Question

TiVo Case Study TiVo KEL132 Revised September 14, 2011 As Brody Keast, TiVo's senior vice president of marketing, pored over research reports and market forecasts,

TiVo Case Study

TiVo

KEL132

Revised September 14, 2011

As Brody Keast, TiVo's senior vice president of marketing, pored over research reports and market forecasts, his excitement grew. In one report Odyssey Research concluded, "We have never seen a product test better in terms of consumer intent to purchase." A report from AC Nielsen Vantis was equally enthusiastic, noting, "Of forty-four consumer electronics concepts we have tested, we've never had a product test as high in what we call the trifecta: intensity of liking, new and different, and need fulfillment." TiVo's market prospects seemed even brighter than Keast had dared to hope.

At the same time, Keast recognized that the TiVo launch would need to be managed carefully. The company's goal was extremely ambitious: it hoped to revolutionize how Americans watch television and become a central player in the emerging interactive TV industry. Competitors such as ReplayTV had similar products and designs on the future, so TiVo's success was far from guaranteed. Keast believed that the product positioning at launch would play a key role in determining who would win the race to personalize television viewing.

The Vision

Americans have a love/hate relationship with television. In all, 98 percent of the country's 100 million households own at least one TV. On average, each household has 2.4 TVs and spends seven hours and fifteen minutes per day viewing television. In 1999, 78.1 million households spent $34.4 billion to receive cable TV service, while another 14.5 million households received subscription-based satellite TV service. These services gave consumers access to a growing number of channels, as the typical cable customer can receive more than 53 channels.

While Americans spend a great deal of time in front of the TV, they are far from satisfied with the experience. Common complaints are that favorite programs are not on when they have time to watch TV, viewing is often interrupted by phone calls and family demands, and the VCR, which might be used to address these problems, is difficult to program. In a TV lover's ideal world, his favorite shows would always be available, programming would be developed to his personal taste, shows would start when he wanted them to, and live TV could be paused, slowed, or rewound.

Jim Barton and Mike Ramsay founded TiVo in San Jose, California, in August 1997 with the goal of increasing consumers' control over their television viewing. They envisioned a set-top box, referred to as a personal video recorder (PVR) or a digital video recorder (DVR), combined with a subscription service. The system, which they named TiVo, would allow the user to search a complete guide of television programs and digitally store between 20 and 60 hours of desired programming. It would also let users view special programming, receive personalized viewing suggestions, and control live television through the use of pause, slow motion, rewind, and fast- forward buttons.

Barton and Ramsay recognized that they lacked the resources to manufacture and build a PVR/DVR brand. Instead they partnered with two well-respected consumer electronics companies, Sony and Philips, who agreed to manufacture PVRs/DVRs carrying both the manufacturer's brand name and the TiVo name. TiVo would subsidize the production of the PVRs/DVRs so the price for lower-end models could be under $500, with the hope that this would speed market penetration.

TiVo planned to charge a modest monthly fee ($9.95) for the subscription service. Alternatively, subscribers could purchase a lifetime product membership for $199. Initially the subscription fee would be the company's primary source of revenue, but once a critical mass of consumers adopted TiVo, the detailed data regarding viewers' behavior and preferences captured by the subscription service was anticipated to be a major revenue source. This data could be used to create value-driven interactive television (iTV) and sell targeted access to advertisers and programmers.

Barton and Ramsay's business model was very appealing to investors. They quickly attracted significant financial backing from prominent venture capitalists and AOL/Time Warner invested more than $240 million.

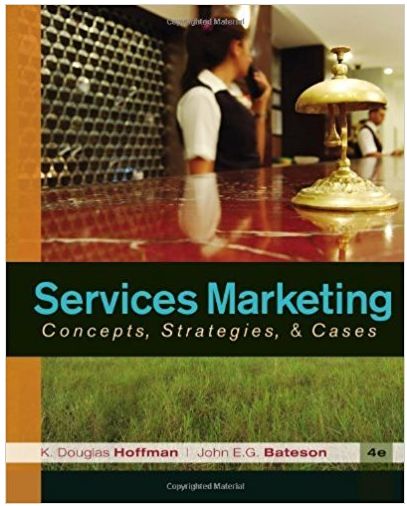

The TiVo System

By design, TiVo resembles a computer with a high-performance Power PC running a Linux operating system. TiVo's most-important feature is its hard drive, which stores the recorded TV programs in a digital format. For cost and compatibility considerations, TiVo uses the same hard drives that are used in desktop computers. TiVo works as follows: When a program is recorded, the incoming information is converted to a digital format and then compressed into MPEG II format, similar to the format used to create DVDs (see Exhibit 1). The compressed recordings are stored on the hard drive as separate files, allowing random, or nonlinear, access to individual programs. The hard drive can record and compress recordings around the clock and all the programming, including live TV, is digitally processed before being displayed on the TV screen. Because the analog signal is converted to digital format, compressed, decompressed, and then converted back to analog, image quality is sometimes affected. The loss of quality is visible when TiVo is hooked up to a high definition or HD-ready TV.

Recording capacity can be set for 20, 30, or 60 hours, depending on configuration. Consumers can further control the recording quality by varying the degree of compression; PVRs/DVRs can set to record at basic, better, or best quality. When set at "best," a level considered appropriate for recording sports events, the storage capacity is roughly one-third of that at the basic, advertised level.

Using an existing telephone line, the TiVo recorder downloads up-to-date programming information and unique TiVo content every day (usually very early in the morning). Upgrades and enhancements to the TiVo service are also automatically delivered via the phone line, but TiVo is specifically designed not to interrupt incoming or outgoing calls.

Low-end TiVo models that store 20 hours of basic-quality programming are priced at $299, while higher-end models that store up to 60 hours of basic programming are priced at $699 (MSRP).

The computer-like design of TiVo offers customers numerous functional benefits, including:

? The ability to pause, slow motion (including frame by frame), and instantly replay live TV

? A fast-forward option that lets users choose which program to watch or skip

? Simultaneous playback and record

? The ability to skip commercials

? Direct (nonlinear) access to all pre-recorded programs

? Advanced search and recording that lets viewers (or even TiVo itself) find and record programs based on a favorite actor, director, genre, or show

? A program menu that includes program ratings, suggestions, tips, and more

? A season pass that will instruct the PVR/DVR to automatically record a favorite program

every time it airs for an entire season, regardless of time slot

? Thumbs-up and thumbs-down controls that allow the viewer to rate programs

? An intelligent agent (similar to that used by Amazon.com to make book and music recommendations) that stores viewer preferences, matches them with incoming program data, and recommends programs the viewer is likely to enjoy

? The ability to transfer favorite programming to a VCR using TiVo's remote control

? Parental controls to lock channels or set ratings limits on programs

Market Research

To gauge consumers' response to TiVo, Keast and his team commissioned several research projects. The first study was a series of focus groups conducted by Odyssey Research, a firm recommended by TiVo's venture capital partners. In these sessions, consumers were given a ten- minute demonstration of a TiVo prototype. They were told that the set-top box would cost $499 and the subscription service would be available at $9.95/month, or $199 for a lifetime membership.

While the focus group participants were very enthusiastic about the TiVo concept, they also expressed concerns. Several people worried that setting up the system seemed complicated and time consuming. Others loved the idea of TiVo, but felt that the price was too high and indicated that they would wait for prices to fall before purchasing. Several people were also initially confused about whether the PVR/DVR would replace their VCR or DVD player. Ultimately it took the moderator another ten minutes to clarify the role of the PVR/DVR.

The focus groups also provided insight into how consumers would likely shop for TiVo. Married participants indicated that the husband would be most likely to initiate consideration of TiVo and would collect the needed information, but the high price of the system meant the purchase would not be made unless the wife agreed to the expenditure. Participants also suggested that personal sources of information, such as friends and family, would influence their decision to buy TiVo. These findings converged with the results of a similar study examining the buying process for projection TV. That study revealed that the majority of projection TV buyers spent between one month and one year considering their purchase. They shopped at three or more stores and relied heavily upon sales people, magazine articles, and word-of-mouth from family, friends, and co-workers when making their selection.

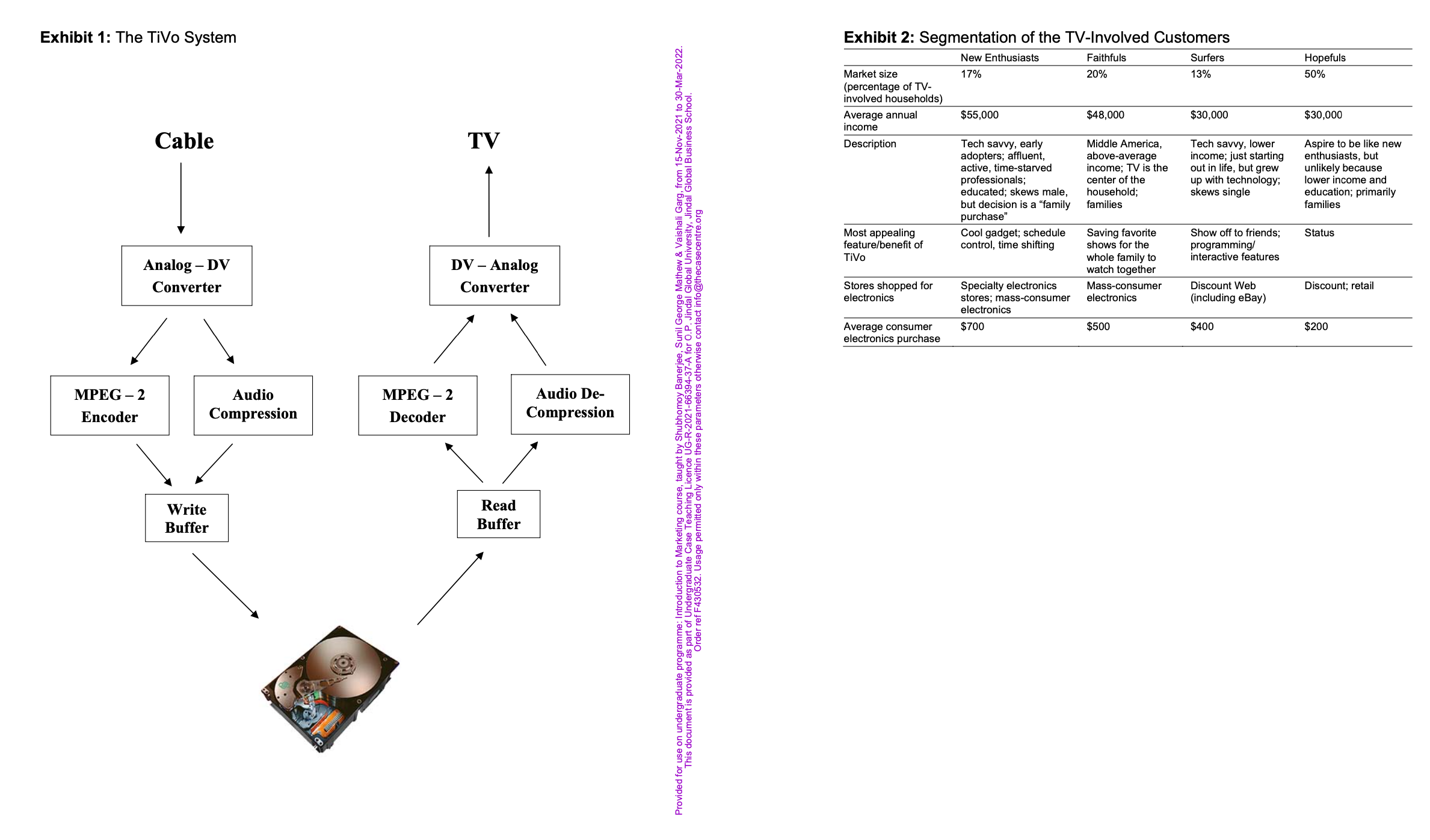

Finally, the focus groups indicated that, not surprisingly, TiVo's greatest appeal was to consumers who were TV involved. Further, the research firm identified four sub-segments of TV- involved consumers: new enthusiasts, faithfuls, surfers, and hopefuls (see Exhibit 2).

Mindful of these insights, Keast focused the next phase of research on households with at least one member who had higher-than-average TV involvement, as determined by the hours viewed per week. A sample of 2,000 consumers was recruited to participate in a concept test. The participants were shown a board with a picture of the TiVo system and a description of its features and benefits. On the basis of this information, 25 percent indicated that they would definitely or probably buy TiVo.

A few weeks later, these same individuals were given the opportunity to experience TiVo in their homes. After the trial, intent-to-purchase scores rose dramatically. In fact, 56 percent of participants indicated that they would definitely buy TiVo. An additional 34 percent said that they would probably buy. These scores compared quite favorably to the same consumers' response to DVD, where the numbers were 17 percent and 43 percent, respectively. Further, when given a competing set of consumer electronics products with market prices and a fixed number of dollars to hypothetically spend, they distributed the largest percent of their dollars (29 percent) to personal TV (PC received 18 percent, Digital TV 15 percent, DVD 10 percent, New TV 9 percent, VCR 5 percent, and WebTV 4 percent).

Finally, the participating households were offered favorable terms if they wished to purchase TiVo. The terms of the deal required that participants complete a survey after they had used the system for two months. Approximately half of the households took advantage of this offer. These households tended to be very involved with consumer electronics products in general, especially TV. Of the households participating in this phase of the research, 62 percent owned a DVD player, 46 percent had satellite service, and 70 percent had a surround sound system for their TV.

Results of the post-purchase survey provided several additional insights. When asked to describe how TiVo affected their viewing patterns, respondents reported that the Season Pass ensured they no longer missed their favorite programs, and the pause and rewind feature allowed them to view entire shows, even when they were interrupted. Pausing live TV had the greatest "wow" factor, though use of this feature waned significantly over the course of the trial period, largely because people watched less live TV over time. Overall, 66 percent of respondents stated that they found TV with TiVo to be a more satisfying form of entertainment than old-fashioned TV. Respondents also indicated that they would be a favorable word-of-mouth source for TiVo. In fact, 56 percent indicated that they would recommend TiVo to most or almost all of the people that they knew. Finally, in contrast to the concerns raised in the first focus groups, 68 percent of respondents reported that they found it easy to set up TiVo.

Overall, Keast was very encouraged by these findings. The data seemed to solidly support the marketing research firms' enthusiastic conclusions regarding consumer acceptance. TiVo's IHUT (in-home use test) results were especially encouraging once standard CPG (consumer packaged goods) purchase-intent-to-trial conversion rates were applied. Typically, 80 percent of those stating they will "definitely buy," and 20 percent of those stating they will "probably buy" actually do so. Given the very high proportion of people who indicated that they would either definitely or probably buy, the estimated sales volume was very promising.

Market Forecast and Competition

Keast was not the only one who believed that personal TV would be the wave of the future. In early 2000, Forrester, a leading technology market research firm, asserted, "These hard-drive machines will take off faster than any other consumer electronics product has before . . ." Forrester projected household penetration greater than 50 percent by 2005. A slightly more conservative forecast was made by Jupiter Communications, which predicted that PVRs/DVRs would penetrate 27 percent of households by 2004. In general, the consensus was that PVRs/DVRs would be adopted more rapidly than color television or VCR and would outpace forecasts for HDTV adoption (see Exhibit 3 and Exhibit 4). These predictions assumed a significantly higher rate of adoption than for handheld computers, which despite rapid growth between 1995 and 2000, were not expected to penetrate 50 percent of households in the foreseeable future. The analysts argued that PVR/DVR adoption would outpace the rest because none of the other products offered the level of consumer benefit or the universal appeal associated with personal TV.

In light of the bright predictions for PVRs/DVRs, it was not surprising that TiVo already had one competitor. ReplayTV was scheduled to launch a set-top box very similar to TiVo's base prototype model in the next few months. The ReplayTV PVRs/DVRs would cost about $100 more than a comparable TiVo PVR/DVR, but ReplayTV did not plan to charge for its service. Panasonic had agreed to produce ReplayTV's PVRs/DVRs, but TiVo management comforted themselves with the knowledge that they had significantly greater financial backing than ReplayTV .

At the same time, TiVo management knew that other companies were poised to enter if the market for PVRs/DVRs materialized as forecast. Among the likely entrants was Microsoft's Ultimate TV. With its relationship with WebTV, this was thought to be the greatest threat. TiVo's management hoped to be aggressive and capitalize on their first-mover advantage, but this meant that they would have to bear the brunt of educating consumers and driving adoption.

The Challenge

While Keast felt confident that consumers would ultimately embrace personal TV, he was less certain about the best approach for launching TiVo. He knew the company needed strong initial sales for the IPO, which they hoped would occur within 18 to 24 months, to be a success. It was also important to capture the first-mover advantage and build a strong brand before formidable players such as Microsoft turned their attention to the market. At the same time he recognized that TiVo's greatest appeal was to TV-involved consumers who represented only 70 percent of the households, and that this broad category had several distinct sub-segments. As Keast stared at the piles of market research data, he knew it was time to take a stand. He was scheduled to present his recommendations for targeting and positioning to Jim Barton and Mike Ramsay the next morning.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started