Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Referring to the article Factors affecting trust in Market Research Relationships, identify the factors affecting trust? How many constructs have been used to measure the

- Referring to the article Factors affecting trust in Market Research Relationships, identify the factors affecting trust?

- How many constructs have been used to measure the perceived researcher interpersonal characteristics? Cite them.

- How many variables (items) have been used to measure each of the above constructs? What is the measurement scale related to these items?

- How many hypotheses have been stated by the authors?

- What are the hypotheses stated by the authors concerning the impact of perceived researcher interpersonal characteristics on user trust in the researcher?

- What is the statistical method used to validate the theoretical framework suggested by the authors (Figure 1 page 83)?

- Was hypothesis 2 supported? Why? State the conclusion related to the testing of this hypothesis?

- Was hypothesis 3 supported? Why?

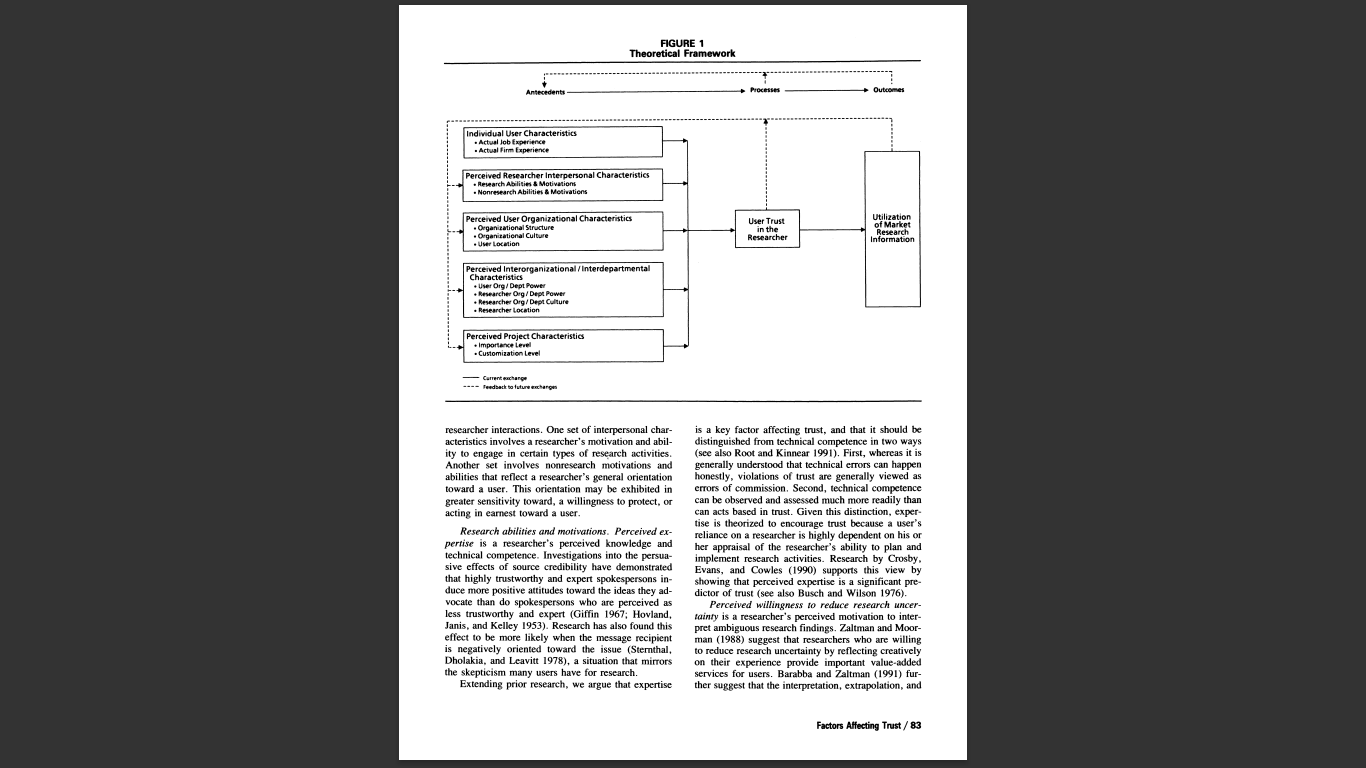

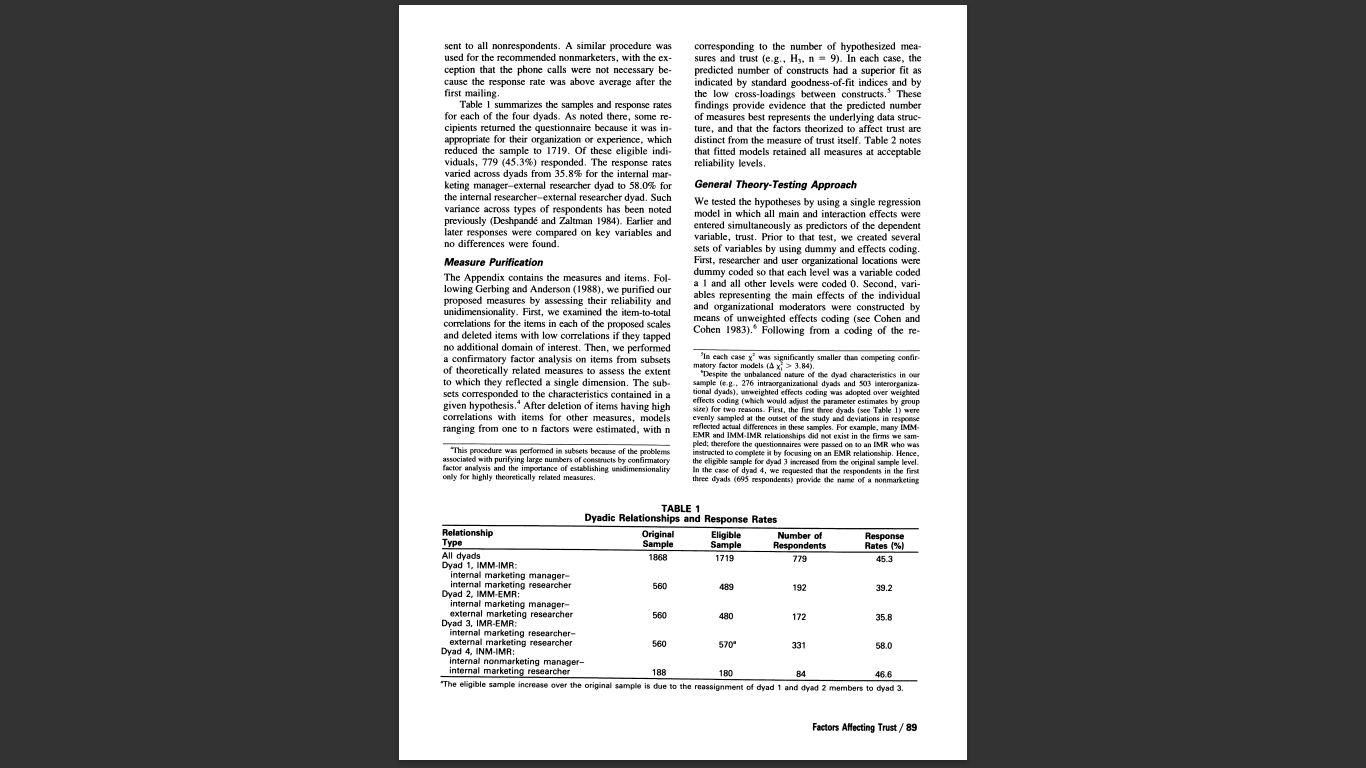

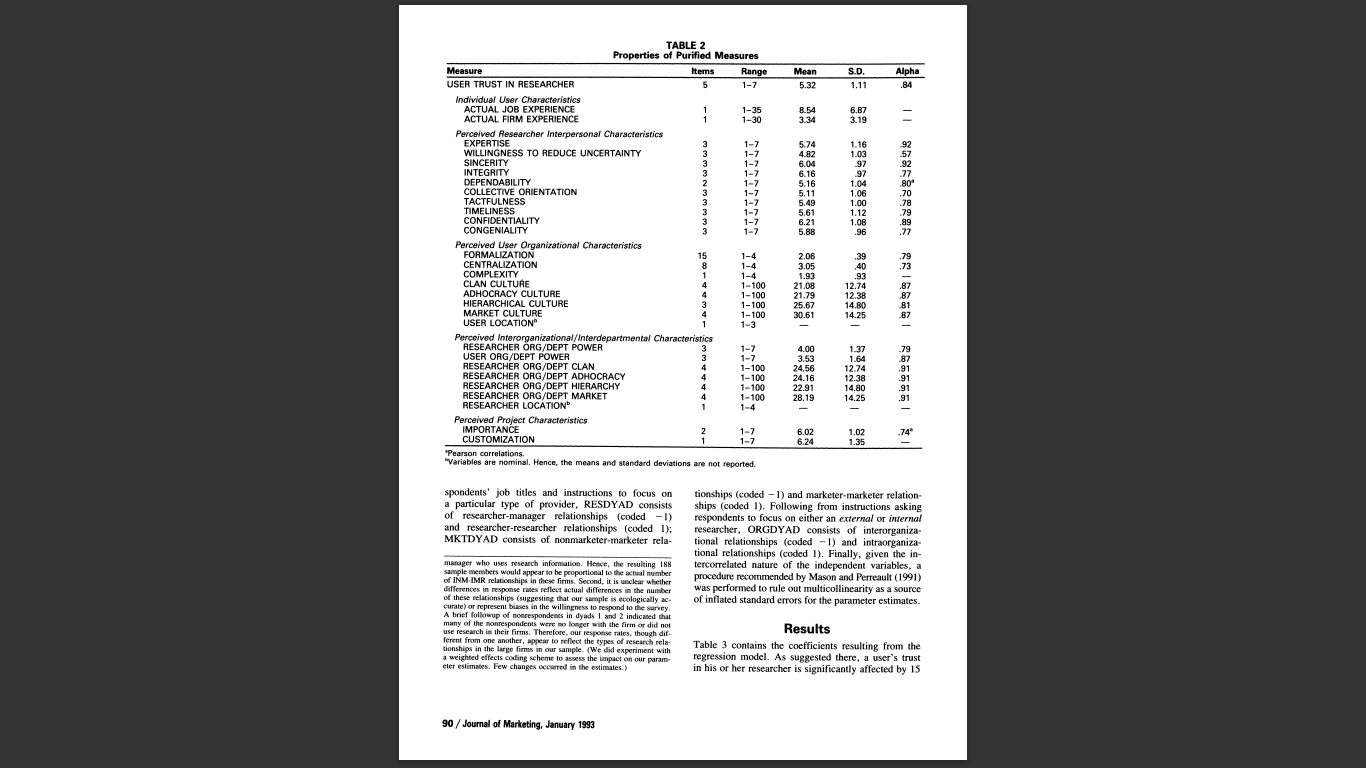

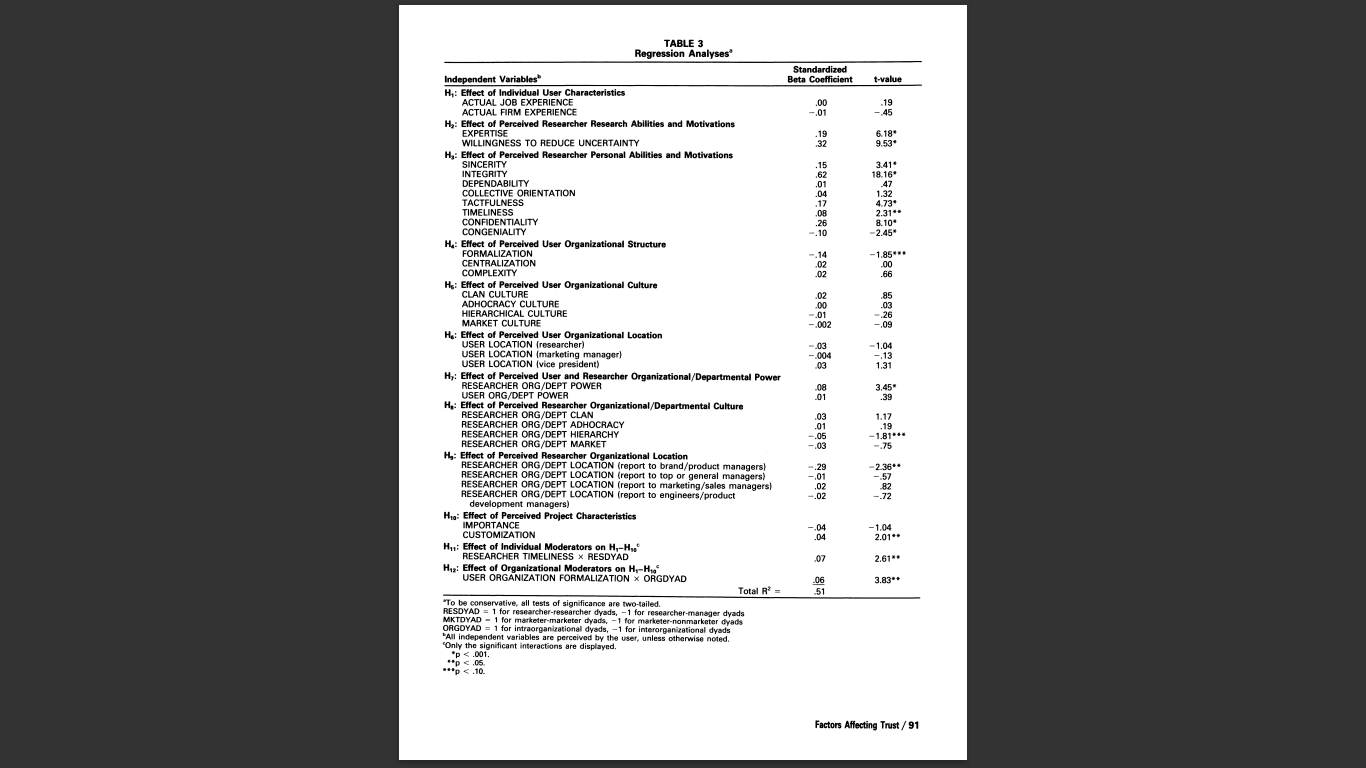

Eactors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relatlonships Building on previous work suggesting that trust is critical in facilitating exchange relationships, the authors describe a comprehensive theory of trust in market research relationships. This theory focuses on the factors that determine users' trust in their researchers, including individual, interpersonal, organizational, interorganizational/interdepartmental, and project factors. The theory is tested in a sample of 779 users. Results indicate that the interpersonal factors are the most predictive of trust. Among these factors, perceived researcher integrity, willingness to reduce research uncertainty, confidentiality, expertise, tactfulness, sincerity, congeniality, and timeliness are most strongly associated with trust. Among the remaining factors, the formalization of the user's organization, the culture of the researcher's department or organization, the research organization's or department's power, and the extent to which the research is customized also affect trust. These findings generally do not change across different types of dyadic relationships. - HE use of information has been identified as a source of a firm's market orientation (Kohli and Jaworski 1990) and sustainable competitive advantage (Day 1991; Glazer 1991; Porter and Millar 1985). One factor that distinguishes firms that merely possess information from those that use information is the level of trust users have in producers of information. Trust has been found to influence the perceived quality of user-researcher interactions, the level of researcher involvement, the level of user commitment to the relationship, and the level of market research' utiliza- Christine Moormen is Assistant Prodessor of Marketing, Graduate School of Business, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Rahit Destpande is Professor of Marketing, Amos Tuck School of Business Administration, Dartmouth College. Gerald Zaltman is Joseph C. Wilson Professar of Marketing, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University. The first author thaniks the Graduase School, University of Wisconsin-Madisan, the second author thanks the Tuck Associates Program, and all three authors thank the Marketing Scienos Instituse for supporting the research, as well as Jon Austin, Bob Owyer, Ajay Kohli, and Robert Spekman for their comments on a previous version of the manuscript, and Jill Onum for her assistance in data collection and manuscript preparation. "We use the Iem "market" research mather than "marketing" re. search throughout to refer to che infermation that is collected rather than the fursctioful area or department. Hence, our focus is on marker tion (Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpande 1992). Trust is important to research relationships because, among other things, users must frequently rely on market research to design and evaluate marketing strategies, though they are often unable to evaluate research quality. Hence, being able to trust researchers to ensure quality and to interpret implications correctly for the firm is critical to the user's reliance on research in decision making. Despite the importance of trust, scholarly inquiry on the topic has been hampered in two ways. First, very little academic research has attempted to document empirically the factors that affect trust in marketing relationships (cf. Anderson and Weitz 1990; Dwyer and Oh 1987). In fact, no study has attempted to develop a theoretical framework of factors that influence trust in research relationships. Second, research has not systematically distinguished trust from related factors. For example, Sullivan and Peterson (1982) assess trust by measuring sincerity, caution, effort in establishing a relationship, equality, goal congruence, consistency, and expectations of cooperation. Crosby, Evans, and Cowles (1990) assess trust research informarion though we eansider selationships berwen various users and markering researchers. by measuring sincerity, competitive behaviors, honesty, and beliefs about information sharing. As we argue, some of these dimensions are viewed more appropriately as factors that influence trust than as components of trust itself. This article develops a theory about factors affecting user trust in marketing researchers. After describing our conceptualization of trust, we present this theory and formal hypotheses. We then report the results of an empirical study designed to test the hypotheses. Finally, we discuss the implications and limitations of our study and offer suggestions for future research. Trust Trust is defined as a a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence (Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpand 1992). This definition spans the two general approaches to trust in the literature (see also Dwyer and Lagace 1986), First, considerable research in marketing views trust as a belief, confidence, or expectation about an exchange partner's trustworthiness that results from the partner's expertise, reliability, or intentionality (Anderson and Weitz 1990; Blau 1964; Dwyer and Oh 1987; Pruitt 1981; Rotter 1967; Schurr and Ozanne 1985). Second, trust has been viewed as a behavioral intention or behavior that reflects a reliance on a partner and involves vulnerability and uncertainty on the part of the trustor (Coleman 1990; Deutsch 1962; Giffin 1967; Schlenker, Helm, and Tedeschi 1973; Zand 1972). This view suggests that, without vulnerabiliry, trust is unnecessary because outcomes are inconsequential for the trustor. It is consistent with Deutsch's (1962) definition of trust as "actions that increase one's vulnerability to another," which Coleman (1990, p. 100) suggests might include "voluntarily placing resources at the disposal of another or transferring control over resources to another." This view also suggests that uncertainfy is critical to trust, because trust is unnecessary if the trustor can control an exchange partner's actions or has complete knowledge about those actions (Coleman 1990; Deutsch 1958), We argue that both belief and behavioral intention components must be present for trust to exist. Accordingly, a person who believes that a partner is trustworthy and yet is unwilling to rely on that partner has only limited trust. Further, reliance on a partner without a concomitant belief about that partner's trustworthiness may indicate power and control more than it does trust. In the context of market research relationships, vulnerability and uncertainty arise for several reasons. Many users, for example, are unable to evaluate the quality of research services, which means that they must rely on researchers to give "credence" to or ensure a level of information quality. Other users are unable to interpret research findings and assess their implications, which means they must rely on researchers to perform such interpretive functions. Furthermore, users who rely on researchers for scanning and information collection are vulnerable because their knowledge of the environment depends, to a large extent, on their researchers' efficacy. Also increasing the extent to which users are vulnerable to researchers is the fact that researchers often provide information that is used to evaluate users' decisions (Perkins and Rao 1990; Zaltman and Moorman 1989). Finally, in relationships between users and researchers in an external research organization, users must share proprietary information about future marketing strategies, placing themselves at the mercy of researchers' prudence in maintaining confidentiality. Theoretical Relationships A model of the antecedents and consequences of users' trust in marketing researchers is illustrated in Figure 1. A variety of factors that affect trust are shown, including individual, interpersonal, organizational, interdepartmental/interorganizational, and project factors. Trust, in turn, influences a number of relationship processes (only trust is shown), which affect the extent to which market research is used. Trust and research utilization can, in turn, feed back to affect users' perceptions of researchers' characteristics. We do not formally investigate this feedback effect. Instead, our focus is on the factors affecting trust. The Role of Main-Effect Characteristics in Trust: Individual User Characteristics Two related characteristics, user job experience and user firm experience, are investigated for their influence on user trust in researchers. Experience refers to the user's tenure in the job or with the firm. Users with lower levels of experience are expected to be more willing to trust researchers because of their lack of company, marketing, or research knowledge. Experienced users, in contrast, are likely to have more knowledge and confidence in their own ability to use research and to manage relationships (McDaniel, Schmidt, and Hunter 1988). These qualities make experienced users less likely to rely on researchers in relationships. Hence: H1 : User trust in researchers is higher when user (a) job experience of (b) firm experience is lower. Researcher Interpersonal Characteristics Interpersonal characteristics refer to a broad set of researcher qualities that are demonstrated in user- 82 / Journal of Marketing, January 1993 researcher interactions. One set of interpersonal characteristics involves a researcher's motivation and ability to engage in certain types of research activities. Another set involves nonresearch motivations and abilities that reflect a researcher's general orientation toward a user. This orientation may be exhibited in greater sensitivity toward, a willingness to protect, or acting in earnest toward a user. Research abilities and motivations. Perceived expertise is a researcher's perceived knowledge and technical competence. Investigations into the persuasive effects of source credibility have demonstrated that highly trustworthy and expert spokespersons induce more positive attitudes toward the ideas they advocate than do spokespersons who are perceived as less trustworthy and expert (Giffin 1967; Hovland, Janis, and Kelley 1953). Research has also found this effect to be more likely when the message recipient is negatively oriented toward the issue (Stemthal, Dholakia, and Leavitt 1978), a situation that mirrors the skepticism many users have for research. Extending prior research, we argue that expertise is a key factor affecting trust, and that it should be distinguished from technical competence in two ways (see also Root and Kinnear 1991). First, whereas it is generally understood that technical errors can happen honestly, violations of trust are generally viewed as errors of commission. Second, technical competence can be observed and assessed much more readily than can acts based in trust. Given this distinction, expertise is theorized to encourage trust because a user's reliance on a researcher is highly dependent on his or her appraisal of the researcher's ability to plan and implement research activities. Research by Crosby, Evans, and Cowles (1990) supports this view by showing that perceived expertise is a significant predictor of trust (see also Busch and Wilson 1976). Perceived willingness to reduce research uncertainfy is a researcher's perceived motivation to interpret ambiguous research findings. Zaltman and Moorman (1988) suggest that researchers who are willing to reduce research uncertainty by reflecting creatively on their experience provide important value-added services for users. Barabba and Zaltman (1991) further suggest that the interpretation, extrapolation, and creation of meaning from research data constitute the primary value-adding function that research performs. Furthermore, Blattberg and Hoch's (1990) findings that individuals who use both marketing models and intuition make better marketing decisions than do individuals who use models or intuition support the importance of judgment in the interpretation of research findings. These findings and suggestions follow from the fact that research studies rarely provide all of the information needed for important decisions and that every research approach has limitations, particularly in terms of how the data can be analyzed and interpreted. Therefore, because research often creates uncertainty that users must reduce in order to make decisions, users trust researchers who display a willingness to assist in this process. This discussion suggests: H2 i User trust in researehers is higher when researcher (a) expertise or (b) willingness to reduce uncertainty is perceived to be higher rather than lover. Nonresearch abilities and motivations. Perceived sincerify is the extent to which a researcher is perceived to be honest and to be someone who makes promises with the intention of fulfilling them (Larzeleve and Huston 1980). Research suggests that when a source's past communications are truthful, receivers are more likely to rely on current communications from that source (Gahagan and Tedeschi 1968; Schlenker, Helm, and Tedeschi 1973). As Schlenker and his coauthors state, "A promiser who did not back up his words with corresponding deeds soon would be distrusted (p. 420) ). Other research has suggested that sincerity is a subdimension of trust (see Crosby, Evans, and Cowles 1990; Kaplan 1973; Rotter 1967). Consistent with the first view, we believe that sincerity is better described as a determinant of trust, because when users sense that researchers are sincere or "truth tellers (Zaltman and Moorman 1988), they extend trust because doing so lessens the vulnerability and uncertainty associated with research relationships. Perceived integrity is a researcher's perceived unwillingness to sacrifice ethical standards to achieve individual or organizational objectives. Past research has demonstrated an empirical linkage between integrity and trust. For example, Butler and Cantrell (1984) report that integrity is a significant determinant of subordinate trust in superiors. In the context of research relationships, Hunt, Chonko, and Wilcox (1984, p. 312) suggest that threats to integrity standards all have "the common theme of deliberate production of dishonest or less-than-completely-honest research," involving falsifying figures, altering research results, misusing statistics, or misinterpreting the results of a research project to support a predetermined personal or corporate point of view. Consequently, researchers who demonstrate integrity are likely to be trusted be- cause users can expect them to adhere to higher standards and thereby remain more objective throughout the research process. Percenved dependability is a researcher's perceived predictability (Rempel and Holmes 1986). Other researchers have distinguished between predictability and dependability, claiming that an individual's actions are regarded as "predictable" whereas an individual is regarded as "dependable" (Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna 1985). Used in the latter way, dependability has some basis in other interpersonal antecedents, such as sincerity and integrity (see Johnson-George and Swap 1982 for a similar distinction). However, dependability that is based in a sense of predictability (as used in our research) is distinct from these higher order interpersonal qualities. Trust increases with dependability as users come to rely on the predictability and consistency of researcher actions. High variance behavior, in contrast, reduces trust. Perceived collective orientation is a researcher's perceived willingness to cooperate with users (Zaltman and Moorman 1988). Research has found that individuals are more willing to commit to another party if that party is believed to be cooperative as opposed to competitive or individualistically oriented (Anderson and Weitz 1990; Pruitt 1981). Macneil (1980) refers to this orientation as a flexibility that partners allow one another in relationships. Given this orientation, we expect trust to follow. Perceived tactfulness is the level of etiquette a researcher displays during exchanges with users. Tact is especially important in communicating research findings that do not meet users' expectations or that could be embarrassing, because users strongly prefer research that supports the status quo or confirms prior beliefs (Deshpand and Zaltman 1982, 1984; Perkins and Rao 1990; Root and Kinnear 1991). If users cannot count on researchers to have a sense of etiquette when they discover bad news, researchers will not be trusted. Perceived timeliness is a researcher's perceived efficiency in responding to user needs. Relatedly, Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry (1990) describe responsiveness as a factor that affects consumers' perceptions of service quality. Austin (1991) also notes the importance of timeliness to user satisfaction with and trust in researchers and suggests that it involves paying bills on time, sending requested information or materials in a timely manner, and providing feedback within a reasonable time period. Finally, timeliness has been reported to be correlated positively with manager satisfaction and the utilization of information systems (Bailey and Pearson 1983). Perceived confidentiality is the researcher's perceived willingness to keep proprietary research findings safe from the user's competitors. Other research has demonstrated the importance of confidentiality to trust and related exchange processes (Bailey and Pearson 1983; Hunt, Chonko, and Wilcox 1984; Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry 1990). For example, the perceived confidentiality of disclosures increases users" perceptions of counselors' credibility (Corcoran 1988), increases the willingness to relate in social support group settings (Posey 1988), and is a critical component of social exchange and trust among community members (Aguilar 1984). Perceived congeniality is the extent to which a researcher is perceived to be friendly, courteous, and positively disposed toward the user. This dimension has also been linked to satisfaction (Ives, Olson, and Baroudi 1983) and perceptions of service quality (Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry 1990). Though congeniality may not always be necessary to establish good working relationships (Crouch and Yetton 1988), it seems reasonable that, given the intangible nature of research exchanges, users would be likely to make attributions about researchers' trustworthiness on the basis of a variety of cues. One simple cue, which reflects a minimal level of user orientation, is a researcher's courtesy to the user. Being courteous, of course, is not expected to be sufficient to maintain trust without other researcher qualities; however, congeniality should contribute to trust. Given that the aforementioned qualities reduce risk and uncertainty, researchers displaying attitudes and behaviors that reflect these abilities and motivations should be able to increase users' beliefs in their trustworthiness and increase users' willingness to rely on them. Hence, we formally hypothesize: H3 : User trust in researchers is higher when researcher (a) sincerity, (b) integrity, (c) dependability, (d) collective orientation, (c) tactfulness, (f) timeliness, (g) confidentiality, or (h) congenizlity is perceived to be higher rather than lower. User Organizational Characteristics User's organizational structure. Two aspects of firm structure, bureaucratization and complexity, are related to trust. Perceived organizational bureaucratization is the degree to which a user views his or her organization as managed primarily through formalized relationships and a centralized authority (John 1984). Formalization is the degree to which rules define organizational roles, authority relations, communications, norms and sanctions, and procedures (Hall, Haas, and Johnson 1967; John and Martin 1984), including the flexibility managers have when handling a particular task (Deshpand 1982). Centralization is the degree of delegation in organizational decision-making authority (Aiken and Hage 1968). There are two general views of the effect of bu- reaucracy on trust. One view suggests that bureaucratically arranged organizations produce trust through structural and procedural controls, especially when other person-based and process-based modes are absent (Shapiro 1987; Zucker 1986). The other view is that bureaucratic structures established to ensure efficiency (Arrow 1974) reduce the likelihood of trust in organizational relationships. This view is supported by research noting that bureaucratic structuring increases opportunism (John 1984) and that managers deprived of decision-making authority have correspondingly less trust in their organizations (Hrebiniak 1974). Given that we view trust as developing from interpersonal relationships, organizational bureaucratization is expected to reduce trust because it discourages interpersonal risk-taking, including displays of uncertainty and vulnerability (Fox 1974). A bureaucratic environment also discourages flexibility toward exchange partners, thus reducing trust (John and Martin 1984). As Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh (1987, p. 349) note, -...reliance on bureaucratic structuring will affect trustworthiness adversely in that unilateral decisions, centralized authority, and operations "strictly by the book" do not communicate desired coordination, reciprocity, or commitment to the relationship." Perceived organizational complexity is the degree of formal structural differentiation within an organization (Blau and Schoenherr 1971). Price and Mueller (1986) note that highly complex organizations are characterized by many occupational roles, divisions, departments, levels of authority, and operating sites. Complexity can be found in the horizontal differentiation of divisions and departments, the vertical differentiation of levels of authority, and the spatial differentiation of operating sites. Complexity should reduce trust in research relationships for two reasons. First, greater complexity may mean that researchers and users are not physically close to one another, which interferes with their ability to build trust in relationships. Additionally, complexity may threaten trustbuilding because of the likelihood of greater dissimilarities in beliefs and norms as firms add more divisions, departments, and roles. Hence, we hypothesize: H4 : User trust in researchers is higher when the user organization's (a) formalization, (b) centralization, or (c) complexity is percelved to be lower rather than higher. User's percelved organizational culture. Organizational culture, defined as "the pattern of shared values and beliefs that help individuals understand organizational functioning and that provide norms for behavior in the organization" (Deshpande and Webster 1989,p,4), is theorized to affect trust according to the type of culture present. Deshpand, Farley, and Webster (1992) assess four modal types of organizational cultures: clans, adhocracies, hierarchies, and markets. Clans emphasize cohesiveness, participation, and teamwork. Members of organizations with strong clan cultures should be willing to trust their researchers because the cultural norm is the establishment and maintenance of successful working relationships (Ouchi 1980). Moreover, clan members are generally viewed as part of an extended family, a situation ideal for the creation and maintenance of trusting relationships. Adhocracies emphasize entrepreneurship, creativity, and adaptability. Hence, members of organizations with strong adhocracies should be willing to trust researchers because the norms emphasize tolerance and flexibility (Mintzberg 1979) and because such cultures are likely to place a premium on employee skills (including research skills) that offer stability in dynamic settings. Hierarchies emphasize order, uniformity, and efficiency. Lower levels of trust are expected because such cultures provide sufficient stability and control to make trust less necessary or salient. Markets emphasize competitiveness and goal achievement. Trust is expected to be lower in these cultures because personal relationships (i.e., team membership) are viewed as instrumental and are used opportunistically (Williamson 1975). We hypothesize: H5 : User trust in researchers is higher when the user organization is perceived to be a (a) stronger rather than weaker, clan or adhocracy cultare of (b) weaker rather than stronger, hierarchical or market calrure. User organizational location. Research indicates that a manager's position within an organization affects a variety of interpersonal and decision-making processes. For example, organizational position has been reported to influence a manager's knowledge about organizational phenomena (Walker 1985), self-esteem (Tharenou and Harker 1982), leadership style (Adams 1977), and perceived faimess (Stolte 1983). More prominent organizational positions also have been shown to be related to trust by lower status employees (Tjosvold 1977) and general trust in the organization, including the degree to which it is perceived as benign, cooperative, or consistent (Hrebiniak 1974). Conversely, other research has shown no linkage between organizational location and trust (Zalesny, Farace, and Kurcher-Hawkins 1985). Given the view of trust in this research-as involving a willingness to rely on another party-a theoretical position that departs from the literature is offered. We argue that users with lower levels of authority, in general, are less able to influence the behaviors of others in the firm. Hence, they develop more trusting relationships to accomplish goals. Users in higher level positions, in contrast, may be able to accomplish their goals without trusting relationships. We hypothesize: H6. User trust in researchers is higher when users hold organizational positions with lower rather than higher levels of authority. Interorganizational/Interdepartmental Characteristics When a relationship involves an internal user and an external researcher, the relationship is interorganizational, whereas if the relationship involves an internal user and an intemal researcher, the relationship is interdepartmental. Three general categories comprise this set of characteristics. One set involves users' perceptions of power in organizational or departmental relationships; the other two involve users' perceptions of two research organizational or departmental characteristics. Perceived power in the relationship. User deparmental/organizational power generally is due to the user's status as research initiator and buyer whereas researcher organizational/deparmental power is most likely to emanate from the researcher's specialized experiential, informational, or technological assets. Previous research on power in relationships has led to two general findings. First, power breeds trust (Frost, Stimpson, and Maughan 1978; Sullivan and Peterson 1982), functional conflict (from the perspective of the firm having power, Anderson and Narus 1990), and respect from exchange partners (Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz 1987). Second, power creates conflict (from the perspective of the firm against which the power is used; Anderson and Narus 1990) and mistrust of the powerful parties' intentions (Anderson and Weitz 1990). Following Anderson and Narus (1990), we predict that perceived power will affect trust differently depending on which organization or department has that power. Specifically, given that research organizations or departments have achieved power because of their specialized skills, trust is likely to follow as users rely on those skills in the design and evaluation of marketing strategies. Moreover, when researchers have power due to specialized skills, users may lack the expertise to evaluate research adequately and hence the use of research may involve uncertainty and vulnerability - ideal conditions for trust to emerge (Barber 1983). In contrast, perceived user organization/ department power may be used to direct rescarchers' behaviors, which reduces users' need to trust in the relationship. We formally hypothesize: H7 : User trust in researchers is higher when the perception is that (a) research organizational/departmental power is higher rather than lower or (b) user organicational/ departmental pover is lower rather than higher. User's perceptions of a researcher's culture. Past research has demonstrated that perceptions of an exchange partner's culture affect trust in that partner (see Peterson and Shimada 1978; Sullivan et al. 1981), Hence, we believe that a user's perceptions of a researcher's culture will influence user trust in researchers. As with user cultures, we expect the sense of family in clans and the tolerance and flexibility of adhocracies to be associated with stronger trust in researchers. Conversely, a user will have lower trust in researcher cultures that are hierarchies or markets. Given the presence of different subcultures within a single organization (Deshpand, Farley, and Webster 1992; Deshpande and Webster 1989; Smircich 1983), this effect is expected regardless of whether the unit of analysis is two organizations or two departments. H8 : User trast in researchers is higher when a user perceives a researcher's organizational/departmental culrure to be a stronger clan or adhocracy culture, or to be a weaker hicrarchical or market culture. User's perception of a researcher's location. Researchers located in higher levels of the organization are more likely to influence decision making within the organization than are researchers at lower levels. This capability increases researcher perceived credibility and power which, according to the theory proposed up to this point, increases user trust in them. H3 : User trust in researchers is higher when the researcher's arganizational location is perceived to be higher rather than lower. Project Characteristics Perceived importance of research project. A research project might be important for a variety of reasons. It may, for example, involve a strategic decision (c.g., product addition or deletion), portend important financial or competitive considerations for the firm, or hold important career implications for an individual. Higher project importance levels are expected to increase user trust in researchers because such levels raise users' vulnerability in the relationship, which compels them to work hard at developing effective research relationships and causes increased reliance on researchers. Unimportant projects involve less vulnerability, which means that trust is correspondingly less salient in these relationships. 2 "We acknowledge that users are likely so choose researchers they truat for important projects. However, if we concrod for prior trust in the current exchange, users are alvo likely to trust researchers moee when they are efrgaged in important, as opposed to unimportant, projects, Perceived customization of research project. Heide and Miner (1991) report that customization increases the generation of relationship-specific assets, which other research has linked to increased collaboration in (Williamson 1975), continuation of (Levinthal and Fichman 1988), and positive evaluation of (Surprenant and Solomon 1987) relationships. Like other customized exchanges, custom research entails greater levels of risk for users than does noncustomized research because users must depend on researchers to make relationship-specific decisions and investments throughout the project. This situation produces a more likely context for the development of trust than does a syndicated research project in which less researcher discretion is necessary and, hence, there is less opportunity for user uncertainty and vulnerability. We hypothesize: H30 : User trust in researchers is higher when the project is perceived to be more rather than less (a) important or (b) customized. The Effects of Individual and Organizational Moderators on H1H10 Differences between users and researchers can facilitate or inhibit the role of trust in research relationships. Following Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpande (1992), we theorize about the effects of two individual differences and one organizational difference on the hypothesized relationships. As we consider this part of our research to be exploratory, the hypotheses are more speculative. We do, however, offer formal hypotheses (aside from the null) as a way of furthering research on these moderating effects. Individual differences: members of the same and different communities. Previous work has described community differences between users and providers of knowledge (Caplan, Morrison, and Stambaugh 1975) and how these differences affect knowledge use and other outcomes (Crosby, Evans, and Cowles 1990; Deshpande and Zaltman 1984, 1987). We examine two general types of community differences: (1) when the user and provider are both researchers versus when one is a manager, and (2) when the user and the provider are both in marketing versus when one is a nonmarketer (e.g., an engineer). In general, our theorizing about the effects of similarities and differences is based in the principle of salience in social psychological research. Salience is typically used to refer to stimuli that are prominent in relation to a particular context because of their innate qualities, the situational environment, or a person's prior knowledge or frame of reference. Prior research suggests that individuals tend to pay more attention to, to attribute more causality to, and to be more capable of retrieving salient stimuli (Taylor et al 1979 ; Tversky and Kahneman 1974). Applied to the issue of how dyadic conditions affect the importance of various characteristics to trust, we suggest that characteristics that are shared between dyad members are less salient to the partners and, hence, have a weaker influence on how the relationship operates. In contrast, characteristics that are not shared are more salient to the partners and, hence, have a stronger impact on the relationship. Therefore, users working with researchers from different communities (i.e., manager-researcher and marketer-nonmarketer dyads) are expected to rely more heavily on interpersonal characteristics in the decision to trust because this unshared information will be more salient in the exchange process. These interpersonal characteristics are not expected to be salient when dyads contain members of the same community (i.e., researcher-researcher and marketer-marketer dyads), as both parties are likely to display these characteristics in their exchanges. The effects of the remaining characteristics (e.g, organizational or project factors) on trust are not sensitive to these community differences because they do not vary systematically across similar and dissimilar dyads. Hence, we hypothesize: H11 : The relationships between trust and interpersonal characteristics are stronger for relationships involving dissimilar parties than for relationships inwolving similar parties. Organizational differences: intraorganizational and interorganizational relationships. Given that two departments are more likely to be similar to one another if they are within a single firm than if they are in two different organizations, it follows that organizational characteristics should be more salient, and hence stronger predictors of trust, in interorganizational relationships than in intraorganizational relationships. We expect no differences, however, in the effects of individual, interpersonal, interorganizational/interdepartmental, and project characteristics on trust because such characteristics are not expected to vary systematically in interorganizational and intraorganizational dyads. Hence, we hypothesize: H12 : The relationships between trust and the organiza. tional characteristics are stronger for interorganizational relationships than for intraorganizational relationships. "Though elearly the interorganizational/inerdepartmental characteristics will vary depending of whether the relationship is interoeganizational or intraorganizational, in this case the variability is a function of the mature of the variable and its conceptualization rather than a condition that reflects differences that can be examined empirically, Method Measure Development On the basis of the construct definitions, we either developed measures or borrowed them from past research (see Appendix) and then performed two pretests. The first pretest assisted in item refinement. A list of defined measures and items for those measures was mailed to 10 academicians and 10 practitioners. Following Churchill (1979), we requested recipients to assign each item to the measure they thought appropriate, as well as to note when they thought the item could be represented by more than one measure. The second pretest, which determined that trust could be discriminated adequately from the interpersonal characteristics, involved a sample of 50 randomly selected members of the sample frame. Recipients were asked to evaluate their most recent relationship with either an internal or external researcher. Responses (54%) were analyzed for discriminant validity with related constructs by means of an exploratory factor analysis (principal components analysis with a varimax rotation) and for reliability by examining item-to-total correlations. Results indicated that trust could be differentiated from related constructs and that it was reliable. Procedure A sample of 1680 research users was generated by phoning each firm and division on the Advertising Age 1990 list of the top 200 advertisers. The users consisted of (1) marketing managers (e.g,, vice presidents of marketing, marketing directors, or product and brand managers who evaluated either internal or external researchers), (2) marketing researchers within a firm who evaluated external researchers, and (3) nonmarketing managers (e.g., engineers, product development managers, and manufacturing managers) who evaluated internal researchers. Each sample member was mailed a cover letter, a questionnaire, and a brief author profile. The cover letter explained the purpose of the research and promised a summary of the results to all who returned their business cards with completed questionnaires. The questionnaires, though identical in structure, directed respondents to evaluate different types of relationships. One new dollar bill was affixed to the cover letter as an advance token of appreciation. Finally, respondents were asked for the name and address of one nonmarketing manager who used marketing research. These recommendations yielded 188 eligible respondents, increasing the sample size to 1868 . Three weeks after the first mailing, randomly selected nonrespondents were phoned, reminded of the survey, and encouraged to complete and return the questionnaire. Two weeks after the phoning, a second mailing was sent to all nonrespondents. A similar procedure was used for the recommended nonmarketers, with the exception that the phone calls were not necessary because the response rate was above average after the first mailing. Table 1 summarizes the samples and response rates for each of the four dyads. As noted there, some recipients returned the questionnaire because it was inappropriate for their organization or experience, which reduced the sample to 1719 . Of these eligible individuals, 779(45.3%) responded. The response rates varied across dyads from 35.8% for the internal marketing manager-external researcher dyad to 58.0% for the internal researcher-external researcher dyad. Such variance across types of respondents has been noted previously (Deshpand and Zaltman 1984). Earlier and later responses were compared on key variables and no differences were found. Measure Purification The Appendix contains the measures and items. Following Gerbing and Anderson (1988), we purified our proposed measures by assessing their reliability and unidimensionality. First, we examined the item-to-total correlations for the items in each of the proposed scales and deleted items with low correlations if they tapped no additional domain of interest. Then, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis on items from subsets of theoretically related measures to assess the extent to which they reflected a single dimension. The subsets corresponded to the characteristics contained in a given hypothesis. 4 After deletion of items having high correlations with items for other measures, models ranging from one to n factors were estimated, with n "This procedure was performed in subsets because of the problems associaled with purifying large numbers of construets by confirmatory factoe analysis and the importance of establishing undimensionality only for highly theoretically related measures. corresponding to the number of hypothesized measures and trust (e.g, H3,n=9 ). In each case, the predicted number of constructs had a superior fit as indicated by standard goodness-of-fit indices and by the low cross-loadings between constructs. 5 These findings provide evidence that the predicted number of measures best represents the underlying data structure, and that the factors theorized to affect trust are distinct from the measure of trust itself. Table 2 notes that fitted models retained all measures at acceptable reliability levels. General Theory-Testing Approach We tested the hypotheses by using a single regression model in which all main and interaction effects were entered simultaneously as predictors of the dependent variable, trust. Prior to that test, we created several sets of variables by using dummy and effects coding. First, researcher and user organizational locations were dummy coded so that each level was a variable coded a 1 and all other levels were coded 0 . Second, variables representing the main effects of the individual and organizational moderators were constructed by means of unweighted effects coding (see Cohen and Cohen 1983). Following from a coding of the re- "In each case x2 was significantly smaller than competing confirmatory factor models (x12>3.84). "Despite the unbalanced nature of the dyad characteristies in oer sample (e.g- 276 intraorganizational dyads and 503 imerorganizittional dyads), wrweighted effects coding was adopted over weighoed effects coding (which would adjust the parameter estimates by group size) for two reasons. First, the firs three dyads (sce Table 1) were evenly satipled at the outset of the study and deviations in respoese reflecied actual differences in these samples. For example, many DMMEMR and IMM-IMR relationships did boe exist in the firms we sampled; therefore the questionnaires were passed on to an LMR who was instructed to coemplete in by focusing on an EMR relationship. Hence, the eligible sample for dyad 3 increased from the criginal sample level. In the case of dyad 4 , we requested that the respondents in the first three dyads ( 695 respondenss) provide the name of a nonmarketing Factors Aflecting Trust / 89 "Variables are nominal. Hence, the means and standard deviations are not reported. spondents +job titles and instructions to focus on a particular type of provider, RESDYAD consists of researcher-manager relationships (coded -1 ) and researcher-researcher relationships (coded 1); MKTDYAD consists of nonmarketer-marketer rela- marager who uses research infommation. Heace, the resulting 188 sample mentwers would appear to be proportional to the actual number of INM-IMR relationships in these firms. Second, it is unclear whether differences in response rades reflect actual differences in the number of these telarionships (suggesting that our sample is ecologically accurate) or represent beases in the willingness to respond to the survey. A brief folkrwup of nonrespondencs in dyads 1 and 2 indicated that many of the nonrespondents were no longer with the firm or did not use research in their firms. Therefore, our respoonse raies, though different from one another, mppear to reflect the types of research relationships in the large firms in our sample. (We did experiment with a weighted effects ceding seheme to assess the impact on our parameler estimates. Few changes cecarred in the estimates.) tionships (coded -1 ) and marketer-marketer relationships (coded 1). Following from instructions asking respondents to focus on either an external or internal researcher, ORGDYAD consists of interorganizational relationships (coded -1 ) and intraorganizational relationships (coded 1). Finally, given the intercorrelated nature of the independent variables, a procedure recommended by Mason and Perreault (1991) was performed to rule out multicollinearity as a source of inflated standard errors for the parameter estimates. Results Table 3 contains the coefficients resulting from the regression model. As suggested there, a user's trust in his or her researcher is significantly affected by 15 90 / Journal of Marketing, January 1993 MKTDYAD =1 for marketer-marketer dyads, -1 for marketer-nonmarketer dyads OAGDYAD = 1 for intraorganizational dyads, -1 for interorganizational dyads "All independent variables are perceived by the vser, unless otherwise neted. 