On December 20, 2002, New Yorks attorney general, Eliot Spitzer, announced a ($1.4) billion settlement ending a

Question:

On December 20, 2002, New York’s attorney general, Eliot Spitzer, announced a \($1.4\) billion settlement ending a multiregulator probe of ten brokerages that alleged that

“investors were duped into buying overhyped stocks during the 90s bull market.”1 But the settlement may represent only the tip of the iceberg as aggrieved investors review the findings and sue the brokerages for redress of their personal losses estimated to be \($7\) trillion since 2000.2 Nonetheless, it promises an overdue start on the reform of Wall Street’s3 flawed conflict-of-interest practices. As such, the revisions ultimately adopted will provide a template for investment advisors around the world.

The story behind the probe is also an interesting one. It shows the capacity of a state’s Attorney-General to force the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), which has regulatory authority over U.S. capital markets, to act when they appeared reluctant to take on Wall Street in a direct, public, and serious manner. In fact, Spitzer was able to bring together his office, the SEC, the National Association of Securities Dealers, the New York Stock Exchange, and a group of state regulators, as well as the major brokerages involved, to arrange a settlement.

The accepted settlement, while indicating the complicity of the ten firms involved, will probably do more to restore lost confidence in the capital markets than to weaken it. Regulators have been seen to act, brokerages are on notice that the old practices will no longer be tolerated, and the right of investors to have unbiased advice is reinforced.

The resulting sharpening of ethics awareness on the part of advisors, their firms, and the regulators, together with the emergence of more ethical practices, should assist in the restoration of investor trust in the capital markets.

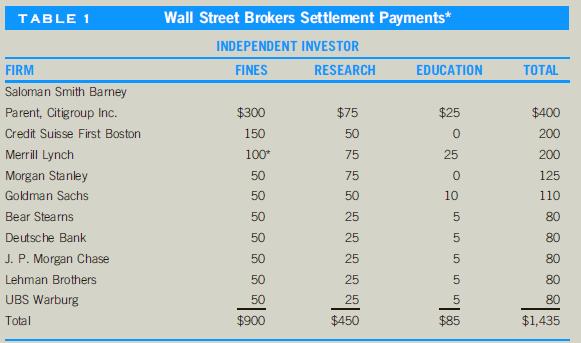

Ten firms have agreed “to pay \($1.435\) billion, including \($900\) million in penalties,

\($450\) million for research over the next five years and \($85\) million for investor education.”4 The list of payments, in millions, is shown in Table 1. Two other firms that had been part of the settlement talks did not participate in the announced settlement.

Some observers hailed the settlement and resulting changes to be “the dawn of a new day for Wall Street.”5 Others felt that the fines were a drop in the bucket. “Citicorp, for example, averaged about \($65\) million in profit each business day in the third quarter, meaning one good week would cover its payment.”6 If the payments turn out to be tax deductible, the impact would certainly be minor in size but would possess a significant signaling value.

Conflicts of interest have been common practice in the brokerage business since its inception. For example, most brokerages

(and brokers) have investments on which they take speculative positions and on which they make investment recommendations to investors. In the case of the brokerages, they are usually required to disclose to prospective investors when they are selling shares as a principal, but the presumption of unsuspecting investors has

been that brokerage employees—analysts and investment advisers—were acting in the best interest of the investors they were advising. How wrong they were!........

Questions:-

1. Identify and explain the conflicts of interest referred to in this case.

2. What additional rules should the SEC make?

3. What should be included in the investor education that the settlement funds are earmarked for?

4. Was it appropriate for the New York Attorney General’s Office to have become involved in securities regulation, or should this have been left to securities regulators?

Step by Step Answer:

Business And Professional Ethics

ISBN: 9781337514460

8th Edition

Authors: Leonard J Brooks, Paul Dunn