Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Requirements 1. The report is at least five pages long, and please follow APA formatting. 2. Include your name, section, and student ID on the

Requirements

Requirements

1. The report is at least five pages long, and please follow APA formatting.

2. Include your name, section, and student ID on the title page.

3. In the report, you should include the case synopsis (a brief summary of the case background and key issues), which is between half to one page (5 points).

4. In the report, you should answer the following questions (Note: Questions not answered are taken as zero):

- Why do customers patronize Wal-Mart's China stores? What does sustainability mean to them, and how important is it?

- How should sustainability be incorporated in vendor selection and evaluation? How could vendors be encouraged to participate in Wal-Mart Chinas sustainability initiatives?

- What are the distinguishing features of Wal-Mart Chinas distribution system? How does it achieve relatively high availability with similar stock levels (weeks cover) to other companies?

- How can Wal-Mart improve sustainability in its distribution and retail operations (consider reduce, reuse and recycle, as well as innovation)?

- How should Wal-Mart China relate to the government and employees in advancing sustainability?

- 5. This report has to be original for each individual, i.e., any form of plagiarism (use of online published answers or similar answers with other teams) will be recorded, and a penalty will be enforced.

- .

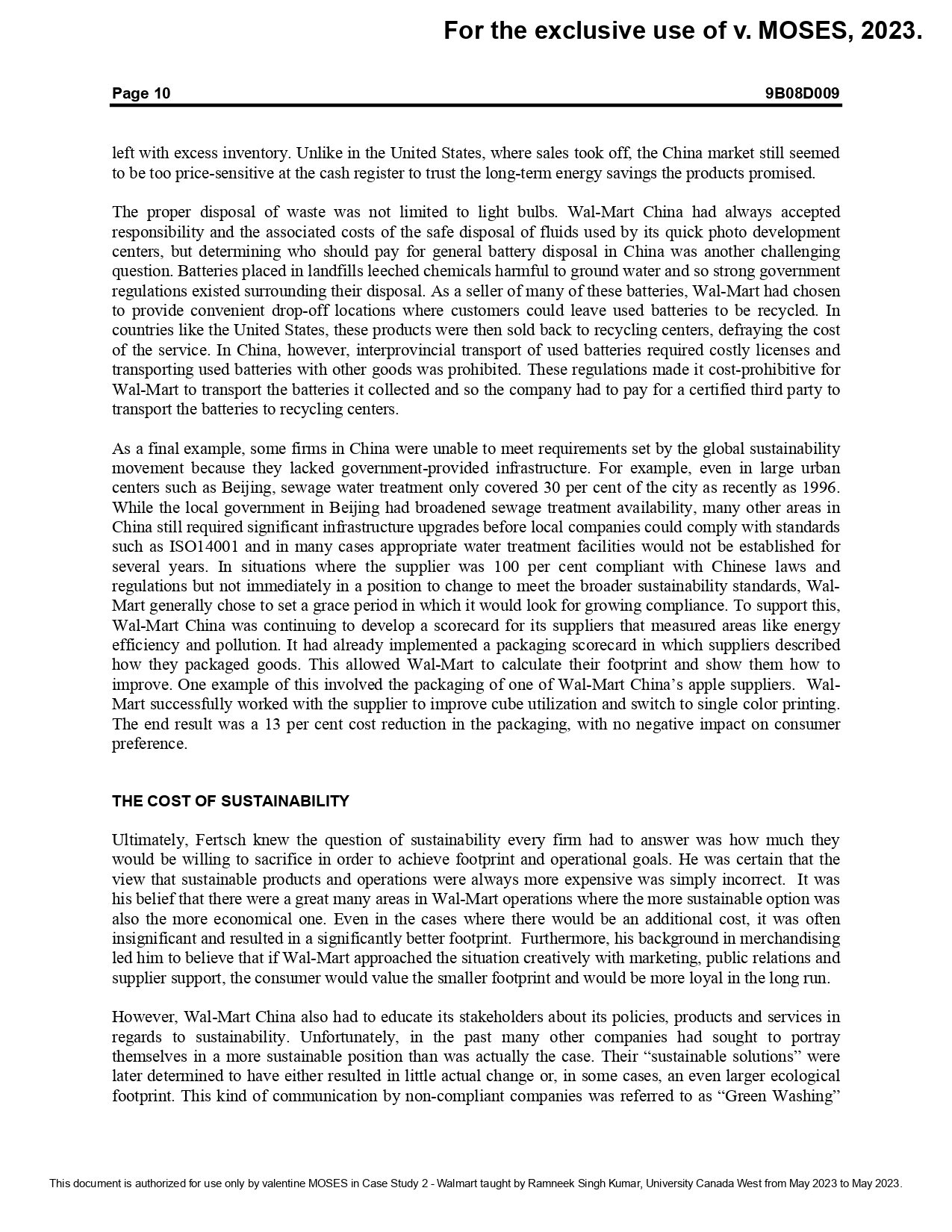

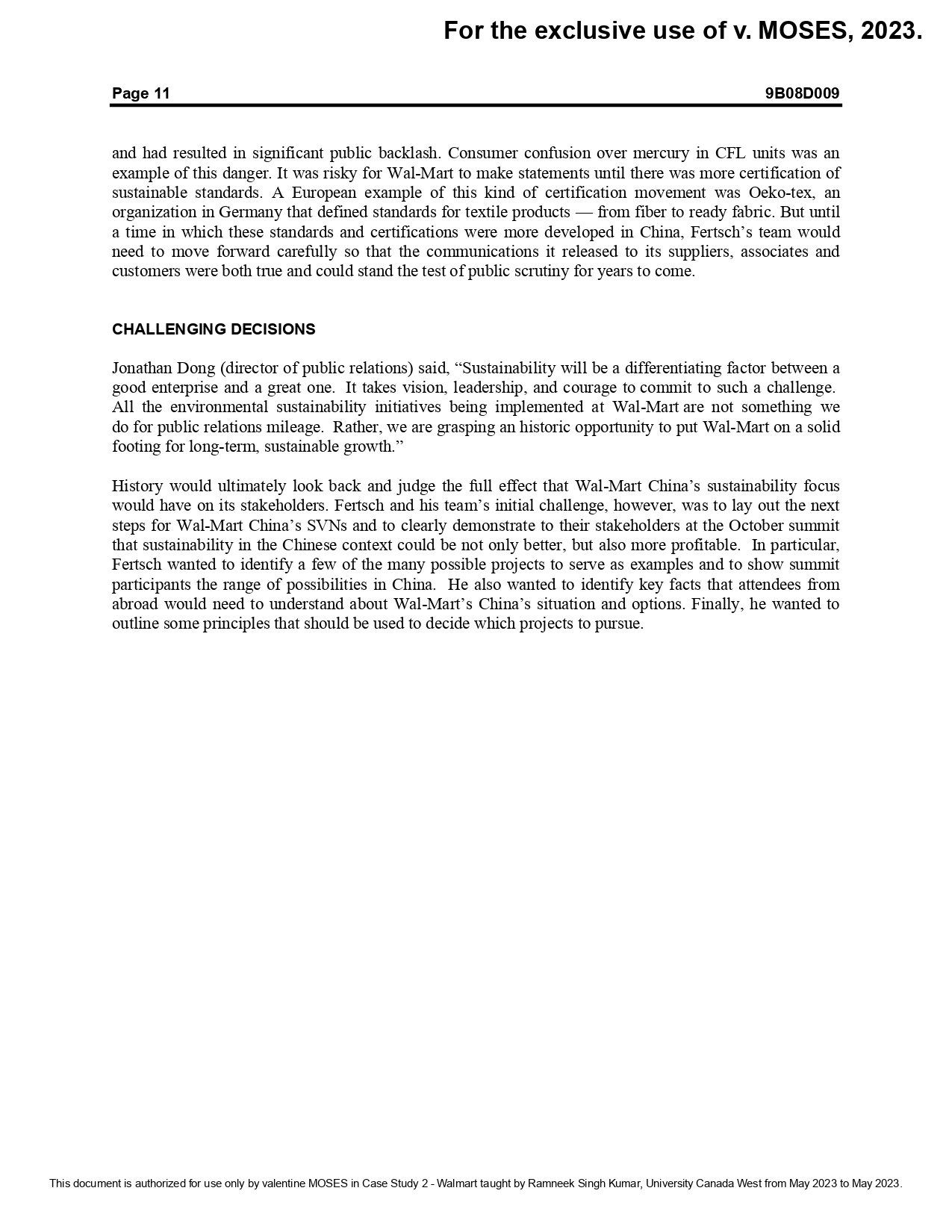

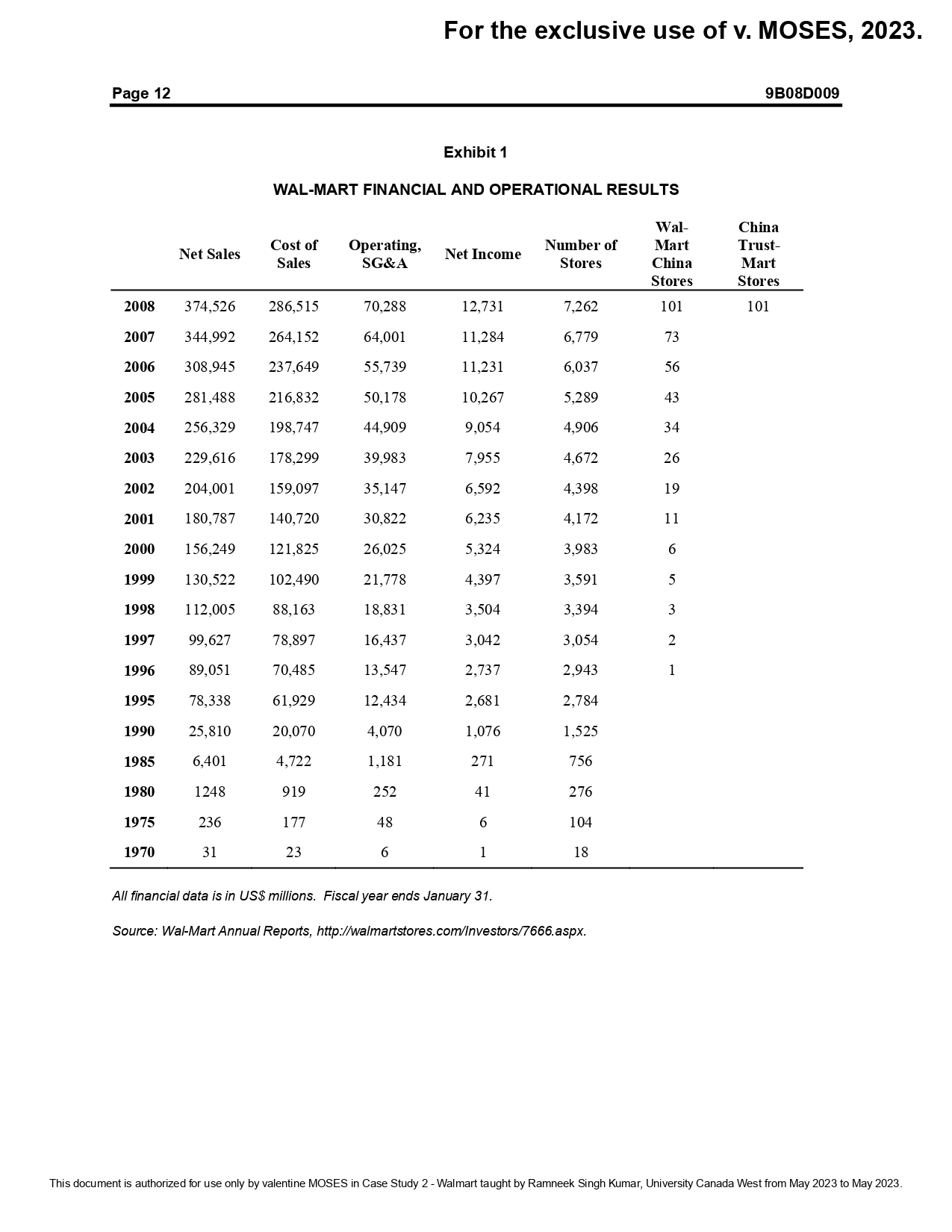

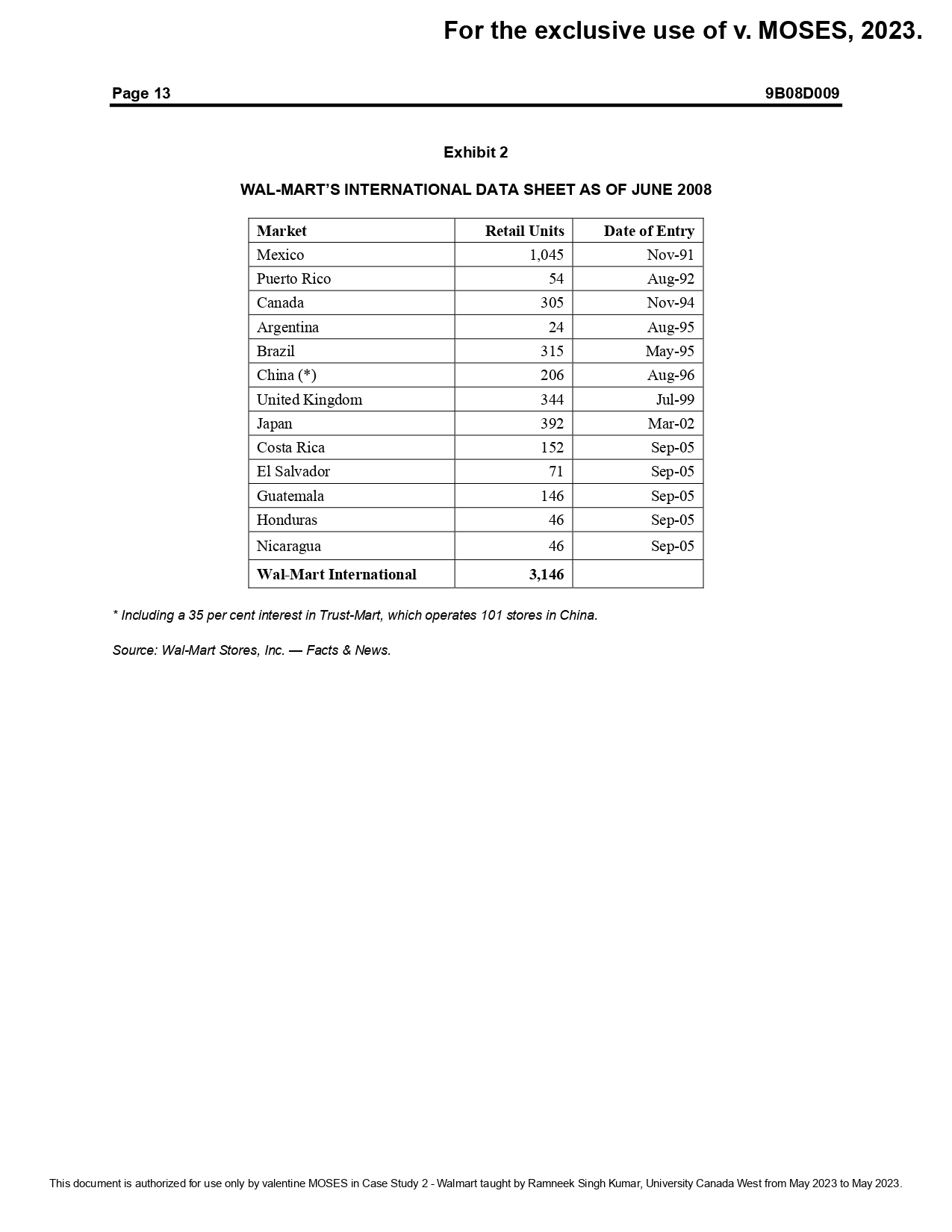

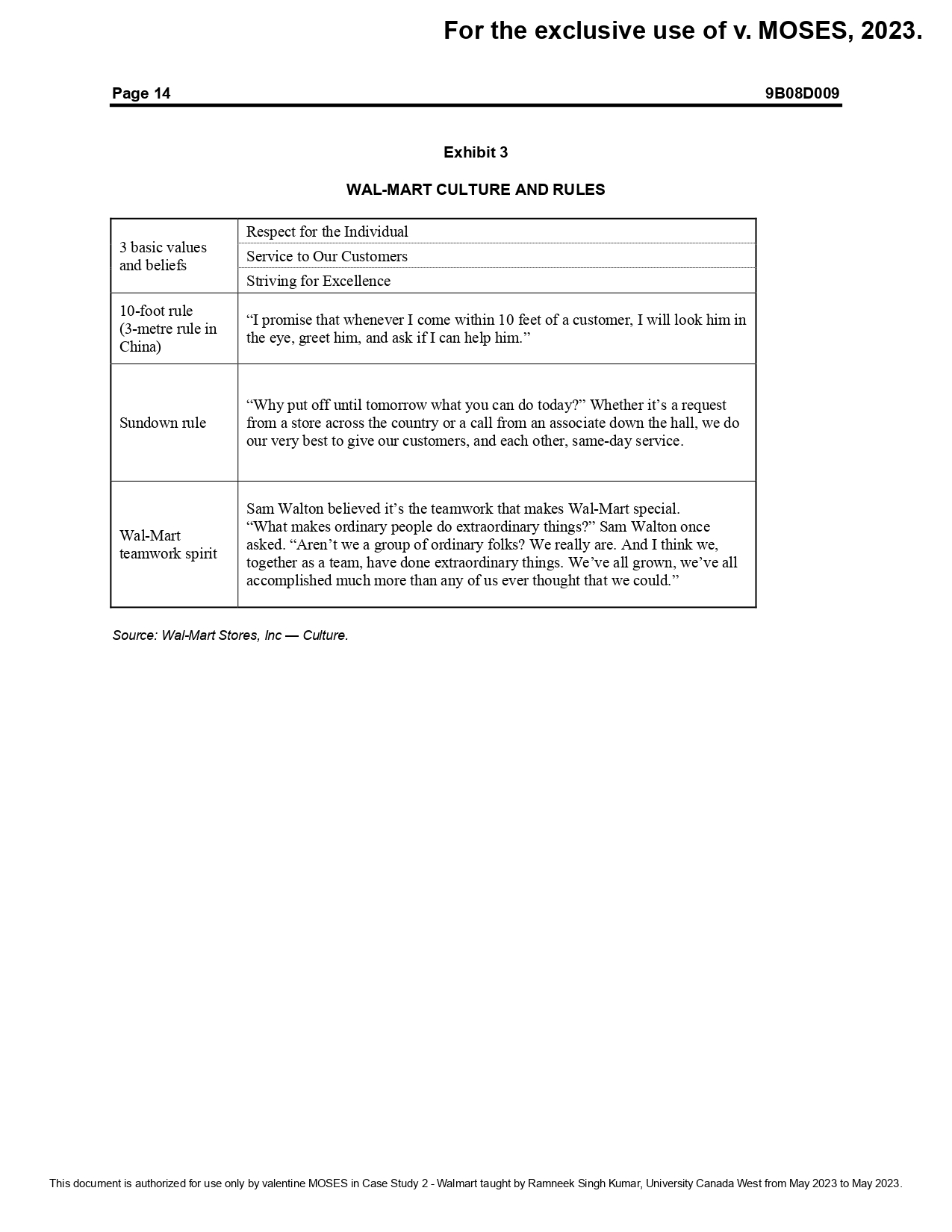

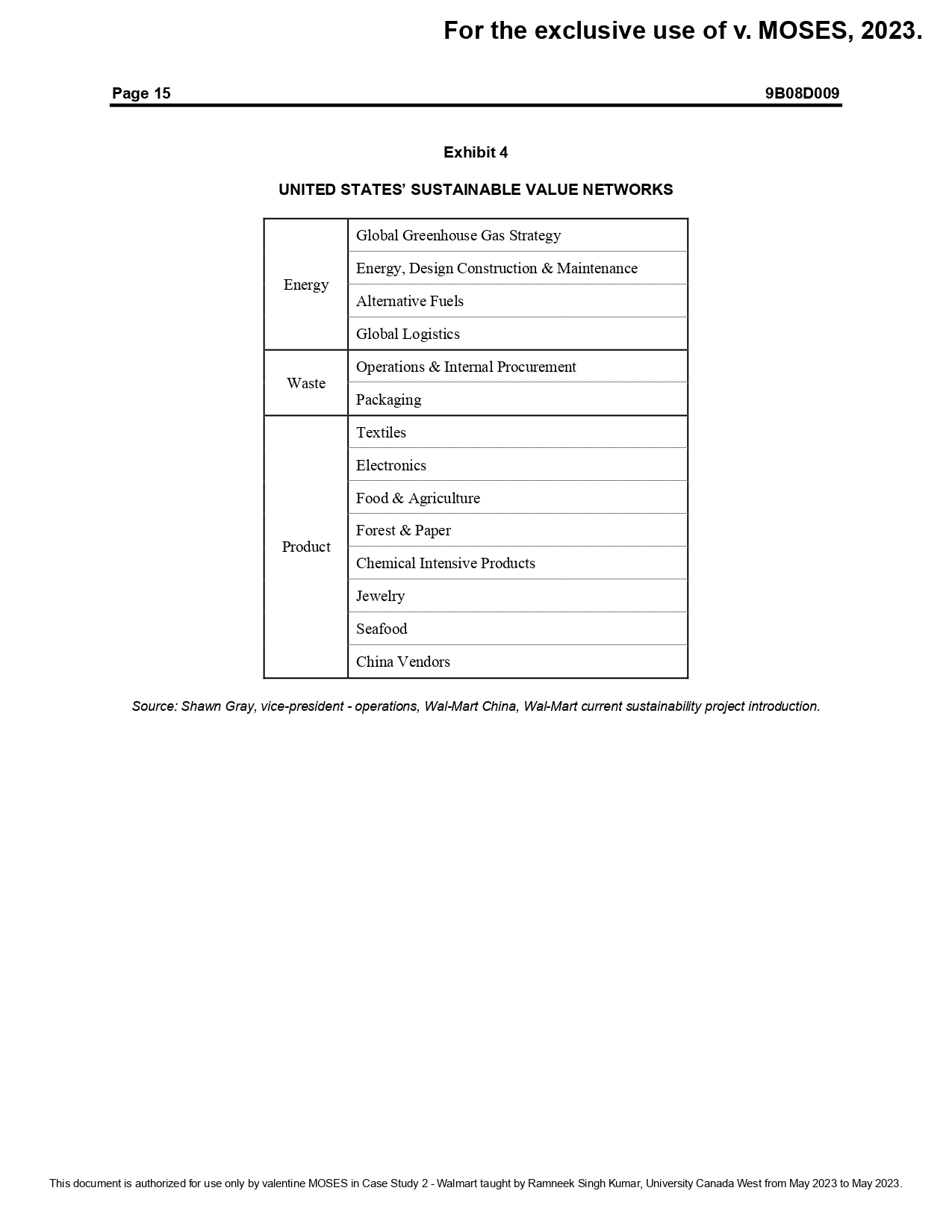

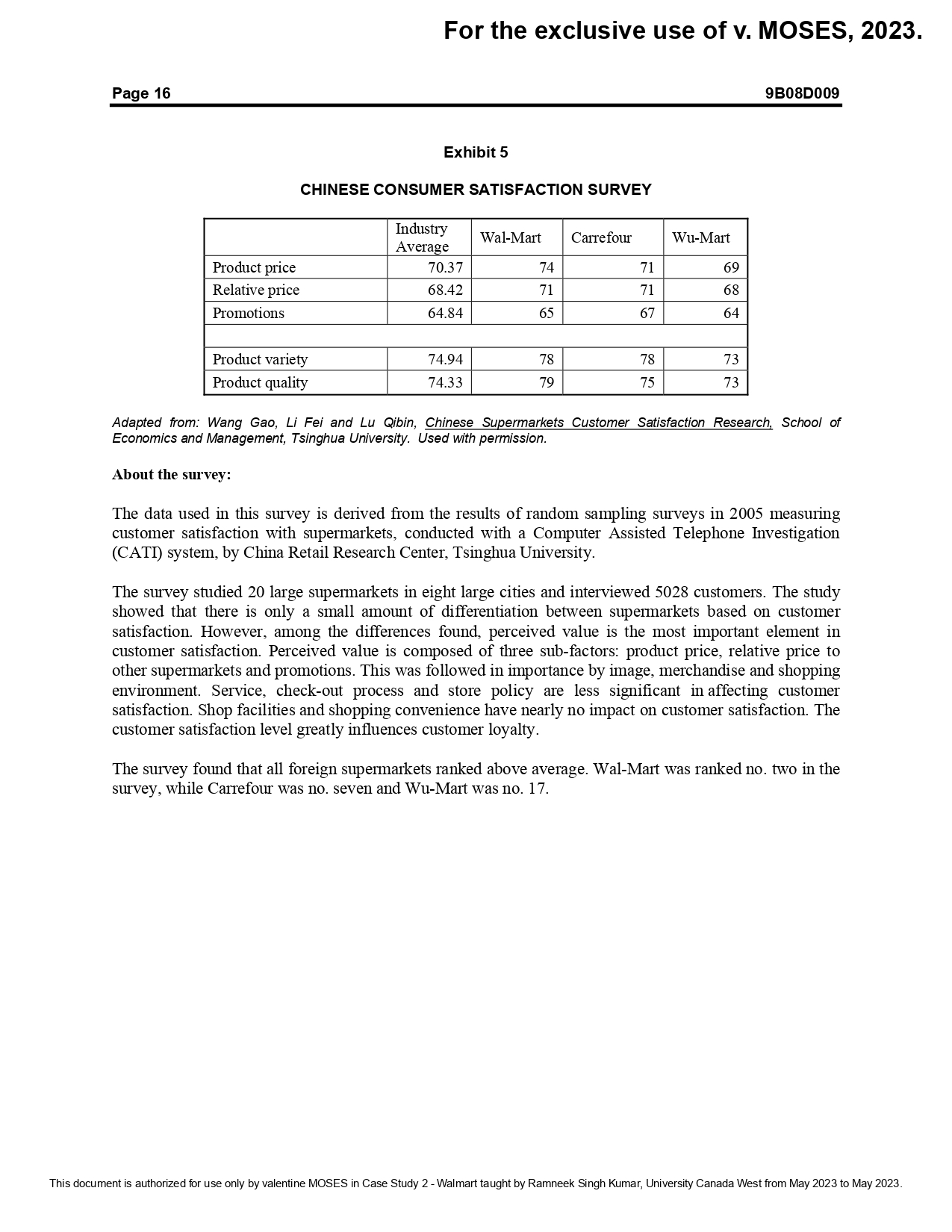

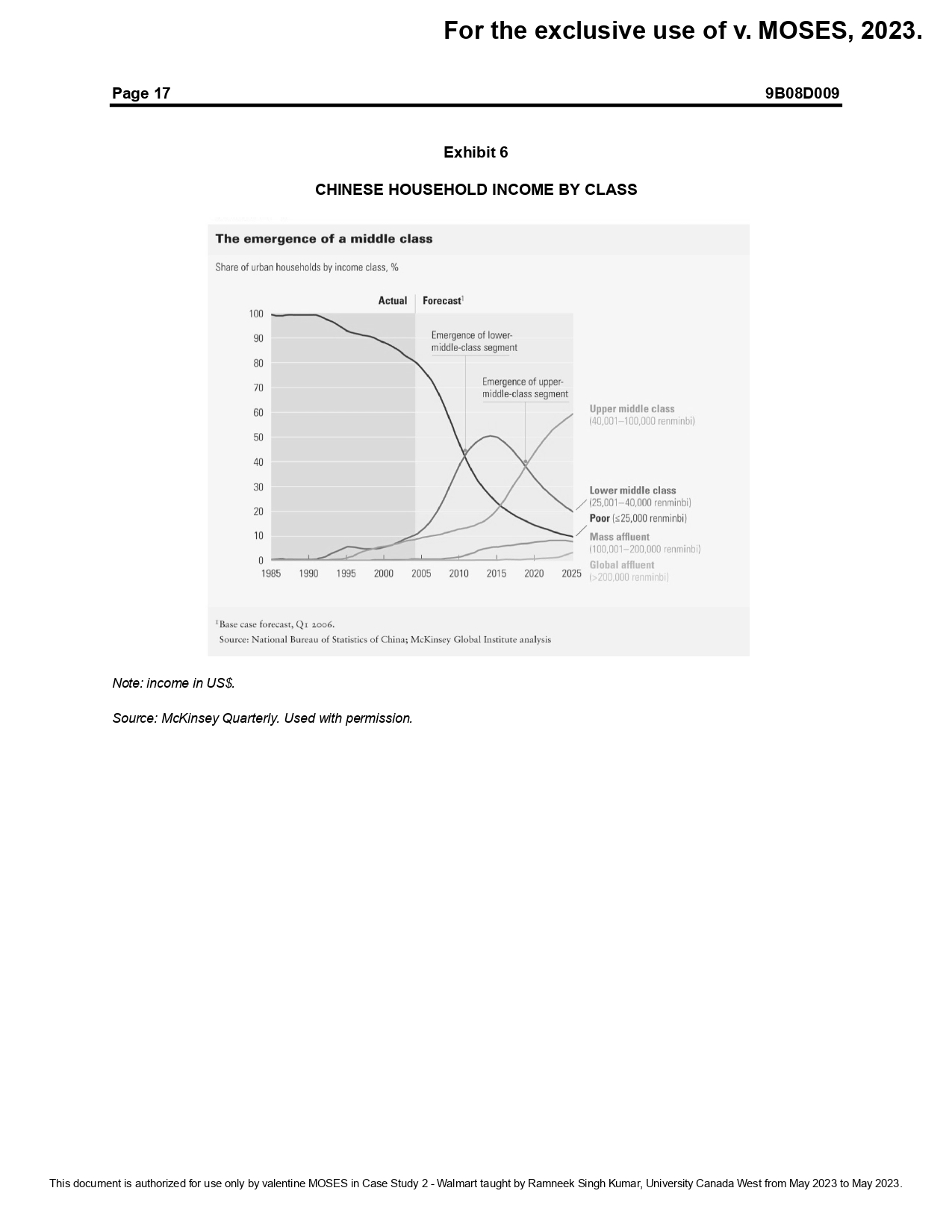

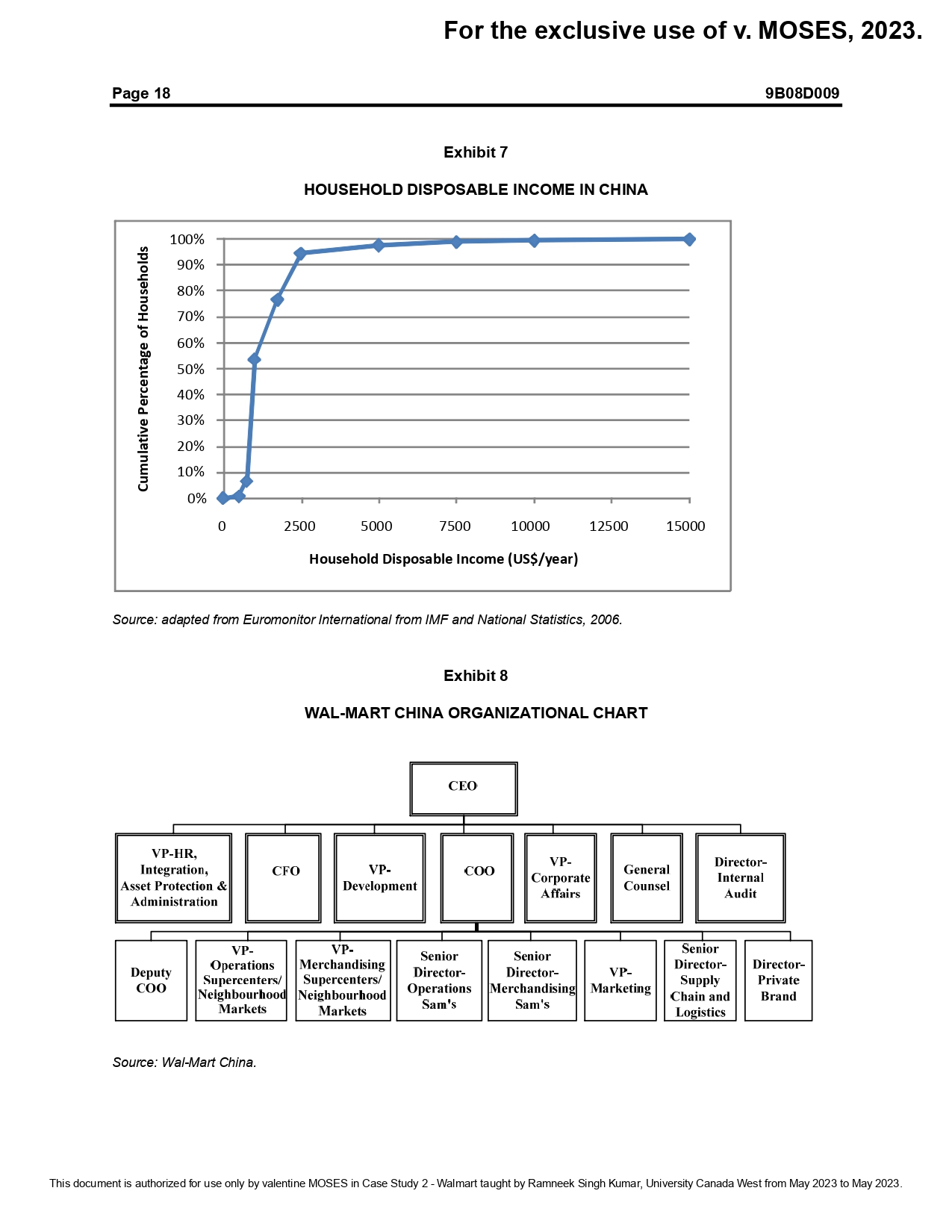

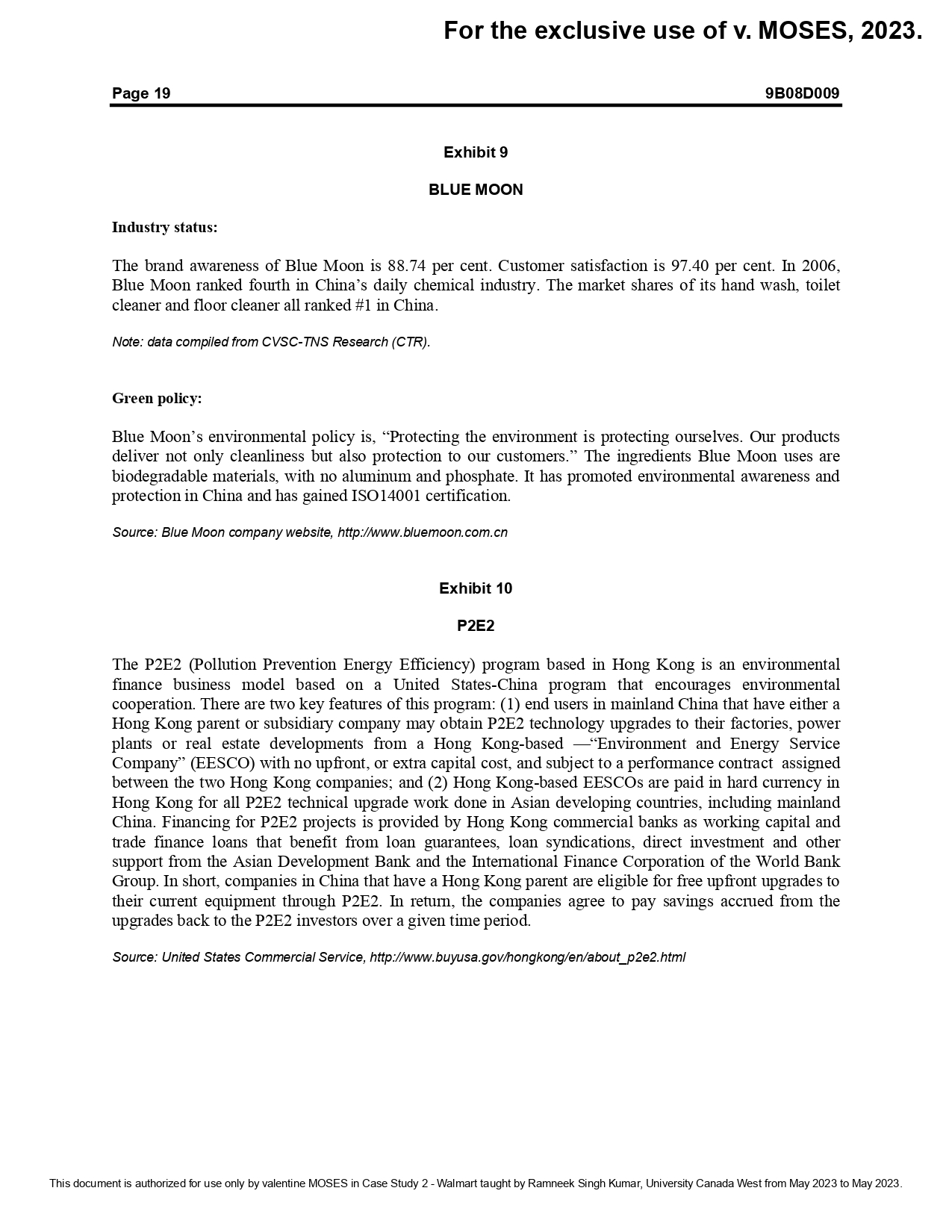

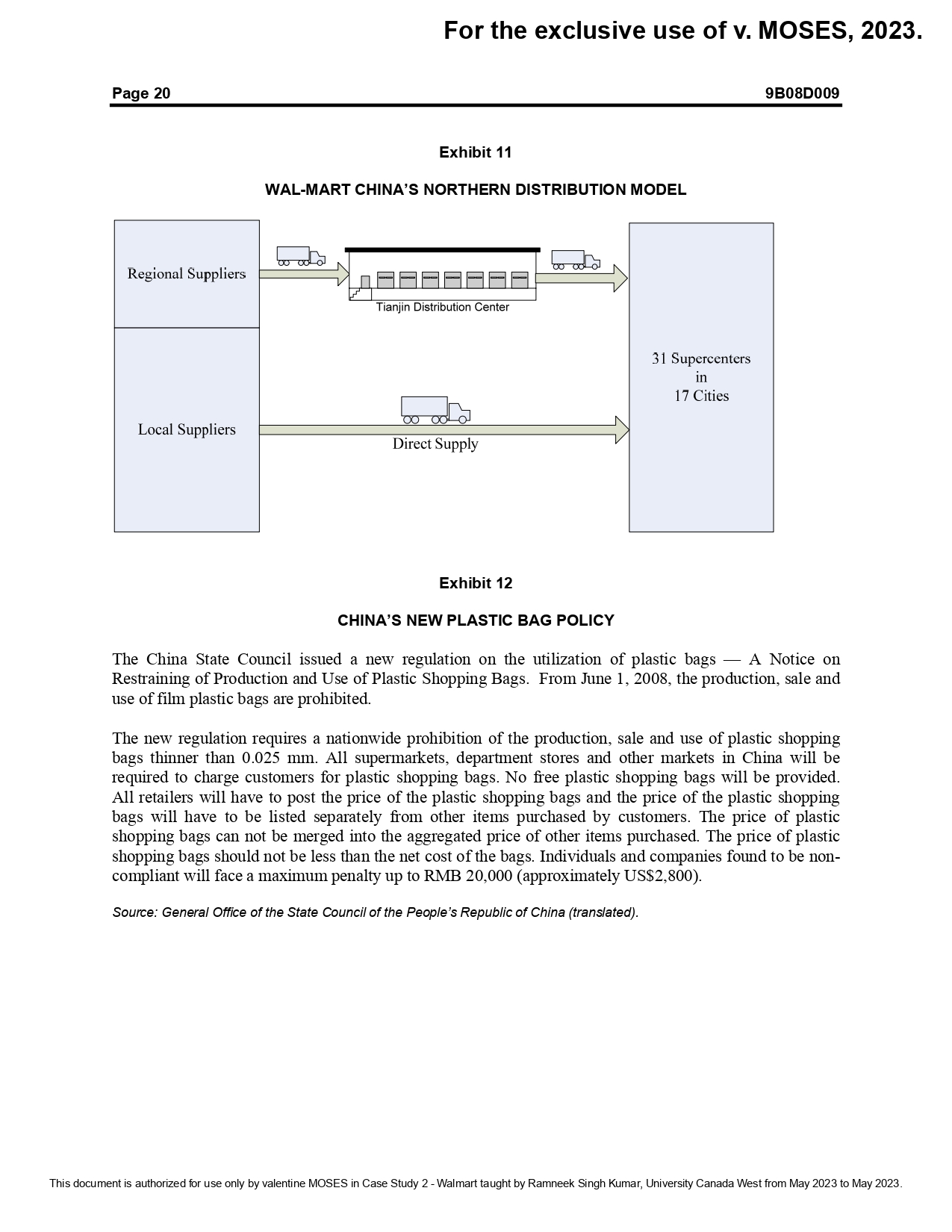

For the exclusive use of I. ALIOZOR, 2023. WAL-MART CHINA: SUSTAINABLE OPERATIONS STRATEGY Ben Hopwood, Lei Wang and Jun Cheng wrote this case under the supervision of Professor David Robb solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. Tsinghua School of Economics and Management and Ivey Management Services prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmittal without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, c/o Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Westem Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7; phone (519) 6613208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca. Copyright (c) 2009, Tsinghua School of Economics and Management and Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2009-01-21 THE CHINA SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGE The crowds following the path of the Olympic torch through the booming Chinese metropolis of Shenzhen were ecstatic. Following seven years of planning, the 2008 Summer Olympics were less than 100 days away and even foreigners were feeling the pride associated with hosting the event. Among those was JensMartin Fertsch, a German expatriate who had moved to China in late 2005 to take up a merchandizing position at the Wal-Mart China headquarters in Shenzhen. Like everyone else, Fertsch's mind was contemplating the upcoming sporting events in Beijing, but he couldn't help pondering another event in the "Northern Capital" - a three-hour flight away - for in October Wal-Mart would host its first sustainability summit in China. Lee Scott, the global CEO, would gather with around one thousand senior representatives from global and domestic partners to discuss his vision for the future - one increasingly tied to the notion of sustainability. A 12-year Wal-Mart veteran, Fertsch had just been appointed to the new position of senior director for sustainability for Wal-Mart China (retail) and Global Procurement. The dual nature of his role demonstrated the close links between China and global operations and was also reflected in his reporting to both Shawn Gray (vice-president (VP) of operations for Wal-Mart China) and Edwin Keh (chief operating officer (COO), Global Procurement). The responsibility had previously been shouldered by Gray, but rapid growth in China operations had necessitated the creation of a dedicated position. Fertsch was preoccupied with ensuring that Wal-Mart China's five "Strategic Value Networks" (SVNs), which were tasked with leading sustainability change within the organization and now directly involving some 140 associates, continued to build momentum in ways that would lead to broader acceptance among the various stakeholders. To that end, there had been literally hundreds of possible projects that had been suggested, but he and his five SVN leaders urgently needed to cull this to a handful with which to move forward. Scott would accept nothing less than innovative solutions that could both cut costs as well as lead to more sustainable operations. More pressingly, Fertsch knew that he would need to find projects that could communicate real value within the Chinese context, a market known for its high price sensitivity. For the exclusive use of I. ALIOZOR, 2023. Page 2 9B08D009 The clock was now running, as a cogent case for each project selected would need to be provided in time for the October meeting. WAL-MART'S 2005 SUSTAINABILITY VISION By the fall of 2005 , Wal-Mart was on track to exceed annual worldwide revenues of US $280 billion (see Exhibit 1). The company had grown significantly from its humble beginnings in Bentonville, Arkansas, to become a retail operation spanning thirteen countries, with over 7,000 stores, 68,000 suppliers and two million associates (see Exhibit 2). All of this had been achieved in just over four decades and was built around an unwavering commitment to low price and great service that comprised the foundation of WalMart's culture. Sam Walton, the founder, stated it this way: "Our customers are the reason we're in business, so we should treat them that way. We offer quality merchandise at the lowest prices, and we do it with the best customer service possible. We look for every opportunity where we can exceed our customers' expectations. That's when we're at our very best." The combination of this formula of value and service along with innovative operational strategies literally remapped the retail landscape in the United States (see Exhibit 3). This growth, however, had not been without cost. Along with the low prices that the company offered, Wal-Mart had been drawing an increasing amount of public criticism and legal battles ranging from contention over low health benefits for its workers to accusations of gender discrimination when it came to internal promotions. Compounding these issues was the public's growing realization of just how much power had been consolidated in one company. Even simple facts such as the company's status as the largest private user of electricity in the United States (Supercenter (SC) electricity consumption averaged 1.5 million kilowatt-hours per year per store )1 seemed to paint the company in a negative light. It was in this context of historically massive business growth and increasing public concern that CEO Scott announced what was to become a paradigm shift for the company as well as its stakeholders. In short, Scott believed that it was critical for Wal-Mart to begin leveraging its core competencies to transform itself into a worldwide leader in the area of sustainable operations. He felt that there was no intrinsic contradiction in being able to offer Wal-Mart's low prices and excellent service to its customers while at the same time reducing the company's ecological footprint. 2 To prove how serious he was about these changes, in a speech broadcast throughout all of its operations in November 2005, Scott earmarked $500 million towards sustainability projects 3 and set the following goals: - Increase the efficiency of its vehicle fleet by 25 per cent over the next three years and double efficiency in 10 years. - Eliminate 30 per cent of the energy used in stores. - Reduce solid waste from U.S. stores by 25 per cent in three years. Some within Wal-Mart perceived the initiative as simply a cosmetic change that could provide positive public relations at a time when the company was under fire. However, over the ensuing year it became 1 M. Gunther, "The Green Machine," FORTUNE, July 31, 2006. 2 Ecological footprint (EF) analysis is a measure of human demand on the earth's ecosystems and natural resources. First proposed by William Rees in 1992, its concept and calculation were developed by Mathis Wackemagel ("Ecological Footprint and Appropriated Carrying Capacity: A Tool for Planning Toward Sustainability," Ph.D. Thesis, School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia, 1994). 3 Wal-Mart Sustainability Progress to Date: 2007-2008, http://walmartfacts.com/reports/2006/sustainability/environmentFootprintClimate.html, accessed June 10,2008. ment is authorized for use only by IFEOMA ALIOZOR in Case Study 2 - Walmart taught by Ramneek Singh Kumar, University Canada West from May 2023 to May 2023. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. WAL-MART CHINA: SUSTAINABLE OPERATIONS STRATEGY Ben Hopwood, Lei Wang and Jun Cheng wrote this case under the supervision of Professor David Robb solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. Tsinghua School of Economics and Management and Ivey Management Services prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmittal without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, c/o Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Westem Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7; phone (519) 6613208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca. Copyright (c) 2009, Tsinghua School of Economics and Management and lvey Management Services Version: (A) 2009-01-21 THE CHINA SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGE The crowds following the path of the Olympic torch through the booming Chinese metropolis of Shenzhen were ecstatic. Following seven years of planning, the 2008 Summer Olympics were less than 100 days away and even foreigners were feeling the pride associated with hosting the event. Among those was JensMartin Fertsch, a German expatriate who had moved to China in late 2005 to take up a merchandizing position at the Wal-Mart China headquarters in Shenzhen. Like everyone else, Fertsch's mind was contemplating the upcoming sporting events in Beijing, but he couldn't help pondering another event in the "Northern Capital" - a three-hour flight away - for in October Wal-Mart would host its first sustainability summit in China. Lee Scott, the global CEO, would gather with around one thousand senior representatives from global and domestic partners to discuss his vision for the future - one increasingly tied to the notion of sustainability. A 12-year Wal-Mart veteran, Fertsch had just been appointed to the new position of senior director for sustainability for Wal-Mart China (retail) and Global Procurement. The dual nature of his role demonstrated the close links between China and global operations and was also reflected in his reporting to both Shawn Gray (vice-president (VP) of operations for Wal-Mart China) and Edwin Keh (chief operating officer (COO), Global Procurement). The responsibility had previously been shouldered by Gray, but rapid growth in China operations had necessitated the creation of a dedicated position. Fertsch was preoccupied with ensuring that Wal-Mart China's five "Strategic Value Networks" (SVNs), which were tasked with leading sustainability change within the organization and now directly involving some 140 associates, continued to build momentum in ways that would lead to broader acceptance among the various stakeholders. To that end, there had been literally hundreds of possible projects that had been suggested, but he and his five SVN leaders urgently needed to cull this to a handful with which to move forward. Scott would accept nothing less than innovative solutions that could both cut costs as well as lead to more sustainable operations. More pressingly, Fertsch knew that he would need to find projects that could communicate real value within the Chinese context, a market known for its high price sensitivity. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 2 9B08D009 The clock was now running, as a cogent case for each project selected would need to be provided in time for the October meeting. WAL-MART'S 2005 SUSTAINABILITY VISION By the fall of 2005 , Wal-Mart was on track to exceed annual worldwide revenues of US $280 billion (see Exhibit 1). The company had grown significantly from its humble beginnings in Bentonville, Arkansas, to become a retail operation spanning thirteen countries, with over 7,000 stores, 68,000 suppliers and two million associates (see Exhibit 2). All of this had been achieved in just over four decades and was built around an unwavering commitment to low price and great service that comprised the foundation of WalMart's culture. Sam Walton, the founder, stated it this way: "Our customers are the reason we're in business, so we should treat them that way. We offer quality merchandise at the lowest prices, and we do it with the best customer service possible. We look for every opportunity where we can exceed our customers' expectations. That's when we're at our very best." The combination of this formula of value and service along with innovative operational strategies literally remapped the retail landscape in the United States (see Exhibit 3). This growth, however, had not been without cost. Along with the low prices that the company offered, Wal-Mart had been drawing an increasing amount of public criticism and legal battles ranging from contention over low health benefits for its workers to accusations of gender discrimination when it came to internal promotions. Compounding these issues was the public's growing realization of just how much power had been consolidated in one company. Even simple facts such as the company's status as the largest private user of electricity in the United States (Supercenter (SC) electricity consumption averaged 1.5 million kilowatt-hours per year per store )1 seemed to paint the company in a negative light. It was in this context of historically massive business growth and increasing public concern that CEO Scott announced what was to become a paradigm shift for the company as well as its stakeholders. In short, Scott believed that it was critical for Wal-Mart to begin leveraging its core competencies to transform itself into a worldwide leader in the area of sustainable operations. He felt that there was no intrinsic contradiction in being able to offer Wal-Mart's low prices and excellent service to its customers while at the same time reducing the company's ecological footprint. 2 To prove how serious he was about these changes, in a speech broadcast throughout all of its operations in November 2005, Scott earmarked $500 million towards sustainability projects 3 and set the following goals: - Increase the efficiency of its vehicle fleet by 25 per cent over the next three years and double efficiency in 10 years. - Eliminate 30 per cent of the energy used in stores. - Reduce solid waste from U.S. stores by 25 per cent in three years. Some within Wal-Mart perceived the initiative as simply a cosmetic change that could provide positive public relations at a time when the company was under fire. However, over the ensuing year it became 1 M. Gunther, "The Green Machine," FORTUNE, July 31, 2006. 2 Ecological footprint (EF) analysis is a measure of human demand on the earth's ecosystems and natural resources. First proposed by William Rees in 1992, its concept and calculation were developed by Mathis Wackemagel ("Ecological Footprint and Appropriated Carrying Capacity: A Tool for Planning Toward Sustainability," Ph.D. Thesis, School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia, 1994). 3 Wal-Mart Sustainability Progress to Date: 2007-2008, http://walmartfacts.com/reports/2006/sustainability/environmentFootprintClimate.html, accessed June 10,2008. ument is authorized for use only by valentine MOSES in Case Study 2 - Walmart taught by Ramneek Singh Kumar, University Canada West from May 2023 to May 2023. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 3 9B08D009 clear, according to Fertsch, that the initiative was truly "implanting something green into (Wal-Mart's) DNA." Wal-Mart organized its efforts in the United States into 14 SVNs that included categories such as store operations, electronic products and packaging (see Exhibit 4). While Wal-Mart began to draw widely upon many outside resources for recommendations and ideas, there were only a few associates tasked full-time with developing these SVNs. Instead, the company put the networks together by giving top-performing managers the responsibility of integrating the sustainability initiatives alongside their current workload. Ideas for projects were categorized in three ways. "Quick wins" were projects that the business and stakeholders could begin immediately. This meant that the concepts would be quickly understood and the project would result in a short-to-immediate payback period. "Innovation projects" were to combine recently available technologies and methodologies that would result in payback periods ranging from one to three years. Finally, "game changers" would be pursued on an ongoing basis and were paradigm shifts intended to result in radical departures from traditional business practice. By 2007, significant changes had occurred throughout the company. Many of the internal goals that Scott had put forth were well on their way to completion. Wal-Mart had become the largest seller of organic milk and the largest purchaser of organic cotton. There had been large changes in product selection within the categories of seafood, electronics and textiles, along with major changes in the ways that Wal-Mart's suppliers were scored and selected. From a public standpoint, the company had successfully partnered with GE to sell over 110 million compact fluorescent lighting (CFL) units in the United States that year. Despite the fact that it would effectively cannibalize its incandescent product sales, the greater efficiencies and longer bulb life meant that Wal-Mart's customers would save well over $3 billion, conserve 55 billion tons of coal and keep 1.1 billion incandescent light bulbs out of landfills. It was with these initial wins in the United States that Wal-Mart's executive team began to gear up for Wal-Mart's international sustainability initiative. Wal-Mart China's associates, customers, supplier base and the surrounding communities were significantly different from the stakeholders of other international operations. As such, the solutions and standards that had been pioneered in other regions could provide direction to Wal-Mart China's sustainability initiative, but would not necessarily result in immediate wins. Instead, its SVNs and associated projects would need to be contextualized to the unique challenges and values of the China market. THE CHINA RETAIL ENVIRONMENT In 1994, Wal-Mart had begun to investigate what would be needed to launch retail operations in China. Its first SC was opened in the southern city of Shenzhen in 1996. Expansion continued for Wal-Mart China at a hobbled rate due to the lengthy application processes necessary for each new location that required authorization by both local and central government agencies. Coupled to these applications were severe restrictions in the overall allowable store count per city as well as location. By mid-2008, Wal-Mart China had 106 SCs located throughout the country, 101 Trust-Mart stores (35 per cent stake acquired in 2007) and two distribution centers (DCs) located in Shenzhen and Tianjin, with a third scheduled to open later in the year in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province. While many of Wal-Mart's core values and rules had been directly translated into the Chinese context, such as the ten-foot greeting rule being changed to three meters, the company faced significant strategy changes necessitated by the operating environment. Third-party studies and internal research had shown that Chinese customers were significantly more cost-sensitive than those in other countries and that there For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 5 9B08D009 - Sustainable stores and operations: Included Wal-Mart's DCs, its outsourced third party logistics (3PL) providers, retail stores and office spaces. Its goal was primarily to decrease the company's overall footprint of operations and to reduce cost. An example of this was Wal-Mart's research into energy efficient lighting and its implementation throughout its operations. - Sustainable products: There were four primary categories in this SVN which represented the areas where Wal-Mart felt that it could affect the most difference in its overall sustainability. The current areas were food, electronics, textiles and product packaging. - Supply chain compliance and standards: Covered all of the standards Wal-Mart required for its products as well as the compliance levels set by local governments. It also included oversight of manufacturing processes. Some of the standards were unique to Wal-Mart and others were local standards that Wal-Mart then projected worldwide. An example of the latter was the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (ROHS) code originating in the United Kingdom that Wal-Mart had begun to adopt as more and more retail markets worldwide strengthened their requirements for compliant products. - Supply chain efficiencies: Went beyond the standards for compliance that Wal-Mart imposed on suppliers and looked at the entire supply chain to determine what actions would most improve efficiency, reduce cost and reduce the footprint of the entire chain. This included areas like Fleet Management best practices, which described how best to ship products from the DC to stores, from ports to the United States and from the U.S. ports to U.S. DCs. Additionally, it included supplier relationships and explored indirect ways Wal-Mart could offer assistance to its vendors and the various ways that it encouraged its suppliers to take steps to reduce electricity usage. - Communications: Critical in making Wal-Mart's actions and direction transparent to the outside community, the communications SVN sought to implement best practices for communicating to all of Wal-Mart China's stakeholders. The October 2008 meeting of key leaders in Beijing was considered to be a critical test for this SVN in demonstrating the ways Wal-Mart China was seeking to develop a common vision and understanding among its stakeholders. WAL-MART CHINA'S OPERATIONS GROUP Wal-Mart China's operations group was made up of senior directors and VPs under the COO that oversaw Trust-Mart, Supercenter operations, Supercenter merchandizing, Sam's operations, Sam's merchandizing, marketing, supply chain and logistics and private brands (see Exhibit 8). Merchandizing Operations All supplier relationships for Wal-Mart China fell under the responsibility of Mimi Lam (VP Supercenter merchandizing), who oversaw product and supplier selection as well as on-going evaluation. While WalMart's international stores sourced from a well-established network of suppliers developed and managed by the Global Procurement division, all domestic procurement was handled by Supercenter merchandizing. There were two primary reasons for this seeming redundancy. Firstly, Chinese law required that companies be licensed for either import/export or for domestic production. It was not possible to be licensed for both. In response, many multinational companies set up holding companies with both types of subsidiaries but the common result was often two very different sales forces. Secondly, a large portion of the most popular Chinese suppliers had yet to test foreign markets with its products and so was still unknown to Global Procurement. Customers coming to Wal-Mart stores in China would expect to see products that they were familiar with at prices at or below those of the competition. Thus, Wal-Mart China's merchandizing group For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 6 9B08D009 was allowed to approach suppliers to facilitate closer relationships with the SCs and to improve performance. As suppliers were responsible for delivering their product to Wal-Mart's DC or, in the case of some products, directly to the SCs (Direct Store Delivery or DSD), the merchandizing group did not have to involve the supply chain group in making decisions concerning product transportation to Wal-Mart locations. There were a number of programs to encourage best practices throughout Wal-Mart China's supplier network. One such example was the supplier collaboration group comprised of its top vendors that had been chosen to meet together to share learned experiences. The top-scoring companies from this group comprised the board (Blue Moon, Johnson and Johnson, Kimberly-Clark, Kraft, P\&G, SC Johnson, Unilever and Colgate). Among the board members, P\&G was an example of a large multinational supplier with a long-standing working relationship with Wal-Mart in other parts of the world. Its size had resulted in close scrutiny from environmental watchdog groups and thus a greater transparency on the part of the company. It defined its commitment to sustainable development as "ensuring a better quality of life for everyone, now and for generations to come" and had sustainability programs throughout its worldwide operations. This could be compared to fellow board member Blue Moon, a Chinese national chemical products company supplying the number one hand soap, toilet cleaner and floor cleaner in China, who represented one of the few seats occupied by a domestic-only supplier. Begun in 1994, Blue Moon was a relative newcomer but moved quickly to comply with internationally accepted standards such as ISO14001 certification. Its policy was that, "Protecting the environment is protecting all of us. Our products deliver not only cleanliness but also protection to our customers." To ensure this, Blue Moon used biodegradable materials in its products with no aluminum or phosphate (see Exhibit 9). Wal-Mart China also encouraged participation among its suppliers in third-party initiatives such as the P2E2 (Pollution Prevention Energy Efficiency) program that allowed suppliers to quickly and inexpensively equip their factories with costsaving equipment (see Exhibit 10). Wal-Mart China's merchandizing group was also continuing to build sustainability into the evaluation tools it used for supplier selection and on-going evaluation of purchase quantities. However, moving towards sustainability often involved working with vendors over long periods of time to allow them to make the changes necessary to come into compliance. Government agencies as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) had strongly encouraged Wal-Mart to not drop companies that failed standards but, in light of China's "Harmonious Society" policy, to give its vendors the time needed to move towards compliance. DISTRIBUTION CENTER OPERATIONS Wal-Mart's new 43,000-square-meter DCs had been specifically designed by wholly owned subsidiary Gazeley as next-generation sustainable logistics centers. While the Tianjin DC participated in standard sustainability practices such as helping its associates conserve fuel by busing them from predetermined locations in the city and reselling all of its used cartons, pallets and plastic sheeting, there were other fundamental differences that set the facility apart. The lighting of warehouse areas was supplemented with day lighting and T5 energy saving light bulbs were used throughout the rest of the facility, resulting in energy savings of 20 to 30 per cent. Air conditioning and heat recycling systems maintained consistent temperatures with less waste. Ten solar energy water heaters provided 1.7 tons of hot water a day projected to save up to 25,550 kilowatt hours each year. Additionally, the DC prominently displayed two 20 -squaremeter-wide solar cells and two 10-kilowatt wind power generators that together could generate up to 7,300 For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 7 9B08D009 kilowatt hours per year. Wal-Mart claimed that, as a whole, these systems helped each distribution center reduce 31 tons of CO2 emissions every year. When asked about the concept of sustainability, however, staff downplayed its more visible differences. Connie Wu, assistant general manager of the Tianjin DC, stated, "When people talk about sustainability, they normally first point to the systems that were designed into the facility. Sustainability, however, goes far beyond that. It includes the cartons that the material comes packed in as well as the trucks that we unload and load each day." In contrast to the United States, where over 90 per cent of total store sales passed through DCs, only 40 per cent of Wal-Mart China's sales were supplied via its DCs. Fresh products such as bread, fsh, vegetables and fruit, along with some electronics goods and high-value items, were sent directly to the SCs by suppliers (DSD) (see Exhibit 11). These shipments from individual suppliers arrived at the SCs throughout the day. One challenge was the lower-than-expected fill rates (order completeness) for some products supplied to the DSD. Products arriving at the DC were from vendors in the region or were inter-DC shipments. Whereas WalMart outsourced a standardized trucking fleet (average capacity of 81.5 meters cubed, equivalent to a 40foot-"high" container) for all of its DC-DC and DC-SC shipments, incoming shipments from suppliers arrived in a diverse range of trucking and loading configurations. While a far cry from the early years in China when some goods arrived on the back of bicycles, the responsibility of incoming goods transport was left to local suppliers and resulted in different truck types, with high stacks of goods and little to no use of pallets. All loading and unloading was accomplished by hand using a 3PL provider. The cartons were tagged with their routing numbers as they arrived and palletized for transport within the facility. They were then moved to either the "stable inventory" - part of Wal-Mart's safety stock that remained at the DC for more than 30 days - or were passed into the "normal inventory," where it was hand-sorted and then routed to either SCs or the Shenzhen DC in less than a day. Boxes were loaded onto trucks without using pallets and seeking to maximize space utilization. The Tianjin DC had about 70 doors on each side for incoming and outgoing products. Thirty-two doors on the outgoing side were reserved for the SCs and the Shenzhen DC and 10 were reserved for Trust-Mart stores. Goods traveling between the DCs accounted for approximately four to six trucks per week incoming from Shenzhen and one-half to one truck per week outgoing to Shenzhen. Shipments to stores, averaging 25 trucks per day, took place when there was enough merchandise to fill an entire truck. Daily capacity was expected to reach 330,000 cases in full operation - four times that of the old DC opened in 200335 Whereas DSD lead times were generally only a few days, shipments supplied via the DCs required several weeks from the time the order was placed on the supplier. The average transportation time from DC-store was about two days, but could be higher due to poorer transportation infrastructure (e.g. from Shenzhen to Kunming could take four days) or the requirement for inter-DC movement (e.g. Shenzhen DC to Harbin via the Tianjin DC took about two weeks). The DC also received six to eight truck loads (22 pallets per truck) per week of products returned from stores due to obsolescence, slow sales or in some cases, quality problems. A return to vendor program was in place to handle these situations. The DC normally reserved space for approximately 1000 pallets of 5 "Wal-Mart Relocates Tianjin Distribution Center," http://www.chinaretailnews.com/2007/11/20/923-wal-mart-relocatestianjin-distribution-center, accessed July 29, 2008. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 8 9B08D009 goods waiting to be returned to suppliers. However, this ballooned to about one-sixth of warehousing floor space soon after holidays such as the Chinese Spring festival. Supercenter Operations Operationally, Wal-Mart China offered around 25,000 stock keeping units (skus) per store. While this variety was only about a quarter of that provided in its U.S. stores, it was similar to that provided by its foreign competitors and higher than that provided by most domestic competitors. Based on Wal-Mart's internal data, the company's in-stock rate was in the high 90s - significantly higher than the industry reported average of 90 per cent in 2003.6 Wal-Mart's estimated inventory was consistent with the report's estimate of a national average of 25 to 40 days. In comparison to its DCs, Wal-Mart China had been much more limited in opportunities to design sustainability into its SCs. While it employed T5 energy efficient light bulbs and there were initiatives to reduce waste, it was a different situation to the United States, where most of Wal-Mart stores started as greenfield projects. Instead, store managers felt their greatest contribution to sustainability came through the types of products they promoted and the shopping behaviors they encouraged. Baker Jiang, the Northeast Regional director of operations, commented this way: "We see sustainability issues in everything from the lighting that this store uses to the fact that we ask all of our associates to print on both sides of a page of paper. For the higher level managers there are also personal training sessions where the company helps you to identify places in your personal life that, if changed, could result in a more sustainable environment." Reusable shopping bags was one area where Wal-Mart China had sought to provide a more sustainable alternative to its customers. The company partnered with Unilever to design a 10RMB cloth bag and then defrayed 70 per cent of the cost, only asking the customer to pay three RMB. Wal-Mart then set up a special express checkout line for customers using the bags and gave prizes to those who used the bag five times. These initiatives came prior to the Chinese government's announcement that as from June 2008 shops throughout the country would be prohibited from offering thin film bags and would have to visibly charge a separate fee for thicker plastic bags (see Exhibit 12). In response to the change in legislation, WalMart China was preparing further initiatives in this area that were likely to be unveiled at the October 2008 meeting. Product Inspection When operations first began, the Wal-Mart DCs in China opened all of the cartons received from vendors. However, with the tightening of government regulations and improvements in supplier reliability, they had moved to either sampling or, in the case of worldwide partners such as P\&G, to omitting the inspection altogether. Currently, the only products that were fully inspected were those that needed to be taken out of their initial packaging and repacked into mixed shipments bound for SCs. These inspections were primarily to comply with tight government regulations on disclosing the shipping contents of all cartons. Inspection at the DC entailed both a cursory check upon arrival to see if the general amounts were correct and whether there was any obvious damage and a subsequent check, for legal reasons, to confirm that 6 H. Drinkuth, S. Yeung and F. Zheng, Supply Chain Excellence in Chinese Grocery Retailing, Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, Shanghai, 2003. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 9 9B08D009 quantities matched those listed on government-required documents. Stores inspected DSD shipments, but did not inspect shipments from DCs. The trucking options and hand loading and unloading took a toll on the outer packaging, with many cartons visibly damaged by the time they arrived at the store. Wal-Mart China's experience, however, was that breakage prior to reaching the shelves was quite small. Return to Vendor It was common in China for larger retailers to have negotiated agreements with suppliers allowing for the return of goods that were slow to sell, had quality problems or had been returned by customers in unsalable condition (Wal-Mart offered its customers a 90-day no questions asked return policy for sales of nonperishable goods). Although such return to vendor (RTV) programs were costly, suppliers saw some benefit in avoiding the erosion of product value which could follow price discounting - something more common in the United States. Instead, the Chinese retail/vendor relationship often saw slow-selling items enter a "reverse logistics" process, with the product stored (at the DC, or the store in the case of DSD goods) until goods were reclaimed by suppliers or destroyed. In reality, the actual 14-day grace period for collection was often stretched by suppliers -some suppliers appeared to view Wal-Mart's leniency as an opportunity for free warehousing. While Wal-Mart sought to sell its entire inventory, sometimes using internal competitions and bonus programs that rewarded SCs that sold the most of certain types of products, the cost of reverse logistics returns was still significant. As such, Wal-Mart was seeking to convince suppliers that discounting unsold product may be preferable to reverse logistics, but it had not been able to find many suppliers willing to provide a small discount in return for ending the RTV program. LOCALIZED SUSTAINABILITY Many of the most challenging questions of sustainability concerned resolving the differences in standards and values around the world. Wal-Mart had to account for the varying government regulations, levels of developed infrastructure and customer preferences of the communities throughout its operations. For instance, Wal-Mart had begun to adopt ROHS compliance as a standard in some of its operations with regard to the selection of suppliers and their products. The company had also determined that it could positively impact the global community by promoting CFL bulbs. However, a seemingly simple question like whether to promote these light bulbs in its China region resulted in hours of discussions. The point of contention lay in the fact that each bulb contained a very small amount (less than five mg) of mercury. That level of mercury posed no significant danger by itself, but when multiplied by thousands of light bulbs in a landfill, it created a significant footprint if not recycled properly. Countries like the United States and Germany already had much of the required recycling systems in place to handle this sort of product, but China did not. With most bulb lifetimes being measured in years instead of months, the necessary infrastructure could possibly be developed after sales significantly picked up, as had been the case for CFLs in much of the United States. However, while Wal-Mart could work with suppliers and government agencies to lower the mercury levels in the product and to incorporate recycling costs into the initial sales, there was still the question of who was responsible if certain commitments were not met. However, after much debate at Wal-Mart China and the successful sale of 110 million CFL units in the United States, Wal-Mart China decided to begin working with local suppliers to promote the bulbs in its region. It was able to offer two energy-efficient bulbs for the price of one and planned internal competitions to encourage stores to strongly promote the product. By the end of the promotion, Wal-Mart had sold the majority of its initial stock, but a major increase in consumer purchasing had not materialized and many of its stores were For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 11 9B08D009 and had resulted in significant public backlash. Consumer confusion over mercury in CFL units was an example of this danger. It was risky for Wal-Mart to make statements until there was more certification of sustainable standards. A European example of this kind of certification movement was Oeko-tex, an organization in Germany that defined standards for textile products - from fiber to ready fabric. But until a time in which these standards and certifications were more developed in China, Fertsch's team would need to move forward carefully so that the communications it released to its suppliers, associates and customers were both true and could stand the test of public scrutiny for years to come. CHALLENGING DECISIONS Jonathan Dong (director of public relations) said, "Sustainability will be a differentiating factor between a good enterprise and a great one. It takes vision, leadership, and courage to commit to such a challenge. All the environmental sustainability initiatives being implemented at Wal-Mart are not something we do for public relations mileage. Rather, we are grasping an historic opportunity to put Wal-Mart on a solid footing for long-term, sustainable growth." History would ultimately look back and judge the full effect that Wal-Mart China's sustainability focus would have on its stakeholders. Fertsch and his team's initial challenge, however, was to lay out the next steps for Wal-Mart China's SVNs and to clearly demonstrate to their stakeholders at the October summit that sustainability in the Chinese context could be not only better, but also more profitable. In particular, Fertsch wanted to identify a few of the many possible projects to serve as examples and to show summit participants the range of possibilities in China. He also wanted to identify key facts that attendees from abroad would need to understand about Wal-Mart's China's situation and options. Finally, he wanted to outline some principles that should be used to decide which projects to pursue. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 12 9B08D009 All financial data is in US\$ millions. Fiscal year ends January 31. Source: Wal-Mart Annual Reports, http://walmartstores.com/Investors/7666.aspx. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 13 9B08D009 Exhibit 2 WAL-MART'S INTERNATIONAL DATA SHEET AS OF JUNE 2008 * Including a 35 per cent interest in Trust-Mart, which operates 101 stores in China. Source: Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. - Facts \& News. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 14 9B08D009 Exhibit 3 WAL-MART CULTURE AND RULES Source: Wal-Mart Stores, Inc - Culture. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 15 9B08D009 Exhibit 4 UNITED STATES' SUSTAINABLE VALUE NETWORKS Source: Shawn Gray, vice-president - operations, Wal-Mart China, Wal-Mart current sustainability project introduction. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 16 9B08D009 Exhibit 5 CHINESE CONSUMER SATISFACTION SURVEY Adapted from: Wang Gao, Li Fei and Lu Qibin, Chinese Supermarkets Customer Satisfaction Research, School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University. Used with permission. About the survey: The data used in this survey is derived from the results of random sampling surveys in 2005 measuring customer satisfaction with supermarkets, conducted with a Computer Assisted Telephone Investigation (CATI) system, by China Retail Research Center, Tsinghua University. The survey studied 20 large supermarkets in eight large cities and interviewed 5028 customers. The study showed that there is only a small amount of differentiation between supermarkets based on customer satisfaction. However, among the differences found, perceived value is the most important element in customer satisfaction. Perceived value is composed of three sub-factors: product price, relative price to other supermarkets and promotions. This was followed in importance by image, merchandise and shopping environment. Service, check-out process and store policy are less significant in affecting customer satisfaction. Shop facilities and shopping convenience have nearly no impact on customer satisfaction. The customer satisfaction level greatly influences customer loyalty. The survey found that all foreign supermarkets ranked above average. Wal-Mart was ranked no. two in the survey, while Carrefour was no. seven and Wu-Mart was no. 17. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 17 9B08D009 Exhibit 6 CHINESE HOUSEHOLD INCOME BY CLASS Note: income in US\$. Source: McKinsey Quarterly. Used with permission. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 18 9B08D009 Exhibit 7 HOUSEHOLD DISPOSABLE INCOME IN CHINA Source: adapted from Euromonitor International from IMF and National Statistics, 2006. Exhibit 8 WAL-MART CHINA ORGANIZATIONAL CHART Source: Wal-Mart China. For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Industry status: The brand awareness of Blue Moon is 88.74 per cent. Customer satisfaction is 97.40 per cent. In 2006, Blue Moon ranked fourth in China's daily chemical industry. The market shares of its hand wash, toilet cleaner and floor cleaner all ranked \#1 in China. Note: data compiled from CVSC-TNS Research (CTR). Green policy: Blue Moon's environmental policy is, "Protecting the environment is protecting ourselves. Our products deliver not only cleanliness but also protection to our customers." The ingredients Blue Moon uses are biodegradable materials, with no aluminum and phosphate. It has promoted environmental awareness and protection in China and has gained ISO14001 certification. Source: Blue Moon company website, http://www.bluemoon.com.cn Exhibit 10 P2E2 The P2E2 (Pollution Prevention Energy Efficiency) program based in Hong Kong is an environmental finance business model based on a United States-China program that encourages environmental cooperation. There are two key features of this program: (1) end users in mainland China that have either a Hong Kong parent or subsidiary company may obtain P2E2 technology upgrades to their factories, power plants or real estate developments from a Hong Kong-based - "Environment and Energy Service Company" (EESCO) with no upfront, or extra capital cost, and subject to a performance contract assigned between the two Hong Kong companies; and (2) Hong Kong-based EESCOs are paid in hard currency in Hong Kong for all P2E2 technical upgrade work done in Asian developing countries, including mainland China. Financing for P2E2 projects is provided by Hong Kong commercial banks as working capital and trade finance loans that benefit from loan guarantees, loan syndications, direct investment and other support from the Asian Development Bank and the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group. In short, companies in China that have a Hong Kong parent are eligible for free upfront upgrades to their current equipment through P2E2. In return, the companies agree to pay savings accrued from the upgrades back to the P2E2 investors over a given time period. Source: United States Commercial Service, http://www.buyusa.gov/hongkong/en/about_p2e2.html For the exclusive use of v. MOSES, 2023. Page 20 9B08D009 Exhibit 11 WAL-MART CHINA'S NORTHERN DISTRIBUTION MODEL Exhibit 12 CHINA'S NEW PLASTIC BAG POLICY The China State Council issued a new regulation on the utilization of plastic bags - A Notice on Restraining of Production and Use of Plastic Shopping Bags. From June 1, 2008, the production, sale and use of film plastic bags are prohibited. The new regulation requires a nationwide prohibition of the production, sale and use of plastic shopping bags thinner than 0.025mm. All supermarkets, department stores and other markets in China will be required to charge customers for plastic shopping bags. No free plastic shopping bags will be provided. All retailers will have to post the price of the plastic shopping bags and the price of the plastic shopping bags will have to be listed separately from other items purchased by customers. The price of plastic shopping bags can not be merged into the aggregated price of other items purchased. The price of plastic shopping bags should not be less than the net cost of the bags. Individuals and companies found to be noncompliant will face a maximum penalty up to RMB 20,000 (approximately US\$2,800). Source: General Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China (translated)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started