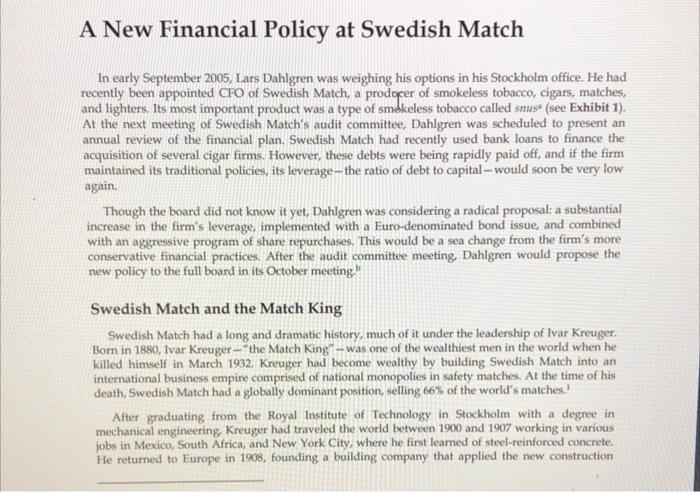

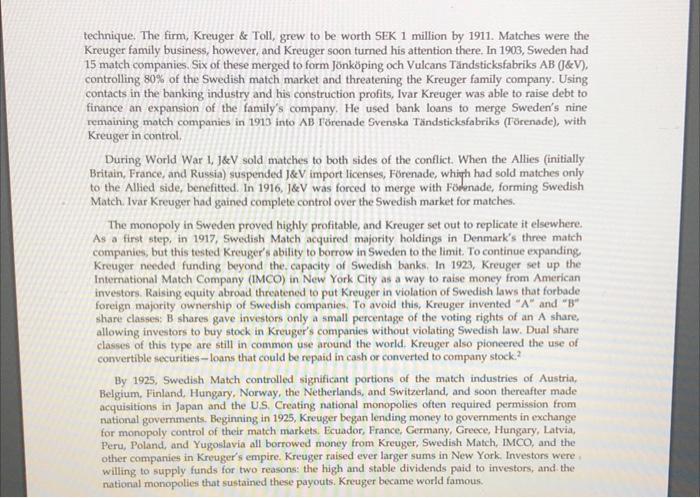

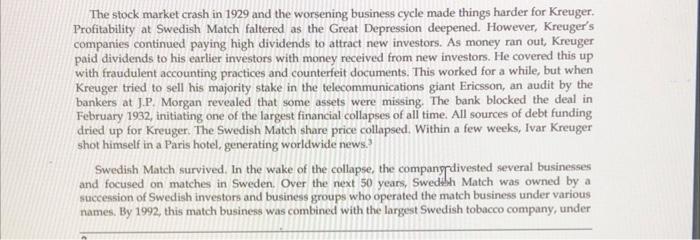

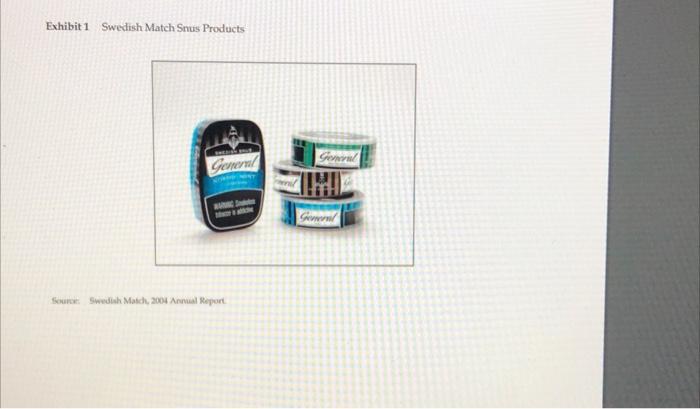

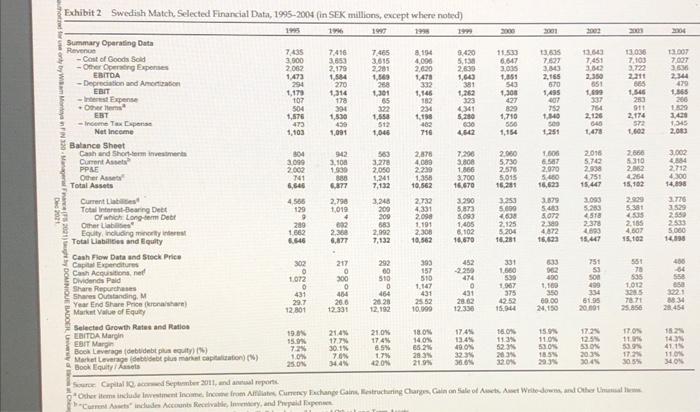

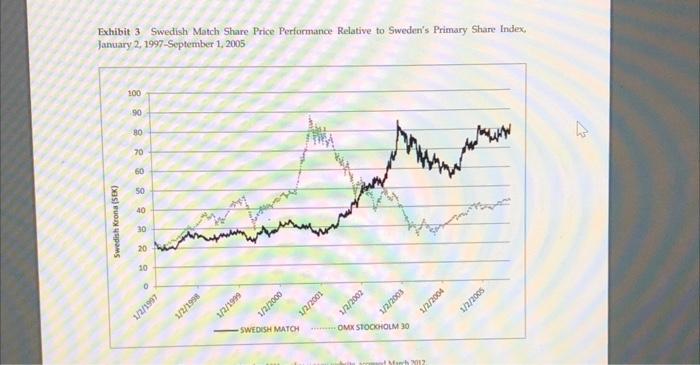

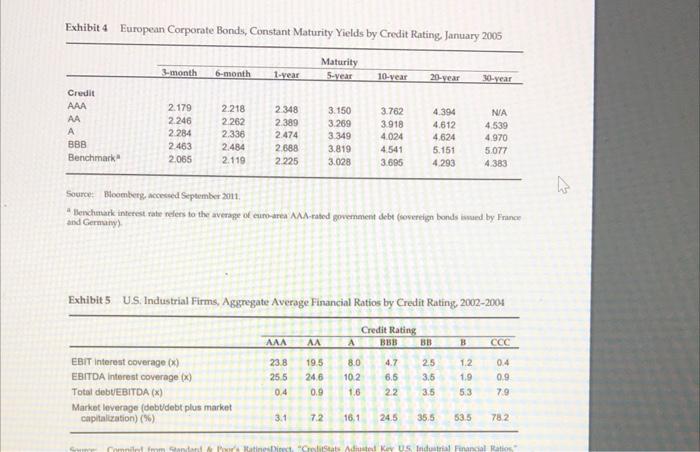

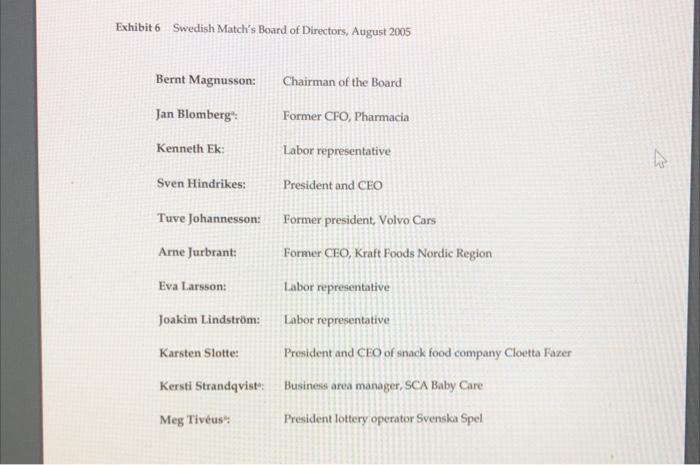

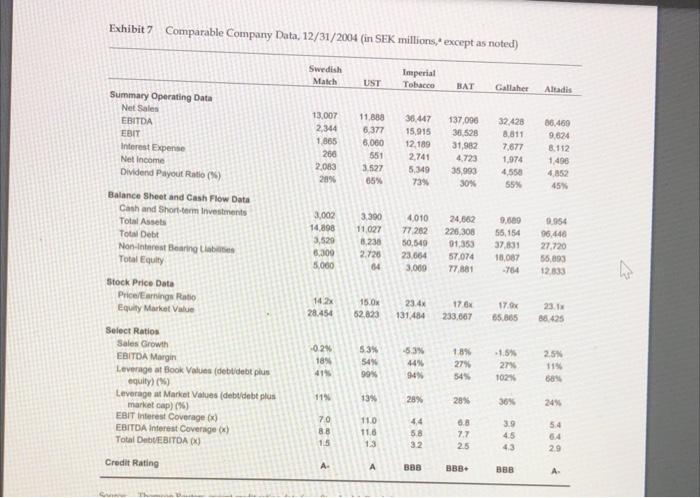

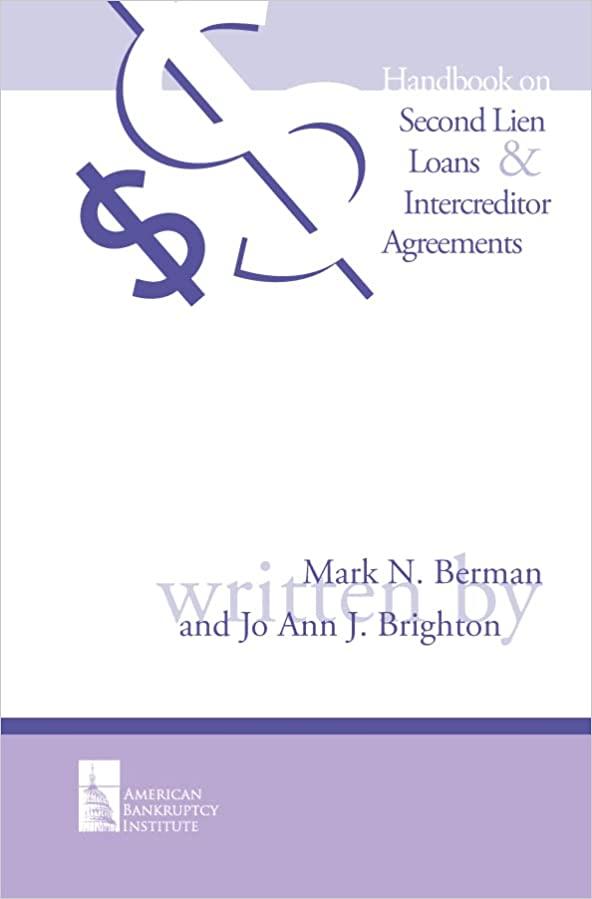

Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called smus (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage-the ratio of debt to capital - would soon be very low again. Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposal a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Euro-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices. After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting. Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger. Born in 1880, Ivar Kreuger-"the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete. He returned to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction technique. The firm, Kreuger & Toll, grew to be worth SEK 1 million by 1911. Matches were the Kreuger family business, however, and Kreuger soon turned his attention there. In 1903, Sweden had 15 match companies. Six of these merged to form Jnkping och Vulcans Tndsticksfabriks AB (J&V), controlling 80% of the Swedish match market and threatening the Kreuger family company. Using contacts in the banking industry and his construction profits, Ivar Kreuger was able to raise debt to finance an expansion of the family's company. He used bank loans to merge Sweden's nine remaining match companies in 1913 into AB I'Grenade Svenska Tndsticksfabriks (Teenade), with Kreuger in control During World War 1, J&V sold matches to both sides of the conflict. When the Allies (initially Britain, France, and Russia) suspended J&V import licenses, Frenade, which had sold matches only to the Allied side, benefitted. In 1916, J&V was forced to merge with Flnade, forming Swedish Match Ivar Kreuger had gained complete control over the Swedish market for matches. The monopoly in Sweden proved highly profitable, and Kreuger set out to replicate it elsewhere. As a first step, in 1917, Swedish Match acquired majority holdings in Denmark's three match companies, but this tested Kreuger's ability to borrow in Sweden to the limit. To continue expanding Kreuger needed funding beyond the capacity of Swedish banks. In 1923, Kreuger set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York City as a way to raise money from American investors. Raising equity abroad threatened to put Kreuger in violation of Swedish laws that forbade foreign majority ownership of Swedish companies. To avoid this, Kreuger invented "A" and "B" share classes: B shares gave investors only a small percentage of the voting rights of an A share, allowing investors to buy stock in Kreuger's companies without violating Swedish law. Dual share classes of this type are still in common use around the world. Kreuger also pioneered the use of convertible securities-loans that could be repaid in cash or converted to company stock? By 1925, Swedish Match controlled significant portions of the match industries of Austria, Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Norway, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, and soon thereafter made acquisitions in Japan and the U.S. Creating national monopolies often required permission from national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger began lending money to governments in exchange for monopoly control of their match markets. Ecuador, France, Germany Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons: the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger. Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's companies continued paying high dividends to attract new investors. As money ran out, Kreuger paid dividends to his earlier investors with money received from new investors. He covered this up with fraudulent accounting practices and counterfeit documents. This worked for a while, but when Kreuger tried to sell his majority stake in the telecommunications giant Ericsson, an audit by the bankers at J.P. Morgan revealed that some assets were missing. The bank blocked the deal in February 1932, initiating one of the largest financial collapses of all time. All sources of debt funding dried up for Kreuger. The Swedish Match share price collapsed. Within a few weeks, Ivar Kreuger shot himself in a Paris hotel, generating worldwide news. Swedish Match survived. In the wake of the collapse, the companypdivested several businesses and focused on matches in Sweden. Over the next 50 years, Swedibh Match was owned by a succession of Swedish investors and business groups who operated the match business under various names. By 1992, this match business was combined with the largest Swedish tobacco company, under the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth, (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) I Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States, Snus had been banned in the Eu since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market. In Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Gteborgs Rap, Ettan, and Catch held a dominant market position. Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking. Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes. Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002. With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market. wat for smokelecs tobacco products with over 900 The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the US, in 2004. In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhorn and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the U.S. market included Grizzly, Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuff Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by US Smokeless Tobacco Company. Demand for snus and moist snuff was growing in the US. in 2004, as more people chose smokeless tobacco over cigarettes. Red Man, Swedish Match's chewing tobacco brand, was sold only in the United States and was the market leader, with a 43% market share in 2004, and Swedish Match was hoping for further growth of snus products.10 After smokeless tobacco, Swedish Match's most important single product was cigars, which comprised 24% of sales and 59% of operating income in 2004. Swedish Match was the world's number two cigar manufacturer, and the global leader in the premium segment of the US market." Swedish Match produced both machine-made and premium cigars. Premium cigars, which were made by hand, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean, accounted for 24% of Swedish Match's sales volume, and 20% of operating income in 2004. The market for machine-made cigars in the United States and Western Europe was estimated at about 13 billion cigars per year, of which Swedish Match supplied about 7%. Flavored cigars were considered the segment with the largest growth potential.2 Chewing tobacco, a stagnating product category sold mostly in the US, generated 8% of sales and 13% of operating income in 2004. In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in US sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained 16% market share in the US and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong." Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income. Overall, Scandinavia, the US, and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P" (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings) A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting the board would decide on a Binancial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28% where it was expected to remain. There were other advantages to higher leverage. Some viewed excess cash or debt capacity negatively, seeing them as potentially leading to waste and inefficiency. the art of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors wme large owners earlier that year, Further, the act of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors seemed to agree with a more aggressive policy. In a survey of some large owners earlier that year, several had expressed support for increased repurchases. A Citibank analyst reported, "we expect the company to buy back SEK 9-12 billion in shares by the end of 2007." Dahlgren also felt that the lack of explicit financial targets created unnecessary uncertainty. Finally, looking to international peers (see Exhibit 7 for selected financials), Dahlgren noticed that many of them maintained high leverage. In contrast, Dahlgren also ticked off the disadvantages of debt in his head. Net income would be lower, because some of the firm's cash flows would go to interest payments. Raising new debt might also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years. Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 15 billion Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK BO in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren claborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity... traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks" Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher loverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical downturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue. a Exhibiti Swedish Match Snus Products General General Sem Sour Swedish March, 2004 Annual Report Exhibit 2 Swedish Match, Selected Financial Data, 1995-2004 in SEK millions, except where noted) 200 2004 38 2.600 EBITDA 7.007 360 2.344 470 10 1.5 1. 2:30 270 13.036 7.103 3.722 2211 06 1.546 280 911 670 1.14 1.300 OP 1.578 10 2174 200 1200 1400 1545 2,083 512 so 572 25 Sre 5.015 by Winter 20. (2001) DOMINIQUE BLADDER 2.600 5310 2.02 4264 15,102 2.000 5.381 4 3.24 3.002 44 2712 4300 14.898 2.770 3529 2.550 2533 5.000 14.00 1 1998 3001 100 Summary Operating Data Reven -Cont of Goods Sold 7,435 7416 7,465 8.154 11.30 13543 3.500 -Ohrer Expenses 3615 4.000 6.647 7.627 2002 2.179 2301 7451 3.035 3. 3. Depreciation and Action 2011 1.560 1.478 2.185 294 332 EBIT 503 1,170 314 651 - Expense 1.301 1 ASS 107 170 5 1.000 -Omer 65 182 427 504 ENT 304 222 337 234 809 1530 150 754 - Income Tax pense 1.550 1.710 1,340 2.125 470 450 102 Net Income 550 1,103 1,001 1,046 716 640 Balance Sheet Cash and Short-term este 304 942 2878 Current Ass 2.060 1.000 2016 3099 3.100 PPLE 3.278 4080 5,730 6.57 2002 1900 Other As 2.050 2.230 2.570 2970 2.000 741 380 1241 1,358 Total Assets 5.000 4751 6.646 877 7,132 10,562 16.623 15.447 Current 2,790 3,250 3.879 Total Interest-Bearing Dett 3.000 120 1,019 200 4331 of which Long-term Date 5.000 5.400 5.283 2.000 Other Lab 4.600 3072 4510 289 012 1.191 2.125 2370 Equity, including more 1 882 22 2,992 2.300 5.204 4872 100 Total Liabilities and Equity 6.646 4.877 7.132 10,562 16.281 16,023 15.47 Cash Flow Data and Stock Price Sap Expenditures 302 217 292 393 633 750 Cash Action, net 0 O 00 157 1.660 53 Dividends Paid 1.072 300 510 400 SOM Share Repurchases 0 0 1067 1,100 Share Outstanding, M 464 464 431 375 350 354 Year End Share Prion kronalar 29.7 206 20.28 2552 42.52 00.00 61.95 Market value of Equity 12.801 12.331 12.192 10.000 15.04 21.150 2001 Selected Growth Rates and Ration EBITDA Margin 19. 21.4 21.04 18 ON 16.04 15 17.2 ESIT Margir 15. 17. 17:45 14.0 113 11.09 12.5 Book Coverage (debidebit plus equity) IN) 30.1% 6.5 852 523 530 SON 10% 70% 17 283 203 1855 203 Book Equity Ass 250 344 420 2194 3209 22:30:45 So Capital 2011, and anal por Other endement in Incoram AmilCurrency Exchange Gains estructuring Clures in one of A Wi-down, and the Un Current indudes Accounts Review, and opene 12 200 553 2.00 2.18 4607 15.102 331 551 78 $35 1012 430 -64 550 510 431 787 25.856 3221 8834 28454 09 11. ) (*) 172 305 14 4115 110 34 ON Exhibit 3 Swedish Match Share Price Performance Relative to Sweden's Primary Share Index, January 2, 1997-September 1, 2005 100 90 80 8 8 8 70 60 50 40 Swedish Krona (SEK) 30 20 10 o 1/2/1997 666/ 1/2/2000 1/2/2001 1/2/2003 1/2/2004 1/2/2005 1/2/2002 SWEDISH MATCH OMX STOCKHOLM 30 2 Exhibit 4 European Corporate Bonds, Constant Maturity Yields by Credit Rating January 2005 3-month 6-month Maturity 5-year 1.vear 10-vear 20-year 30-year Credit AA A BBB Benchmark 2.179 2246 2284 2.463 2065 2.218 2262 2336 2.484 2.119 2348 2.389 2.474 2688 2.225 3.150 3.269 3349 3.819 3.028 3.762 3.918 4,024 4.541 3.695 4.394 4.612 4 624 5.151 4.293 NA 4539 4.970 5.077 4.383 Source Bloomberg, accessed September 2011 Wenchack interest rate refers to the average of euro-area MA-rated government chebt (fevereign bonds ward by France and Germany Exhibit 5 US. Industrial Firms, Aggregate Average Financial Ratios by Credit Rating 2002-2004 Credit Rating A BB BE AAA AA B EBIT interest coverage (00 EBITDA Interest coverage (x) Total debUEBITDA (X) Market leverage (debt/debt plus market capitalization (96) 23.8 25.5 0.4 195 24.6 0.9 8.0 102 1.6 4.7 6.5 22 25 3,5 3.5 12 1.9 5.3 0.4 0.9 79 3.1 72 16.1 24.5 35.5 535 782 Cantineid. Great Adil Key US Industrial Financial Ratios Exhibit 6 Swedish Match's Board of Directors, August 2005 Bernt Magnusson: Chairman of the Board Jan Blomberg Former CFO, Pharmacia Kenneth Ek: Labor representative w Sven Hindrikes: President and CEO Tuve Johannesson: Former president, Volvo Cars Arne Jurbrant: Former CEO, Kraft Foods Nordic Region Labor representative Eva Larsson: Joakim Lindstrm: Labor representative Karsten Slotte: President and CEO of snack food company cloetta Fazer Kersti Strandqvist Business area manager, SCA Baby Care Meg Tivus": President lottery operator Svenska Spel Exhibit 7 Comparable Company Data, 12/31/2004 (in SEK