Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

What is your forecast free cash flows for the existing machine? The Zinser? What are their respective NPVs? CASE Aurora Textile Company In January 2003,

What is your forecast free cash flows for the existing machine? The Zinser? What are their respective NPVs?

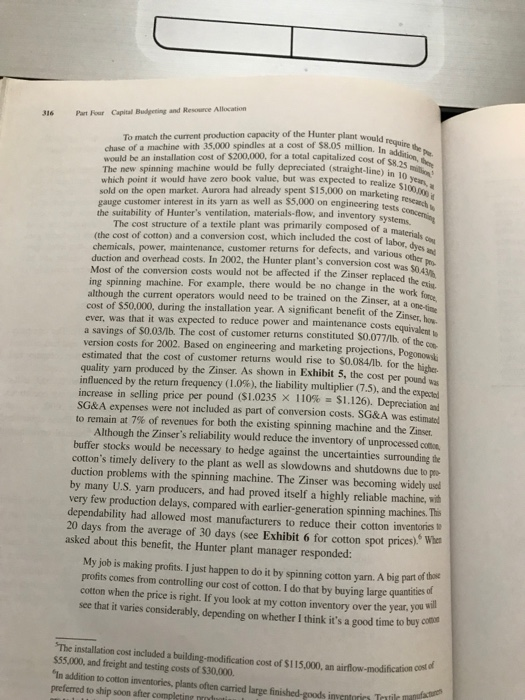

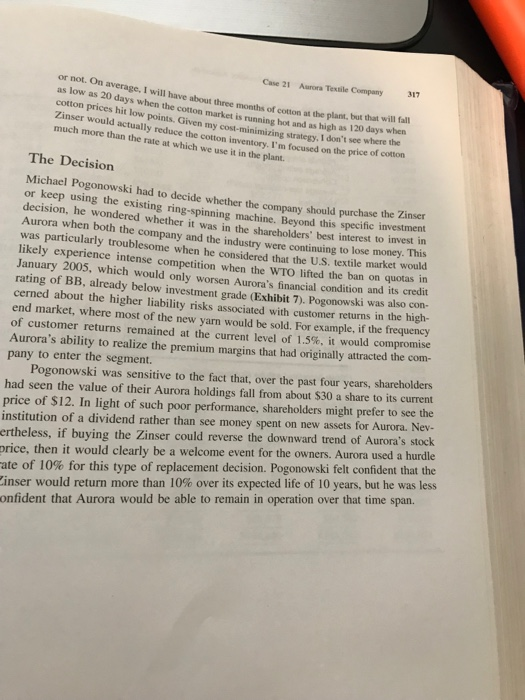

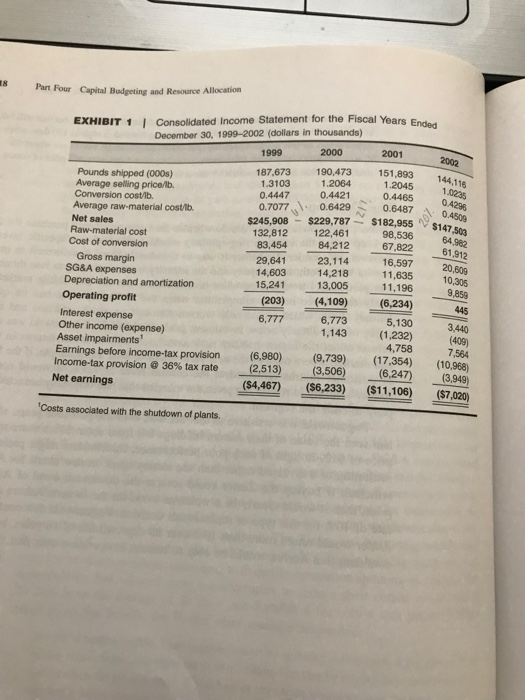

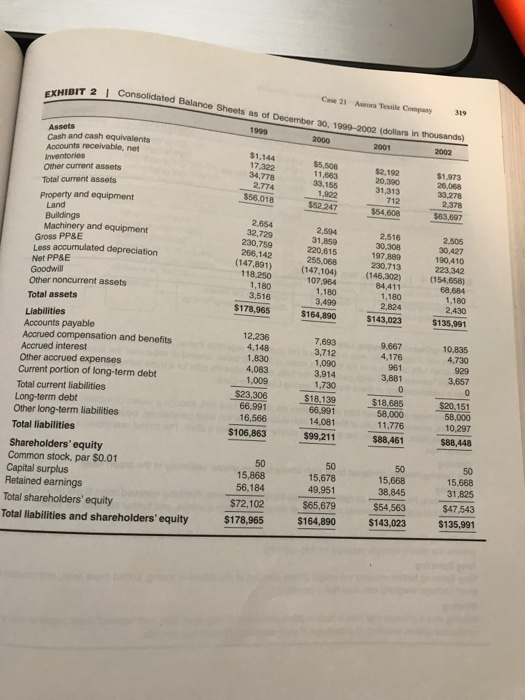

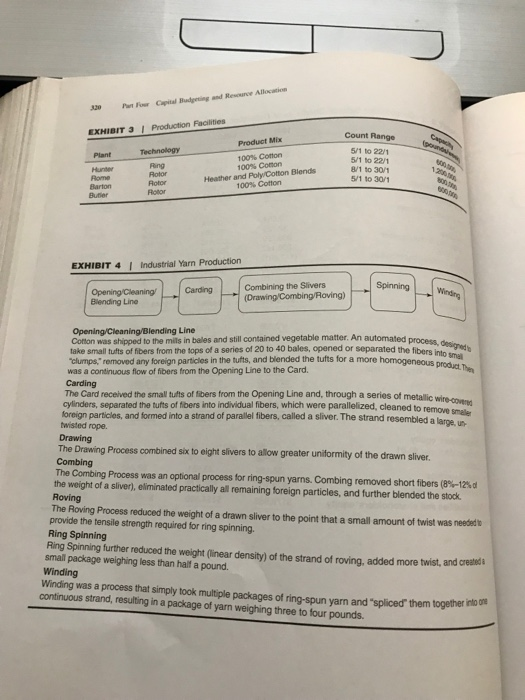

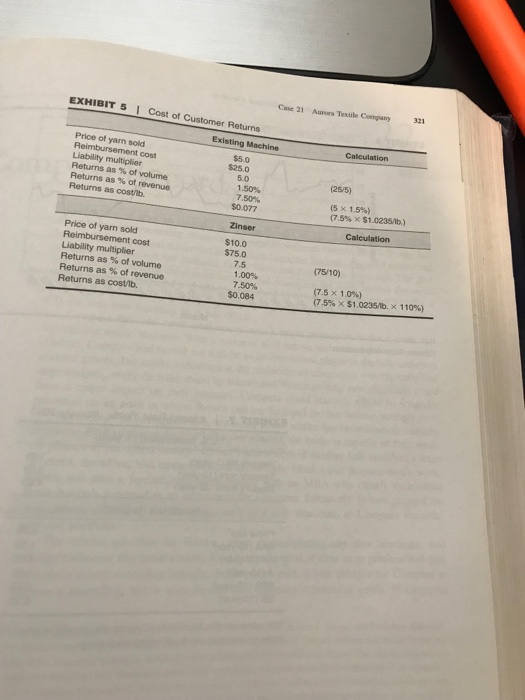

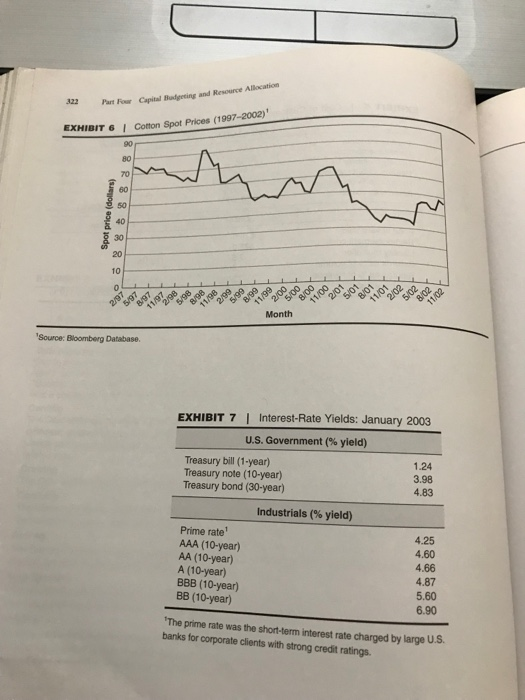

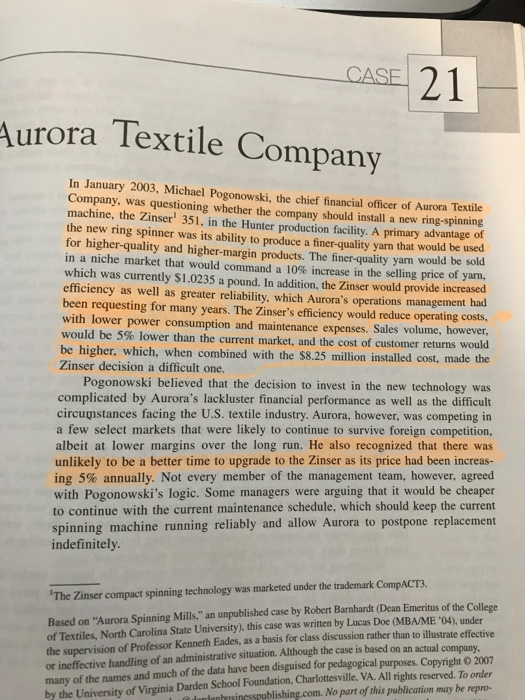

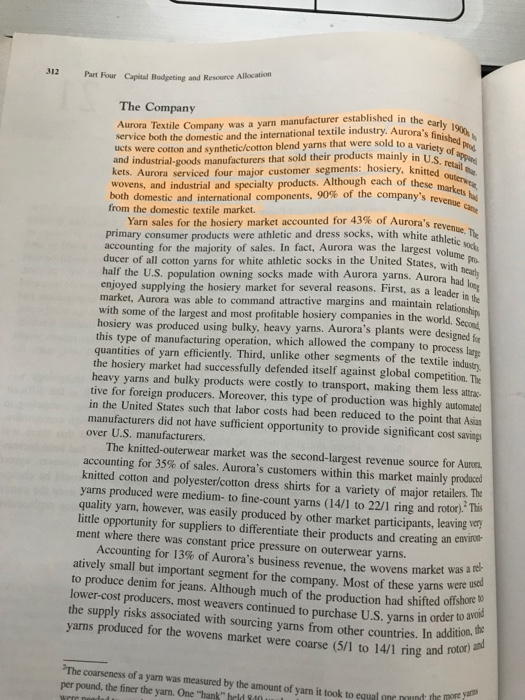

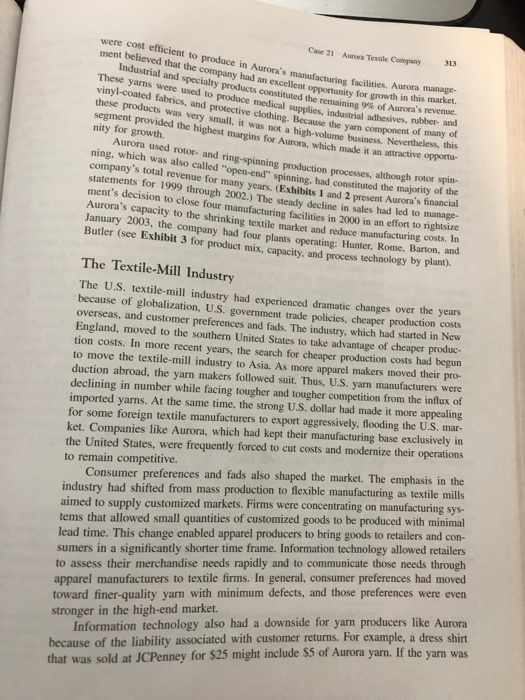

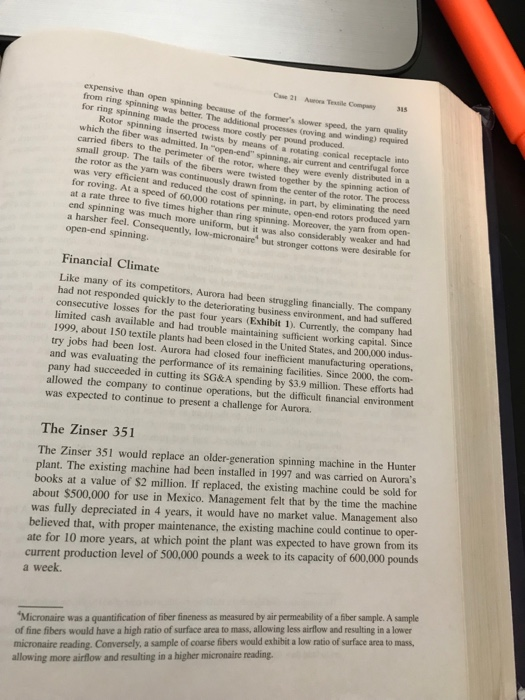

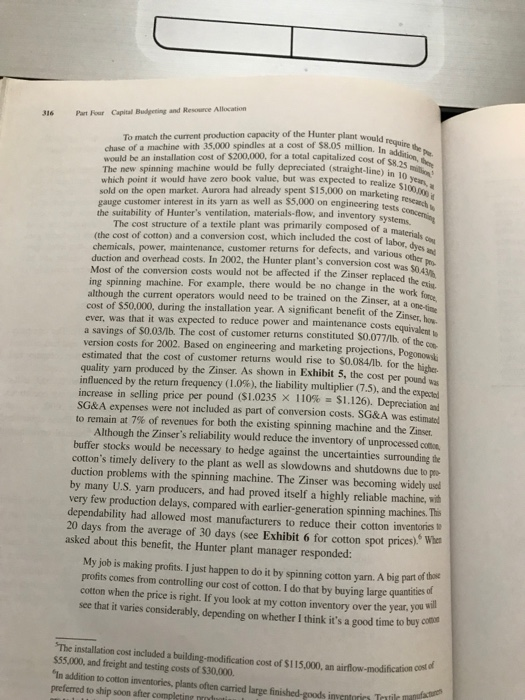

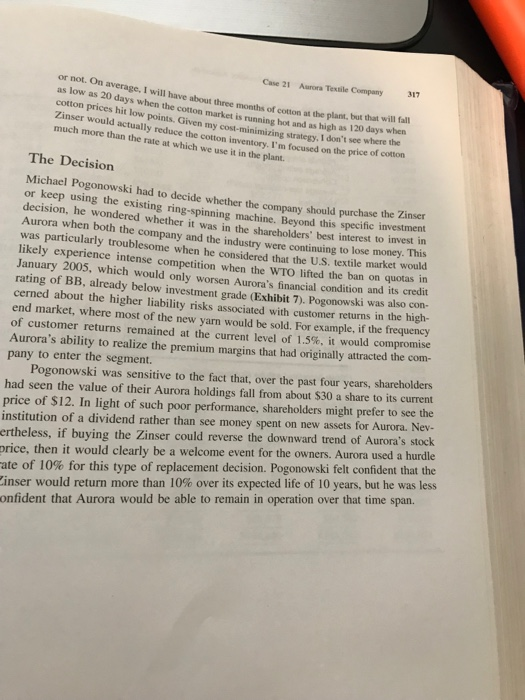

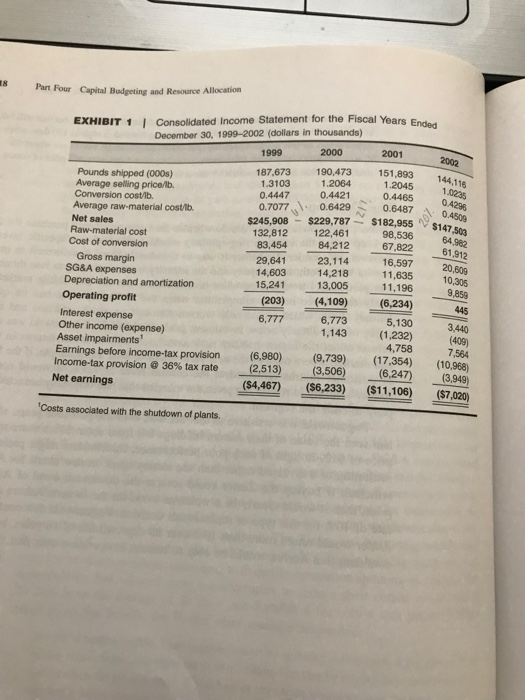

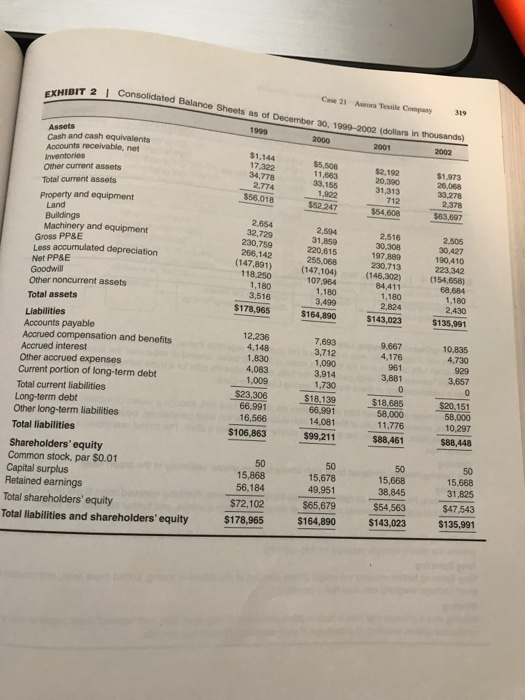

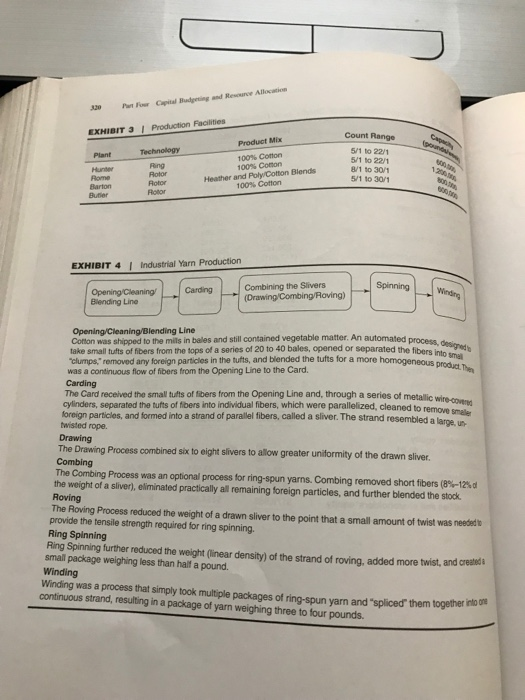

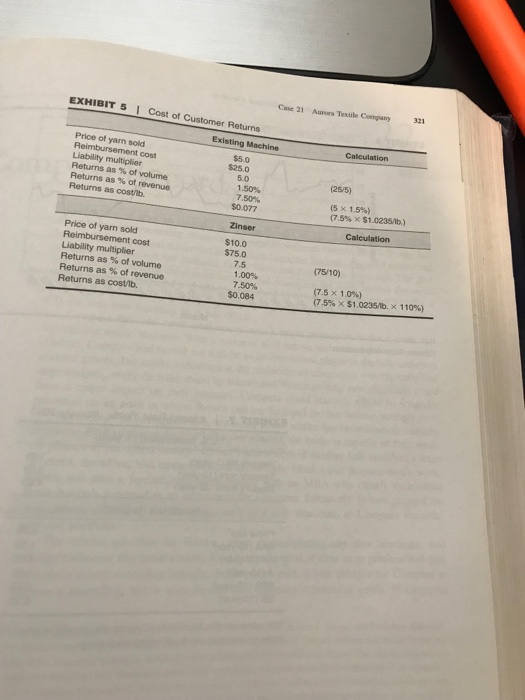

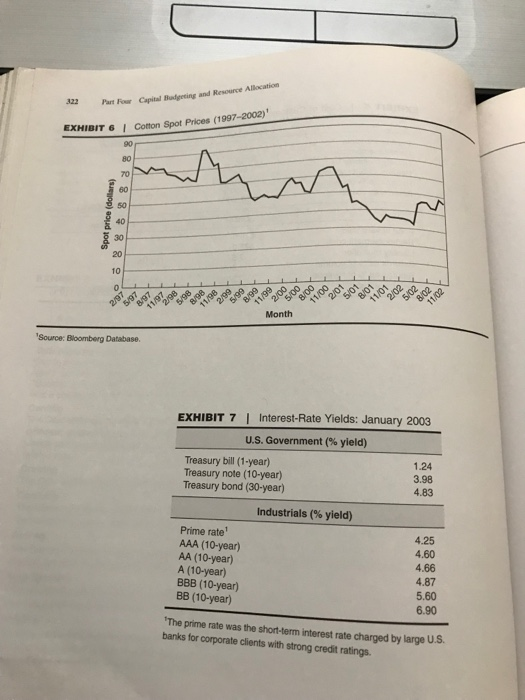

CASE Aurora Textile Company In January 2003, Michael Pogonowski, the ompany, was questioning whether the company should install a new ring-spinning machine, the Zinser 351, in the Hunter production facility. A primary advantage of the new ring spinner was its ability to produce a finer-quality yarn that would be used for higher-quality and higher-margin products. The finer-quality yam would be sold in a niche market that would command a 10% increase in the selling price of yarn, which was currently $1.0235 a pound. In addition, the Zinser would provide increased efficiency as well as greater reliability, which Aurora's operations management had been requesting for many years. The Zinser's efficiency would reduce operating costs, with lower power consumption and maintenance expenses. Sales volume, however would be 5% lower than the current market, and the cost of customer returns would be higher, which, when combined with the $8.25 million installed cost, made the chief financial officer of Aurora Textile Zinser decision a difficult one. Pogonowski believed that the decision to invest in the new technology was complicated by Aurora's lackluster financial performance as well as the difficult circumstances facing the U.S. textile industry. Aurora, however, was competing in a few select markets that were likely to continue to survive foreign competition, albeit at lower margins over the long run. He also recognized that there was unlikely to be a better time to upgrade to the Zinser as its price had been increas- ing 5% annually. Not every member of the management team, however, agreed with Pogonowski's logic. Some managers were arguing that it would be cheaper to continue with the current maintenance schedule, which should keep the current spinning machine running reliably and allow Aurora to postpone replacem indefinitely The Zinser compact spinning technology was marketed under the trademark CompACT3. Based on "Aurora Spinning Mills," an unpublished case by Robert Barnhardt (Dean Emeritus of the College of Textiles, North Carolina State University), this case was written by Lucas Doe (MBA/ME '04), under the supervision of Professor Kenneth Eades, as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Although the case is based on an actual company many of the names and much of the data have been disguised for pedagogical purposes. Copyright 2007 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rghts reserved. To order usinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be repro- 312 Part Four Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocation Aurora Textile Company was a yarn manufacturer established in the o service both the domestic and the international textile industry. Aurora's f The Company early 1900 ucts were cotton and synthetic/cotton blend yarns that were sold toP and industrial-goods manufacturers that sold their products mainly in U.S, wovens, and industrial and specialty products. Although each of these both domestic and international components, 90% of the company's reve from the domestic textile market. markets enue canie revenue volume primary consumer products were athletic and dress socks, with white ath accounting for the majority of sales. In fact, Aurora was the largest vl soc ducer of all cotton yarns for white athletic socks in the United States, with Yarn sales for the hosiery market accounted for 43% of Aurora's half the U.S. population owning socks made with Aurora yarns. Auroa enjoyed supplying the hosiery market for several reasons. First, as a l market, Aurora was able to command attractive margins and maintain re in the with some of the largest and most profitable hosiery companies in the world. Secm hosiery was produced using bulky, heavy yarns. Aurora's plants were designed for this type of manufacturing operation, which allowed the company to process lage quantities of yarn efficiently. Third, unlike other segments of the textile industry the hosiery market had successfully defended itself against global competition. The heavy yarns and bulky products were costly to transport, making them less attrac tive for foreign producers. Moreover, this type of production was highly automated in the United States such that labor costs had been reduced to the point that Asian manufacturers did not have sufficient opportunity to provide significant cost savings over U.S. manufacturers. The knitted-outerwear market was the second-largest revenue source for Aure accounting for 35% of sales. Aurora's customers within this market mainly produced knitted cotton and polyester/cotton dress shirts for a variety of major retailers. The yarns produced were medium- to fine-count yarns (14/1 to 22/1 ring and rotor). Tis quality yarn, however, was easily produced by other market participants, leaving ver little opportunity for suppliers to differentiate their products and creating an envine ment where there was constant price pressure on outerwear yarns. atively small but important segment for the company. Most of these yarns lower-cost producers, most weavers continued to purchase U.S. yarns in Accounting for 13% of Aurora's business revenue, the wovens market was a red used to produce denim for jeans. Although much of the production had shifted ofshoc- order to avoid addition, the the supply risks associated with sourcing yarns from other countries. In yans produced for