In this question, we discuss the research on obesity contagion by Christakis and Fowler (2007) introduced in

Question:

In this question, we discuss the research on obesity contagion by Christakis and Fowler (2007) introduced in Section 22.5. They find that people who identify obese people as friends are also more likely to be obese.

a. Does the finding by Christakis and Fowler establish a causal link between a friend’s obesity and one’s own obesity? If not, propose a different reason for the correlation identified by Christakis and Fowler.

For the rest of this problem, suppose that the effect is causal. In other words, obesity is contagious and being friends with someone who is obese is likely to make you make you obese, even if you are thin initially.

b. Do obese people impose a negative externality on their friends? What is the externality?

c. Suppose the government actively pursues Pigouvian remedies to reduce the social loss from externalities. It taxes smoking to combat the externality from secondhand smoke. It taxes factories to reduce the environmental harm from pollution.

If the government also wants to use a Pigouvian tax to alleviate the problem of obesity contagion, what should it tax? Will this tax work? What factors go into deciding the size of the tax?

d. Suppose that people know that obesity contagion exists and can calculate the effect that obese friends impose on them. Would someone ever voluntarily befriend an obese person? What does this mean about the maximum harm an obese person can impose on his friends due to the obesity externality?

e. Obesity contagion can also travel through familial relations. Unlike in the case of friendships, family kinships – especially between parents and children – are much less likely to be voluntary. How does your answer to the previous question change for family members instead of friends?

f. Recall the concept of excess burden from Chapter 21. For both the cases of friends and family members, what is the excess burden imposed by obesity contagion?

g. Now consider the negative externality caused by a polluting factory. For the sake of this problem, assume that the pollution is concentrated and does not affect anyone or anything outside the factory’s immediate radius. Living next to the factory is voluntary, and people are not legally proscribed from moving. For a family living next to the factory, what is the upper bound on the harm caused by the pollution?

What might the excess burden be?

Data From Section 22.5:

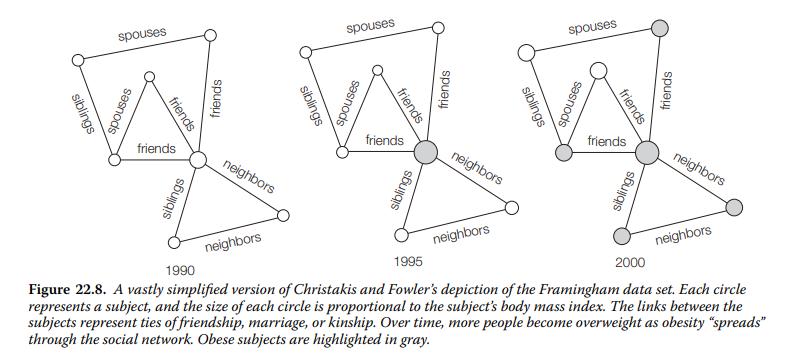

Researchers have used data from a massive study of the residents of a Massachusetts town to test whether social networks actually do spread obesity. The Framingham Heart Study was initiated in 1948 and originally included over 5,000 subjects from the town of Framingham, Massachusetts (Christakis and Fowler 2007). The offspring of these research subjects have also been included in the study, which remains ongoing. Researchers track data on subject health, but most critically they also track the social relationships between subjects. The dataset includes information on which subjects are spouses, siblings, neighbors, and data on which subjects consider which other subjects to be their friends (see Figure 22.8).

After analyzing network data on over 12,000 subjects spanning from 1971 to 2003, Christakis and Fowler (2007) find evidence for obesity contagion. They find that subjects (called egos in social network analysis) are more likely to become obese if the people that they are connected to (called alters) became obese in a previous period. If an ego identified an alter as his or her friend, and that alter became obese during the study period, then the ego’s risk of becoming obese was estimated to increase by 57%. If that alter mutually identified the ego as a friend, the ego’s risk of becoming obese was estimated to increase by 171%. Effects were smaller but still statistically significant for alters that were spouses or siblings of the egos; the only alters that did not seem to spread obesity to egos were next-door neighbors.

Figure 22.8:

Step by Step Answer: