While Esporte Interativo (EI) had grown dramatically over the last 18 years, cofounders Edgar Diniz and Leo

Question:

While Esporte Interativo (EI) had grown dramatically over the last 18 years, co‐founders Edgar Diniz and Leo Lenz Cesar felt overwhelmed as they thought about how to maintain that growth in an increasingly competitive industry. Edgar and Leo, along with Carlos Moreira, a former partner, started EI in 1999 when the market of live sports and media in all its forms was starting to develop in Brazil. First as consultants, later as a broadcasting business, and then as a sports channel, EI endured a rough path to get to where they were, but competition against the giants, including Globo, the fourth largest media company in the world, was becoming fierce. Could they survive? What kind of resources would they need to continue growing and fend off the competition?

The Beginning of EI Leo and Carlos met during their MBA at Babson College.

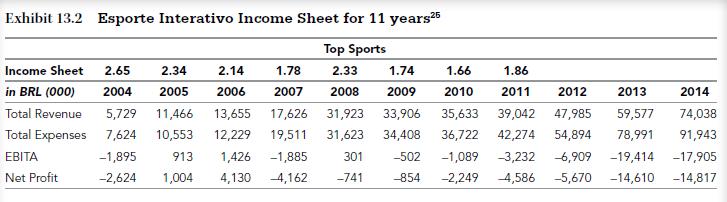

Edgar was a common friend from back home in Brazil. While all were pursing successful corporate careers, they were just counting the days until they were ready to start their own business. They had always talked about starting something in the realm of sports, and finally they each put up \($35,000\) and incorporated TopSports (the original name for EI) in the summer of 1999.

Luckily, they left their former employers on good terms and JP Morgan hired them to raise capital and improve the brand for one of their clients, Sporte Clube Vitoria, in Salvador, Brazil.

Later, they landed a series of consulting projects with Globo, such as managing a new professional soccer tournament, developing an Internet portal, and managing the sale of the marketing properties of Brazil’s most important soccer competition

(Campeonato Brasileiro).

In 2003, acknowledging that their business was heavily dependent on Globo, they decided to look for an independent opportunity. They raised nearly \($1.7\) million from 16 friends and former colleagues and approached Rede TV! with a longterm plan to start and manage their sports channel. This partnership lasted for six months. After some disagreement, they sued RedeTV!, ended up winning the lawsuit, and left for Bandeirantes broadcasting, but this time under better terms. During their two‐year contract with Bandeirantes, TopSports established ties with major mobile providers and became the only television network to offer SMS interaction with their audience, generating up to 20 million SMS responses. From 2003 to 2006, TopSports grew 522% not only due to their capacity to sell sponsorship in an innovative way but also because of their capacity to build the digital business. The Bandeirantes experience was extremely successful and a great learning opportunity. But, at the end of the day, TopSports was benefiting from a market inefficiency and Bandeirantes realized that it could replicate what TopSports was doing and therefore did not need them any longer. By the middle of 2006, TopSports, knowing that the Bandeirantes contract would come to an end soon, decided to go and build their own independent sports station.

In January of 2007, TopSports launched Esporte Interativo 24/7 with an estimated broadcast reach of 27 million households2 with the growth objective of reaching 40 of the 53 million total households in Brazil. They started generating revenue through fan‐direct programs like SMS, hotel reservations, and contests. In the first quarter of 2007, they had over six million SMS participations and about 30 million page‐views on their website.3 Their value proposition was a success, and by the summer of 2008, EI was breaking even and had attracted six major advertisers:

telcos TIM, Embratel, Gillette, Pirelli tires, DirecTV, and a manufacturer of satellite dishes. Still, they knew they had to significantly increase their media sales and distribution to achieve their profit objectives, so they came up with an aggressive growth plan that allowed them to play to their strengths.

Distribution came in three main platforms:

(a) free‐to‐air;

(b) satellite dish;

(c) pay TV.

The plan included the following:

(a) create distribution through partnerships and/or acquisitions in order to obtain broadcasting licenses,

(b) compete or collaborate with larger media companies, and

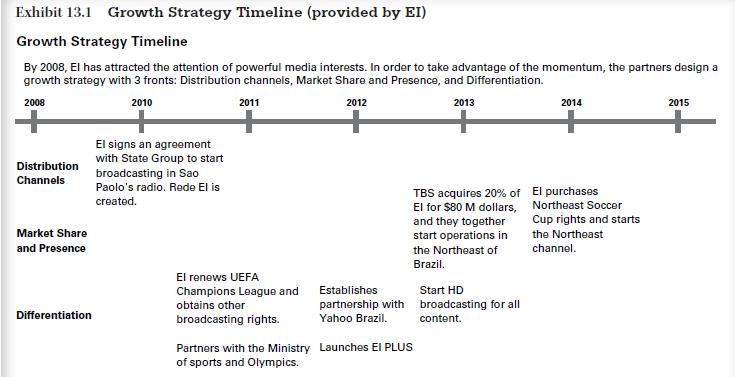

(c) differentiate by adding new and better products and services to their portfolio (Exhibit 13.1 shows IE’s Timeline).

EI Grows to a Major Player By 2010, EI revenue was starting to diversify, with 70% coming from advertising, 25% from mobile telephone services, and 5% from its virtual store shop.4 In 2011, EI regained the broadcast rights for the UEFA (Union of European Football [soccer] Association) Champions League that had long

belonged to ESPN. 5 Also, it added more tournaments like the U‐17 World Cup soccer championship, the U‐20 Football [soccer] Women’s World Cup, and the National Football League (NFL) to its portfolio. 6 In the same year, EI partnered with the Brazilian Ministry of Sports and the Olympics and Paralympics Committees to publish and promote Olympic and Paralympic Sports in 2016. These additions and partnerships allowed EI to differentiate from the competition and to broaden its target market, generating new spectators and customers. In 2012, EI partnered with Yahoo Brazil to create a portal that combined the best sport videos with top news. This allowed EI to generate more value for its customers through their website and, consequently, more traffic.

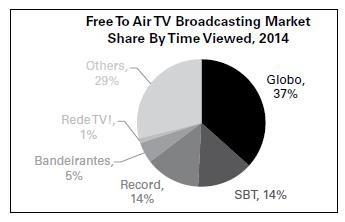

In August of the same year, EI launched Esporte Interativo Plus, a subscription‐based online service where spectators could watch complete programming 24 hours a day live or on‐demand. By the end of 2013, they started broadcasting all content in high definition (HD). 7 Overview of the Market Place As of 2014, Globo, SBT, Record TV, Rede TV!, and Bandeirantes are the top five players in TV Broadcasting in Brazil.

Together, they account for 71.1% of the free‐to‐air market share by volume and they all have sports channels.

Chart created by authors from data from http://www.bastidoresdatv.com.br/audiencia/coluna‐evolucaonacional‐das‐emissoras‐de‐tv; http://tvfoco.pop.com.br/audiencia/confira‐a‐media‐mes‐parcial‐das‐emissorase‐a‐audiencia‐por‐faixa‐horaria/ . Retrieved January 23, 2017 Sport Broadcasting has been part of Brazilian television since its origins in 1950, when TV Tupi broadcast the 1950 World Cup, the first sporting event ever broadcast in Brazil.

By 1964, pushed by the government, television became a mass medium and a new player, Rede Globo, started growing as the favorite TV partner of the State. During the 1970s and 1980s, Globo dominated the audience with a 60–80% market share all around Brazil, only competing against Tupi TV and Rede Bandeirantes, which was the first to introduce color TV to the country.8 In the 1980s, Tupi TV went bankrupt and its signal was split into two companies, which are today SBT and Rede TV!. In the 1990s, with the launch of UHF television channels, Rede Record began to air its signal. Tupi’s bankruptcy left the market wide open for Globo’s hegemony, until 2000, when preferences of the audience and technology shifted and the whole industry suffered a significant loss in viewership. The top five players lost 4.3% of share from 2000 to 2008 mainly driven by the rapid growth in Internet access.9 From 2000 to 2008, the industry underwent many changes with respect to audience preferences and technology, and the players that were able to adapt quicker were the ones to gain a competitive edge. For example, Record gained the lead over Globo during some time slots on Sunday mornings and in regions such as Rio de Janeiro because it focused programming that catered to those audiences. Globo countered its losses in free‐to‐air TV by making significant investments in pay TV, which was starting to rapidly increase in share.

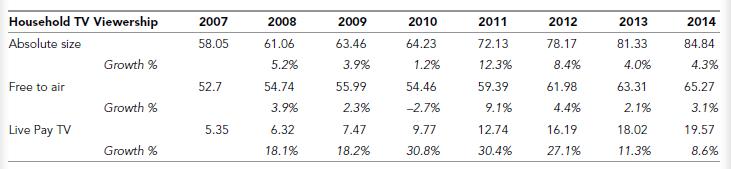

While the market share of some top players decreased from 2007 to 2014, EI increased its number of spectators substantially.

Free‐to‐air broadcasting by volume grew at 3.1% from 2007 to 2014 while EI grew over 85% during the same period.

Regarding market share of free‐to‐air TV Broadcasting by volume, Globo and Rede lost market share to SBT and others while EI gained between 1 and 3% of share. On the other hand, in market share of live pay TV by volume, big player Sky‐Direct TV was losing share to Oi, Global Village, and Telefonica. EI was growing fast and had gained access to 30% of available pay TV distribution channels since entering in 2009.

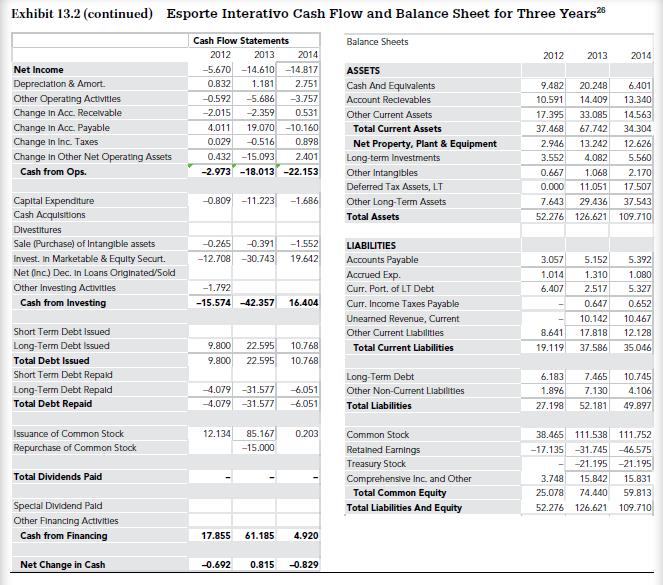

Total TV Broadcasting by number of household connections.10 Resources After almost eight years of broadcasting independently, EI barely had 3% of market share in free‐to‐air TV. Still, their financials were steady and they were profitable, but in order to continue growing, they needed cash. Pay TV had grown, gaining around 15 percentage points of market share against free‐to‐air TV11 from 2007 to 2014. EI held a strong position with EI Plus featured in Apple TV12 and other streams, but they were still competing against the same big players who had deep pockets.

EI pioneered mobile services, engaging their spectators through SMS services and this operation continued by joining the Claro TV alliance.13 The alliance allowed them to feature their content on mobile devices through an on‐demand service.

Mobile broadband reached 114 million cell phone users in 2014 growing from only 4 million in 2008.14 However, Leo noted that “while SMS was a cash cow, it was fading away. The game going forward is in social media. We’ve been aggressive in social media and we have huge audience engagement, even bigger than ESPN worldwide.”15 EI has over 100 thousand paid subscribers—or as EI call them, fans—to their social media content and over one million indirect customers annually. While EI remains innovative and differentiated, its competitors are catching up. EI holds the lead in social media followers, as they have almost twice as many followers on Facebook as Globo does.

