Question

Andrew Cha, the founder of Colorscope, Inc., a small, vibrant firm in the graphic arts industry, had seen his business change dramatically over the years.

Andrew Cha, the founder of Colorscope, Inc., a small, vibrant firm in the graphic arts industry, had seen his business change dramatically over the years. The rapid development of such technologies as desktop publishing and the World Wide Web as well as the consolidation of several major players within the industry had radically altered his company?s relative positioning on the competitive landscape. Preparing to celebrate the company?s 35th anniversary on March 2013, Cha pondered the issues involved in moving Colorscope ahead.

Company History

Born in Anhui, China, in 1938, Andrew Cha immigrated to the United States in 1967 to seek a better life. Cha worked as a cook and busboy in a downtown Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles, but he eventually found jobs that took advantage of his artistic skills in draftsmanship and photography. A succession of promotions in one graphic arts company convinced him that he had the skills to start his own business. On March 1, 1976, Cha founded Colorscope, Inc, as a special-effects photography laboratory serving local advertising agencies in southern California.

As Cha?s reputation grew, so did the business. Sales increased steadily over the years. The company served agency giants such as Saatchi & Saatchi, Grey Advertising, and J. Walter Thompson and large retailing and entertainment companies such as The Walt Disney Company and R. H. Macy & Co. To improve service to these customers, Cha invested in expensive proprietary computer equipment to continue providing ever more complicated print special effects.

While serving his existing base of high-margin clients, Cha ignored certain trends in the business, particularly the price pressures brought on by cheaper PC- and Mac-based microcomputers. These computers were equipped with increasingly sophisticated page layout and color correction software, so small ad agencies and print shops began to take pieces of business away from larger graphic art companies like Colorscope. Cha, however, had felt protected from the trend by the strong personal relationships he had built with key clients over his career.

Market pressures, however, forced Cha to reduce his own basic prices. This, however, proved to be insufficient. His largest account, representing about 80% of his business, announced that it was purchasing its own graphic design and production equipment, replacing Colorscope with an internal group. To rebuild the business, Cha had to reevaluate the industry, his company?s position in the prepress segment, its pricing policy, and its operations.

The Prepress Production Process

Although technology dramatically changed the means by which production was conducted as well as the corresponding values to each phase, the basic process for print material, known in the industry as prepress or color separations, remained essentially the same. A content provider, such as a magazine or direct mail cataloger, designed and laid out a ?book? or ?project? for distribution (1 week). Once the book?s layout was approved, a photographer captured and developed the images, received approvals from the client, and sent them to the prepress house or ?color separator,? in this case Colorscope (1 week). Once in production, images were processed or digitized via laser scanner and compiled with text and other graphics to form a master file for the printer (2 weeks).

During this process, the magazine or direct-mail client saw iterations, or proofs, of their ?book? with digital and conventional proofing devices. At these intervals, the clients could ask for changes, ranging from simple price and copy adjustments to sophisticated special effects, adjusting colors, or clearing blemishes in products and people. A very important qualitative component of the separator?s task was to understand the product?s desired ?look and feel? and translate the direction the client desired into the actual images on each page. Typically, the prepress house charged a base rate for digitizing, assembling, and proofing each page, with an additional fee for the special effects. When the ?books? were ultimately produced on paper, the images were filed and stored in the separator?s database for future use.

After the client approved the project, Colorscope sent the ?master book,? or file, to the printer electronically. At this point, the separator had converted all of the client?s information, digital text, graphics, and photographs (described in a postscript or dpi format) into a printer-acceptable (line screen) format. Printing took about 1 week.

Industry Dynamics

For the individual prepress firm the market had drastically changed. Thus Colorscope?s previous position as a high-quality, high-service player appeared unsustainable in a marketplace full of service providers that claimed the same quality at lower prices. While in the past prosperous relationships could last several years, with customers consistently able and willing to pay for top quality separations, current technology blurred the clear distinctions in quality of the actual output. As more prepress houses bought desktop equipment and lowered their prices, customers in the catalog arena defected to even lower-cost providers. Given that the basic scanning and proofing functions of a prepress house could be easily replicated on a smaller scale with minimal investment, and given the significant overcapacity in the industry, Cha knew that the downward pressure on prices was likely to continue.

1 Local service bureaus could scan color film, layout pages, and output printer-specified film with a minimal capital investment of less than $100,000.

Direct Competition

Although the number of larger direct-mail clients had remained flat for several years, the competition for them was intense. Cha?s competitors came in three main types. First were larger, more technically savvy printing companies, such as R. R. Donnelley & Sons Co, and Quad Graphics, with professional salespeople pushing bundled pricing, integrating prepress services with printing in a single package. Another significant rival type was represented by the horizontally integrated national prepress houses or ?trade shops? such as American Color and Wace/Techtron?highly entrenched, multimillion-dollar prepress service providers backed by national sales networks of service professionals and multiple physical plant locations across the United States. These companies competed in several different submarkets beyond catalogs, for example, inserts, comic syndications, and coupons. A third rival type comprised other standalone firms that competed with loose affiliations to other printers or advertising agencies, or that literally set up shop next door to their largest accounts to fend off potential competitors. Cha currently lacked a sales infrastructure similar to that of these competitor types.

Work Flow Organization at Colorscope

A ?job? at Colorscope began when the customer placed an order. Customer service representatives interacted with the customer on the phone and recorded the job specification details. Each order was ?owned? by a particular representative, who, based on the specifications, did a ?job preparation.? A separate ?job bag? was opened for each set of four pages for the order. The template of the job was created by physically cutting and pasting text, graphics, and photographs; extensive markings on the template specified the changes in font, color, shading, and layout. The next step in the production process was scanning, whereby the pictures were digitized and output as a computer file. Colorscope had three laser scanners.

The following step was assembly, performed on nine high-end Macintosh computers, each with oversized computer terminals. The computers were networked and hooked up to the scanners, output devices, and a powerful file server that contained archives of optical images. Operators worked on the computers composing the ?job? with scanned images and text input from the keyboard. At this stage the operators changed colors and shades of the scanned picture to the exact specifications the customer demanded. Once a job was fully assembled, it was output on one of two high-end output devices. The output was a large sheet of four-color film that was then developed.

The ?job? then flowed to Quality Control (QC) for proofing, where an employee compared the hardcopy output with customer specifications. Reworks were initiated at this stage. QC might, for instance, require the job to be rescanned if it determined that the original scanning was flawed. The rescanned image would then have to be reassembled, re-output, and pass QC all over again. Once a job passed QC, it was shipped to the customer?s printer either on a computer disk or, more usually, on film.

Colorscope?s operators were cross-trained and could work at any stage of the production process. Work flow and production procedures were standardized but not documented. Colorscope relied instead on the institutional knowledge of its employees and frequent supervision by Andy Cha to maintain and improve operational efficiency.

The Future

Cha realized that Colorscope had to capitalize on its biggest assets, its employees, who were all well trained and worked effectively as a team to meet deadlines. The short-term strategy was to increase marketing efforts to drum up new business for the lean months that preceded the huge rush of orders to do prepress for catalogs in the fall season before holiday shopping started. Colorscope Exhibit 1 gives details of jobs completed in June 2012 and revenue generated from each customer. Revenue per page, however, was unlikely to improve due to competitive pressures. Cost containment and improving operational efficiency were therefore critical, particularly in reducing the amount of rework. This effort required the cooperation of its workers, and Cha was considering sharing the gains of such improvement with its employees. With this objective in mind, Colorscope began tracking hours spent on rework, which was broken down into hours spent on rework initiated by customer due to change in specifications and rework caused by errors in-house. Colorscope compensated its line workers on an hourly wage basis. To keep track of hours worked, employees logged the hours spent on various jobs into a centralized computer from remote terminals. (Colorscope Exhibit 2 gives the hours spent at different workstations by different jobs in June 2012.)

Colorscope Exhibit 1

Jobs Completed in June 2012*

* All figures are disguised.

Tracking rework hours was fairly straightforward; employees recorded both types of rework hours separately for each job. (Colorscope Exhibit 3 gives the rework hours recorded during June 2012.)

Another area for improvement was product pricing. At present, Colorscope quoted more or less the same per-page price for different customers, plus additional charges for special effects. Yet different customers placed different demands on organizational resources, and this was not appropriately reflected in the price charged. However, Colorscope could not afford expensive accounting systems or to hire consultants to design a state-of-the-art activity-based cost system. Colorscope Exhibit 4 gives selected financial information and Colorscope Exhibit 5 gives materials expense, broken down by jobs, for the month of June 2012.

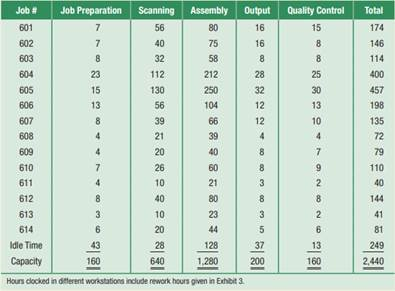

Colorscope Exhibit 2

Hours Clocked at Different Workstations in June 2012*

* All figures are disguised.

Colorscope Exhibit 3

Rework Hours*

Rework due to change in specifications by customer

* All figures are disguised.

Quality Control initiated rework of house errors

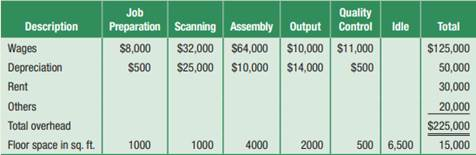

Colorscope Exhibit 4

Selected Financial Information for June 2012*

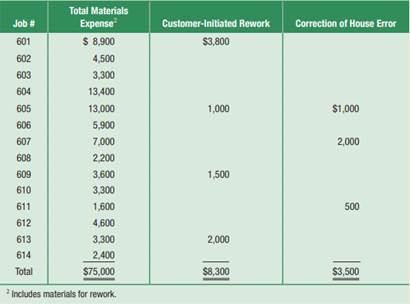

Colorscope Exhibit 5

Materials Expense in June 2012*

* All figures are disguised.

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Copyright ? 2012 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College Harvard Business School case 9-113-025 The case was prepared by VG Narayanan as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

Required

Set up a two-stage cost system to calculate the profitability of different jobs. You will have to choose resource drivers to allocate the cost of resources to cost pools. Then choose cost drivers to allocate the costs in various cost pools to jobs. Compute the cost driver rates. Calculate profitability of all jobs by allocating costs to jobs using the cost-driver rates that you estimated. It might be useful to diagram this system before you start calculating the cost pools and cost-driver rates.?

?Job # 601 602 603 604 605 606 Job Preparation 7 7 8 23 15 13 8 4 7 3 Scanning Assembly 56 40 32 43 160 112 130 56 39 21 20 26 607 608 609 610 611 612 80 613 23 614 44 Idle Time 128 Capacity 1,280 Hours clocked in different workstations include rework hours given in Exhibit 3. 10 40 10 20 80 75 58 28 640 212 250 104 66 39 40 60 21 Output 16 16 8 28 32 12 12 8 8 3 8 3 5 37 200 Quality Control 15 8 8 25 30 13 10 4 7 9 2 8 2 26 6 13 160 Total 174 146 114 400 457 198 135 72 79 110 40 144 Fang 41 81 249 2,440 Description Wages Depreciation Rent Others Total overhead Floor space in sq. ft. Job Preparation Scanning Assembly Output $8,000 $32,000 $64,000 $10,000 $11,000 $25,000 $10,000 $14,000 $500 $500 1000 1000 4000 Quality Control Control Idle 2000 500 6,500 Total $125,000 50,000 30,000 20,000 $225,000 15,000 Job # 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 Total Materials Expense $ 8,900 4,500 3,300 13,400 13,000 5,900 7,000 2,200 3,600 3,300 1,600 4,600 608 609 610 611 612 613 3,300 614 2,400 Total $75,000 Includes materials for rework. Customer-Initiated Rework $3,800 1,000 1,500 2,000 $8,300 Correction of House Error $1,000 2,000 500 $3,500

Step by Step Solution

3.27 Rating (150 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Colorscope can improve its operations by training employees and upprinting technology equipment to become faster and more efficientultimately become more profitable by continuing there marketing effmo...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started