Question

1. Compute New England Seafoods weighted average cost of capital. (Hint: the weighted average cost of capital is equal to = ()(1 - t) +

1. Compute New England Seafoods weighted average cost of capital. (Hint: the weighted average cost of capital is equal to = ()(1 - t) + , where and are the fractions of debt and equity in the capital structure, and are the respective costs of debt and equity, and t is the corporate tax rate.)

2. Consider the land acquisition for Stage 1. a. What cost, if any, should be attributed to the catfish project? b. Assuming that the currently owned site is used for this project, how should the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division obtain a site? What discount rate should be used in analyzing the option alternative?

3. Now think about the other cash flows associated with Stage 1. a. If Stage 1 is undertaken, what would the R&D cash flows be for 2017 through 2021? b. Should any R&D cash flow for 2013 be included in the Stage 1 analysis? Explain. c. Describe how salvage values are taxed. Use the building's salvage value to illustrate your answer. d. Complete the project's cash flow statement by filling in the blanks in Table 2.

4. Assume that the Stage I project is judged to be of average risk. What are its stand-alone NPV, IRR, MIRR, and payback?

5. Consider the Stage 2 expansion project. What are its stand alone NPV, IRR, MIRR, and payback as of December 31, 2019 (t = 6) under each demand scenario? What are today's (t = 0) NPVs? What is Stage 2's expected NPV, assuming there is a 70 percent probability that demand will be high during Stage 2, but a 30 percent chance that demand will be low? Again, assume that Stage 2 is an average-risk project. (Hint: Remember that acceptance of Stage 2 requires the firm to forego the Stage 1 net working capital recovery. This represents an opportunity cost to Stage 2 that is not reflected in the cash flows shown on the previous page.)

6. Now New England Seafood considers the combination of Stage 1 and Stage 2 projects. It estimates that there is an 80 percent chance that Stage 1 will meet all expectations and, 5 consequently, that Stage 2 will be undertaken. Using Figure 1 as a guide, construct a decision tree for the analysis and measure the expected NPV of New England Seafood's catfish project (a combination of Stages 1 and 2 projects)?

7. Use the decision-tree data to find the project's standard deviation and coefficient of variation of NPV. Suppose that New England Seafood's average project has a coefficient of variation of NPV in the range of 0.5 to 1.5. Would this catfish project be classified as a high-, average-, or low-risk project?

8. What is the risk-adjusted NPV of the overall catfish project based on your risk analysis in Q#7?

9. What would you recommend to New England Seafoods executive committee? Carefully justify your final conclusions.

10. Defend or criticize the firms current practice of risk assessment method of using the coefficient of variation of NPV and classifying projects into high-, average, or low-risk project (as stated in Q#7). No quantitative analysis is needed.

11. Your boss, the finance vice president, is concerned that the variable cost percentage used (60%) might be too low, and that variable costs might actually amount to 70 percent of dollar sales. If variable costs do amount to 70 or even 75 percent, how would this affect the NPV of Stage 1 and the NPV of the total project? Calculate the NPV of Stage 1 at several higher variable cost percentages. Use a 10 percent cost of capital.

12. The marketing vice president thinks the salvage value estimate included in the Year 2025 high-demand scenario cash flow is inaccurate, so she asked you to use $30,000,000 instead of $37,500,000. She also asks you to assume that there is only a 60 percent, chance that demand will be high during Stage 2 and a 40 percent chance that demand will be low. What would be the specific effect of these changes on the expected NPV of the total catfish project?

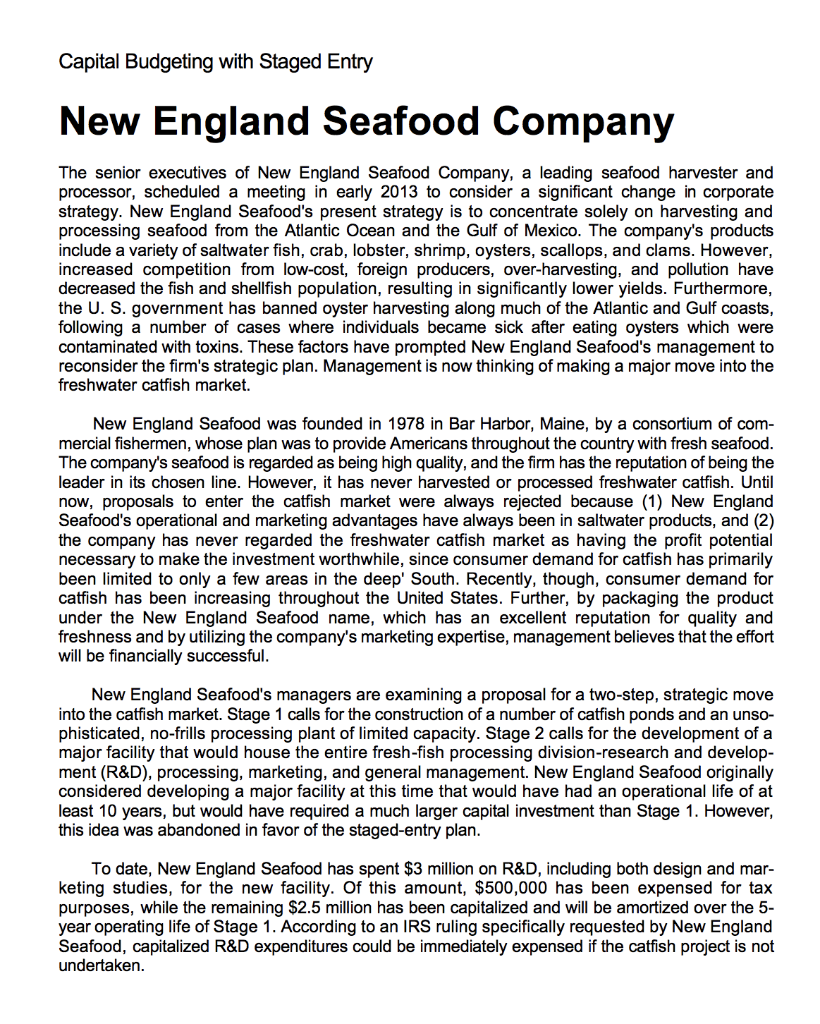

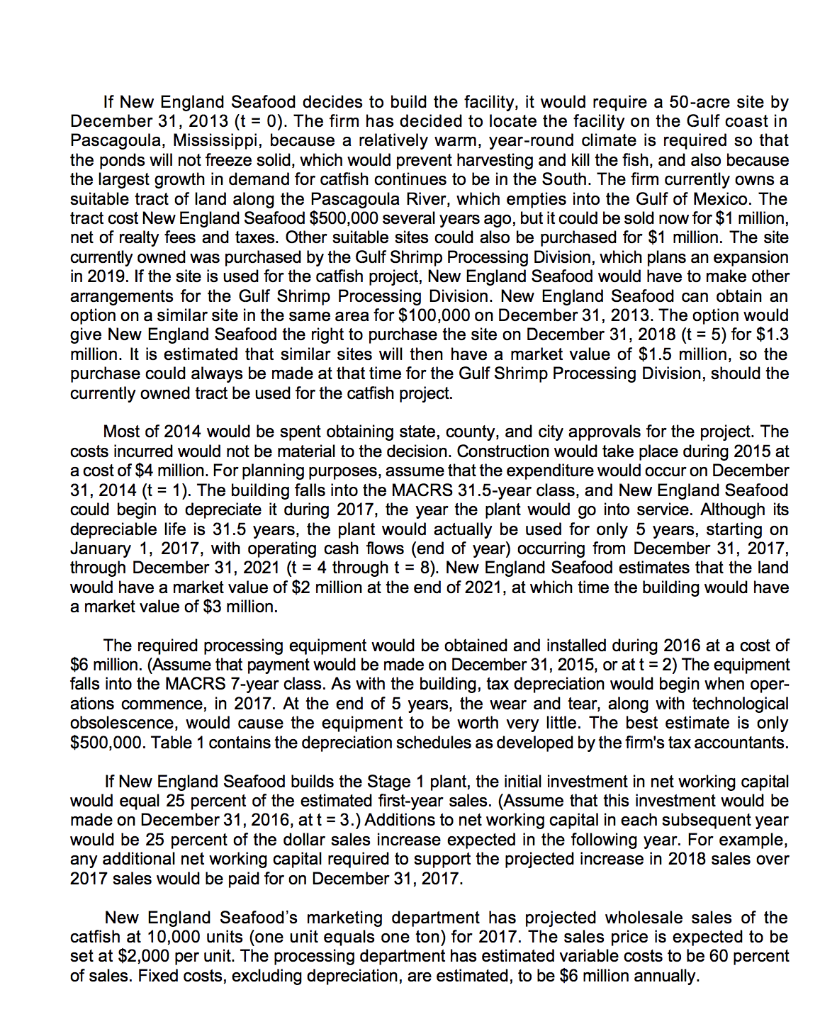

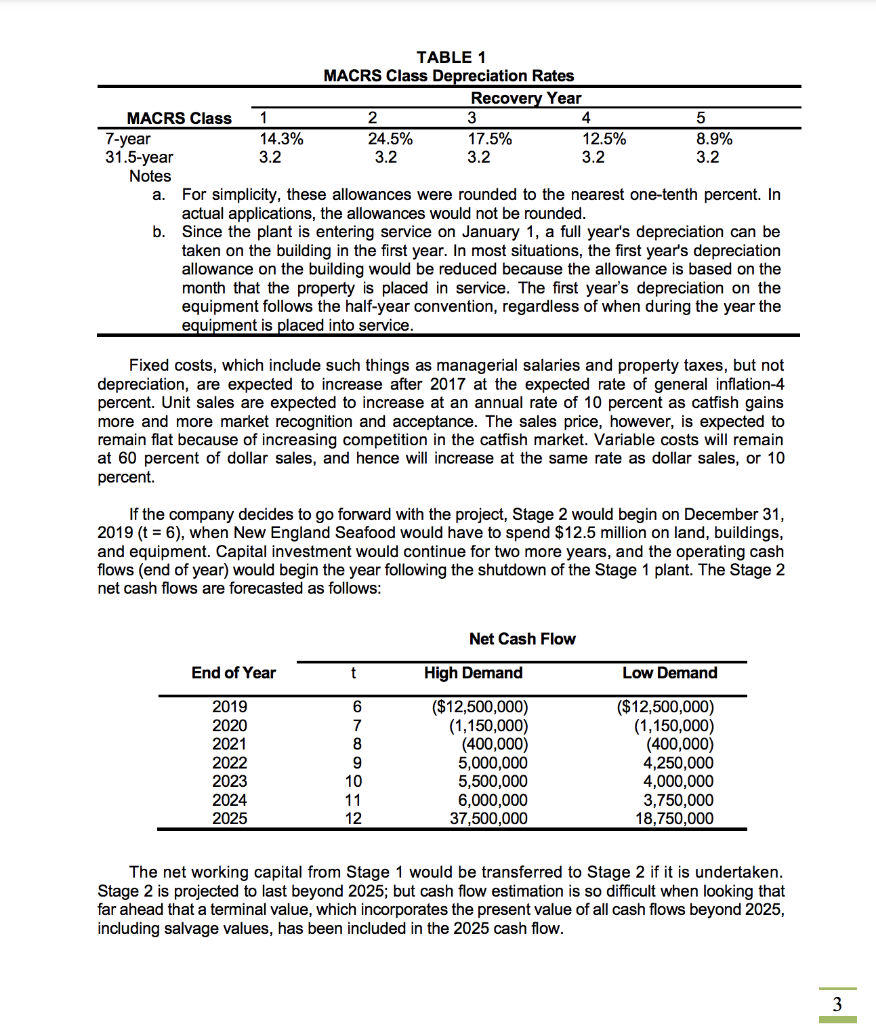

Capital Budgeting with Staged Entry New England Seafood Company The senior executives of New England Seafood Company, a leading seafood harvester and processor, scheduled a meeting in early 2013 to consider a significant change in corporate strategy. New England Seafood's present strategy is to concentrate solely on harvesting and processing seafood from the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. The company's products include a variety of saltwater fish, crab, lobster, shrimp, oysters, scallops, and clams. However, increased competition from low-cost, foreign producers, over-harvesting, and pollution have decreased the fish and shellfish population, resulting in significantly lower yields. Furthermore, the U. S. government has banned oyster harvesting along much of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, following a number of cases where individuals became sick after eating oysters which were contaminated with toxins. These factors have prompted New England Seafood's management to reconsider the firm's strategic plan. Management is now thinking of making a major move into the freshwater catfish market. New England Seafood was founded in 1978 in Bar Harbor, Maine, by a consortium of com- mercial fishermen, whose plan was to provide Americans throughout the country with fresh seafood. The company's seafood is regarded as being high quality, and the firm has the reputation of being the leader in its chosen line. However, it has never harvested or processed freshwater catfish. Until now, proposals to enter the catfish market were always rejected because (1) New England Seafood's operational and marketing advantages have always been in saltwater products, and (2) the company has never regarded the freshwater catfish market as having the profit potential necessary to make the investment worthwhile, since consumer demand for catfish has primarily been limited to only a few areas in the deep' South. Recently, though, consumer demand for catfish has been increasing throughout the United States. Further, by packaging the product under the New England Seafood name, which has an excellent reputation for quality and freshness and by utilizing the company's marketing expertise, management believes that the effort will be financially successful. New England Seafood's managers are examining a proposal for a two-step, strategic move into the catfish market. Stage 1 calls for the construction of a number of catfish ponds and an unso- phisticated, no-frills processing plant of limited capacity. Stage 2 calls for the development of a major facility that would house the entire fresh-fish processing division-research and develop- ment (R&D), processing, marketing, and general management. New England Seafood originally considered developing a major facility at this time that would have had an operational life of at least 10 years, but would have required a much larger capital investment than Stage 1. However, this idea was abandoned in favor of the staged-entry plan. To date, New England Seafood has spent $3 million on R&D, including both design and mar- keting studies, for the new facility. Of this amount, $500,000 has been expensed for tax purposes, while the remaining $2.5 million has been capitalized and will be amortized over the 5- year operating life of Stage 1. According to an IRS ruling specifically requested by New England Seafood, capitalized R&D expenditures could be immediately expensed if the catfish project is not undertaken. If New England Seafood decides to build the facility, it would require a 50-acre site by December 31, 2013 (t = 0). The firm has decided to locate the facility on the Gulf coast in Pascagoula, Mississippi, because a relatively warm, year-round climate is required so that the ponds will not freeze solid, which would prevent harvesting and kill the fish, and also because the largest growth in demand for catfish continues to be in the South. The firm currently owns a suitable tract of land along the Pascagoula River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The tract cost New England Seafood $500,000 several years ago, but it could be sold now for $1 million, net of realty fees and taxes. Other suitable sites could also be purchased for $1 million. The site currently owned was purchased by the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division, which plans an expansion in 2019. If the site is used for the catfish project, New England Seafood would have to make other arrangements for the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division. New England Seafood can obtain an option on a similar site in the same area for $100,000 on December 31, 2013. The option would give New England Seafood the right to purchase the site on December 31, 2018 (t = 5) for $1.3 million. It is estimated that similar sites will then have a market value of $1.5 million, so the purchase could always be made at that time for the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division, should the currently owned tract be used for the catfish project. Most of 2014 would be spent obtaining state, county, and city approvals for the project. The costs incurred would not be material to the decision. Construction would take place during 2015 at a cost of $4 million. For planning purposes, assume that the expenditure would occur on December 31, 2014 (t = 1). The building falls into the MACRS 31.5-year class, and New England Seafood could begin to depreciate it during 2017, the year the plant would go into service. Although its depreciable life is 31.5 years, the plant would actually be used for only 5 years, starting on January 1, 2017, with operating cash flows (end of year) occurring from December 31, 2017, through December 31, 2021 (t = 4 through t = 8). New England Seafood estimates that the land would have a market value of $2 million at the end of 2021, at which time the building would have a market value of $3 million. The required processing equipment would be obtained and installed during 2016 at a cost of $6 million. (Assume that payment would be made on December 31, 2015, or at t = 2) The equipment falls into the MACRS 7-year class. As with the building, tax depreciation would begin when oper- ations commence, in 2017. At the end of 5 years, the wear and tear, along with technological obsolescence, would cause the equipment to be worth very little. The best estimate is only $500,000. Table 1 contains the depreciation schedules as developed by the firm's tax accountants. If New England Seafood builds the Stage 1 plant, the initial investment in net working capital would equal 25 percent of the estimated first-year sales. (Assume that this investment would be made on December 31, 2016, at t = 3.) Additions to net working capital in each subsequent year would be 25 percent of the dollar sales increase expected in the following year. For example, any additional net working capital required to support the projected increase in 2018 sales over 2017 sales would be paid for on December 31, 2017. New England Seafood's marketing department has projected wholesale sales of the catfish at 10,000 units (one unit equals one ton) for 2017. The sales price is expected to be set at $2,000 per unit. The processing department has estimated variable costs to be 60 percent of sales. Fixed costs, excluding depreciation, are estimated, to be $6 million annually. TABLE 1 MACRS Class Depreciation Rates Recovery Year MACRS Class 1 2 3 4 5 7-year 14.3% 24.5% 17.5% 12.5% 8.9% 31.5-year 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 Notes a. For simplicity, these allowances were rounded to the nearest one-tenth percent. In actual applications, the allowances would not be rounded. b. Since the plant is entering service on January 1, a full year's depreciation can be taken on the building in the first year. In most situations, the first year's depreciation allowance on the building would be reduced because the allowance is based on the month that the property is placed in service. The first year's depreciation on the equipment follows the half-year convention, regardless of when during the year the equipment is placed into service. Fixed costs, which include such things as managerial salaries and property taxes, but not depreciation, are expected to increase after 2017 at the expected rate of general inflation-4 percent. Unit sales are expected to increase at an annual rate of 10 percent as catfish gains more and more market recognition and acceptance. The sales price, however, is expected to remain flat because of increasing competition in the catfish market. Variable costs will remain at 60 percent of dollar sales, and hence will increase at the same rate as dollar sales, or 10 percent. If the company decides to go forward with the project, Stage 2 would begin on December 31, 2019 (t = 6), when New England Seafood would have to spend $12.5 million on land, buildings, and equipment. Capital investment would continue for two more years, and the operating cash flows (end of year) would begin the year following the shutdown of the Stage 1 plant. The Stage 2 net cash flows are forecasted as follows: Net Cash Flow End of Year t High Demand Low Demand 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ($12,500,000) (1,150,000) (400,000) 5,000,000 5,500,000 6,000,000 37,500,000 ($12,500,000) (1,150,000) (400,000) 4,250,000 4,000,000 3,750,000 18,750,000 The net working capital from Stage 1 would be transferred to Stage 2 if it is undertaken. Stage 2 is projected to last beyond 2025; but cash flow estimation is so difficult when looking that far ahead that a terminal value, which incorporates the present value of all cash flows beyond 2025, including salvage values, has been included in the 2025 cash flow. 3 New England Seafood's current federal-plus-state tax rate is 40 percent, and this rate is projected to remain fairly constant into the future. The firm has its target debt ratio of 20 percent, and its cost of new debt is 10 percent. Its expected dividend next year, D1, is $2.00 per share with a future growth rate of 6 percent per year. The firm's current stock price, Po, is $40.00. New England Seafood uses its overall weighted average cost of capital in evaluating average risk projects, but adjusts this figure up or down by 3 percentage points for projects with substantially more or less risk than average. Assume that you are the financial analyst charged with analyzing the catfish project. Accord- ingly, it is your job to evaluate the project and to prepare a recommendation for New England Seafood's executive committee. In developing your recommendations, answer the following questions, which were posed by the financial vice president, your boss. Capital Budgeting with Staged Entry New England Seafood Company The senior executives of New England Seafood Company, a leading seafood harvester and processor, scheduled a meeting in early 2013 to consider a significant change in corporate strategy. New England Seafood's present strategy is to concentrate solely on harvesting and processing seafood from the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. The company's products include a variety of saltwater fish, crab, lobster, shrimp, oysters, scallops, and clams. However, increased competition from low-cost, foreign producers, over-harvesting, and pollution have decreased the fish and shellfish population, resulting in significantly lower yields. Furthermore, the U. S. government has banned oyster harvesting along much of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, following a number of cases where individuals became sick after eating oysters which were contaminated with toxins. These factors have prompted New England Seafood's management to reconsider the firm's strategic plan. Management is now thinking of making a major move into the freshwater catfish market. New England Seafood was founded in 1978 in Bar Harbor, Maine, by a consortium of com- mercial fishermen, whose plan was to provide Americans throughout the country with fresh seafood. The company's seafood is regarded as being high quality, and the firm has the reputation of being the leader in its chosen line. However, it has never harvested or processed freshwater catfish. Until now, proposals to enter the catfish market were always rejected because (1) New England Seafood's operational and marketing advantages have always been in saltwater products, and (2) the company has never regarded the freshwater catfish market as having the profit potential necessary to make the investment worthwhile, since consumer demand for catfish has primarily been limited to only a few areas in the deep' South. Recently, though, consumer demand for catfish has been increasing throughout the United States. Further, by packaging the product under the New England Seafood name, which has an excellent reputation for quality and freshness and by utilizing the company's marketing expertise, management believes that the effort will be financially successful. New England Seafood's managers are examining a proposal for a two-step, strategic move into the catfish market. Stage 1 calls for the construction of a number of catfish ponds and an unso- phisticated, no-frills processing plant of limited capacity. Stage 2 calls for the development of a major facility that would house the entire fresh-fish processing division-research and develop- ment (R&D), processing, marketing, and general management. New England Seafood originally considered developing a major facility at this time that would have had an operational life of at least 10 years, but would have required a much larger capital investment than Stage 1. However, this idea was abandoned in favor of the staged-entry plan. To date, New England Seafood has spent $3 million on R&D, including both design and mar- keting studies, for the new facility. Of this amount, $500,000 has been expensed for tax purposes, while the remaining $2.5 million has been capitalized and will be amortized over the 5- year operating life of Stage 1. According to an IRS ruling specifically requested by New England Seafood, capitalized R&D expenditures could be immediately expensed if the catfish project is not undertaken. If New England Seafood decides to build the facility, it