'Only the significant interactions are displayed. main and interaction effects. We review these results in the order of the hypotheses. The Effects of Main-Effect Characteristics on Trust As neither of the individual user characteristics is a significant predictor of user trust in the researcher, HLa b is not supported. However, most of the researcher interpersonal characteristics are significant. Both perceived research abilities and motivations significantly predict trust: the researcher's perceived expertise ( =.19,p<.001 and perceived willingness to reduce research uncertainty these findings support h2 many of the nonresearch abilities motivations are also significant predictors trust including researcher sincerity p integrity tactfulness timeliness confidentiality results h3a h3k. congeniality in contrast has a negative effect on failing h3b. finally as dependability collective orientation unrelated h3d not supported. fewer organizational variables have an user trust. organization formalization expected .10 supporting h44. however centralization complexity culture do predict h4b h5 location no which does h6 for interorganizational characteristics we find that power predicts supports h7a. is so h7 perception generally except when hierarchy case partially hsb but fail hsa. researchers who report brand product managers opposed higher levels related negatively providing h9. none other locations significantly project importance h16 customization weak predictor h10 effects individual moderators h1h10 general hypothesized relationships weak. example interactions involving marketing differences indicating lack h11. furthermore only one interpersonal interacts with this interaction indicates timeliness-trust relationship stronger researcher-researcher than researcher-manager relationships. indicate between unaffected by community similarities differences. h12 will be fact there orgdyad examining plotting regression lines under two conditions modcrating variable reveals interesting result. low its dyads intraorganizational dyads. increases result should viewed contingency maineffect noted previously. interact or characteristics. discussion traditional view adopted been based purely psychological approach. our complements extends include sociological theories. hence definition includes both confidence exchange partner component rely reliance turn critical roles vulnerability particular argue if trustor complete knowledge about actions able control transferred resources necessary relationship. given theoretical foundation further establishes distinct from antecedents variety factors may affect level distinguishing concepts accomplishes objectives. first it assists defining nomological network factors. sccond provides preliminary understanding facilitated undermined gives direction future vary concomitantly remainder section discuss provide insight into their managerial implications. more function consistent trend focusing parties personality trait exhibited either party. despite believe would benefit identifying testing levels. orientation-the extent person interested reactive people rubin make likely others. among most important users expect adhere high standards maintain objectivity throughout process. reflected array behaviors over cycle. can at outset clear statement what cannot accomplished time budget constraints. they might even refusal undertake he she feels various constraints preclude collection sound data zaltman end process participate skewed interpretation contributes development maintenance additionally know subject interpretations especially different functional areas. stabilizing come reconciliation competing judgments. suggests several questions. because unable evaluate quality assess degree diminished ability increases. integrity. discovering types cultures structures reward systems foster useful current restructuring internal market departments subcontracting commercial firms. relatedly investigating jointly influence suggest ways manage environments beliefs held themselves others whether opportunistic instrumental thought processes some set beliefs. following next described previously reducing involve using analysis skills skills. such require utilize broad marketplace insights construct explanations findings. shares his her tacit frame reference user. sophisticated participates absorption experienced inventory wagner attempts identify qualities facilitating skill firms attempting recruit individuals. must carefully distinguish strict discussing users. very surprising information used secure competitive advantage. examine cues increase decrease perceptions confidentiality. expressed solely departmental norms procedures contribute detract contracts signed external investigate how absence affects exchanges attention dysfunctional withbolding background undermine utilization deshpande accepted idea expertise highlights affected attri- searcher trusted less managers. designing mind researchers. above-noted exceptions directly suggesting sensitive macro well therefore focus appear account greatest variance another approach potential moderating main structure investigations extend extant literature certain add effectiveness finding differently intra- settings initial step toward end. mixed generate relationship-specific assets past linked cooperation continuity fichman unlike strategic seek understand offset risk associated having handle strategically projects without trusting establish controls monitoring capabilities procedural rules executing compensatory additional insight. considering aggregate see change across stability core apparently valued context salience was expected. theory applicable information-based perhaps generally. difference alluded cause affecting involves search experience credence goods. intangible nature present increasing need provider displays. goods whose assessed direct observation diminish. though relative leaves unanswered question processed during early later encounters partners develop same those stages. longitudinal design could address questions actually develops>

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started