from ChimpChange Limited, Prospectus: ChimpChange Limited-ABN 34 150 762 351, 2017, 24, accessed August 31, 2018, www.chimpchange.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/prospectus.pdf. EXHIBIT 3: POTENTIAL FUTURE OF THE FACE OF BANKING IN THE FUTURE Lend g with out De sits Tra ng without Tra ers Service Intermediati on with Branches Service wout Bance Bank Sheets Inv sting wit out Managers Mergers ond Potential Future Scenarios Acquistions Experie out without Advisors Security Doredom Privacy Operations W out Infrast. cture Payments wi out Midemen Chce wi out Fands Source: Created by the case author using data from "Figure 1: A Thought Exercise: Reimagining the Future of Banking," in Deloitte Center for Financial Services, Banking Reimagined: How Disruptive Forces Will Radically Transform the Industry in the Decade Ahead, 5, 2016, accessed August 8, 2018, www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/financial- services/us-fsi-banking-industry-outlook-2016.pdf.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts