Question: . Required: Critiques Overview please do it Top management commitment Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and green human resource management A Malaysian study 2051

. Required: Critiques Overview

please do it

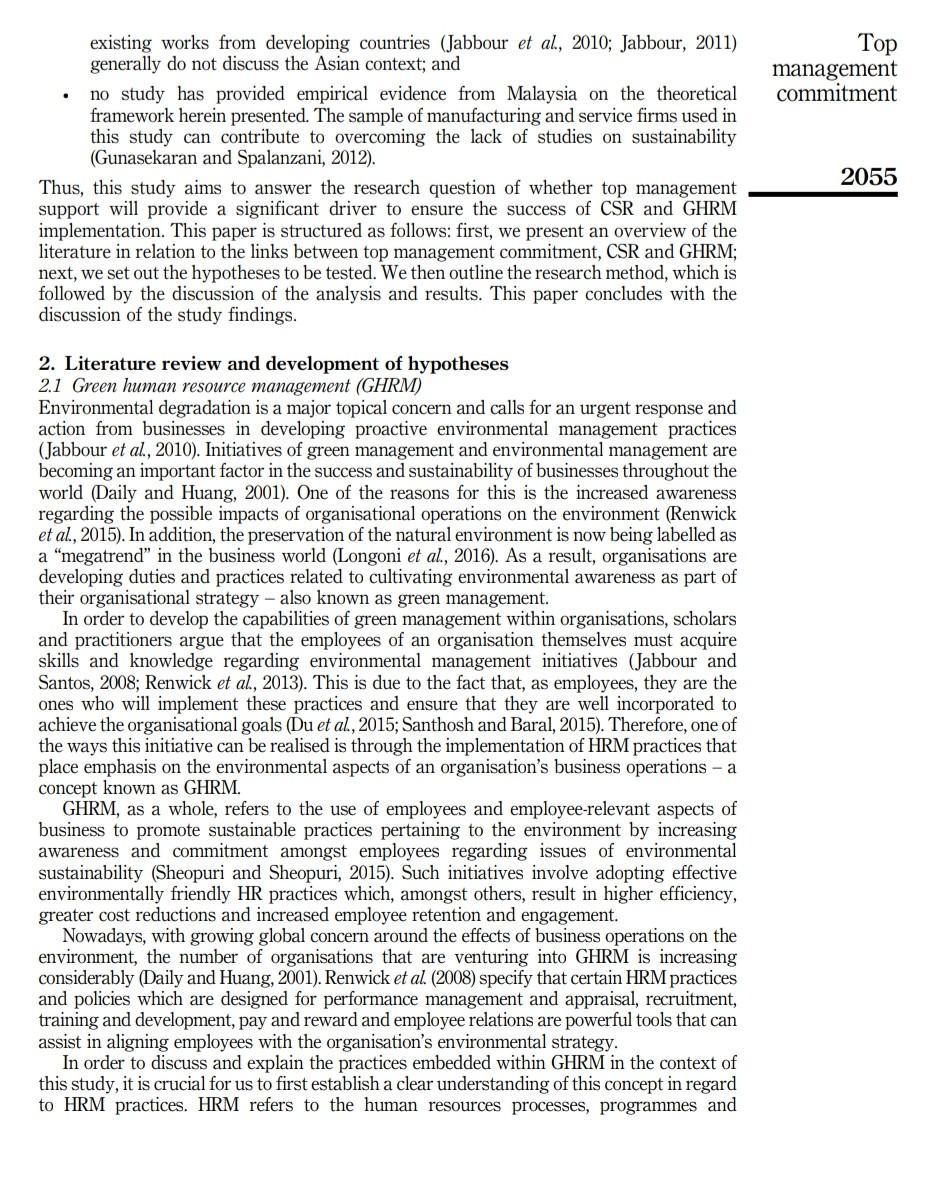

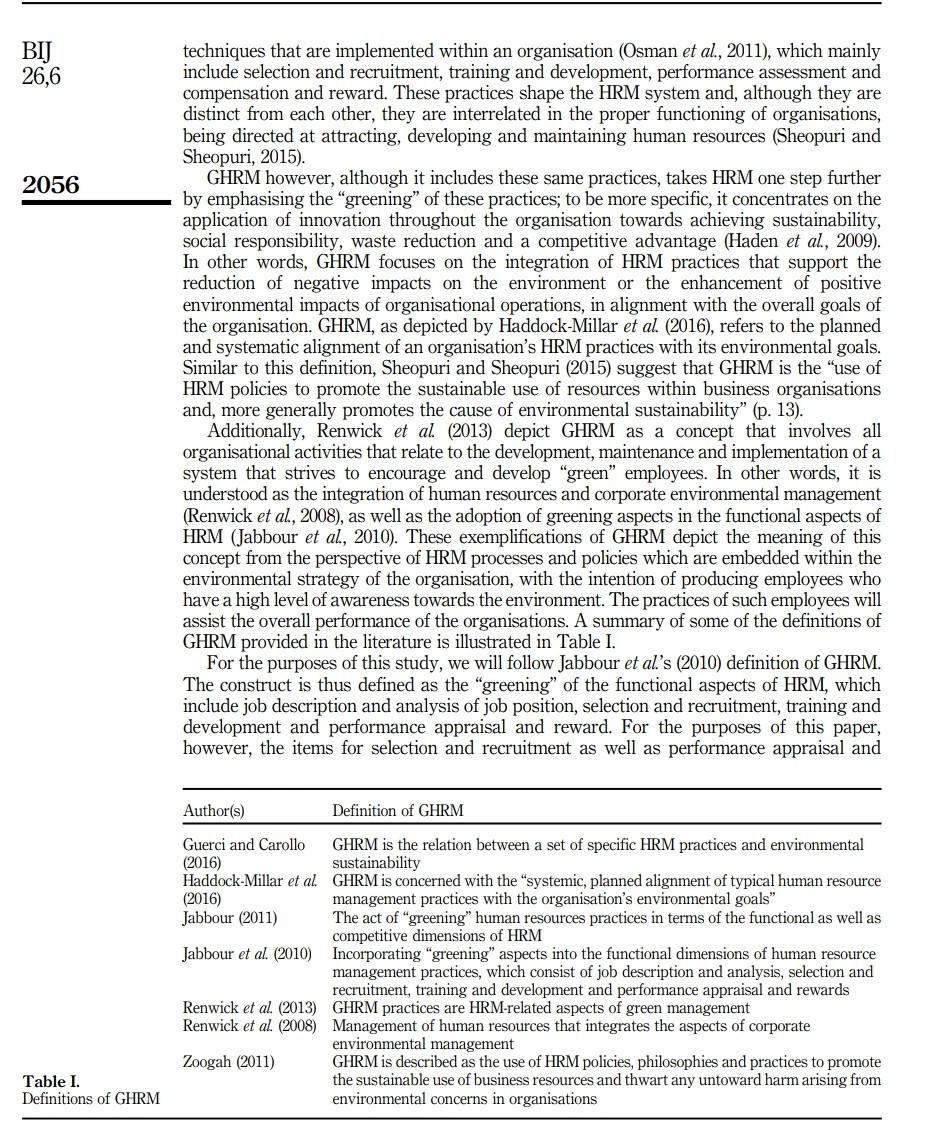

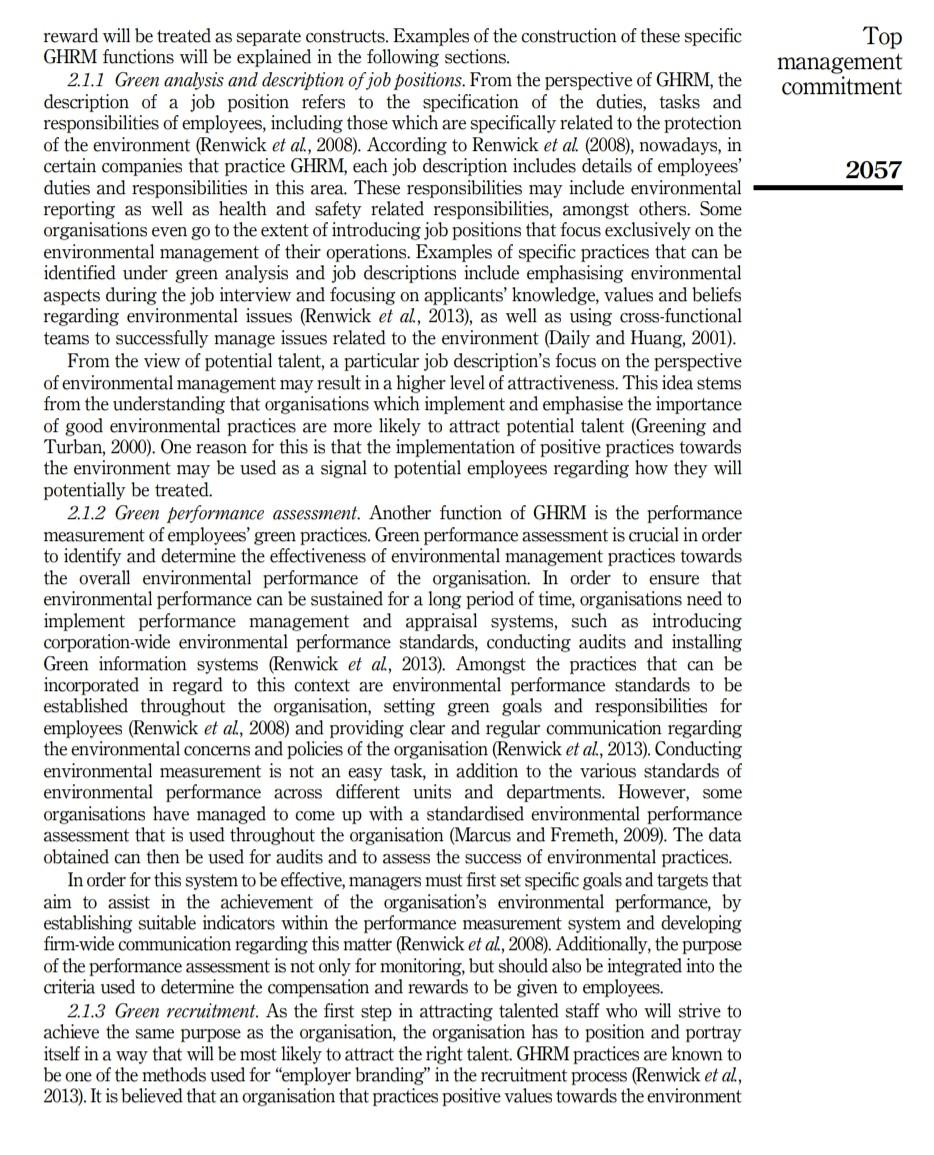

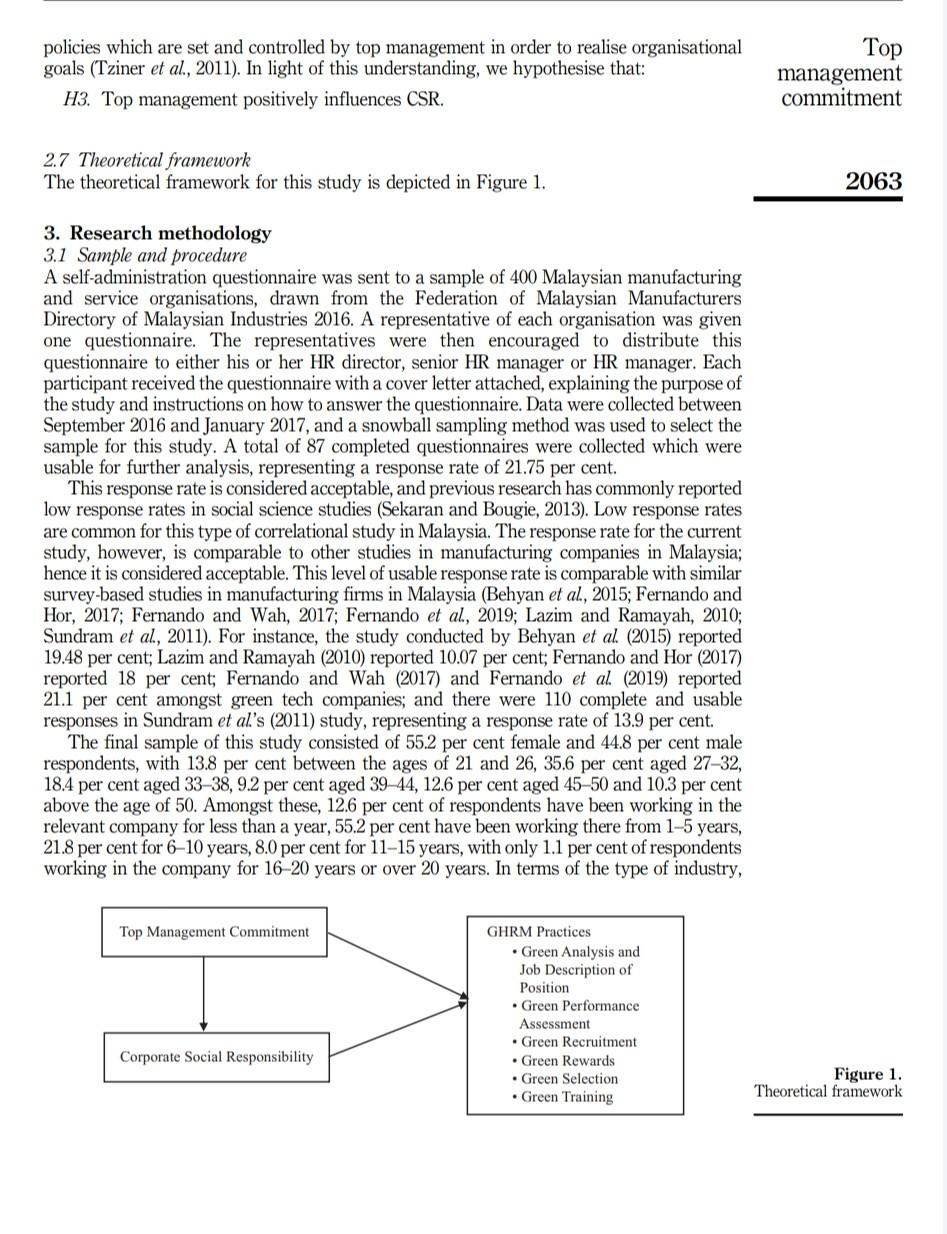

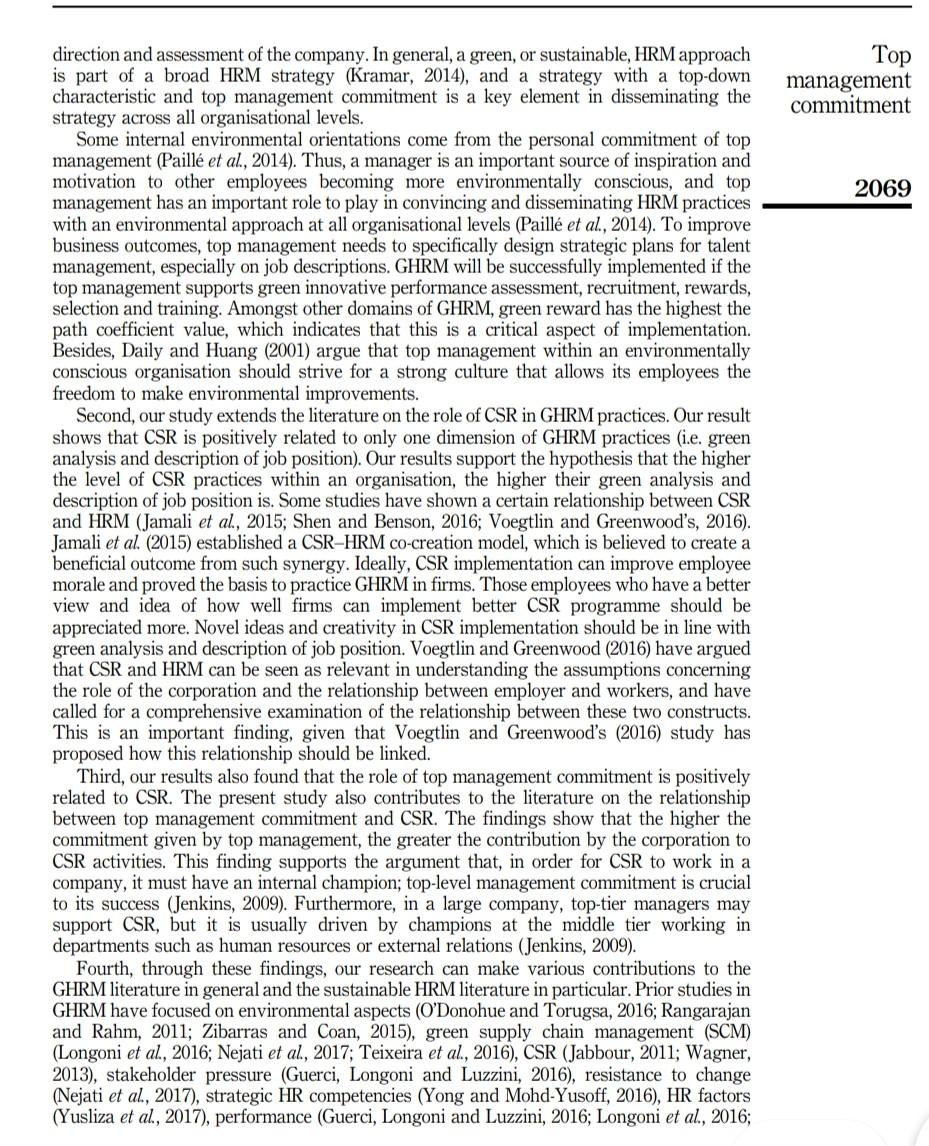

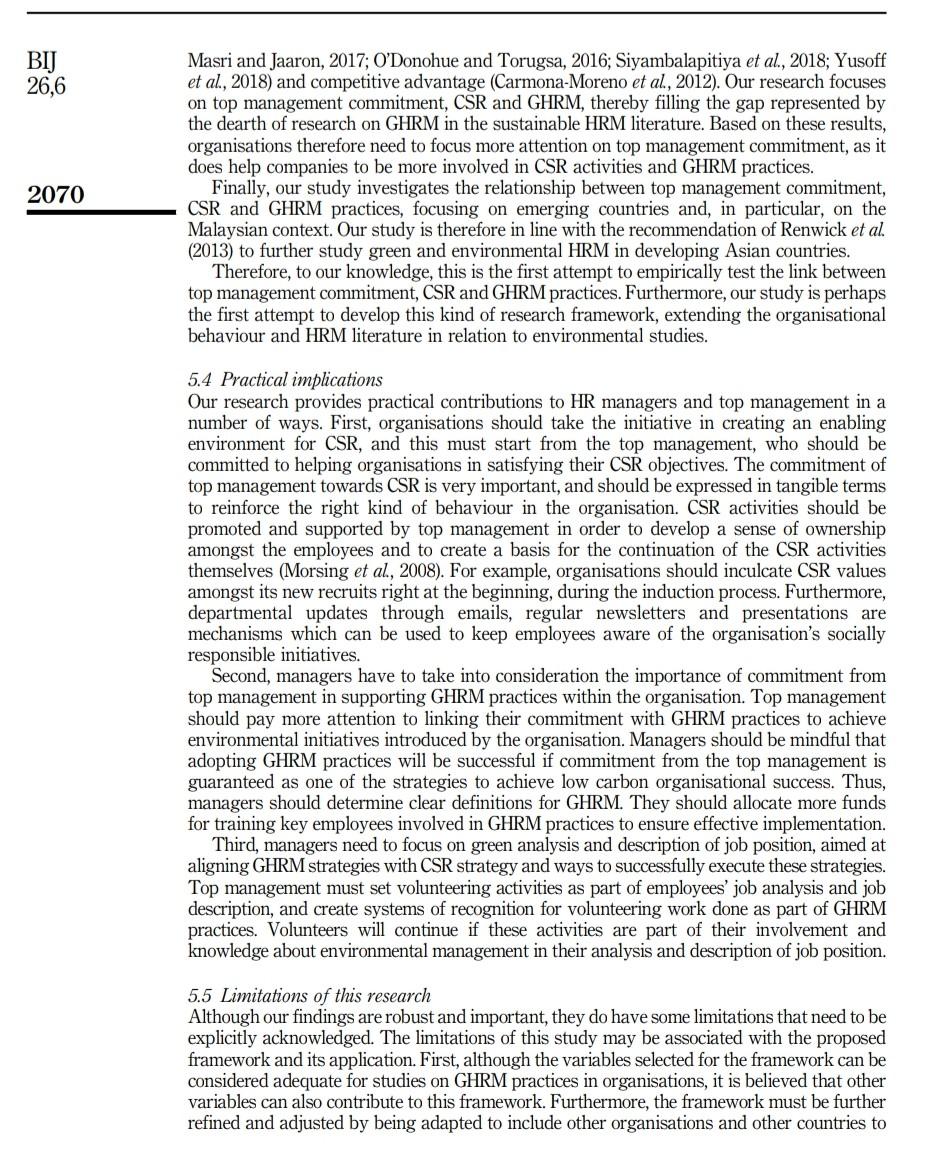

Top management commitment Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and green human resource management A Malaysian study 2051 Received 17 September 2018 Revised 22 January 2019 Accepted 5 February 2019 M.-Y. Yusliza School of Maritime Business and Management, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia Nurul Aimi Norazmi Maxshift Sdn. Bhd., Prai, Malaysia Charbel Jos Chiappetta Jabbour Montpellier Business School, Montpellier, France Yudi Fernando Faculty of Industrial Management, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Kuantan, Malaysia Olawole Fawehinmi School of Maritime Business and Management, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, and Bruno Michel Roman Pais Seles Department of Production Engineering, Sao Paulo State University (UNESP), So Paulo, Brazil Abstract Purpose - The purpose of this paper is to analyse the relationship between top management commitment, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and green human resource management (GHRM). Design/methodology/approach - A self-administered questionnaire was adopted to perform a systematic collection of data from manufacturing and service organisations in Malaysia. The partial least squares method was used for the conceptual framework of the study. Findings - The observed findings indicate a significant positive relationship between top management commitment and CSR, as well all dimensions of GHRM. However, counterintuitively, the relationship between CSR and GHRM was found not to be as significant as expected (except for CSR and green analysis/job description), which can be explained through the emerging perspective that CSR and HRM should be linked. Research limitations/implications - The findings provide insights as to the nature of GHRM and how it is affected by CSR and top management commitment in an emerging economy in this particular study, Malaysia. Moreover, the observed results highlight the crucial importance of top management commitment in implementing GHRM practices and CSR efficiently in order to create positive environmental performance. Originality/value The authors believe that, to date, no study has explored the links between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM using empirical data from Malaysia, as well as that this research is an important emerging topic for researchers, academicians and practitioners. Keywords Sustainability, Corporate social responsibility, Emerging economy, Top management commitment, Green human resource management Paper type Research paper Benchmarking: An International Journal Vol. 26 No. 6, 2019 pp. 2051-2078 Emerald Publishing Limited 1463-5771 DOI 10.1108/BIJ-09-2018-0283 This study was funded by Exploratory Research Grant Scheme from Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (Grant No. 203/PPAMC/6730125). BIJ 26,6 2052 1. Introduction Managing corporate environmental sustainability is a complex task, and can be considered one of the major challenges faced by organisations (Dubey et al., 2015). It has become imperative for any organisation not only to act responsibly towards the environment, but also to behave in a socially responsible manner while trying to achieve its economic goals (Gupta et al., 2018). In order to achieve proactive corporate environmental sustainability, organisations must mobilise their human resources in pursuing green objectives (Daily and Huang, 2001), thus linking environmental sustainability to the future of human resource management (HRM) (Jackson et al., 2014). Therefore, there exists a growing need for businesses to integrate environmental management into their HRM practices (Longoni et al., 2016; Jabbour and Santos, 2008; Paill et al., 2014; Renwick et al., 2008, 2013, 2015; Wagner, 2011, 2013). In response to these concerns, the concept of green human resource management (GHRM) has been devised (Ahmad, 2015; Gholami et al., 2016; Haddock-Millar et al., 2016; Jabbour, 2011; Jabbour and Jabbour, 2016; Jackson et al., 2011; Renwick et al., 2013, 2015; Yong and Mohd- Yusoff, 2016; Yusliza et al., 2017) as an answer to the crucial need for the expansion of the role of HRM in the pursuit of environmentally sustainable business practices. The term "green", added to the traditional idea of HRM, may include activities and practices that involve the preservation and conservation of the natural environment, avoidance or minimisation of environmental pollution and the generation of gardens and natural places (Jackson et al, 2011). In addition, the adoption of a management system focused on environmental sustainability is also believed to provide a competitive advantage for companies (Yang Spencer et al., 2013). In fact, studies have shown that GHRM practices affect voluntary behaviours towards the environment (Pinzone et al., 2016), implementation of environmental management systems (Jabbour et al., 2010; Wagner, 2013), environmental performance (Guerci, Longoni and Luzzini, 2016), green supply chain management (Jabbour and Jabbour, 2016; Longoni et al., 2016) and employees' green behaviour, both in-role and extra-role (Dumont et al., 2016). There are two main reasons that top management support is needed to practice corporate social responsibility (CSR) and GHRM in the context of emerging economies. First, the emerging world has received direct foreign investment to set up new manufacturing plants and create job opportunities. Some countries in the Asian region have contributed to sustainable development programmes, and most of these countries are categorised as emerging economies. Many manufacturing plants are now concentrated in the region, and green practices are attracting scholars' attention (Fernando et al., 2016). The industry should not consider revenue alone as the main indicator of business success, but perhaps more importantly need to ensure that the company employs sustainable and responsible business practices and activities for the wellbeing of stakeholders. Second, top management should lead the implementation of CSR and GHRM. These are the key drivers of GHRM implementation. The argument for the selection of Malaysia as the national setting for this topic is discussed in the following paragraphs. The emerging global landscape may be quite different from what we have seen over the past 100 years (Hong et al., 2018). Hong et al. (2018) also highlight that the dominant role of emerging economies is not to be underestimated. In a similar vein, focusing on a developing country is also important due to unique environmental conditions, including standard of living, level of labour productivity, degree of market failure and significant import and export growth rates (Ferdousi et al., 2018; Mersha, 1997). Parry et al. (1998, p. 741) states that "most future growth in emissions is expected to occur in the fast-developing regions of Asia" such as Malaysia. Furthermore, global economic power is shifting away from already established and mature economies towards emerging economies, which has been the new reality in recent years (Horwitz and Budhwar, 2015). This will inherently lead to an increase in the use of energy and natural resources in these regions. Emerging economies are expected to eventually produce 70 per cent of global GDP growth, and by the year 2025 their equity market capitalisation is expected to be 1.2 times greater than Top management commitment 2053 that of developed economies, to the tune of US$80bn dollars (Moe et al., 2010). This will cause a sharp increase in the demand for energy to stimulate this economic growth. Due to the combination of increased energy consumption and strong reliance on fossil fuels, the contribution of Southeast Asian countries - such as Malaysia - to climate change has increased significantly (Hansen and Nygaard, 2014; Rock and Angel, 2005). The location chosen for this study is Malaysia due to its impressive economic growth record, with rapid development in information and communication technologies and other infrastructures that require large input in terms of electricity (Lean and Smyth, 2010; Tang, 2008; Tang and Tan, 2013). Malaysia has a record average annual growth rate of CO2 emissions of slightly above 6 per cent, which is closely behind that of China, at 7.42 per cent (Sadorsky, 2014). Consequently, we focus on GHRM research in the context of a developing economy - Malaysia - in order to explore ways to create environmental sustainability through GHRM practices while also increasing GDP. Research interest in GHRM for emerging economies is increasing, as is research interest in benchmarking issues for emerging economies (Hong et al., 2018). Hong et al. (2018) further add that benchmarking can provide advice on which specific practices are transferrable from the context of advanced economies to their counterparts in emerging economies. The GHRM literature is largely based on Western countries and, given the importance of Asian economic development to environmental management, this is an important gap for future studies to reduce (Renwick et al., 2013), particularly in emerging countries such as Malaysia. GHRM has been practised and researched in the USA (Rangarajan and Rahm, 2011), European countries (Guerci and Carollo, 2016; Guerci, Longoni and Luzzini, 2016; fuerci, Montanari, Scapolan and Epifanio, 2016; Haddock-Millar et al., 2016; Pinzone et al., 2016; Wagner, 2013; Zibarras and Coan, 2015), Middle Eastern countries (Al Kerdawy, 2018; Nejati et al., 2017), certain Asian countries (Dumont et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Luu, 2018; Mishra, 2017; Mishra et al., 2014; Mukherjee and Chandra, 2018; Ragas et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2016; Siyambalapitiya et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2017), with a lack of studies from Southeast Asia, especially Malaysia (Yong and Mohd-Yusoff, 2016; Yusliza et al., 2017; Yusoff et al., 2018). Therefore, GHRM practices may be transferrable to Malaysia to the extent that such practices pass the test of generalisability. Finding the key to sustainable management of people, processes and products in emerging markets is not an easy task (Singh, 2018) and organisations continually have to develop different strategies to remain competitive in business. Despite the growing importance GHRM has to modern businesses and the emphasis placed on this concept from a scholarly perspective, there is still a dearth of literature pertaining to this crucial area (Jackson et al., 2014; Renwick et al., 2015). Moreover, the available work focusing on GHRM is either conceptual or theoretical (Jabbour et al., 2010, Renwick et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2014; Renwick et al., 2015). Lengnick-Hall and Lengnick-Hall (2003) urge a change in the role of GHRM to correspond to the new requirements of emerging economies. Moreover, Ji et al. (2012) argue that the interaction between firms' environmental attitude and HRM practices in emerging economies remains unclear. However, as previously mentioned, effective implementation of GHRM practices, as with other HRM practices within an organisation, requires efficiency and commitment from the management team and, more specifically, top management (Green et al., 2012) - a classical prerequisite of green initiatives at the organisational level (Zutshi and Sohal, 2004). Sangwan and Choudhary (2018) highlight that a performance measure, or a set of performance measures, can be used to determine the efficiency and/or effectiveness of a system, or to compare challenging alternative systems for benchmarking. Singh et al. (2013) identify top management commitment as one of the 11 performance measures for environmentally conscious manufacturing. Not only taking top management commitment as a major consideration, but taking it one step further, this study incorporates the concept of top management commitment specifically in terms of greening, or HRM practices that are environment-focused (Daily and Huang, 2001; Moini et al., 2014). Wei and Lau (2005) reveal BIJ 26,6 2054 that changes in top management commitment in emerging economies lead to greater adoption of strategic HRM practices. It is proposed that GHRM is part of a strategic HRM context (Arago and Jabbour, 2017). Strategic HRM involves the design and implementation of a consistent set of internal policies and practices to ensure that the human resources of a company contribute to the achievement of its business goals (Huselid et al., 1997), while GHRM denotes the association and support of HRM practices for environmental management development within an organisation (Renwick et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2011). With the presence of top management commitment, companies will be able to effectively implement their green initiatives - or, from the perspective of this study, GHRM practices - in order to achieve positive environmental performance (Yang Spencer et al, 2013). The reason for this is that it is the top managers of a company who are able to enforce practices and policies to be implemented within the organisation in order to realise the company's goals and objectives. With this enforcement, employees will be more aware of and inclined to adopt these practices in their daily operations, in the pursuit of achieving environmental goals. Furthermore, the formalisation of the "greening" of HRM practices will provide clearer guidelines for effective implementation across all levels of the organisation. From the overall business sustainability perspective, HRM should be linked to CSR (e.g. Jamali et al., 2015; Voegtlin and Greenwood, 2016). Consequently, GHRM practices can also be considered as part of firms' CSR strategy. Furthermore, there is a dearth of understanding in the evolution of CSR, particularly in emerging economies; hence, this area deserves scholarly attention (Wang et al., 2016). It is believed that the process of CSR will be different between developed and emerging economies, due to the different underlying social agreements and institutional contexts (Tilcsik and Marquis, 2013; Wang et al, 2016; Zhang and Luo, 2013). For instance, it is argued that CSR activities are not usually made known to stakeholders in emerging economies (Mellahi and Wood, 2003; Rettab et al, 2009). Additionally, it is opined that organisations in emerging economies may tend towards unethical practices due to the pressure to attain sustainable and global competitive advantage (Rettab et al., 2009). CSR is not considered an area that is optional for companies to engage in, but these days is rather considered to be a business imperative. This is so much the case that it has become a standard part of company strategy (Tziner et al., 2011). However, to the best of our knowledge, previous literature has failed to provide a clear link (if any) between CSR and GHRM which, if established, could provide practitioners with steps and guidelines as to how organisations may be able to improve their CSR through the implementation of GHRM practices, or vice-versa. This could provide a better understanding as to how the adoption of CSR may lead to more effective implementation of GHRM practices, which is what this study will explore. The focus of this study therefore emphasises the direct influence of top management commitment on GHRM practices, as well as the relationship between top management commitment and CSR and, finally, the relationship between CSR and GHRM. It should be highlighted that after reviewing the most significant works in the field of GHRM (such as Daily and Huang, 2001; Jackson et al., 2011, 2014; Renwick et al., 2013, 2015), no similar research was found. In addition, when analysing the literature on CSR and HRM, we found no clear mention of GHRM (e.g. Voegtlin and Greenwood, 2016). Finally, the literature on the relevance of top management's commitment to GHRM is not clear regarding the potential relationship with CSR perspectives (Jabbour et al., 2010; Zutshi and Sohal, 2004; Daily and Huang, 2001). In this context, this work offers an original perspective on the relationships amongst top management commitment, CSR and GHRM. Its relevance can be justified as follows: no study, to the best of our knowledge, has so far explored the relationships herein considered; the existing literature on GHRM is largely influenced by perspectives from developed countries (Jackson et al., 2014; Longoni et al., 2016; Haddock-Millar et al., 2016), while Top management commitment existing works from developing countries (Jabbour et al, 2010; Jabbour, 2011) generally do not discuss the Asian context; and no study has provided empirical evidence from Malaysia on the theoretical framework herein presented. The sample of manufacturing and service firms used in this study can contribute to overcoming the lack of studies on sustainability (Gunasekaran and Spalanzani, 2012). Thus, this study aims to answer the research question of whether top management support will provide a significant driver to ensure the success of CSR and GHRM implementation. This paper is structured as follows: first, we present an overview of the literature in relation to the links between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM; next, we set out the hypotheses to be tested. We then outline the research method, which is followed by the discussion of the analysis and results. This paper concludes with the discussion of the study findings. 2055 2. Literature review and development of hypotheses 2.1 Green human resource management (GHRM) Environmental degradation is a major topical concern and calls for an urgent response and action from businesses in developing proactive environmental management practices (Jabbour et al., 2010). Initiatives of green management and environmental management are becoming an important factor in the success and sustainability of businesses throughout the world (Daily and Huang, 2001). One of the reasons for this is the increased awareness regarding the possible impacts of organisational operations on the environment (Renwick et al., 2015). In addition, the preservation of the natural environment is now being labelled as a "megatrend" in the business world (Longoni et al., 2016). As a result, organisations are developing duties and practices related to cultivating environmental awareness as part of their organisational strategy - also known as green management. In order to develop the capabilities of green management within organisations, scholars and practitioners argue that the employees of an organisation themselves must acquire skills and knowledge regarding environmental management initiatives (Jabbour and Santos, 2008; Renwick et al., 2013). This is due to the fact that, as employees, they are the ones who will implement these practices and ensure that they are well incorporated to achieve the organisational goals (Du et al., 2015; Santhosh and Baral, 2015). Therefore, one of the ways this initiative can be realised is through the implementation of HRM practices that place emphasis on the environmental aspects of an organisation's business operations - a concept known as GHRM. GHRM, as a whole, refers to the use of employees and employee-relevant aspects of business to promote sustainable practices pertaining to the environment by increasing awareness and commitment amongst employees regarding issues of environmental sustainability (Sheopuri and Sheopuri, 2015). Such initiatives involve adopting effective environmentally friendly HR practices which, amongst others, result in higher efficiency, greater cost reductions and increased employee retention and engagement. Nowadays, with growing global concern around the effects of business operations on the environment, the number of organisations that are venturing into GHRM is increasing considerably (Daily and Huang, 2001). Renwick et al. (2008) specify that certain HRM practices and policies which are designed for performance management and appraisal, recruitment, training and development, pay and reward and employee relations are powerful tools that can assist in aligning employees with the organisation's environmental strategy. In order to discuss and explain the practices embedded within GHRM in the context of this study, it is crucial for us to first establish a clear understanding of this concept in regard to HRM practices. HRM refers to the human resources processes, programmes and BIJ 26,6 2056 techniques that are implemented within an organisation (Osman et al., 2011), which mainly include selection and recruitment, training and development, performance assessment and compensation and reward. These practices shape the HRM system and, although they are distinct from each other, they are interrelated in the proper functioning of organisations, being directed at attracting, developing and maintaining human resources (Sheopuri and Sheopuri, 2015). GHRM however, although it includes these same practices, takes HRM one step further by emphasising the greening of these practices; to be more specific, it concentrates on the application of innovation throughout the organisation towards achieving sustainability, social responsibility, waste reduction and a competitive advantage (Haden et al., 2009). In other words, GHRM focuses on the integration of HRM practices that support the reduction of negative impacts on the environment or the enhancement of positive environmental impacts of organisational operations, in alignment with the overall goals the organisation. GHRM, as depicted by Haddock-Millar et al. (2016), refers to the planned and systematic alignment of an organisation's HRM practices with its environmental goals. Similar to this definition, Sheopuri and Sheopuri (2015) suggest that GHRM is the use of HRM policies to promote the sustainable use of resources within business organisations and, more generally promotes the cause of environmental sustainability" (p. 13). Additionally, Renwick et al. (2013) depict GHRM as a concept that involves all organisational activities that relate to the development, maintenance and implementation of a system that strives to encourage and develop "green" employees. In other words, it is understood as the integration of human resources and corporate environmental management (Renwick et al., 2008), as well as the adoption of greening aspects in the functional aspects of HRM (Jabbour et al, 2010). These exemplifications of GHRM depict the meaning of this concept from the perspective of HRM processes and policies which are embedded within the environmental strategy of the organisation, with the intention of producing employees who have a high level of awareness towards the environment. The practices of such employees will assist the overall performance of the organisations. A summary of some of the definitions of GHRM provided in the literature is illustrated in Table I. For the purposes of this study, we will follow Jabbour et al's (2010) definition of GHRM. The construct is thus defined as the "greening" of the functional aspects of HRM, which include job description and analysis of job position, selection and recruitment, training and development and performance appraisal and reward. For the purposes of this paper, however, the items for selection and recruitment as well as performance appraisal and Author(s) Definition of GHRM Guerci and Carollo GHRM is the relation between a set of specific HRM practices and environmental (2016) sustainability Haddock-Millar et al GHRM is concerned with the systemic, planned alignment of typical human resource (2016) management practices with the organisation's environmental goals" Jabbour (2011) The act of "greening human resources practices in terms of the functional as well as competitive dimensions of HRM Jabbour et al. (2010) Incorporating "greening aspects into the functional dimensions of human resource management practices, which consist of job description and analysis, selection and recruitment, training and development and performance appraisal and rewards Renwick et al. (2013) GHRM practices are HRM-related aspects of green management Renwick et al. (2008) Management of human resources that integrates the aspects of corporate environmental management Zoogah (2011) GHRM is described as the use of HRM policies, philosophies and practices to promote the sustainable use of business resources and thwart any untoward harm arising from environmental concerns in organisations Table I. Definitions of GHRM Top management commitment 2057 reward will be treated as separate constructs. Examples of the construction of these specific GHRM functions will be explained in the following sections. 2.1.1 Green analysis and description of job positions. From the perspective of GHRM, the description of a job position refers to the specification of the duties, tasks and responsibilities of employees, including those which are specifically related to the protection of the environment (Renwick et al., 2008). According to Renwick et al. (2008), nowadays, in certain companies that practice GHRM, each job description includes details of employees' duties and responsibilities in this area. These responsibilities may include environmental reporting as well as health and safety related responsibilities, amongst others. Some organisations even go to the extent of introducing job positions that focus exclusively on the environmental management of their operations. Examples of specific practices that can be identified under green analysis and job descriptions include emphasising environmental aspects during the job interview and focusing on applicants' knowledge, values and beliefs regarding environmental issues (Renwick et al., 2013), as well as using cross-functional teams to successfully manage issues related to the environment (Daily and Huang, 2001). From the view of potential talent, a particular job description's focus on the perspective of environmental management may result in a higher level of attractiveness. This idea stems from the understanding that organisations which implement and emphasise the importance of good environmental practices are more likely to attract potential talent (Greening and Turban, 2000). One reason for this is that the implementation of positive practices towards the environment may be used as a signal to potential employees regarding how they will potentially be treated. 2.1.2 Green performance assessment. Another function of GHRM is the performance measurement of employees' green practices. Green performance assessment is crucial in order to identify and determine the effectiveness of environmental management practices towards the overall environmental performance of the organisation. In order to ensure that environmental performance can be sustained for a long period of time, organisations need to implement performance management and appraisal systems, such as introducing corporation-wide environmental performance standards, conducting audits and installing Green information systems (Renwick et al, 2013). Amongst the practices that can be incorporated in regard to this context are environmental performance standards to be established throughout the organisation, setting green goals and responsibilities for employees (Renwick et al, 2008) and providing clear and regular communication regarding the environmental concerns and policies of the organisation (Renwick et al., 2013). Conducting environmental measurement is not an easy task, in addition to the various standards of environmental performance across different units and departments. However, some organisations have managed to come up with a standardised environmental performance assessment that is used throughout the organisation (Marcus and Fremeth, 2009). The data obtained can then be used for audits and to assess the success of environmental practices. In order for this system to be effective, managers must first set specific goals and targets that aim to assist in the achievement of the organisation's environmental performance, by establishing suitable indicators within the performance measurement system and developing firm-wide communication regarding this matter (Renwick et al, 2008). Additionally, the purpose of the performance assessment is not only for monitoring, but should also be integrated into the criteria used to determine the compensation and rewards to be given to employees. 2.1.3 Green recruitment. As the first step in attracting talented staff who will strive to achieve the same purpose as the organisation, the organisation has to position and portray itself in a way that will be most likely to attract the right talent. GHRM practices are known to be one of the methods used for employer branding" in the recruitment process (Renwick et al., 2013). It is believed that an organisation that practices positive values towards the environment policies which are set and controlled by top management in order to realise organisational goals (Tziner et al., 2011). In light of this understanding, we hypothesise that: H3. Top management positively influences CSR. Top management commitment 2.7 Theoretical framework The theoretical framework for this study is depicted in Figure 1. 2063 3. Research methodology 3.1 Sample and procedure A self-administration questionnaire was sent to a sample of 400 Malaysian manufacturing and service organisations, drawn from the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers Directory of Malaysian Industries 2016. A representative of each organisation was given one questionnaire. The representatives were then encouraged to distribute this questionnaire to either his or her HR director, senior HR manager or HR manager. Each participant received the questionnaire with a cover letter attached, explaining the purpose of the study and instructions on how to answer the questionnaire. Data were collected between September 2016 and January 2017, and a snowball sampling method was used to select the sample for this study. A total of 87 completed questionnaires were collected which were usable for further analysis, representing a response rate of 21.75 per cent. This response rate is considered acceptable, and previous research has commonly reported low response rates in social science studies (Sekaran and Bougie, 2013). Low response rates are common for this type of correlational study in Malaysia. The response rate for the current study, however, is comparable to other studies in manufacturing companies in Malaysia; hence it is considered acceptable. This level of usable response rate is comparable with similar survey-based studies in manufacturing firms in Malaysia (Behyan et al., 2015; Fernando and Hor, 2017; Fernando and Wah, 2017, Fernando et al., 2019; Lazim and Ramayah, 2010; Sundram et al., 2011). For instance, the study conducted by Behyan et al. (2015) reported 19.48 per cent; Lazim and Ramayah (2010) reported 10.07 per cent; Fernando and Hor (2017) reported 18 per cent; Fernando and Wah (2017) and Fernando et al. (2019) reported 21.1 per cent amongst green tech companies; and there were 110 complete and usable responses in Sundram et al's (2011) study, representing a response rate of 13.9 per cent. The final sample of this study consisted of 55.2 per cent female and 44.8 per cent male respondents, with 13.8 per cent between the ages of 21 and 26, 35.6 per cent aged 2732, 18.4 per cent aged 33-38, 9.2 per cent aged 39-44, 12.6 per cent aged 45-50 and 10.3 per cent above the age of 50. Amongst these, 12.6 per cent of respondents have been working in the relevant company for less than a year, 55.2 per cent have been working there from 1-5 years, 21.8 per cent for 6-10 years, 8.0 per cent for 11-15 years, with only 1.1 per cent of respondents working in the company for 16-20 years or over 20 years. In terms of the type of industry, Top Management Commitment GHRM Practices . Green Analysis and Job Description of Position Green Performance Assessment . Green Recruitment . Green Rewards . Green Selection . Green Training Corporate Social Responsibility Figure 1. Theoretical framework BIJ 26,6 amongst the sample companies of this study, 72.4 per cent were in the manufacturing industry, which accounts for 63 companies, while the remaining 27.6 per cent (24 companies) were in the service industry. All companies surveyed are ISO 14001 certified. ISO 14001 defines environmental performance as assessable results of the environmental management systems linking to the management of the environmental facets performed by the enterprise, based on its environmental strategies and aims (Sangwan and Choudhary, 2018). 2064 3.2 Questionnaire items We used a five-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) to measure all constructs. The GHRM variables assessed were adapted from Jabbour et al. (2010), and consisted of six dimensions: green analysis and description of job position, green performance assessment, green recruitment, green rewards, green selection and green training. Measures of top management commitment were adapted from Digalwar et al. (2013). The measurement of CSR was adapted from Chang and Chen (2012). Using a self-administered survey and a stratified random sampling technique, the data obtained were then analysed using the SmartPLS 2.0 software in order to investigate and determine the nature of the relationship between the three variables included in this study. 4. Findings To achieve the objective of this paper, a quantitative method was employed, using the statistical package of structural equation modelling (SEM) with the partial least square (PLS) method. The software used is included as part of a component-based SEM method (Hair et al., 2014). This software is useful since it makes fewer demands in terms of sample size. According to Hair et al. (2014), PLS-SEM offers remarkable multivariate data analysis because of the statistical software's ability to examine the structural model with acceptable power using a very small sample. Kock and Hadaya (2018) posit that strong path coefficients at the population level tend to require very small sample sizes. Ramli et al. (2018) have concurred with Hair et al. (2014) that 5 to 10 cases are needed for a complex model. Despite the fact that PLS-SEM is not very sensitive to assumptions of normality, it is worth considering the statistical power of predictors in the model in terms of sample size (Fernando and Chukai, 2018). Thus, SmartPLS 3.2 software is used here for pl 4.1 Measurement model 14/29 The validation of the measurement quality was examined to determine the constructs. For this purpose, we analysed the composite reliability scores and found that all constructs had a recommended score higher than 0.8 (see Table II), indicating that all the measurements are highly reliable. Measurement instrument Composite reliability CSR 0.934 GAJ 0.940 GP 0.962 GR 0.941 GRW 0.935 GS 0.976 GT 0.958 TMC 0.952 Notes: CSR, corporate social responsibility: GAJ, green job analysis and job description of job position; GP, green performance; GR, green recruitment; GRW, green rewards; GS, green selection; GT, green training; TMC, top management commitment Table II. Composite reliability of constructs Top management commitment 2065 Next, this study conducted statistical analysis on factor loadings, Cronbach's a and average variance extracted (AVE) to assess convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity refers to the extent to which a number of items measuring the same construct are highly related (Sekaran and Bougie, 2010). Based on the values depicted in Table III, the loading values and Cronbach's a for all items are higher than the threshold value of loading (0.7) and recommended Cronbach's a value (0.5), respectively. However, in terms of the AVE value, all items except for TMC and CSR are found to be established with high convergent reliability (AVE above 0.7). According to Hair et al. (2011), an AVE value of above 0.5 can also be accepted, which allows for the inclusion of the items in this particular study. Furthermore, the AVE values for all constructs are higher than 0.6, which indicates that the latent constructs can account for more than 60 per cent of the items' variance, proving that all items have convergent validity. The data is then analysed to assess its discriminant validity, which is indicated by comparing the AVE value of each construct with the square of its relation with any other construct. The purpose for assessing the discriminant validity is to ensure that there do not exist any two items within the same construct that are measuring the same thing, which would cause a redundancy in the data (Sekaran and Bougie, 2010). In order to establish discriminant validity, the value of AVE should be higher than the other constructs (Zait and Bertea, 2011), which, according to the values depicted in Table IV, is fulfilled here. Construct Variable Loading AVE Cronbach's a TMC 0.687 0.943 CSR 0.613 0.921 TMC1 TMC2 TMC3 TMC4 TMC5 TMC6 TMC7 TMC8 TMC9 CSR1 CSR2 CSR3 CSR4 CSR5 CSR6 CSR7 CSR8 CSR9 GHP1 GHP2 GHP3 GHP4 GHP5 GHP6 GHP7 GHP8 GHP9 GHP10 GHP11 GHP12 GHP13 GHP14 GHP15 0.790 0,856 0.804 0.851 0.861 0.867 0.759 0.816 0.849 0.729 0.788 0.727 0.734 0.806 0.775 0.863 0.813 0.798 0.874 0.943 0.931 0.953 0.933 0.976 0.977 0.933 0.954 0.934 0.931 0.960 0.947 0.922 0.952 GAJ 0.840 0.904 GR 0.889 0.877 GS 0.953 0.951 GT 0.885 0.935 GP 0.895 0.941 GRW 0.878 0.863 Table III. Convergent validity of constructs BIJ 26,6 2066 4.2 Hypothesis testing The structural model and hypotheses in Figure 2 were analysed to assess the acceptance or non-acceptance of the proposed hypotheses. The path, standard deviation, t-statistics and D-values are shown in Table V. In order for a hypothesis to be accepted, this study employs a one tailed t-statistic value. The hypothesis will be accepted if the t-value is higher than 1.65, and the p-value should be more than 0.5. The significance of each of the structural paths was calculated using the bootstrapping technique. This is indicated in Figure 3, where top management commitment is shown to have a significant positive effect on CSR (t-value: 2.689, p-value: 0.004). H3 is therefore supported. In terms of the relationship between top management commitment and the constructs of GHRM, all the items are found to have a highly positive effect: green analysis and description of job position (t-value: 4.747, p-value: 0.000), green recruitment (t-value: 3.650, p-value: 0.000), green selection (t-value: 4.413, p-value: 0.000), green training (t-value: 5.245, p-value: 0.000), green performance (t-value: 5.692, p-value:0.000) and green rewards (t-value, 5.443, p-value: 0.000). Hla, Hlb, Hlc, Hid, Hle and Hif are therefore supported. TMC CSR GAJ GP GR GRW GS GT TMC CSR GAJ GP GR GRW GS GT 0.829 0.287 0.512 0.469 0.391 0.534 0.432 0.480 0.783 0.363 0.222 0.277 0.246 0.174 0.275 0.917 0,635 0.664 0.553 0.601 0.704 Table IV. Fornell-Larcker criterion 0.946 0.673 0.815 0.774 0.780 0.943 0.642 0.858 0.656 0.937 0.699 0.748 0.976 0.713 0.941 Green Human Resource Management H1 Top Management Commitment Green Analysis and Job Description of Job Position H1b H11 HIC H3 Green Performance H2a/H2D Hid Green Recruitment Corporate Social Responsibility H2 H2d Hie H2e H21 Green Rewards Green Selection Figure 2. Proposed structural model and hypotheses Green Training Path coefficient SD t-statistic p-values 4.747 Hypothesis Hla TM - GAJ Hib TM - GP Hic TM - GR Hid TM - GRW Hle TM - GS Hif TM GT H2a CSR - GAJ H2b CSR - GP H2C CSR GR H2d CSR GRW H2e CSR - GS H21 CSR GT H3 TM - CSR 0.444 0.442 0.339 0.505 0.416 0.437 0.236 0.095 0.180 0.101 0.054 0.150 0.287 0.094 0.078 0.093 0.093 0.094 0.083 0.117 0.110 0.116 0.102 0.121 0.110 0.107 5.692 3.650 5,443 4.413 5.245 2.016 0.869 1.547 0.993 0.447 1.367 2.689 0.000 0.000 0.000 0,000 0.000 0.000 0,022 0.193 0.061 0.161 0.327 0.086 0.004 Top Result management Supported commitment Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported 2067 Supported Not supported Not supported Not supported Not supported Table V. Not supported Results of hypothesis Supported testing GHP1 TMC1 0.874 GHP2 -0.943 0.313 TMC2 0.931 GHP3 GAJ 0.444 0.182 0,953 GHP4 -0.339 0.933 TMC3 0.790 0.856 TMC4 0.804 0.851 TMC5 -0.861 0.867 TMC6 0.759 GTM 0.816 TMC7 0.849 GR GHP5 0.416 GHP6 0.976 0.189 0.977 GHP7 TMCB 0.437 GS TMC9 GHP 10 0.236 0.442 0.180 0.287 0.251 0.505 0.054 0.934 0.933GHP8 0.954 GHP9 CSR1 GT GHP11 0.150 0.931 0.228 0.960 GHP12 0.947 0.095 GP GHP13 CSR2 CSR3 0.729 CSR4 0.788 0.727 CSR5 0.734 0.806 0.082 -0.775 CSRB 0.863 CSR CSR7 0.813 0.798 CSRB 0.101 0.295 GHP14 0.922 0.952 GHP15 GRW Figure 3. PLS results of the proposed model CSRS 17/29 In terms of the relationship between CSR and GHRM, only one dimension gret. analysis and description of job position - is supported (t-value: 2.016, p-value: 0.022). H2a is thus supported. The other dimensions of GHRM: green recruitment (t-value: 1.547, p-value: 0.061), green selection (t-value: 0.447, p-value: 0.327), green training BIJ 26,6 (t-value: 1.367, p-value: 0.086), green performance (t-value: 0.869, p-value: 0.193) and green rewards (t-value: 0.993, p-value: 0.161) were all found to be insignificant, thus rejecting hypotheses H21, H2c, H2, H2e and H2f. 2068 5. Discussion and conclusion The originality of this research is in putting together the relationship between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM. Based on the best knowledge of the authors, this is the first work testing this theoretical framework in light of empirical evidence from Malaysia, contributing to a better understanding of sustainability in manufacturing and service companies, which remains a gap in the state-of-the-art literature (Gunasekaran and Spalanzani, 2012). This section focuses on the main findings of the study, giving prominence to the following: the research objectives; implications; limitations of the research and future research directions. 5.1 Research objectives This paper proposed a framework for evaluating the greening of HRM practices in manufacturing and service organisations. The authors conducted this research from the perspective of 87 organisations in Malaysia. The aim of this study was to examine top management commitment and CSR, and whether these have a positively significant influence on GHRM. The study has also proposed that top management commitment has a positive, significant influence on CSR. 5.2 Main findings The observed findings indicate a significant positive relationship between top management commitment and CSR. Besides, top management commitment is found to have a significant positive effect on all dimensions of GHRM practices (green analysis and description of job position, green recruitment, green selection, green training, green performance and green rewards). However, counterintuitively, the relationship between CSR and GHRM was found not to be as significant as expected (except for CSR and green analysis and description of job position) 5.3 Theoretical implications We set out to explore the relationship between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM. First, our research provided empirical evidence for positive relationships between top management commitment and all dimensions of GHRM. This result suggests that the higher top management commitment is, the higher the chances of GHRM being practiced as the HR strategy of an organisation. As previously shown, this can be explained because any goal in an organisation is dependent on the commitment of top management (Williams et al., 2014); top management can convince and disseminate practices with an environmental approach at all organisational levels, including GHRM practices (Paill et al., 2014). This supports extant research showing positive links between top management commitment and corporate environmental practices (Lee and Ball, 2003) and environmental sustainability (Colwell and Joshi, 2013). However, these studies do not focus on GHRM. This result indicates the crucial importance of top management commitment in supporting companies' initiatives towards implementing GHRM practices within the organisation. As explained by Williams et al. (2014), the success of any goal in an organisation is dependent on the commitment of top management, and the case analysed in this paper is no different. Top management support is the key driver of GHRM implementation and decision making to decide on the strategic Top management commitment 2069 direction and assessment of the company. In general, a green, or sustainable, HRM approach is part of a broad HRM strategy (Kramar, 2014), and a strategy with a top-down characteristic and top management commitment is a key element in disseminating the strategy across all organisational levels. Some internal environmental orientations come from the personal commitment of top management (Paill et al., 2014). Thus, a manager is an important source of inspiration and motivation to other employees becoming more environmentally conscious, and top management has an important role to play in convincing and disseminating HRM practices with an environmental approach at all organisational levels (Paill et al., 2014). To improve business outcomes, top management needs to specifically design strategic plans for talent management, especially on job descriptions. GHRM will be successfully implemented if the top management supports green innovative performance assessment, recruitment, rewards, selection and training. Amongst other domains of GHRM, green reward has the highest the path coefficient value, which indicates that this is a critical aspect of implementation. Besides, Daily and Huang (2001) argue that top management within an environmentally conscious organisation should strive for a strong culture that allows its employees the freedom to make environmental improvements. Second, our study extends the literature on the role of CSR in GHRM practices. Our result shows that CSR is positively related to only one dimension of GHRM practices (i.e. green analysis and description of job position). Our results support the hypothesis that the higher the level of CSR practices within an organisation, the higher their green analysis and description of job position is. Some studies have shown a certain relationship between CSR and HRM (Jamali et al., 2015; Shen and Benson, 2016; Voegtlin and Greenwood's, 2016). Jamali et al. (2015) established a CSR-HRM co-creation model, which is believed to create a beneficial outcome from such synergy. Ideally, CSR implementation can improve employee morale and proved the basis to practice GHRM in firms. Those employees who have a better view and idea of how well firms can implement better CSR programme should be appreciated more. Novel ideas and creativity in CSR implementation should be in line with green analysis and description of job position. Voegtlin and Greenwood (2016) have argued that CSR and HRM can be seen as relevant in understanding the assumptions concerning the role of the corporation and the relationship between employer and workers, and have called for a comprehensive examination of the relationship between these two constructs. This is an important finding, given that Voegtlin and Greenwood's (2016) study has proposed how this relationship should be linked. Third, our results also found that the role of top management commitment is positively related to CSR. The present study also contributes to the literature on the relationship between top management commitment and CSR. The findings show that the higher the commitment given by top management, the greater the contribution by the corporation to CSR activities. This finding supports the argument that, in order for CSR to work in a company, it must have an internal champion; top-level management commitment is crucial to its success (Jenkins, 2009). Furthermore, in a large company, top-tier managers may support CSR, but it is usually driven by champions at the middle tier working in departments such as human resources or external relations (Jenkins, 2009). Fourth, through these findings, our research can make various contributions to the GHRM literature in general and the sustainable HRM literature in particular. Prior studies in GHRM have focused on environmental aspects (O'Donohue and Torugsa, 2016; Rangarajan and Rahm, 2011; Zibarras and Coan, 2015), green supply chain management (SCM) (Longoni et al, 2016; Nejati et al., 2017; Teixeira et al., 2016), CSR (Jabbour, 2011; Wagner, 2013), stakeholder pressure (Guerci, Longoni and Luzzini, 2016), resistance to change (Nejati et al., 2017), strategic HR competencies (Yong and Mohd-Yusoff, 2016), HR factors (Yusliza et al., 2017), performance (Guerci, Longoni and Luzzini, 2016; Longoni et al., 2016; BIJ 26,6 2070 Masri and Jaaron, 2017; O'Donohue and Torugsa, 2016; Siyambalapitiya et al., 2018; Yusoff et al., 2018) and competitive advantage (Carmona-Moreno et al., 2012). Our research focuses on top management commitment, CSR and GHRM, thereby filling the gap represented by the dearth of research on GHRM in the sustainable HRM literature. Based on these results, organisations therefore need to focus more attention on top management commitment, as it does help companies to be more involved in CSR activities and GHRM practices. Finally, our study investigates the relationship between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM practices, focusing on emerging countries and, in particular, on the Malaysian context. Our study is therefore in line with the recommendation of Renwick et al. (2013) to further study green and environmental HRM in developing Asian countries. Therefore, to our knowledge, this is the first attempt to empirically test the link between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM practices. Furthermore, our study is perhaps the first attempt to develop this kind of research framework, extending the organisational behaviour and HRM literature in relation to environmental studies. 5.4 Practical implications Our research provides practical contributions to HR managers and top management in a number of ways. First, organisations should take the initiative in creating an enabling environment for CSR, and this must start from the top management, who should be committed to helping organisations in satisfying their CSR objectives. The commitment of top management towards CSR is very important, and should be expressed in tangible terms to reinforce the right kind of behaviour in the organisation. CSR activities should be promoted and supported by top management in order to develop a sense of ownership amongst the employees and to create a basis for the continuation of the CSR activities themselves (Morsing et al., 2008). For example, organisations should inculcate CSR values amongst its new recruits right at the beginning, during the induction process. Furthermore, departmental updates through emails, regular newsletters and presentations are mechanisms which can be used to keep employees aware of the organisation's socially responsible initiatives. Second, managers have to take into consideration the importance of commitment from top management in supporting GHRM practices within the organisation. Top management should pay more attention to linking their commitment with GHRM practices to achieve environmental initiatives introduced by the organisation. Managers should be mindful that adopting GHRM practices will be successful if commitment from the top management is guaranteed as one of the strategies to achieve low carbon organisational success. Thus, managers should determine clear definitions for GHRM. They should allocate more funds for training key employees involved in GHRM practices to ensure effective implementation. Third, managers need to focus on green analysis and description of job position, aimed at aligning GHRM strategies with CSR strategy and ways to successfully execute these strategies. Top management must set volunteering activities as part of employees' job analysis and job description, and create systems of recognition for volunteering work done as part of GHRM practices. Volunteers will continue if these activities are part of their involvement and knowledge about environmental management in their analysis and description of job position. 5.5 Limitations of this research Although our findings are robust and important, they do have some limitations that need to be explicitly acknowledged. The limitations of this study may be associated with the proposed framework and its application. First, although the variables selected for the framework can be considered adequate for studies on GHRM practices in organisations, it is believed that other variables can also contribute to this framework. Furthermore, the framework must be further refined and adjusted by being adapted to include other organisations and other countries to conduct a cross-country study, which may enhance the generalisability of the findings, and may affect the results. Moreover, the data collection phase in this study occurred at one point of time. Finally, we have used subjective measurements (self-assessment) in our questionnaire, although these were adopted from previous studies. Top management commitment 2071 5.6 Future research directions Notwithstanding the limitations of our research, this study may be extended to include other GHRM practices and to empirically investigate how each GHRM practice can complement others in different conditions. It should be recognised that GHRM practices should be evaluated in terms of having different dimensions, either at the individual or organisational level of study. Additionally, our study may be enhanced by using samples from other industries and firm sizes, using longitudinal data to establish causal relationships amongst independent and dependent variables, or using multiple cases to further investigate the role of top management commitment, CSR and GHRM practices. The possible association amongst the triple bottom line of sustainability can further be explored, as well as the inclusion of constructs such as environmental knowledge and awareness, environmental concern, HR roles and competencies, stakeholder pressure and green intellectual capital. Finally, given temporary conditions as well as considering environmental aspects in the management of the organisation, future frameworks could be explored by focusing on environmental performance as their ultimate goal. We hope that this study will offer an alternative lens to those who study the impact of top management commitment and CSR on GHRM practices. Report should contain the following sections: (1) Introduction; (2) Literature Review: (3) Research Aims and Objectives: (4) Research Methodology: (5) Discussion; (6) How the qualitative approach could be used to address the research problem (7) paper critique; (8) Conclusion: (9) References Top management commitment Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and green human resource management A Malaysian study 2051 Received 17 September 2018 Revised 22 January 2019 Accepted 5 February 2019 M.-Y. Yusliza School of Maritime Business and Management, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia Nurul Aimi Norazmi Maxshift Sdn. Bhd., Prai, Malaysia Charbel Jos Chiappetta Jabbour Montpellier Business School, Montpellier, France Yudi Fernando Faculty of Industrial Management, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Kuantan, Malaysia Olawole Fawehinmi School of Maritime Business and Management, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, and Bruno Michel Roman Pais Seles Department of Production Engineering, Sao Paulo State University (UNESP), So Paulo, Brazil Abstract Purpose - The purpose of this paper is to analyse the relationship between top management commitment, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and green human resource management (GHRM). Design/methodology/approach - A self-administered questionnaire was adopted to perform a systematic collection of data from manufacturing and service organisations in Malaysia. The partial least squares method was used for the conceptual framework of the study. Findings - The observed findings indicate a significant positive relationship between top management commitment and CSR, as well all dimensions of GHRM. However, counterintuitively, the relationship between CSR and GHRM was found not to be as significant as expected (except for CSR and green analysis/job description), which can be explained through the emerging perspective that CSR and HRM should be linked. Research limitations/implications - The findings provide insights as to the nature of GHRM and how it is affected by CSR and top management commitment in an emerging economy in this particular study, Malaysia. Moreover, the observed results highlight the crucial importance of top management commitment in implementing GHRM practices and CSR efficiently in order to create positive environmental performance. Originality/value The authors believe that, to date, no study has explored the links between top management commitment, CSR and GHRM using empirical data from Malaysia, as well as that this research is an important emerging topic for researchers, academicians and practitioners. Keywords Sustainability, Corporate social responsibility, Emerging economy, Top management commitment, Green human resource management Paper type Research paper Benchmarking: An International Journal Vol. 26 No. 6, 2019 pp. 2051-2078 Emerald Publishing Limited 1463-5771 DOI 10.1108/BIJ-09-2018-0283 This study was funded by Exploratory Research Grant Scheme from Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (Grant No. 203/PPAMC/6730125). BIJ 26,6 2052 1. Introduction Managing corporate environmental sustainability is a complex task, and can be considered one of the major challenges faced by organisations (Dubey et al., 2015). It has become imperative for any organisation not only to act responsibly towards the environment, but also to behave in a socially responsible manner while trying to achieve its economic goals (Gupta et al., 2018). In order to achieve proactive corporate environmental sustainability, organisations must mobilise their human resources in pursuing green objectives (Daily and Huang, 2001), thus linking environmental sustainability to the future of human resource management (HRM) (Jackson et al., 2014). Therefore, there exists a growing need for businesses to integrate environmental management into their HRM practices (Longoni et al., 2016; Jabbour and Santos, 2008; Paill et al., 2014; Renwick et al., 2008, 2013, 2015; Wagner, 2011, 2013). In response to these concerns, the concept of green human resource management (GHRM) has been devised (Ahmad, 2015; Gholami et al., 2016; Haddock-Millar et al., 2016; Jabbour, 2011; Jabbour and Jabbour, 2016; Jackson et al., 2011; Renwick et al., 2013, 2015; Yong and Mohd- Yusoff, 2016; Yusliza et al., 2017) as an answer to the crucial need for the expansion of the role of HRM in the pursuit of environmentally sustainable business practices. The term "green", added to the traditional idea of HRM, may include activities and practices that involve the preservation and conservation of the natural environment, avoidance or minimisation of environmental pollution and the generation of gardens and natural places (Jackson et al, 2011). In addition, the adoption of a management system focused on environmental sustainability is also believed to provide a competitive advantage for companies (Yang Spencer et al., 2013). In fact, studies have shown that GHRM practices affect voluntary behaviours towards the environment (Pinzone et al., 2016), implementation of environmental management systems (Jabbour et al., 2010; Wagner, 2013), environmental performance (Guerci, Longoni and Luzzini, 2016), green supply chain management (Jabbour and Jabbour, 2016; Longoni et al., 2016) and employees' green behaviour, both in-role and extra-role (Dumont et al., 2016). There are two main reasons that top management support is needed to practice corporate social responsibility (CSR) and GHRM in the context of emerging economies. First, the emerging world has received direct foreign investment to set up new manufacturing plants and create job opportunities. Some countries in the Asian region have contributed to sustainable development programmes, and most of these countries are categorised as emerging economies. Many manufacturing plants are now concentrated in the region, and green practices are attracting scholars' attention (Fernando et al., 2016). The industry should not consider revenue alone as the main indicator of business success, but perhaps more importantly need to ensure that the company employs sustainable and responsible business practices and activities for the wellbeing of stakeholders. Second, top managStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

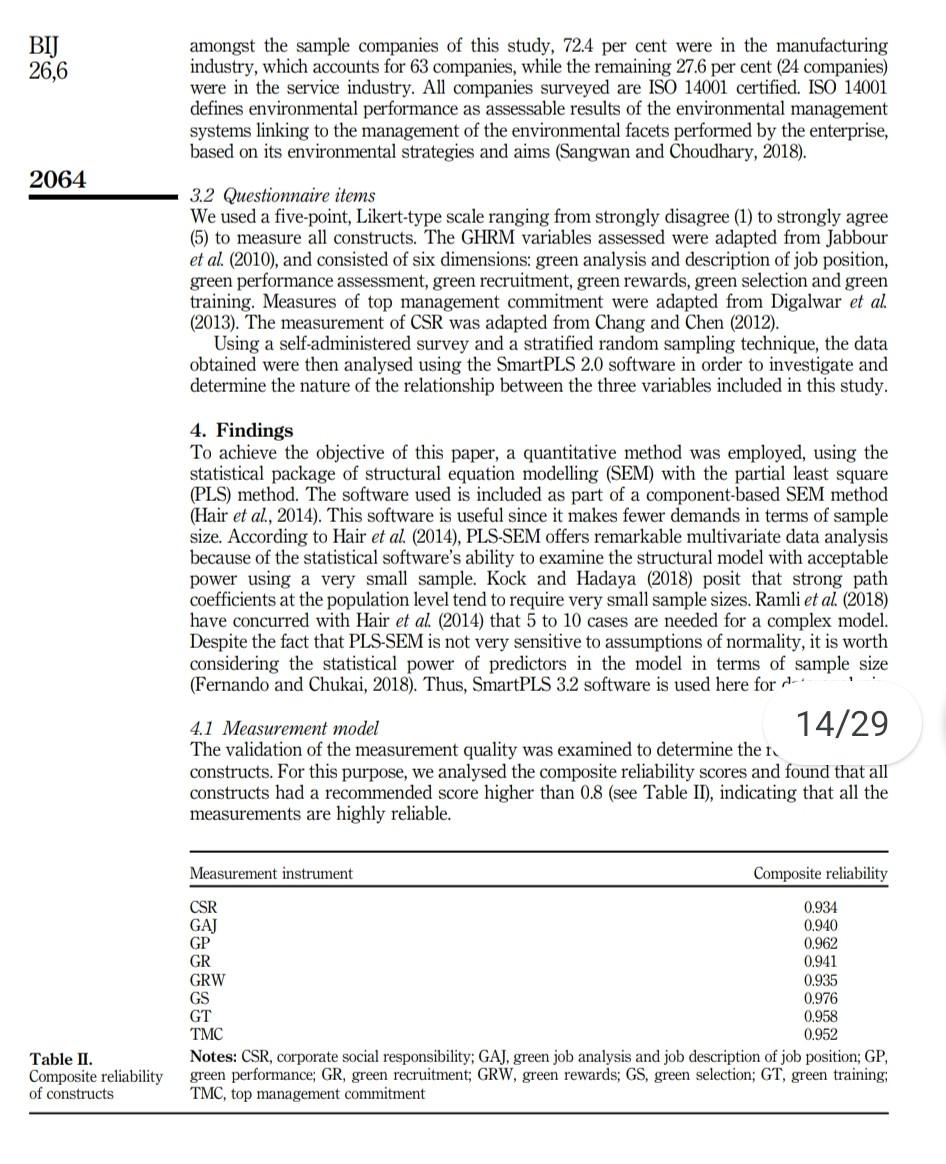

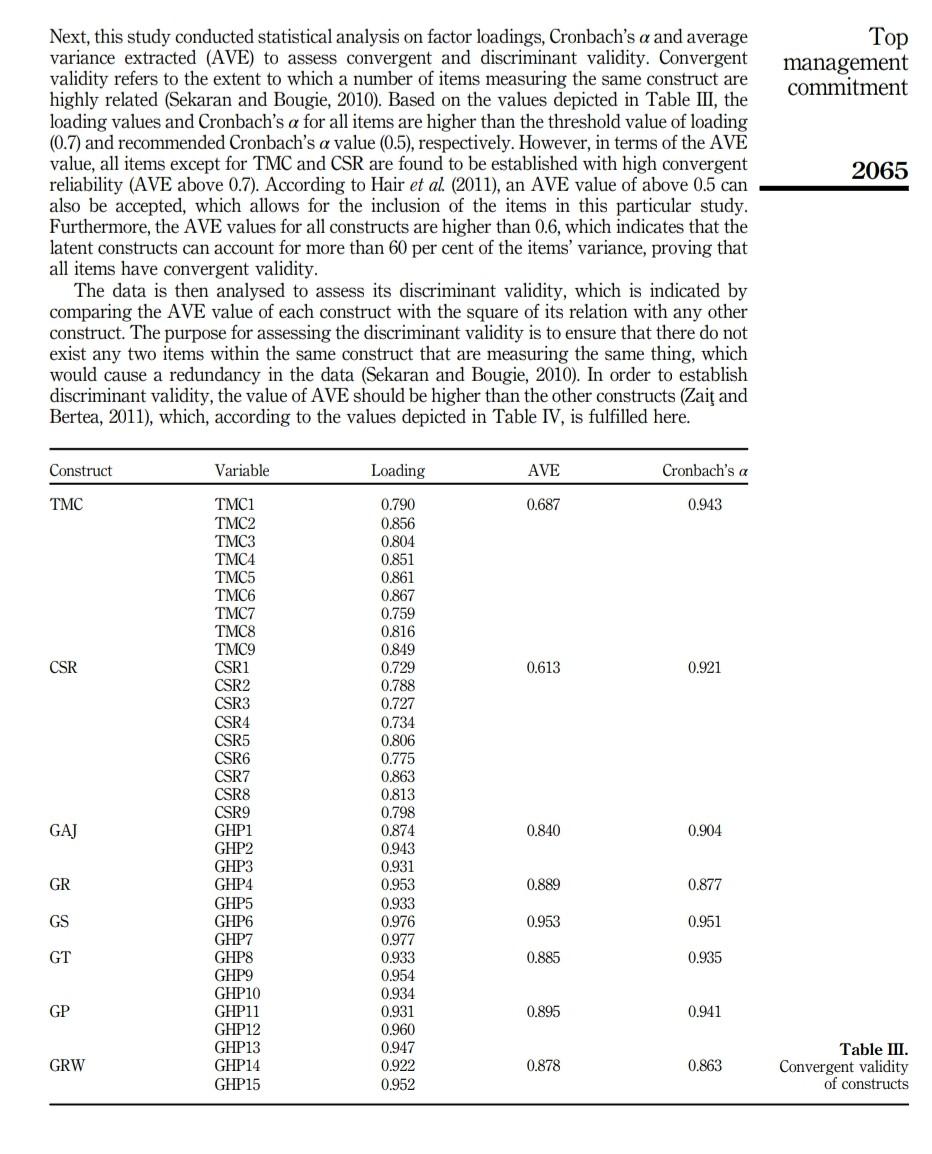

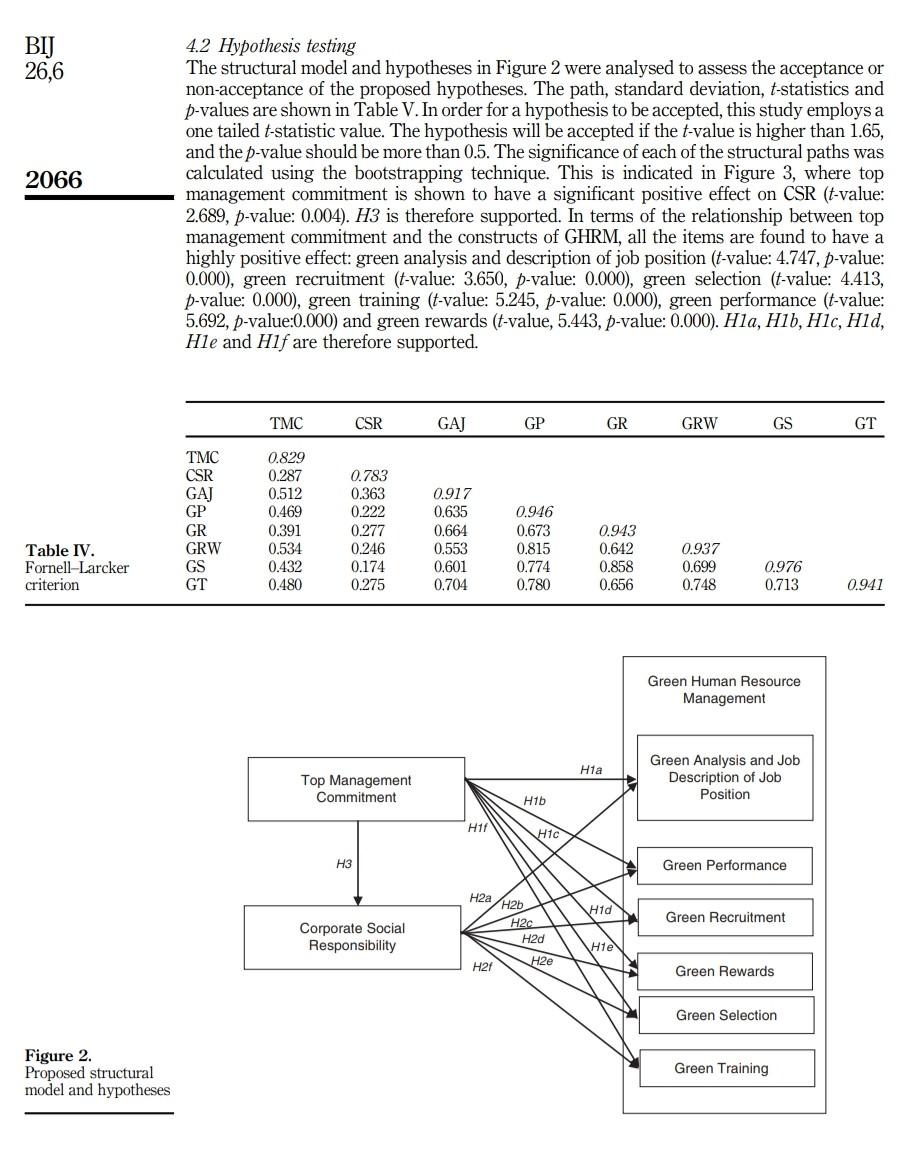

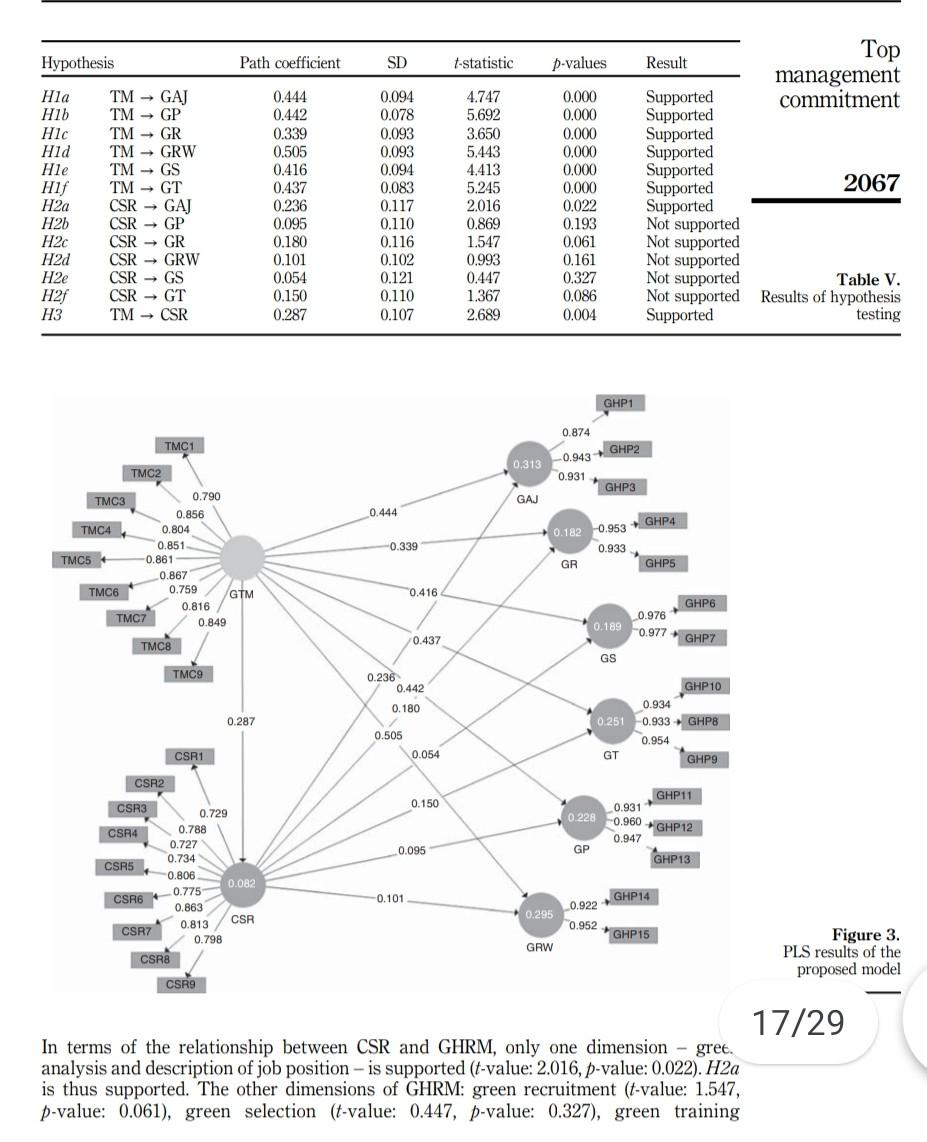

Step: 3 Unlock