When Charles Turner was told, on his fortieth birthday, that he was to be promoted to manager

Question:

When Charles Turner was told, on his fortieth birthday, that he was to be promoted to manager of the Electrical Insulation Materials Sales Department of Climax Fibre and Textile Company Limited, his gratification was strongly tempered by doubts about his own personal adequacy for the job.

INITIAL DOUBTS

Climax had only started to market its 'Highohm' range of electrical insulation materials two years previously. Though the Highohm products were not easy to sell - their small but definite technical advantages over competing products were more or less cancelled out by higher prices - their entry to the market had been spectacularly successful.

Existing production capacity was already almost fully sold, and a big new plant, which would more than double capacity, was under construction and expected to start up in six to nine months' time.

Turner was left in no doubt by his sales director that, as manager, he would be expected, through his small sales force, to ensure that sales of Highohm products continued to increase and that most of the extra capacity of the new plant was sold within no more than a year of production commencing. In addition, he was expected personally to service the

'house accounts' - five very large customers who between them were responsible for over 25 per cent of all Highohm purchases. The biggest of them, Bucks Electrical Cables, was reputed to be extremely awkward to deal with, and one of Turner's immediate worries in his new appointment was that he would lose this account and 10 per cent of his sales in one dreadful moment of catastrophe.

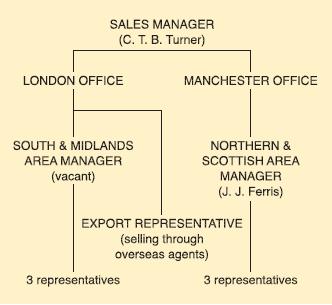

This was not his only worry. He wondered how Jim Ferris, who managed the Northern and Scottish Area, would react to his appointment. Turner did not know Ferris very well, though his predecessor as sales manager, Frank Spofforth, had often spoken of him in glowing terms. He was a self-confident man in his late twenties, reputedly very dynamic, highly intelligent, and a brilliant salesman of industrial products. He had achieved remarkable success in running the Northern and Scottish Area: 44 per cent of all Highohm sales were made there, as against only 28 per cent from the South and Midlands Area, which Turner had managed prior to his promotion.

(Remaining sales came from the 'house accounts' and from exports.) Turner, in fact, wondered why he, and not Ferris, had been promoted.

A further worry for Turner was the new plant. He had always felt that it was much too big and he was extremely dubious that more than a small part of the extra capacity it provided could be rapidly taken up in increased sales.

Most of all, however, Turner doubted his own abilities. He knew that he was thorough, methodical, painstaking and cautious, but these were hardly the qualities essential for managing a sales operation.

His caution tended to make him slow and hesitant. He rarely produced new ideas and he disliked making decisions unless he had all the facts and had gone over them several times. He thought he was by nature fitted to keep an existing successful operation going, but he gravely doubted his ability as a leader of a dynamic pioneering effort.

Turner had hoped that he would have a long period of changeover working alongside his predecessor, Spofforth. In fact, Spofforth was urgently wanted in the new post to which he had been promoted, and Turner, within a few days of being told of his new appointment, found himself in sole command.

The organisation which he inherited was as illustrated in Figure 21.10.

South and Midlands Area manager vacancy. There were others, however; the plant had developed an intermittent defect which slowed production and meant that many deliveries were late. Several customers, notably Bucks Electrical Cables, were protesting vigorously. Furthermore, the sales director wanted two major reports. Each, Turner thought, would take at least a week of his time and severely tax his ability to produce new ideas and constructive proposals as well as his ability to write lucidly and elegantly. Yet he could not delay their production, or make anything less than a first-rate job of them, for fear of beginning his new appointment by disappointing the sales director.

DELEGATION OF DUTIES

Turner decided that he would ask Ferris to come to London for a few days. Apart from enabling him to obtain Ferris's views on the problems he faced, it would give him the opportunity to try to smooth out any resentment at his promotion.

Much to Turner's gratification, Ferris was extremely helpful. He made short work of Turner's reports. He was an abundant producer of ideas, and soon sketched out what seemed to Turner an eminently satisfactory set of proposals for both reports. He then offered to draft the reports for Turner, and dictated both during one afternoon. Turner, who normally made several laborious pencil drafts before attempting to finalise a report, was astonished at Ferris's facility. The drafts seemed to him quite perfect, and he signed them and sent them to the sales director.

Ferris next offered to go to 'pacify' Bucks Electrical Cables. Turner demurred saying it was his duty to deal personally with this problem, but Ferris insisted that Turner was too busy with managerial problems to spare the time. Turner was secretly relieved at not having to deal with these awkward customers. Ferris later telephoned to say that he had just taken three Bucks Electrical directors to lunch and they had all parted the best of friends.

Finally, Ferris put forward an idea about the area manager vacancy. He, Ferris, would take over the South and Midlands Area and his senior representative in the north, Palmer, could be promoted Northern and Scottish Area manager. Turner was strongly attracted by the prospect of having Ferris's services 'on tap' in London, and readily agreed to this proposal.

Ferris tackled his new job as South and Midlands Area manager with characteristic vigour and sales were soon moving upwards - indeed, the production people had to make Herculean efforts to squeeze out the additional product needed to cope with the increased orders. He found time, however, to give substantial personal help to Turner, and Turner came increasingly to rely on him. Whenever he had a problem to solve, a decision to make, or a report to write, he consulted Ferris. Normally it was Ferris who supplied the solution, suggested the decision to be adopted, or wrote the report.

Turner often felt guilty about the extent to which he relied on Ferris and sometimes apologised to him for 'leaning' so much on him. Ferris, however, had a soothing answer. This, he explained, was the normal process of delegation. It would be quite wrong for Turner to be continually involved in detail problems;

his function was to formulate the problems and leave his subordinates to solve them. Gradually, Turner came to accept the idea that his relationship with Ferris was no more than sound management;

he even began to boast to his manager friends about the 'delegation' that he practised and the troublefree life he led.

Questions

Consider the following questions:

(a) When an inadequate manager is supported by a more able subordinate, is it likely that the subordinate will become the effective manager of the unit? Is it desirable? If not, what steps (apart from replacement of the manager) could be taken to prevent it?

(b) Where are the boundaries between proper delegation of authority and abdication of responsibility? Was Turner, in fact, guilty of the latter?

(c) Where does willingness to accept responsibility end and personal 'empire building' begin? Was Ferris an 'empire builder'? If so, with what motives?

(d) How far can a theoretically undesirable system be justified on the ground that 'it works'?

(e) Should the sales director intervene in Turner's organisational and personal relations problems? If so, what should he do?

Step by Step Answer: