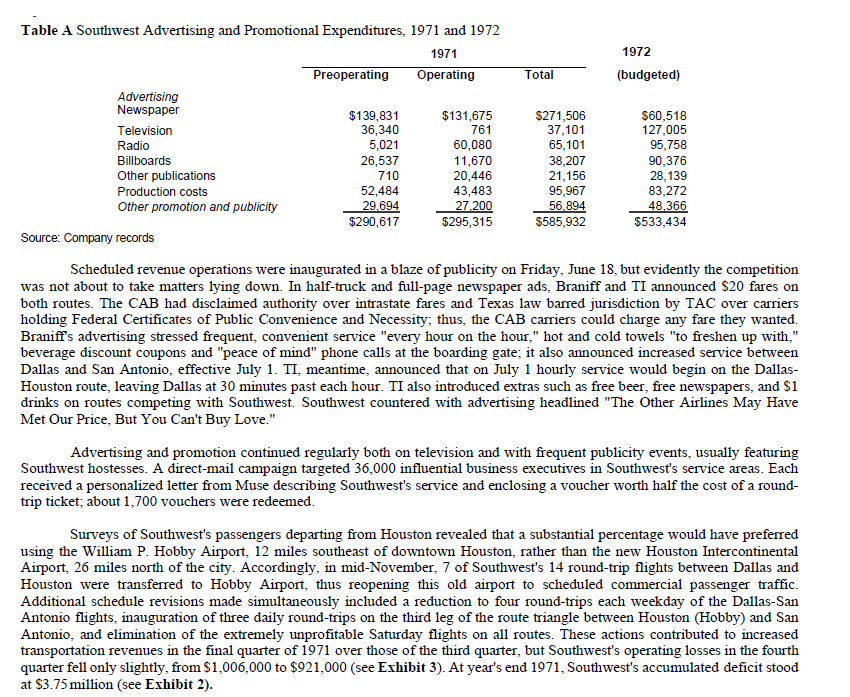

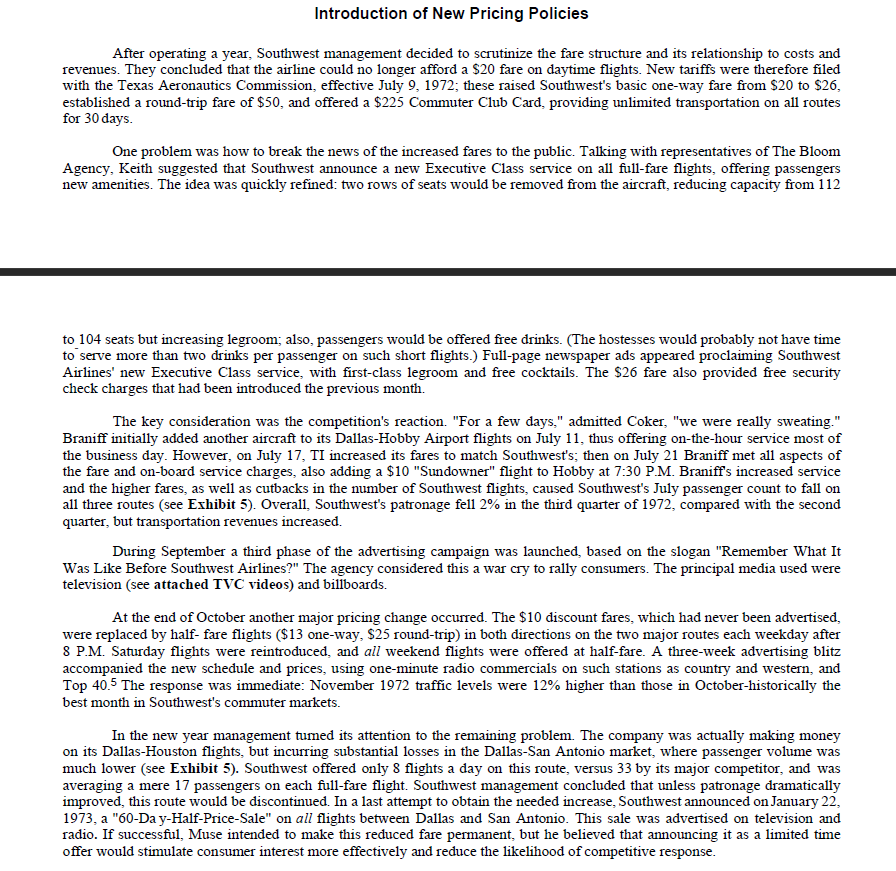

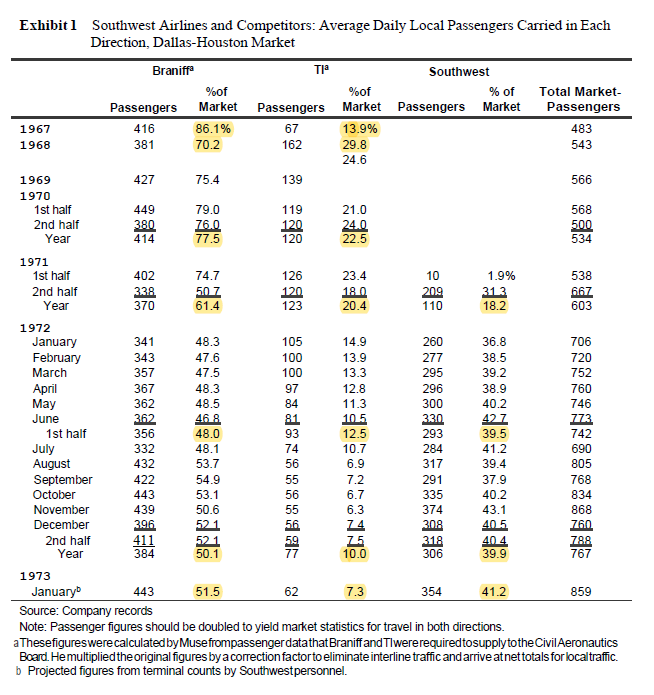

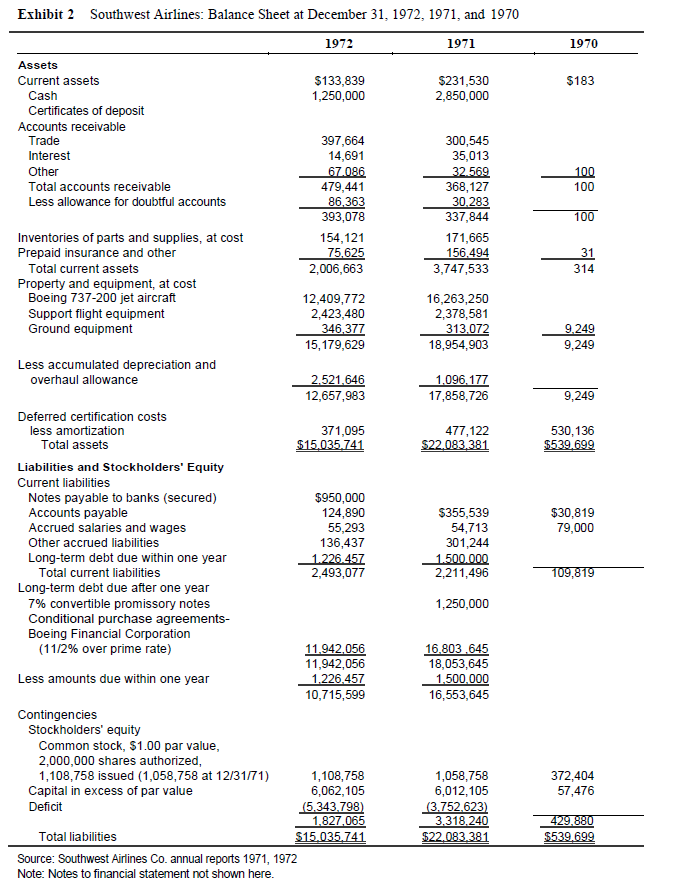

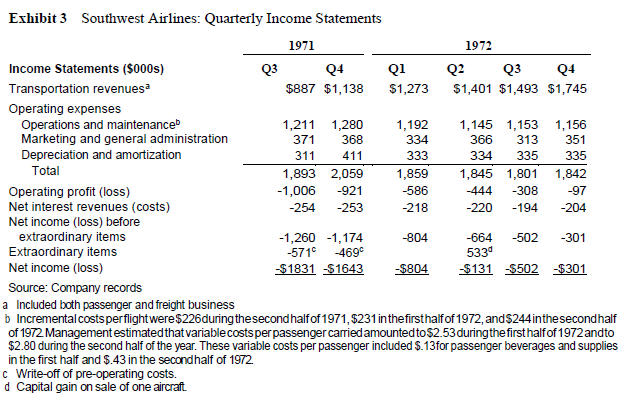

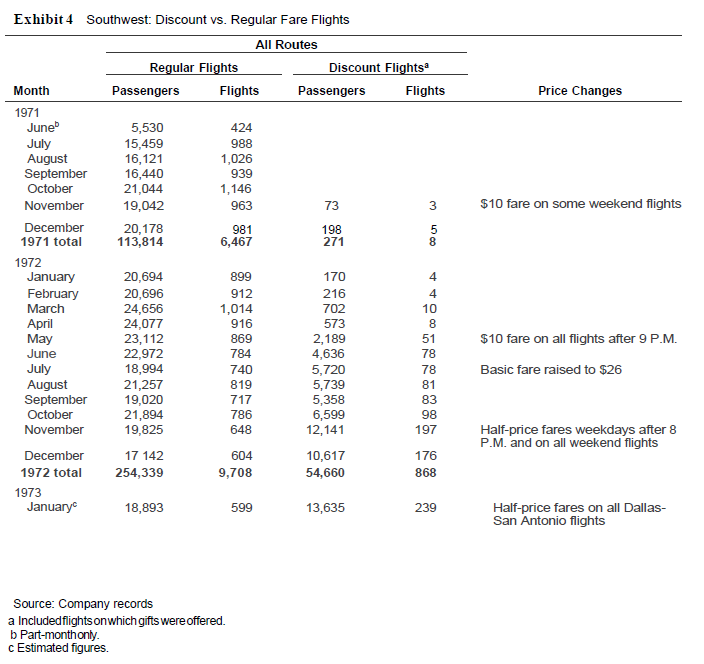

Table A Southwest Advertising and Promotional Expenditures, 1971 and 1972 1971 1972 Preoperating Operating Total (budgeted) Advertising Newspaper $139,831 $131,675 $271,506 $60,518 Television 36,340 761 37,101 127,005 Radio 5,021 60,080 65,101 95,758 Billboards 26,537 11,670 38,207 90,376 Other publications 710 20,446 21,156 28, 139 Production costs 52,484 43,483 95,967 83,272 Other promotion and publicity 29.694 27.200 56.894 48,366 $290,617 $295,315 $585,932 $533,434 Source: Company records Scheduled revenue operations were inaugurated in a blaze of publicity on Friday, June 18, but evidently the competition was not about to take matters lying down. In half-truck and full-page newspaper ads, Braniff and TI announced $20 fares on both routes. The CAB had disclaimed authority over intrastate fares and Texas law barred jurisdiction by TAC over carriers holding Federal Certificates of Public Convenience and Necessity; thus, the CAB carriers could charge any fare they wanted. Braniff's advertising stressed frequent, convenient service "every hour on the hour," hot and cold towels "to freshen up with." beverage discount coupons and "peace of mind" phone calls at the boarding gate; it also announced increased service between Dallas and San Antonio, effective July 1. TI, meantime, announced that on July 1 hourly service would begin on the Dallas- Houston route, leaving Dallas at 30 minutes past each hour. TI also introduced extras such as free beer, free newspapers, and $1 drinks on routes competing with Southwest. Southwest countered with advertising headlined "The Other Airlines May Have Met Our Price, But You Can't Buy Love." Advertising and promotion continued regularly both on television and with frequent publicity events, usually featuring Southwest hostesses. A direct-mail campaign targeted 36,000 influential business executives in Southwest's service areas. Each received a personalized letter from Muse describing Southwest's service and enclosing a voucher