the wovens market were coarse (5/1 to 14/1 ring and roton The coarseness of a yarn was measured by the amount of yarn it took to equal 0 per pound, the finer the yarn. One "hank hrld 810 Case 21 Aurora Texile Company 313 were cost efficient to produce in Aurora's manufacturing facilties this market. ment believed that the company had an excellent opportunity for grow Industrial and specialty products constituted the remaining 9% These yarns were used to produce medical vinyl-coated fabrics, and protective clothing. Because the yarn comp these products was very small, it segment provided the highest margins for Aurora, wlich made nity for growth. facilities. Aurora manage- th in this market. of Aurora's revenue. supplies, industrial adhesives, rubber- and nent of many of was not a high-volume business. Nevertheless, this Aurora used rotor- and ring-spinning production processes, although rotor spin- was also called "open-end" spinning, had constituted the majority of the enue for many years. (Exhibits 1 and 2 present Aurora's financial ning, tatements for 1999 through 2002.) The steady decline in sales had led to manage- ment's decision to close four manufacturing facilities in 2000 in an effort to rightsize Aurora's capacity to the shrinking textile market and reduce manufacturing costs. In January 2003, the company had four plants operating: Hunter, Rome, Barton, and Butler (see Exhibit 3 for product mix, capacity, and process technology by plant). The Textile-Mill Industry The U.S. textile-mill industry had experienced dramatic changes over the years because of globalization, U.S. government trade policies, cheaper production costs overseas, and customer preferences and fads. The industry, which had started in New England, moved to the southern United States to take advantage of cheaper produc tion costs. In more recent years, the search for cheaper production costs had begun to move the textile-mill industry to Asia. As more apparel makers moved their duction abroad, the yarn makers followed suit. Thus, U.S. yarn manufacturers were declining in number while facing tougher and tougher competition from the influx of imported yarns. At the same time, the strong U.S. dollar had made it more appealing for some foreign textile manufacturers to export aggressively, flooding the U.S. mar- ket. Companies like Aurora, which had kept their manufacturing base exclusively in the United States, were frequently forced to cut costs and modernize their operations to remain competitive. Consumer preferences and fads also shaped the market. The emphasis in the industry had shifted from mass production to flexible manufacturing as textile mills aimed to supply customized markets. Firms were concentrating on manufacturing sys- tems that allowed small quantities of customized goods to be produced with minimal lead time. This change enabled apparel producers to bring goods to retailers and con- sumers in a significantly shorter time frame. Information technology allowed retailers to assess their merchandise needs rapidly and to communicate those needs through apparel manufacturers to textile firms. In general, consumer preferences had moved toward finer-quality yarn with minimum defects, and those preferences were even stronger in the high-end market. Information technology also had a downside for yarn producers like Aurora because of the liability associated with customer returns, For that was sold at JCPenney for $25 might include $5 of Aurora yarn. If the yarn was example, a dress shirt 314 Part For Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocatio required to reimburse JCPenney for the full retail price of $25, five tsuld of revenue received by Aurora for the garment. In 2002, 1.5% of the Hanean- volume had been returned by its retailers. The percentage of volume Pla defective and the defect could be traced back to Aurora, the 1.5% of the Hunter and infor ier to identify the yarn man had risen mation flow through the supply chain that made it easier to identi facturer associated with a particular garment. If Aurora began selling yarns for sen over the past few years owing to advancements in technolog the high-end market, the company's dollar liability per garment wouldnae example, if Aurora supplied the yarn for a shirt that sold for $75 at Nordstrom the fact Aurora's tomer return would make Aurora liable for paying $75 to Nordstrom despite th that Aurora would have received only $10 for the yarn used to make the shirt. production engineers were confident that the Zinser would yield such hi yarn that the volume returned would drop to 1.0%. The U.S. government's free-trade policies were implemented through the Nork (CBI American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Caribbean Basin Initiative (c These trade agreements had created a burden on the U.S. textile industry by encourae ing trade with Canada, Mexico, and Caribbean countries, which lowered the prics consumer goods in the U.S. market. This enriched trade also forced U.S. textile com panies to compete against cheaper labor, lower environmental standards, and subsidized operations. The net effect was substantially lower-priced goods for U consumers but a very difficult competitive environment for U.S.-based manufacturers For other parts of the world, the U.S. State Department had used textile and tarifs as a political bargaining tool to obtain cooperation from foreign govens ments. The United States and other countries also used quotas and tariffs as a mech protect the anism to prevent the dumping of foreign goods into local markets and to domestic industry. Recently, however, the World Trade Organization (WTO) had announced that, as the governing body for international trade, it would ban its mem- bers from using quotas, effective January 1, 2005. This move would further open the U.S. market to competition from countries beyond its immediate borders. Notwith- standing this outlook, most research analysts believed that the U.S. textile industry would grow around 2% in real terms, with prices and costs increasing at a 1% inde tion rate for the foreseeable future. Production Technology The production of yarn involved the processes of cleaning and blending. carding combining the slivers, spinning, and winding (Exhibit 4). Aurora used only rotor spinning and ring spinning in its yam production. Ring spinning was a process of inserting rwists by means of a rotating spindle. In ring spinning, twisting the yam and winding it on bobbin occurred simultaneously and continuously. Although ring spinning was mre Established through agreements and negotiations signed by the bulk of the members of the General Ape ment on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO replaced GATT in January 1995. The WTO was an ii tional, multilateral organization that laid down rules for glohal trading expensive than open spinning because of the forme's slower speed he yearn equired from ring spinning was better. The additional processes (roving for ring spinning made the process more costly per pound produced. and winding) required Rotor spinning inserted twists by means of a rotating which the fiber was admitted. In "open-end" spinning, air cdistributed in a carried fibers to the perimeter of the rotor, where they were small group. The tails of the fibers were twisted together by the rotor as the yam was continuously drawn from the trifugal force the spinning action of center of the rotor. The process nating the need was very efficient and reduced the cost of spinning, in part, by elims roduced yarn Moreover, the yarn from open- t and for roving. At a speed of 60.000 rotations per n a rate three to five times higher than ring spinning. minute, open-end rotors end open-end spinning. Financial Climate spinning was much more uniform, but it was also considerably weaker and had Consequently, low-micronaire but stronger cottons were desirable for Like many of its competitors, Aurora had been struggling financially. The company had not responded quickly to the deteriorating business environment, and had suffered consecutive losses for the past four years (Exhibit 1). Currently, the company had limited cash available and had trouble maintaining sufficient working capital. Since 1999, about 150 textile plants had been closed in the United States, and 200,000 indus- try jobs had been lost. Aurora had closed four inefficient manufacturing operations, and was evaluating the performance of its remaining facilities. Since 2000, the com- pany had succeeded in cutting its SG&A spending by $3.9 million. These efforts had allowed the company to continue operations, but the difficult financial environment was expected to continue to present a challenge for Aurona. The Zinser 351 The Zinser 351 would replace an older-generation spinning machine in the Hunter plant. The existing machine had been installed in 1997 and was carried on Aurora's books at a value of $2 million. If replaced, the existing machine could be sold for about $500,000 for use in Mexico. Management felt that by the time the machine believed that, with proper maintenance, the existing machine could continue to oper- ate for 10 more years, at which point the plant was expected to have grown from its was fully depreciated in 4 years, it would have no market value. Management also current production level of 500,000 pounds a week to its capacity of 600,000 pounds a week Micronaire was a quantification of fiber fineness as measured by air permeability of a fiber sample. A sample of fine fibers would have a high ratio of surface area to mass, allowing less airflow and resulting in a lower micronaire reading. Conversely, a sample of coarse fibers would exhibit a low ratio of surface area to mass, allowing more airflow and resulting in a higher micronaire reading. 316 Part oar Capital Budgcing and Resouce Allocation require the p. chase of a machine with 35,000 spindles at a cost of $8.05 mil which point it would have zero book value, but was expected to the suitability of Hunter's ventilation, materials-flow, and inventory s To match the current production capacity of the Hunter plant would In would be an installation cost of $200,000, for a total capitalized cost of sa The new spinning machine would be fully depreciated (straight-line) in realize sold on the open market. Aurora had already spent $15,000 on marketin The cost structure of a textile plant was primarily composed of duction and overhead costs. In 2002, the Hunter plant's conversion cost although the current operators would need to be trained on the Zinser, ata tests systems gauge customer interest in its yarn as well as $5,000 on engineering tests reseach (the cost of cotton) and a conversion cost, which included the cost of labo hls chemicals, power, maintenance, customer returns for defects, and various es labor, dyes and Most of the conversion costs would not be affected if the Zinser replaced the ing spinning machine. For example, there would be no change in the work cost of $50,000, during the installation year. A significant benefit of the Zinset hoe ever, was that it was expected to reduce power and maintenance costs equivalen a savings of $0.03/Tb. The cost of customer returns constituted S0.077/Mb. of the version costs for 2002. Based on engineering and marketing projections, Pogonow estimated that the cost of customer returns would rise to S0.084/lb. for the hiphe. quality yam produced by the Zinser. As shown in Exhibit 5, the cost per pound was influenced by the return frequency ( 10%), the liability multiplier (7.5), and the expect increase in selling price per pound (SI .0235 x 110% $1.126), Depreciation and SG&A expenses were not included as part of conversion costs. SG&A was estimatol to remain at 7% of revenues for both the existing spinning machine and the Zinser. Although the Zinser's reliability would reduce the inventory of unprocessed coton buffer stocks would be necessary to hedge against the uncertainties surrounding the cotton's timely delivery to the plant as well as slowdowns and shutdowns due to pr duction problems with the spinning machine. The Zinser was becoming widely use by many U.S. yarn producers, and had proved itself a highly reliable machine, very few production delays, compared with earlier-generation spinning machines. This dependability had allowed most manufacturers to reduce their cotton inventories w 20 days from the average of 30 days (see Exhibit 6 for cotton spot prices)*Whe asked about this benefit, the Hunter plant manager responded: My job is making profits. I just happen to do it by spinning cotton yarn. A big part of those profits comes from controlling our cost of cotton. I do that by buying large quantifes dr cotton when the price is right.If you look at my cotton inventory over the year, you witn seethat it varies considerably, depending on whether I think it's a good time to buy The installation cost included a building-modification cost of $115,000, an airflow-modification $55,000, and freight and testing costs of $30,000. In addition to cotion inventories, plants often carried large finished-goods preferred to ship soon after completing nrotu Case 21 Aurora Texsile Company 317 or not. On average, I will have about three months of cotton at as low as 20 days when the running hot the plant, but that will fall cotton prices hit low points. Give cotton market is running hot and as high as 120 days when Zinser would actuall n my cost-minimizing strategy. I don't see where the y reduce the cotton inventory. I'm focused on the price of cotton much more than the rate at which we use it in the plant. The Decision Michael Pogonowski had to decide whether the company should purchase the Zinser or keep using the existing ring-spinning machine. Beyond this specific investment decision, he wondered whether it was in the shareholders' best interest to invest in Aurora when both the company and the industry were continuing to lose money. Ihis was particularly troublesome when he considered that the U.S. textile market would likely experience intense competition when the WTO lifted the ban on quotas in January 2005, which would only worsen Aurora's financial condition and its credit rating of BB, already below investment grade (Exhibit 7). Pogonowski was also con- cerned about the higher liability risks associated with customer returns in the hig end market, where most of the new yarn would be sold. For example, if the frequency of customer returns remained at the current level of 1.5%, it would compromise Aurora's ability to realize the premium margins that had originally attracted the com- pany to enter the segment. h- Pogonowski was sensitive to the fact that, over the past four years, shareholders had seen the value of their Aurora holdings fall from about $30 a share to its current price of $12. In light of such poor performance, shareholders might prefer to see the institution of a dividend rather than see money spent on new assets for Aurora. Nev- ertheless, if buying the Zinser could reverse the downward trend of Aurora's stock price, then it would clearly be a welcome event for the owners. Aurora used a hurdle ate of 10% for this type of replacement decision. Pogonowski felt confident that the inser would return more than 10% over its expected life of 10 years, but he was less onfident that Aurora would be able to remain in operation over that time span. 8 Part Four Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocation EXHIBIT 1 Consolidated Income Statement for the Fiscal Years Ended December 30, 1999-2002 (dollars in thousands) 20002001 1999 187,673 190,473 151,893 Pounds shipped (000s) Average selling price/lb. 1.2064 1.2045 1.02 1.3103 0.4447 0.4421 0.44650235 0.7077 0.6429 0.6487 0.450 Conversion costlb. Average raw-material costlb. Net sales Raw-material cost Cost of conversion $245,908- $229,787 $182,955 98,536 $147 132,812 122,461 84,212 23,114 14,218 83,454 84212 67.822 61 Gross margin SG&A expenses Depreciation and amortization Operating profit 29,641 14,603 15,241 16,597 13,005 (203)(4,109) 6,773 1,143 11,196 (6,234) 5,130 (1,232) 4,758 Interest expense Other income (expense) Asset impairments 6,777 3,440 7,564 Earnings before income-tax provision (6,980) (9,739)(17,354) (10,968) Income-tax provision @ 38% tax rate Net earnings (2.513) (3,506) ($4,467)($6,233) (6247) (3.949) ($7,020 ($11,106) Costs assoclated with the shutdown of plants. Consolidated Balance Sheets as ot December 30, 1999-2002 (dollars Case 21 Aurora Testile Company 319 2 Accounts receivable, net 11,663 Total current assets Less accumulated depreciation (146,302) Other noncurrent assets $1 $164,890 $143,023 Accrued compensation and benefits Other accrued expenses Current portion of long-term debt Other long-term liabilities Shareholders' equity Common stock, par $0.01 Total shareholders' equity Total llabilities and shareholders' equity $135,991 $164,890 tal Budgeting and Resource Allocation pehur 320 EXHIBIT 3 1 Production Facilities Count Range Product Mix 100% Cotton 100% Cotton Heather and Poly/Cotton Blends 5/1 to 22/1 5/1 to 22/1 8/1 to 30/1 5/1 1o 30/1 Plant Ring Hunter Rome Barton ,00% Cotton Rotor I Industrial Yarn Production EXHIBIT 4 SpinningWinding Combining the Slivers (Drawing Combing/Roving) Carding Blending Line Line Cotton was shipped to the mils in bales and still contained vegetable matter. An automated take small tufts of fibers from the tops of a series of 20 to 40 bales, opened or separated the g and blended the tufts for a more homogeneous product clumps," removed any foreign particles in the tufts, a was a continuous flow of fibers from the Opening Line to the Card. Carding The Card received the smal tufts of fibers from the Opening Line and, through a series of metallic cylinders, separated the tufts of fibers into indlividual fibers, which were parallelized, cleaned to foreign particles, and formed into a strand of parallel fibers, called a sliver. The strand resembled a large, un- twisted rope. Drawing The Drawing Combing The Combing Process was an optional process for ring-spun yarns. Combing removed short fibers (8%-12% d the weight of a sliver), eliminated practically all remaining foreign particles, and further blended the stock. Roving The Roving Process reduced the weight of a drawn sliver to the point that a small amount of twist was needed tb provide the tensile strength required for ring spinning. Process combined six to eight slivers to allow greater uniformity of the drawn sliver. Ring Spinning Ring Spinning further reduced the weight (linear density) of the strand of roving, added more twist, and creete small package weighing less than half a pound. Winding that simply took multiple packages of ring-spun yarn and "spliced them together in continuous strand, resulting in a package of yarn weighing three to four pounds. Case 21 Aurora Testile Company32 EXHIBIT5I Cost of Customer Returns Existing Machine Calculation Price of yarn sold Reimbursement cost $5.0 $25.0 (25/5) 5.0 1.50% 7.50% Returns as % of volume Returns as % of Returns as costib. revenue (5 x 1.5%) (7.5% x $1.023515 Calculation Price of yarn sold $10.0 $75.0 Liability multiplier Returns as % of volume Returns as % of revenue Returns as costib. (75/10) 7.5 1.00% 7.50% $0.084 (7.5 1.0%) (7.5% $ 1.02351b, x 11056) Part Four Capital Budgeing and Resource Allocation Cotton Spot Prices (1997-2002)' EXHIBIT 6 90 80 70 60 50 30 20 10 Month Source: Bloomberg Database. Interest-Rate Yields: January 2003 U.S. Government (% yield) EXHIBIT 7 Treasury bill (1-year) Treasury note (10-year) Treasury bond (30-year) 1.24 3.98 4.83 Industrials (% yield) Prime rate AAA (10-year) AA (10-year) A (10-year) BBB (10-year) BB (10-year) 4.25 4.60 4.66 4.87 5.60 6.90 The prime rate was the short-term interest rate charged by large U banks for corporate clients with strong credit ratings .S CASE Aurora Textile Company In January 2003, Michael Pogonowski, the ompany, was questioning whether the company should install a new ring-spinning machine, the Zinser 351, in the Hunter production facility. A primary advantage of the new ring spinner was its ability to produce a finer-quality yarn that would be used for higher-quality and higher-margin products. The finer-quality yam would be sold in a niche market that would command a 10% increase in the selling price of yarn, which was currently $1.0235 a pound. In addition, the Zinser would provide increased efficiency as well as greater reliability, which Aurora's operations management had been requesting for many years. The Zinser's efficiency would reduce operating costs, with lower power consumption and maintenance expenses. Sales volume, however would be 5% lower than the current market, and the cost of customer returns would be higher, which, when combined with the $8.25 million installed cost, made the chief financial officer of Aurora Textile Zinser decision a difficult one. Pogonowski believed that the decision to invest in the new technology was complicated by Aurora's lackluster financial performance as well as the difficult circumstances facing the U.S. textile industry. Aurora, however, was competing in a few select markets that were likely to continue to survive foreign competition, albeit at lower margins over the long run. He also recognized that there was unlikely to be a better time to upgrade to the Zinser as its price had been increas- ing 5% annually. Not every member of the management team, however, agreed with Pogonowski's logic. Some managers were arguing that it would be cheaper to continue with the current maintenance schedule, which should keep the current spinning machine running reliably and allow Aurora to postpone replacem indefinitely The Zinser compact spinning technology was marketed under the trademark CompACT3. Based on "Aurora Spinning Mills," an unpublished case by Robert Barnhardt (Dean Emeritus of the College of Textiles, North Carolina State University), this case was written by Lucas Doe (MBA/ME '04), under the supervision of Professor Kenneth Eades, as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Although the case is based on an actual company many of the names and much of the data have been disguised for pedagogical purposes. Copyright 2007 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rghts reserved. To order usinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be repro- 312 Part Four Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocation Aurora Textile Company was a yarn manufacturer established in the o service both the domestic and the international textile industry. Aurora's f The Company early 1900 ucts were cotton and synthetic/cotton blend yarns that were sold toP and industrial-goods manufacturers that sold their products mainly in U.S, wovens, and industrial and specialty products. Although each of these both domestic and international components, 90% of the company's reve from the domestic textile market. markets enue canie revenue volume primary consumer products were athletic and dress socks, with white ath accounting for the majority of sales. In fact, Aurora was the largest vl soc ducer of all cotton yarns for white athletic socks in the United States, with Yarn sales for the hosiery market accounted for 43% of Aurora's half the U.S. population owning socks made with Aurora yarns. Auroa enjoyed supplying the hosiery market for several reasons. First, as a l market, Aurora was able to command attractive margins and maintain re in the with some of the largest and most profitable hosiery companies in the world. Secm hosiery was produced using bulky, heavy yarns. Aurora's plants were designed for this type of manufacturing operation, which allowed the company to process lage quantities of yarn efficiently. Third, unlike other segments of the textile industry the hosiery market had successfully defended itself against global competition. The heavy yarns and bulky products were costly to transport, making them less attrac tive for foreign producers. Moreover, this type of production was highly automated in the United States such that labor costs had been reduced to the point that Asian manufacturers did not have sufficient opportunity to provide significant cost savings over U.S. manufacturers. The knitted-outerwear market was the second-largest revenue source for Aure accounting for 35% of sales. Aurora's customers within this market mainly produced knitted cotton and polyester/cotton dress shirts for a variety of major retailers. The yarns produced were medium- to fine-count yarns (14/1 to 22/1 ring and rotor). Tis quality yarn, however, was easily produced by other market participants, leaving ver little opportunity for suppliers to differentiate their products and creating an envine ment where there was constant price pressure on outerwear yarns. atively small but important segment for the company. Most of these yarns lower-cost producers, most weavers continued to purchase U.S. yarns in Accounting for 13% of Aurora's business revenue, the wovens market was a red used to produce denim for jeans. Although much of the production had shifted ofshoc- order to avoid addition, the the supply risks associated with sourcing yarns from other countries. In yans produced for the wovens market were coarse (5/1 to 14/1 ring and roton The coarseness of a yarn was measured by the amount of yarn it took to equal 0 per pound, the finer the yarn. One "hank hrld 810 Case 21 Aurora Texile Company 313 were cost efficient to produce in Aurora's manufacturing facilties this market. ment believed that the company had an excellent opportunity for grow Industrial and specialty products constituted the remaining 9% These yarns were used to produce medical vinyl-coated fabrics, and protective clothing. Because the yarn comp these products was very small, it segment provided the highest margins for Aurora, wlich made nity for growth. facilities. Aurora manage- th in this market. of Aurora's revenue. supplies, industrial adhesives, rubber- and nent of many of was not a high-volume business. Nevertheless, this Aurora used rotor- and ring-spinning production processes, although rotor spin- was also called "open-end" spinning, had constituted the majority of the enue for many years. (Exhibits 1 and 2 present Aurora's financial ning, tatements for 1999 through 2002.) The steady decline in sales had led to manage- ment's decision to close four manufacturing facilities in 2000 in an effort to rightsize Aurora's capacity to the shrinking textile market and reduce manufacturing costs. In January 2003, the company had four plants operating: Hunter, Rome, Barton, and Butler (see Exhibit 3 for product mix, capacity, and process technology by plant). The Textile-Mill Industry The U.S. textile-mill industry had experienced dramatic changes over the years because of globalization, U.S. government trade policies, cheaper production costs overseas, and customer preferences and fads. The industry, which had started in New England, moved to the southern United States to take advantage of cheaper produc tion costs. In more recent years, the search for cheaper production costs had begun to move the textile-mill industry to Asia. As more apparel makers moved their duction abroad, the yarn makers followed suit. Thus, U.S. yarn manufacturers were declining in number while facing tougher and tougher competition from the influx of imported yarns. At the same time, the strong U.S. dollar had made it more appealing for some foreign textile manufacturers to export aggressively, flooding the U.S. mar- ket. Companies like Aurora, which had kept their manufacturing base exclusively in the United States, were frequently forced to cut costs and modernize their operations to remain competitive. Consumer preferences and fads also shaped the market. The emphasis in the industry had shifted from mass production to flexible manufacturing as textile mills aimed to supply customized markets. Firms were concentrating on manufacturing sys- tems that allowed small quantities of customized goods to be produced with minimal lead time. This change enabled apparel producers to bring goods to retailers and con- sumers in a significantly shorter time frame. Information technology allowed retailers to assess their merchandise needs rapidly and to communicate those needs through apparel manufacturers to textile firms. In general, consumer preferences had moved toward finer-quality yarn with minimum defects, and those preferences were even stronger in the high-end market. Information technology also had a downside for yarn producers like Aurora because of the liability associated with customer returns, For that was sold at JCPenney for $25 might include $5 of Aurora yarn. If the yarn was example, a dress shirt 314 Part For Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocatio required to reimburse JCPenney for the full retail price of $25, five tsuld of revenue received by Aurora for the garment. In 2002, 1.5% of the Hanean- volume had been returned by its retailers. The percentage of volume Pla defective and the defect could be traced back to Aurora, the 1.5% of the Hunter and infor ier to identify the yarn man had risen mation flow through the supply chain that made it easier to identi facturer associated with a particular garment. If Aurora began selling yarns for sen over the past few years owing to advancements in technolog the high-end market, the company's dollar liability per garment wouldnae example, if Aurora supplied the yarn for a shirt that sold for $75 at Nordstrom the fact Aurora's tomer return would make Aurora liable for paying $75 to Nordstrom despite th that Aurora would have received only $10 for the yarn used to make the shirt. production engineers were confident that the Zinser would yield such hi yarn that the volume returned would drop to 1.0%. The U.S. government's free-trade policies were implemented through the Nork (CBI American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Caribbean Basin Initiative (c These trade agreements had created a burden on the U.S. textile industry by encourae ing trade with Canada, Mexico, and Caribbean countries, which lowered the prics consumer goods in the U.S. market. This enriched trade also forced U.S. textile com panies to compete against cheaper labor, lower environmental standards, and subsidized operations. The net effect was substantially lower-priced goods for U consumers but a very difficult competitive environment for U.S.-based manufacturers For other parts of the world, the U.S. State Department had used textile and tarifs as a political bargaining tool to obtain cooperation from foreign govens ments. The United States and other countries also used quotas and tariffs as a mech protect the anism to prevent the dumping of foreign goods into local markets and to domestic industry. Recently, however, the World Trade Organization (WTO) had announced that, as the governing body for international trade, it would ban its mem- bers from using quotas, effective January 1, 2005. This move would further open the U.S. market to competition from countries beyond its immediate borders. Notwith- standing this outlook, most research analysts believed that the U.S. textile industry would grow around 2% in real terms, with prices and costs increasing at a 1% inde tion rate for the foreseeable future. Production Technology The production of yarn involved the processes of cleaning and blending. carding combining the slivers, spinning, and winding (Exhibit 4). Aurora used only rotor spinning and ring spinning in its yam production. Ring spinning was a process of inserting rwists by means of a rotating spindle. In ring spinning, twisting the yam and winding it on bobbin occurred simultaneously and continuously. Although ring spinning was mre Established through agreements and negotiations signed by the bulk of the members of the General Ape ment on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO replaced GATT in January 1995. The WTO was an ii tional, multilateral organization that laid down rules for glohal trading expensive than open spinning because of the forme's slower speed he yearn equired from ring spinning was better. The additional processes (roving for ring