Question

Write a 5 page report answering all these questions: Is the market of making whiskey (i.e., being a distiller without Bespokens ACTivationTechnology) attractive? What makes

Write a 5 page report answering all these questions:

Is the market of making whiskey (i.e., being a distiller without Bespokens ACTivationTechnology) attractive? What makes it attractive or not? What type(s) of innovation is Bespokens ACTivation Technology? How couldthe new technology change the industry economics? What factors have enabled the co-founders to establish the business thus far? Among the three business models, which one would you recommend, and why? What additional information would help you validate your recommended business model? How would you get that information?

Use as many concepts as you can from the following list:

Entrepreneurial Ideas Entrepreneurial Opportunities & Assessment Entrepreneurial Risk & Uncertainty Effectuation Venture capital growth Leverage Contingencies What is Innovation Sources of Innovation Types of Innovation Bias toward Innovation S-Curves Disruptive Innovation Trendspotting Primary Customers Customer Value Proposition Field research & Empathic analysis Systematic Study of Customer Needs Needs-Based Customer Segmentation Industry Analysis Design Methodologies Solution Design Prototyping Business Model Business Model Value Matrix Business Model Creation Mechanisms Business Model Analysis Framework Business Model Canvas & Lean Canvas Business Model Validation & Plan Hypotheses Testing Approaches Comparing Field Research Methods

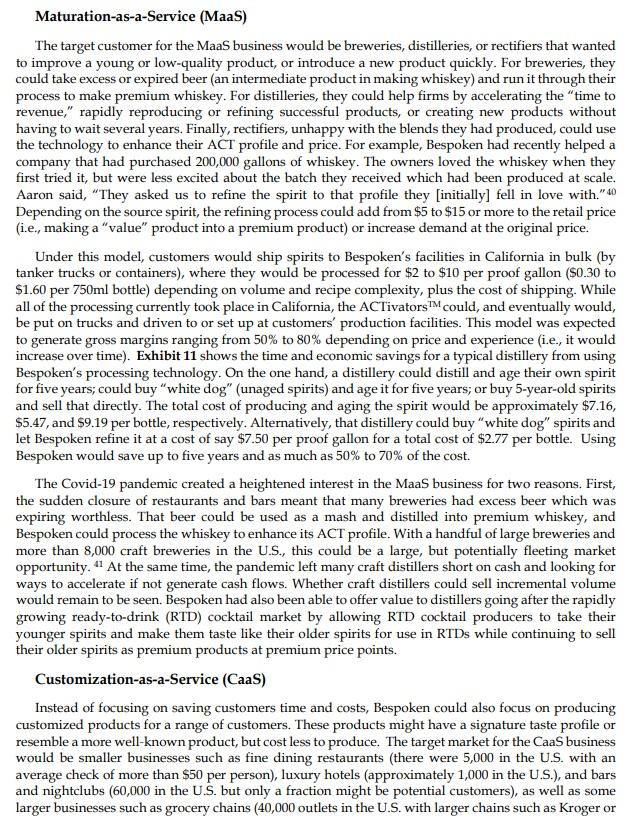

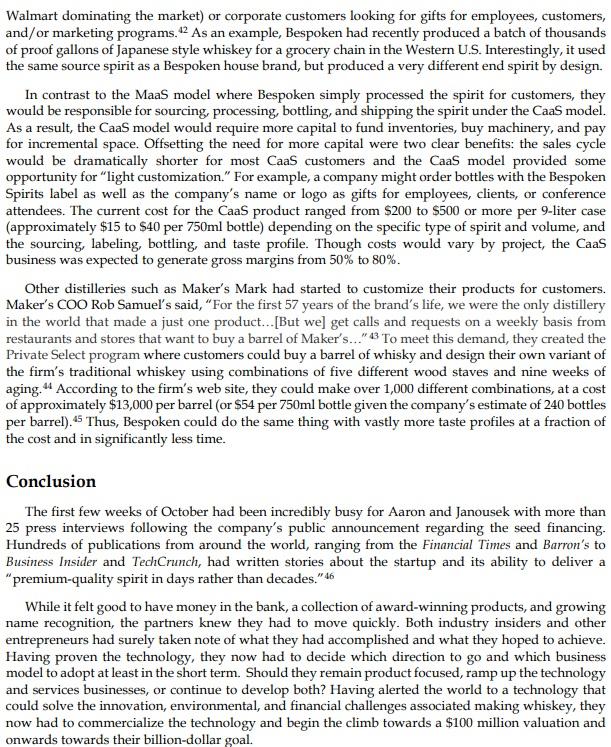

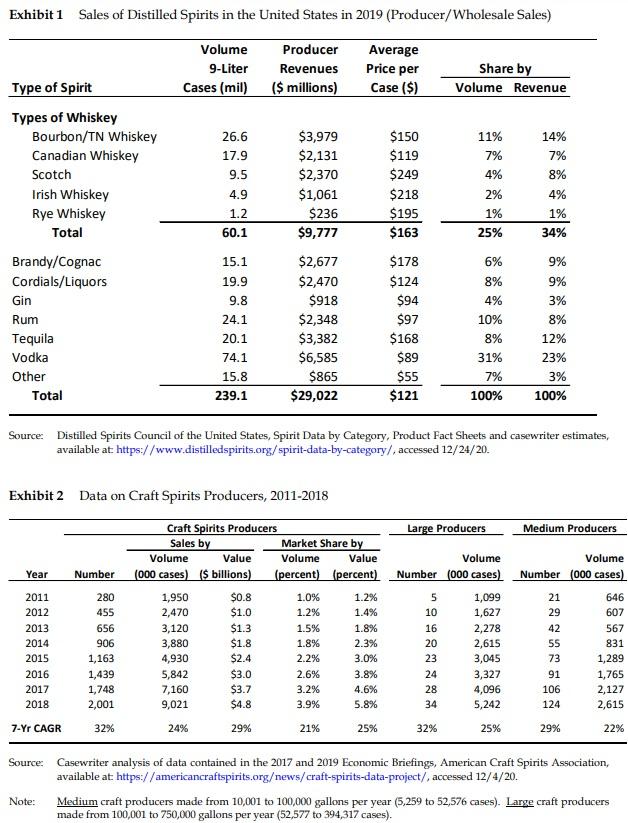

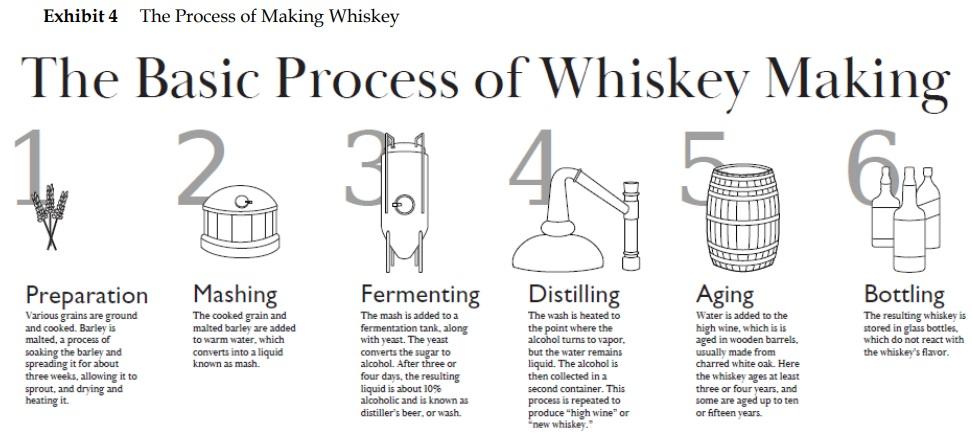

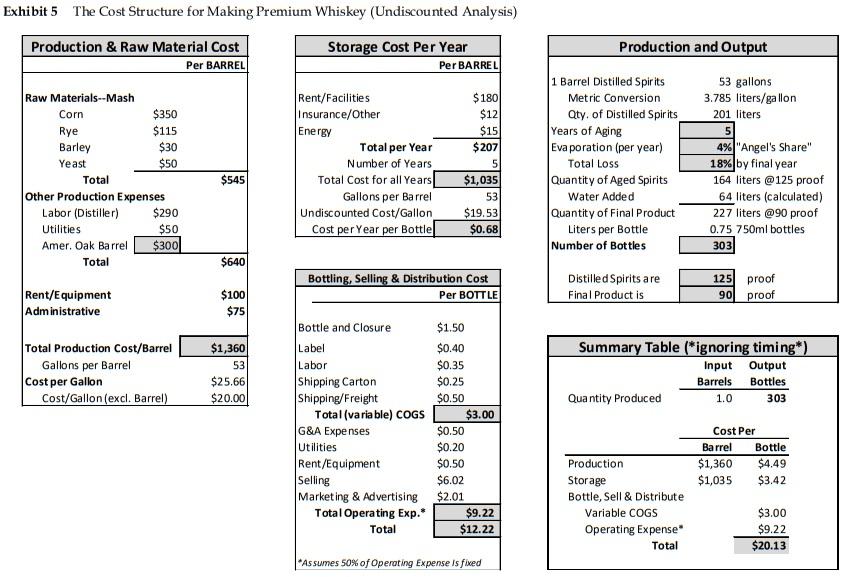

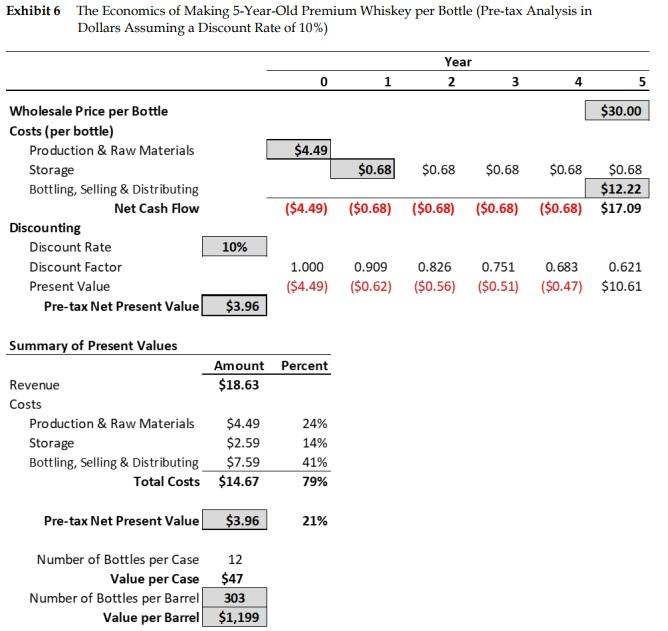

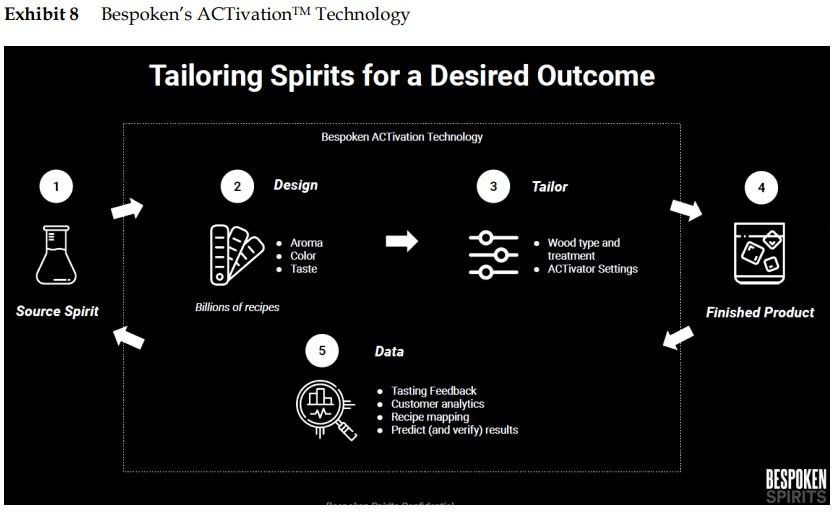

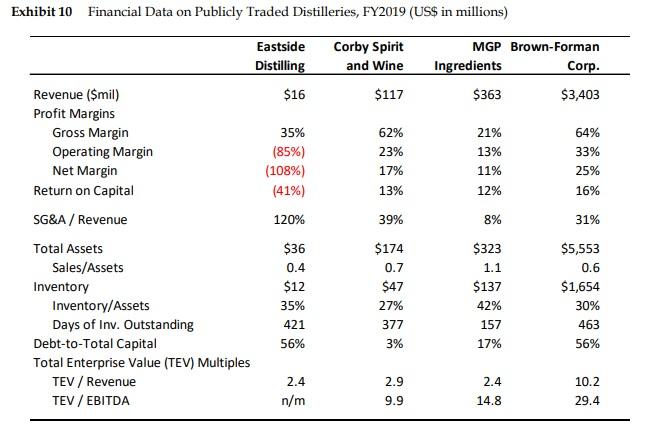

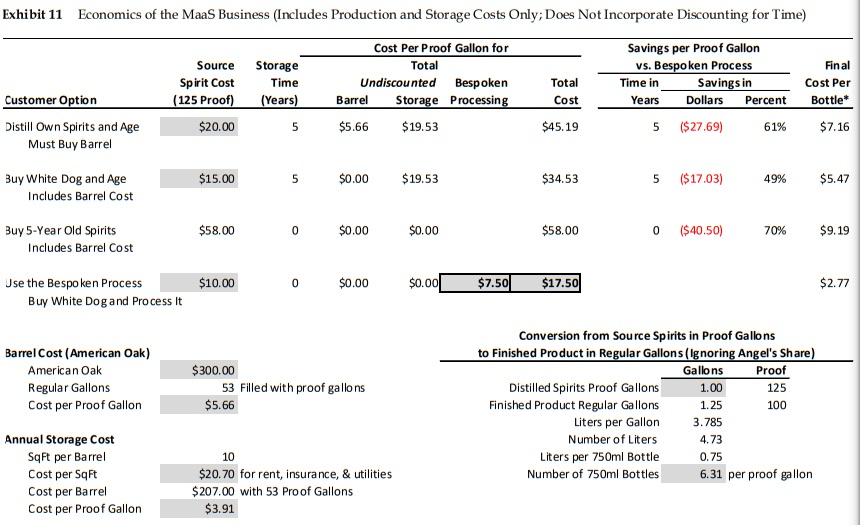

On October 7, 2020, Bespoken Spirits publicly announced it had received $2.6 million of seed funding for its "sustainable maturation process," a process that could produce award-winning whiskeys in just days rather than years. 2 Co-founders and serial entrepreneurs, Stu Aaron and Martin Janousek planned to use their patent-pending ACTivation TM technology to disrupt, in a positive way, the centuries-old distilling industry by recreating the same aroma, color, and taste that had traditionally been achieved by allowing spirits to mature in oak barrels for years if not decades. Having secured the seed financing from T.J. Rodgers, the retired CEO of Cypress Semiconductors and the owner of a well-known winery (Clos de la Tech), and baseball legend Derek Jeter, Aaron and Janousek now had to make several critical decisions regarding the company's future direction. They had already achieved their first objective: showing they could consistently produce whiskey with desired properties at scale. Perhaps the most critical question was whether they should continue making whiskey themselves or use their technology to process it for others. While the idea of creating a new line of whiskeys had its appeal and would have clear benefits, it could take years and cost millions of dollars to enter the crowded whiskey market and build a recognized brand. The alternative was to create one or more service businesses using their technology. One option, known as maturation-as-a-service (MaaS), would be to provide "accelerated aging" as a way to improve the quality, lower the cost, and shorten the production cycle for breweries, distillers, and rectifiers (companies that blended spirits distilled by others). A second option, known as customization-as-a-service (CaaS), would be to create customized products (i.e., "bespoken" products with unique taste profiles) more quickly and at lower cost for restaurants, food retailers, and corporations. These two B2B businesses would require significantly less capital and might allow them to achieve their goal of creating a billion-dollar business much sooner. The surest path to this goal, however, was unclear. At a fundamental level, Aaron and Janousek had to decide whether to be a product-based or technology-based company, or both. And if they chose to pursue the technology option, which business - MaaS or CaaS-should they prioritize? With limited resources, they knew that focusing their efforts was critical if they were going to achieve their goal. The Market for Whiskey The global retail market for alcoholic beverages was worth $1.5 trillion in 2020, and was expected to grow annually at a rate of 8%3 The total market could be divided into three categories based on the beverage's alcohol content: beer ( 4%5% alcohol by volume, ABV), wine (12%16%), and liquor or spirits (at least 20% and typically 35%55% ). 4 Spirits required an extra step in the production process known as distillation to boost the alcohol content. The global retail market for spirits was worth $470 billion in 2020.5 Popular spirits included vodka, gin, rum, tequila, brandy, and whiskey - the last five of which were either sometimes or always aged in barrels. Exhibit 1 shows the major segments of the U.S. spirits market by volume and producer revenues. Sales of all spirits combined were 239 million cases worth $29 billion (the standard measure of volume was 9-liter cases typically consisting of twelve 750ml bottles). For whiskeys in particular, sales were 60 million cases worth almost $10 billion. The U.S. whiskey industry could be divided into three segments: producers, distributors, and retailers. Until 2005, companies could not participate in more than one segment of the value chain (i.e., producers could not distribute alcohol or sell products to consumers). Although the regulations had changed, the industry remained relatively segmented and prices were marked up as products passed through the supply chain. For example, a producer might sell a bottle of premium whiskey for $30 to a distributor, who would sell it to a retailer for $42, who would, in turn, sell it to a customer for $60, thereby generating gross margins of 30%[( price - cost ) /price )] for distributors and retailers. Whiskey production was highly fragmented yet "dominated" by a few large producers (also known as distillers). The largest companies were Diageo with global sales of $16.8 billion in 2019, Beam Suntory ( $10.7 billion), Pernod Ricard ( $10.6 billion), Bacardi Limited ( $4.6 billion), and Brown-Forman (\$3.0 billion). 6 Despite their size, the top three firms controlled just 12% of the spirits market and each of them produced multiple popular brands of whiskey. 7 Diageo produced Crown Royal, Seagrams 7 , and Johnnie Walker; Brown Forman produced Jack Daniels (the largest whiskey brand in the world), and Beam Suntory produced Jim Beam, Maker's Mark, and Canadian Club. Smaller, "craft distillers" had begun to appear in the late 1990s, following the rapid rise of craft breweries. By 2019, there were more than 2,000 craft distillers operating in the U.S. (see Exhibit 2). Occasionally, very successful craft distilleries were acquired by larger firms. For example, High West Distillery, a 10-year-old company with annual sales of 70,000 cases, was acquired by Constellation Brands in 2016 for $160 million. 8 Producers created products that were differentiated by their ingredients (e.g., corn vs rye), location (e.g., Ireland, Scotland, or the U.S.), and the time spent aging in barrels. To be called Scotch, for example, a "whisky" (spelled without an " e " for products made in Scotland, Canada, and Japan) had to be made from malted barley and aged in barrels for at least three years in Scotland. 9 The products were also differentiated by price from a low of $10 for a bottle of Canadian Mist Blended Whisky to a high of $27,500 for bottle of Yamazaki 55-year-old Japanese whisky. 10 Exhibit 3 shows the price segments for American whiskeys. The categories ranged from the value segment with retail bottle prices of under $12 to the super-premium segment with bottle prices above $35. Distillers sold products to one or more of the 1,600 distributors (or wholesalers) in the United States. 11 Unlike the producer segment, however, the distribution segment was highly concentrated: the top two distributors controlled more than 50% of the market; the top 10 firms controlled nearly 75%.12 Distributors, in turn, sold products to hundreds of thousands of retail outlets. These sales were traditionally divided approximately equally between two channels: "on-premise" (i.e., bars, hotels, and restaurants) and "off-premise" (i.e., liquor stores and grocery stores) consumption outlets. The Process for and Challenges of Making Whiskey The basic process for making whiskey had not changed in more than 300 years. It began with a "mash," a cooked mix of grains like corn, rye, or malted barley (see Exhibit 4). The particular mix determined the type of whiskey: bourbon, for example, was made with at least 51% corn while rye whiskey was made with at least 51% rye. Producers then added yeast and let the mixture ferment for several days. This process produced a "wash" (also known as "distiller's beer") with an alcohol content of 7% to 10%, which was then distilled. Distillation involved heating the liquid to create a vapor and then cooling the vapor to produce a liquid with higher alcohol content. Because alcohol had a lower boiling point than water, the condensed vapor had a much higher alcohol content often as high as 140 "proof." a Once distilled, the spirit (also referred to as "white dog" or "unaged" whiskey) was diluted with water down to 125 proof and stored in oak barrels to age for as few as two or three years and as many as 50 years. Prior to filling the barrels, they were heated or "toasted" to draw sugars out of the wood and then charred (burned) to enhance the whiskey's aroma, color, and taste as it aged. The cost of a typical 53-gallon barrel (200 liters) made from American oak was $300 while one made from French oak was $700 when purchased in bulk. 13 Once the desired aging process was complete, the whiskey was diluted again, usually to somewhere in the range of 80 to 100 proof, and bottled for sale. There were a variety of chemical, financial, and environmental challenges associated with making whiskey. Gary Spedding, a Ph.D. chemist who studied the whiskey-making process, noted that many distillers had tried and abandoned efforts to accelerate the aging process. In one article, he wrote: An incredible amount of biochemistry, chemistry and phyysics is involved in maturation of distilled spirits...Multiple attempts have been made and many fancy systems have been applied by distillers to try to beat Mother Nature and Father Time in producing "matured" spirits in "rapid time" ... Hundreds of compounds with differential solubilities and reactivities are present in the barrel-aging spirit. Altering one chemical component's concentration has multiple ramifications within the chemical system...If the attempt, via the use of modern processing technologies, is to produce a tasty product acceptable to the consumer, with many of the required attributes present in a reasonable harmony, then there is nothing wrong with that approach. To say they have reproduced a fully authentic and identical-tasting product to one matured over an extended aging period is a completely different story. 14 Because the process was so complex, it was difficult to know how a batch would turn out at some point in the future. Given the lengthy barrel aging process (three to 50 years), it was extremely difficult to create new products with specific taste profiles particularly if consumers' tastes were changing over time. As a result, the established producers stuck with time-tested recipes and processes, which meant that consumers tended to "drink their father's whiskey." (Historically, more consumers were male). As a result, and much like the biotech industry, the large producers typically let smaller craft producers experiment with new products and then bought the most successful ones. Besides complex chemistry, the barrel-aging process also presented a number of financial challenges. First, it took a long time. The combination of large upfront costs and distant revenues made it difficult to sustain operations in early years with negative cash flows, and created a relatively a Proof referred to the alcohol content by volume: AVB = Proof / 2. A "proof gallon" (a standard measure) was defined as one gallon of spirits at 100 proof, or 50% alcohol by volume. A gallon of distilled spirits that was 160 proof ( 80% alcohol and equal to 1.60 "proof gallons") could be diluted with a second gallon of water to produce two gallons of 80 proof ( 40% alcohol) spirits. unattractive economic model at least in a present value sense. Exhibits 5 and 6 show a simplified economic analysis and discounted cash flow model, respectively, for producing premium whiskey. Assuming a 10% discount rate, a typical mid-sized producer could expect to earn approximately $4 in present value by making and selling a $30 bottle (wholesale price) of 5-year-old whiskey. Of course, a new producer would have to sustain five years of losses along the way, but might be able to sell an aged whiskey at a higher price, typically $3 to $5 more per bottle per year of aging. 15 A second financial challenge was that the product disappeared over time: a small percentage of spirit-colloquially known as the "angel's share" - would seep into the wood and evaporate each year. Depending on the type of wood, temperature, and barrel size, approximately 4% of the spirit evaporated every year and as much as 10% might disappear in the first year. 16 Across five years of aging, one could expect to lose as much as 20% of the whiskey, and up to 50% over 20 years. Finally, the process had environmental challenges: the barrels were often used only once to make whiskey. They could be reused for other types of spirits, but with much less impact from aging process; used to flavor other foods such as syrup or jams; used as fuel to impart a specific taste; or discarded. Having to discard one of the most expensive inputs in the production process was wasteful and costly. Consumer Trends Affecting the Whiskey Market The Bespoken Spirits team believed their products would benefit from four consumer trends currently affecting the whiskey market. First, more people, especially younger people were drinking liquor rather than beer or wine. According to one survey, 50\% of Millennials (ages 24 to 39 in 2020) preferred liquor compared to only 35% of Boomers (ages 56 to 74 in 2020). 17 An interest in reducing calories and experiencing more varied tastes (the "cocktail culture") were motivating this shift. Within the aggregate liquor category, the fastest growing segments were whiskey, tequila, and brandy. 18 Second, consumers, particularly tech-savvy Millennials, preferred high-priced, premium products, a trend known as "premiumization." As shown in Exhibit 3, the "super premium" segment was the smallest but fastest growing segment in the American Whiskey market. Third, there was a growing interest in new products and unique experiences. One of the most successful entrants in recent years was Fireball Whiskey, a cinnamon flavored whiskey that "Tastes like Heaven, Burns like Hell." Donna Crecca, a food service industry consultant, summarized this trend: "Millennials and Gen Z entered legal drinking age with a different palate than previous generations. They're more in tune with rich, complex, and even savory flavor profiles...[T]hey seek a more complex or unique flavor profile and authentic back story." 19 To satisfy the growing consumer interest in new and unique products, retailers and restauranteurs were experimenting with new products. According to one chef, "...you are always looking for unique and special things to bring to your guests. Being able to partner with another very creative local business to develop my own signature whiskey to serve in my restaurants was a very natural progression." 20 In addition to taste, consumers were increasingly drawn to companies with more sustainable business models. A recent Nielsen survey found that 48% of U.S. consumers "would definitely or probably change their consumption habits to reduce their impact on the environment" and Millennials were twice as likely as Baby Boomers ( 75% vs. 34% ) to change their habits. 21 Finally, younger consumers were more willing to experiment. According to Aaron, 54% of Baby Boomers knew what they wanted to buy when they went into a liquor store, while only 25% of younger generations knew. A recent survey confirmed this assertion: younger drinkers were more open to try new drinks ( 18% versus 8% of the general population), more likely to equate price with quality ( 40% versus 27% of Baby Boomers), and were "more likely to tell their social networks about their choices." 22 Company Background Aaron and Janousek met in 2006 while working together at Bloom Energy, a San Jose-based startup focused on developing fuel cells (see Exhibit 7). Aaron, a Cornell graduate with a degree in electrical engineering, had held both strategy and marketing roles in a variety of startup companies over the past 30 years. At Bloom, he was vice president of marketing and product management. After leaving Bloom in 2010, he became the chief commercial officer at Blue Jeans Network (video conferencing) and then the chief operating officer at PsiQuantum (quantum computing). His partner Janousek had a PhD in Material Science and had been vice president of technology development at Bloom. Later he became an Entrepreneur-in-Residence at Khosla Ventures and founded several technology startups. While at Bloom, Aaron and Janousek began to play golf on Saturday mornings followed by coffee and wideranging discussions. Over time, the discussions gradually displaced the golf as their friendship grew. The original idea for the company grew out of Janousek's frustration with how expensive high-end wines and spirits were. As a member of a wine and whiskey club, his inability to get really good spirits at reasonable prices raised a simple question, why not? Barrel aging whiskey was an arcane process that took a long time and added considerable expense. He said, "Fifty years ago, we put a man on the moon, but we still don't know what's happening inside the barrel, and still don't know how to make good whiskey quickly. It's a chemical process that we should be able to understand and control." Intrigued, he wondered if material science and data analytics could be used to accelerate, control, and even tailor the aging process? If so, the implications were enormous. Janousek said: "Advantage is all about the learning cycle - how fast you learn. If we could develop a learning cycle that was 100 to 500 times faster than the current producers [aging in one week rather than five or ten years] then we could dramatically change the production process, the economics, and ultimately the industry. No one could compete with us. The established producers don't have the ability to experiment quickly or with much precision. So they rigidly stick with what's worked in the past." In 2016, he started experimenting with making whiskey in his garage. Through careful analysis of the inputs and the process, he was gradually able to refine the resulting product. Yet by his own admission, the early batches were terrible. After six months and some 500 experiments, the whiskey was getting quite good. He then enlisted some knowledgeable friends to test the products. About a year later, he had a product that held up well in blind taste tests against more well-known brands. It was at this point, in late 2017, that Janousek first mentioned the idea to Aaron. Aaron recalled: "As Martin described the idea to me, I immediately thought it had all of the markings of what you look for as an entrepreneur and an investor. First, it had a massive market. Second, the market was ripe for disruption given the shifting consumer demographics and preferences. Third, it used a new technology that was differentiated and defensible. And fourth, it had a mission-in this case sustainability - that evoked passion beyond the clever business idea. With these four attributes, we knew we had something. The only question was whether we could make the technology work."23 They incorporated the company in early 2018, and named it Bespoken Spirits. As the products continued to improve, they decided to enter tasting competitions. In the summer of 2019, Bespoken's Bourbon Mash Whiskey won gold medals at the MicroLiquor Spirits Awards (June), a competition focused on emerging brands, and at the New York World Wine \& Spirits Competition (August) where it competed against whiskeys that had been aged for up to 10 years. 24 Then in March 2020, Bespoken won eight medals (two gold, two silver, and four bronze) at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition, the largest international spirits competition in the U.S. 25 These medals gave them the confidence to start selling their products at retail outlets and building the company. They pitched investors on the idea that science and technology could be used to replicate the effects of barrel aging, but with greater ability to tailor the whiskey's aroma, color, and taste (ACT) profiles. One of the first investors was TJ Rodgers who had invested in Bloom Energy. His investment in early 2019 allowed them to move the company into lab space in Menlo Park. About a year later, they invited Derek Jeter to invest given his expertise in building brands. Aaron first met Jeter when he had invested in Blue Jeans Network several years earlier. Jeter, seeing the opportunity, quickly agreed to invest. As they pitched the company to potential investors, they said the initial goal was to create a $100 million business en route to creating a billion-dollar business. Given recent acquisition pricing for spirits companies had occurred at $1,000 per case sold, this implied Bespoken would need to sell 100,000 cases per year to merit a $100 million valuation (annual sales of $35 to $40 million). As precedent, they looked at companies like High West Distillery, which sold premium whiskies at a retail price of $75 per bottle that were blends of whiskies produced by other distillers such as MGP Ingredients. 26 The acquisition of High West at $2,300 per case set the high mark for acquisition pricing. 27 Other success stories included the privately-owned Tito's Handmade Vodka and Diageo's Bulleit Bourbon. Founded in 1995, Tito's was selling 100,000 cases per year by 2005 and became the best-selling spirit in the United States by 2019,.28 Bulleit reached annual sales of 100,000 cases in 2012, 13 years after it was founded, and currently sold more than one million cases per year. 29 Over time, these companies had built strong and recognizable brands which helped drive their sales. Bespoken's ACTivation TM Technology Bespoken was not the first company to attempt to accelerate the aging process. Others had experimented with smaller barrels to increase the ratio of wood to liquid and agitation to ensure more contact with the wood. 30 Janousek believed a different approach, a much more precise and carefully controlled approach, could be used to refine a spirit while still using only traditional ingredients. The basic process involved adding a precise mixture of "micro staves" (small blocks of wood) to a source spirit and controlling the environment (temperature, pressure, agitation rate, etc.) in which the chemical reactions occurred to rapidly infuse the spirit with specific aromas, colors, and tastes (see Exhibit 8). Each micro stave contained 1/25,000 of the wood in a traditional barrel and varied by the types of wood used as well as the precise levels of toasting and charring. Janousek meticulously recorded the physical properties of all inputs and then, after three or four days of processing, the chemical composition - the "chemical fingerprint" - of the resulting spirit. Using this process, the Bespoken ACTivator TM could produce 500 proof-gallons per week. Because of the speed, they did not lose any volume due to evaporation. Equally importantly, it required less than 3% of the wood and less than 1% of the energy normally used to barrel-age whiskey. 31 Janousek was quick to note that their process did not require any chemical additives nor did it use artificial coloring or flavoring. The current ACTivator TM cost approximately $100,000 to assemble though future models would cost half as much and have ten times the capacity. To protect their technology, they had or had filed for approximately 10 patents on the equipment and the processes in an attempt to prevent imitation by competitors. Once the ACTivation TM process was complete, they asked expert tasters to assess the quality and determine how closely it matched the desired ACT profile using blind taste tests. With this feedback, they repeated the process until they achieved the desired properties. Over time, as their data base of experiments and their understanding of the process grew, the time to achieve a desired profile shrank dramatically. This meant they could quickly tailor products for specific customers and capitalize on emerging consumer trends in less than four weeks and sometimes as little as one week. Some early critics complained that accelerated aging took the art and romance out of producing whiskey. 32 Aaron disagreed: I would argue that our approach adds more romance, art, and creativity to the whisky-making process because we have a lot more levers to create customized spirits that customers want. It's like today's use of computer-aided animation versus the old hand-drawn animation. Computer-aided animation is still art, but it's so much more powerful, so much more versatile, and so much more economical than the hand-drawn method, and the industry evolved in that direction. 33 By 2020, Bespoken was producing and selling five types of whiskey and one dark rum (see Exhibit 9). These products had won 22 medals in six competitions within six months. 34 One judge at a recent competition said, "[This is a] fun craft rum with lots of spicy and darkly toasted flavors; this is a distillery to watch." 35 According to Janousek, "This is further proof that a spirits" color, aroma, and most importantly taste, can be designed and precisely controlled through science, resulting in premium spirits that can be adapted to a wide range of palates, from commercial appeal to highly discerning aficionados." 36 Despite the awards, there were the inevitable critics. For example, in an "open" tasting of Bespoken products (i.e., the reviewer knew what he was drinking), the reviewer said, "[T]his is not a bad entry for a bourbon...but there was very little that was exciting about this drink either. Easy to drink, but it tastes young." 37 And another critic said, "It's not a flavor profile I love, and it did taste a bit young. But if you placed it before me in a blind tasting, I wouldn't have guessed it was a whiskey speed-crafted via some crazy technology. "38 Acknowledging the criticism, Aaron responded this way: We take every piece of feedback seriously and it helps influence what we do going forward. Because taste is in the eye of the beholder, we're always evolving our products and methods. Part of our value is that we can create different things for different people. If a person doesn't like a bottle because it's too dry or too fruity, we can quickly create a new bottle for them or their demographic that matches what they do like. And that's exactly the power of Bespoken process, and our value proposition. When you try one of our bottles, it's just one of the over 17 billion b varieties we can make. 39 The Three Business Models When they presented the company to the public for the first time in October 2020, Aaron described Bespoken Sprits as a combination of three well-known companies: We are a cross between 23andme, Nespresso, and Impossible Foods. We're like 23andme because we're correlating customer preferences with recipes and final products which is like mapping a spirit's genome. We're like Nespresso because our machine, the ACTivator TM, takes spirit and our proprietary recipe pods and produces whiskey quickly, although obviously on an industrial scale. And finally, we're like Impossible Foods because we' re redefining an antiquated production model and creating a process that's much more sustainable. Given the new round of financing and their limited financial and human resources, they now had to decide how to proceed. Should they continue selling whiskey to consumers and/or should they sell their processing technology and services to businesses? Because their technology accelerated the aging b The 17 billion figure was based on combinations of different types, mixes, and seasoning processes for wood (seasoning could vary by process - natural vs kiln dried - and time), different kinds of raw spirits (both type and proof level), different levels and techniques for toasting and charring, different proof levels of the target spirit, and different activator settings (temperature, pressure, agitation, and time). process, enhanced the flavor profile, reduced production costs, and allowed customization, it appealed to different customers for different reasons. The question was whether they should target whiskey drinkers (a B2C company) or business customers interested in using their technology and services (a B2B company). A Product-based Company To analyze the implications of building a company that sold 100,000 cases of spirits per year, Aaron built a detailed financial model using both publicly traded companies and successful startups as benchmarks. (Exhibit 10 shows financial data for several publicly traded spirits companies.) Based on the model, he concluded it would likely take up to 10 years and require more than $100 million of investment to enter the crowded whiskey market and achieve name recognition: $40 million for marketing, $40 million for sales, $15 million for R\&D, and $20 million for general and administrative (G\&A) expenses. Although operating profits would cover much of this investment, they would still need to raise $20 to $30 million of funding depending on the growth rate and case pricing. Reflecting on the model and the histories of the successful startups, Aaron said: There's a playbook for this kind of business which we've learned by studying the success of Tito vodka, High West whiskey, and Bulleit bourbon, among others. The good thing about building a consumer business is that you control the process - there's a more known relationship between what you put in and what you get out - and you establish a brand which helps protect the business. Making whiskey has given us chance to learn about the market, explore the sales process, and understand consumer preferences. As a first-mover, we have a lot of data and accumulated knowledge, our patents, and scale as well as credibility in the market to keep us ahead of other firms. Until this point, Bespoken had developed products primarily to "prove the concept." They had convinced people that the technology worked - they could make high-quality whisky consistently and at scale, and they could tailor the process to achieve desired ACT profiles. The "go to market" strategy had them utilizing a contract bottler for production, selling to retailers via distributors, and pricing half-sized bottles ( 375ml ) for $30 each (the same retail price point as many premium whiskeys in standard 750ml bottles). At this price, a customer could try a single bottle at a reasonable $30 entry price point or two different types for the same $60 price they would pay for one bottle of another premium brand. With an equivalent retail price of $60 per 750ml bottle, Bespoken could expect to receive a wholesale price of $30 per bottle (or $360 per 9-liter case) once retailer and distributor margins were factored in. They also chose unique bottle shapes and brightly-colored labels to attract attention in advertisements and on shelves. According to the model, the business would generate gross margins in the 60% to 80% range. But given the heavy investment in sales and marketing, the operating margins would be negative for at least five to seven years. Before they could decide if this were the right direction to go, they had to answer a number of product and financial questions. First, related to their products, should they remain focused on whiskeys primarily, or expand into other barrel-aged products like gin, rum, or tequila? Knowing the keys to success were having a good product, which they did, and building a powerful and evocative brand name, what steps were needed to build the brand? With regard to finances, how much capital should they raise, when should they raise it, and from whom? A Technology-Based Company: Alternatively, they could build one or more service business based on their processing technology. Currently, they were exploring two service businesses: one based on providing maturation services (the MaaS business) and the other based on providing customization services (the CaaS business). Maturation-as-a-Service (MaaS) The target customer for the MaaS business would be breweries, distilleries, or rectifiers that wanted to improve a young or low-quality product, or introduce a new product quickly. For breweries, they could take excess or expired beer (an intermediate product in making whiskey) and run it through their process to make premium whiskey. For distilleries, they could help firms by accelerating the "time to revenue," rapidly reproducing or refining successful products, or creating new products without having to wait several years. Finally, rectifiers, unhappy with the blends they had produced, could use the technology to enhance their ACT profile and price. For example, Bespoken had recently helped a company that had purchased 200,000 gallons of whiskey. The owners loved the whiskey when they first tried it, but were less excited about the batch they received which had been produced at scale. Aaron said, "They asked us to refine the spirit to that profile they [initially] fell in love with." 40 Depending on the source spirit, the refining process could add from $5 to $15 or more to the retail price (i.e., making a "value" product into a premium product) or increase demand at the original price. Under this model, customers would ship spirits to Bespoken's facilities in California in bulk (by tanker trucks or containers), where they would be processed for $2 to $10 per proof gallon ( $0.30 to $1.60 per 750ml bottle) depending on volume and recipe complexity, plus the cost of shipping. While all of the processing currently took place in California, the ACTivators TM could, and eventually would, be put on trucks and driven to or set up at customers' production facilities. This model was expected to generate gross margins ranging from 50% to 80% depending on price and experience (i.e., it would increase over time). Exhibit 11 shows the time and economic savings for a typical distillery from using Bespoken's processing technology. On the one hand, a distillery could distill and age their own spirit for five years; could buy "white dog" (unaged spirits) and age it for five years; or buy 5-year-old spirits and sell that directly. The total cost of producing and aging the spirit would be approximately $7.16, $5.47, and $9.19 per bottle, respectively. Alternatively, that distillery could buy "white dog" spirits and let Bespoken refine it at a cost of say $7.50 per proof gallon for a total cost of $2.77 per bottle. Using Bespoken would save up to five years and as much as 50% to 70% of the cost. The Covid-19 pandemic created a heightened interest in the MaaS business for two reasons. First, the sudden closure of restaurants and bars meant that many breweries had excess beer which was expiring worthless. That beer could be used as a mash and distilled into premium whiskey, and Bespoken could process the whiskey to enhance its ACT profile. With a handful of large breweries and more than 8,000 craft breweries in the U.S., this could be a large, but potentially fleeting market opportunity. 41 At the same time, the pandemic left many craft distillers short on cash and looking for ways to accelerate if not generate cash flows. Whether craft distillers could sell incremental volume would remain to be seen. Bespoken had also been able to offer value to distillers going after the rapidly growing ready-to-drink (RTD) cocktail market by allowing RTD cocktail producers to take their younger spirits and make them taste like their older spirits for use in RTDs while continuing to sell their older spirits as premium products at premium price points. Customization-as-a-Service (CaaS) Instead of focusing on saving customers time and costs, Bespoken could also focus on producing customized products for a range of customers. These products might have a signature taste profile or resemble a more well-known product, but cost less to produce. The target market for the CaaS business would be smaller businesses such as fine dining restaurants (there were 5,000 in the U.S. with an average check of more than $50 per person), luxury hotels (approximately 1,000 in the U.S.), and bars and nightclubs (60,000 in the U.S. but only a fraction might be potential customers), as well as some larger businesses such as grocery chains (40,000 outlets in the U.S. with larger chains such as Kroger or Walmart dominating the market) or corporate customers looking for gifts for employees, customers, and/or marketing programs. 42 As an example, Bespoken had recently produced a batch of thousands of proof gallons of Japanese style whiskey for a grocery chain in the Western U.S. Interestingly, it used the same source spirit as a Bespoken house brand, but produced a very different end spirit by design. In contrast to the MaaS model where Bespoken simply processed the spirit for customers, they would be responsible for sourcing, processing, bottling, and shipping the spirit under the CaaS model. As a result, the CaaS model would require more capital to fund inventories, buy machinery, and pay for incremental space. Offsetting the need for more capital were two clear benefits: the sales cycle would be dramatically shorter for most CaaS customers and the CaaS model provided some opportunity for "light customization." For example, a company might order bottles with the Bespoken Spirits label as well as the company's name or logo as gifts for employees, clients, or conference attendees. The current cost for the CaaS product ranged from $200 to $500 or more per 9-liter case (approximately $15 to $40 per 750ml bottle) depending on the specific type of spirit and volume, and the sourcing, labeling, bottling, and taste profile. Though costs would vary by project, the CaaS business was expected to generate gross margins from 50% to 80%. Other distilleries such as Maker's Mark had started to customize their products for customers. Maker's COO Rob Samuel's said, "For the first 57 years of the brand's life, we were the only distillery in the world that made a just one product... [But we] get calls and requests on a weekly basis from restaurants and stores that want to buy a barrel of Maker's... "43 To meet this demand, they created the Private Select program where customers could buy a barrel of whisky and design their own variant of the firm's traditional whiskey using combinations of five different wood staves and nine weeks of aging. 44 According to the firm's web site, they could make over 1,000 different combinations, at a cost of approximately $13,000 per barrel (or $54 per 750ml bottle given the company's estimate of 240 bottles per barrel). 45 Thus, Bespoken could do the same thing with vastly more taste profiles at a fraction of the cost and in significantly less time. Conclusion The first few weeks of October had been incredibly busy for Aaron and Janousek with more than 25 press interviews following the company's public announcement regarding the seed financing. Hundreds of publications from around the world, ranging from the Financial Times and Barron's to Business Insider and TechCrunch, had written stories about the startup and its ability to deliver a "premium-quality spirit in days rather than decades." 46 While it felt good to have money in the bank, a collection of award-winning products, and growing name recognition, the partners knew they had to move quickly. Both industry insiders and other entrepreneurs had surely taken note of what they had accomplished and what they hoped to achieve. Having proven the technology, they now had to decide which direction to go and which business model to adopt at least in the short term. Should they remain product focused, ramp up the technology and services businesses, or continue to develop both? Having alerted the world to a technology that could solve the innovation, environmental, and financial challenges associated making whiskey, they now had to commercialize the technology and begin the climb towards a $100 million valuation and onwards towards their billion-dollar goal. Exhibit 1 Sales of Distilled Spirits in the United States in 2019 (Producer/Wholesale Sales) Source: Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, Spirit Data by Category, Product Fact Sheets and casewriter estimates, available at: https://www.distilledspirits.org/ spirit-data-by-category/, accessed 12/24/20. Exhibit 2 Data on Craft Spirits Producers, 2011-2018 Source: Casewriter analysis of data contained in the 2017 and 2019 Economic Briefings, American Craft Spirits Association, available at: https://americancraftspirits.orgews/craft-spirits-data-project/, accessed 12/4/20. Note: Medium craft producers made from 10,001 to 100,000 gallons per year (5,259 to 52,576 cases). Large craft producers made from 100,001 to 750,000 gallons per year ( 52,577 to 394,317 cases). Exhibit 3 Price Segments in the US Market for Bourbon/Tennessee Whiskey (as of 2019) The Basic Process of Whiskey Making Exhibit 5 The Cost Structure for Making Premium Whiskey (Undiscounted Analysis) Exhibit 6 The Economics of Making 5-Year-Old Premium Whiskey per Bottle (Pre-tax Analysis in Fxhihit 8 Resnoken's ACTivation'M Technolnov Exhibit 10 Financial Data on Publicly Traded Distilleries, FY2019 (US\$ in millions) Exhibit 11 Economics of the MaaS Business (Includes Production and Storage Costs Only; Does Not Incorporate Discounting for Time)Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started