On November 15, 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed an enforcement action in the Northern

Question:

On November 15, 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed an enforcement action in the Northern Illinois U.S. District Court against Hollinger Inc., a Toronto-based company, and its former Chairman and CEO, Conrad Black, and the company’s former chief operating officer, David Radler.1 In the SEC’s Civil Action Complaint, the SEC alleged that during the period 1999 to at least 2003, Black and Radler engaged in a fraudulent scheme to divert cash and assets from Hollinger International, Inc., a Chicago-based company that owned newspapers such as the Chicago-Sun Times, The Daily Telegraph in London, and The Jerusalem Post, among others. Hollinger International’s Class A common stock shares were publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “HLR” while its Class B common shares were owned by Toronto-based Hollinger Inc.

The SEC alleged in its complaint that Black and Radler diverted millions of dollars for personal use by misrepresenting and omitting material facts from communications with Hollinger International’s Audit Committee and Board of Directors regarding a series of related party transactions. These men diverted cash by issuing “non-competition” payments to themselves by including disguised clauses in contracts they negotiated as part of several transactions involving Hollinger International’s sale of several of its U.S. and Canadian newspaper properties. In total, at least $85 million was diverted as disguised non-compete payments, which constituted about 14 percent of Hollinger International’s total pretax income and 340 percent of its net earnings for the three-year period from 1999 through 2001.

The fraud was fairly simple. As Black and Radler negotiated contracts for the sale of selected newspaper subsidiaries, they included a clause in each sales contract stating that neither they nor Hollinger Inc. (the Toronto owner of the Class B shares) would compete against the new owner of the newspaper for a period of time. When each transaction was settled, portions of the sales transaction proceeds were allocated to Black, Radler, and Hollinger Inc. as compensation for their willingness to not compete with the new owners of the newspaper. Thus, Black and Radler were able to take advantage of their positions within Hollinger to benefit personally at the expense of Hollinger International and its Class A common shareholders. Because of Black’s and Radler’s positions, these non-compete transactions constituted “related party transactions.” Hollinger International’s internal policies required that all related party transactions be reviewed and approved by the Audit Committee of Hollinger Internationals Board of Directors. However, Black and Radler failed to disclose and they misled the Audit Committee of Hollinger International about the non-competition agreements they negotiated on behalf of Hollinger International. In addition to their misrepresentations and failure to disclose these related- party transactions to the company’s Audit Committee for approval, Black and Radler omitted these transactions from the financial statements and proxy documents filed with the SEC. Black and Radler also attempted to disguise these payments from their auditors at KPMG, LLR In the SEC’s complaint, Stephen M. Cutler, Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement said, "Black and Radler abused their control ofa public company and treated it as theirpersonalpiggy bank. Instead of carrying out their responsibilities to protect the interest ofpublic shareholders, the defendants cheated and defrauded these shareholders through a series of deceptive schemes and misstatements."

THE TRIAL The trial began in March 2007 in a Chicago federal courtroom, more than two years after the filing of the SEC’s complaint. After months of testimony, which included a damaging confession from Black’s closest business associate, David Radler, the jury returned to the courtroom hopelessly deadlocked. Instructed by the judge to continue deliberations, the jury returned 12 days later with its verdict. Black was found guilty on four of the 13 charges against him, including obstruction of justice and mail fraud. In December 2007, Black was sentenced to 6.5 years in jail and ordered to report to prison in 12 weeks.

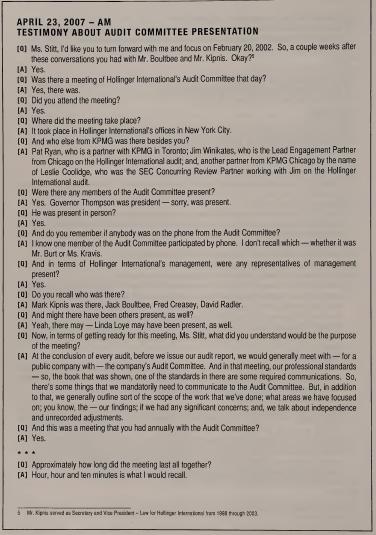

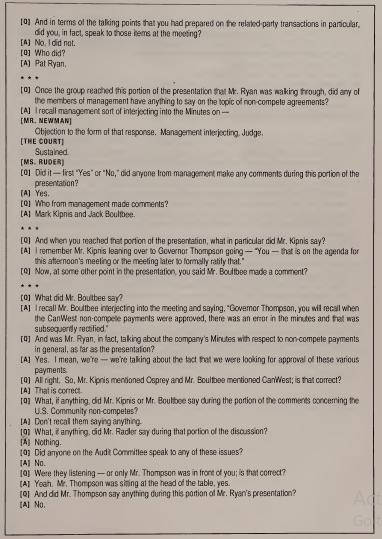

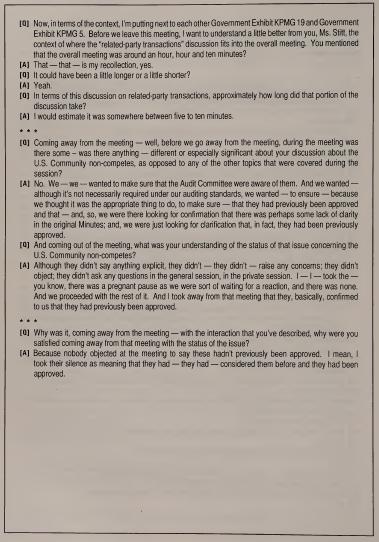

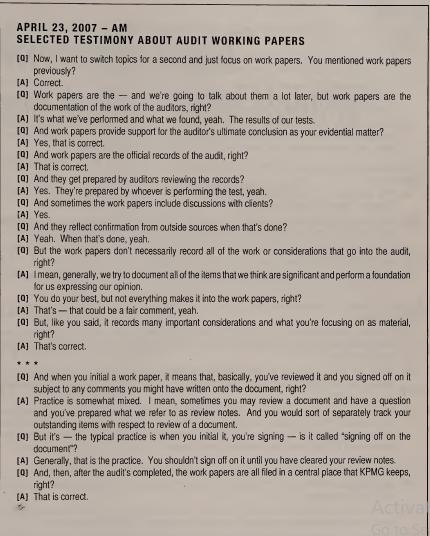

As part of the trial deliberations, representatives from KPMG, LLP were required to testify regarding numerous aspects of their financial statement audits of Hollinger Inc. and Hollinger International. The testimony provided by KPMG partner Marilyn Stitt includes information regarding KPMG’s role in performing an audit, detecting fraud, examining related party transactions, and communicating with Hollinger International’s Audit Committee...........

REQUIRED

[1] The following requirements relate to Ms. Stitt’s testimony about the concept of reasonable assurance:

[a] Research the auditing standards for “reasonable assurance” and provide your assessment as to the accuracy of Ms. Stitt’s description of that concept in her testimony.

[b] Ms. Stitt testified that audit evidence is often not conclusive. Describe the GAAS fieldwork standard related to the need to collect audit evidence and provide a summary of what is meant by “sufficient appropriate audit evidence.”

[c] As part of Ms. Stitt’s testimony, she describes auditor responsibility for detecting material misstatements due to fraud. Review AU 316, Consideration ofFraud in a Financial Statement Audit, and assess whether her testimony is consistent with auditing standards.

[2] The following requirements relate to Ms. Stitt’s testimony about the CanWest non-compete payments:

[a] The concept of a “related party” is defined by generally accepted accounting standards (GAAP). Provide a brief overview of the concept of “related party transactions.”

[b] Based on your understanding of the concept of “related party transactions,” why would the non-compete payments described in this case be considered a “related party transaction?”

[c] Summarize what the auditing standards say regarding auditor's responsibilities with respect to identifying related party relationships and transactions.

[d] What financial statement disclosures are required by generally accepted accounting standards (GAAP) for related party transactions?

[3] The following requirements relate to Ms. Stitt’s testimony about the audit committee presentation:

[a] Provide a brief overview ofthe requirements ofAU Section 380, The Auditor’s Communication with Those Charged with Governance. Be sure to describe the overall purpose of this required communication.

[b] Based on your overview of the auditor’s communication responsibilities, why was it appropriate for KPMG to discuss the related party transactions with Hollinger International’s Audit Committee?

[c] Based on your review of the transcript about the audit committee meeting, describe whether you believe KPMG exercised due professional care in pursuing this issue with Hollinger International’s Audit Committee. Did KPMG accomplish the intent of AU Section 380? What could KPMG have done differently with respect to this issue during this meeting?

[4] The following requirements relate to Ms. Stitt’s testimony about the audit working papers:

[a] Based on your review ofAU Section 339, Audit Documentation, why must auditors prepare audit documentation?

[b] Discuss the concept of “experienced auditors” as described in AU Section 339 and highlight how that concept relates to the form, content, and extent of audit documentation.

[c] Summarize the requirements in AU Section 339 for identifying the prepaper and reviewer of audit documentation. Is Ms. Stitt’s testimony consistent with those requirements? Briefly explain.

[d] Summarize the responsibilities for reviewing audit documentation as described in AU Section 311, Planning and Supervision.

Step by Step Answer:

Auditing Cases An Interactive Learning Approach

ISBN: 978-0132423502

4th Edition

Authors: Steven M Glover, Douglas F Prawitt