spinning made the process more costly per pound produced. and winding) required Rotor spinning inserted twists by means of a rotating which the fiber was admitted. In "open-end" spinning, air cdistributed in a carried fibers to the perimeter of the rotor, where they were small group. The tails of the fibers were twisted together by the rotor as the yam was continuously drawn from the trifugal force the spinning action of center of the rotor. The process nating the need was very efficient and reduced the cost of spinning, in part, by elims roduced yarn Moreover, the yarn from open- t and for roving. At a speed of 60.000 rotations per n a rate three to five times higher than ring spinning. minute, open-end rotors end open-end spinning. Financial Climate spinning was much more uniform, but it was also considerably weaker and had Consequently, low-micronaire but stronger cottons were desirable for Like many of its competitors, Aurora had been struggling financially. The company had not responded quickly to the deteriorating business environment, and had suffered consecutive losses for the past four years (Exhibit 1). Currently, the company had limited cash available and had trouble maintaining sufficient working capital. Since 1999, about 150 textile plants had been closed in the United States, and 200,000 indus- try jobs had been lost. Aurora had closed four inefficient manufacturing operations, and was evaluating the performance of its remaining facilities. Since 2000, the com- pany had succeeded in cutting its SG&A spending by $3.9 million. These efforts had allowed the company to continue operations, but the difficult financial environment was expected to continue to present a challenge for Aurona. The Zinser 351 The Zinser 351 would replace an older-generation spinning machine in the Hunter plant. The existing machine had been installed in 1997 and was carried on Aurora's books at a value of $2 million. If replaced, the existing machine could be sold for about $500,000 for use in Mexico. Management felt that by the time the machine believed that, with proper maintenance, the existing machine could continue to oper- ate for 10 more years, at which point the plant was expected to have grown from its was fully depreciated in 4 years, it would have no market value. Management also current production level of 500,000 pounds a week to its capacity of 600,000 pounds a week Micronaire was a quantification of fiber fineness as measured by air permeability of a fiber sample. A sample of fine fibers would have a high ratio of surface area to mass, allowing less airflow and resulting in a lower micronaire reading. Conversely, a sample of coarse fibers would exhibit a low ratio of surface area to mass, allowing more airflow and resulting in a higher micronaire reading. 316 Part oar Capital Budgcing and Resouce Allocation require the p. chase of a machine with 35,000 spindles at a cost of $8.05 mil which point it would have zero book value, but was expected to the suitability of Hunter's ventilation, materials-flow, and inventory s To match the current production capacity of the Hunter plant would In would be an installation cost of $200,000, for a total capitalized cost of sa The new spinning machine would be fully depreciated (straight-line) in realize sold on the open market. Aurora had already spent $15,000 on marketin The cost structure of a textile plant was primarily composed of duction and overhead costs. In 2002, the Hunter plant's conversion cost although the current operators would need to be trained on the Zinser, ata tests systems gauge customer interest in its yarn as well as $5,000 on engineering tests reseach (the cost of cotton) and a conversion cost, which included the cost of labo hls chemicals, power, maintenance, customer returns for defects, and various es labor, dyes and Most of the conversion costs would not be affected if the Zinser replaced the ing spinning machine. For example, there would be no change in the work cost of $50,000, during the installation year. A significant benefit of the Zinset hoe ever, was that it was expected to reduce power and maintenance costs equivalen a savings of $0.03/Tb. The cost of customer returns constituted S0.077/Mb. of the version costs for 2002. Based on engineering and marketing projections, Pogonow estimated that the cost of customer returns would rise to S0.084/lb. for the hiphe. quality yam produced by the Zinser. As shown in Exhibit 5, the cost per pound was influenced by the return frequency ( 10%), the liability multiplier (7.5), and the expect increase in selling price per pound (SI .0235 x 110% $1.126), Depreciation and SG&A expenses were not included as part of conversion costs. SG&A was estimatol to remain at 7% of revenues for both the existing spinning machine and the Zinser. Although the Zinser's reliability would reduce the inventory of unprocessed coton buffer stocks would be necessary to hedge against the uncertainties surrounding the cotton's timely delivery to the plant as well as slowdowns and shutdowns due to pr duction problems with the spinning machine. The Zinser was becoming widely use by many U.S. yarn producers, and had proved itself a highly reliable machine, very few production delays, compared with earlier-generation spinning machines. This dependability had allowed most manufacturers to reduce their cotton inventories w 20 days from the average of 30 days (see Exhibit 6 for cotton spot prices)*Whe asked about this benefit, the Hunter plant manager responded: My job is making profits. I just happen to do it by spinning cotton yarn. A big part of those profits comes from controlling our cost of cotton. I do that by buying large quantifes dr cotton when the price is right.If you look at my cotton inventory over the year, you witn seethat it varies considerably, depending on whether I think it's a good time to buy The installation cost included a building-modification cost of $115,000, an airflow-modification $55,000, and freight and testing costs of $30,000. In addition to cotion inventories, plants often carried large finished-goods preferred to ship soon after completing nrotu Case 21 Aurora Texsile Company 317 or not. On average, I will have about three months of cotton at as low as 20 days when the running hot the plant, but that will fall cotton prices hit low points. Give cotton market is running hot and as high as 120 days when Zinser would actuall n my cost-minimizing strategy. I don't see where the y reduce the cotton inventory. I'm focused on the price of cotton much more than the rate at which we use it in the plant. The Decision Michael Pogonowski had to decide whether the company should purchase the Zinser or keep using the existing ring-spinning machine. Beyond this specific investment decision, he wondered whether it was in the shareholders' best interest to invest in Aurora when both the company and the industry were continuing to lose money. Ihis was particularly troublesome when he considered that the U.S. textile market would likely experience intense competition when the WTO lifted the ban on quotas in January 2005, which would only worsen Aurora's financial condition and its credit rating of BB, already below investment grade (Exhibit 7). Pogonowski was also con- cerned about the higher liability risks associated with customer returns in the hig end market, where most of the new yarn would be sold. For example, if the frequency of customer returns remained at the current level of 1.5%, it would compromise Aurora's ability to realize the premium margins that had originally attracted the com- pany to enter the segment. h- Pogonowski was sensitive to the fact that, over the past four years, shareholders had seen the value of their Aurora holdings fall from about $30 a share to its current price of $12. In light of such poor performance, shareholders might prefer to see the institution of a dividend rather than see money spent on new assets for Aurora. Nev- ertheless, if buying the Zinser could reverse the downward trend of Aurora's stock price, then it would clearly be a welcome event for the owners. Aurora used a hurdle ate of 10% for this type of replacement decision. Pogonowski felt confident that the inser would return more than 10% over its expected life of 10 years, but he was less onfident that Aurora would be able to remain in operation over that time span. 8 Part Four Capital Budgeting and Resource Allocation EXHIBIT 1 Consolidated Income Statement for the Fiscal Years Ended December 30, 1999-2002 (dollars in thousands) 20002001 1999 187,673 190,473 151,893 Pounds shipped (000s) Average selling price/lb. 1.2064 1.2045 1.02 1.3103 0.4447 0.4421 0.44650235 0.7077 0.6429 0.6487 0.450 Conversion costlb. Average raw-material costlb. Net sales Raw-material cost Cost of conversion $245,908- $229,787 $182,955 98,536 $147 132,812 122,461 84,212 23,114 14,218 83,454 84212 67.822 61 Gross margin SG&A expenses Depreciation and amortization Operating profit 29,641 14,603 15,241 16,597 13,005 (203)(4,109) 6,773 1,143 11,196 (6,234) 5,130 (1,232) 4,758 Interest expense Other income (expense) Asset impairments 6,777 3,440 7,564 Earnings before income-tax provision (6,980) (9,739)(17,354) (10,968) Income-tax provision @ 38% tax rate Net earnings (2.513) (3,506) ($4,467)($6,233) (6247) (3.949) ($7,020 ($11,106) Costs assoclated with the shutdown of plants. Consolidated Balance Sheets as ot December 30, 1999-2002 (dollars Case 21 Aurora Testile Company 319 2 Accounts receivable, net 11,663 Total current assets Less accumulated depreciation (146,302) Other noncurrent assets $1 $164,890 $143,023 Accrued compensation and benefits Other accrued expenses Current portion of long-term debt Other long-term liabilities Shareholders' equity Common stock, par $0.01 Total shareholders' equity Total llabilities and shareholders' equity $135,991 $164,890 tal Budgeting and Resource Allocation pehur 320 EXHIBIT 3 1 Production Facilities Count Range Product Mix 100% Cotton 100% Cotton Heather and Poly/Cotton Blends 5/1 to 22/1 5/1 to 22/1 8/1 to 30/1 5/1 1o 30/1 Plant Ring Hunter Rome Barton ,00% Cotton Rotor I Industrial Yarn Production EXHIBIT 4 SpinningWinding Combining the Slivers (Drawing Combing/Roving) Carding Blending Line Line Cotton was shipped to the mils in bales and still contained vegetable matter. An automated take small tufts of fibers from the tops of a series of 20 to 40 bales, opened or separated the g and blended the tufts for a more homogeneous product clumps," removed any foreign particles in the tufts, a was a continuous flow of fibers from the Opening Line to the Card. Carding The Card received the smal tufts of fibers from the Opening Line and, through a series of metallic cylinders, separated the tufts of fibers into indlividual fibers, which were parallelized, cleaned to foreign particles, and formed into a strand of parallel fibers, called a sliver. The strand resembled a large, un- twisted rope. Drawing The Drawing Combing The Combing Process was an optional process for ring-spun yarns. Combing removed short fibers (8%-12% d the weight of a sliver), eliminated practically all remaining foreign particles, and further blended the stock. Roving The Roving Process reduced the weight of a drawn sliver to the point that a small amount of twist was needed tb provide the tensile strength required for ring spinning. Process combined six to eight slivers to allow greater uniformity of the drawn sliver. Ring Spinning Ring Spinning further reduced the weight (linear density) of the strand of roving, added more twist, and creete small package weighing less than half a pound. Winding that simply took multiple packages of ring-spun yarn and "spliced them together in continuous strand, resulting in a package of yarn weighing three to four pounds. Case 21 Aurora Testile Company32 EXHIBIT5I Cost of Customer Returns Existing Machine Calculation Price of yarn sold Reimbursement cost $5.0 $25.0 (25/5) 5.0 1.50% 7.50% Returns as % of volume Returns as % of Returns as costib. revenue (5 x 1.5%) (7.5% x $1.023515 Calculation Price of yarn sold $10.0 $75.0 Liability multiplier Returns as % of volume Returns as % of revenue Returns as costib. (75/10) 7.5 1.00% 7.50% $0.084 (7.5 1.0%) (7.5% $ 1.02351b, x 11056) Part Four Capital Budgeing and Resource Allocation Cotton Spot Prices (1997-2002)' EXHIBIT 6 90 80 70 60 50 30 20 10 Month Source: Bloomberg Database. Interest-Rate Yields: January 2003 U.S. Government (% yield) EXHIBIT 7 Treasury bill (1-year) Treasury note (10-year) Treasury bond (30-year) 1.24 3.98 4.83 Industrials (% yield) Prime rate AAA (10-year) AA (10-year) A (10-year) BBB (10-year) BB (10-year) 4.25 4.60 4.66 4.87 5.60 6.90 The prime rate was the short-term interest rate charged by large U banks for corporate clients with strong credit ratings .S

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started