worth half the cost of a round- trip ticket; about 1,700 vouchers were redeemed. Surveys of Southwest's passengers departing from Houston revealed that a substantial percentage would have preferred using the William P. Hobby Airport, 12 miles southeast of downtown Houston, rather than the new Houston Intercontinental Airport, 26 miles north of the city. Accordingly, in mid-November, 7 of Southwest's 14 round-trip flights between Dallas and Houston were transferred to Hobby Airport, thus reopening this old airport to scheduled commercial passenger traffic. Additional schedule revisions made simultaneously included a reduction to four round-trips each weekday of the Dallas-San Antonio flights, inauguration of three daily round-trips on the third leg of the route triangle between Houston (Hobby) and San Antonio, and elimination of the extremely unprofitable Saturday flights on all routes. These actions contributed to increased transportation revenues in the final quarter of 1971 over those of the third quarter, but Southwest's operating losses in the fourth quarter fell only slightly, from $1,006,000 to $921,000 (see Exhibit 3). At year's end 1971, Southwest's accumulated deficit stood at $3.75 million (see Exhibit 2).Introduction of New Pricing Policies After operating a year, Southwest management decided to sa'utinize the fare structure and its relationship to costs and revenues. They concluded that the airline could no longer afford a $20 fare on daytime ights. New tariffs were therefore led with the Texas Aeronautics Commission, effective July 9, 1972; these raised Southwest's basic oneway fare from $20 to $26, established a roundtrip fare of $50, and offered a $225 Commuter Club Card, providing unlimited transportation on all routes for 30 days. One problemwas how to break the news of the increased fares to the public. Talking with representatives of The Bloom Agency, Keith suggested that Southwest announce a new Executive Class service on all full-fare ights, offering passengers new amenities. The idea was quickly refined: two rows of seats would be removed from the aircraft, reducing capacity from 112 to 1-34 seats but increasing legroom; also, passengers would be offered free drinks. (The hostesses would probably not have time to'serve more than two drinks per passenger on such short ights.) Fullpage newspaper ads appeared proclaiming Southwest Airlines' new Executive Class service, with rstclass legroom and free cocktails. The $26 fare also provided free security check charges that had been introduced the previous month. The key consideration was the competition's reaction. "For a few days," admitted Coker, "we were really sweating." Brani' initially added another aircraft to its Dallas-Hobby Airport ights on July 1], thus offering onthehour service most of the business day. However, on July 13', '1'] increased its fares to match Southwest's; then on July 21 Brani' met all aspects of the fare and on-b-oard service charges, also adding a $10 "Sundowner" ight to Hobby at 7:30 RM. Brani's increased service and the higher fares, as well as cutbacks in the number of Southwest ights, caused Southwest's July passenger count to fall on all three routes (see Exhibit 5]. Overall, Southwest's patronage fell 2% in the third quarter of 1972, compared with the second quarter, but transportation revenues increased. During September a third phase of the advertising campaign was launched, based on the slogan "Remember What It Was Like Before Southwest Airlines?" The agency considered this a war cry to rally consumers. The principal media used were television (see attached TVC videos) and billboards. At the end of October another major pricing change occurred. The $10 discount fares, which had neverbeen advertised, were replaced by half- fare ights ($13 one-way, $25 round-trip) in both directions on the two major routes each weekday after 8 RM. Saturday ights were reintroduced, and all weekend ights were offered at halffare. A threeweek advertising blitz accompanied the new schedule and prices, using one-minute radio commercials on such stations as country and western, and Top 40.5 The response was immediate: November 19?? trafc levels were 12% higher than those in Octoberhistorically the best month in Southwest's commuter markets. In the new year management turned its attention to the remaining problem The company was actually making money on its Dallas-Houston ights, but incurring substantial losses in the Dallas-San Antonio marlcet, where passenger volume was much lower (see Exhibit 5]. Southwest offered only 8 ights a day on this route, versus 33 by its major competitor, and was averaging a mere 1? passengers on each full-fare ight. Southwest management concluded that unless patronage dramatically improved, this route would be discontinued. In a last attempt to obtain the needed inn-ease, Southwest announced onJanuary 22, 19'1'3, a "ll-Da yHalf-Price-Sale" on all ights between Dallas and San Antonio. This sale was advertised on television and radio. [f successil, Muse intended to make this reduced fare permanent, but he believed that announcing it as a limited time ohr would stimulate consumer interest more effectively and reduce the likelihood of competitive response. Exhibit ] Southwest Airlines and Competitors: Average Daily Local Passengers Carried in Each Direction, Dallas-Houston Market Braniffa Tla Southwest %of %of % of Total Market- Passengers Market Passengers Market Passengers Market Passengers 1967 416 86.1% 67 13.9% 183 1968 381 70.2 162 29.8 543 24.6 1969 427 75.4 139 566 1970 1st half 449 79.0 119 21.0 568 2nd half 380 76.0 120 24.0 500 Year 414 77.5 120 22.5 534 1971 1st half 402 74.7 126 23.4 10 1.9% 538 2nd half 338 50 7 120 180 209 31 3 567 Year $70 61.4 123 20.4 110 18.2 603 1972 January 341 48.3 105 14.9 260 36.8 706 February 343 47.6 100 13.9 277 38.5 720 March 357 47.5 100 13.3 295 39.2 752 April 367 48.3 97 12.8 296 38.9 760 May 362 48.5 84 11.3 300 40.2 746 June 362 46 8 81 10 5 330 42 7 773 1st half 356 48.0 93 12.5 293 39.5 742 July 332 48.1 74 10.7 284 41.2 690 August 432 53.7 56 6.9 317 39.4 805 September 422 54.9 55 7.2 291 37.9 768 October 443 53.1 56 6.7 335 40.2 834 November 439 50.6 55 6.3 374 43.1 868 December 396 52 1 56 74 308 40 5 760 2nd half 411 52 1 59 75 318 40 4 788 Year 384 50.1 77 10.0 306 39.9 767 1973 January 443 51.5 62 7.3 354 41.2 359 Source: Company records Note: Passenger figures should be doubled to yield market statistics for travel in both directions. a Thesefigureswere calculated by Muse frompassenger data that Braniff and TIwere required tosupply to the Civil Aeronautics Board. He multiplied the original figures by a correction factor to eliminate interline traffic and arrive at net totals for local traffic. b Projected figures from terminal counts by Southwestpersonnel.Exhibit 2 Southwest Airlines: Balance Sheet at December 31, 1972, 1971, and 1970 1972 1971 1970 Assets Current assets $133,839 $231,530 $183 Cash 1,250,000 2,850,000 Certificates of deposit Accounts receivable Trade 397,664 300,545 Interest 14,691 35,013 Other 67.086 32.569 100 Total accounts receivable 479,441 368,127 100 Less allowance for doubtful accounts 86,363 30,283 393,078 337,844 100 Inventories of parts and supplies, at cost 154, 121 171,665 Prepaid insurance and other 75,625 156.494 31 Total current assets 2,006,663 3,747,533 314 Property and equipment, at cost Boeing 737-200 jet aircraft 12,409,772 16,263,250 Support flight equipment 2,423,480 2,378,581 Ground equipment 346,377 313.072 9.249 15, 179,629 18,954,903 9,249 Less accumulated depreciation and overhaul allowance 2.521.646 1.096.177 12,657,983 17,858,726 9,249 Deferred certification costs less amortization 371,095 477,122 530,136 Total assets $15.035.741 $22.083,381 6539,699 Liabilities and Stockholders' Equity Current liabilities Notes payable to banks (secured) $950,000 Accounts payable 124,890 $355.539 $30,819 Accrued salaries and wages 55,293 54,713 79,000 Other accrued liabilities 136,437 301,244 Long-term debt due within one year 1.226.457 1.500.000 Total current liabilities 2,493,077 2,211,496 109,819 Long-term debt due after one year 7% convertible promissory notes 1,250,000 Conditional purchase agreements- Boeing Financial Corporation (11/2% over prime rate) 11,942,056 16,803 .645 11,942,056 18,053,645 Less amounts due within one year 1.226.457 1,500.000 10,715,599 16,553,645 Contingencies Stockholders' equity Common stock, $1.00 par value, 2,000,000 shares authorized, 1,108,758 issued (1,058,758 at 12/31/71) 1,108,758 1,058,758 372,404 Capital in excess of par value 6,062, 105 6,012, 105 57,476 Deficit (5.343.798) (3.752.623) 1.827.065 3.318.240 429.880 Total liabilities $15.035,741 $22.083.381 $539.699 Source: Southwest Airlines Co. annual reports 1971, 1972 Note: Notes to financial statement not shown here.Exhibit 3 Southwest Airlines: Quarterly Income Statements 1971 1971 Income Statements ($000s) Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Transportation revenues $887 $1,138 $1,273 $1,401 $1,493 $1,745 Operating expenses Operations and maintenance 1,211 1,280 1,192 1, 145 1,153 1,156 Marketing and general administration 371 368 334 366 313 351 Depreciation and amortization 311 411 333 334 335 335 Total 1,893 2,059 1,859 1,845 1,801 1,842 Operating profit (loss) -1,006 -921 -586 -444 -308 -97 Net interest revenues (costs) -254 -253 -218 -220 -194 -204 Net income (loss) before extraordinary items -1,260 -1,174 -804 -664 -502 -301 Extraordinary items -5710 -469 5330 Net income (loss) -$1831 -$1643 -$804 -$131 : -$502 -$301 Source: Company records a Included both passenger and freight business b Incremental costs perflight were $226during the secondhalf of 1971, $231 in the firsthalf of 1972, and$244 inthe second half of 1972 Management estimated that variable costs per passenger carried amounted to$2.53 during the first half of 1972 andto $2.80 during the second half of the year. These variable costs per passenger included $.13for passenger beverages and supplies in the first half and $.43 in the secondhalf of 1972. c Write-off of pre-operating costs. d Capital gain on sale of one aircraft.Exhibit 4 Southwest: Discount vs. Regular Fare Flights All Routes Regular Flights Discount Flights Month Passengers Flights Passengers Flights Price Changes 1971 June 5,530 424 July 15,459 988 August 16,121 1,026 September 16,440 939 October 21,044 1,146 November 19,042 963 73 $10 fare on some weekend flights December 20,178 981 198 1971 total 113,814 6,467 271 1972 January 20,694 899 170 4 February 20,696 912 216 4 March 24,656 1,014 702 10 April 24,077 916 573 8 May 23,112 869 2,189 51 $10 fare on all flights after 9 P.M. June 22,972 784 4,636 78 July 18,994 740 5,720 78 Basic fare raised to $26 August 21,257 819 5,739 81 September 19,020 717 5,358 83 October 21,894 786 6,599 98 November 19,825 648 12,141 197 Half-price fares weekdays after 8 P.M. and on all weekend flights December 17 142 604 10,617 176 1972 total 254,339 9,708 54,660 868 1973 January 18,893 599 13,635 239 Half-price fares on all Dallas- San Antonio flights Source: Company records a Includedflights on which gifts were offered. b Part-monthonly. C Estimated figures