EI was an early mover in acquiring sporting rights. In 2004, EI brought the European Champions (soccer) League and the National Basketball Association (NBA) to Brazil. Leo reminisced:

We acquired sporting rights that the big players ignored. The Champions League was ideal. Many Brazilian superstars are recruited and play for teams like Real

Madrid. We gave Brazilians a chance to watch their heroes. However, when it came time to renewing these contracts, we now had competition. We had demonstrated there was an audience for these properties and now our deep pocket foes were bidding against us.16 Prices for the exclusive rights of tournaments and other sporting events continued to increase and EI’s bargaining power was small compared to the deep pockets and dual revenue streams that the big players controlled. Specifically, the larger players not only earned advertising revenue but also revenue from cable and satellite providers to carry their channels.

The rights for the Premier League, an English professional league for men’s association soccer clubs, increased significantly and had been bought exclusively by ESPN for US\($50\) million a year through 2019, a huge increase from the US\($15\) million that ESPN and Fox used to pay.17 But EI had not been totally shut out of securing important broadcasting rights.

EI recently secured the rights for the Champions League for US\($45\) million per season through 2018, a 180% increase on the previous deal.18 Compete or Collaborate with Larger Media Companies With the cost of securing broadcasting properties escalating and the barriers to entry for EI to secure Pay TV broadcast spectrum meaning that its competitors earned money both from advertising and from Cable providers paying to carry their stations, EI faced a dilemma; should they join forces with a bigger player or try to continue independently? This dilemma was partially solved in 2013, when Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) acquired approximately 30% of EI for BRL\($80\) M19 (~US\($35\) M). Edgar noted at the time:

Having Turner as a strategic partner will significantly amplify our investment capacity and give us access to state‐of‐the‐art content production. It will also provide the opportunity to develop new business models in the dynamic environment of multi‐platform content distribution.

The size of our dream has just increased considerably with this deal.20 In the same year, EI started operations in the northeast region of Brazil.21 Later in 2014, EI bought rights to broadcast the Northeast Cup and other important tournaments of the Northeast region, and started Esporte Interativo Nordeste channel, reaching a whole new group of spectators.22 While EI’s growth and reach have been impressive, Edgar and Leo wondered how they could continue to compete with ever escalating rights prices and limited access to PayTV.

To not only survive but thrive, EI needed to grow on three main pillars.

1. Grow distribution 2. Maintain and increase content 3. Evolve on other platforms like mobile and Internet Where would the capital to grow the business come from?

TBS Offer While EI was considered an innovative leader within the sports broadcasting industry and had proven to have a loyal base of spectators, competition was straining their resources to mimic and develop new features to increase their audiences.

EI’s success had relied partly on taking advantage of the industry’s immaturity, the size of the market, and their leadership in innovation. Now that top players were catching up, EI needed a lot of capital to compete. Recognizing their need for capital, EI sought potential suitors. Hiring Goldman Sachs, EI approached Liberty, Discovery Channel, and Viacom, but the TBS offer seemed to be the best fit. TBS already owned 27% of the company and EI had a strong relationship with them. The acquisition would provide EI the resources to compete, but Edgar and Leo were reluctant to sell their “baby.” As Leo said, “EI has been our life’s work. If we are acquired by TBS, what happens to our entrepreneurial culture? Would we run EI as a separate division? Would they force us out?” Leo and Edgar wondered if they could find the capital elsewhere?

Could they raise money on the public markets? Edgar and Leo had a lot to consider before deciding whether to accept the TBS offer.

Discussion Questions

1. Describe the challenges the team faces as they design and implement their aggressive growth strategy to increase share value.

2. Describe the causes and effects of each of the three fronts of the growth strategy.

3. Does EI have what it takes to continue competing against the giants in terms of resources?

4. Is there something they can do differently?

5. Should the partners sell the company?

6. If they accept the TBS offer, what other considerations (besides price) should the founders negotiate for? How should they broach these topics in the negotiations?

Step by Step Answer: