Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Virginia Mason Medical Center (Abridged) Physician Dr. Gary Kaplan became CEO of Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) in Seattle, Washington, in 2000. It was

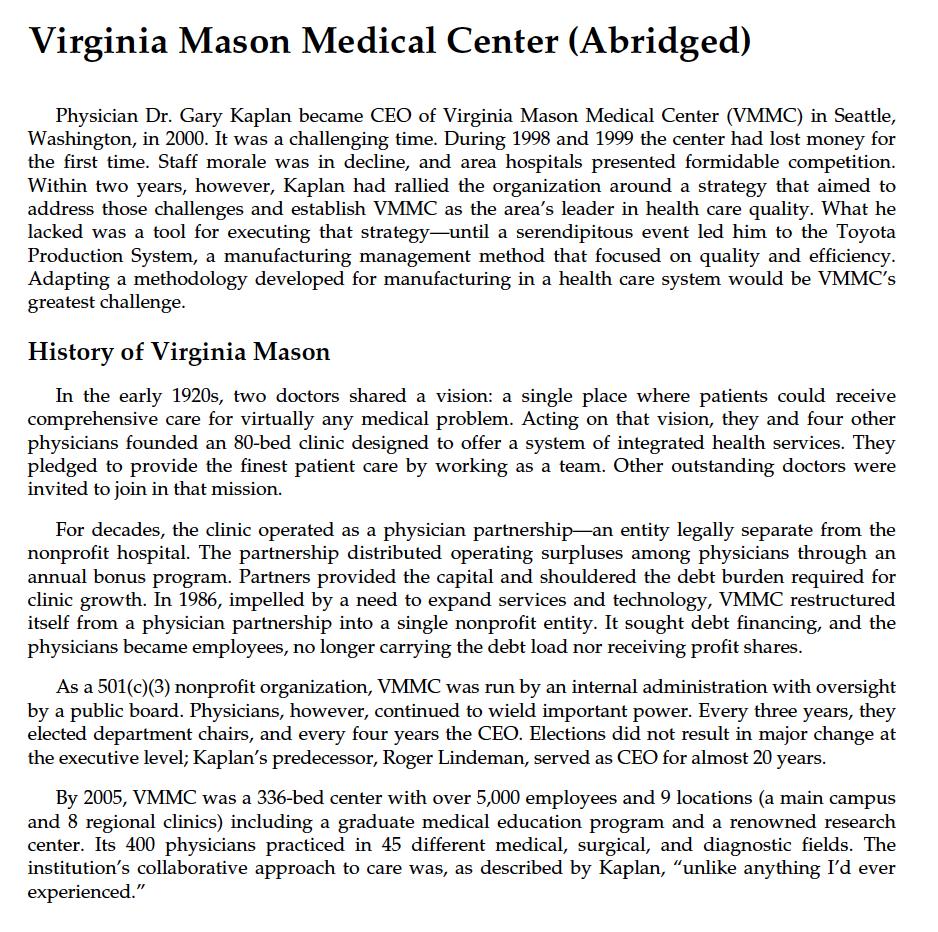

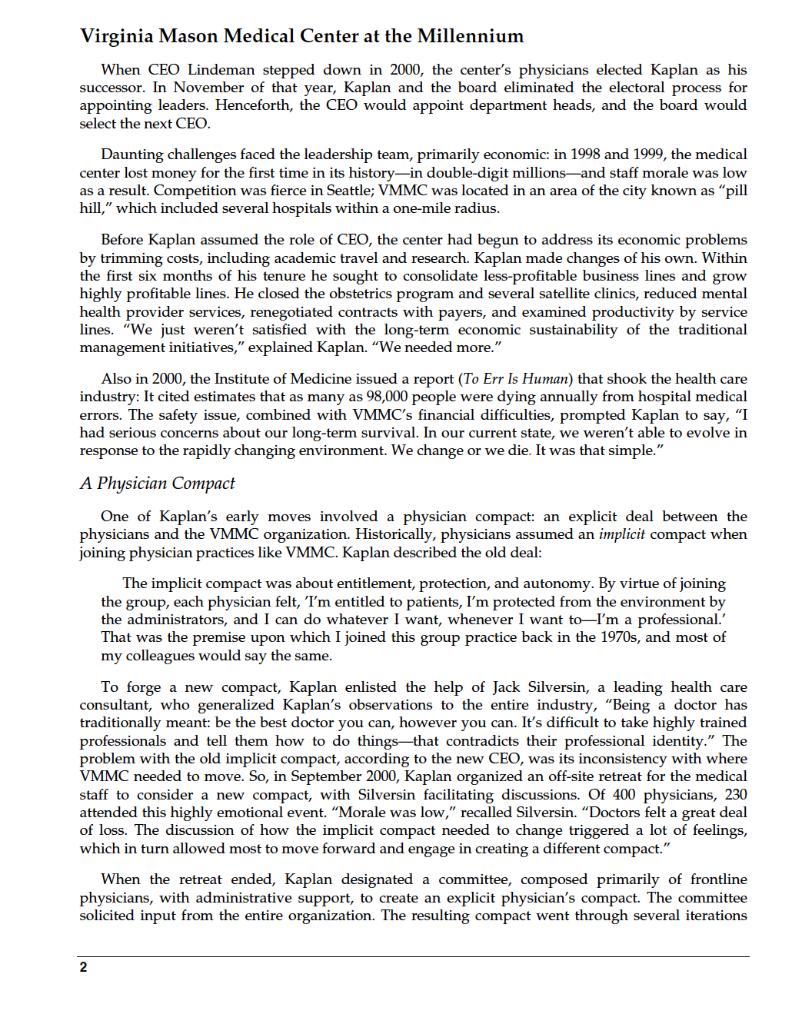

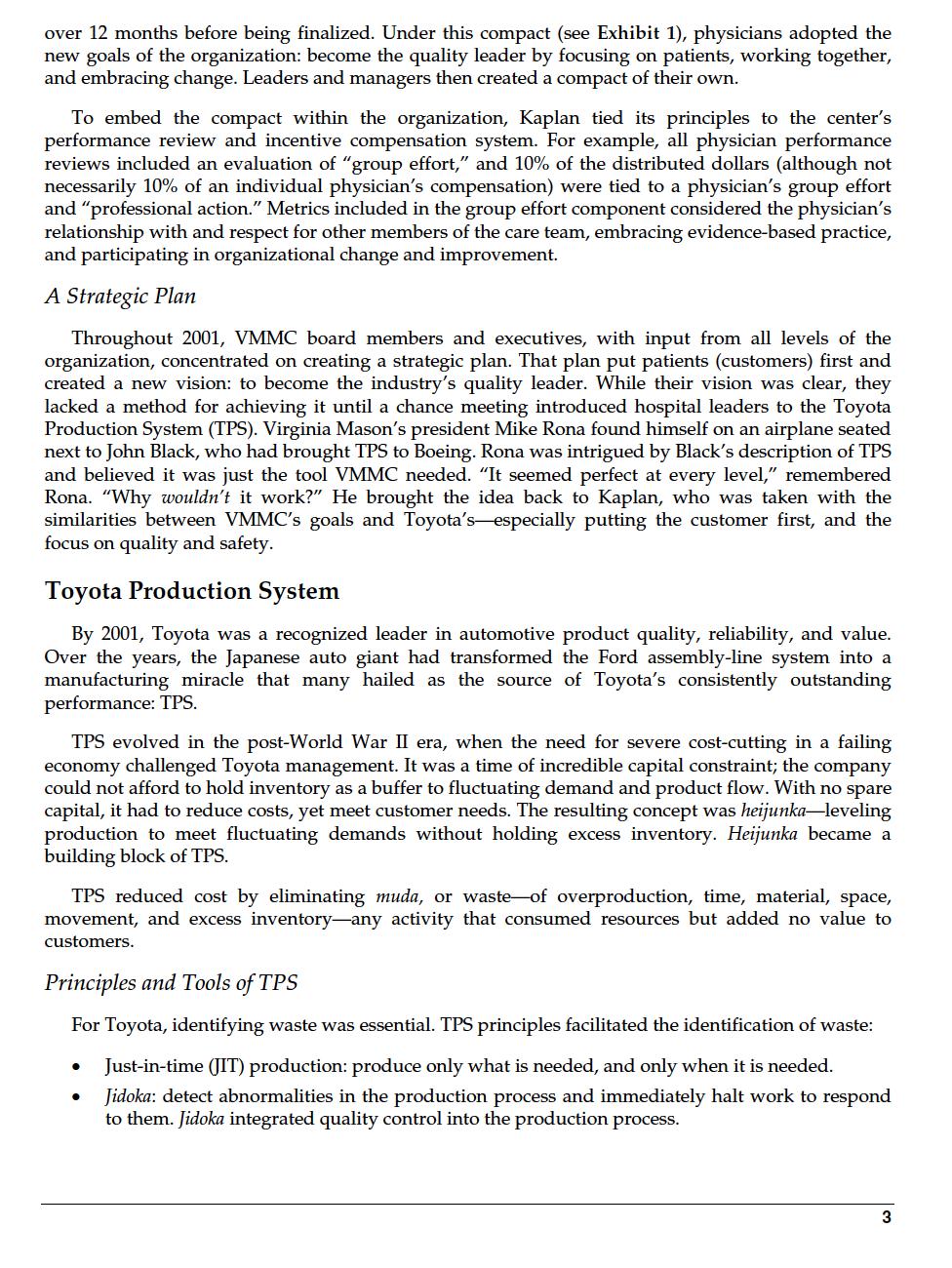

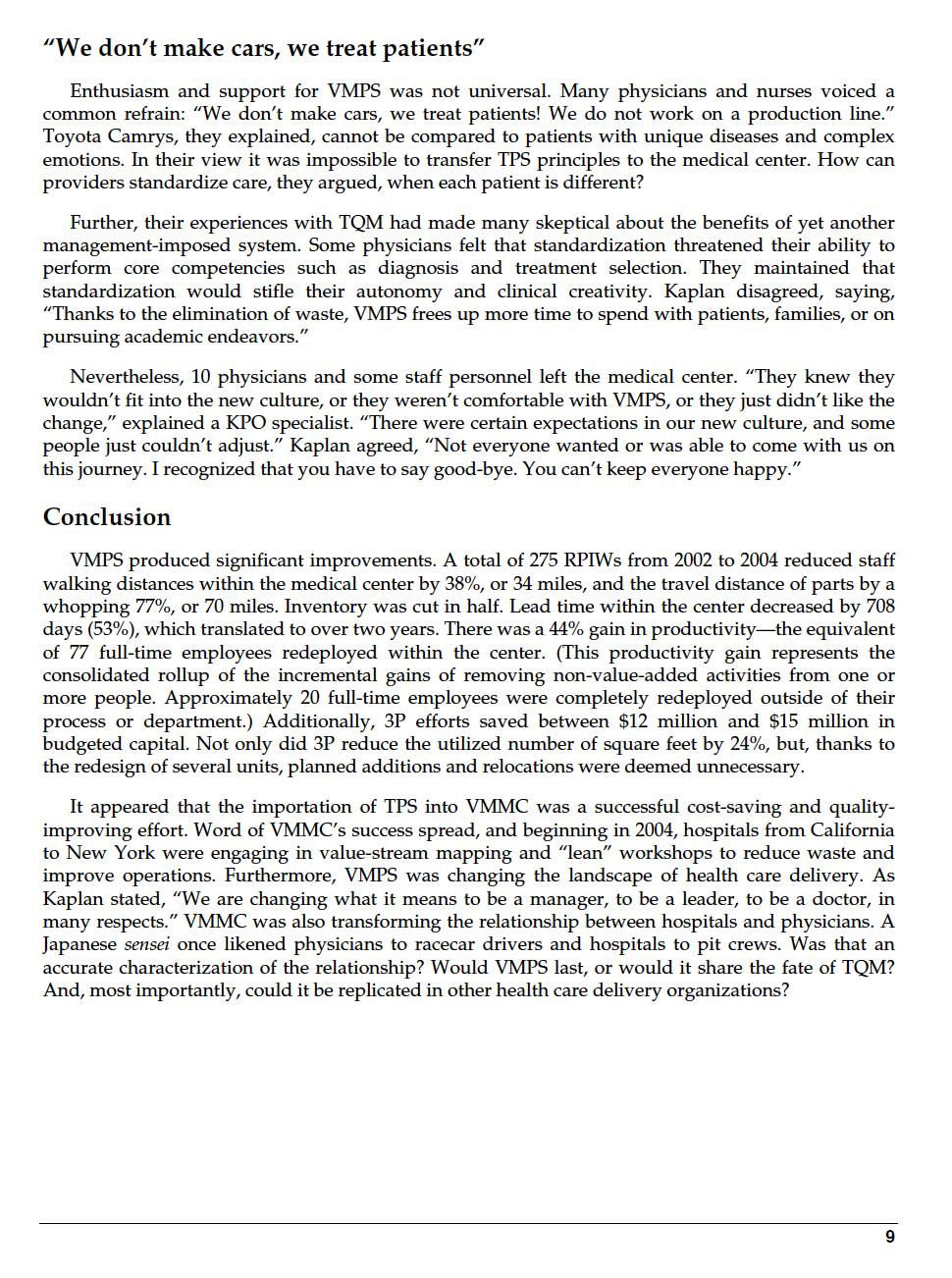

Virginia Mason Medical Center (Abridged) Physician Dr. Gary Kaplan became CEO of Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) in Seattle, Washington, in 2000. It was a challenging time. During 1998 and 1999 the center had lost money for the first time. Staff morale was in decline, and area hospitals presented formidable competition. Within two years, however, Kaplan had rallied the organization around a strategy that aimed to address those challenges and establish VMMC as the area's leader in health care quality. What he lacked was a tool for executing that strategy-until a serendipitous event led him to the Toyota Production System, a manufacturing management method that focused on quality and efficiency. Adapting a methodology developed for manufacturing in a health care system would be VMMC's greatest challenge. History of Virginia Mason In the early 1920s, two doctors shared a vision: a single place where patients could receive comprehensive care for virtually any medical problem. Acting on that vision, they and four other physicians founded an 80-bed clinic designed to offer a system of integrated health services. They pledged to provide the finest patient care by working as a team. Other outstanding doctors were invited to join in that mission. For decades, the clinic operated as a physician partnership an entity legally separate from the nonprofit hospital. The partnership distributed operating surpluses among physicians through an annual bonus program. Partners provided the capital and shouldered the debt burden required for clinic growth. In 1986, impelled by a need to expand services and technology, VMMC restructured itself from a physician partnership into a single nonprofit entity. It sought debt financing, and the physicians became employees, no longer carrying the debt load nor receiving profit shares. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, VMMC was run by an internal administration with oversight by a public board. Physicians, however, continued to wield important power. Every three years, they elected department chairs, and every four years the CEO. Elections did not result in major change at the executive level; Kaplan's predecessor, Roger Lindeman, served as CEO for almost 20 years. By 2005, VMMC was a 336-bed center with over 5,000 employees and 9 locations (a main campus and 8 regional clinics) including a graduate medical education program and a renowned research center. Its 400 physicians practiced in 45 different medical, surgical, and diagnostic fields. The institution's collaborative approach to care was, as described by Kaplan, "unlike anything I'd ever experienced." Virginia Mason Medical Center at the Millennium When CEO Lindeman stepped down in 2000, the center's physicians elected Kaplan as his successor. In November of that year, Kaplan and the board eliminated the electoral process for appointing leaders. Henceforth, the CEO would appoint department heads, and the board would select the next CEO. Daunting challenges faced the leadership team, primarily economic: in 1998 and 1999, the medical center lost money for the first time in its history-in double-digit millions and staff morale was low as a result. Competition was fierce in Seattle; VMMC was located in an area of the city known as "pill hill," which included several hospitals within a one-mile radius. Before Kaplan assumed the role of CEO, the center had begun to address its economic problems by trimming costs, including academic travel and research. Kaplan made changes of his own. Within the first six months of his tenure he sought to consolidate less-profitable business lines and grow highly profitable lines. He closed the obstetrics program and several satellite clinics, reduced mental health provider services, renegotiated contracts with payers, and examined productivity by service lines. "We just weren't satisfied with the long-term economic sustainability of the traditional management initiatives," explained Kaplan. "We needed more." Also in 2000, the Institute of Medicine issued a report (To Err Is Human) that shook the health care industry: It cited estimates that as many as 98,000 people were dying annually from hospital medical errors. The safety issue, combined with VMMC's financial difficulties, prompted Kaplan to say, "I had serious concerns about our long-term survival. In our current state, we weren't able to evolve in response to the rapidly changing environment. We change or we die. It was that simple." A Physician Compact One of Kaplan's early moves involved a physician compact: an explicit deal between the physicians and the VMMC organization. Historically, physicians assumed an implicit compact when joining physician practices like VMMC. Kaplan described the old deal: The implicit compact was about entitlement, protection, and autonomy. By virtue of joining the group, each physician felt, I'm entitled to patients, I'm protected from the environment by the administrators, and I can do whatever I want, whenever I want to-I'm a professional. That was the premise upon which I joined this group practice back in the 1970s, and most of my colleagues would say the same. To forge a new compact, Kaplan enlisted the help of Jack Silversin, a leading health care consultant, who generalized Kaplan's observations to the entire industry, "Being a doctor has traditionally meant: be the best doctor you can, however you can. It's difficult to take highly trained professionals and tell them how to do things that contradicts their professional identity." The problem with the old implicit compact, according to the new CEO, was its inconsistency with where VMMC needed to move. So, in September 2000, Kaplan organized an off-site retreat for the medical staff to consider a new compact, with Silversin facilitating discussions. Of 400 physicians, 230 attended this highly emotional event. "Morale was low," recalled Silversin. "Doctors felt a great deal of loss. The discussion of how the implicit compact needed to change triggered a lot of feelings, which in turn allowed most to move forward and engage in creating a different compact." When the retreat ended, Kaplan designated a committee, composed primarily of frontline physicians, with administrative support, to create an explicit physician's compact. The committee solicited input from the entire organization. The resulting compact went through several iterations 2 over 12 months before being finalized. Under this compact (see Exhibit 1), physicians adopted the new goals of the organization: become the quality leader by focusing on patients, working together, and embracing change. Leaders and managers then created a compact of their own. To embed the compact within the organization, Kaplan tied its principles to the center's performance review and incentive compensation system. For example, all physician performance reviews included an evaluation of "group effort," and 10% of the distributed dollars (although not necessarily 10% of an individual physician's compensation) were tied to a physician's group effort and "professional action." Metrics included in the group effort component considered the physician's relationship with and respect for other members of the care team, embracing evidence-based practice, and participating in organizational change and improvement. A Strategic Plan Throughout 2001, VMMC board members and executives, with input from all levels of the organization, concentrated on creating a strategic plan. That plan put patients (customers) first and created a new vision: to become the industry's quality leader. While their vision was clear, they lacked a method for achieving it until a chance meeting introduced hospital leaders to the Toyota Production System (TPS). Virginia Mason's president Mike Rona found himself on an airplane seated next to John Black, who had brought TPS to Boeing. Rona was intrigued by Black's description of TPS and believed it was just the tool VMMC needed. "It seemed perfect at every level," remembered Rona. "Why wouldn't it work?" He brought the idea back to Kaplan, who was taken with the similarities between VMMC's goals and Toyota's especially putting the customer first, and the focus on quality and safety. Toyota Production System By 2001, Toyota was a recognized leader in automotive product quality, reliability, and value. Over the years, the Japanese auto giant had transformed the Ford assembly-line system into a manufacturing miracle that many hailed as the source of Toyota's consistently outstanding performance: TPS. TPS evolved in the post-World War II era, when the need for severe cost-cutting in a failing economy challenged Toyota management. It was a time of incredible capital constraint; the company could not afford to hold inventory as a buffer to fluctuating demand and product flow. With no spare capital, it had to reduce costs, yet meet customer needs. The resulting concept was heijunka-leveling production to meet fluctuating demands without holding excess inventory. Heijunka became a building block of TPS. TPS reduced cost by eliminating muda, or waste of overproduction, time, material, space, movement, and excess inventory-any activity that consumed resources but added no value to customers. Principles and Tools of TPS For Toyota, identifying waste was essential. TPS principles facilitated the identification of waste: Just-in-time (JIT) production: produce only what is needed, and only when it is needed. Jidoka: detect abnormalities in the production process and immediately halt work to respond to them. Jidoka integrated quality control into the production process. 3 Initial use of TQM principles and tools in health care was restricted to "hotel functions"-billing, laboratory turnaround time, patient transport, and so on. However, by the early 1990s they were being applied to clinical processes as well.4 Despite initial enthusiasm, skepticism about TQM grew as evidence accumulated that U.S. health care quality was not improving. A national survey of health care managers found that none could identify a health care institution that had fundamentally improved its performance using these methods. Moreover, evidence of improvement was lacking in clinical journals. Explanations for this outcome differed: poor implementation; a lack of senior leadership commitment and skill; a lack of physician involvement in hospital governance (most hospitals' physicians were independent providers, not direct employees). One argued that hospitals should begin implementation with administrative rather than clinical projects in order to avoid physician revolt; others argued that clinical projects early in implementation could produce physician champions. Some researchers contended that while early adopters of TQM customized it to make efficiency gains, later adopters simply implemented normative TQM models to keep up with the mainstream. Whether an organization implemented some or all TQM principles and techniques, however, was not found to predict performance improvement. Rather, a culture supporting quality improvement work was found to be more important than the use of any specific tools. Other researchers proposed that TQM was conceptually ill-suited to health care settings. They argued that TQM's emphasis on top management's control over work processes and its presumption of rational decision making was, by definition, ill-suited because these two characteristics were seldom present in health care organizations. TPS had also been applied in a health care setting. Early results at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center were encouraging: a reduction in patient waiting time, less time spent on patient registration and the assembly of medical charts, improved supplies availability, and reduced rates of nosocomial infection.5 Virginia Mason Production System (VMPS) TPS appeared to be the method Virginia Mason had been seeking to implement its strategic plan. Other alternatives had failed to garner much support. VMMC had utilized TQM in the 1990s, but its concepts had gained little traction. One executive described TQM as "a bunch of administrative teams meeting, deciding on new processes or better ways of doing things, and handing it down to the rest of us." Administrators had also investigated Six Sigma, but objected to its allowance of a "defect rate." "Saf and perfection are paramount," explained manager. "Even a small defect rate is not acceptable. We're talking about patients' lives here." Kaplan and Rona encountered little resistance to TPS from the board, whose members were impressed by Toyota's long history of safety, quality, customer and employee satisfaction, and financial success. In 2002, senior VMMC executives visited Toyota in Japan. Armed with Toyota's principles, leadership at the medical center began to envision a Virginia Mason Production System (VMPS). No Layoffs Conventional wisdom held that improved productivity would result in layoffs. Thus, VMMC anticipated some employee resistance. To neutralize resistance to the new system, VMMC instituted a no-layoff policy under which people would be trained to move to other areas when their units improved efficiency to the point of being overstaffed. Kaplan described some of the challenges of this policy: 5 You can't redeploy an operating room nurse and make her into an ultrasound technician. One great example of redeployment was in the audiology department-we did a workshop and discovered we had two-and-a-half too many audiologists. These are highly trained professionals with advanced degrees! We ended up redeploying one of our best audiologists as a project manager in the operating room, with equal pay, and she's very happy there. VMPS Tools VMPS depended on the use of specific tools borrowed from TPS and tailored to fit the health care model. Value-stream mapping Value-stream mapping is a method of visually mapping the flow of information and materials through all production steps. As applied, value-stream mapping was a simple flow chart with associated medical-center metrics. Kaplan saw value-stream mapping as the foundation of VMPS. "Understanding the work is critical," he said. "Unless you understand the steps, you cannot see the waste, you cannot see the opportunity, you cannot see the defects." At VMMC, early value-stream mapping encompassed patient check-in and visits, the flow of equipment, and inventory (Exhibit 2). Eventually, all departments engaged in value-stream mapping. RPIW Value-stream mapping was the first step in a rapid process improvement workshop (RPIW) a five-day event designed to eliminate waste, improve processes, and increase both efficiency and productivity in participating units. As legendary TPS guru Taiichi Ohno once said, "You can't improve a process until you have a process."6 Thus, each RPIW team defined an existing process and set a target for a new one. The next few days were spent observing, measuring, and brainstorming the existing process. On the fourth day, the team established new or improved standard work, and on the fifth day "reported out" to the organization. RPIWs measured specific tasks, such as staff walking distance, and inventory turns. Task quality was also measured. Standard tools were utilized in each RPIW, such as a target progress report, to track metrics. From 2002 to 2005, over 350 RPIWs were undertaken, often, for the sake of continuous improvement, on the same targets (see Exhibit 3 for RPIWs per year). Actionable items typically resulted from PRIWS. For example, the hematology and oncology department discovered during an RPIW that 49% of its patients were not roomed by their scheduled appointment time. This led to a new patient rooming process, complete with a visual control board for monitoring patient, room, and provider status. 5S 5S, a visual system for organizing physical space, stood for Sort, Simplify, Sweep, Standardize, and Self-Discipline. A clean and orderly space enhanced quality and productivity because less time was wasted searching for tools, and problems were more salient. 3P 3P-Production, Preparation, Process is an improvement strategy used to redesign space according to flow. VMMC designated "seven flows of medicine": patients, providers, medications, supplies, equipment, information, and instruments. Using 3P, people examined ways to improve service delivery, introduce new services, and complement process design changes. 3Ps throughout the medical center saved over $10 million in capital budgeted funds. One example of 3P involved the hematology and oncology unit, where patients, doctors, and nurses collaborated with architects to redesign the physical layout of treatment rooms, offices, and the waiting room. The final product was a circular space, with treatment rooms on the outside and exam rooms, offices, nurse stations, and administration arranged to maximize communication while reducing travel time. In the same amount of space, they increased the number of daily patient visits from 120 to 188-a 57% increase and reduced patient travel per visit from 1,600 feet to 375 feet-a 6 76% decrease. A new on-site pharmacy and an improved lab delivery system reduced wait times from 2 hours to 20-30 minutes and 20 minutes 1 minute, respectively. Every detail was considered according to 3P. For example, the unit contained three medication refrigerators; in each refrigerator, medicines were located in the exact same spots. Everyday lean This tool encouraged employees at every level to creatively reduce waste and add value for patients by finding areas for improvement, innovating solutions, testing solutions on a small scale, and measuring the effects. An everyday lean idea "form" standardized the process of submitting proposals and implementing successful solutions. Monthly contests recognized the top three employee ideas. Judges reviewed ideas based on applicability, ease of implementation, and how well the standard process was followed. Between June and September 2005, employees suggested 87 lean ideas, 80% of which were implemented. Patient safety alert system (PSA) PSA resulted from a Japanese factory visit where the andon cord was witnessed in action. VMMC's PSA system empowered all employees to "pull the cord" whenever a safety hazard or mistake was identified. Senior leaders would then address the root cause of the problem. For example, a dermatology assistant prepared two syringes for a surgical patient. When the physician injected the first syringe, the patient reported discomfort and a lack of numbness in the surgical site. Suspecting that the medication mix in the syringe was incorrect, the physician aborted the procedure, informed the patient of the error, called the pharmacy for advice, and sent the patient to observation. The chief of medicine, the vice president of quality and compliance, and the CEO were then notified. A buddy system was initiated to verify the appropriate mixing of medications, and an employee team began to analyze and eliminate the process defects that caused the error. VMMC undertook an average of 32 PSAs per month, and each issue took 48 hours to two weeks to resolve. Kaplan gave this example of a PSA involving a "retained sponge," a surgical mistake: When that [mistake] was identified, we took that surgeon, the whole team, and the procedure offline until we understood the root cause of that problem. That is tough to do-it is productive time, it is economics, it is reputation, it is a lot of things, and so the onus was on us. And that root cause analysis was complete in 48 hours. Despite its efforts to "mistake-proof" its operations, however, VMMC experienced what in health care was known as a sentinel event-an avoidable mistake that becomes a turning point for the organization. In 2004 three years into the VMPS program-a patient in the interventional radiology department received an injection of chlorhexidine (an antiseptic solution) instead of a nontoxic image dye used to view the arteries. The two solutions looked exactly the same and were sitting unlabeled on the same tray. The patient died as a result of this tragic mistake, shocking the organization. Believing that highlighting the event could prevent its recurrence, the administration quickly sent out a center-wide memo explaining the situation and posted an apology. Kaplan recalled the reaction of the one 20-year veteran physician of VMMC: "She stopped me in the hallway and said, 'It's so sad and so ironic that at this time in our history, when we're required to focus relentlessly on safety, such a tragedy can still occur. No matter how much we do, it's still a journey."" Bundles In 2004, VMMC sought best practices from the medical literature and from Institute for Health care Improvement (IHI) publications. It then instituted "bundles" (collections of best practices) into VMPS. Best practices were discovered through scientific experimentation and were widely agreed to be preferred methods. Bundles adopted at VMMC included specific steps to prevent ventilator-acquired pneumonia, surgical-site infection, and central-line infection. For example, ventilators were known to occasionally induce pneumonia in patients. Various factors were identified 7 as increasing the risk of ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP), and the bundles aimed to eliminate them. Dr. Mike Westley, section head of critical care, explained: We use the principles of VMPS to reliably get evidence-based VAP bundles to every patient. It's about self-checks, successive checks, redundancy, and documentation. For example, with bed elevation [a best practice] we don't leave it up to one person. The respiratory therapists check it every three hours, nurses check it every two hours, and we document it. Nurses have told me, if we don't document it, we don't do it. In 2002, VMMC experienced 34 cases of ventilator-acquired pneumonia, at an estimated total cost of $500,000. By 2005, the cases had been reduced to only one, at a cost of $15,000. VMPS Infrastructure To support the massive undertaking of VMPS implementation, the medical center created an infrastructure designed around VMPS operations and kaizen promotion offices (KPOs). KPOs were responsible for overseeing, leading, and coaching units through RPIWS, as well as facilitating everyday lean. The first generation of VMPS infrastructure designated only one KPO; it was responsible for the organization and implementation of all RPIWs and VMPS tools. As a result, early RPIWs often included overambitious targets or attempts to tackle too many targets in a single workshop. The KPO found itself stretched too thin. In early 2005, however, the system expanded to three KPOs, each with six full-time staffers. This increase in KPO support resulted in RPIW goals that were better aligned with organizational goals, the creation and tracking of explicit metrics, and accountability for implementation and sustained results. Two operations managers became VMPS specialists; they oversaw the training and education of all 5,000 VMMC employees. Educational courses included an introduction to VMPS and everyday lean, and how-to courses on value-stream mapping and mistake-proofing. The operations managers also facilitated the planning and development of RPIWs, oversaw data collection and analyses, and provided support for 3P redesign. In addition, VMMC funded two trips annually to Toyota's head office and to factories in Japan. There, senior executives, physicians, and nurses, observed and worked on a shop floor at Hitachi. Kaplan, who led every trip, told this story about a reluctant physician participant: 8 When I asked one of our surgeons to go to Japan in 2003, he refused. A year later he changed his mind because he'd heard that it was value-added time. So he is on the assembly line in Japan, and I send the team out to get measurements of their workers so that we can plot the work and find the waste. And he came running back and said, "I can't get any measurements. I can't clock it." I asked, "Why not?" And he answered, "Because the operator does it differently every single time. There is no standard work!" And there was the teaching point: because this person did it differently each time, the surgeon couldn't possibly measure the work; and if you can't measure it, you can't improve it. That was very powerful. Overall, VMMC dedicated 20 full-time employees (18 KPO staffers plus two central operations managers) to the planning, implementation, and maintenance of VMPS. All were redeployed from other roles. The financial commitment to VMPS was large, but administrators thought that financial gains through improved efficiency outweighed the added labor costs. In the first two years of VMPS, the medical center's margins improved significantly. RPIWs and everyday lean ideas yielded higher efficiency improvements. "We don't make cars, we treat patients" Enthusiasm and support for VMPS was not universal. Many physicians and nurses voiced a common refrain: "We don't make cars, we treat patients! We do not work on a production line." Toyota Camrys, they explained, cannot be compared to patients with unique diseases and complex emotions. In their view it was impossible to transfer TPS principles to the medical center. How can providers standardize care, they argued, when each patient is different? Further, their experiences with TQM had made many skeptical about the benefits of yet another management-imposed system. Some physicians felt that standardization threatened their ability to perform core competencies such as diagnosis and treatment selection. They maintained that standardization would stifle their autonomy and clinical creativity. Kaplan disagreed, saying, "Thanks to the elimination of waste, VMPS frees up more time to spend with patients, families, or on pursuing academic endeavors." Nevertheless, 10 physicians and some staff personnel left the medical center. "They knew they wouldn't fit into the new culture, or they weren't comfortable with VMPS, or they just didn't like the change," explained a KPO specialist. "There were certain expectations in our new culture, and some people just couldn't adjust." Kaplan agreed, "Not everyone wanted or was able to come with us on this journey. I recognized that you have to say good-bye. You can't keep everyone happy." Conclusion VMPS produced significant improvements. A total of 275 RPIWs from 2002 to 2004 reduced staff walking distances within the medical center by 38%, or 34 miles, and the travel distance of parts by a whopping 77%, or 70 miles. Inventory was cut in half. Lead time within the center decreased by 708 days (53%), which translated to over two years. There was a 44% gain in productivity-the equivalent of 77 full-time employees redeployed within the center. (This productivity gain represents the consolidated rollup of the incremental gains of removing non-value-added activities from one or more people. Approximately 20 full-time employees were completely redeployed outside of their process or department.) Additionally, 3P efforts saved between $12 million and $15 million in budgeted capital. Not only did 3P reduce the utilized number of square feet by 24%, but, thanks to the redesign of several units, planned additions and relocations were deemed unnecessary. It appeared that the importation of TPS into VMMC was a successful cost-saving and quality- improving effort. Word of VMMC's success spread, and beginning in 2004, hospitals from California to New York were engaging in value-stream mapping and "lean" workshops to reduce waste and improve operations. Furthermore, VMPS was changing the landscape of health care delivery. As Kaplan stated, "We are changing what it means to be a manager, to be a leader, to be a doctor, in many respects." VMMC was also transforming the relationship between hospitals and physicians. A Japanese sensei once likened physicians to racecar drivers and hospitals to pit crews. Was that an accurate characterization of the relationship? Would VMPS last, or would it share the fate of TQM? And, most importantly, could it be replicated in other health care delivery organizations? 9 Case Study - Background Reading - Strategic Management - Banks The CEO of St. Sebastian Health System, a moderate-sized hospital system in a mid-sized, Midwest city has hired you to help turn things around. The CFO is projecting an $8.9 million operating loss this year, which will be more than offset by non-operating income. However, the board has made it clear that the situation must improve. If the system cannot produce a positive operating margin in 2022, someone else is going to be the CEO. The CEO and CFO have asked you to recommend strategic approaches to selling their services in the community that will help turn the financial ship around. Your Health System St. Sebastian is a community-based health system. The senior management team has an average tenure of 17 years. The exception is the Chief Medical Officer (CMO). She has been in her position for two years and is the fourth CMO in that role in the past ten years. The CEO and COO have each been in their current roles for ten years. The system is comprised of the following: 1. Two large, acute care hospitals 2. Two long term care facilities 3. Two skilled nursing facilities 4. One long-term acute-care hospital (LTAC) 5. Four geographically distributed outpatient centers 6. Four Urgent Care Centers 7. Two free-standing ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) 8. A 400 member employed physician group that includes 180 Primary Care Providers (PCPs). All 28 PCP practices are certified Level III Patient Centered Medical Homes by NCQA. The remainder of the 1,000 member medical staff is generally comprised of large, independent groups who have varying degrees of 'loyalty' to the system. The Radiology and Emergency groups, for example do 100% of their work at St. Sebastian and have no ownership of any outside facilities. The Gastroenterology group, on the other hand, does work at the hospital, but also owns their own, freestanding endoscopy center. The orthopedic group does 75% of their work at St. Sebastian, but maintains privileges at other facilities. They do not own their own ASC. In the current year, St. Sebastian is projecting 221,700 patient visits (combined IP and OP) with an average cost per visit of $1,775. They have an avera charge per visit of $4,600. Over the past ten years, St. Sebastian has been active in pursuing a number of different strategic projects including: 1. They have established 'clinical institutes' in cardiovascular, orthopedic, oncology, maternity and neurologic care. Each of these has been built through a co-management agreement between the system and the internal or external physician group who would be most logical. Each institute is led by a dyad of an administrator and medical director. 2. Five years ago, they consolidated maternity programs to one facility, a move that justified investing in a Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) 3. They have established a research division in the hopes of working with national pharmaceutical companies and/or tertiary care hospitals in the Midwest. 4. They have established a Physician Hospital Organization (PHO) and intend to become an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) that can participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and/or enter into global risk contracts with third party payers. The PHO is currently evaluating whether or not they should purchase an insurance license so that they could offer commercial, Medicare Advantage and Managed Medicaid insurance products. 5. They have established a Business Health division to service the corporate health needs of the employers in the region. This would include things like EAP programs, on-site wellness, drug screening, on-site clinics, etc. This division also recently built two large, full-service fitness centers. The competition - The community is currently served by three other major health providers: 1. Mercy is the competitor acute care system in town and has two hospitals and various outpatient centers. They have not been active in physician employment - they employ a group of 60 PCPs, but no specialists. Similarly, they have not been engaged in 'branching out' with different strategic initiatives, preferring instead to focus on cost efficient care. They do not have clinical institutes, research divisions, a PHO or a Business Health division. They have 228,500 visits per year, with an average cost of $1,450 per visit and an average charge of $4,450. 2. General Pediatric is a pediatric teaching hospital. Five years ago, they signed an affiliation agreement with Johns Hopkins to gain access to clinical and research capabilities that would have been beyond their reach, given their size. They employee essentially all of the pediatric subspecialists and have a PHO, which includes 75% of the region's primary care pediatricians. They will have 202,000 visits this year, with an average cost of $2,050 per visit and an average charge of $4,950 per visit. 3. General University is an adult teaching hospital affiliated with the local university's medical school. They staff the region's free-care clinics and historically, have been the region's hospital for indigent/uninsured patients. They are the region's Level I trauma center and are well regarded for intensive services like trauma, stroke and cancer care. However, their location and reputation for taking indigent patients means that they are not preferred for 'normal' medical care by commercially insured or Medicare patients. Besides the community health centers, they own an inpatient rehab hospital, but not other facilities. They have explored affiliations with national leaders in academic medicine, but so far have not signed any such agreements. They see 185,000 visits per year with an average cost of $1,825 and an average charge of $5,600 per visit. There are no other hospitals currently operating, though there are 23 skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and 3 inpatient rehab facilities throughout the region. They are independent actors and for the most part are struggling to stay profitable. There are several single-specialty physician groups who operate ambulatory surgery centers and one chain of independent diagnostic treatment facilities (IDTFs). Three years ago, there was a significant change in the state government, and that resulted in the long-time Certificate of Need (CON) program being all but scrapped (Skilled Nursing Facilities are still heavily regulated). Several for-profit hospital companies have recently done some analysis around entering your market, but have not done so yet. The Community - The community is a Midwest city and surrounding suburbs in the midst of a transition from a manufacturing employment base, which unfortunately accelerated with the 2008 economic downturn. The hospitals have seen this over the past several years in a tightening of benefits offered by local employers. Benefits continue to be offered, but increasingly are likely to have a significant deductible associated with them. Unemployment has been above the national average and is projected to remain that way. This means that the average wage in the region is actually below where it was in 2008, when the last recession hit. The number of Medicare-age residents are projected to rise over the next 10-20 years, while working age patients are projected to stay flat or fall slightly. Similarly, birth rates are expected to fall slightly over the coming decade. The community is 60 miles south, 45 miles east and 50 miles north of other, similarly sized cities. Until 20 years ago, that made this city effectively an island unto itself. Increasingly, however, the suburbs of each of these communities have become very close to each other. As that has happened, providers in each community have followed and established practice sites and free-standing outpatient centers. The payers - The community has a normal looking mix of Commercial, Medicare and Medicaid patients. Because the state's governor was fiercely against the Affordable Care Act, the Medicaid expansion that happened in other states hasn't happened here. Thus, the community also has a sizable population without insurance today. As you'd expect, different hospitals see a different mix of these patients. The local health council was able to provide you with the most recent year's payer mix by hospital - below: Patient visits Mercy St. Sebastian Gen. Pediatric Gen. University Community Total Commercial 82,000 100,500 71,000 65,000 318,500 Medicare 104,000 100,200 3,500 46,000 253,700 Medicaid 22,000 12,500 112,500 47,500 194,500 Uninsured/ Self-pay 20,500 8,500 15,000 26,500 70,500 Reimbursement - the CFO was able to supply you with their best estimate for what various payers are reimbursing for services. In general, the commercial plans are paying 50% of charges, regardless of location, except at General Pediatric. There, the monopoly on pediatric services has allowed them to negotiate rates of 80% of charge, but only for the commercial plans. Medicare currently pays 30% of charges at all hospitals, and Medicaid pays 25% of charges everywhere. Uninsured patients are generally paying 2% of charges. Review the reading "Virginia Mason Medical Center (Abridged)" and consider the facts of the Case Study. 1. What is your view of the "people are not cars" debate? 2. Is Kaplan's approach transferrable to St. Sebastian? Can other US healthcare organizations benefit from this approach? If so, explain why. If not, explain why not? 3. Based on long-range financial planning, what would you advise St. Sebastian to do over the next 5 years, and how would you prioritize those recommendations?

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.33 Rating (147 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started