Thoroughly analyse the given case. Also provide the necessary calculations with steps.

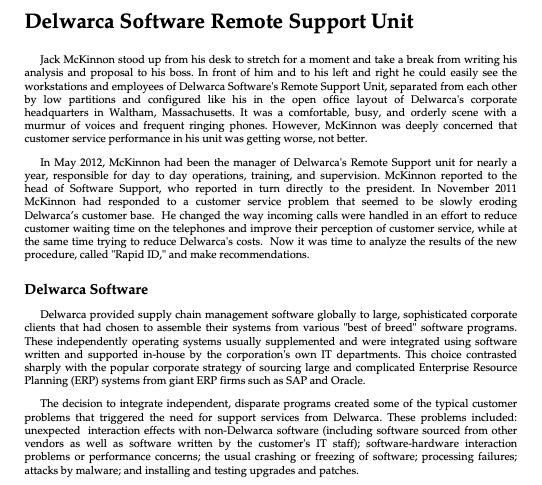

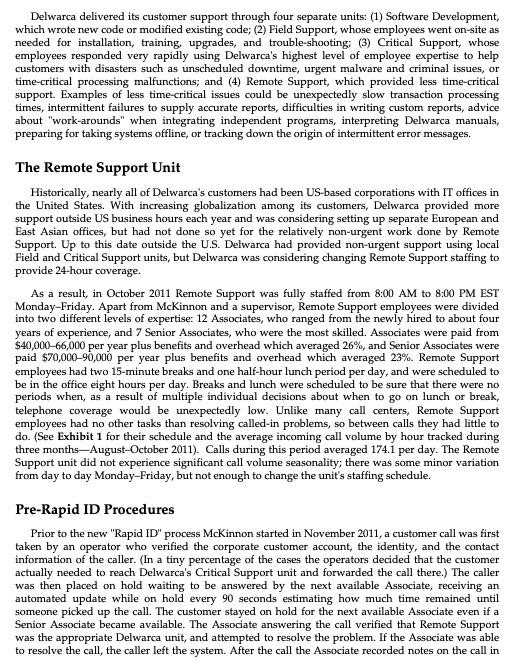

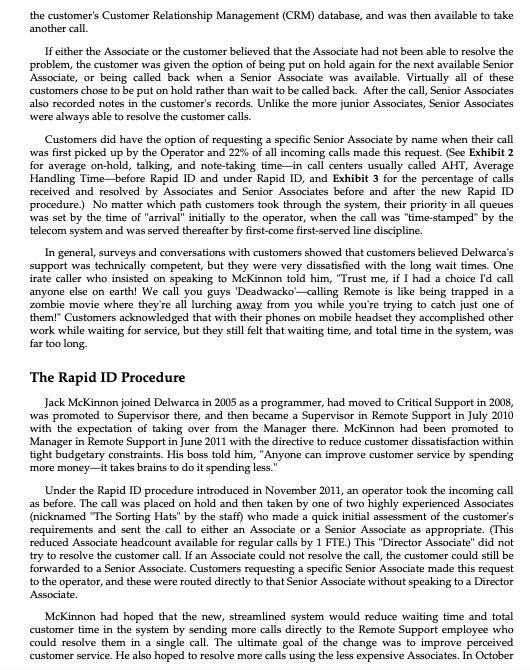

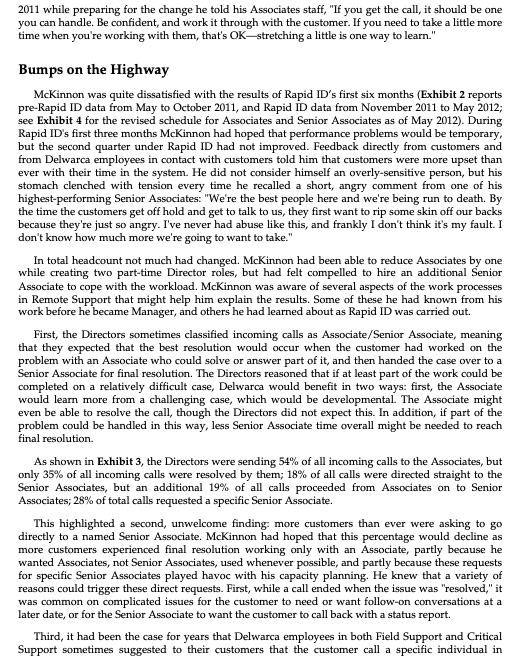

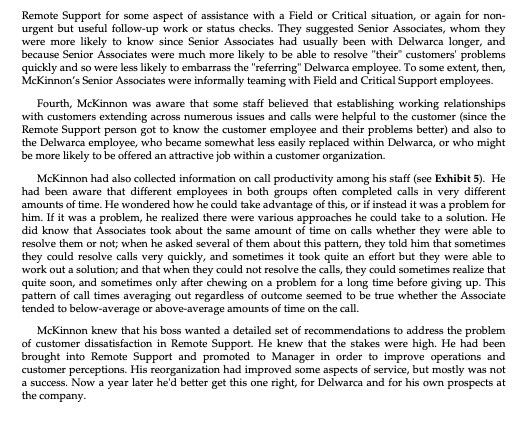

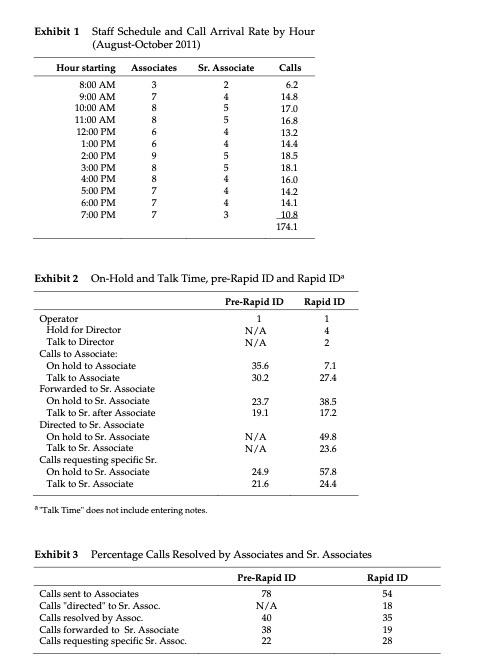

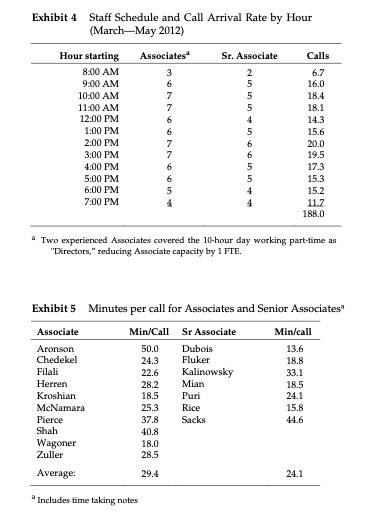

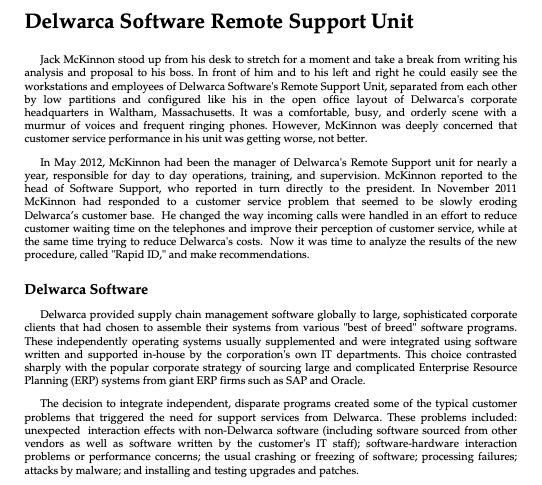

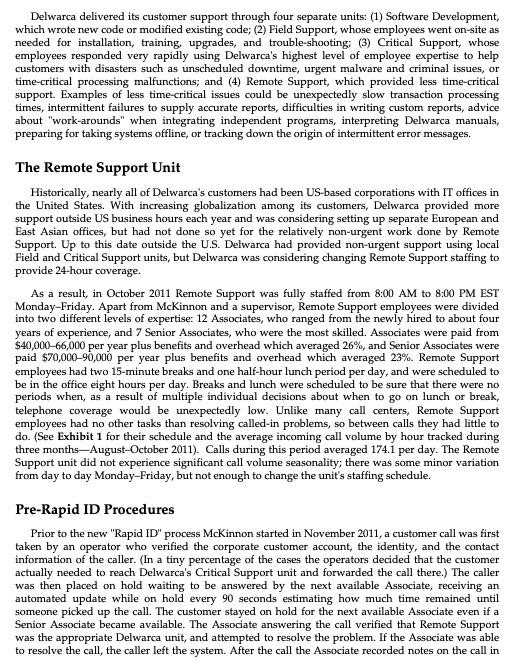

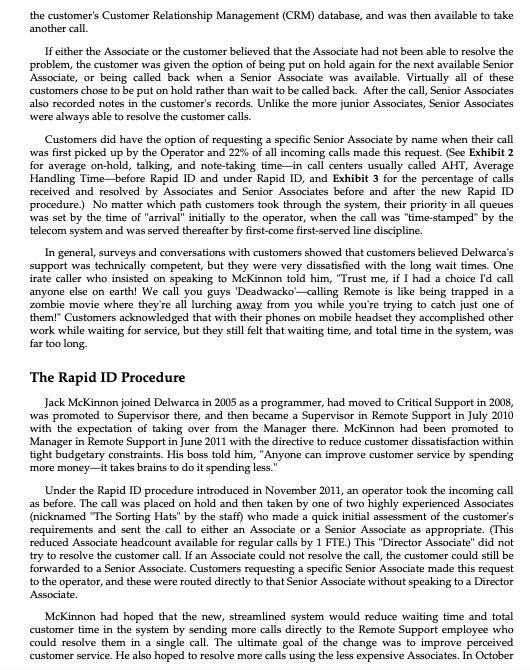

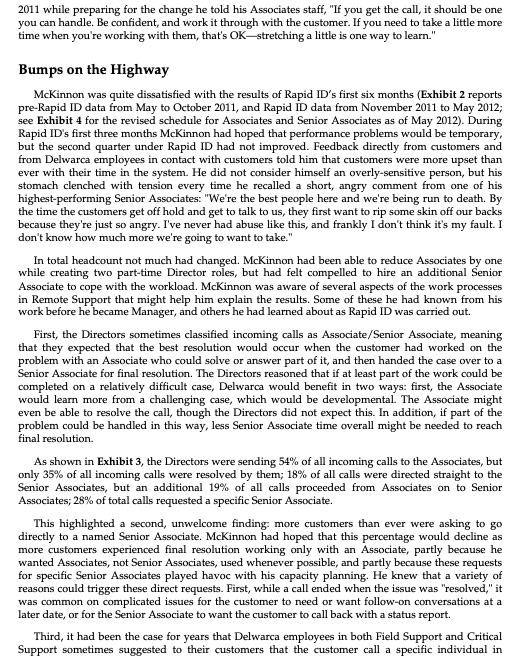

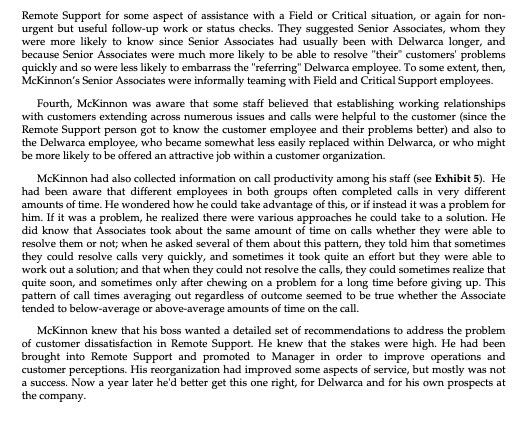

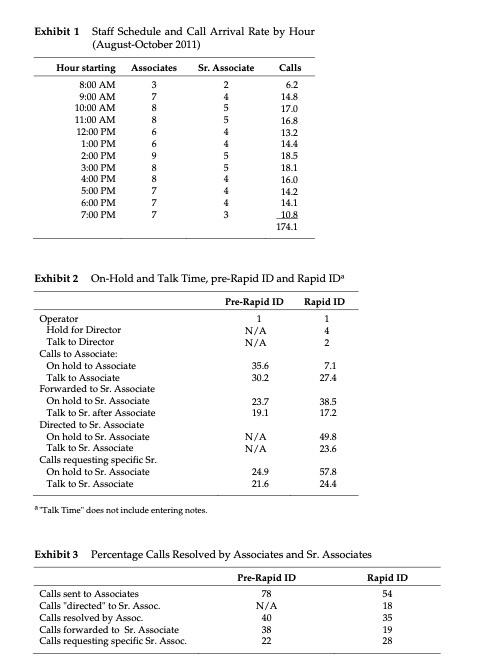

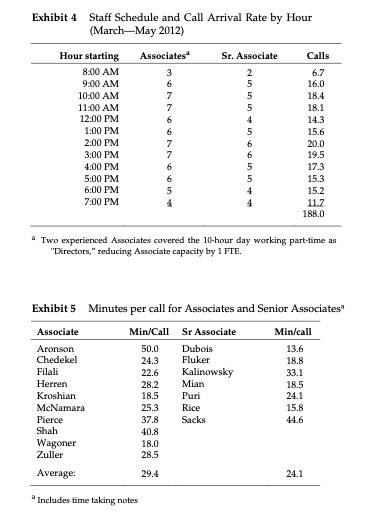

Exhibit 1 Staff Schedule and Call Arrival Rate by Hour (August-October 2011) Exhibit 2 On-Hold and Talk Time, pre-Rapid ID and Rapid ID "Talk Time" does not include entering notes. Exhibit 3 Percentage Calls Resolved by Associates and Sr. Associates Exhibit 4 Staff Schedule and Call Arrival Rate by Hour (March-May 2012) a Two experienced Associates covered the 10-hour day working part-time as "Directors," reducing Associate capacity by 1 FTE. Exhibit 5 Minutes per call for Associates and Senior Associates a "Includes time taking notes Remote Support for some aspect of assistance with a Field or Critical situation, or again for nonurgent but useful follow-up work or status checks. They suggested Senior Associates, whom they were more likely to know since Senior Associates had usually been with Delwarca longer, and because Senior Associates were much more likely to be able to resolve "their" customers' problems quickly and so were less likely to embarrass the "referring" Delwarca employee. To some extent, then, McKinnon's Senior Associates were informally teaming with Field and Critical Support employees. Fourth, McKinnon was aware that some staff believed that establishing working relationships with customers extending across numerous issues and calls were helpful to the customer (since the Remote Support person got to know the customer employee and their problems better) and also to the Delwarca employee, who became somewhat less easily replaced within Delwarca, or who might be more likely to be offered an attractive job within a customer organization. McKinnon had also collected information on call productivity among his staff (see Exhibit 5). He had been aware that different employees in both groups often completed calls in very different amounts of time. He wondered how he could take advantage of this, or if instead it was a problem for him. If it was a problem, he realized there were various approaches he could take to a solution. He did know that Associates took about the same amount of time on calls whether they were able to resolve them or not; when he asked several of them about this pattern, they told him that sometimes they could resolve calls very quickly, and sometimes it took quite an effort but they were able to work out a solution; and that when they could not resolve the calls, they could sometimes realize that quite soon, and sometimes only after chewing on a problem for a long time before giving up. This pattern of call times averaging out regardless of outcome seemed to be true whether the Associate tended to below-average or above-average amounts of time on the call. McKinnon knew that his boss wanted a detailed set of recommendations to address the problem of customer dissatisfaction in Remote Support. He knew that the stakes were high. He had been brought into Remote Support and promoted to Manager in order to improve operations and customer perceptions. His reorganization had improved some aspects of service, but mostly was not a success. Now a year later he'd better get this one right, for Delwarca and for his own prospects at the company. Delwarca Software Remote Support Unit Jack McKinnon stood up from his desk to stretch for a moment and take a break from writing his analysis and proposal to his boss. In front of him and to his left and right he could easily see the workstations and employees of Delwarca Software's Remote Support Unit, separated from each other by low partitions and configured like his in the open office layout of Delwarca's corporate headquarters in Waltham, Massachusetts. It was a comfortable, busy, and orderly scene with a murmur of voices and frequent ringing phones. However, McKinnon was deeply concerned that customer service performance in his unit was getting worse, not better. In May 2012, McKinnon had been the manager of Delwarca's Remote Support unit for nearly a year, responsible for day to day operations, training, and supervision. McKinnon reported to the head of Software Support, who reported in turn directly to the president. In November 2011 McKinnon had responded to a customer service problem that seemed to be slowly eroding Delwarca's customer base. He changed the way incoming calls were handled in an effort to reduce customer waiting time on the telephones and improve their perception of customer service, while at the same time trying to reduce Delwarca's costs. Now it was time to analyze the results of the new procedure, called "Rapid ID," and make recommendations. Delwarca Software Delwarca provided supply chain management software globally to large, sophisticated corporate clients that had chosen to assemble their systems from various "best of breed" software programs. These independently operating systems usually supplemented and were integrated using software written and supported in-house by the corporation's own IT departments. This choice contrasted sharply with the popular corporate strategy of sourcing large and complicated Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems from giant ERP firms such as SAP and Oracle. The decision to integrate independent, disparate programs created some of the typical customer problems that triggered the need for support services from Delwarca. These problems included: unexpected interaction effects with non-Delwarca software (including software sourced from other vendors as well as software written by the customer's IT staff); software-hardware interaction problems or performance concerns; the usual crashing or freezing of software; processing failures; attacks by malware; and installing and testing upgrades and patches. Delwarca delivered its customer support through four separate units: (1) Software Development, which wrote new code or modified existing code; (2) Field Support, whose employees went on-site as needed for installation, training, upgrades, and trouble-shooting; (3) Critical Support, whose employees responded very rapidly using Delwarca's highest level of employee expertise to help customers with disasters such as unscheduled downtime, urgent malware and criminal issues, or time-critical processing malfunctions; and (4) Remote Support, which provided less time-critical support. Examples of less time-critical issues could be unexpectedly slow transaction processing times, intermittent failures to supply accurate reports, difficulties in writing custom reports, advice about "work-arounds" when integrating independent programs, interpreting Delwarca manuals, preparing for taking systems offline, or tracking down the origin of intermittent error messages. The Remote Support Unit Historically, nearly all of Delwarca's customers had been US-based corporations with IT offices in the United States. With increasing globalization among its customers, Delwarca provided more support outside US business hours each year and was considering setting up separate European and East Asian offices, but had not done so yet for the relatively non-urgent work done by Remote Support. Up to this date outside the U.S. Delwarca had provided non-urgent support using local Field and Critical Support units, but Delwarca was considering changing Remote Support staffing to provide 24-hour coverage. As a result, in October 2011 Remote Support was fully staffed from 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM EST Monday-Friday. Apart from McKinnon and a supervisor, Remote Support employees were divided into two different levels of expertise: 12 Associates, who ranged from the newly hired to about four years of experience, and 7 Senior Associates, who were the most skilled. Associates were paid from $40,00066,000 per year plus benefits and overhead which averaged 26%, and Senior Associates were paid $70,00090,000 per year plus benefits and overhead which averaged 23%. Remote Support employees had two 15-minute breaks and one half-hour lunch period per day, and were scheduled to be in the office eight hours per day. Breaks and lunch were scheduled to be sure that there were no periods when, as a result of multiple individual decisions about when to go on lunch or break, telephone coverage would be unexpectedly low. Unlike many call centers, Remote Support employees had no other tasks than resolving called-in problems, so between calls they had little to do. (See Exhibit 1 for their schedule and the average incoming call volume by hour tracked during three months-August-October 2011). Calls during this period averaged 174.1 per day. The Remote Support unit did not experience significant call volume seasonality; there was some minor variation from day to day Monday-Friday, but not enough to change the unit's staffing schedule. Pre-Rapid ID Procedures Prior to the new "Rapid ID" process McKinnon started in November 2011, a customer call was first taken by an operator who verified the corporate customer account, the identity, and the contact information of the caller. (In a tiny percentage of the cases the operators decided that the customer actually needed to reach Delwarca's Critical Support unit and forwarded the call there.) The caller was then placed on hold waiting to be answered by the next available Associate, receiving an automated update while on hold every 90 seconds estimating how much time remained until someone picked up the call. The customer stayed on hold for the next available Associate even if a Senior Associate became available. The Associate answering the call verified that Remote Support was the appropriate Delwarca unit, and attempted to resolve the problem. If the Associate was able to resolve the call, the caller left the system. After the call the Associate recorded notes on the call in 2011 while preparing for the change he told his Associates staff, "If you get the call, it should be one you can handle. Be confident, and work it through with the customer. If you need to take a little more time when you're working with them, that's OK-stretching a little is one way to learn." Bumps on the Highway McKinnon was quite dissatisfied with the results of Rapid ID's first six months (Exhibit 2 reports pre-Rapid ID data from May to October 2011, and Rapid ID data from November 2011 to May 2012; see Exhibit 4 for the revised schedule for Associates and Senior Associates as of May 2012). During Rapid ID's first three months McKinnon had hoped that performance problems would be temporary, but the second quarter under Rapid ID had not improved. Feedback directly from customers and from Delwarca employees in contact with customers told him that customers were more upset than ever with their time in the system. He did not consider himself an overly-sensitive person, but his stomach clenched with tension every time he recalled a short, angry comment from one of his highest-performing Senior Associates: "We're the best people here and we're being run to death. By the time the customers get off hold and get to talk to us, they first want to rip some skin off our backs because they're just so angry. I've never had abuse like this, and frankly I don't think it's my fault. I don't know how much more we're going to want to take." In total headcount not much had changed. McKinnon had been able to reduce Associates by one while creating two part-time Director roles, but had felt compelled to hire an additional Senior Associate to cope with the workload. McKinnon was aware of several aspects of the work processes in Remote Support that might help him explain the results. Some of these he had known from his work before he became Manager, and others he had learned about as Rapid ID was carried out. First, the Directors sometimes classified incoming calls as Associate/Senior Associate, meaning that they expected that the best resolution would occur when the customer had worked on the problem with an Associate who could solve or answer part of it, and then handed the case over to a Senior Associate for final resolution. The Directors reasoned that if at least part of the work could be completed on a relatively difficult case, Delwarca would benefit in two ways: first, the Associate would learn more from a challenging case, which would be developmental. The Associate might even be able to resolve the call, though the Directors did not expect this. In addition, if part of the problem could be handled in this way, less Senior Associate time overall might be needed to reach final resolution. As shown in Exhibit 3, the Directors were sending 54\% of all incoming calls to the Associates, but only 35% of all incoming calls were resolved by them; 18% of all calls were directed straight to the Senior Associates, but an additional 19% of all calls proceeded from Associates on to Senior Associates; 28% of total calls requested a specific Senior Associate. This highlighted a second, unwelcome finding: more customers than ever were asking to go directly to a named Senior Associate. McKinnon had hoped that this percentage would decline as more customers experienced final resolution working only with an Associate, partly because he wanted Associates, not Senior Associates, used whenever possible, and partly because these requests for specific Senior Associates played havoc with his capacity planning. He knew that a variety of reasons could trigger these direct requests. First, while a call ended when the issue was "resolved," it was common on complicated issues for the customer to need or want follow-on conversations at a later date, or for the Senior Associate to want the customer to call back with a status report. Third, it had been the case for years that Delwarca employees in both Field Support and Critical Support sometimes suggested to their customers that the customer call a specific individual in the customer's Customer Relationship Management (CRM) database, and was then available to take another call. If either the Associate or the customer believed that the Associate had not been able to resolve the problem, the customer was given the option of being put on hold again for the next available Senior Associate, or being called back when a Senior Associate was available. Virtually all of these customers chose to be put on hold rather than wait to be called back. After the call, Senior Associates also recorded notes in the customer's records. Unlike the more junior Associates, Senior Associates were always able to resolve the customer calls. Customers did have the option of requesting a specific Senior Associate by name when their call was first picked up by the Operator and 22% of all incoming calls made this request. (See Exhibit 2 for average on-hold, talking, and note-taking time-in call centers usually called AHT, Average Handling Time-before Rapid ID and under Rapid ID, and Exhibit 3 for the percentage of calls received and resolved by Associates and Senior Associates before and after the new Rapid ID procedure.) No matter which path customers took through the system, their priority in all queues was set by the time of "arrival" initially to the operator, when the call was "time-stamped" by the telecom system and was served thereafter by first-come first-served line discipline. In general, surveys and conversations with customers showed that customers believed Delwarca's support was technically competent, but they were very dissatisfied with the long wait times. One irate caller who insisted on speaking to McKinnon told him, "Trust me, if I had a choice I'd call anyone else on earth! We call you guys 'Deadwacko'-calling Remote is like being trapped in a zombie movie where they're all lurching away from you while you're trying to catch just one of them!" Customers acknowledged that with their phones on mobile headset they accomplished other work while waiting for service, but they still felt that waiting time, and total time in the system, was far too long. The Rapid ID Procedure Jack McKinnon joined Delwarca in 2005 as a programmer, had moved to Critical Support in 2008, was promoted to Supervisor there, and then became a Supervisor in Remote Support in July 2010 with the expectation of taking over from the Manager there. McKinnon had been promoted to Manager in Remote Support in June 2011 with the directive to reduce customer dissatisfaction within tight budgetary constraints. His boss told him, "Anyone can improve customer service by spending more money -it takes brains to do it spending less." Under the Rapid ID procedure introduced in November 2011, an operator took the incoming call as before. The call was placed on hold and then taken by one of two highly experienced Associates (nicknamed "The Sorting Hats" by the staff) who made a quick initial assessment of the customer's requirements and sent the call to either an Associate or a Senior Associate as appropriate. (This reduced Associate headcount available for regular calls by 1 FTE.) This "Director Associate" did not try to resolve the customer call. If an Associate could not resolve the call, the customer could still be forwarded to a Senior Associate. Customers requesting a specific Senior Associate made this request to the operator, and these were routed directly to that Senior Associate without speaking to a Director Associate. McKinnon had hoped that the new, streamlined system would reduce waiting time and total customer time in the system by sending more calls directly to the Remote Support employee who could resolve them in a single call. The ultimate goal of the change was to improve perceived customer service. He also hoped to resolve more calls using the less expensive Associates. In October