would require a 50-acre site by December 31, 2013 (t = 0). The firm has decided to locate the facility on the Gulf coast in Pascagoula, Mississippi, because a relatively warm, year-round climate is required so that the ponds will not freeze solid, which would prevent harvesting and kill the fish, and also because the largest growth in demand for catfish continues to be in the South. The firm currently owns a suitable tract of land along the Pascagoula River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The tract cost New England Seafood $500,000 several years ago, but it could be sold now for $1 million, net of realty fees and taxes. Other suitable sites could also be purchased for $1 million. The site currently owned was purchased by the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division, which plans an expansion in 2019. If the site is used for the catfish project, New England Seafood would have to make other arrangements for the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division. New England Seafood can obtain an option on a similar site in the same area for $100,000 on December 31, 2013. The option would give New England Seafood the right to purchase the site on December 31, 2018 (t = 5) for $1.3 million. It is estimated that similar sites will then have a market value of $1.5 million, so the purchase could always be made at that time for the Gulf Shrimp Processing Division, should the currently owned tract be used for the catfish project. Most of 2014 would be spent obtaining state, county, and city approvals for the project. The costs incurred would not be material to the decision. Construction would take place during 2015 at a cost of $4 million. For planning purposes, assume that the expenditure would occur on December 31, 2014 (t = 1). The building falls into the MACRS 31.5-year class, and New England Seafood could begin to depreciate it during 2017, the year the plant would go into service. Although its depreciable life is 31.5 years, the plant would actually be used for only 5 years, starting on January 1, 2017, with operating cash flows (end of year) occurring from December 31, 2017, through December 31, 2021 (t = 4 through t = 8). New England Seafood estimates that the land would have a market value of $2 million at the end of 2021, at which time the building would have a market value of $3 million. The required processing equipment would be obtained and installed during 2016 at a cost of $6 million. (Assume that payment would be made on December 31, 2015, or at t = 2) The equipment falls into the MACRS 7-year class. As with the building, tax depreciation would begin when oper- ations commence, in 2017. At the end of 5 years, the wear and tear, along with technological obsolescence, would cause the equipment to be worth very little. The best estimate is only $500,000. Table 1 contains the depreciation schedules as developed by the firm's tax accountants. If New England Seafood builds the Stage 1 plant, the initial investment in net working capital would equal 25 percent of the estimated first-year sales. (Assume that this investment would be made on December 31, 2016, at t = 3.) Additions to net working capital in each subsequent year would be 25 percent of the dollar sales increase expected in the following year. For example, any additional net working capital required to support the projected increase in 2018 sales over 2017 sales would be paid for on December 31, 2017. New England Seafood's marketing department has projected wholesale sales of the catfish at 10,000 units (one unit equals one ton) for 2017. The sales price is expected to be set at $2,000 per unit. The processing department has estimated variable costs to be 60 percent of sales. Fixed costs, excluding depreciation, are estimated, to be $6 million annually. TABLE 1 MACRS Class Depreciation Rates Recovery Year MACRS Class 1 2 3 4 5 7-year 14.3% 24.5% 17.5% 12.5% 8.9% 31.5-year 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 Notes a. For simplicity, these allowances were rounded to the nearest one-tenth percent. In actual applications, the allowances would not be rounded. b. Since the plant is entering service on January 1, a full year's depreciation can be taken on the building in the first year. In most situations, the first year's depreciation allowance on the building would be reduced because the allowance is based on the month that the property is placed in service. The first year's depreciation on the equipment follows the half-year convention, regardless of when during the year the equipment is placed into service. Fixed costs, which include such things as managerial salaries and property taxes, but not depreciation, are expected to increase after 2017 at the expected rate of general inflation-4 percent. Unit sales are expected to increase at an annual rate of 10 percent as catfish gains more and more market recognition and acceptance. The sales price, however, is expected to remain flat because of increasing competition in the catfish market. Variable costs will remain at 60 percent of dollar sales, and hence will increase at the same rate as dollar sales, or 10 percent. If the company decides to go forward with the project, Stage 2 would begin on December 31, 2019 (t = 6), when New England Seafood would have to spend $12.5 million on land, buildings, and equipment. Capital investment would continue for two more years, and the operating cash flows (end of year) would begin the year following the shutdown of the Stage 1 plant. The Stage 2 net cash flows are forecasted as follows: Net Cash Flow End of Year t High Demand Low Demand 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ($12,500,000) (1,150,000) (400,000) 5,000,000 5,500,000 6,000,000 37,500,000 ($12,500,000) (1,150,000) (400,000) 4,250,000 4,000,000 3,750,000 18,750,000 The net working capital from Stage 1 would be transferred to Stage 2 if it is undertaken. Stage 2 is projected to last beyond 2025; but cash flow estimation is so difficult when looking that far ahead that a terminal value, which incorporates the present value of all cash flows beyond 2025, including salvage values, has been included in the 2025 cash flow. 3 New England Seafood's current federal-plus-state tax rate is 40 percent, and this rate is projected to remain fairly constant into the future. The firm has its target debt ratio of 20 percent, and its cost of new debt is 10 percent. Its expected dividend next year, D1, is $2.00 per share with a future growth rate of 6 percent per year. The firm's current stock price, Po, is $40.00. New England Seafood uses its overall weighted average cost of capital in evaluating average risk projects, but adjusts this figure up or down by 3 percentage points for projects with substantially more or less risk than average. Assume that you are the financial analyst charged with analyzing the catfish project. Accord- ingly, it is your job to evaluate the project and to prepare a recommendation for New England Seafood's executive committee. In developing your recommendations, answer the following questions, which were posed by the financial vice president, your bossStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started