For most consumers in developing countries, credit is an afterthought, an easily accessible component of making a

Question:

For most consumers in developing countries, credit is an afterthought, an easily accessible component of making a purchase. Credit scores are tracked and access to credit can be limited for individuals with a bankruptcy or foreclosure.

Still, for the majority of consumers access to credit is relatively easy.

Obtaining credit is a major barrier for bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers in developing markets. As much as two-thirds of the world’s population cannot obtain credit from banks. Instead, credit, if available at all, can only be accessed through loan sharks and other forms of organized crime. This debt comes with a hefty cost. Interest rates can be extremely high (Woodward, 2009).9 The lack of reasonably priced credit has implications for international marketers.

It keeps many consumers stuck in poverty. It limits purchasing power, constrains development, and is a key component of bottom-of-the-pyramid markets.

For years, individuals and groups have looked for ways to respond to the global credit access problem. In 1976, Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus came up with a solution—microfinance. On a trip to his home country, Bangladesh,

Professor Yunus conducted an informal survey of the loan shark loans to local villagers. The total amount of the average loan was a small $27. The pain associated with this debt in terms of the amount of interest charged was unequal to the value. The banks in the country would not lend to the villagers because they were not “credit worthy.” They had no collateral and low earnings. The profit on a $27 loan also seemed too small for them.

Stepping into the void in the market, Professor Yunus loaned the $27 himself.

From there microfinance was born. The concept of microfinance is simple. By fixing the institutional gap, credit can be made available to impoverished individuals. This provides them the funding needed to start businesses and earn their way out of poverty. Women are more likely to repay loans, which makes them the target market for the majority of microfinance loans.

Obtaining credit is difficult for bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers in developing markets.

Mallamma, a forty-two-year-old entrepreneur in Hyderabad, India, used a microfinance loan of 10,000 rupees to start a fish business. In one year she grew the business to the point that she sought a second loan of Rs 50,000 to hire an employee and continue expanding. In Hyderabad, another borrower, Geetawati, used an Rs 10,000 loan to buy a sewing machine after her husband passed away. In one year, she grew the business to the point that she earns Rs 100 per day and has an employee. Both women repaid their initial loans.

Professor Yunus founded the Grameen Bank, which now lends more than $1 billion each year. Ninety-seven percent of their borrowers are women, and all of the loans are self-financed, making the bank highly stable. The company also keeps costs very low. Advertising or other promotions are not used. The simple product coupled with the social goal of helping the disadvantaged allows them to be highly efficient. This efficiency has allowed the Grameen Bank to start loaning to poor consumers in many developed countries.

Microfinance has boomed in the past decade. In India alone, the sector grew at a 50% to 70% annual rate from 2006 to 2009. More than 800 microfinance institutions now operate in the country. There are 183 members of Sa-Dhan, a network of microfinance lenders, and for this group the amount of loans grew from Rs 3,456 crore to Rs 11,734 crore. Microfinance is a key component of the Indian economy. It has led to some migration from cities to rural areas to take advantage of the jobs created by microfinance (Gardner, 2008; Karlan, 2008;

Bhattacharya, 2009; Foroohar, 2010; May, 2010; Sharma, 2010).

Professor Yunus started a global movement. More than 150 million bottom-ofthe-

pyramid consumers have borrowed money from a microfinance institution.

The average microfinance loan is $1,026 and only 3.1% of loans default. The default rate is better than that for many banks lending to developed market consumers. The amount of finance tripled between 2004 and 2006 to $4 billion globally. The majority of lending goes to women and 85% of lending is conducted in Asia where the movement originated. Growth is fast in other regions, especially Latin America. Even with this growth, it is estimated that 95%

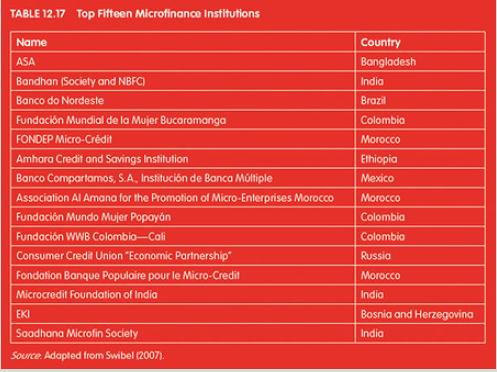

of the potential market for microfinance has borrowed money. In markets where microfinance has deep roots, such as Bangladesh, 60% to 75% of the market borrows, which suggests that there is great potential for growth. Table 12.17 lists the top fifteen microfinance institutions globally.

Questions

1. Is the goal of microfinance profit or a social benefit? Can it be both?

2. Consider how you use credit on a daily basis. How would your life be different without this credit?

3. Conduct an online search of the world’s poorest countries. Do you think microfinance will be effective in these markets?

4. What business benefits are there from increased wealth in least-developed countries?

5. Do you agree with the criticisms regarding banks moving into the microfinance market? Why or why not?

Step by Step Answer:

International Marketing

ISBN: 9781506389219

2nd Edition

Authors: Daniel W. Baack, Barbara Czarnecka, Donald E. Baack