Refer to the BMW Company case. From the corresponding exercise in Chapter 3, review the design of

Question:

Refer to the BMW Company case. From the corresponding exercise in Chapter 3, review the design of a spreadsheet that will allow BMW management to estimate the cost of disposal a decade into the future (i.e., in 1999) as a percentage of net income.

a. What percentage is predicted for 1999, assuming there are no changes in trends and policies?

b. How does the percentage change as a function of BMW’s market share in 1999? (Consider a range from 5 percent to 8 percent.)

c. Construct a tornado chart for the analysis in (a). List the relevant parameters in descending order of their impact on the disposal cost.

d. Consider three scenarios, called Slow, Medium, and Fast, characterized by different landfill costs in 1999 (600, 1200, and 1800DM, respectively) and by different landfill percentages (60 percent, 50 percent, and 40 percent, respectively). For these scenarios, and assuming that incineration costs will run double landfill costs, construct a scenario table for BMW’s disposal cost in 1999 and the percentage of its net income that this figure represents.

THE BMW COMPANY

Late in the summer of 1989, the government of Germany was seriously considering an innovative policy affecting the treatment of scrapped vehicles. This policy would make auto manufacturers responsible for recycling and disposal of their vehicles at the end of their useful lives. Sometimes referred to as a ‘‘Producer Responsibility’’ policy, this regulation would obligate the manufacturers of automobiles to take back vehicles that were ready to be scrapped.

The auto takeback proposal was actually the first of several initiatives that would also affect the end-of-life (EOL) treatment of such other products as household appliances and consumer electronics. But in 1989, no other industry had faced anything like this new policy. Managers at BMW and other German automakers struggled to understand the implications for their own company. Perhaps the first exercise was to gauge the magnitude of the economic effect. Stated another way, management wanted to know what the cost of the new policy was likely to be, if BMW continued to do business as usual.

Background

A loose network of dismantlers and shredders managed most of the recycling and disposal of German vehicles, accounting for about 95 percent of EOL volume, or roughly 2.1 million vehicles per year. Dismantling was a labor-intensive process that removed auto parts, fluids, and materials that could be re-sold. The hulk that remained was sold to a shredder. Shredding was a capital-intensive business that separated the remaining materials into distinct streams. Ferrous metals were sold to steel producers, nonferrous metals were sold to specialized-metal companies, and the remaining material was typically sent to landfills or incinerators. The material headed for disposal was known as Automobile Shredder Residue (ASR) and consisted of plastic, rubber, foam, glass, and dirt. ASR was virtually impossible to separate into portions with any economic value, so shredders paid for its removal and disposal. As of 1989, the annual volume of ASR came to about 400,000 tons. On average, an automobile stayed in service for about 10 years.

Although dismantlers and shredders were unaffiliated, private businesses in 1989, it was conceivable that, under the new government policy, they would be taken over by the auto companies. Even if they remained independently owned businesses, the costs of dismantling and shredding would ultimately be borne by the auto companies, since the policy made them legally responsible for the waste.

Economics of disposal

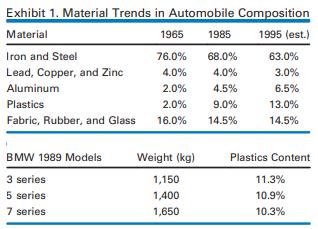

The costs in this system had been increasing and, in fact, were about to increase more quickly due to two major trends, one involving disposal costs and the other involving material composition. On the material side, automobiles were being designed with less metal each year and more plastics. In the 1960s, a typical car was made up of more than 80 percent metal, but the new models of 1990 were only about 75 percent metal. This meant that more of the vehicle was destined to end up as ASR. Averaged across the market, autos weighed an average of about 1,000 kg each. See Exhibit 1 for some representative figures.

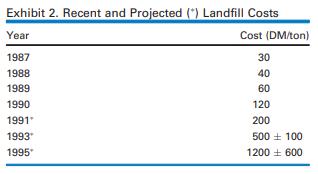

On the disposal side, a much more significant trend was in progress. As in most of Europe, landfill options were disappearing in Germany. In 1989, about half of the waste stream found its way to landfills, with 35 percent going to waste-to-energy incinerators, and the remaining 15 percent to recycling of some kind. But the number of landfills was declining, and it looked like this trend would continue, so that by 1999 landfill and incineration would handle approximately equal shares. The effects of supply and demand were visible in the costs of disposal at landfills. Exhibit 2 summarizes recent and projected costs.

Many landfills were of older designs, and public concern about their environmental risks had grown. Recent environmental regulations were beginning to restrict the materials that could be taken to landfills, and there was a good chance that ASR would be prohibited. Specially designed hazardous waste landfills were an alternative, but they tended to be three or four times as costly as the typical solid-waste landfill.

Meanwhile,the number of incinerators had grown from a handful in the early 1960s to nearly 50 by 1989, with prospects for another 25 or more in the coming decade. However, incinerators were expensive to build, and awareness of their environmental impacts was growing. In particular, the incineration of plastics had come under-special-scrutiny.The net effect was that incineration was about twice as costly as landfill disposal in 1989, and it was uncertain how the relative cost of incineration would evolve in the years to come.

Trends in the Market

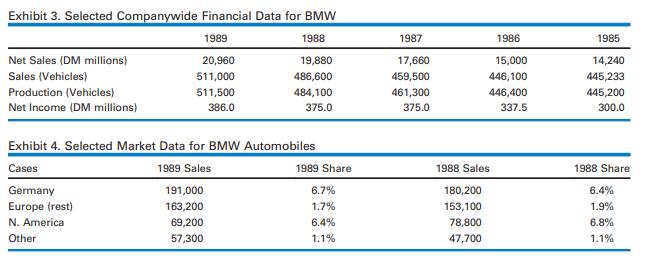

Prior to the 1980s, BMW cars were known for their reliability and quality. Only during the 80s did BMW acquire a reputation for performance and begin to compete in the high-end market. As a result, its domestic market share had risen from about 5.6 percent at the start of the decade to 6.7 percent in 1989. Some details of financial and market performance for BMW are summarized in Exhibits 3 and 4.

In 1989, BMW seemed poised to benefit from its successes over the previous several years, having consolidated its position in the marketplace. Long-range forecasts predicted that the economy would grow by about 2 percent in the coming decade, with inflation at no more than 4 percent. However, the proposed takeback policy raised questions about whether the company’s profitability could endure. Assuming that, in the new regulatory regime, automakers bear the cost of disposal, the task is to estimate how much of the firm’s net income will be devoted to EOL vehicles 10 years into the future.

Step by Step Answer:

Management Science The Art Of Modeling With Spreadsheets

ISBN: 1301

4th Edition

Authors: Stephen G. Powell, Kenneth R. Baker