the word limit should be 800 to 1000 words so please give the answers as requirement. In summary, it's time to understand your parcel characteristics

the word limit should be 800 to 1000 words so please give the answers as requirement.

the word limit should be 800 to 1000 words so please give the answers as requirement.

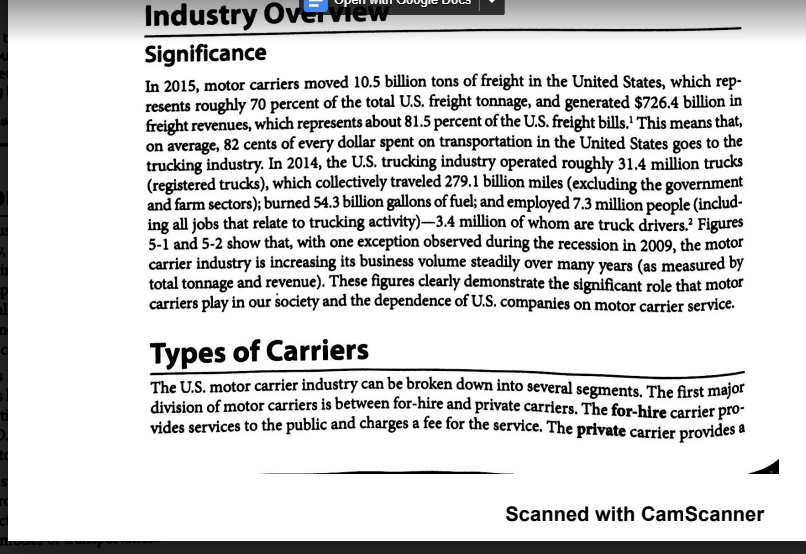

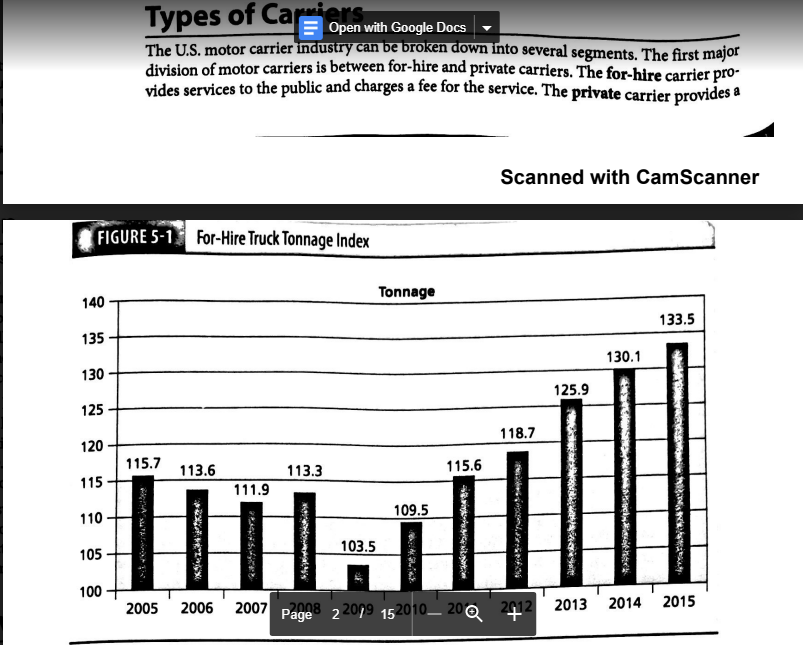

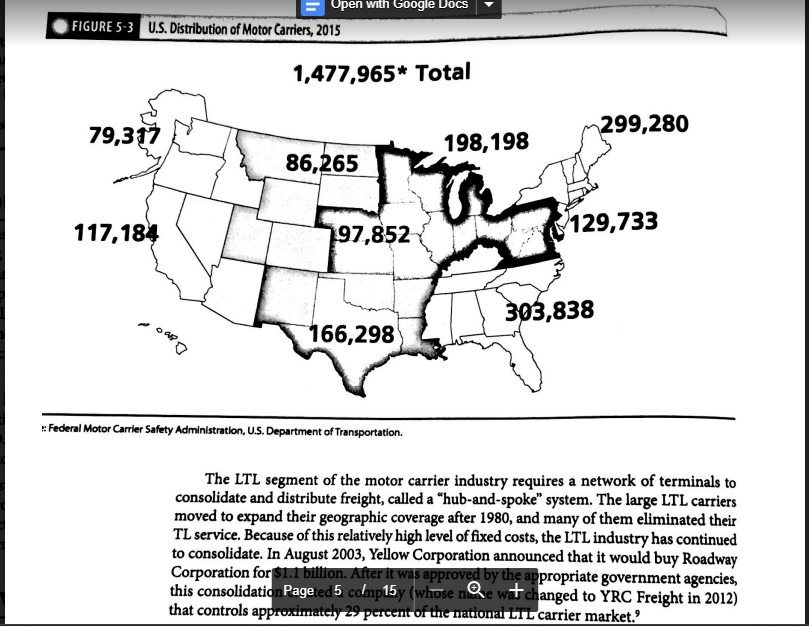

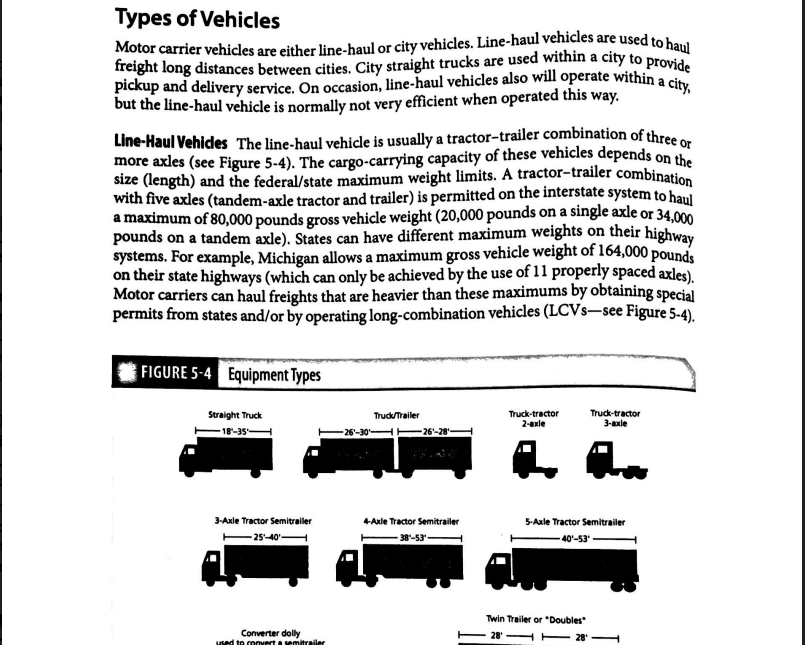

In summary, it's time to understand your parcel characteristics as well as how the car- riers will view your business. If you can position yourself and partners to be a shipper that parcel carriers can serve profitably, you will be rewarded with better discounts and have stronger negotiating leverage. Source: Peter Moore, Logistics Management, March 2017, p. 18. Reprinted with permission of Peerless Media, LLC. Introduction The motor carrier industry played an important role in the development of the U.S. economy during the 20th century, and it continues this role in the 21st century. The growth of this industry is noteworthy considering it did not get started until World War I, when converted automobiles were utilized for pickup and delivery in local areas. The railroad industry, which traditionally had difficulty with small shipments that had to be moved short distances, encouraged the early motor carrier entrepreneurs. It was not until after World War II that the railroad industry began to seriously attempt to compete with the motor carrier industry, and by that time it was too late. The United States has spent more than $128.9 billion to construct its interstate highway system and the process has become increasingly dependent on this system for the movement of freight. The major portion of this network evolved as the result of a bill signed into law in 1956 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to establish the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, which was to be funded 90 percent by the federal government through fuel taxes. As the interstate system of highways developed from the 1950s to 1991, motor carriers steadily replaced railroads as the mode of choice for transporting finished and unfinished manufactured products. Today, motor carriers have the largest share of U.S. freight move- ments among all the modes of transportation. Q + Page 1 15

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Motor Carrier Industry Visibility and Significance The motor carrier industry is the most prominent segment of the US transportation system due to its extensive reach and versatility Several factors a...

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started