On December 31, 1998, British Petroleum PLC (BP) bought Amoco Corp., the fourth-largest US oil company, for

Question:

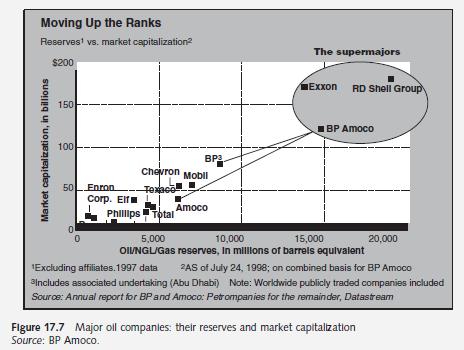

On December 31, 1998, British Petroleum PLC (BP) bought Amoco Corp., the fourth-largest US oil company, for \($52.41\) billion in stock, then the largest industrial merger in history. This deal surpassed the \($40.5\) billion dollar purchase of Chrysler Corp. by Germany’s Daimler-Benz AG, completed in November 1998. The combined company, named BP Amoco, would remain the world’s third-largest oil company, but the deal would make it a bigger rival to the number one, Royal Dutch/Shell, and the number two, Exxon Corp., in size and scope (see figure 17.7):

\($108\) billion in annual revenue, 14.8 billion barrels in oil and gas reserves, 1.9 million barrels of daily oil production, \($6.4\) billion in annual profit, \($132\) billion in market value, and 100,000

employees. Amoco shareholders received a 0.66 BP American depository receipt for each share of Amoco. This price represents a premium of about 15 percent to the value of Amoco before the merger. BP used the pooling-of-interest accounting treatment in acquiring Amoco instead of the purchase-of-asset accounting treatment.

“The potential for cost-cutting and improving efficiencies is enormous,” said analyst Fadel Gheit at Fahne-Stock & Co. “There will be no weakness in the new company, which will have the two top international players looking over their shoulders.”

By combining operations, BP Amoco contended that it would cut \($2\) billion in annual costs from its operations by the end of the year 2000, boost its annual pretax profits by a few hundred million dollars in the next 2 years, and reduce the cost of capital substantially. This combined company failed to increase its earnings in 1999, but the merger boosted shareholder value substantially through December 1999.

BP had already demonstrated that it knows how to hold down costs, most notably during a big reorganization that took place in the early 1990s, when it slashed its payroll deeply. Now, led by Chief Executive John Brown, BP was expected to apply some of the same discipline to Amoco, whose performance on the cost-cutting front had lagged. But, just as important, there was also the potential for substantial growth. The combined company’s revenues would enable it to finance more development itself, keep costs down, and help win more victories at auctions of oil reserves. Analysts stated that the assets of these two companies complimented each other. BP brought a huge worldwide exploration and production operation to the company, plus a strong European retail network. As for Amoco, it was the largest natural gas producer in North America and had a large US gasoline marketing network. Both companies had petrochemicals operations that would become among the largest in some areas. Both also operated in the niche area of solar energy and would pose a challenge to that market’s leader, Germany’s Siemens AG.

More specifically, BP Amoco Chairman John Brown said that beyond the projected \($2\) billion in savings, he expected additional savings and growth opportunities. He pointed to such areas as Azerbaijan, the oil-rich Central Asian nation where both companies are major players. Other synergies would include deeper-water exploration and production, where BP would bring its expertise to Amoco’s fields in the Gulf of Mexico. Similarly, the deal could combine Amoco’s lower development costs with BP’s cheaper exploration costs.

Since BP announced its proposed acquisition of Amoco in August 1998, a wave of merger activity has hit the oil industry. These more recent acquisitions include Exxon’s agreement to buy Mobile for \($75\) billion, BP Amoco’s proposed merger with Arco for \($25\) billion, the agreement by France’s Total SA to buy Belgium’s Petrofina SA for \($15\) billion, and proposed alliances among national oil companies of Brazil, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela. Why have all these oil mergers and alliances happened in recent years? First, the most successful companies, such as BP and Exxon, had already slashed costs. When costs have been cut to the bone, merger remains a route to higher profits. Second, advances in drilling and other oil technologies have enabled oil companies to discover previously untapped oil fields. In addition, these new technologies have allowed hundreds of players to produce ever larger amounts of petroleum at ever lower costs.

Case Questions 1 Explain how BP Amoco could cut \($2\) billion in costs and boost annual pretax profits by a few hundred million dollars for the first 2 years.

2 Explain how this merger could reduce its cost of capital substantially.

3 Why did BP treat its merger with Amoco as a pooling transaction rather than a purchase transaction?

4 Explain how the BP–Amoco merger could boost its shareholder wealth as reflected by its stock price. According to the case, the combined company did not earn more money after the merger, but its stock price increased. How do you explain this apparent conflict between earnings and stock price?

5 Briefly explain American depository receipts. The last closing price per share for Amoco stock was about \($52.\) What was the closing price of BP American depository receipts (ADRs)

on its last trading day?

6 Some websites, such as www.dbc.com and www.quicken.com, provide many pieces of information about publicly held companies for investors. Use several websites of your choice to compare some key financial statistics of BP Amoco with those of its major competitors.

Step by Step Answer:

Global Corporate Finance Text And Cases

ISBN: 9781405119900

6th Edition

Authors: Suk H. Kim, Seung H. Kim