Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

What are the key leadership qualities that you have seen come to life in the case study that helped this organization through the change process?

What are the key leadership qualities that you have seen come to life in the case study that helped this organization through the change process?

What leadership qualities do you feel are important to exhibit during a change process? Why?

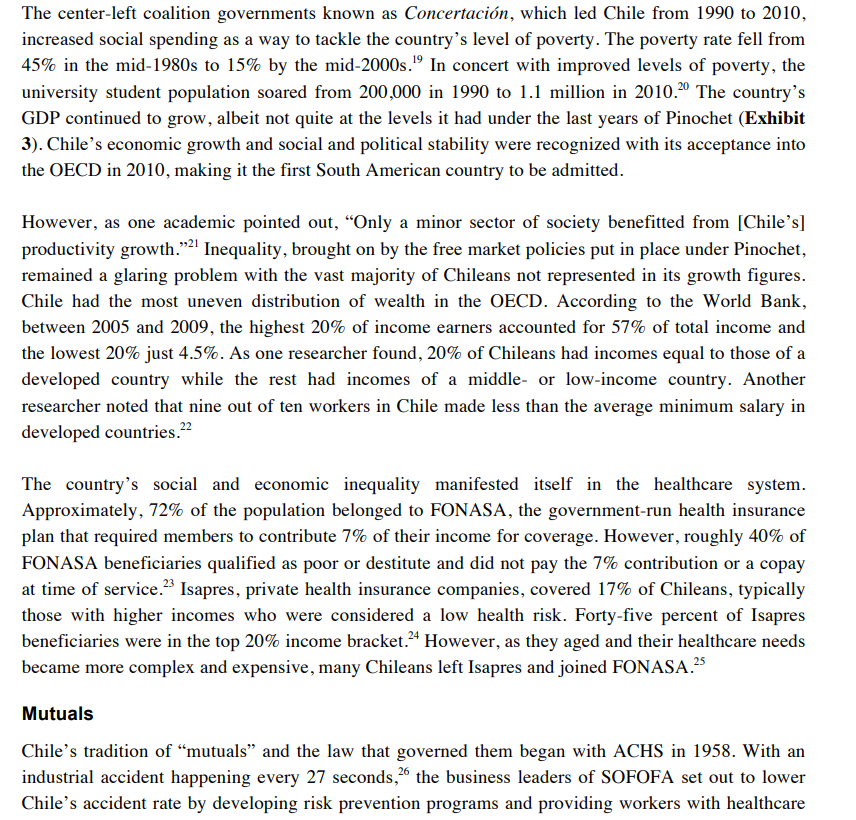

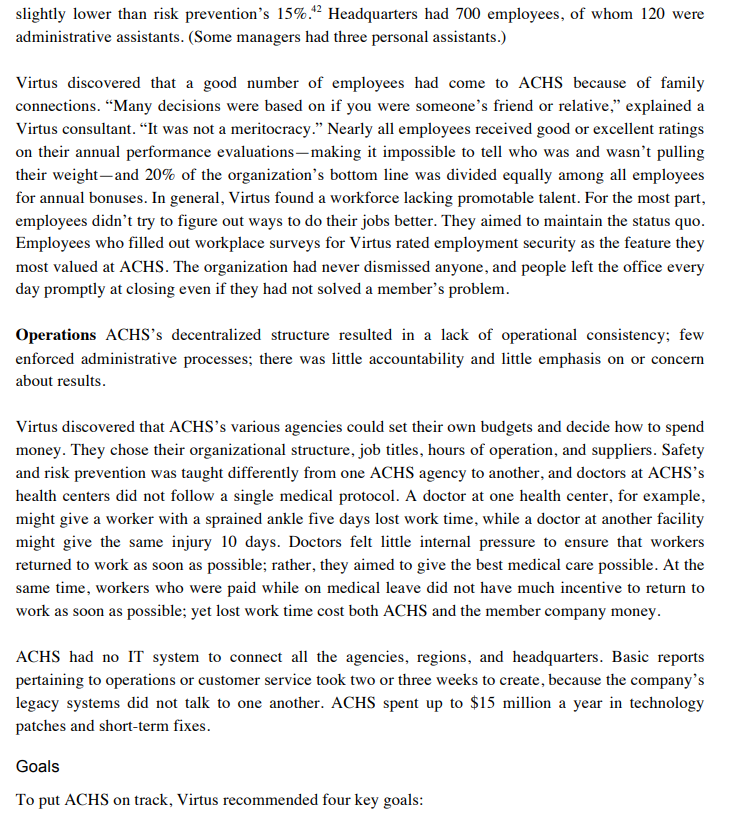

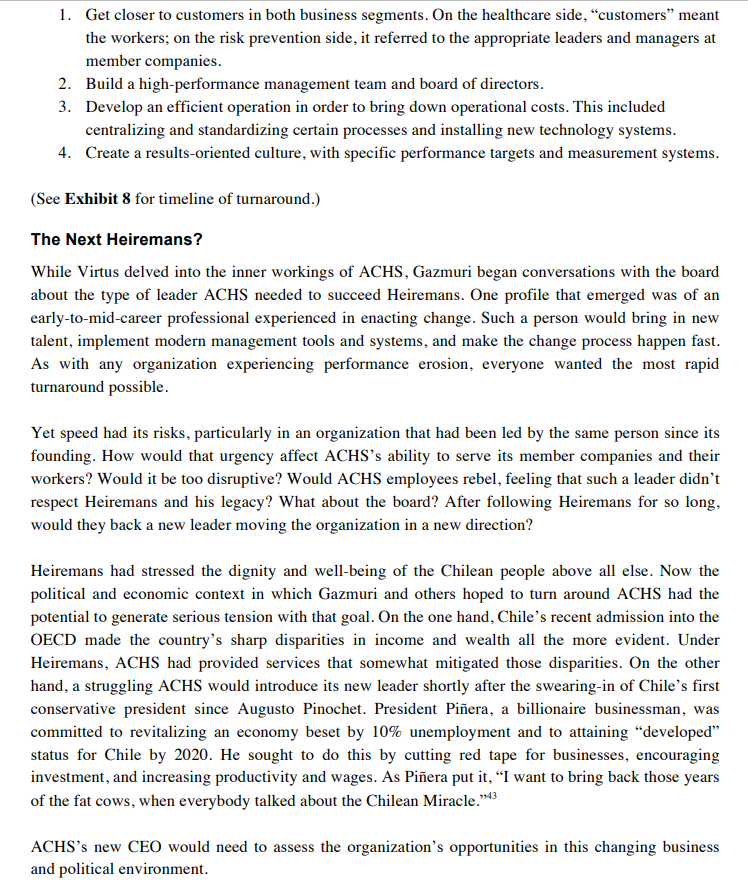

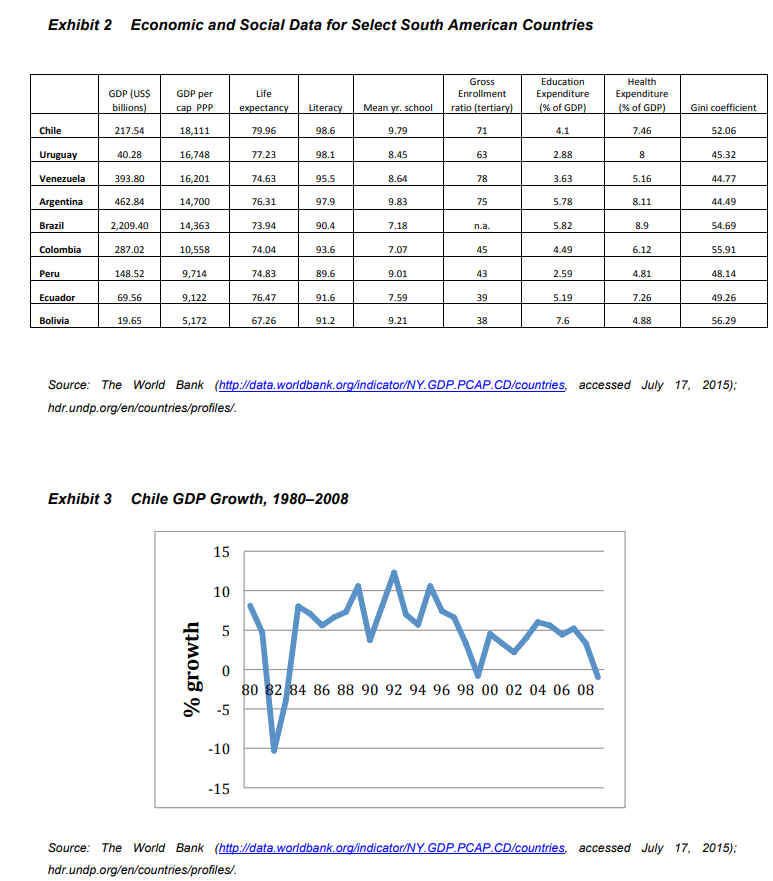

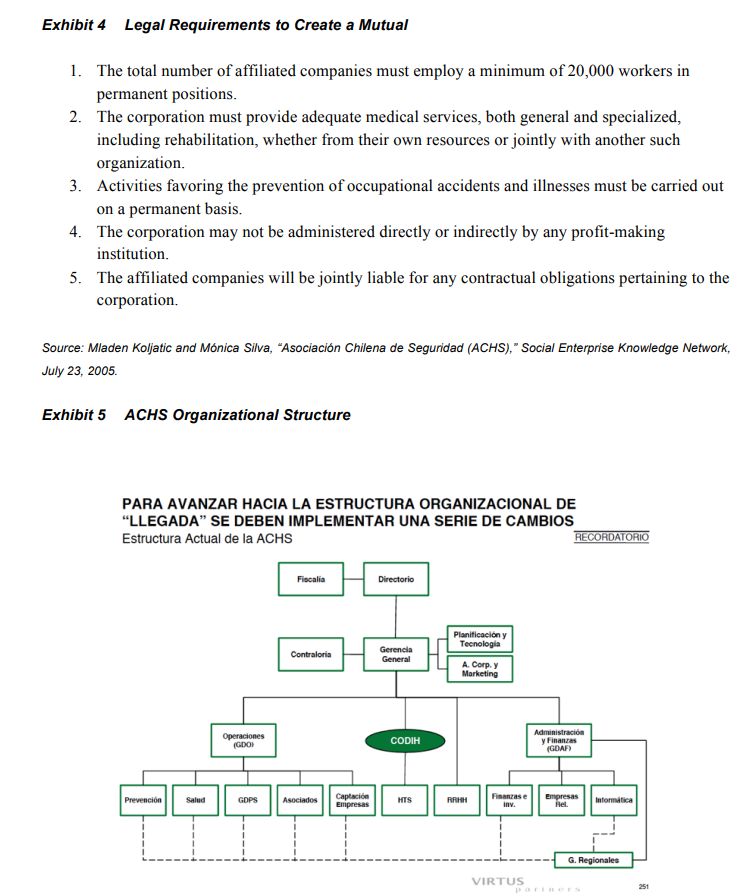

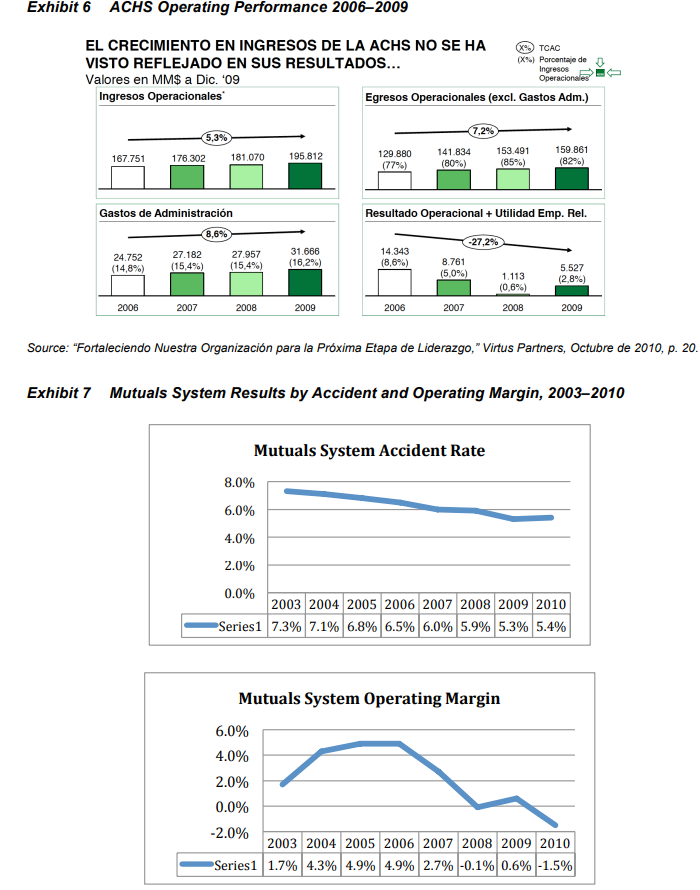

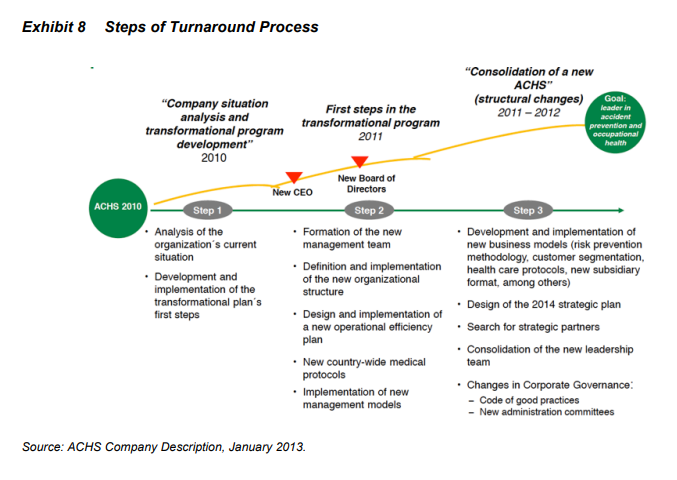

Asociacin Chilena de Seguridad (ACHS) (A): Honoring a Legacy, Embracing Change Leigh Hafrey and Cate Reavis We knew that the change needed at ACHS would require more than bringing in a new manager or two. We were looking to change the culture and introduce a new value system. - Fernn Gazmuri, President, ACHS Board of Directors In mid-2010, things were not looking good for Asociacin Chilena de Seguridad (ACHS), a workers' insurance non-profit corporation. 1 Also known as a "mutual," ACHS provided member companies with risk prevention services and their workers with free, high-quality healthcare and, when needed, salary compensation for work-related accidents and illnesses. ACHS's accident rates 2 were now rising, even as its financial performance declined. In fact, the 52-year-old organization was losing money for the first time. Workers wanted a better healthcare experience, and companies wanted better risk prevention services. Meanwhile, as ACHS coped with its eroding performance, Chile's new probusiness, results-oriented president, Sebastin Piera, was openly communicating his goal of creating a "First World Chile" by 2020.3 ACHS was founded in 1958 by Sociedad de Fomento Fabril (SOFOFA), a federation of private industrial companies led by some of the best-known businesspeople in Chile. These included the new company's CEO, Eugenio Heiremans. During the half-century that followed the founding of ACHS, Heiremans focused on enhancing the dignity of the Chilean worker by improving safety and health conditions; he believed in putting the well-being of people ahead of all else. 4 Now 87 years of age and suffering from a debilitating illness, Heiremans knew it was time to step down. SOFOFA's Executive Committee asked committee member Fernn Gazmuri, ACHS's newest board member, to set the change process in motion. Finding the right successor for Heiremans would require a better understanding of how ACHS operated and a leader who could reverse the organization's decline in performance while maintaining its historical commitment to the safety and health of the Chilean worker. Chile Theories abound about the origin of the name "Chile." One claims that the name came from the Mapuche 5 word chili, which meant "where the land ends." Chile spans nearly 4,000 miles of the south Pacific coastline and a mere 110 miles from the coast to its eastern borders with Bolivia and Argentina. It shares a 104-mile border with Peru to the north, and in the south ends at Cape Horn, 500 miles north of Antarctica. (See Exhibit 1 for map of South America.) With a population of 17 million, Chile is considered one of the most racially homogeneous nations in Latin America. When asked in a 2011 Latinobarmetro survey what race they considered themselves, 59% of Chileans answered "white," 25\% said "mestizo," and 8\% self-classified as "indigenous." Chile is a highly urbanized nation: 90% of the population live in cities, and nearly 40% of that total live in the country's capital city of Santiago. With an average lifespan of 79 years, approximately 43% of Chile's population is between the ages of 25 and 54,7 making it the fastest-aging society in Latin America. By 2030, experts predict, 23% of the population will be in their 60 s and older. 8 Chile's economy depends heavily on mining. The country produces one-third of the world's copper, exports of which account for 20% of GDP and 60% of all exports. 9 Chile has the highest GDP per capita (ppp) in Latin America (Exhibit 2). Augusto Pinochet and the "Chicago Boys" Many credit Chile's strong economic position to the policies put in place during the days of its military government under Gen. and then President Augusto Pinochet. Named Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army by President Salvador Allende in 1973, Pinochet led a successful, U.S.-backed coup against Allende, who was three years into creating a "classless state without private property." 10 Allende had told a New York Times reporter shortly after he was elected president in 1970 that "Man is freed when he has an economic position that guarantees him work, food, housing, health, rest, and recreation.... I think Socialism frees man." "11 By the time of his overthrow, skyrocketing inflation rates, a contraction in industrial output, a thriving black market, a fiscal deficit that was growing due to uncollected taxes, and shrinking foreign-exchange reserves gripped Chile. 12 After taking power, Pinochet called on a group of Chileans who had been educated at the University of Chicago under the Nobel Prize-winning, neoliberal economist Milton Friedman to help him save the Chilean economy. This group of economists came to be known as the "Chicago Boys." Their freemarket, minimal-state intervention economic philosophies led to curtailing state participation in the economy. They encouraged export growth, removed trade barriers, and privatized social security and state companies. 13 Labor unions, which under Allende had been actively involved in Chilean politics and permitted to engage in collective bargaining both at the enterprise and industry levels, saw their influence severely limited. The 1979 Labor Plan outlawed union confederations, allowed collective bargaining only at the company level, and prohibited unions from requiring members to pay dues. During a strike, a company could impose a lockout, temporarily lay off workers, and hire replacements..14 From 1986 to 1997 , the Chilean economy grew on average 7.5% annually. 15 Friedman, who noted how remarkable it was that Chile's military junta "adopted the free market arrangements instead of the military arrangements," ,6 soon dubbed it the "Chilean Miracle." In addition to his economic plan, Pinochet engaged in political and social reforms, one consequence of which was the killing or disappearance of over 3,000 political opponents and the torture of tens of thousands. 17 Inequality High unemployment and increasing levels of poverty and income inequality led to Pinochet being voted out of office in 1990. Friedman noted that Pinochet's ouster was an indirect result of the free market policies that governed Chile during the 1970s and 1980s. As he reflected some years later, "The Chilean economy did very well, but more important, in the end the central government, the military junta, was replaced by a democratic society. So the really important thing about the Chilean business is that free markets did work their way in bringing about a free society." 18 The center-left coalition governments known as Concertacin, which led Chile from 1990 to 2010 , increased social spending as a way to tackle the country's level of poverty. The poverty rate fell from 45% in the mid-1980s to 15% by the mid-2000s. 19 In concert with improved levels of poverty, the university student population soared from 200,000 in 1990 to 1.1 million in 2010.20 The country's GDP continued to grow, albeit not quite at the levels it had under the last years of Pinochet (Exhibit 3). Chile's economic growth and social and political stability were recognized with its acceptance into the OECD in 2010, making it the first South American country to be admitted. However, as one academic pointed out, "Only a minor sector of society benefitted from [Chile's] productivity growth." 21 Inequality, brought on by the free market policies put in place under Pinochet, remained a glaring problem with the vast majority of Chileans not represented in its growth figures. Chile had the most uneven distribution of wealth in the OECD. According to the World Bank, between 2005 and 2009 , the highest 20% of income earners accounted for 57% of total income and the lowest 20% just 4.5%. As one researcher found, 20% of Chileans had incomes equal to those of a developed country while the rest had incomes of a middle- or low-income country. Another researcher noted that nine out of ten workers in Chile made less than the average minimum salary in developed countries. 22 The country's social and economic inequality manifested itself in the healthcare system. Approximately, 72% of the population belonged to FONASA, the government-run health insurance plan that required members to contribute 7% of their income for coverage. However, roughly 40% of FONASA beneficiaries qualified as poor or destitute and did not pay the 7\% contribution or a copay at time of service. 23 Isapres, private health insurance companies, covered 17% of Chileans, typically those with higher incomes who were considered a low health risk. Forty-five percent of Isapres beneficiaries were in the top 20% income bracket. 24 However, as they aged and their healthcare needs became more complex and expensive, many Chileans left Isapres and joined FONASA. 25 Mutuals Chile's tradition of "mutuals" and the law that governed them began with ACHS in 1958. With an industrial accident happening every 27 seconds, 26 the business leaders of SOFOFA set out to lower Chile's accident rate by developing risk prevention programs and providing workers with healthcare coverage and compensation for job-related accidents and illnesses. They envisioned an insurance network that was "universal and based on a system of mutual support," void of discrimination based on a company's size or level of risk. 27 In 1968, when the accident rate in Chile was more than 35%, the Chilean government, led by President Eduardo Frei Montalva from the Christian Democratic Party, passed a law (16.744) requiring all companies to join either the government worker insurance provider or one of Chile's three private mutuals: ACHS; IST, founded in the same year as ACHS, which served companies and their workers in the Aconcagua and Valparaso regions, north of Santiago; or, MSCCC, founded in 1966 to serve the construction industry. Up until that time, membership in a mutual had been optional. The 1968 law required mutuals to provide members: 1. Risk prevention services to prevent work accidents and occupational illnesses. Together with member companies, the mutuals developed plans to avoid and reduce accidents and occupational illnesses. 2. Healthcare services to treat work-related accidents and illnesses. This included physical and occupational therapy. 3. Financial compensation and pension management during the time a worker took temporary leave due to an accident or illness or retirement due to a permanent disability. In return for risk prevention, healthcare, and financial services, member companies paid mutuals a flat rate of 0.95% of all salaries as well as an additional 03.4% of a worker's salary (the combined fixed and variable rate average was 1.6% ) according to the level of risk associated with the industry and the safety record of each company. This dues model incentivized companies to address their work-related accidents and illnesses in order to bring down their rates; paradoxically, it then put downward pressure on the mutuals' earning potential. 28 Throughout their history, the three private mutuals had operated without significant competitive threats. While new mutuals were permitted to enter the sector, the legal requirements were fairly restrictive (Exhibit 4). Since the 1968 law set the member rates, mutuals could only differentiate themselves on their ability to lower accident rates, which would lower the rates companies were required to pay. 29 The mutual system experienced significant growth as Chile's economy grew. As more companies were started in Chile beginning in the late 1980s and into the 1990s and 2000s-between 2007 and grew. More workers and higher salares led to greater income for mutuals. Given their socially conscious focus, many wondered how the non-profit mutuals survived during the Pinochet/"Chicago Boys" era. Heiremans, who knew Pinochet and had been close to his military government, offered an explanation: When the military government took over in 1973, the success of mutuales was already widely recognized, and they were held in high esteem by the society in general. However, the team that determined the economic policies of that time adhered dogmatically to the belief that everything should be based on profit.... However, in the case of ACHS and the other mutuales, a profitseeking orientation would be counterproductive because market pressures would lead to the selection of 'good' clients only [or] those with low accident risks. Who would want to take on the high accident risks? In the end, the state would have to provide coverage for those cases, and we all know the low quality of health services that the state manages to offer.... 31 ACHS With roughly 4,000 employees, ACHS and its country-wide network of 100 agencies provided risk prevention services to 38,000 companies, 84% of which had 50 or fewer employees (7.6% had 50 100,6.9% had 101-500, 1.5% had 500+ ), and delivered healthcare and financial services to two million workers. (See Figure 1 for a breakdown in ACHS industry membership by company and worker and by industry accident rates.) Among the three private mutuals, ACHS was the market share leader with 52%; MSCCC and IST had 34% and 14%, respectively. 32 Figure 1 ACHS Members by Industry 2010 Source: "Memoria Anual 2010," ACHS, p. 66 (http://www.achs.cl/portal/ACHS-Corporativo/Documents/memoria-2010.pdf, accessed July 9, 2015). As ACHS's founder, Heiremans had built a non-profit corporation that took great pride in its work and in the treatment of its people. Employees were paid well and given generous healthcare benefits. (They could receive healthcare at lower rates at ACHS's healthcare facilities.) They were also guaranteed a financially stable retirement if they stayed with the company. Employees contributed 2% of their monthly salary to a retirement fund, an amount matched by ACHS. Upon retirement, they received 100% of their most recent monthly salary times the number of years employed. Employees averaged 19 years on the job, and the executive team 29 years. In 2009, ACHS scored 31st on the Best Places to Work in Chile rankings. 33 Organizational Structure As executive president of ACHS, Heiremans led the organization's six-person board of directors, which included three directors representing member companies and three directors representing workers. A director could serve an unlimited number of three-year terms. The board met monthly: each member had one vote; in case of a tie, Heiremans had an additional vote. Heiremans's influence extended well beyond the boardroom. He kept an office at ACHS, which he visited every day. It was well known that he made almost all the business decisions at ACHS, a leadership model that made sense to many of the company's executives. As one commented: "When the ship has only one captain, it's easy to make decisions. In the middle of a storm, you can't have a meeting and democratically decide whether to go to port or starboard, because the ship would sink in the meantime." "34 On paper, ACHS's CEO (GG on the organizational chart), to whom the directors of operations and finance and administration reported, led the management team and reported to the board. (See Exhibit 5 for the ACHS Organizational Chart.) The heads of ACHS's risk prevention and healthcare services reported to the director of operations; the organization's 15 regional managers, who were responsible for overseeing the geographically dispersed agencies that provided risk prevention, healthcare, and financial services, reported to the head of finance and administration. Each regional manager had been handpicked by Heiremans and had considerable power. They were given autonomy to run their areas as they wished, deciding on which organizational structures and job titles made the most sense to them. Risk Prevention and Safety and Healthcare In accordance with the law, ACHS had two lines of business: risk prevention and safety and healthcare. Risk Prevention and Safety ACHS was originally founded to provide risk prevention and safety services to companies throughout Chile in order to bring down the nation's accident rate. The organization helped its member companies avoid accidents by providing training programs to introduce environmental and health safety (EHS) competencies. These included hygiene programs to prevent occupational illnesses; fire and biohazard agent training; and psychosocial programs to develop and sustain a culture of safety. ACHS's work in risk prevention and safety extended to the community at large with campaigns that addressed how to avoid day-to-day public transportation accidents, prevent swimming pool accidents, and educate children about the importance of EHS at home. Roughly 17% of ACHS employees worked in risk prevention and safety, which accounted for 15% of the organization's operating costs. 35 Healthcare ACHS ran 97 primary healthcare centers throughout the country and a trauma hospital in Santiago. The organization also co-owned 12 regional clinics with its competitor MSCCC, resulting from a 2005 alliance when excess capacity led the organizations to merge some of their locations. 36 ACHS co-owned an additional seven clinics with other partners. The ACHS medical team included 373 doctors with different specialties, including 135 in orthopedics, and a team of health professionals dedicated to rehabilitation and workplace reentry. On average, ACHS provided care for 250,000 workers annually with an average treatment rate of 7.9 days, up from 7.7 days in 2008 . Roughly 95% of the workers received treatment locally through the organization's primary healthcare centers, and 5% had to be treated in clinics or hospitals. Healthcare accounted for 55% of ACHS's employees and 45% of operating costs. 37 (Financial compensation for workers who became sick or were injured on the job represented 27% of operating costs. 38 ) ACHS also owned a 2,000-person transportation and first aid administrator company (ESACHS) that owned 500 ambulances and other emergency vehicles and that transported up to 70,000 people a month to hospitals and clinics. The first-aid side of ESACHS provided first aid to workers, particularly those located in hard-to-reach areas. Many of the 100 first-aid facilities within member organizations and companies throughout Chile had a doctor on staff. Depending on their in-house first-aid needs, some companies, such as those wanting a doctor on staff, paid ACHS an additional fee. Other Stakeholders Aside from its own employees, ACHS's key stakeholders included affiliated companies, workers at affiliated companies and their unions, and the government. For affiliated companies, ACHS's value proposition was the degree to which it helped curtail work-related accidents and illnesses, thereby lowering the variable fee that affiliates paid to ACHS. For many years, affiliated companies had voiced dissatisfaction with the organization's risk prevention and safety services, and believed that the organization had focused too much on healthcare. Workers, and the unions that represented them, looked to ACHS for the free healthcare provided when a work-related accident or illness occurred and for financial compensation services when they were unable to work. While workers were satisfied with the healthcare they received, especially when compared to the quality provided by public healthcare clinics, they complained about the amount of time they had to wait to see a doctor. The government's demands on ACHS shifted depending on which political party or coalition led the government. For example, President Michelle Bachelet was an outspoken defender of workers' rights during her time in office from 2006 to 2010. During her term, ACHS focused more on the workers' experience by continuing to improve the quality of healthcare they received. Pro-business president Piera, elected after Bachelet, stressed the importance of liberal, open, competitive markets to keep Chile on its development trajectory. He questioned the ability of a group of non-profits to lead the workers' insurance industry and sought a for-profit competitor to shake up the industry landscape. Time for Change The year 2010 marked the first year ever that ACHS had run an operational deficit. 39 For several years, the organization's operating expenses had been growing faster than its operating income. Between 2006 and 2009, operating income grew 5.3% while operating expenses (excluding administrative costs) grew 7.2%. Administrative costs were up 8.6% over the same time period. Operating results had tumbled 27.2\% (Exhibit 6). Meanwhile, the organization's retirement fund faced a $40 million liability. However, ACHS's stakeholders were arguably more concerned with its apparent struggle, along with the entire mutual system, to lower the nation's accident rate (Exhibit 7). 40 As one manager explained it, ACHS could no longer lower its rate by its previous means-implementing rules and regulations, providing procedures, and hoping that employees complied. Member companies voiced their dissatisfaction with ACHS's risk prevention efforts, and many of the larger ones handled risk prevention and safety in-house. SOFOFA's executive community had chosen Fernn Gazmuri to take the lead in determining how to turn around ACHS. Gazmuri was the president of Citron Chile, a substitute board member at ACHS since 2002 , and a permanent member beginning in 2010 . He began by carefully broaching the subject of a successor with Heiremans. Gazmuri also proposed that ACHS hire an outside consulting company to assess what the organization did well and not so well, and to determine the depth and breadth of change needed. While Gazmuri knew that neither of these conversations would be easy, he believed that Heiremans would have to bless any change initiative for it to succeed, and do so publicly. Fortunately, Heiremans offered no resistance, and ACHS's other board members also agreed with Gazmuri's recommendations, though they never did so in front of Heiremans. (The two other board directors representing member companies had each been on the ACHS board for more than 20 years and had close personal relationships with Heiremans.) Heiremans relinquished his CEO position in June 2010, and resigned from the board in October 2010. He died two months later, but by then ACHS employees knew that he had approved the need for new leadership and the assistance of outside consultants. During his final months, Heiremans did not participate in discussions on the type of leader ACHS should seek, but he did share with Gazmuri his concern that the inevitable dismissal of some employees would disrupt ACHS's paternalistic and fraternal culture. He recommended that the changes be made slowly, in order to reduce the negative impact they would have on the organization. Virtus and Its Assessment The ACHS board hired Virtus Partners (Virtus), a Chilean consulting firm founded by two former McKinsey partners, to help lead the turnaround. Virtus launched its assessment of the organization in July 2010, just one month before a mining accident trapped 33 Chilean copper miners 2,000 feet below ground for 69 days. The company that owned the mine was a member of ACHS. Virtus carried out interviews and focus groups with ACHS employees - many of whom referred to the consulting company as "virus" - and with its stakeholders, and also conducted a deep analysis of financials and other operational data, as well as an inventory of systems and processes. As one Virtus consultant explained, "We found a company lacking any governance.... It was unchallenged and slow. There was no innovation." In addition, many employees didn't seem to understand what it meant to be a non-profit: some read ACHS's non-profit status as meaning that the company didn't need to worry too much about costs; it needed to earn money and spend it. Structure Even before Virtus began its assessment process, it was clear that ACHS operated with a highly centralized structure at the top but with a decentralized structure among the healthcare and risk prevention businesses and among the different regions. As executive president for over 50 years, Heiremans had made all major operating and businessrelated decisions. More often than not, he reported to the board after those decisions had already been made. Virtus found little communication between the healthcare and risk prevention businesses. The area heads competed for power, resources, and larger teams. In addition, they were both jockeying to be the next Heiremans. The regions also communicated very little with headquarters, and did not share a vision of what ACHS should be and how it should operate. One Virtus consultant noted that ACHS consisted of 15 different companies, a structure that had made sense in the days before Chilean companies operated in multiple locations, because it allowed ACHS to be physically close to its members. However, that structure no longer applied. Human Capital Many of ACHS's employees had spent their entire careers with the company and had never been exposed to other ways of managing or working in a business setting. The average age of the 30 most senior managers was 60 , and their average length of service was 29 years. 41 People stayed in the same position for many years; personnel rotation was uncommon. There was considerable administrative fat, with central administration accounting for 12% of operating costs, slightly lower than risk prevention's 15%.42 Headquarters had 700 employees, of whom 120 were administrative assistants. (Some managers had three personal assistants.) Virtus discovered that a good number of employees had come to ACHS because of family connections. "Many decisions were based on if you were someone's friend or relative," explained a Virtus consultant. "It was not a meritocracy." Nearly all employees received good or excellent ratings on their annual performance evaluations-making it impossible to tell who was and wasn't pulling their weight - and 20% of the organization's bottom line was divided equally among all employees for annual bonuses. In general, Virtus found a workforce lacking promotable talent. For the most part, employees didn't try to figure out ways to do their jobs better. They aimed to maintain the status quo. Employees who filled out workplace surveys for Virtus rated employment security as the feature they most valued at ACHS. The organization had never dismissed anyone, and people left the office every day promptly at closing even if they had not solved a member's problem. Operations ACHS's decentralized structure resulted in a lack of operational consistency; few enforced administrative processes; there was little accountability and little emphasis on or concern about results. Virtus discovered that ACHS's various agencies could set their own budgets and decide how to spend money. They chose their organizational structure, job titles, hours of operation, and suppliers. Safety and risk prevention was taught differently from one ACHS agency to another, and doctors at ACHS's health centers did not follow a single medical protocol. A doctor at one health center, for example, might give a worker with a sprained ankle five days lost work time, while a doctor at another facility might give the same injury 10 days. Doctors felt little internal pressure to ensure that workers returned to work as soon as possible; rather, they aimed to give the best medical care possible. At the same time, workers who were paid while on medical leave did not have much incentive to return to work as soon as possible; yet lost work time cost both ACHS and the member company money. ACHS had no IT system to connect all the agencies, regions, and headquarters. Basic reports pertaining to operations or customer service took two or three weeks to create, because the company's legacy systems did not talk to one another. ACHS spent up to $15 million a year in technology patches and short-term fixes. Goals 1. Get closer to customers in both business segments. On the healthcare side, "customers" meant the workers; on the risk prevention side, it referred to the appropriate leaders and managers at member companies. 2. Build a high-performance management team and board of directors. 3. Develop an efficient operation in order to bring down operational costs. This included centralizing and standardizing certain processes and installing new technology systems. 4. Create a results-oriented culture, with specific performance targets and measurement systems. (See Exhibit 8 for timeline of turnaround.) The Next Heiremans? While Virtus delved into the inner workings of ACHS, Gazmuri began conversations with the board about the type of leader ACHS needed to succeed Heiremans. One profile that emerged was of an early-to-mid-career professional experienced in enacting change. Such a person would bring in new talent, implement modern management tools and systems, and make the change process happen fast. As with any organization experiencing performance erosion, everyone wanted the most rapid turnaround possible. Yet speed had its risks, particularly in an organization that had been led by the same person since its founding. How would that urgency affect ACHS's ability to serve its member companies and their workers? Would it be too disruptive? Would ACHS employees rebel, feeling that such a leader didn't respect Heiremans and his legacy? What about the board? After following Heiremans for so long, would they back a new leader moving the organization in a new direction? Heiremans had stressed the dignity and well-being of the Chilean people above all else. Now the political and economic context in which Gazmuri and others hoped to turn around ACHS had the potential to generate serious tension with that goal. On the one hand, Chile's recent admission into the OECD made the country's sharp disparities in income and wealth all the more evident. Under Heiremans, ACHS had provided services that somewhat mitigated those disparities. On the other hand, a struggling ACHS would introduce its new leader shortly after the swearing-in of Chile's first conservative president since Augusto Pinochet. President Piera, a billionaire businessman, was committed to revitalizing an economy beset by 10% unemployment and to attaining "developed" status for Chile by 2020. He sought to do this by cutting red tape for businesses, encouraging investment, and increasing productivity and wages. As Piera put it, "I want to bring back those years of the fat cows, when everybody talked about the Chilean Miracle.,"43 ACHS's new CEO would need to assess the organization's opportunities in this changing business and political environment. Exhib Exhibit 2 Economic and Social Data for Select South American Countries Source: The World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/countries, accessed July 17, 2015); hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/. Exhibit 3 Chile GDP Growth, 1980-2008 Source: The World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/countries, accessed July 17, 2015); hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/. Exhibit 4 Legal Requirements to Create a Mutual 1. The total number of affiliated companies must employ a minimum of 20,000 workers in permanent positions. 2. The corporation must provide adequate medical services, both general and specialized, including rehabilitation, whether from their own resources or jointly with another such organization. 3. Activities favoring the prevention of occupational accidents and illnesses must be carried out on a permanent basis. 4. The corporation may not be administered directly or indirectly by any profit-making institution. 5. The affiliated companies will be jointly liable for any contractual obligations pertaining to the corporation. Source: Mladen Koljatic and Mnica Silva, "Asociacin Chilena de Seguridad (ACHS)," Social Enterprise Knowledge Network, July 23, 2005. Exhibit 5 ACHS Organizational Structure PARA AVANZAR HACIA LA ESTRUCTURA ORGANIZACIONAL DE "LLEGADA" SE DEBEN IMPLEMENTAR UNA SERIE DE CAMBIOS Estructura Actual de la ACHS AECOADATORIO EL CRECIMIENTO EN INGRESOS DE LA ACHS NO SE HA TCAC VISTO REFLEJADO EN SUS RESULTADOS... Porcentaje de 8. Source: "Fortaleciendo Nuestra Organizacin para la Prxima Etapa de Liderazgo," Virtus Partners, Octubre de 2010, p. Exhibit 7 Mutuals System Results by Accident and Operating Margin, 2003-2010 Fyhihit \& Stone of Turnarnund Pronese Source: ACHS Company vescription, January zUT3

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started