Question

Required: (a) Considering issues of performance measurement and control, what are the benefits and risks of the standardization that you read about in this case?

Required:

(a) Considering issues of performance measurement and control, what are the benefits and risks of the standardization that you read about in this case?

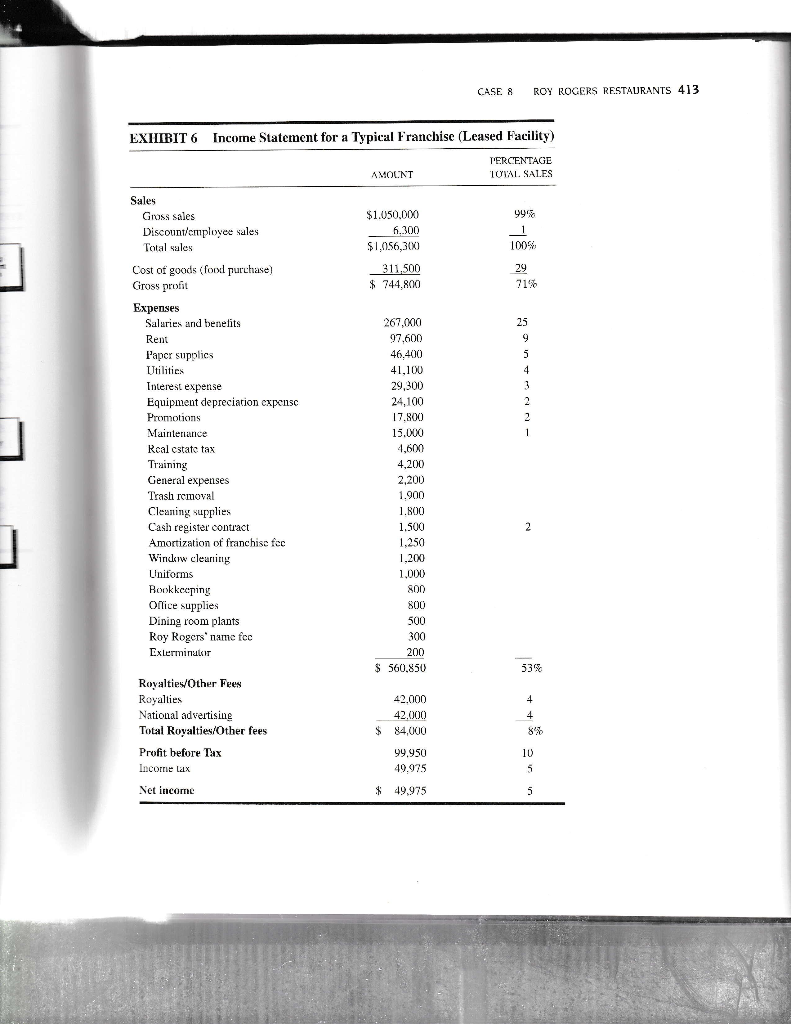

(b) Do Exhibits 5 & 6 point to an attractive opportunity? Give numerical examples where possible. Is there something unusual or misleading when going from Exhibit 5 to Exhibit 6?

(c) Discuss why anyone would want to be a franchisee for this company.

(d) Discuss what Frank Martinez should do about the salad bar issue and consider all angles from a strategic performance measurement and control perspective (i.e., what is best for Roy Rogers; what is best for Jack Towle; what is best for the other franchisees; what if they find out that Jack is getting differential treatment to meet local needs, etc.)

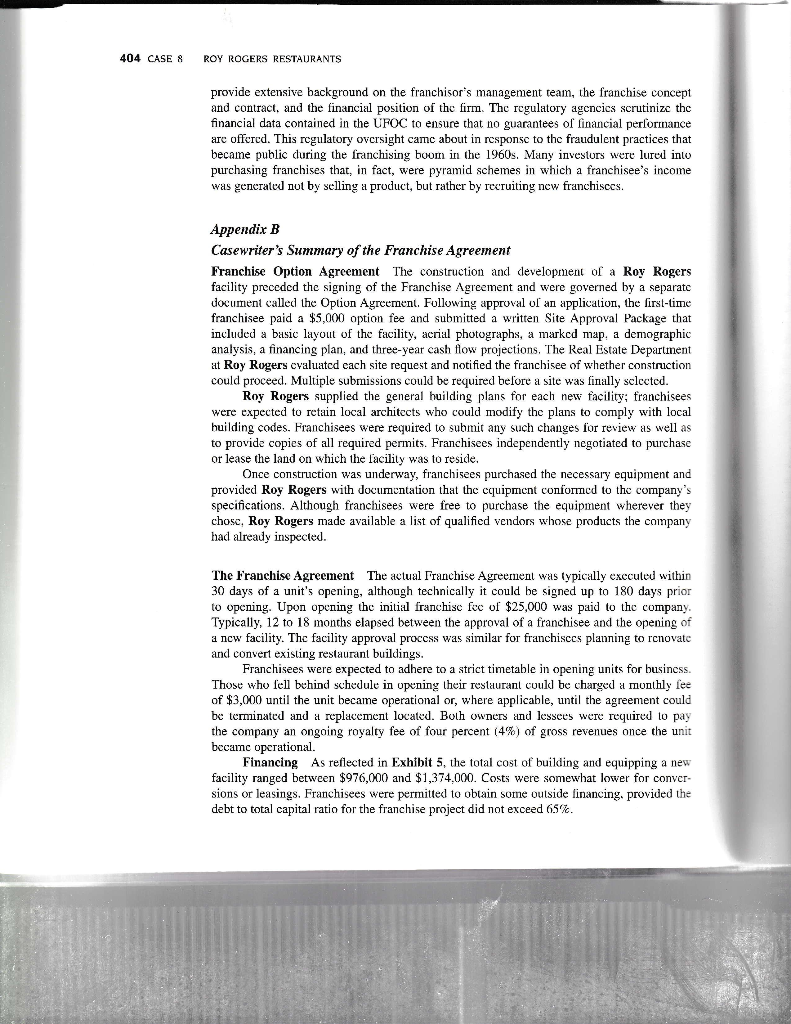

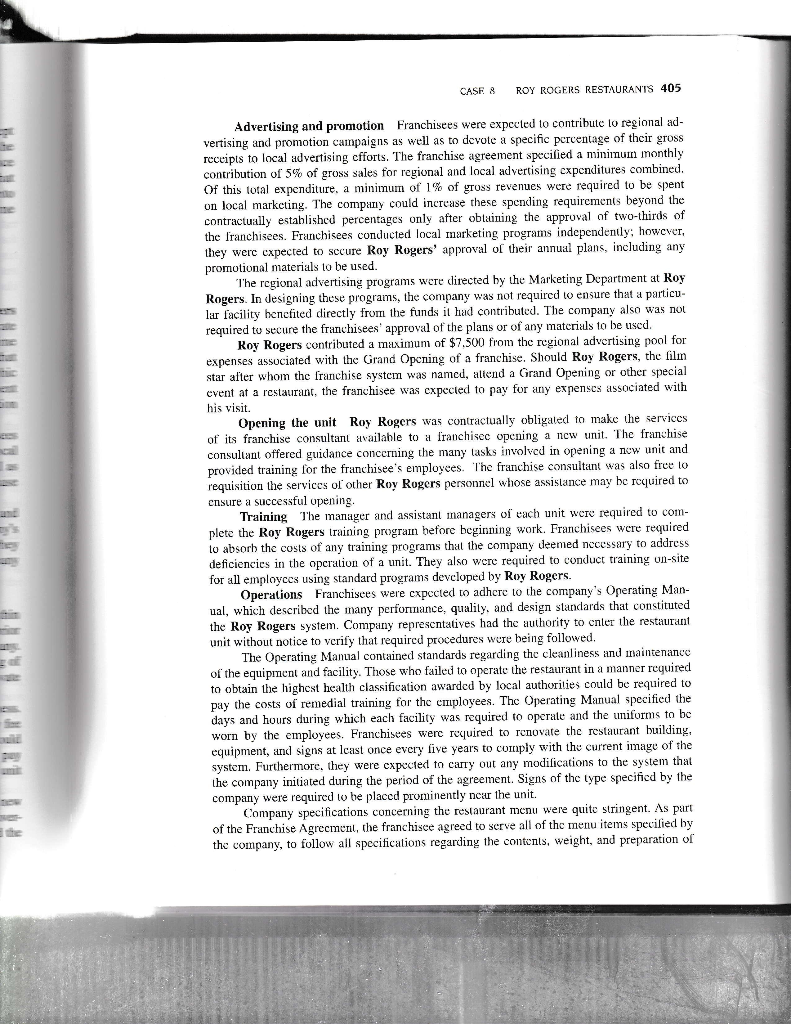

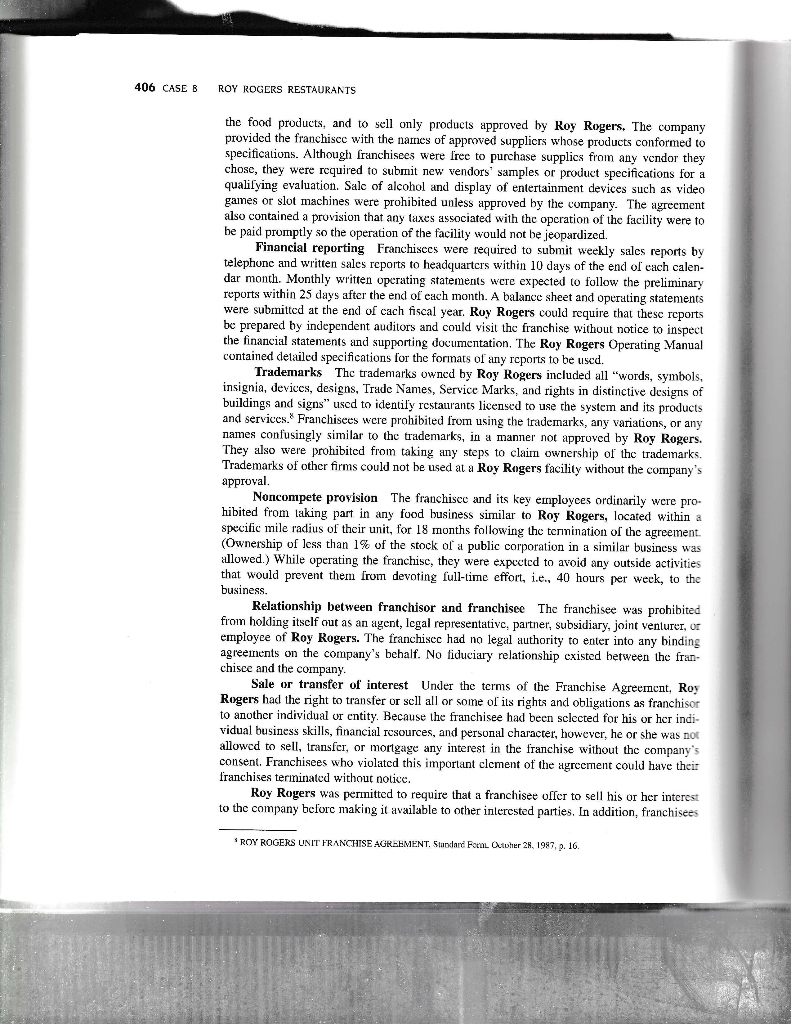

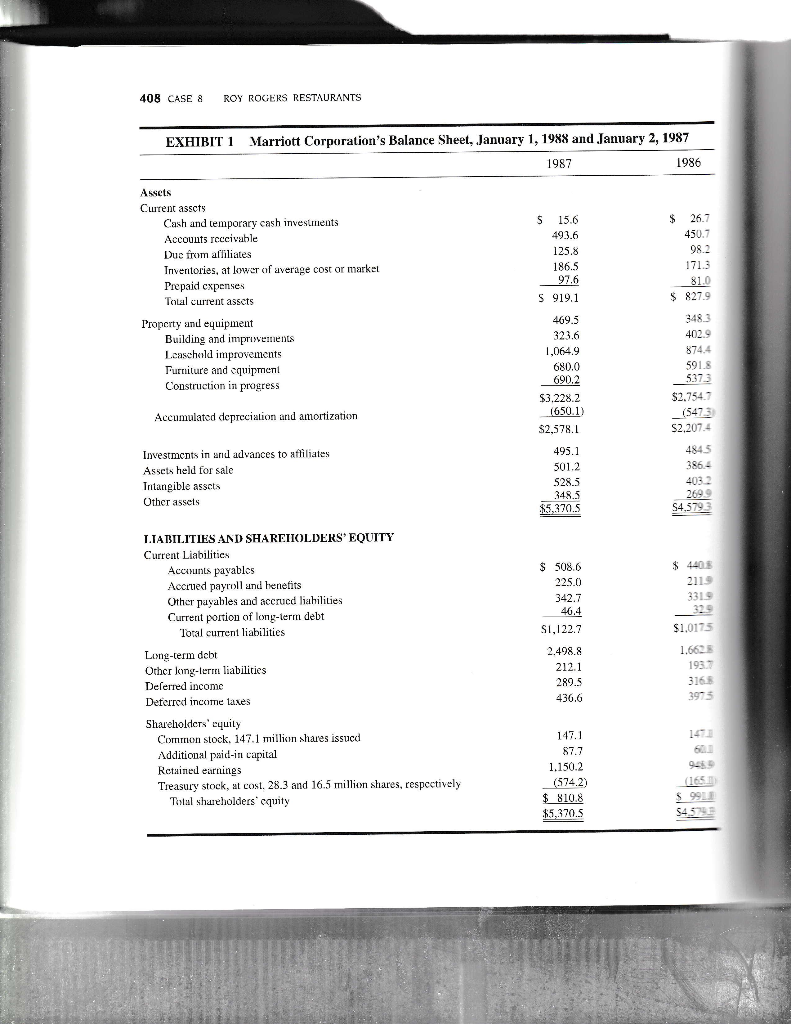

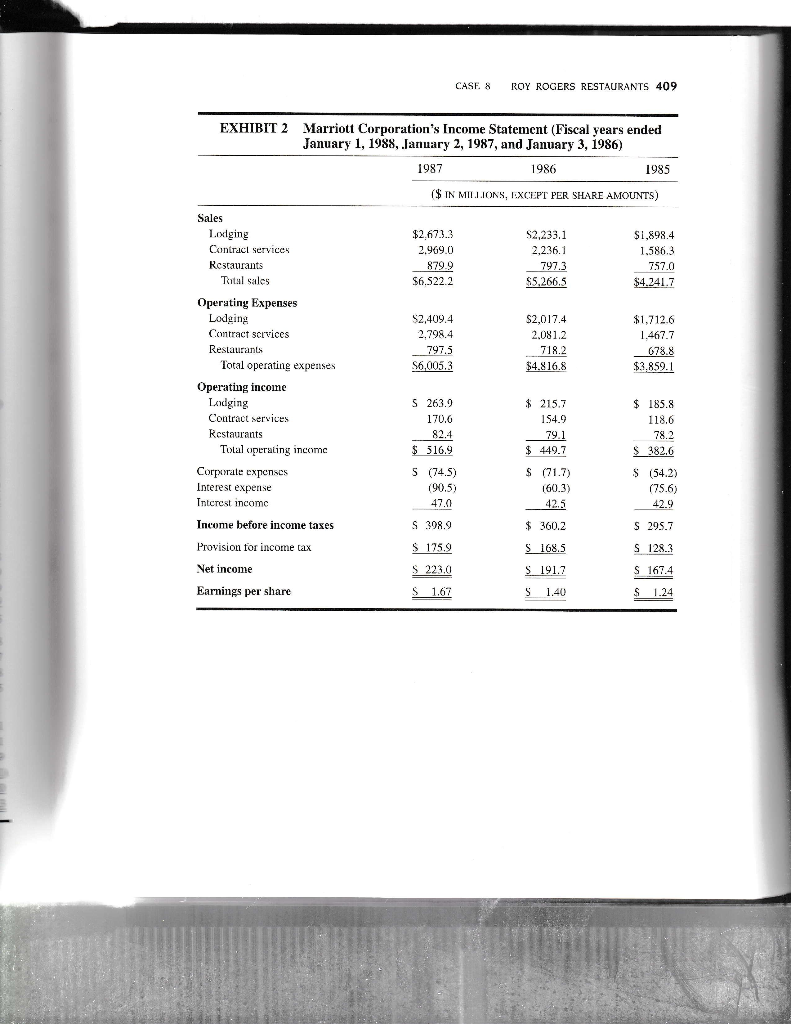

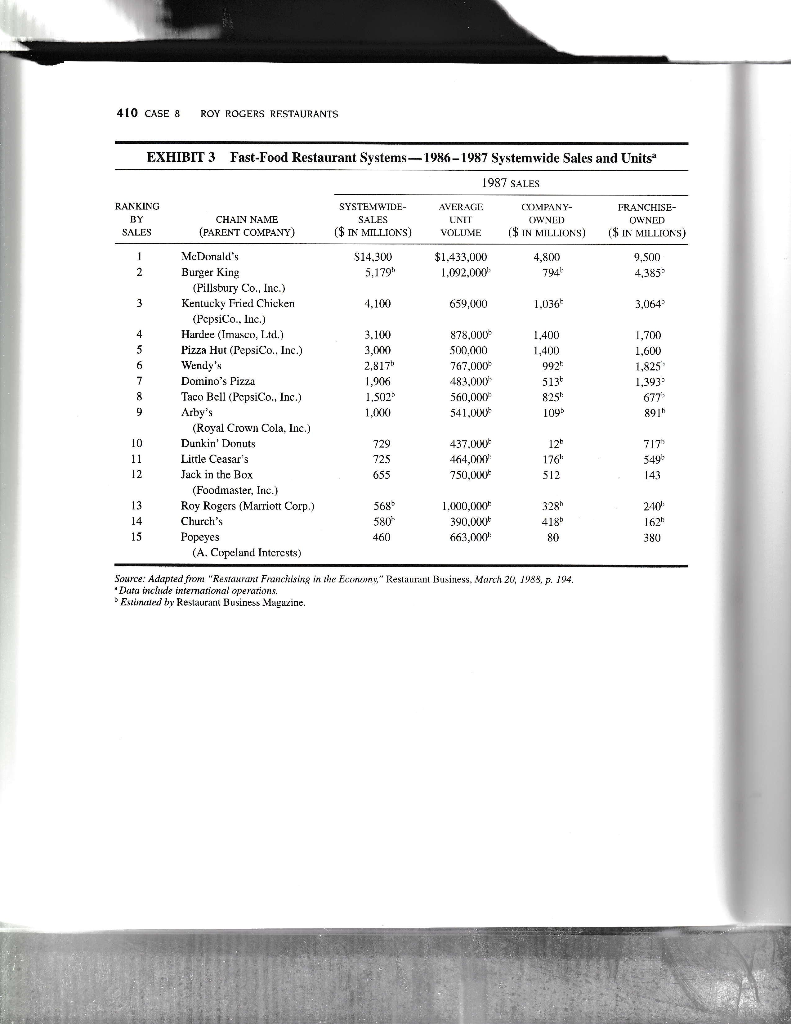

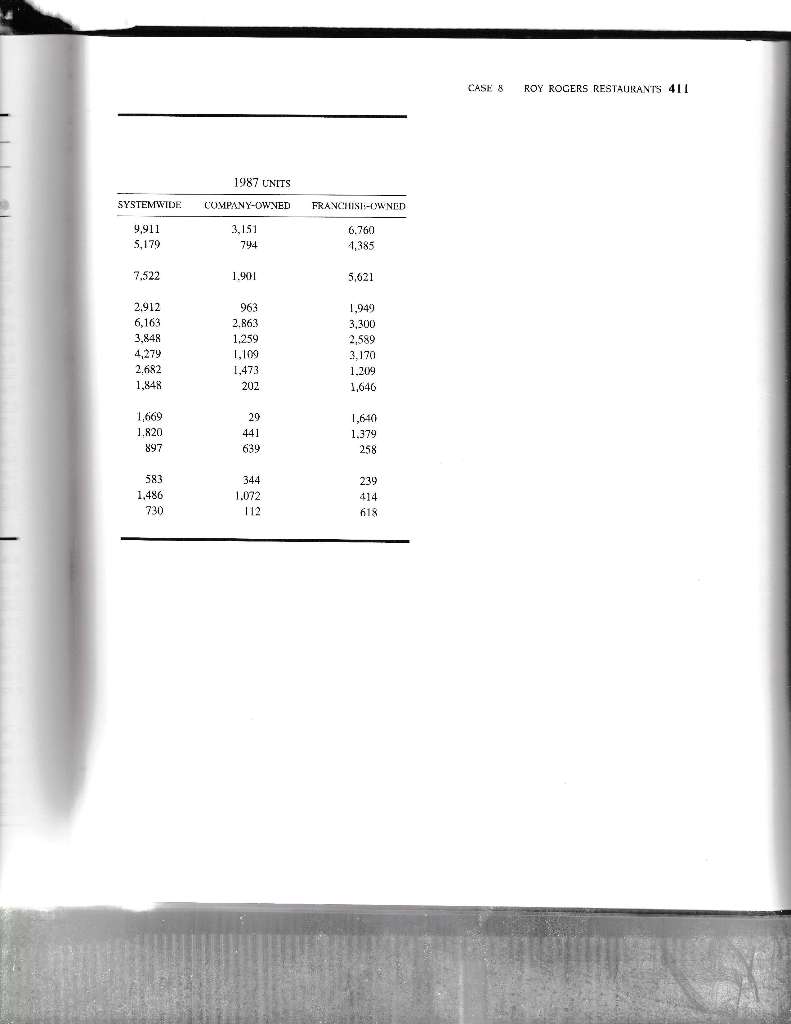

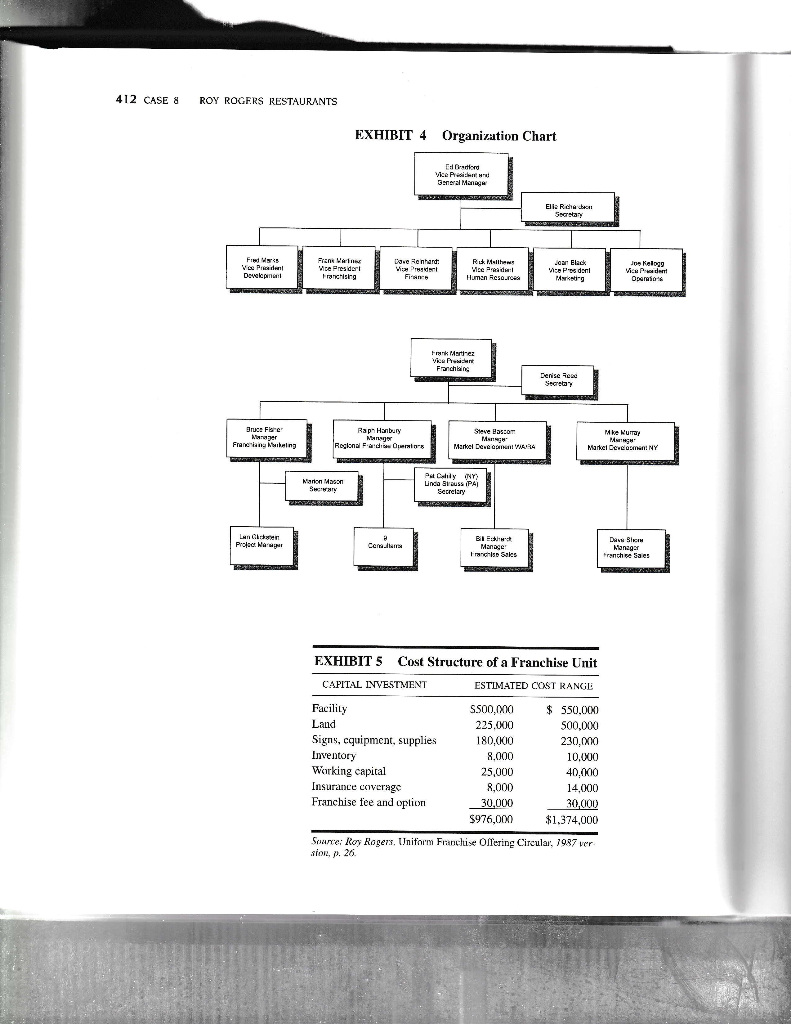

396 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS CASE 8 Roy Rogers Restaurants It was 8:00 p.m. when Frank Martinez, vice president of franchising for Roy Rogers I Restaurants, finally left for home after his second day of meetings in March 1988 with the Franchisee Advisory Council. Although the decision to hold council meetings monthly, rather than biannually, imposed many new demands on himself and his managers, Martinez was encouraged to see a strong rapport developing between the Roy Rogers staff and the franchisees. Attendance at the meetings was increasing, and franchisees were expressing enthusiasm for the company's plans to expand the Roy Rogers system. Martinez was convinced that a successful partnership of Roy Rogers and the franchisees was necessary if the division was to meet the profit growth goal set by Roy Rogers' parent, the Marriott Corporation As he left the office, Frank Martinez, recalled his conversation with Jack Towlc. a major franchisee, who had approached him after the meeting with a request to eliminate the salad-har concept when he built his next Roy Rogers restaurant. Towle, who was Roy Rogers' third-largest franchisee, operated 16 units in major Balti also one of a small number of franchisees who was expected to play a critical role in the company's new growth strategy; he had recently signed a development agreement to build 34 new units hy the end of 1992. As Frank Martinez picked up the phone to inform Ed Brad ford, Roy Rogers' vice president and general manager, of Jack's request, he wondered how the organization should respond to an issue with such major implications for both the com pany and the interests of the 50 other franchisees. Marriott Corporation Roy Rogers Restaurants (often referred to within the company and in advertising as Roy's) was a subsidiary of the Marriott Corporation, a Washington, D.C.-based company which was founded in 1927 by J. Willard Marriott. From its beginnings as a small root beer stand Marriott had grown to $6.5 billion dollars in sales in 1987, with operations and franchises in 50 states and 24 countries. The company was in three principal businesses: lodging, com prised of both hotel operations and lifecare retirement communities, contract food services for businesses, hospitals, educational institutions, and airlines, and restaurants, comprised of family-oriented and fast-food restaurants as well as highway travel plazas. As a corporation Marriott was well-known for its expertise in applying creative financing strategies to real estate development activities. Exhibits 1 and 2 contain the company's 1987 financial statements and provide sales and income data by business sector. In its restaurant segment, Marriott operated or franchised more than 1,100 restaurants in 24 states. Its largest chain, Big Boy, was sold in 1987 to a major franchisee. The appro mately 220 company-owned units operating at the time of the sale were expected to be converted to a new restaurant concept. Roy Rogers, a fast-food chain serving hamburgers fried chicken, and roast beef sandwiches, had both franchises and company-owned facilities Patricia / Miowy MMM W preparadis case under the supervision of Pieser William / Brus, Je us the basis for class disculus recherchustio usine ither incrive or ineffective hundiiny w un administrative and Copyright 19NX by the President and Fellows of Harvard Collnye. Redur plus or mission to lice als onu -800-545-7685 or write larvard Business School Publisbion Boston, MA 172161. Na parlat his publication may here pred sarwina wioval system, used in a specsheel, cred in any form or by my mons-l e , mechanic photocopyice, T wing wherwise without the cubission of Harvnni Rusiness Schnel CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 397 locuted primarily in the Middle Atlantic states, Marriott's Sinallest chain in the restaurant segment was Hot Shoppes, which operated approximately 15 units in the Washington, D.C. area. Marriott also operated a large number of highway restaurants and merchandise outlets azas on 14 turnpikes. The restaurant facilities at the travel plazas included Big Boy and Roy Rogers Restaurants, as well as the fast-food restaurants of competitors such as Burger King. As of 1988, all of these units, including those of the competitors, were operated by Marriott's Travel Plazas Division rather than by the specific chain of which they were a part. The Fast-Food Industry The fast-food industry was comprised largely of restaurant chains, primarily franchises, that served harnburgers, chicken, pizza, sandwiches, or ethnic food such as Mexican or Chinese dishes. Franchising is explained in Appendix A. Chains serving hanburgers as their primary product offering dominated this industry, with approximately 31,511 units and $25.2 billion in sales as of 1986. Fast-food restaurants typically offered restaurant seating or takeout dining, including drive-through service. Takeout service was the most popular, with 60% to 65% of all fast food purchased for takeoul consumption. Fast- food dining had become a habit in American life, with nine out of ten people over the age of 12 eating in a fast-food restaurant regularly. Nevertheless, competition within the fast-food segment of the restaurant market had become fierce as the hamburger market matured, particularly with the entry of untraditional competitors such as supermarkets, convenience stores, and producers of prepackaged products suitable for microwave cooking. Exhibit 3 summarizes information about major competitors in the last-food industry in 1988. One industry analyst identified several factors that distinguish the successful restaurant ventures from the failures. First, the individual restaurant or chain must have a standard of product quality that is acceptable to the consulter. Of equal importance is the restaurant's ability to standardize its concept so that customers can predict what their dining experience will be like well before they enter the restaurant. The ability to franchise successfully is also important, because franchising provides for more rapid growth than company operations typically can manage. The most successful chains tend to be marketing-Iriver organizations that strive to attain the critical mass of advertising needed to establish a strong presence in the target market. Finally, the caliber of a firen's Inanagement, both in the various functional areas and in the restaurant facilities themselves, greatly affects the firm's ability to respond to changing industry trends. The ability to coinpete on these many dimensions becomes particularly important as a narket segment matures and growth opportunities become more limited, Competitors in the hamburger segment of the fast-food industry employed a number of strategies to prepare for the anticipated decline in hamburger demand. Most diversified their offerings with breakfast and other special menus and developed new concepts such as drive- through-only units and home delivery, many atternpted to develop international markets for their products. Yet several other factors exacerbated the pressures facing the industry. The M The Naisbitt Guus 2hr Fare of France Taulane 25 Years Ahead in the Wor2070 Washington, DC: International Francaise Association. 1984p. 1 Daniel R. Lee." Why Scone Saceed Whore Others Tail." Comel Herriand Restawrand ton Charterly (Nienaber 1987. pp. 33-34. Sidney J.Peluca. "Fast Food Businesses Must Adulto Trends." Market Nels, September 25, 1987. p. 22 398 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS first was changing demographics. By the late 1980s, the aging of the baby boom generation (pcoplc born between 1945 and 1970) in the United States, and the increase in the elderly population were already having a significant impact on the industry's labor pool and the character of its customer base. Fast-food chains needed to develop product and service ofler- ings, as well as employment opportunities, that would meet the needs of an aging society. In addition, experts pointed out that many localities had become saturated with fast-food the result that suitable prime real estate either was not available or was quite costly to acquire. The cost of media advertising programs had also risen dramatically making it increasingly difficult for smaller chains without scale cconomies to afford this traditional tool for increasing customer awareness. Last, because American consumers re- mained health conscious, they would continue to demand innovative product offerings that were both convenient and nutritious. In discussing these trends, Ed Bradford, Roy Rogers' vice president and general manager, pointed out the dilemma facing many fast-food restaurant systems: While we must continue to develop new product offerings in anticipation of changing consumer preferences, consumers als expect us to offer them a dining expericuce which is both enjoyable and easily replicable throughout the system. Firms in this business must balance the pressures for innovation with the need to retain the integrity of the service concept which is at the core of their strategy Although the many pressures facing the industry were expected to limit opportunities for new national fast-food chains to enter the market, regional competitors like Roy Rogers were expected to enjoy some competitive advantage because of their ability to react quickly to trends, exploit relationships with local real estate developers and develop niche strategies well-suited to geographically limited markets. Roy Rogers Restaurants The Roy Rogers Restaurant system had a strategic mission that cmphasized hamburger and chicken products, a farnily orientation, and a high-pricc/high-value perception. The system was named for Roy Rogers, a country-and-western singer in the 1950s, best known for his TV and feature film appearances with his wife, Dale Evans, and his horse, Trigger. Although he had retired in the mid-1970s, he remained active in the entertainment industry and continued to make himself available to attend grand openings of new Roy Royers units and other special company events. Two of the Roy Rogers system's unique features were its salad bar and ils Fixin's Bar a condiment bar located in the middle of the store at which customers could add tomatoes lettuce, pickles, and other condiments to their sandwiches. At the end of 1986, chicken and hamburgers were the most popular products in Roy Rogers Restaurants in terms of sales revenues, accounting for just over 45% of all sales. Drinks, french fries, cole slaw, and roos beef accounted for another 40% of sales. Salads typically accounted for about 5% of sales With 345 company-owned and 214 franchised units as of 1987, Roy Rogers was thirteenth revenues among the top fast-food franchises. Following the arrival in 1986 of Ed Bradfort vice president and general manager, and Frank Martinez, vice president of franchising the Roy Rogers management team had developed a plan to double the system within five years Exhibit 4 shows the organization EJ Bradford had created by 1988. The division hoped Andrew Kostecka. "Restaucot Franchising in the Econy" Resor e s March 20, 1968, p. 194 CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 399 add 100 company units and 202 franchised units by 1992, the latter objective required the addition of 45 new franchisees. Like most franchises, Roy Rogers had a highly competitive selection process for its franchisees. Applicants, whether individuals or partnerships, were expected to complete a document summarizing their personal data, business experience, and independently verified statements of their personal assets, as well as to provide a plan for financing and managing the franchise. Prospective franchisees were expected to have a combined net worth of $500,000 or more, exclusive of their principal residences and personal property, with at least $150,000 in liquid assets available for investincnt. According to company statistics, 1% of the applicants succeeded in becoming franchisees. In addition to financial qualifications, applicants were evaluated on the basis of their previous restaurant experience, community standing, business accomplishments, and other factors such as character and motivation Individual owners and operating partners (who were required to have at least a 50% equity position in their partnership) were expected to devote substantially all of their time to the franchise. Franchisees with the resources to develop multiple sites were attractive applicants to franchisors like Roy Rogers, whose strategy emphasized rapid growth of their system. These franchisees were selected not only for their financial resources and operating experience but also for their expertise in local real estate markets and for the organizational structure they had in place to manage multiple units. Frank Martinez described the situation as follows: Franchisors lucing pressure to increase profitability and market share constantly struggle with the question of whether they should constrain the growth of their system by adhering to the pure fran chise form of single-unit ownership. While single-unit owners have strong incentives to provide the on-site supervision necessary to maintain the quality of their operations, more time and resources may be required to integrate them into the franchise system. On the other hand, franchisees with the Tesources in levelop multiple sites may he able to integrate new units into the system moro rapidly, although they may be less ellective managers because they do not have an operating role in their units. Since there were only a small number of franchisees with the resources and expertise required to operate multiple units, there was considerable competition within the franchisor community to secure multisite development agreements with them. The current population of 51 Roy's franchisees was comprised primarily of individual owner-operators of single or multiple units, with only eight out of the group organized as operating-investment partner ships and three organized as limited partnerships. Franchises were awarded for a period of 20 years and could be acquired either by constructing a new restaurant or, in selected instances, by purchasing an existing company owned or franchised facility. When matching franchisces to areas chosen for development, Roy Rogers tried to honor the geographical preferences of franchisces; however, they were expected to relocate if no local sites were available. The Franchise Agreement did not include a guarantee of territorial exclusivity. Other franchises or company-owned restaurants could be established within the same fenilory if Roy Rogers so desired. The initial fee to acquire a Roy Rogers franchise was $25,000, plus an option fee of $5,000 for the first unit. The total investment required, and income of a typical franchised unit are summarized in Exhibits 5 and 6. Roy's rcccived ongoing monthly royalties of 4% of gross sales from each franchisce as well as the franchisee's commitment to expend 5% of gross sales per month for advertising. Other fast-food chains charged initial franchise fees ranging from $15,000 to $40.000, and royalty fees ranging from 2% to 6% of gross sales. 400 CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS Some competitors also exacted fces of $20,000 to $50,000 for technical services related to the opening of a new unit and training of personnel. As of 1988. McDonald's, the recog- nized industry leader, charged an initial franchise fee of $22,500 but did not charge any technical fee. The Roy Rogers Franchise Agreement contained detailed provisions regarding the location, design, operation, and sale of franchised units. (A summary of the Roy Rogers Franchise Agreement is presented in Appendix B.) One of the essential elements of the contract, which was relevant to Jack Towle's request to discontinue the salad bar, was the requirement that the franchisee serve only the menu items specified by the company and follow all cupany specifications regarding the content, weight, pa products offered. Franchisees were visited approximately every two months by a Roy's fran- chise consultant, who inspected each operation for compliance with the system and assisted franchisees in making improvements. As of 1988, there were nine franchise consultants, each of whom had responsibility for approximately 25 restaurants. Since uniformity in both quality specifications and the varicty of product offerings was considered quite important to the integrity of the system, any deviations from the standard concept were considered serious infractions deserving of close monitoring by management. Although the company tried to be constructive in helping franchisees to rectify performance deficiencies or contract violations, the Franchise Agreement could be terminated if problems were not corrected within a reasonable period of time. While the company recognized the importance of preserving the Roy Rogers system, management also recognized the need to encourage innovation among the franchisees. As Frank Martinez, explained: While we do have a well-funded, in-house rescarch and development effort, we also recognize that our franchisccs have a great deal to contribute to the Roy Rogers organization. After all, they are entrepreneurs, many of whom have invested a good percentage of their personal wealth and careers in the Ray Rogers system. They also tend to have a unique perspective on the business, which comes from their daily contact with the customers, the suppliers, and the work force. While we want our franchisees to challenge us, lo question the status quo, we also want them to see the benefits of working through the organization to accomplish change. Our task as a franchisor is to harness their dedication, creativity, and entrepreneurial spirit in a way which can benefit both the individual franchisees and the system as a whole. One of the programs the company had introduced to manage the testing and implementation of new ideas was its Product Testing Policy (PTP). In the past, franchisees with suggestions for new products or operational improvements had simply submitted their suggestions to Roy's management for approval to introduce the new concept at their facility While many ideas had been rejected because they were not sufficiently well-developed or were incompatible with the company's strategy, the franchisees had not been given timely feedback about the reasons certain ideas were not selected for further evaluation. While the company viewed its role in managing the research and development (R&D) process as con sistent with its mandate to preserve the integrity of the system, some confusion had existed among the franchisees as to whether Roy's was truly committed to innova PTP represented an attempt to define the roles of the franchisec and Roy Rogers manage- ment in the product development process, while providing a mechanism for objective, timely evaluation of new idcas. To initiate the PTP, the franchiscc submitted a Product Test Request describing the new product idea or proposed operational improvement. The proposal was circulated within CASE A ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 401 Roy Rogers to the managers of franchising, marketing, and R&D. Ir the concept was deemed appropriate for further study, the company and franchisee jointly developed a plan for testing the new idea and judging its success. Although the new idea could be tested by either the company R&D department or the franchisee, the franchiseu was encouraged to carry out the test whenever leasible, Franchisees received no royalties or other remuneration for ideas they proposed that subscquently were selected for commercial development. Nev- ertheless, franchisees were quite receptive to the PTP and felt it improved communication and forced some necessary discipline and thoughtful analysis in judging new products. The Jack Towle Organization With 16 Roy Rogers units operating in urban Baltimore locations, Jack Towle was the third-largest Roy Rogers franchisee. He had been a franchisee for about six years. Ilis units were quite successful with average sales of $1,300,000 cach, 30% higher than the typical Roy Rogers restaurant. Jack Towle was unique among Roy Rogers franchisees in that he owned a number of restaurant franchises with multiple firms. While the Towle franchise contract with Roy Rogers prohibited him from purchasing franchises involving food offerings similar to Koy's, the various franchisors nevertheless did compete with one another for access to the Towlc real estate holdings in Baltimore. The Towle organization had considerable expertise in local real estate development and based its franchise development decisions on the profitability of the franchise and the nature of the working relationship with the franchisor. In order to secure the original contract with the Towle organization, Roy Rogers had agreed to reduce the standard royalty payment from 49 to 3% of gross sales for all of lack Towle's units. The Towle organization was one of a small percentage of franchisees with whom Roy Rogers had signed franchise development agreements. In 1987, Towic had agreed to develop 34 new units by the end of five years, resulting in a total of 50 units in operation by 1992. Towle had several Roy Rogers Restaurants under construction at the time that he approached tincz with the request to discontinue the salad bar at the newest facility. The Salad Bar Issue When Jack Towle had approached Frank Martinez at the Franchisee Advisory Council (FAC) meeting, he had argued his case hy pointing out that there were circumstances unique to his locations that warranted modification of the system. Towle had explained that the new facility being planned was going to be situated in a business district with considerable lunchtime tradlic. From past experience Towle recognized that adequate scating was impor- tant to urban customers when selecting a fast-food restaurant for lunch. Since salads sales typically represented only 5% of a unit's business, Towle had concluded that it would be preferable to eliminate the salad bar in the unit being planned and replace additional scats. With customer turnover at lunchtime occurring approximately every 12 minutes. Towle felt that the number of customers who would benefit from the additional seating capacity would outweigh those who could not order salad. Furthermore, with an average customer check estimated at $3.34, Towle felt his unit's revenues and profils would improve il the additional seating succeeded in attracting incremental lunchtime traffic. While the typical check of a salad-bar customer was higher, at S3.85, Towlo estimated that only 2.5% of the salad-bar customers would be lost i the salad bar were not available. As he contemplated possible responses to Towle's request, Frank Martinez was well the Franchise Agreement was unequivocal in prohibiting individual franchisecs CASE & ROY ROCERS RESTAURANTS 403 stations. Systems in which franchisees gain access to an entire business concept, marketing and operating plans and standards, as well as to continuing assistance from the franchisor, are called business format franchises. It is this latter type of franchise, of which Roy Rogers is an example, that is expected to contribute most to franchising's growth in the next decades. There is also a third type of franchising, called conversion franchising, in which established businesses becoine franchise outlets for established companies. The conversion franchisees pay lees to the franchise organization in the form of annual fixed fees and royalties in exchange for advertising support and other services. The Century 21 real estate company is a well-known example of this type of franchise. Franchise business now accounts for approximately one-third of all retail sales in the United States, more than $590 billion dollars, and is expected to account for half of all retail sales by the year 2000. Although franchising is most prevalent in the fast-food restaurant and lodging businesses, franchises offering such diverse services as housckeeping, automo- bile maintenance, and videocassette rentals have also cmerged and are contributing to franchising's dramatic growth. Franchise businesses are notable for dramatically low failure rates as compared with independent businesses. Approximately 97% of the franchises started in a given year are still in operation 12 months later, compared with 62% of indcpendent businesses. After 10 years, 90% of the franchises remain in operation, as compared with 18% of the independent businesses. Because of these impressive result, franchising is often described as a way of capturing many of the advantages of entrepreneurship while minimizing the risks. In its purest for franchising involves the purchase of a single-unil operation by an individual who invests his or her personal assets in the franchise and agrees to act as the ull-time owner/manager of the facility. In addition to singlc-unit franchisees. franchisors also may recruit individuals and firms with substantial experience and financial resources who have an interest in developing and operating multiple units in a particular geographical area. A franchisor may also award a master franchise contract, in which he or she sells the right to develop franchises in an entire territory to a middleman, who in turn sells the individual units. Whatever its structure, the relationship between the franchisor and franchisee is delin- cated in quile specific terms in the franchise contract, which is negotiated well before a unit opens for business. These agreements typically contain standards for site selection and design, operations, marketing, and sale of the facility. One of the critical factors distinguish ing the franchisor.franchisee relationship from that of an employer and employee is the fact that the franchisee is considered the owner of the unit and therefore, has the right to sell the franchise provided he or she can locale a qualified buyer. Franchise contracts typically allow the franchisor considerable latitude in approving prospective purchasers as well as terminating the franchise contracts of those operators who fail to adhere to the performance standards established for the franchise system, although this latitude is increasingly being restricted by the courts. A summary of the Roy Rogers Franchise Agreement has been included as Appendix B. Franchise offerings must adhere to regulatory standards established by the Federal Trade Commission and various state governments. Franchisors must provide prospective franchisees with a Uniform Franchise Ollering Circular (UFOC), whose purpose is to Huwan. Reill Business Bruneler" Restaruni Brick Morel 30. 1988, p. 2. Thic 404 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS provide extensive background on the franchisor's management team, the franchise concept and contract, and the financial position of the firm. The regulatory agencics scrutinize the financial data contained in the UFOC to ensure that no guarantees of financial performance are offered. This regulatory oversight came about in response to the fraudulent practices that became public during the franchising boom in the 1960s. Many investors were lured into purchasing franchises that, in fact, were pyramid schemes in which a franchisee's income was generated not by selling a product, but rather by recruiting new franchisccs. Appendix B Casewriter's Summary of the Franchise Agreement Franchise Option Agreement The construction and development of a Roy Rogers facility preceded the signing of the Franchise Agreement and were governed by a separate document called the Option Agreement. Following approval of an application, the first time franchisee paid a $5,000 option fee and submitted a written Site Approval Package that included a basic layout of the facility, acrial photographs, a marked map, a demographic alysis, a financing plan, and three-year cash flow projections. The Real Estate Department at Roy Rogers evaluated each site request and notified the franchisee of whether construction could proceed. Multiple submissions could be required before a site was finally selected. Roy Rogers supplied the general huilding plans for each new facility; franchisees were expected to retain local architects who could modify the plans to comply with local building codes. Franchisees were required to submit any such changes for review as well as to provide copies of all required permits. Franchisees independently negotiated to purchase or lease the land on which the facility was to reside. Once construction was underway, franchisees purchased the necessary equipment and provided Roy Rogers with documentation that the equipment conformed to the company's specifications. Although franchisees were free to purchase the equipment wherever they chose, Roy Rogers made available a list of qualified vendors whose products the company had already inspected. The Franchise Agreement The actual Franchise Agreement was typically executed within 30 days of a unit's opening, although technically it could be signed up to 180 days prior to opening. Upon opening the initial franchise foc of $25,000 was paid to the company Typically, 12 to 18 months elapsed between the approval of a franchisee and the opening of a new facility. The facility approval process was similar for franchisccs planning to renovate and convert existing restaurant buildings. Franchisees were expected to adhere to a strict timetable in opening units for business. Those who fell behind schedule in opening their restaurant could be charged a monthly ee of $3,000 until the unit became operational or, where applicable, until the agreement could be terminated and a replacement located. Both owners and lessces were required to pay the company an ongoing royalty fee of four percent (4%) of gross revenues once the unit becainc operational Financing As reflected in Exhibit 5, the total cost of building and equipping a new facility ranged between $976,000 and $1,374.000. Costs were somewhat lower for conver- sions or leasings. Franchisees were permitted to obtain some outside financing, provided the debt to total capital ratio for the franchise project did not exceed 65%. CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 405 Advertising and promotion Franchisees were expected to contribute to regional ad- vertising and promotion campaigns as well as to devole a specific percentage of their gross receipts to local advertising cfforts. The franchise agreement specified a minimum monthly contribution of 5% of gross sales for regional and local advertising expenditures combined. Of this total expenditure, a minimum of 1% of gross revenues were required to be spent on local marketing. The company could increase these spending requirements beyond the contractually established percentages only after obtaining the approval of two-thirds of the franchisees. Franchisees conducted local marketing programs independently, however, they were expected to secure Roy Rogers' approval of their annual plans, including any promotional materials to be used. The regional advertising programs were directed by the Marketing Department at Roy Rogers. In designing these programs, the company was not required to ensure that a particu lur facility hencfited directly from the funds it had contributed. The company also was not required to secure the franchisees approval of the plans or of any materials to be used Roy Rogers contributed a maximum of $7.500 from the regional advertising pool for expenses associated with the Grand Opening of a franchise. Should Roy Rogers, the film star after whom the franchise system was named, attend a Grand Opening or other special event at a restaurant, the franchisee was expected to pay for any expenses associated with his visit. Opening the unit Roy Rogers was contractually obligated to make the services of its franchise consultant available to a franchisec opening a new unit. The franchise consultant offered guidance concerning the many tasks involved in opening a new unit and provided training for the franchisee's employees. The franchise consultant was also free to requisition the services ol other Roy Rogers personnel whose assislance may be required to ensure a successful opening, Training The manager and assistant managers of each unit were required to com- plete the Roy Rogers training prograin before beginning work. Franchi lo absorb the costs of any training programs that the company deemed necessary to address deficiencies in the operation of a unit. They also were required to conduct tra for all employees using standard programs developed by Roy Rogers. Operations Franchisees were cxpected to adhere to the company's Operating Man- ual, which described the many performance, qualily, and design standards that constituted the Roy Rogers system. Company representatives had the authority to enter the restaurant unit without notice to verify that required procedures were being followed. The Operating Manual contained standards regarding the cleanliness and maintenance of the equipment and facility. Those who failed to operate the restau to obtain the highest health classification awarded by local authorities could be required to pay the costs of remedial training for the employees. The Operating Manual specified the days and hours during which each facility was required to operate and the uniforms to be worn by the employees. Franchisees were required to renovate the restaurant building, equipment, and signs at least once every five years to comply with the current image of the system. Furthermore, they were expected to carry out any modifications to the system that the company initiated during the period of the agreement. Signs of the type specified by the company were required to be placed prominently nour the unit. Company specifications concerning the restaurant menu were quite stringent. As part of the Franchise Agreement, the franchisce agreed to serve all of the menu items specified by the company, to follow all specifications regarding the contents, weight, and preparation of 406 CASE B ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS the food products, and to sell only products approved by Roy Rogers. The company provided the franchisee with the names of approved suppliers whose products conformed to specifications. Although franchisees were free to purchase supplies from any vendor they chose, they were required to submit new vendors' samples of product specifications for a qualifying evaluation. Sale of alcohol and display of entertainment devices such as video games or slot machines were prohibited unless approved by the company. The agreement also contained a provision that any taxes associated with the operation of the facility were to be paid promptly so the operation of the facility would not be jeopardized. Financial reporting Franchisccs were required to submit weekly sales reports by telephone and written sales reports to headquarters within 10 days of the end of each calen- dar month. Monthly written operating statements were expected to follow the preliminary reports within 25 days after the end of each month. A balance sheet and operating statements were submitted at the end of cach fiscal year. Roy Rogers could require that these reports dent auditors and could visit the franchise without notice to inspect the financial statements and supporting documentation. The Roy Rogers Operating Manual contained detailed specifications for the formats of any reports to be used Trademarks The trademarks owned by Roy Rogers included all "words, symbols. insignia, devices, designs, Trade Names, Service Marks, and rights in distinctive designs of buildings and signs" used to identify restaurants licensed to use the system and its products and services. Franchisees were prohibited from using the trademarks, any variations, or any names confusingly similar to the trademarks, in a manner not approved by Roy Rogers. ohibited from taking any steps to claim ownership of the trademarks. rms could not be used at a Roy Rogers facility without the company's approval Noncompete provision The franchisce and its key employees ordinarily were pro- hibited from taking part in any food business similar to Roy Rogers, located within a specific mile radius of their unit, for 18 months following the termination of the agreement. (Ownership of less than 1% of the stock of a public corporation in a similar business was allowed.) While operating the franchise, they were expected to avoid any outside activities that would prevent them from devoting full-time effort, i.e., 40 hours per weck, to the business. Relationship between franchisor and franchisee The franchisee was prohibited from holding itself out as an agent, legal representative, partner, subsidiary, joint venturer, or employee of Roy Rogers. The franchisec had no legal authority to enter into any binding agreeinents on the company's behalf. No fiduciary relationship existed between the fran- chisce and the company. Sale or transfer of interest Under the terms of the Franchise Agreement, Roy Rogers had the right to transfer or sell all or some of its rights and obligations as franchisor to another individual or entity. Because the franchisee had been selected for his or her indi- vidual business skills, financial resources, and personal character, however, he or she was not allowed to sell, transfer, or mortgage any interest in the franchise without the company's consent. Franchisees who violated this important clcment of the agreement could have their franchises terminated without notice. Roy Rogers was permitted to require that a franchisee offer to sell his or her interest to the company before making it available to other interested parties. In addition, franchisees ROY ROGERS UNIT FRANCHISE AGREEMENT. Standard For Other 28, 1997, p. 16. CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 407 could not offer the unit for sale to another party on more favorable terms than the company received. Franchisces were prohibited from advertising for prospective purchasers unless the company permitted them to do so. Prospective acquirers were expected to undertake the ap- plication process described earlier to ensure their fitness to operate the business. Roy Rogers received $3,000 to cover any legal and training expenses associated with the transfer. In addition, the original franchisee remained secondarily liable for all obligations relating to the Franchise for a period of 24 months following the sale to the new franchisec. Franchisves could organize as corporations only under circumstances prescribed by Roy Rogers. Such corporations could not sell any of their shares in a public offering, nor could any shares be transferred without the company's approval. The operuling partner of the franchise was required to retain 51% of the shares of the corporation holding the franchise, Violation of these requirements constituted grounds for terminating the franchise. The Franchise Agreement also contained provisions for transferring the franchise in the event of death or permanent incapacity of the franchisce. Termination of franchise There were several performance-related reasons for which a franchise could he lerininated without notice. Some of the more important were as follows: (1) in the event of bankruptcy or insolvency: and (2) in the event that a plan of liquidation or reorganization was filed, whether or not the plun subsequently was approved by thc courts. The franchise agreement specifically noted that the franchise could not be deemed an asset in any reorganization or bankruptcy proceeding The franchise could be terminated following a grace period for a number of perfor- mance-related reasons as well. Franchisees who failed to perform according to the terms of the agreement were given written notice of their deficiencies. Within the next 30 days, they were required either to resolve the problems cited or to show progress in correcting them. A franchisee could be terminated following written notice if he or she was more than 10 days late in making his or her required royalty or advertising payments to Koy Rogers. Other reasons for which a franchise could he terminated with notice included significant health and safely violations, failure to satisfy a legal judgment within 30 days after it became final, fal- sification of reports to the company, cousing to do business at the unit, or loss of possession or lease of the property on which the unit was located. A franchisee who received three or more notices regarding the same or similar deficiencies within a 12-month period could have his or her agreement terminated without notice. 408 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS EXHIBIT 1 Marriott Corporation's Balance Sheet, January 1, 1988 and January 2, 1987 1987 1986 Assets Curent assets Cash and temporary cash investments Accounts receivable Duc from alliliates Inventories, at lower of average cost or market Prepaid expenses Total current assets Property and equipment Building and improvements Leaschuld improvements Furniture and equipment Construction in progress $ 26.7 450.7 982 171.3 81.0 $ 8279 $ 15.6 493.6 125.8 186.5 97.6 S 919.1 469.5 323.6 1,064.9 680.0 690.2 $3.228.2 16501) $2,578.1 495.1 5012 5285 348.5 $5.370.5 Accumulated depreciation and amortization 3483 402.9 874.4 5918 5373 $2.754.7 _(547.3 S2.207.4 4845 3864 4032 2692 Investments in and advances to affiliates Assets held for sale Intangible assets Other assets $4,5793 LIABILITIES AND SHARETIOLDERS' EQUITY Current Liabilities Accounts payables Accrued payroll und benefits Other payables and accrued liabilities Current portion of long-term debt Total current liabilities 2119 3319 $ 5086 225.0 342.7 46,4 S1,122.7 2.498.8 212.1 289.5 436.6 Long-term debt Other long-lerm liabilities Deerred income Deferred income taxes $1.0175 1.6625 193.7 3165 3973 60 Shareholders' equity Common stock, 147.1 million shares issued Additional paid-in capital Retained earnings Treasury stock, al cost. 28.3 and 16.5 million shares, respectively Total shareholders' equity 147.1 87.3 1.150.2 (5742) $ 810.8 $5,370.5 S99 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 409 EXHIBIT 2 Marriott Corporation's Income Statement (Fiscal years ended January 1, 1988, January 2, 1987, and January 3, 1986) 1987 1986 1985 ($ IN MILLIONS, EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) Sales Loxtging Contract services Restaurants Total sales $2.57.1.3 2.969.0 879.9 $6.522.2 $2,233.1 2,236.1 797.3 $5,266,5 $1,898.4 1,586.3 757.0 $4.241.7 $2,409.4 2.798.4 797.5 S6,005.3 $2,017.4 2.081.2 718.2 $4.816.8 $1,712.6 1.467.7 678.8 $3.859.1 Operating Expenses Lodging Contract services Restaurants Total operating expenses Operating income Lodging Contract services Restaurants Total operating income $ 215.7 154.9 79.1 $ 449.7 S 263.9 170.6 82.4 $ 516,9 5 (74.5) (90.5) 47.0 S 398.9 $ 175.9 S 223.0 $ 1.67 $ 185.8 118.6 78.2 $ 382.6 $ (54.2) (75.6) 42.9 Corporate expenses Interest expense Interest income Income before income taxes $ (71.7) 160.3) 42.5 $360.2 $ 168.5 S 191.7 $ 1.40 Provision for income tax S 295.7 S 128.3 S 167.4 $ 1.24 Net income Earnings per share 410 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS EXHIBIT 3 Fast Food Restaurant Systems - 1986-1987 System wide Sales and Units RANKING BY SALES SYSTEMWIDE- SALES ($ IN MILLIONS) 1987 SALES AVERAGE COMPANY- UNIT Y WNED VOLUME ($ IN MILLIONS) CHAIN NAME (PARENT COMPANY) FRANCHISE- OWNED $ IN MILLIONS) $14.300 5.179 $1.433,000 1,092.000 4,800 7946 9.500 4.385 4,100 659,000 1.036 3,064 3.100 3,000 2,817 McDonald's Burger King (Pillsbury Co., Inc.) Kentucky Fried Chicken (PepsiCo. Inc.) Hardee (Imusco, Ltd.) Pizza Hut (PepsiCo., Inc.) Wendy's Domino's Pizza Taco Bell (PepsiCo., Inc.) Arby's (Royal Crown Cola, Inc.) Dunkin' Donuts Little Ceasar's Jack in the Box (Foodmaster, Inc.) Roy Rogers (Marriott Corp.) Church's Popeyes (A. Copeland Interests) 878,000 500,000 767.000 483.000 560,000 541,000 1,400 1,400 992 513 825" 1095 1,700 1.600 1.825 1.3939 677 891" 1,906 1.502 1,000 729 725 655 437.000 464,000 750,000 126 176" 512 717" 549 143 3281 2:10 14 568 580 460 1.000,00 390.00 663,000 418 80 162 380 Source: Adapted from "Restaurant Francising in the Emmy" Restaurant Business, March 20, 1988, p. 194. Data inchide international operarions. Ested by Restaurant Business Mugazine. CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 411 SYSTEMWIDE FRANCHISE-OWNED 1987 UNITS COMPANY-OWNED 3,151 794 9,911 5,179 6.760 1,385 7.522 1.901 5,621 2.912 6,163 3,848 4,279 2,682 1,848 963 2.863 1,259 1,109 1,473 202 1,949 3,300 2,589 3,170 1.209 1,646 1,669 1.820 897 441 639 1,640 1.379 258 583 1,486 344 1,072 112 239 414 618 730 412 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS EXHIBIT 4 Organization Chart Cordon Vice Oneral Manage EILRachen Fowly We Prude Developing Pan Van Versider r ising Dove Senhard Viser Rube Meer wil Vedeni Ang pe Reg Vios de Operos USEID KUMVERBANISMERET View Fancha Denise Bruce Fire Steve Bascon Bike Nyt Rap Hanbury Margar Regional ad heln s telee Nelere NY P ANY Unda S SS PAI Scorciary BE Lan Gier Pre Ware Ceno EXHIBIT 5 Cost Structure of a Franchise Unit CAPITAL INVESTMENT ESTIMATED COST RANGE Facility S500,000 $ 550,000 Land 225,000 500,000 Signs, cquipment, supplies 180,000 230,000 Inventory 8.000 10.000 Working capital 25,000 40,000 Insurance coverage 8,000 14,000 Franchise fee and option 30,000 30,000 $976,000 $1,374,000 Source: Roy Rogers, Uniform Franchise Offering Circular, 1987 ver in 26 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 413 EXHIBIT 6 Income Statement for a Typical Franchise (Leased Facility) T'ERCENTAGE TOTAL SALES AMOUNT 995 Sales Gross sales Discount/employee sales Total sales $1.050.000 6.300 $1,056,300 311,500 $ 744.800 100% Cost of goods (food purchase) Gross profit Expenses Salaries and benefits Rent Paper supplies Utilities Interest expense Equipment depreciation expense Promotions Maintenance Real estate tax Training General expenses Trash removal Cleaning supplies Cash register contract Amortization of franchise foc Winckrw cleaning Uniforms Bookkeeping Ollice supplies Dining room plants Roy Rogers' name fec Exterminal 267,000 97,600 46,400 41,100 29,300 24,100 17.800 15.000 4,600 4,200 2,200 1.900 1.800 1,500 1,250 1.200 1,000 SOD 800 500 300 200 $ 560.850 Royalties/Other Fees Royalties National advertising Total Royalties/Other fees Profit before Txx Incore lax 42.000 42.000 84,000 $ 99,950 49.975 Net income $ 49,975 396 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS CASE 8 Roy Rogers Restaurants It was 8:00 p.m. when Frank Martinez, vice president of franchising for Roy Rogers I Restaurants, finally left for home after his second day of meetings in March 1988 with the Franchisee Advisory Council. Although the decision to hold council meetings monthly, rather than biannually, imposed many new demands on himself and his managers, Martinez was encouraged to see a strong rapport developing between the Roy Rogers staff and the franchisees. Attendance at the meetings was increasing, and franchisees were expressing enthusiasm for the company's plans to expand the Roy Rogers system. Martinez was convinced that a successful partnership of Roy Rogers and the franchisees was necessary if the division was to meet the profit growth goal set by Roy Rogers' parent, the Marriott Corporation As he left the office, Frank Martinez, recalled his conversation with Jack Towlc. a major franchisee, who had approached him after the meeting with a request to eliminate the salad-har concept when he built his next Roy Rogers restaurant. Towle, who was Roy Rogers' third-largest franchisee, operated 16 units in major Balti also one of a small number of franchisees who was expected to play a critical role in the company's new growth strategy; he had recently signed a development agreement to build 34 new units hy the end of 1992. As Frank Martinez picked up the phone to inform Ed Brad ford, Roy Rogers' vice president and general manager, of Jack's request, he wondered how the organization should respond to an issue with such major implications for both the com pany and the interests of the 50 other franchisees. Marriott Corporation Roy Rogers Restaurants (often referred to within the company and in advertising as Roy's) was a subsidiary of the Marriott Corporation, a Washington, D.C.-based company which was founded in 1927 by J. Willard Marriott. From its beginnings as a small root beer stand Marriott had grown to $6.5 billion dollars in sales in 1987, with operations and franchises in 50 states and 24 countries. The company was in three principal businesses: lodging, com prised of both hotel operations and lifecare retirement communities, contract food services for businesses, hospitals, educational institutions, and airlines, and restaurants, comprised of family-oriented and fast-food restaurants as well as highway travel plazas. As a corporation Marriott was well-known for its expertise in applying creative financing strategies to real estate development activities. Exhibits 1 and 2 contain the company's 1987 financial statements and provide sales and income data by business sector. In its restaurant segment, Marriott operated or franchised more than 1,100 restaurants in 24 states. Its largest chain, Big Boy, was sold in 1987 to a major franchisee. The appro mately 220 company-owned units operating at the time of the sale were expected to be converted to a new restaurant concept. Roy Rogers, a fast-food chain serving hamburgers fried chicken, and roast beef sandwiches, had both franchises and company-owned facilities Patricia / Miowy MMM W preparadis case under the supervision of Pieser William / Brus, Je us the basis for class disculus recherchustio usine ither incrive or ineffective hundiiny w un administrative and Copyright 19NX by the President and Fellows of Harvard Collnye. Redur plus or mission to lice als onu -800-545-7685 or write larvard Business School Publisbion Boston, MA 172161. Na parlat his publication may here pred sarwina wioval system, used in a specsheel, cred in any form or by my mons-l e , mechanic photocopyice, T wing wherwise without the cubission of Harvnni Rusiness Schnel CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 397 locuted primarily in the Middle Atlantic states, Marriott's Sinallest chain in the restaurant segment was Hot Shoppes, which operated approximately 15 units in the Washington, D.C. area. Marriott also operated a large number of highway restaurants and merchandise outlets azas on 14 turnpikes. The restaurant facilities at the travel plazas included Big Boy and Roy Rogers Restaurants, as well as the fast-food restaurants of competitors such as Burger King. As of 1988, all of these units, including those of the competitors, were operated by Marriott's Travel Plazas Division rather than by the specific chain of which they were a part. The Fast-Food Industry The fast-food industry was comprised largely of restaurant chains, primarily franchises, that served harnburgers, chicken, pizza, sandwiches, or ethnic food such as Mexican or Chinese dishes. Franchising is explained in Appendix A. Chains serving hanburgers as their primary product offering dominated this industry, with approximately 31,511 units and $25.2 billion in sales as of 1986. Fast-food restaurants typically offered restaurant seating or takeout dining, including drive-through service. Takeout service was the most popular, with 60% to 65% of all fast food purchased for takeoul consumption. Fast- food dining had become a habit in American life, with nine out of ten people over the age of 12 eating in a fast-food restaurant regularly. Nevertheless, competition within the fast-food segment of the restaurant market had become fierce as the hamburger market matured, particularly with the entry of untraditional competitors such as supermarkets, convenience stores, and producers of prepackaged products suitable for microwave cooking. Exhibit 3 summarizes information about major competitors in the last-food industry in 1988. One industry analyst identified several factors that distinguish the successful restaurant ventures from the failures. First, the individual restaurant or chain must have a standard of product quality that is acceptable to the consulter. Of equal importance is the restaurant's ability to standardize its concept so that customers can predict what their dining experience will be like well before they enter the restaurant. The ability to franchise successfully is also important, because franchising provides for more rapid growth than company operations typically can manage. The most successful chains tend to be marketing-Iriver organizations that strive to attain the critical mass of advertising needed to establish a strong presence in the target market. Finally, the caliber of a firen's Inanagement, both in the various functional areas and in the restaurant facilities themselves, greatly affects the firm's ability to respond to changing industry trends. The ability to coinpete on these many dimensions becomes particularly important as a narket segment matures and growth opportunities become more limited, Competitors in the hamburger segment of the fast-food industry employed a number of strategies to prepare for the anticipated decline in hamburger demand. Most diversified their offerings with breakfast and other special menus and developed new concepts such as drive- through-only units and home delivery, many atternpted to develop international markets for their products. Yet several other factors exacerbated the pressures facing the industry. The M The Naisbitt Guus 2hr Fare of France Taulane 25 Years Ahead in the Wor2070 Washington, DC: International Francaise Association. 1984p. 1 Daniel R. Lee." Why Scone Saceed Whore Others Tail." Comel Herriand Restawrand ton Charterly (Nienaber 1987. pp. 33-34. Sidney J.Peluca. "Fast Food Businesses Must Adulto Trends." Market Nels, September 25, 1987. p. 22 398 CASE & ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS first was changing demographics. By the late 1980s, the aging of the baby boom generation (pcoplc born between 1945 and 1970) in the United States, and the increase in the elderly population were already having a significant impact on the industry's labor pool and the character of its customer base. Fast-food chains needed to develop product and service ofler- ings, as well as employment opportunities, that would meet the needs of an aging society. In addition, experts pointed out that many localities had become saturated with fast-food the result that suitable prime real estate either was not available or was quite costly to acquire. The cost of media advertising programs had also risen dramatically making it increasingly difficult for smaller chains without scale cconomies to afford this traditional tool for increasing customer awareness. Last, because American consumers re- mained health conscious, they would continue to demand innovative product offerings that were both convenient and nutritious. In discussing these trends, Ed Bradford, Roy Rogers' vice president and general manager, pointed out the dilemma facing many fast-food restaurant systems: While we must continue to develop new product offerings in anticipation of changing consumer preferences, consumers als expect us to offer them a dining expericuce which is both enjoyable and easily replicable throughout the system. Firms in this business must balance the pressures for innovation with the need to retain the integrity of the service concept which is at the core of their strategy Although the many pressures facing the industry were expected to limit opportunities for new national fast-food chains to enter the market, regional competitors like Roy Rogers were expected to enjoy some competitive advantage because of their ability to react quickly to trends, exploit relationships with local real estate developers and develop niche strategies well-suited to geographically limited markets. Roy Rogers Restaurants The Roy Rogers Restaurant system had a strategic mission that cmphasized hamburger and chicken products, a farnily orientation, and a high-pricc/high-value perception. The system was named for Roy Rogers, a country-and-western singer in the 1950s, best known for his TV and feature film appearances with his wife, Dale Evans, and his horse, Trigger. Although he had retired in the mid-1970s, he remained active in the entertainment industry and continued to make himself available to attend grand openings of new Roy Royers units and other special company events. Two of the Roy Rogers system's unique features were its salad bar and ils Fixin's Bar a condiment bar located in the middle of the store at which customers could add tomatoes lettuce, pickles, and other condiments to their sandwiches. At the end of 1986, chicken and hamburgers were the most popular products in Roy Rogers Restaurants in terms of sales revenues, accounting for just over 45% of all sales. Drinks, french fries, cole slaw, and roos beef accounted for another 40% of sales. Salads typically accounted for about 5% of sales With 345 company-owned and 214 franchised units as of 1987, Roy Rogers was thirteenth revenues among the top fast-food franchises. Following the arrival in 1986 of Ed Bradfort vice president and general manager, and Frank Martinez, vice president of franchising the Roy Rogers management team had developed a plan to double the system within five years Exhibit 4 shows the organization EJ Bradford had created by 1988. The division hoped Andrew Kostecka. "Restaucot Franchising in the Econy" Resor e s March 20, 1968, p. 194 CASE 8 ROY ROGERS RESTAURANTS 399 add 100 company units and 202 franchised units by 1992, the latter objective required the addition of 45 new franchisees. Like most franchises, Roy Rogers had a highly competitive selection process for its franchisees. Applicants, whether individuals or partnerships, were expected to complete a document summarizing their personal data, business experience, and independently verified statements of their personal assets, as well as to provide a plan for financing and managing the franchise. Prospective franchisees were expected to have a combined net worth of $500,000 or more, exclusive of their principal residences and personal property, with at least $150,000 in liquid assets available for investincnt. According to company statistics, 1% of the applicants succeeded in becoming franchisees. In addition to financial qualifications, applicants were evaluated on the basis of their previous restaurant experience, community standing, business accomplishments, and other factors such as character and motivation Individual owners and operating partners (who were required to have at least a 50% equity position in their partnership) were expected to devote substantially all of their time to the franchise. Franchisees with the resources to develop multiple sites were attractive applicants to franchisors like Roy Rogers, whose strategy emphasized rapid growth of their system. These franchisees were selected not only for their financial resources and operating experience but also for their expertise in local real estate markets and for the organizational structure they had in place to manage multiple units. Frank Martinez described the situation as follows: Franchisors lucing pressure to increase profitability and market share constantly struggle with the question of whether they should constrain the growth of their system by adhering to the pure fran chise form of single-unit ownership. While single-unit owners have strong incentives to provide the on-site supervision necessary to maintain the quality of their operations, more time and resources may be required to integrate them into the franchise system. On the other hand, franchisees with the Tesources in levelop multiple sites may he able to integrate new units into the system moro rapidly, although they may be less ellective managers because they do not have an operating role in their units. Since there were only a small number of franchisees with the resources and expertise required to operate multiple units, there was considerable competition within the franchisor community to secure multisite development agreements with them. The current population of 51 Roy's franchisees was comprised primarily of individual owner-operators of single or multiple units, with only eight out of the group organized as operating-investment partner ships and three organized as limited partnerships. Franchises were awarded for a period of 20 years and could be acquired either by constructing a new restaurant or, in selected instances, by purchasing an existing company owned or franchised facility. When matching franchisces to areas chosen for development, Roy Rogers tried to honor the geographical preferences of franchisces; however, they were expected to relocate if no local sites were available. The Franchise Agreement did not include a guarantee of territorial exclusivity. Other franchises or company-owned restaurants could be established within the same fenilory if Roy Rogers so desired. The initial fee to acquire a Roy Rogers franchise was $25,000, plus an option fee of $5,000 foStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access with AI-Powered Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started