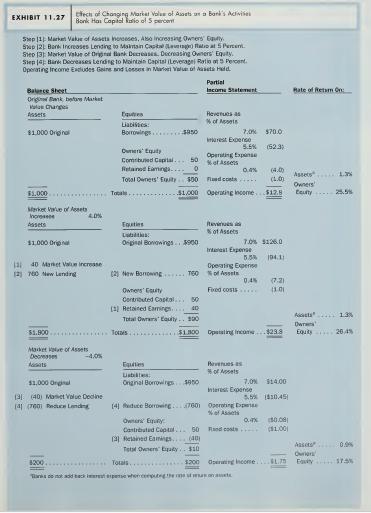

Interaction of regulation and accounting rules for financial institutions, particularly banks. Exhibit 1 1.27 illustrates the key

Question:

Interaction of regulation and accounting rules for financial institutions, particularly banks. Exhibit 1 1.27 illustrates the key features of a banking or thrift institution.

Because regulators and investors view the hanking busines.s—borrowing funds and lending them to others at higher rates—as less risky than most other businesses, they allow banks and thrifts to carry smaller shareholders' equity as a percentage of total equities than do most nonfinancial firms. That is, banks have, with the blessing of regulators, higher financial leverage than nonfinancial firms.

Exhibit 11.27 illustrates a thrift institution that regulators allow to have shareholders'

equity equal to only 8 percent of assets. (The effects illustrated here would be even more dramatic with a capital ratio of 5 percent or less, which many banks use.) Other realistic assumptions, used for illustration, are as follows:

I Liabilities can be 11.5 times as large as owners' equity; this follows from the assumption that owners' equity is 8 percent of total equities, so that liabilities can be 92 percent of total equities.

I Liabilities cost 5.5 percent (interest expense) each year.

I Assets earn 7.0 percent (interest revenues) each year.

I Variable operating expenses are 0.4 percent of total assets.

I Fixed operating expenses are 0.1 percent of the bank's starting asset position of

$1,000.

I There are no income taxes.

Key features of a hank are that ( I ) they tend to borrow funds for short terms, such as through accepting cash into checking and savings accounts or by issuing short-term certificates of deposits, while (2) they lend funds for longer terms, such as for home mortgages or customers' auto purchases.

The top panel of Exhibit 1 1 .27 shows the balance sheet for the bank as it starts in business. The firm starts with contributed capital of $80; it borrows $920, giving it

$1,000 of equities and funds available for lending. It lends $1,000, earning 7 percent on those assets. It pays interest on its $920 of borrowings, pays its operating expenses, and reports income of $14.4.

Now, let the market value of the bank's financial assets—loans—increase by 5 percent, or $50, as shown in the second panel. Show this increase on the balance sheet. The transactions are as follows:

(1) Assets increase in value by $50, so Retained Earnings increase by $50.

(2) The bank uses the extra owners" equity of $50 to borrow an additional $575

(= 1 1 .5 X $50), which it lends to new customers, increasing total assets by $575.

The income statement shows more revenues and more expenses, but rates of return change little from those of the original bank. Note, however, the effect on the bank's size: a 5 percent increase in market value allows the bank to increase its assets and size by 62.5 percent, from $1,000 in assets to $1,625 in assets. This creates no problem for the bank. Bank managers are happy because their compensation often depends on bank size, not just bank profitability.

Now, go back to the original bank and let the market value of the bank's financial assets decrease by 5 percent, or $50, as shown in the third panel. Observe this decrease on the balance sheet. The transactions are as follows:

(3) Assets decrease in value by $50. so Retained Earnings decrease by $50.

(4) The bank's decrease in owners" equity requires it to reduce borrowings by $575

(= 11.5 X $50). In order to pay back its creditors and to reduce assets, it must reduce its lendings by $575.

The income statement shows smaller revenues and smaller expenses, but rates of return change little from those of the original bank. Note, however, the effect on the bank's size: a 5 percent decrease in market value has forced the bank to

reduce its size by 62.5 percent, from $1,000 in assets to $375 in assets. This creates a major problem for the bank. The problem arises because the bank must shrink in size, by a lot and quickly. The bank's assets comprise loans it has made to customers, typically long-term loans. The bank cannot easily recall those loans without incurring significant cost. (The typical loan gives the bank's customer the right to prepay the loan whenever the customer wants but does not allow the bank to call in the loan at the bank's whim.) Perhaps the bank will have to sell its assets to others, at a loss, to raise cash to reduce its own borrowings and its size.

Whatever it does, the bank has a problem. This problem ari.ses because the bank shows the losses on its balance sheet and must reduce owners' equity because of this loss. Bankers understand this feature of market value accounting for assets, and they have, historically, been the most vocal opponents of such accounting for financial assets. For many years, bankers have prevailed in keeping the changes in market values of their assets off the balance sheet.

Many banks' assets are not marketable securities but are loans, which do not trade in the marketplace. The FASB does not require the marking to market value of nonmarketable financial assets. For such assets, banks use the amortized cost method, illustrated in Problem 11.1 for Self-Study. For marketable debt securities, the bank will use market value accounting for trading securities or the amortized cost method (debt held to maturity), depending on its holding intention and ability. So long as the bank can show that it has both the ability and the intent to hold a loan until it matures, the bank need not show changes in that loan's market value on the balance sheet.

Repeat the analysis in Exhibit 1 1 .27, using a capital ratio of 5 percent instead of 8 percent, and set the changes in market value of assets first to an increase of 4 percent and then to a decrease of 4 percent.

Step by Step Answer:

Financial Accounting An Introduction To Concepts Methods And Uses

ISBN: 9780030259623

9th Edition

Authors: Clyde P. Stickney, Roman L. Weil