Question: The discussion will focus on management decision-making and control in two companies, American corporation Amazon.com, Inc. and Chinese company Alibaba Group Holding Limited. Decision-making and

The discussion will focus on management decision-making and control in two companies, American corporation Amazon.com, Inc. and Chinese company Alibaba Group Holding Limited.

Decision-making and control are two vital, and often interlinked, functions of international management. Strategic evaluation and control are the processes of determining the effectiveness of a given strategy in achieving the organizational objectives and taking corrective actions whenever required. Control can be exercised through formulation of contingency strategies and a crisis management team.

For your discussion, use the Decision-Making Process (stages 1-9) outlined in the textbook (Fig 11-1) and this Module's content. Visit the corporate websites of two companies, Amazonand Alibaba, and examine what these firms are doing relating to the strategic evaluation and control process definition in the process above.

For example:

- Stage 1: What is one problem perception for each company?

- Stage 2: What is the problem identification for each company?

- Repeat for stages 3-9.

What overall assumptions can you make using this decision-making process?

supporting citations along with 3 scholarly peer-reviewed references supporting your answer.

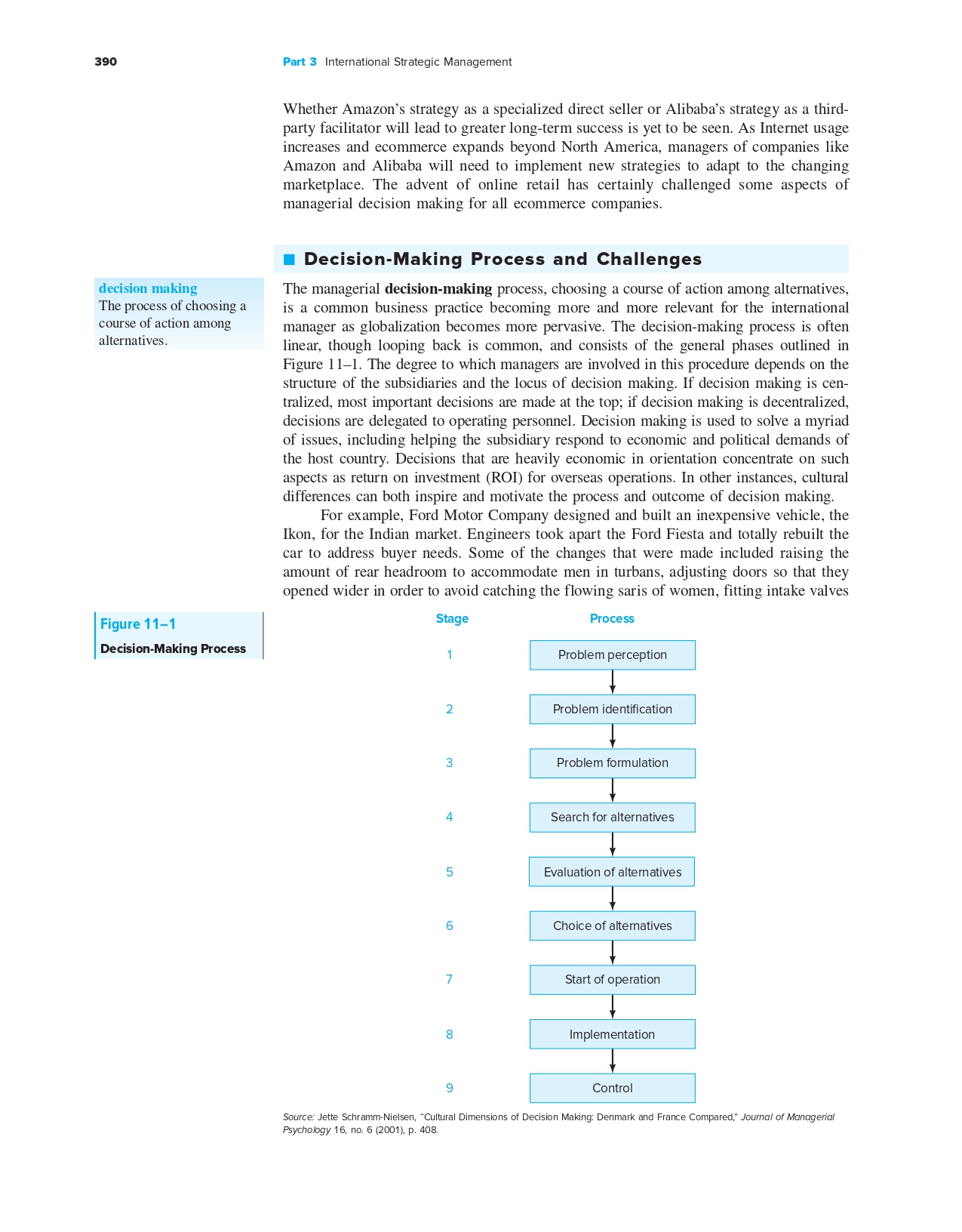

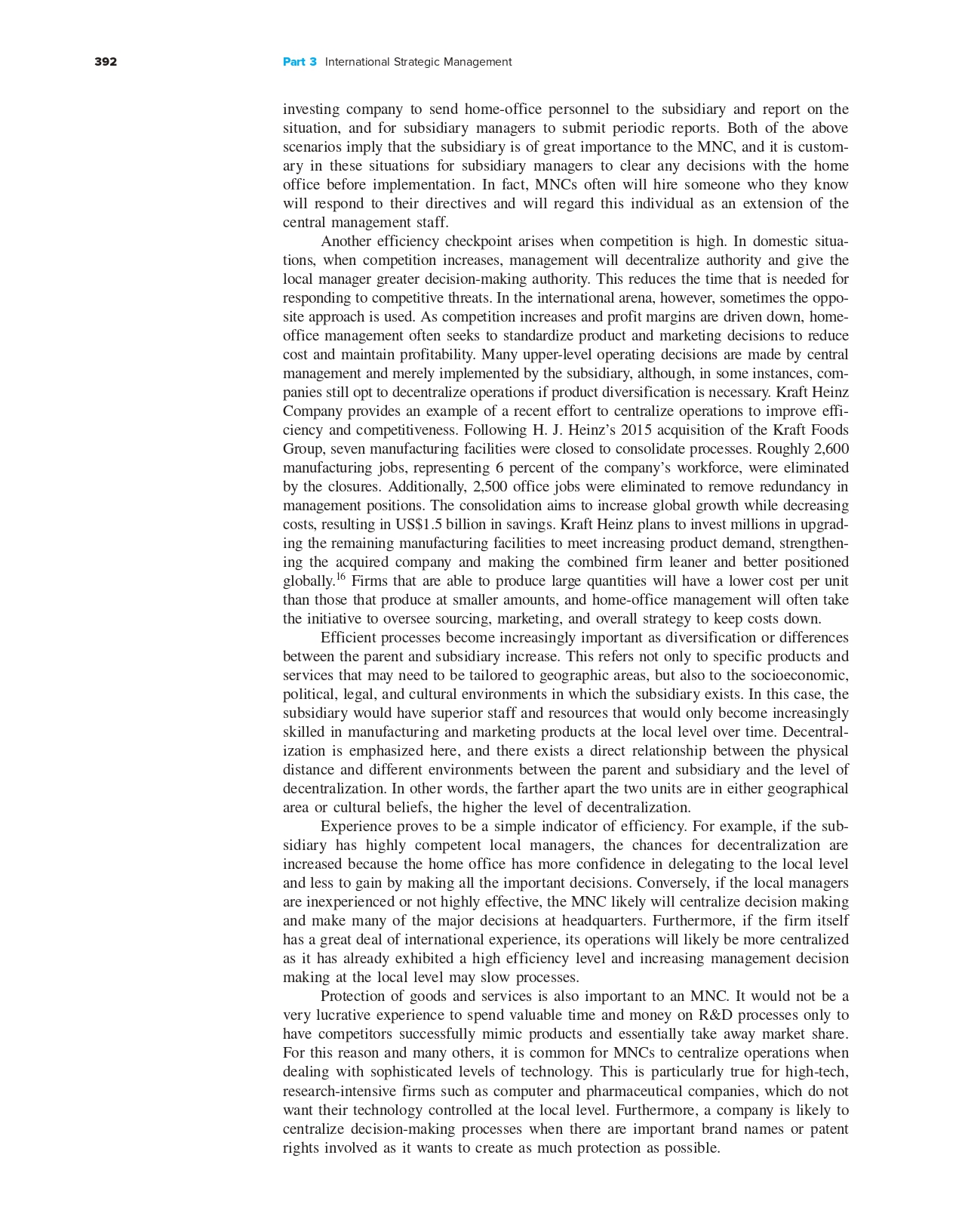

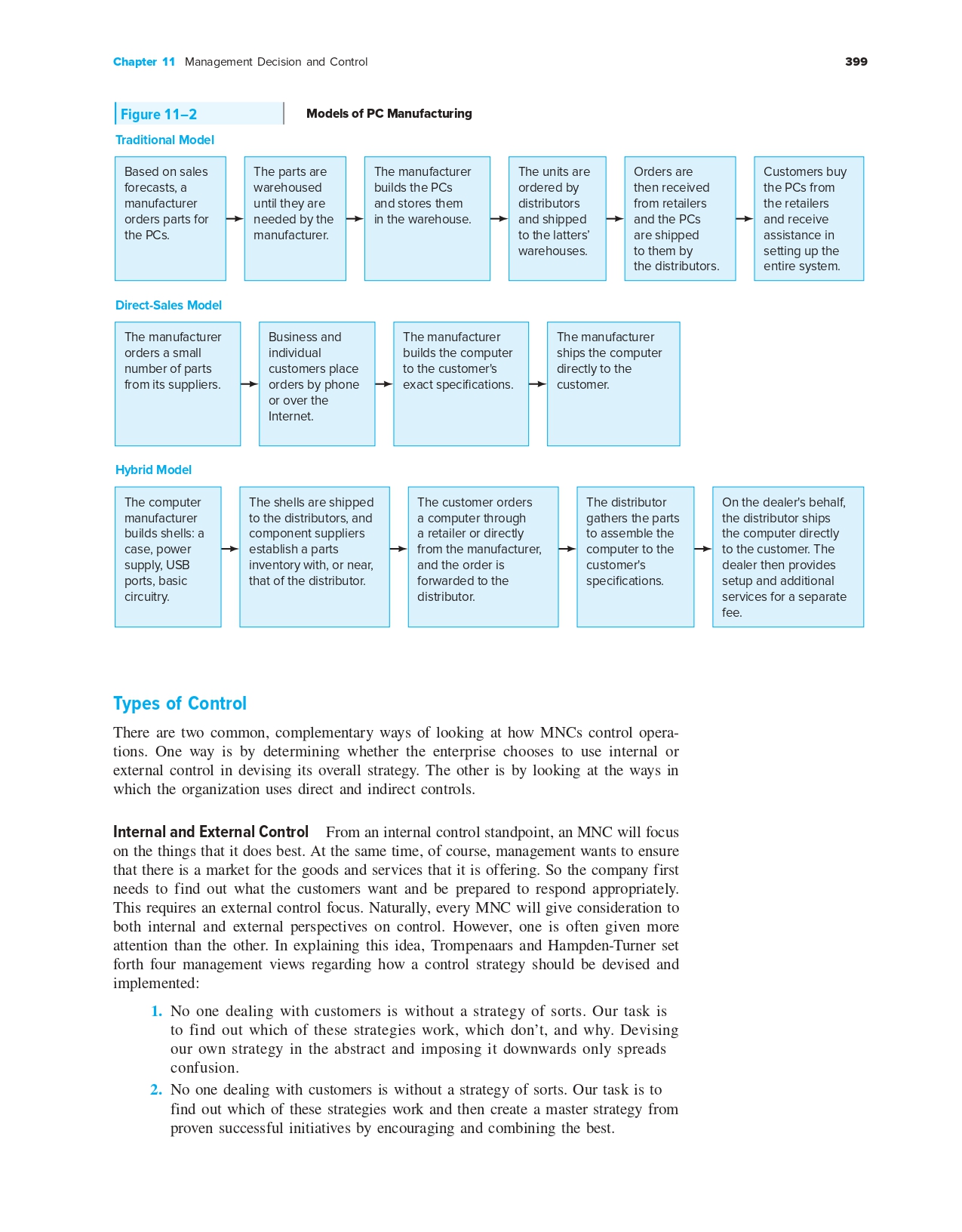

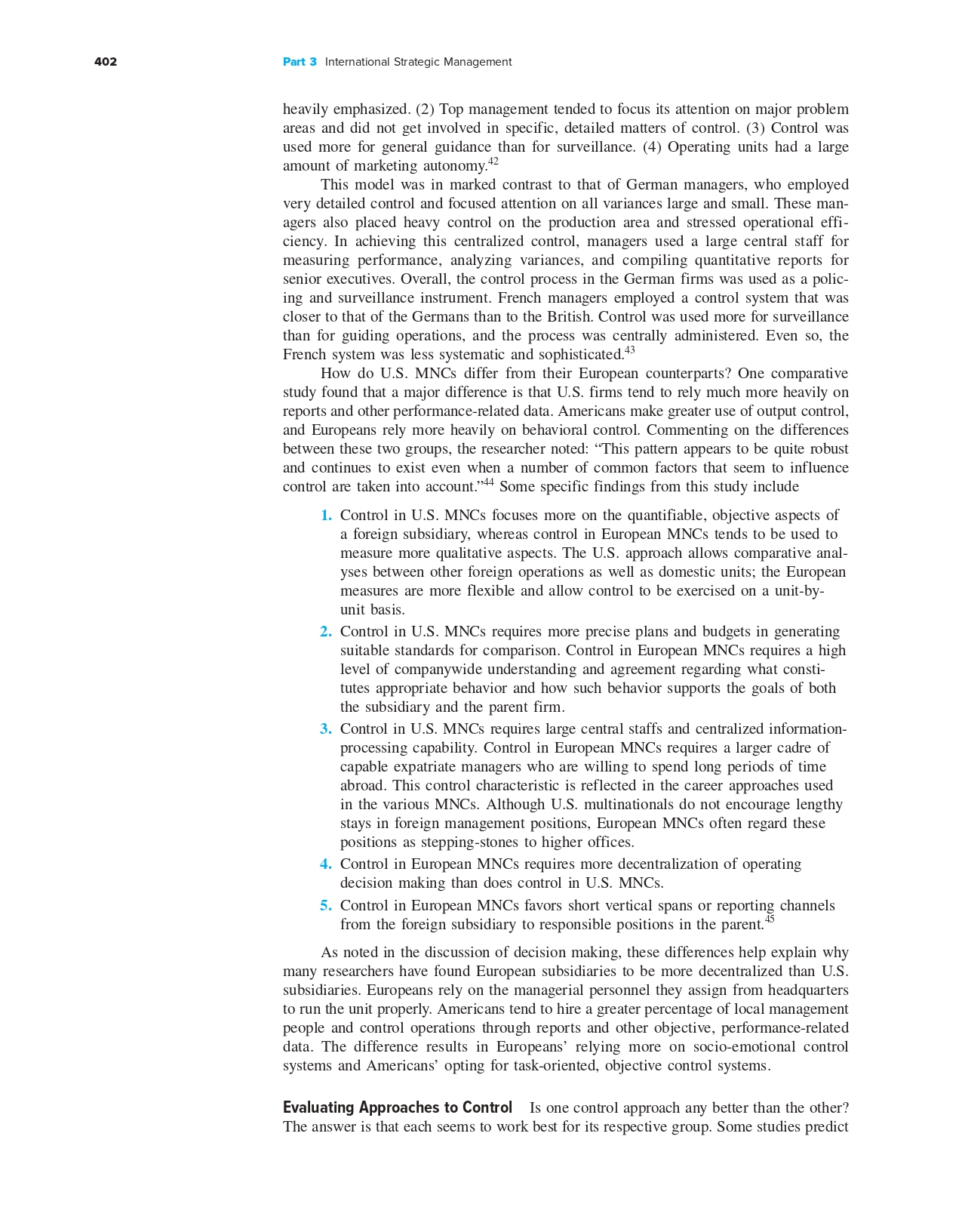

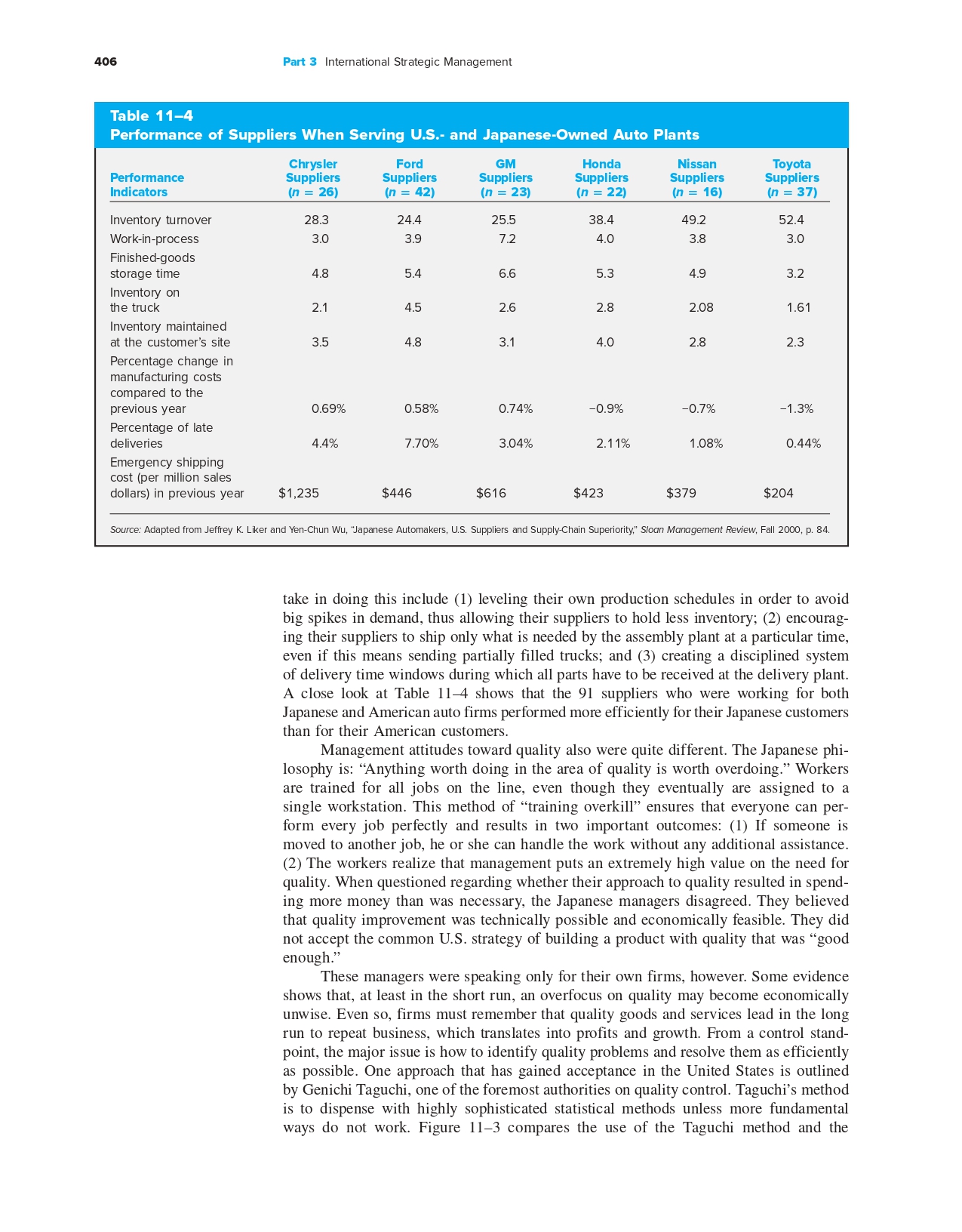

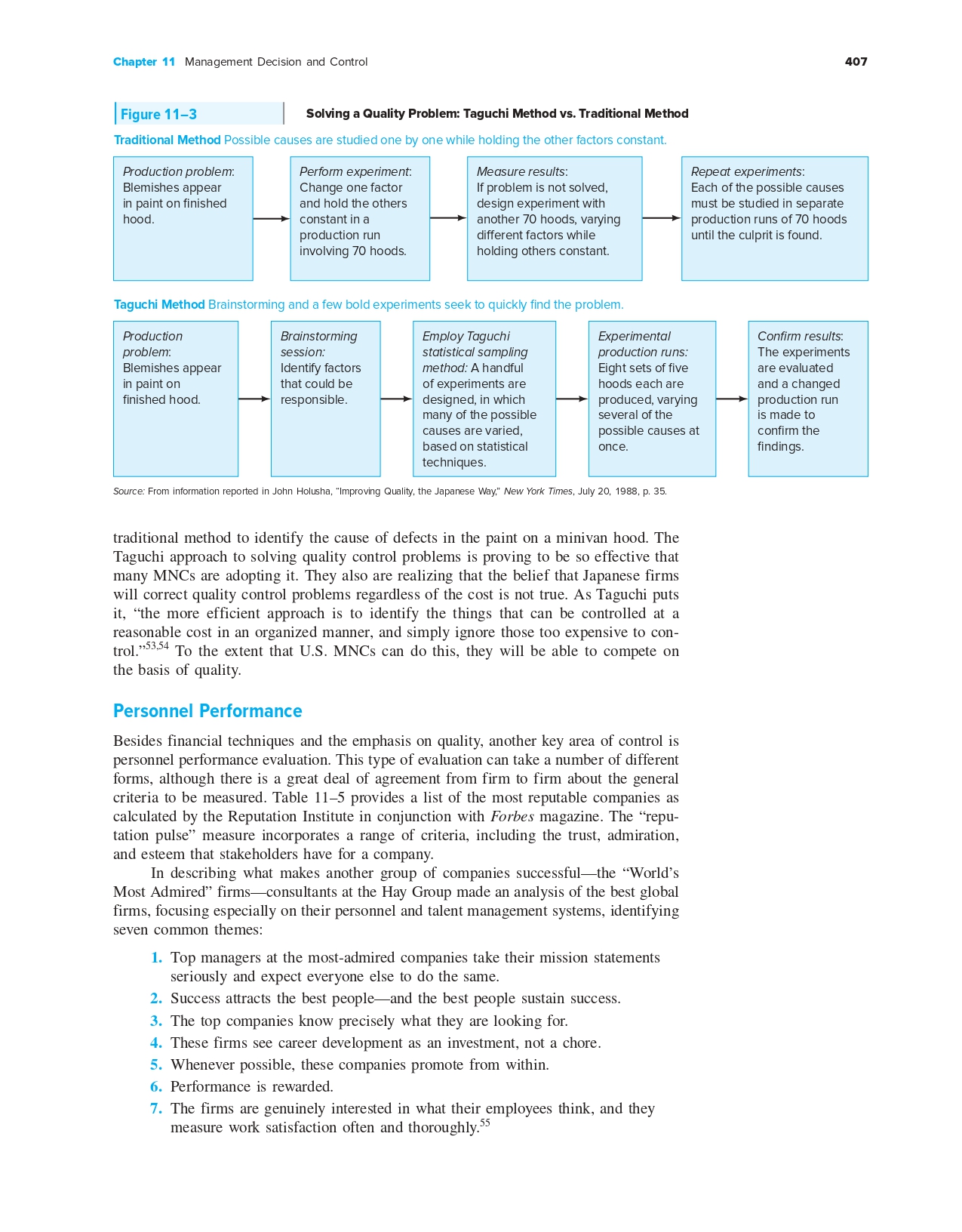

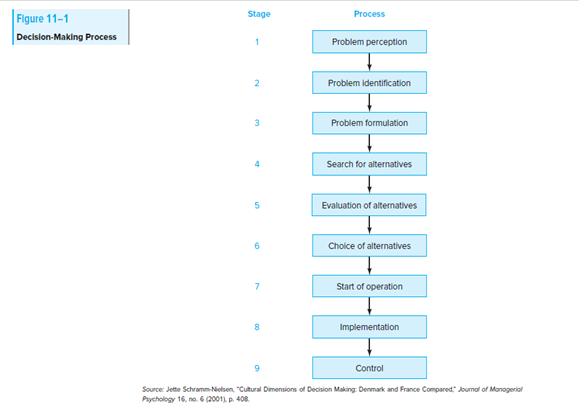

OBJECTIVES OF THE CHAPTER 'I_-Chapter 1 1 MANAGEMENT DECISION AND CONTROL Although they are not directly related to internationalization, decision making and control are two management functions that play critical roles in international operations. In decision making, a manager chooses a course of action among alter- natives. In controiiing, the manager evaluates results in rela- tion to plans or objectives and decides what action, if any, to take. How these functions are carried out is influenced by the international context. An organization can employ a central- ized or decentralized management system depending on such factors as company philosophy or competition. The company also has an array of measures and tools it can use to evalu- ate firm performance and restructuring options. As with most international operations, culture plays a significant role in what is important in both decisionmaking processes and control features, and can affect MNC decisions when forming relationships with subsidiaries. This chapter examines the different decision-making and controlling management functions used by MNCs, notes some of the major factors that account for differences between these functions, and identifies the major challenges of the years ahead. The specific objectives of this chapter are 1. PROVIDE comparative examples of decision making in dif- ferent countries. 2. PRESENT some of the major factors affectingthe degree of decision-making authority given to overseas units. 3. COMPARE and CONTRAST direct controls with indirect controls. 4. DESCRIBE some of the major differences in the ways that MNCs control operations. 5. DISCUSS some of the specific performance measures that are used to control international operations. The World of International Management Global Online Retail: Amazon v. Alibaba ver the last two decades, the Internet has revolution- 0 ized the way customers around the world shop. Accord- ing to Forrester Research, US. online retail sales alone will reach $523 billion by 2020.1 Within the U.S., no online mer- chant has had more success than Amazon. Started in 1995 as a small bookseller, the ecommerce website now sells a vari- ety of products to individuals across North America. While the U.S. has traditionally been the leader in ecommerce, online retail in countries around the world has been growing at a rapid pace. Perhaps most surprising is the sudden surge of the Alibaba Group. an online Chinese retail conglomerate. Consisting of multiple ecommerce-related websites, the Alibaba Group's combined US$462 billion in transactions in 2015 totaled more than eBay and Amazon combined.2 And Alibaba's Tmall, the direct competitor to Amazon, is expected to become the largest individual ecommerce site within the decade, surpassing Amazon in total revenue. Despite similar successes in the ecommerce marketplace, managers at Amazon and Alibaba have taken different approaches to the marketplace. What competitive strategies do these two companies use, and which company stands a better shot at longterm success? Conglomerate versus Specializer The Alibaba Group is a conglomerate of over a half-dozen individual ecommerce websites, combining business-to- business, business-to-consumer, and consumer-to-consumer transactions under a single ownership umbrella. Through its diverse set of websites, the company can cater to virtually any type of transaction, whether it is a small personal pur- chase or a multi-million-dollar business transaction. In addi- tion to providing traditional ecommerce services, the Alibaba Group has branched into web-based business solutions. Uti- lizing its existing infrastructure, Alibaba provides cloud com- puting and data services to companies of all sizes and has even created its own mobile operating system. Alibaba also operates Alipay, a secure payment transfer service, giving the company control over the entire purchase process. Alipay is now used for over half of all online purchases in the country.3 Together, the Alibaba Group conglomerate now accounts for 60 percent of all packages shipped within China and 80 percent of all online sales.'l-5 Amazon, unlike Alibaba, specializes primarily in just busi ness-to-consumer sales. As a result, Amazon's target market is significantly smaller, but more loyal, than Alibaba's. With a pri- mary focus on personal purchases, Amazon has grown into the world's largest online retailer. Recently, however, Amazon has made an effort to expand its offerings. Utilizing the information infrastructure that it established for its traditional business operations, Amazon now offers video streaming, cloud stor- age, and other web services. And in an attempt to enter the growing tablet market, Amazon released its Kindle Fire. It's seventh edition of the Fire, released in late 2015, retails for under US$50, making it one of the most affordable tablets on the market. The core of Amazon's revenue, however, is still generated from its specialization in business-to-consumer transactions.6'T Merchant versus Facilitator Amazon not only hosts third-party sellers, but the company also acts as a direct merchant itself. Amazon buys and sells merchandise, ships products, and warehouses inventory. The company currently has over 100 distribution centers strategi- cally spread across the United States, with roughly one million square feet of storage space per center. This direct- seller approach allows Amazon to quickly adapt to changes in demand. The company can directly control the timeliness and quality of most products sold over its interface, giving it the ability to provide unmatched service features, like single- day delivery. By 2016, over 30 percent of the general US. population and more than 50 percent of its frequent custom- ers were located with 20 miles of an Amazon warehouses Furthermore, by hosting third-party merchants, Amazon is able to generate additional revenue on products sold by its users. However, Amazon's merchant strategy, requiring a large investment in fixed assets, has resulted in minimal prof its for the company. Though it does not have quite the level of expenses that traditional physical stores have, Amazon's margin is tightened by the other necessary investments, like labor and warehouses.9 Alibaba, on the other hand, acts solely as a facilitator for sales between third parties. The company does not carry an inventory, directly sell products, or control distribution. Rather, it simply provides a digital space for those activities to hap- pen. As a result, fixed assets are kept to a minimum. Going forward, the Alibaba Group sees this "efficiency\" as a key business strength. While Amazon's scale of operations is capi- tal intensive, Alibaba's approach allows for extra financial flex- ibility, as it does not need to build, staff, and maintain regional warehouses. One major downside, however, is that Alibaba gives up control over the shipping and distribution operations of its merchants, meaning that mistakes by third-party busi- nesses could reflect negatively on the company as a whole. Furthermore, the company misses out on possible financial gains from direct-to-consumer selling.'F0 Growth Potential Although both companies are online, and therefore \"global,\" the geographic positioning of Amazon and Alibaba affects their potential future growth. Amazon, founded nearly 20 years ago, grew into the largest online retailer in the world due to its geographic advantages. The North American ecommerce mar- ket currently accounts for over 30 percent of all global online sales, and this region is ovemhelmingly dominated by Amazon. In fact, Alibaba has not even attempted to enter the North American marketplace due to Amazon's strength. Although Amazon will likely continue to lead business-to- consumer sales in North America, the future growth potential of Amazon is somewhat limited. North America has nearly 90 percent lntemet penetration, and the population growth of the region has rapidly slowed. In 2014, online sales totals in Asia-Pacific surpassed North American for the first time. In the coming years, North America's share of global ecommerce will decrease to around 25 percent while Asia-Pacific's share will increase to nearly 40 percent.11 Unless Amazon actively expands into other regions across the globe, its revenues will likely stagnate.12 Alibaba's foothold in Asia holds far more growth potential. Internet penetration in China currently stands at just 50 percent, leaving plenty of room for growth with unreach ed customers. Furthermore, nearly 40 percent of the world's population resides in Asia, and the population growth rates within Southeast Asia far exceed those of North America. As wealth continues to accumulate in the region, Internet access and ecommerce will likely expand. If the Alibaba Group can maintain its strong standing in Asia, revenue will grow significantly over the next decade.13 390 decision making The process of choosing a course of action among alternatives. Figure 1 11 Decision-Making Process Part 3 International Strategic Management Whether Amazon's strategy as a specialized direct seller or Alibaba's strategy as a third- party facilitator will lead to greater long-term success is yet to be seen. As Internet usage increases and ecommerce expands beyond North America, managers of companies like Amazon and Alibaba will need to implement new strategies to adapt to the changing marketplace. The advent of online retail has certainly challenged some aspects of managerial decision making for al] ecommerce companies. I Decision-Making Process and Challenges The managerial decision-making process, choosing a course of action among alternatives, is a common business practice becoming more and more relevant for the international manager as globalization becomes more pervasive. The decision-making process is often linear, though looping back is common, and consists of the general phases outlined in Figure 111. The degree to which managers are involved in this procedure depends on the structure of the subsidiaries and the locus of decision making. If decision making is cen- tralized, most important decisions are made at the top; if decision making is decentralized, decisions are delegated to operating personnel. Decision making is used to solve a myriad of issues, including helping the subsidiary respond to economic and political demands of the host country. Decisions that are heavily economic in orientation concentrate on such aspects as return on investment (ROI) for overseas operations. In other instances, cultural differences can both inspire and motivate the process and outcome of decision making. For example, Ford Motor Company designed and built an inexpensive vehicle, the lkon, for the Indian market. Engineers took apart the Ford Fiesta and totally rebuilt the car to address buyer needs. Some of the changes that were made included raising the amount of rear headroom to accommodate men in turbans, adjusting doors so that they opened wider in order to avoid catching the owing saris of women, fitting intake valves Stage Process 1 Problem perception f 2 Problem identification _l_ 3 Problem formulation _; 4 Search for alternatives f 5 Evaluation of alternatives l 6 Choice of alternatives _l_ 7 Start of operation f 8 Implementation f 9 Control Source: Jette SchramrnNielsen, "Cultural Dimensions of Decision Making: Denmark and France Compared," JournalI a! Managerial Psymoiogy 1 6. no. 6 (2001). p. 408. Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control to avoid auto flooding during the monsoon season, toughening shock absorbers to handle the pockmarked city streets, and adjusting the air-conditioning system to deal with the intense summer heat.14 As a result of these decisions, the car sold very well in India. Ford replicated that same strategy with the lkon's successor, the Fiesta Mark VI. Santander, the largest bank in Europe by market capitalization, is vesting more autonomy in its subsidiaries by listing subsidiaries in its principal foreign markets and thereby strengthening their independence and autonomy from the Spanish headquarters. A num- ber of European banks, including Santander and HSBC Holdings PLC (see In-Depth Integrative Case 4.1 at the end of Part Four), establish foreign subsidiaries as opposed to direct branches. Santander Chief Executive Ofcer Alfredo Saenz said, \"We also believe it's good for the local management teams, because having local minority share- holders breathing down their neck keeps them on their toes, and it's a good way of identifying the franchise as local, instead of foreign.\" In addition, the IPO boosted the visibility of the bank in Brazil, resulted in greater access to local capital, and put a higher value on the franchise than what analysts were giving it before the oat. When Santander sold 15 percent of its Brazilian unit, the unit alone was valued at 34 billion, more than European rivals Deutsche Bank or Socit Gnerale.15 The way in which decision making is carried out will be influenced by a number of factors. We will rst look at some of the factors, then provide some comparative examples in order to illustrate some of the differences. Factors Affecting Decision-Making Authority A number of factors inuence international managers' conclusions about retaining author- ity or delegating decision making to a subsidiary. Table [171 lists some of the most important situational factors, and the following discussion evaluates the inuential aspects. One of the major concerns for organizations is how efcient the processes are that are put in place. The size of a company can have great importance in this realm. Larger organizations may choose to centralize authority for critical decisions in order to ensure efficiency through greater coordination and integration of operations. The same holds true for companies that have a high degree of interdependence because there is a greater need for coordination. This is especially relevant when organizations provide a large investment because they prefer to keep track of progress. It is quite common for the Table 111 Factors That Influence Centralization or Decentralization of Decision Making in Subsidiary Operations Encourage Centralizatien Encourage Decentralization Large size Small size Large capital investment Small capital investment Relatively high importance to MNC Relatively low importance to MNC Highly competitive environment Stable environment Strong volumetounitcost relationship Weak volumetounitcost relationship High degree of technology Moderate to low degree of technology Strong importance attached to brand Little importance attached to brand name, name, patent rights, etc. patent rights, etc. Low level of product diversification High level of product diversification Homogeneous product lines Heterogeneous product lines Small geographic distance between Large geographic distance between home home office and subsidiary ofce and subsidiary High interdependence between the units Low interdependence between the units Fewer highly competent managers More highly competent managers in host in host country country Much experience in international business Little experience in international business 391 Part 3 International Strategic Management investing company to send home-office personnel to the subsidiary and report on the situation, and for subsidiary managers to submit periodic reports. Both of the above scenarios imply that the subsidiary is of great importance to the MNC, and it is custom- ary in these situations for subsidiary managers to clear any decisions with the home office before implementation. In fact, MNCs often will hire someone who they know will respond to their directives and will regard this individual as an extension of the central management staff. Another efficiency checkpoint arises when competition is high. In domestic situa- tions, when competition increases, management will decentralize authority and give the local manager greater decision-making authority. This reduces the time that is needed for responding to competitive threats. In the international arena, however, sometimes the oppo- site approach is used. As competition increases and prot margins are driven down, home- ofce management often seeks to standardize product and marketing decisions to reduce cost and maintain profitability. Many upper-level operating decisions are made by central management and merely implemented by the subsidiary, although, in some instances, com- panies still opt to decentralize operations if product diversication is necessary. Kraft Heinz Company provides an example of a recent effort to centralize operations to improve effi- ciency and competitiveness. Following H. J. Heinz's 2015 acquisition of the Kraft Foods Group, seven manufacturing facilities were closed to consolidate processes. Roughly 2,600 manufacturing jobs, representing 6 percent of the company's workforce, were eliminated by the closures. Additionally, 2,500 ofce jobs were eliminated to remove redundancy in management positions. The consolidation aims to increase global growth while decreasing costs, resulting in US$I.5 billion in savings. Kraft Heinz plans to invest millions in upgrad- ing the remaining manufacturing facilities to meet increasing product demand, strengthen- ing the acquired company and making the combined firm leaner and better positioned globally\"; Firms that are able to produce large quantities will have a lower cost per unit than those that produce at smaller amounts, and home-office management will often take the initiative to oversee sourcing, marketing, and overall strategy to keep costs down. Efficient processes become increasingly important as diversication or differences between the parent and subsidiary increase. This refers not only to specific products and services that may need to be tailored to geographic areas, but also to the socioeconomic, political, legal, and cultural environments in which the subsidiary exists. In this case, the subsidiary would have superior staff and resources that would only become increasingly skilled in manufacturing and marketing products at the local level over time. Decentral- ization is emphasized here, and there exists a direct relationship between the physical distance and different environments between the parent and subsidiary and the level of decentralization. In other words, the farther apart the two units are in either geographical area or cultural beliefs, the higher the level of decentralization. Experience proves to be a simple indicator of efficiency. For example, if the sub- sidiary has highly competent local managers, the chances for decentralization are increased because the home office has more condence in delegating to the local level and less to gain by making all the important decisions. Conversely, if the local managers are inexperienced or not highly effective, the MNC likely will centralize decision making and make many of the major decisions at headquarters. Furthermore, if the firm itself has a great deal of international experience, its operations will likely be more centralized as it has already exhibited a high efficiency level and increasing management decision making at the local level may slow processes. Protection of goods and services is also important to an MNC. It would not be a very lucrative experience to spend valuable time and money on R&D processes only to have competitors successfully mimic products and essentially take away market share. For this reason and many others, it is common for NINCS to centralize operations when dealing with sophisticated levels of technology. This is particularly true for high-tech, research-intensive firms such as computer and pharmaceutical companies, which do not want their technology controlled at the local level. Furthermore, a company is likely to centralize decision-making processes when there are important brand names or patent rights involved as it wants to create as much protection as possible. Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control In some areas of operation, MNCs tend to retain decision making at the top (centralization); other areas fall within the domain of subsidiary management (decentralization). It is most common to find finance, R&D, and strategic planning deci- sions being made at MNC headquarters with the subsidiaries working within the param- eters established by the home office In addition, when the subsidiary is selling new products in growing markets, centralized decision making is more likely. As the product line matures and the subsidiary managers gain experience, however, the company will start to rely more on decentralized decision making. These decisions involve planning and budgeting systems, performance evaluations, assignment of managers to the subsid- iary, and use of coordinating committees to mesh the operations of the subsidiary with the worldwide operations of the MNC. The right degree of centralized or decentralized decision making can be critical to the success of the MNC. Deloitte, the accounting and management consulting firm, describes some of the challenges associated with postmerger integration in the area of centralization and decentralization: The union of two European engineering companies is a prime example of a merger that brought together companies with very different structuresa business unit of a much larger corporation and a standalone company. The business unit had a more decentralized management approach with responsibilities delegated within functional areas such as procurement and IT. In contrast, the standalone company had a more centralized approach with a strong corporate headquarters retaining control over IT, finance, procurement and HR. Bringing these two disparate structures together without reconciling these differences almost destroyed the new company. Sales plum meted and key people left, unable to adjust to the new corporate structure. \"fithitl three years the company collapsed, to be swiftly scooped up by a competitor.'7 Cultural Differences and Comparative Examples of Decision Making Culture, whether outside or within the organization (see Chapters 4 and 6, respectively), has an effect on how individuals and businesses perceive situations and subsequently react. This knowledge raises the question: Do decision-making philosophies and practices differ from country to country? Research shows that to some extent they do, although there also is evidence that many international operations, regardless of foreign or domestic ownership, use similar decision-making norms. One study showed that French and Danish managers do not approach the decision- making process in the same manner.18 The French managers tend to spend ample time on searching for and evaluating alternatives (see Figure 111), exhibiting rationality and intelligence in each option. While the French approach each opportunity with a sense of creativity and logic, they tend to become quite emotionally charged rather quickly if challenged. Middle managers report to higher-level managers, who ultimately make the final decision. Therefore, the individualistic nature of the French creates an environment in which middle managers vie for the recognition and praise of the upper management. Furthermore, middle-management implementation of ideas tends to be lacking because that stage is often seen as boring, practical work that lacks the prestige managers strive to achieve. Control, discussed later in the chapter, is quite high in the French firms at every level, so where implementation fails, control will compensate. Danish managers tend to emphasize different stages in the decision-making process (see Figure 111). They do not spend as much time searchng or analyzing alternatives to optimize production but instead choose the option that can be started and implemented quickly and still bring about the relative desired results. They are less emotionally respon- sive and tend to take a straightforward approach. Danes do not emphasize control in operations because it tends to be a sign that management lacks confidence in the areas that \"require\" high control. The cooperative as opposed to individualistic emphasis in Danish corporations, coupled with a results-oriented environment, breeds a situation in which decisions are made quickly and middle managers are given autonomy. Overall, the pragmatic nature of the Danes and the French need for intellectual prowess mark why each is more adept at different stages of the decision-making process. 393 394 codetermination A legal system that requires workers and their managers to discuss major decisions. ringisei A Japanese term that means \"decision making by consensus.\" tatemae A Japanese term that means \"doing the right thing" according to the norm. honne A Japanese term that means \"what one really wants to do.\" total quality management (TQND An organizational strategy and the accompanying techniques that result in the delivery of highquality products or services to customers. Part 3 International Strategic Management The French tend to be better at stages 4, 5, and 9, while the Danes are more adept at stages 6, 7, and 8 (see Figure 111). As one Danish manager in France says: They Danes and Frenchmen] do not analyze and synthesize the same way. The French tend to think that the Danes are not thorough enough, and the Danes tend to think that the French are too complicated. At his desk, the Frenchman tends to keep on working on the case. He seems to agree neither with his surroundings nor with himself. This means that when he has analyzed a case and has come to a conclusion, then he would like to go over it once more. I think that Frenchmen think in a more synthetic way . . . and he has a tendency to say: \"well, yes, but what if it can still be done in another maybe smarter way." This means that in fact he is wasting time instead of making improvements.'9 In Germany, managers focus more on productivity and quality of goods and ser- vices than on managing subordinates, which often translates into companies pursuing long-term approaches. In addition, management education is highly technical, and a legal system called codeterminaon requires workers and their managers to discuss major decisions. As a result, German MNCs tend to be fairly centralized, autocratic, and hier- archical. Scandinavian countries also have codetermination, but the Swedes focus much more on quality of work life and the importance of the individual in the organization. As a result, decision making in Sweden is decentralized and participative. The Japanese are somewhat different from the Europeans, though they still employ a long-term focus. They make heavy use of a decision-making process called ringisei, or decision making by consensus. Under this system, any changes in procedures and routines, tactics, and even strategies of a firm are organized by those directly concerned with those changes. The final decision is made at the top level after an elaborate exam- ination of the proposal through successively higher levels in the management hierarchy, and results in acceptance or rejection of a decision only through consensus at every echelon of the management structure.20 Sometimes Japanese consensus decision making can be very time-consuming. How- ever, in practice most Japanese managers know how to respond to \"suggestions\" from the top and to act accordinglythus saving a great deal of time. Many outsiders misunder- stand how Japanese managers make such decisions. In Japan, what should be done is called talemae, whereas what one really feels, which may be quite different, is home. Because it is vital to do what others expect in a given context, situations arise that often strike Westerners as a game of charades. Nevertheless, it is very important in Japan to play out the situation according to what each person believes others expect to happen. Another cultural difference is how managers view time in the decision-making process. As we saw from the French-Danish example earlier, the French do not value time as much as their counterparts. The French want to ensure that the best alternative was put into action, whereas the Danes want to act first and take advantage of opportu- nities. This is key in many international decision-making processes, as globalization has opened the door to extreme competition, and all players need to be able to both identify and make the most of profitable prospects. In another study of decision making in teams composed of Swedes, Germans, and combinations of the two, researchers found Swedish teams featured higher team orienta- tion, flatter organizational hierarchies, and more open-minded and informal work atti- tudes. In this study, German team members were perceived to be faster in decision making, to have clearer responsibilities for the individual, and to be more willing to accept a changed or unpopular decision. In Swedish teams, decision making appeared more transparent and less formal. On German teams, the process is largely dominated by the decision authority of an expert in the field. This is in contrast to the group decision-making style used in Swedish teams.21 Total Quality Management Decisions To achieve world-class competitiveness, MNCs are finding that a commitment to total quality management is critical. Total quality management (TQM) is an organizational Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control strategy and accompanying techniques that result in delivery of high-quality products or services to customers.22 The concept and techniques of TQM, which were introduced in Chapter 8 in relation to strategic planning, also are relevant to decision making and controlling. One of the primary areas where TQM is having a big impact is in manufacturing. A number of TQM techniques have been successfully applied to improve the quality of manufactured goods. One is the use of concurrent engineering/interfunctional teams in which designers, engineers, production specialists, and customers work together to develop new products. This approach involves all the necessary parties and overcomes what used to be an all-too-common procedure: The design people would tell the manu- facturing group what to produce, and the latter would send the finished product to retail stores for sale to the customer. Today, MNCs taking a TQM approach are customer- driven. They use TQM techniques to tailor their output to customer needs, and they require the same approach from their own suppliers.23 Recently, Lenovo has transformed its design process from an engineer-driven one to a customer-driven one. In 2016, the company developed and began using an application that pulls together unstructured cus- tomer feedback from a variety of sources, including You'Iube comments, online forums, and traditional call centers, and organizes the data in a useful way so that Lenovo can design tablets and products that best meet consumer demands.\" A particularly critical issue is how much decision making to delegate to subordi- nates. TQM uses employee empowerment. Individuals and teams are encouraged to generate and implement ideas for improving quality and are given the decision-making authority and necessary resources and information to implement them. Many MNCs have had outstanding success with empowerment. For example, General Electric credits employee empowerment for cutting in half the time needed to change product-mix production of its dishwashers in response to market demand. Another TQM technique that is successfully employed by MNCs is rewards and recognition. These range from increases in pay and benets to the use of merit pay, discretionary bonuses, pay-for-skills and knowledge plans, plaques, and public recogni- tion. The important thing to realize is that the rewards and recognition approaches that work well in one country may be ineffective in another. For example, individual recog- nition in the U.S. may be appropriate and valued by workers, but in Japan, group rewards are more appropriate as Japanese do not like to be singled out for personal praise. Similarly, although putting a picture or plaque on the wall to honor an individual is common practice in the United States, these rewards are frowned on in Finland, for they remind the workers that their neighbors, the Russians, used this system to encourage people to increase output (but not necessarily quality), and while the Russian economy is beginning to make headway, it was once in shambles in part due to poor decision making. Still another technique associated with TQM is the use of ongoing training to achieve continual improvement. This training takes a wide variety of forms, ranging from statistical quality control techniques to team meetings designed to generate ideas for streamlining operations and eliminating waste. In all cases, the objective is to apply what the Japanese call kaizen, or continuous improvement. By adopting a TQM perspective and applying the techniques discussed earlier, MNCs find that they can both develop and maintain a worldwide competitive edge. A good example is provided by Herman Miller, the American office furniture company. Herman Miller manufactures some of the best- selling office task chairs worldwide. Over the last 15 years, the company has used the kaizen mindset to improve quality by 1,000 percent and productivity by 500 percent. Originally, it took approximately 82 seconds for Herman Miller to produce a single chair from its production line. Today, it only takes 17 seconds.\" Table \"2 provides some examples of the new thinking that is now emerging regarding quality. Ford Motor Company has been able to thrive in the post-global recession environ- ment due in part to its implementation of kaizen principles. As a former vice president at Boeing, Ford CEO Alan Mulally brought the philosophy with him when he came to empowerment The process of giving individuals and teams the resources, information, and authority they need to develop ideas and effectively implement them. kaizen A Japanese term that means \"continuous improvemen .\" Part 3 International Strategic Management Table 112 The Emergence of New Beliefs Regarding Quality Old Myth New Truth Quality is the responsibility of the people Quality is everyone's job. in the Quality Control Department. Training is costly. Training does not cost: it saves. New quality programs have high initial The best quality programs do not have upfront costs. costs. Better quality will cost the company a lot As quality goes up, cosB come down. of money. The measurement of data should be kept An organization cannot have too much relevant to a minimum. data on hand. It is human to make mistakes. Perfectiontotal customer satisfactionis a standard that should be vigorously pursued. Some defects are major and should be No defects are acceptable, regardless of addressed, but many are minor and can be whether they are major or minor. ignored. Quality improvemenm are made in small, In improving quality, both small and large continuous steps. improvements are necessary. Quality improvement takes time. Quality does not take time; it saves time. Haste makes waste. Thoughtful speed improves quality. Quality programs are best oriented toward Quality is important in all areas, including areas such as products and manufacturing. administration and service. After a number of quality improvements, Customers are able to see all improvements, customers are no longer able to see addi including those in price, delivery, and tional improvements. performance. Good ideas can be found throughout the Good ideas can be found everywhere, includ organization. ing in the operations of competitors and orga nizations providing similar goods and services. Suppliers need to be price competitive. Suppliers need to be quality competitive. Source: Reporled in Richard M. Hodgetts, Measures of mymd High Performance (New 'i'orI-c Arnerimn Management Association, 1998], p. 14. the company in 2006. By focusing on implementing more efcient procedures, Ford was able to create 5,000 new jobs in the United States in 2014.35 Indirectly related to TQM is ISO 9000, International Standards Organization (ISO) certication, to ensure quality products and services. Areas that are examined by the ISO certication team include design (product or service specications), process control (instruction for manufacturing or service functions), purchasing, service (e.g., instruc- tions for conductirlg after-sales service), inspection and testing, and training. ISO 9000 certication is becoming a necessary prerequisite to doing business in the EU, but it also is increasingly used as a screening criterion for bidding on contracts or getting business in the United States and other parts of the world. Decisions for Attacking the Competition Another series of key decisions relates to MNC actions that are designed to attack the competition and gain a foothold in world markets. An example is Ford Motor Company's decision to challenge other automakers, like "Data, and to be a major player in developing markets, such as Asia and Africa. As a result of this decision, Ford has been shifting production closer to the local consumer and away from its stagnant U.S. home market. In 2015, Ford announced plans to open a manufacturing plant for its pickup truck, the Ranger, in Lagos, Nigeria. As Ford's first plant in Africa outside of South Africa, the new Lagos facility aims to provide Ford with the infrastructure and manufacturing Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control capacity necessary for future growth.27 Ford has also opened plants in China and Thailand in recent years, with the ability to produce more than 100,000 vehicles every year for the local Asian market.28 Another example of decision making for attacking the competition is provided by the global luxury car industry. While German automakers Audi, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW all share the same goal of leading the international luxury vehicle market, the companies are taking different approaches to beat the competition. Audi has made the decision to target younger professionals in established markets. This strategy is reflected in the company's new, trendy body designs. Though the demographics of the luxury vehicle market favors older consumers, Audi's approach has been fairly successful. More than 90,000 units are now sold annually in the U.S., vaulting Audi into fourth place in the local market. Conversely, BMW has attempted to undermine the competition by focusing on providing more options and personalization for its consumers. With a variety of engine and body options, the company offers more than 100 different combinations for its luxury vehicles in the U.S. And Mercedes, which holds the largest share of the luxury vehicle market, has taken a lowest-cost strategy. With its CLA 250 starting at under US $30,000, the luxury sedan offers high value for a price that is less than that of the average car sale in the U.S.29 I Decision and Control Linkages Decision making and controlling are two vital and often interlinked functions of inter- national management. As an example of a company that struggled with control issues, Canadian company Blackberry Limited (formerly Research in Motion) ultimately failed in the smartphone industry due to its slow market response. Over the course of just six years, Blackberry evolved from the most promising phone producer to just a footnote. In 2009, Blackberry was one of the fastest-growing companies in the world, with an 84 percent increase in earnings.30 Blackberry held an estimated 4] percent share of the smartphone market in the U.S. by 2010, making it more popular than Apple's iPhone. However, as Apple and Samsung introduced touchscreens and innovated to meet cus- tomer demands, Blackberry continued producing phones with full keyboards. 1n the high- tech sector, where the pace of change is incredibly fast, Blackberry's resistance to meet customer expectations led to a rapid decline in market share. By the time Blackberry nally adapted to the evolving mobile market, it was too late; by 2015, Blackberry's market share dropped to just 1 percent.31'32 Another example of how the control function plays out is Universal Studios Japan. To attract visitors to the Osaka location, this new theme park was specially built based on feedback from Japanese tourists at Universal parks in Orlando and Los Angeles. The company wanted to learn what these visitors liked and disliked and then use this infor- mation in its Osaka park. One theme clearly emerged: The Japanese wanted an authentic American experience but also expected the park to cater to their own cultural preferences. In the process of controlling the creation of the new park, thousands of decisions were made regarding what to include and what to leave out. For example, seafood pizza and gumbo-style soup were put on the menu, but a fried-shrimp concoction with colored rice crackers was rejected. It was decided that in a musical number based on the movie Beetlejm'ce, the main character should talk in Japanese and his Sidekicks would speak and sing in English. The decision to put in a restaurant called Shakin's, based on the [906 San Francisco earthquake, turned out to be not a good idea because Osaka has had terrible earthquakes that killed thousands of people. Other decisions were made to give the \"American\" park a uniquely Japanese avor. The nation's penchant for buying edible souvenirs inspired a 6,000-square-foot confection shop packed with Japanese sweets such as dinosaur-shaped bean cakes. Restrooms include Japanese-style squat toilets. Even the park layout caters to the tendency of Japanese crowds to flow clockwise in an orderly manner, contrary to more chaotic U.S. 397 controlling The process of evaluating results in relation to plans or objectives and deciding what action, if any, to take. Part 3 International Strategic Management crowds that steer right. And millions of dollars were spent on the Jurassic Park water slide to widen the landing pond, redesign boat hulls, and install underwater wave-damping panels to reduce spray. Why? Many fastidious Japanese don't like to get wet, even on what's billed as one of the world's biggest water slides.33 The efforts to design a uniquely Japanese theme park with an American feel seem to be paying off. Fifteen years after first opening, Universal Studios Japan is now the fifth-mostvisited amusement park worldwide, attracting over [3 million visitors in 2015.34 Universal Studios Japan is the only non-Disney park to make the top-ten atten- dance list.35 The company has discovered that creating an emotional connection between the consumer and the park, instead of focusing on the power of Hollywood, encourages people to frequent the park. The success that Universal has had in integrating Japanese and American culture has encouraged the company to expand further into the Asian market; in fact, plans are already in place to open Universal Studios in Moscow, Beijing, and South Korea between 2020 and 2022.3'5'37 (See related discussion in In-Depth Integra- tive Case 2.1b on Disney in Asia at end of Part Two.) I The Controlling Process As we've stated, controlling involves evaluating results in relation to plans or objectives and deciding what action to take next. An excellent illustration of this process can be seen through ConocoPhillips' recent strategic changes to its investments in Russia. Over two decades ago, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U. S.-based company joined with Russian-based Rosneft to form the Polar Lights Company. The investment looked like a wise decision initially; teaming with Rosneft would allow ConocoPhillips access to Russia's massive oil and gas fields, and the deal made ConocoPhillips one of the largest foreign players inside of Russia. By the early 2000s, however, high taxes and unrealized returns worried executives and shareholders. After years of losses, ConocoPhillips sold its 50 percent stake in the joint venture in December 2015, freeing up capital for investments in more lucrative markets and projects.38 The control process is of course crucial for MNCs in the fast-moving personal computer (PC) business. Until the mid-I990s, PCs were built using the traditional model shown in Figure 1172. Today the direct-sales model and the hybrid model are the most common. PC firms are finding that they must keep on the cutting edge more than any other industry because of the relentless pace of technological change. This is where the control function becomes especially critical for success. For example, stringent controls keep the inventory in the system as small as possible. PCs are manufactured using a just-intime approach (a customer orders the unit and has it made to specifications) or an almost just-in-time approach (a retailer orders 30 units and sells them all within a few weeks). Because technology in the PC industry changes so quickly, any units that are not sold in retail outlets within 60 days may be outdated and must be severely discounted and sold for whatever the market will bear. In turn, these costs are often assumed by the manufacturer As a result, PC manufacturers are very much inclined to build to order or to ship in quantities that can be sold quickly. In this way the firm's control system helps ensure that inventory moves through the system profitably.39 Of particular interest is how companies attempt to control their overseas operations to become integrated, coordinated units. A number of control problems may arise: (l) The objectives of the overseas operation and the corporation conict. (2) The objec- tives of joint-venture partners and corporate management are not in accord. (3) Degrees of experience and competence in planning vary widely among managers running the various overseas units. (4) Finally, there may be basic philosophic disagreements about the objectives and policies of international operations, largely because of cultural differ- ences between home- and host-country managers. The following discussion examines the various types of control that are used in international operations and the approaches that are often employed in dealing with typical problems. Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control 399 Figure 1 12 Traditional Model Models of PC Manufacturing Based on sales The parts are The manufacturer The units are Orders are Customers buy forecasts, a wareh oused builds the PCs ordered by then received the PCs from manufacturer u ntil they are and stores them distributors from retailers the retailers orders pars for needed by the ->- in the warehouse. and shipped and the PCs and receive the PCs. manufacturer. to the latters' are shipped assistance in warehouses. to them by setting up the the distributors. entire system. Direct-Sales Model The manufacturer Business and The manufacturer The manufacturer orders a small individual builds the computer ships the computer number of parts customers place to the customers directly to the from its suppliers. orders by phone exact specifications. customer. or over the Internet. Hybrid Model The computer The shells are shipped The customer orders The distributor On the dealer's behalf, manufacturer to the distributors, and a computer through gathers the parts the distributor ships builds shells: a component suppliers a retailer or directly to assemble the the computer directly case, power establish a pars from the manufacturer, computer to the to the customer. The supply, USB inventory with, or near, and the order is customer's dealer then provides ports, basic that ofthe distributor. forwarded to the specifications. setup and additional circuitry. distributor. services for a separate fee. Types of Control There are two common, complementary ways of looking at how MNCs control opera- tions. One way is by determining whether the enterprise chooses to use internal or external control in devising its overall strategy. The other is by looking at the ways in which the organization uses direct and indirect controls. Internal and External Control From an internal control standpoint, an MNC will focus on the things that it does best. At the same time, of course, management wants to ensure that there is a market for the goods and services that it is offering. So the company first needs to find out what the customers want and be prepared to respond appropriately. This requires an external control focus. Naturally, every MNC will give consideration to both internal and external perspectives on control. However, one is often given more attention than the other. In explaining this idea, 'Il'ompenaars and Hampden-Tbrner set forth four management views regarding how a control strategy should be devised and implemented: 1. No one dealing with customers is without a strategy of sorts. Our task is to find out which of these strategies work, which don't, and why. Devising our own strategy in the abstract and imposing it downwards only spreads confusion. 2. No one dealing with customers is without a strategy of sorts. Our task is to find out which of these strategies work and then create a master strategy from proven successful initiatives by encouraging and combining the best. 400 Part 3 International Strategic Management 3. To be a leader is to be the chief deviser of strategy. Using all the experience, information, and intelligence we can mobilize, we need to devise an innova- tive strategy and then cascade it down the hierarchy. 4. To be a leader is to be the chief deviser of strategy. Using all the experience, information, and intelligence we can mobilize, we must create a broad thrust, while leaving it to subordinates to t these to customer needs. 'll'ompenaars and Hampden-Turner ask managers to rank each of these four state- ments by placing a \"1\" next to the one they feel would most likely be used in their company, a \"2\" next to the second most likely, on down to a \"4\" next to the one that would be the last choice. This ranking helps managers better see whether they use an external or an internal control approach. Answer 1 focuses most strongly on an external- directed approach and rejects the internal control option. Answer 3 represents the oppo- site. Answer 2 affirms a connection between an external-directed strategy and an inner-directed one, whereas answer 4 does the opposite.:10 Cultures differ in the control approach they use. For example, among US. MNCs it is common to find managers using an internal control approach. Among Asian firms an external control approach is more typical. Table 1 13 provides some contrasts between the two. direct controls Direct Controls Direct oontrols involve the use of face-to-face or personal meetings Theuse offaDE-IO-faoe 01' to monitor operations. A good example is how International Telephone and Telegraph personal mee'igs f_0r the (HT) holds monthly management meetings at its New York headquarters. These meet- IE'UIP'DSe 0f momtomg ings are run by the CEO of the company, and reports are submitted by each I'IT unit operations. manager throughout the world. Problems are discussed, goals set, evaluations made, and actions taken that will help the unit improve its effectiveness. Another common form of direct control is visits by top executives to overseas affiliates or subsidiaries. During these visits, top managers can learn firsthand the prob- lems and challenges facing the unit and offer assistance. A third form is the staffing practices of MNCs. By determining whom to send overseas to run the unit, the corporation can directly control how the operation will be run. The company will want the manager to make operating decisions and handle Table 113 The Impact of Internal- and External-Oriented Cultures on the Control Process Keyr Differences Between . . . Internal Control External Control Often dominating attitude bordering on aggressiveness Often flexible attitude, willing to compromise and keep the toward the environment. peace. Conflict and resistance mean that a person has convictions. Harmony, responsiveness, and sensibility are encouraged. The focus is on self, function, one's own group, and The focus is on others such as customers, partners, and one's own organization. colleagues. There is discomfort when the environment seems "out There is comfort with waves, shifts, and cycles, which are of control" or changeable. regarded as \"n atural." Tips for Doing Business with . . . Internally Controlled [for externals) Externally Controlled (for internals) Playing \"hardball" is legitimate to test the resilience Softness, persistence, politeness, and long patience will get of an opponent. rewards. It is most important to \"win your objective." It is most important to maintain one's relationships with others. Win some, lose some. Win together, lose apart. Source: Adapted from Fons Trompenaars and Charles HammettTuner, Rhli'rg the While-S of 01mm: Umermmhg Dfuersy in Global rsr'ness, 2nd ed. (New 'rtlrlc McGrawHill, 1993], pp. 150161. Chapter 11 Management Decision and Control day-to-day matters, but the individual also will know which decisions should be cleared with the home office. In fact, this approach to direct control sometimes results in a man- ager who is more responsive to central management than to the needs of the local unit. And nally, a fourth form is the organizational structure itself. By designing a structure that makes the unit highly responsive to home-office requests and communica- tions, the MNC ensures that all overseas operations are run in accord with central man- agement's desires. This structure can be established through formal reporting relationships and chain of command (who reports to whom). Indirect Controls Indirect controls involve the use of reports and other written forms of communication to control operations. One of the most common examples is the use of monthly operating reports that are sent to the home office. Other examples, which typically are used to supplement the operating report, include financial statements, such as balance sheets, income statements, cash budgets, and financial ratios that provide insights into the unit's financial health. The home office will use these operating and financial data to evaluate how well things are going and make decisions regarding necessary changes. Three sets of nancial statements usually are required from subsidiaries: (1) statements prepared to meet the national accounting standards and procedures prescribed by law and other professional organizations in the host country, (2) statements prepared to comply with the accounting principles and standards required by the home country, and (3) statements prepared to meet the financial consolidation requirements of the home country. Indirect controls are particularly important in international management because of the great expense associated with direct methods of control. Typically, MNCs will use indirect controls to monitor performance on a monthly basis, whereas direct controls are used semiannually or annually. This dual approach often provides the company with effective control of its operations at a price that also is cost-effective. Approaches to Control International managers can employ many different approaches to control. These approaches typically are dictated by the MNC's philosophy of control, the economic environment in which the overseas unit is operating, and the needs and desires of the managerial personnel who staff the unit. Working within control parameters, MNCs will structure their processes so that they are as efficient and effective as possible. Typically, the tools used will give the unit manager the autonomy needed to adapt to changes in the market as well as to attract competent local personnel. These tools will also provide for coordination of operations with the home office, so that the overseas unit operates in harmony with the MNC's overall strategic plan. Some control tools are universal. For example, all MNCs use financial tools in monitoring overseas units. This was true as long as four decades ago, when the following was reported: The crosscultural homogeneity in nancial control is in marked contrast to the heterogeneity exercised over the areas of international operations. American subsidiaries of Italian and Scandinavian rms are virtually independent operationally from their parents in functions pertaining to marketing, production, and research and development; whereas, the subsidiar ies of German and British rms have limited freedom in these areas. Almost no autonomy on financial matters is given by any nationality to the subsidiaries.\" Some Major Differences MNCs control operations in many different ways, and these often vary considerably from country to country. For example, how British firms moni- tor their overseas operations often is different from how German or French firms do. Similarly, U.S. MNCs tend to have their own approach to controlling, and it differs from both European and Japanese approaches. When Horovitz examined the key characteristics of top management control in Great Britain, Germany, and France, he found that British controls had four common characteristics: (1) Financial records were sophisticated and indirect controls The use of reports and other written forms of communication to control operations. Part 3 International Strategic Management heavily emphasized. (2) Top management tended to focus its attention on major problem areas and did not get involved in specific, detailed matters of control. (3) Control was used more for general guidance than for surveillance. (4) Operating units had a large amount of marketing autonomy.'12 This model was in marked contrast to that of German managers, who employed very detailed control and focused attention on all variances large and small. These man- agers also placed heavy control on the production area and stressed operational effi- ciency. In achieving this centralized control, managers used a large central staff for measuring performance, analyzing variances, and compiling quantitative reports for senior executives. Overall, the control process in the German firms was used as a polic- ing and surveillance instrument. French managers employed a control system that was closer to that of the Germans than to the British. Control was used more for surveillance than for guiding operations, and the process was centrally administered. Even so, the French system was less systematic and sophisticated.43 How do U.S. MNCs differ from their European counterparts? One comparative study found that a major difference is that U.S. firms tend to rely much more heavily on reports and other performance-related data. Americans make greater use of output control, and Europeans rely more heavily on behavioral control. Commenting on the differences between these two groups, the researcher noted: "This pattern appears to be quite robust and continues to exist even when a number of common factors that seem to influence control are taken into account.\"44 Some specific findings from this study include 1. Control in U.S. MNCs focuses more on the quantiable, objective aspects of a foreign subsidiary, whereas control in European MNCs tends to be used to measure more qualitative aspects. The U.S. approach allows comparative anal- yses between other foreign operations as well as domestic units; the European measures are more exible and allow control to be exercised on a unit-by- unit basis. 2. Control in U.S. MNCs requires more precise plans and budgets in generating suitable standards for comparison. Control in European MNCs requires a high level of companywide understanding and agreement regarding what consti- tutes appropriate behavior and how such behavior supports the goals of both the subsidiary and the parent firm. 3. Control in U.S. MNCs requires large central staffs and centralized information- processing capability. Control in European MNCs requires a larger cadre of capable expatriate managers who are willing to spend long periods of time abroad. This control characteristic is reflected in the career approaches used in the various MNCs. Although U.S. multinationals do not encourage lengthy stays in foreign management positions, European MNCs often regard these positions as stepping-stones to higher offices. 4. Control in European MNCs requires more decentralization of operating decision making than does control in U.S. MNCs. 5. Control in European MNCs favors short vertical spans or reporting channels from the foreign subsidiary to responsible positions in the parent'15 As noted in the discussion of decision making, these differences help explain why many researchers have found European subsidiaries to be more decentralized

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts