TRUE OR FALSE AND WHY

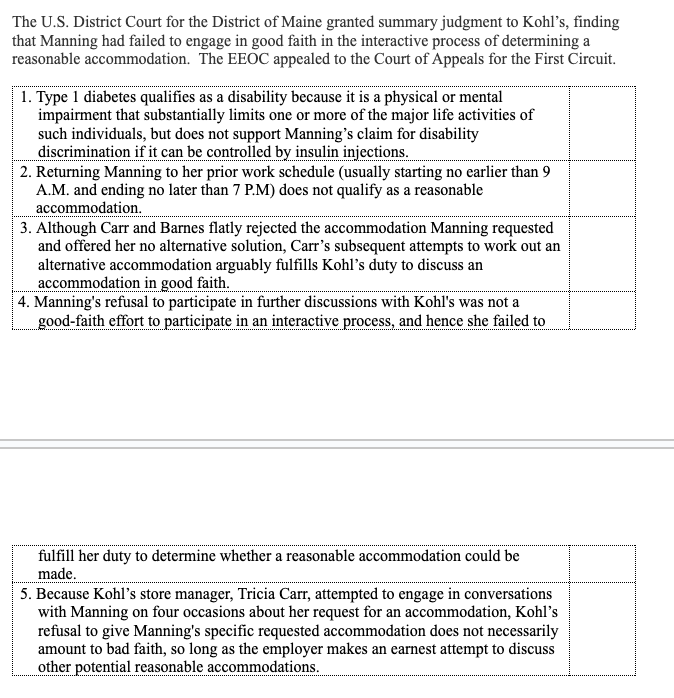

Case 2: EEOC v. Kohl's Dep't Stores, Inc., 774 F.3d 127 (1st Cir. 2014) (Prenkert, 18 th Ed., p. 51-31) Pamela Manning suffered from type I diabetes, a chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin, a hormone needed to allow glucose from the food one consumes to be processed at the cellular level to produce energy. Type I diabetics must carefully monitor their food intake, modulate their physical activity, regularly test their blood sugar levels, and often either take several insulin injections per day or use an insulin pump. Failure to properly treat type I diabetes can result in numerous and severe complications, including a potentially life-threatening condition known as diabetic ketoacidosis. Manning worked at Kohl's Department Stores in Maine as a sales associate for more than three years. In January 2010, Kohl's restructured the staffing of Manning's department such that she no longer had the opportunity to fulfill her full-time work hours solely within that department. As a result, she had to supplement her hours by working in various other departments depending on the store's needs. Prior to 2010, she had worked regular, predictable shifts that usually started no earlier than 9 A.M. and ended no later than 7 P.M. With the staffing shuffle, Manning began working unpredictable shifts, including some "swing shifts" (i.e., a night shift one day followed by an early shift the next day). In March 2010, Manning informed her immediate supervisor, Michelle Barnes, that working the erratic shifts was aggravating her diabetes and endangering her health. She asked to be scheduled for more predictable hours. Barnes instructed Manning to obtain a doctor's note to support her request, which Manning did. Her endocrinologist, Dr. Irwin Brodsky, wrote a letter to the store manager, Tricia Carr, requesting that Manning be allowed to work "a predictable day shift" so that Manning could better manage her stress, glucose level, and insulin therapy. Carr contacted Kohl's human resources department for guidance in how to respond to Manning's request and Dr. Brosky's letter. Michael Treichler in Human Resources told Carr that Manning would still be required to work nights and weekends, but that Kohl's could ensure that she would have no swing shifts and that she always was able to take her breaks when she worked. Carr and Barnes met with Manning on March 31, 2010, to discuss the situation. Manning requested "a steady schedule" and "a midday shift" like she had before the departmental restructuring. Manning expressed a willingness to work on weekends. Carr responded that Kohl's corporate management had not authorized her to provide a consistently steady nine-to-five schedule. Hearing that, Manning became upset, told Carr she had no choice but to quit due to the risk her erratic schedule caused her of going into ketoacidosis or a coma, put her store keys on the table, walked out of Carr's office, and slammed the door. Carr followed Manning into the break room and asked her what she could do to help. Manning responded, "Well, you just told me Corporate wouldn't do anything for me." At that point, Carr and Manning did not discuss any other possible scheduling arrangements. Instead, Manning cleaned out her locker and left the building. A week or so later, Carr called Manning to request that she rethink her resignation and consider alternative accommodations. Manning asked about her schedule, and Carr responded that she would have to consult with the corporate office about it. Manning and Carr had no further contact after the phone call. In none of the conversations did Carr ever mention to Manning Treichler's assurance that Manning could be scheduled to avoid swing shifts. Manning filed a charge of discrimination with the EEOC, claiming among other things disability discrimination and failure to accommodate under the ADA. After investigation, the EEOC sued Kohl's on Manning's behalf. The U.S. District Court for the District of Maine granted summary judgment to Kohl's, finding that Manning had failed to engage in good faith in the interactive process of determining a reasonable accommodation. The EEOC appealed to the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit