In a coffee shop in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1983, four men, including Bernard Ebbers, decided to form

Question:

In a coffee shop in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1983, four men, including Bernard Ebbers, decided to form a long-distance telephone company called Long Distance Discount Service (LDDS). Their strategy was simple:

They would acquire small “mom and pop” phone companies that had been created after the deregulation of the telecommunications industry and provide the service for a cheaper cost per minute to the customer. Within 2 years, Canadian-born Ebbers became the CEO of a company that became the second-largest telecommunications company in the United States by 2002, garnering more than 60 acquisitions along the way. Ebbers’s acquisition strategy was based, in part, on his previous experience in the motel industry. He bought his first motel in 1974 in Columbia, Mississippi, and by the early 1980s, had built a portfolio of eight motels including a Hampton Inn and a Courtyard by Marriott.

Although born in Edmonton, Alberta, Ebbers had lived in California and New Mexico before settling down in Mississippi in the 1960s. After receiving a basketball scholarship, Ebbers enrolled in Mississippi College and graduated in 1967. He moved to Brookhaven, Mississippi, and moved up the ranks as a manager for a local garment manufacturer, working in the warehouse, before starting his motel empire. (Inside the WorldCom Scam. American Greed. CNBC.com)

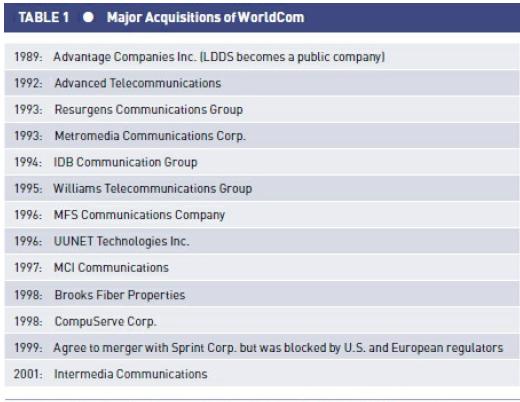

In 1989, LDDS became a public company via its acquisition of Advantage Companies. In 1995, LDDS changed its name to WorldCom, and in 1997, Ebbers earned the nickname “Telecom Cowboy” for his bid to acquire one of the largest players in the telecommunications industry, MCI. A listing of some of the acquisitions made by Ebbers is shown in Table 1. WorldCom acquired MCI on November 7, 1997, for $37 billion.

Ebbers’s Financial Problems

By 2000, Ebbers started to depend on financial support from WorldCom in the form of personal loans. In 2000, he needed to borrow more than $84 million from WorldCom to pay for the margin calls on WorldCom stock that fell from a high of $64.50 in June 1999 to $14 by the end of 2000. (Inside the WorldCom scam. American Greed. CNBC.com)

On February 1, 2002, Ebbers had to repay more than $180 million in loans from Bank of America and WorldCom, based on a $10 or less per share trigger price that had been set when he borrowed the money in 2000. Ebbers had borrowed the money to help cover a previous demand to put up additional collateral for WorldCom stock that he purchased on margin. When WorldCom’s stock price hit $9.85 per share, Ebbers owned 27 million shares. The loans were equal in value to 18.3 million shares.1 Investors were concerned about the slowdown in growth of the telecommunications industry; they were also concerned about WorldCom’s $28 billion in debt due to its aggressive acquisition strategy. But in response to rumors that WorldCom had potential accounting and financial problems in February 2002, Ebbers commented that there was no question that WorldCom was a viable company, even though it was considering writing down at least $15 billion to $20 billion in goodwill on the books based on numerous acquisitions.2 One week after the announcement of the $180 million in loans, it was reported that Ebbers owed almost $340 million from margin calls, which was significantly higher than WorldCom’s profit for that quarter, $258 million. WorldCom paid the $339.7 million that was due for repayment. The Wall Street Journal claimed that multiple loans from WorldCom to Ebbers totaling $340.8 million by 2002 could have been the largest amount ever to a top executive and was the largest in recent memory.3 Ebbers commented that he would not sell his 27,000,000 shares of stock but would sell other assets to pay off the debt.4 WorldCom stock had dropped to the $7 to $10 range during the margin calls. On February 14, 2002, WorldCom suspended three employees and froze the commissions of at least 12 salespeople based on suspicions of false order booking. The sales managers improperly altered the commissions of their sales teams, which were used to evaluate the manager’s performance. The sales teams included sales that had already been recognized by other units of the company. The legal counsel of WorldCom, Michael Salsbury, stated that there were just a few bad apples who knew how to manipulate the system. Ebbers claimed that WorldCom would be able to stand by its accounting.

Securities and Exchange Commission’s Investigation Starts On March 11, 2002, WorldCom was notified that the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) wanted information pertaining to specific accounting transactions and loans given by WorldCom to officers of the company. The SEC had asked WorldCom to voluntarily provide documentation pertaining to its results for the third quarter of 2000. The SEC was interested in examining WorldCom documents related to its wholesale accounts, sales commissions, disputed charges from customers, organizational charts, and an explanation of how it recognized goodwill. The SEC also wanted information pertaining to the loans made by WorldCom to its executives, how WorldCom was integrating its technology systems with MCI, and any state or federal government investigations that were being conducted on WorldCom.6 This request came shortly after information about WorldCom’s internal investigation of inappropriate booking of sales commissions and WorldCom’s large personal loans to Ebbers were released to the public. From a high of more than $64 in June 1999, WorldCom’s stock was now selling for less than $6.

In his response to the request by the SEC, Ebbers stated that he would be the first to tell the SEC if there were any issues that would be of concern.7 After the request had been made, the large loan to Ebbers might have given the SEC the push it needed to establish an inquiry. WorldCom stated that the loan was in the company’s best interest because Ebbers would have had to sell millions of shares of WorldCom stock to cover the margin call, which would have had a negative impact on WorldCom’s stock price. However, a former SEC enforcement official, Seth Taube, stated that a large loan to a top executive of a company automatically raises a red flag for the potential conflict of interest and breakdown of the executive’s fiduciary duty to the company’s shareholders.

Although the prevailing personal loan rates were between 9.75% and 16.67% in Jackson, Mississippi, when Ebbers received his loans, Ebbers’s loan rate was 2.14% on a $198.7 million loan and an average of 2.16% on a loan of $142.1 million. For each percentage point that the loan was below the market rate, Ebbers reduced his interest amount by $3.4 million.9 By receiving loans from WorldCom, Ebbers did not have to sell his assets to pay for his margin calls. These assets included a 164,000-acre ranch in British Columbia; a soybean farm in Louisiana; a yacht manufacturer in Savannah, Georgia; an investment in a refrigerated trucking company; and his 960-acre estate in Brookhaven, Mississippi.

The Board Becomes Involved

The WorldCom board blocked Ebbers from selling shares when the margin call came in and the stock price was in the mid-20s. Ebbers could have paid off the debt by selling an estimated 18.3 million of his 27,000,000 shares at that time. However, Ebbers did not want to sell the stock and stated that he was waiting until the stock price went up again. In March 2002, a major strategy session was called by WorldCom for all top executives around the world. However, instead of presenting a clear vision of how WorldCom should change to reverse its decline, Ebbers talked about, in part, someone stealing coffee in the break room. It seemed that the CEO of WorldCom had matched the coffee filters with the bags of coffee, and at the end of the month, the number of filters was higher than the number of bags of coffee. One of the outcomes of the meeting was “Bernie’s seven points of light,” which included having the coffee bags counted, having someone check to make sure all the lights were off before the last person left the office, and increasing the thermostat in the summer by 4 degrees to reduce energy costs. Ebbers also ordered the installation of an outdoor video camera above the smoking area so a record could be made of how long the employees spent on cigarette breaks. Ebbers also stated that all purchases greater than $5,000 must have his approval and Ebbers must personally agree to all press releases.11 On April 4, 2002, it was announced that WorldCom would lay off 4% of its workforce, amounting to 3,700 employees. WorldCom stated that the layoffs were due to the slow-growing economy and excess capacity in the telecommunications industry.12 In April 2002, WorldCom announced that Ebbers would not receive a 2001 bonus and his salary would remain unchanged at $1 million. The stock of WorldCom dropped to just above $4 as WorldCom adjusted projected sales figures from $22 billion to $21 billion for 2002 for the WorldCom Group unit. WorldCom also said it was going to review its external auditor because of the Enron scandal. WorldCom’s auditor at the time was Arthur Andersen.13 On April 29, 2002, Ebbers was forced to step down as the CEO, president, and board member of the company he cofounded after outside board members could no longer accept a declining stock price, the continued negative publicity over Ebbers’s personal loans, and the expanding scope of the SEC investigation of WorldCom. The closing price of WorldCom stock on the day of Ebbers’s resignation was $2.35.....

Questions

1. Why do you suppose Bernard Ebbers was treated more like the leader of a cult than as a CEO? Explain.

2. Evaluate the recommendations in the Breeden Report. Will these accomplish the objectives they are supposed to achieve?

3. Do you view Cynthia Cooper as an ethics exemplar in this case? Explain.

4. Arthur Andersen auditors would not speak with Cynthia Cooper, saying they reported to Sullivan. Is it correct to say that a public company’s auditors speak only with one person in the organization? Explain.

Step by Step Answer:

Understanding Business Ethics

ISBN: 9781506303239

3rd Edition

Authors: Peter A. Stanwick, Sarah D. Stanwick