millions, except as noted) Swedish Match UST Imperial Tobacco BAT Galler Altadis 13.007 2,344 1 865 266 2,083 20% Summary Operating Data Net Sales EBITDA EBIT Interest Expense Net Income Dividend Payout Ratio ( Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Data Cash and Short-term Investments Total Assets Total Debt Non interest Bearing Total Equity 11.888 6 377 6,060 551 3.527 65% 35,447 15.915 12.180 2,741 5,349 73% 137.000 36 528 31,982 4.723 35.993 30% 32,428 8.811 7,677 1,974 4550 55% 86,460 9.624 8.112 1490 4.852 45 3.300 11.027 3,002 14.898 3.520 6.300 5.000 8.238 4,010 77262 50.540 23.064 3.000 24,662 226,308 01.353 57,074 77.881 9.689 55,154 37.831 18087 -764 9.954 96.446 27.720 55093 12.833 2.726 64 142 28.454 15.0x 52,823 23.4 131.484 17 x 233,667 17. 65.865 23.1 38.425 Stock Price Data Price/Earnings Ratio Equity Market Value Select Ratios Sales Growth EBITDA Margin Leverage at Book Values (debudebt plus equity) () Leverage at Market Values (debt debt plus market cap) (%) EBIT interest Coverage EBITDA Interest Coverage ) Total DEBITDA) -0.2% 18% 415 53% 54% 99% -6.3% 44% 94 18% 279 545 -15% 27% 1024 2.5 115 68% 11% 13% 28% 28% 36% 24% 70 88 1.5 11.0 110 13 44 5.8 32 6.8 7.7 2.5 39 4.5 5.4 0.4 29 Credit Rating A. BBB BBB BBB A Question 3 (10 Points) Dahlgren believes that if Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction it would likely receive a credit rating of BBB by S&P. Do you share Dahlgren's view or not? Explain your answer. (Hint: To answer this question, I would like you to calculate some of the metrics in Exhibit 5 for Swedish Match under the new proposed financial policy.) A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called smus (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage-the ratio of debt to capital - would soon be very low again. Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposal a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Euro-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices. After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting. Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger. Born in 1880, Ivar Kreuger-"the Match King" - was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches! After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete. He returned to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction technique. The firm, Kreuger & Toll, grew to be worth SEK 1 million by 1911. Matches were the Kreuger family business, however, and Kreuger soon turned his attention there. In 1903, Sweden had 15 match companies. Six of these merged to form Jnkping och Vulcans Tndsticksfabriks AB (J&V), controlling 80% of the Swedish match market and threatening the Kreuger family company. Using contacts in the banking industry and his construction profits, Ivar Kreuger was able to raise debt to finance an expansion of the family's company. He used bank loans to merge Sweden's nine remaining match companies in 1913 into AB I'Grenade Svenska Tndsticksfabriks (Teenade), with Kreuger in control During World War 1, J&V sold matches to both sides of the conflict. When the Allies (initially Britain, France, and Russia) suspended J&V import licenses, Frenade, which had sold matches only to the Allied side, benefitted. In 1916, J&V was forced to merge with Flnade, forming Swedish Match Ivar Kreuger had gained complete control over the Swedish market for matches. The monopoly in Sweden proved highly profitable, and Kreuger set out to replicate it elsewhere. As a first step, in 1917, Swedish Match acquired majority holdings in Denmark's three match companies, but this tested Kreuger's ability to borrow in Sweden to the limit. To continue expanding Kreuger needed funding beyond the capacity of Swedish banks. In 1923, Kreuger set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York City as a way to raise money from American investors. Raising equity abroad threatened to put Kreuger in violation of Swedish laws that forbade foreign majority ownership of Swedish companies. To avoid this, Kreuger invented "A" and "B" share classes: B shares gave investors only a small percentage of the voting rights of an A share, allowing investors to buy stock in Kreuger's companies without violating Swedish law. Dual share classes of this type are still in common use around the world. Kreuger also pioneered the use of convertible securities-loans that could be repaid in cash or converted to company stock? By 1925, Swedish Match controlled significant portions of the match industries of Austria, Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Norway, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, and soon thereafter made acquisitions in Japan and the U.S. Creating national monopolies often required permission from national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger began lending money to governments in exchange for monopoly control of their match markets. Ecuador, France, Germany Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons: the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger. Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's companies continued paying high dividends to attract new investors. As money ran out, Kreuger paid dividends to his earlier investors with money received from new investors. He covered this up with fraudulent accounting practices and counterfeit documents. This worked for a while, but when Kreuger tried to sell his majority stake in the telecommunications giant Ericsson, an audit by the bankers at J.P. Morgan revealed that some assets were missing. The bank blocked the deal in February 1932, initiating one of the largest financial collapses of all time. All sources of debt funding dried up for Kreuger. The Swedish Match share price collapsed. Within a few weeks, Ivar Kreuger shot himself in a Paris hotel, generating worldwide news. Swedish Match survived. In the wake of the collapse, the companypdivested several businesses and focused on matches in Sweden. Over the next 50 years, Swedibh Match was owned by a succession of Swedish investors and business groups who operated the match business under various names. By 1992, this match business was combined with the largest Swedish tobacco company, under the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth, (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) I Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States, Snus had been banned in the Eu since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market. In Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Gteborgs Rap, Ettan, and Catch held a dominant market position. Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking. Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes. Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002. With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market. wat for smokelecs tobacco products with over 900 The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the US, in 2004. In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhorn and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the U.S. market included Grizzly, Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuff Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by US Smokeless Tobacco Company. Demand for snus and moist snuff was growing in the US. in 2004, as more people chose smokeless tobacco over cigarettes. Red Man, Swedish Match's chewing tobacco brand, was sold only in the United States and was the market leader, with a 43% market share in 2004, and Swedish Match was hoping for further growth of snus products.10 After smokeless tobacco, Swedish Match's most important single product was cigars, which comprised 24% of sales and 59% of operating income in 2004. Swedish Match was the world's number two cigar manufacturer, and the global leader in the premium segment of the US market." Swedish Match produced both machine-made and premium cigars. Premium cigars, which were made by hand, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean, accounted for 24% of Swedish Match's sales volume, and 20% of operating income in 2004. The market for machine-made cigars in the United States and Western Europe was estimated at about 13 billion cigars per year, of which Swedish Match supplied about 7%. Flavored cigars were considered the segment with the largest growth potential.2 Chewing tobacco, a stagnating product category sold mostly in the US, generated 8% of sales and 13% of operating income in 2004. In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in US sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained 16% market share in the US and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong." Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income. Overall, Scandinavia, the US, and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P" (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings) A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting the board would decide on a Binancial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28% where it was expected to remain. There were other advantages to higher leverage. Some viewed excess cash or debt capacity negatively, seeing them as potentially leading to waste and inefficiency. the art of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors wme large owners earlier that year, Further, the act of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors seemed to agree with a more aggressive policy. In a survey of some large owners earlier that year, several had expressed support for increased repurchases. A Citibank analyst reported, "we expect the company to buy back SEK 9-12 billion in shares by the end of 2007." Dahlgren also felt that the lack of explicit financial targets created unnecessary uncertainty. Finally, looking to international peers (see Exhibit 7 for selected financials), Dahlgren noticed that many of them maintained high leverage. In contrast, Dahlgren also ticked off the disadvantages of debt in his head. Net income would be lower, because some of the firm's cash flows would go to interest payments. Raising new debt might also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years. Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 15 billion Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK BO in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren claborated: "Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity... traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks" Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher loverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical downturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue. a Exhibiti Swedish Match Snus Products General General Sem Sour Swedish March, 2004 Annual Report Exhibit 2 Swedish Match, Selected Financial Data, 1995-2004 in SEK millions, except where noted) 200 2004 38 2.600 EBITDA 7.007 360 2.344 470 10 1.5 1. 2:30 270 13.036 7.103 3.722 2211 06 1.546 280 911 670 1.14 1.300 OP 1.578 10 2174 200 1200 1400 1545 2,083 512 so 572 25 Sre 5.015 by Winter 20. (2001) DOMINIQUE BLADDER 2.600 5310 2.02 4264 15,102 2.000 5.381 4 3.24 3.002 44 2712 4300 14.898 2.770 3529 2.550 2533 5.000 14.00 1 1998 3001 100 Summary Operating Data Reven -Cont of Goods Sold 7,435 7416 7,465 8.154 11.30 13543 3.500 -Ohrer Expenses 3615 4.000 6.647 7.627 2002 2.179 2301 7451 3.035 3. 3. Depreciation and Action 2011 1.560 1.478 2.185 294 332 EBIT 503 1,170 314 651 - Expense 1.301 1 ASS 107 170 5 1.000 -Omer 65 182 427 504 ENT 304 222 337 234 809 1530 150 754 - Income Tax pense 1.550 1.710 1,340 2.125 470 450 102 Net Income 550 1,103 1,001 1,046 716 640 Balance Sheet Cash and Short-term este 304 942 2878 Current Ass 2.060 1.000 2016 3099 3.100 PPLE 3.278 4080 5,730 6.57 2002 1900 Other As 2.050 2.230 2.570 2970 2.000 741 380 1241 1,358 Total Assets 5.000 4751 6.646 877 7,132 10,562 16.623 15.447 Current 2,790 3,250 3.879 Total Interest-Bearing Dett 3.000 120 1,019 200 4331 of which Long-term Date 5.000 5.400 5.283 2.000 Other Lab 4.600 3072 4510 289 012 1.191 2.125 2370 Equity, including more 1 882 22 2,992 2.300 5.204 4872 100 Total Liabilities and Equity 6.646 4.877 7.132 10,562 16.281 16,023 15.47 Cash Flow Data and Stock Price Sap Expenditures 302 217 292 393 633 750 Cash Action, net 0 O 00 157 1.660 53 Dividends Paid 1.072 300 510 400 SOM Share Repurchases 0 0 1067 1,100 Share Outstanding, M 464 464 431 375 350 354 Year End Share Prion kronalar 29.7 206 20.28 2552 42.52 00.00 61.95 Market value of Equity 12.801 12.331 12.192 10.000 15.04 21.150 2001 Selected Growth Rates and Ration EBITDA Margin 19. 21.4 21.04 18 ON 16.04 15 17.2 ESIT Margir 15. 17. 17:45 14.0 113 11.09 12.5 Book Coverage (debidebit plus equity) IN) 30.1% 6.5 852 523 530 SON 10% 70% 17 283 203 1855 203 Book Equity Ass 250 344 420 2194 3209 22:30:45 So Capital 2011, and anal por Other endement in Incoram AmilCurrency Exchange Gains estructuring Clures in one of A Wi-down, and the Un Current indudes Accounts Review, and opene 12 200 553 2.00 2.18 4607 15.102 331 551 78 $35 1012 430 -64 550 510 431 787 25.856 3221 8834 28454 09 11. ) (*) 172 305 14 4115 110 34 ON Exhibit 3 Swedish Match Share Price Performance Relative to Sweden's Primary Share Index, January 2, 1997-September 1, 2005 100 90 80 8 8 8 70 60 50 40 Swedish Krona (SEK) 30 20 10 o 1/2/1997 666/ 1/2/2000 1/2/2001 1/2/2003 1/2/2004 1/2/2005 1/2/2002 SWEDISH MATCH OMX STOCKHOLM 30 2 Exhibit 4 European Corporate Bonds, Constant Maturity Yields by Credit Rating January 2005 3-month 6-month Maturity 5-year 1.vear 10-vear 20-year 30-year Credit AA A BBB Benchmark 2.179 2246 2284 2.463 2065 2.218 2262 2336 2.484 2.119 2348 2.389 2.474 2688 2.225 3.150 3.269 3349 3.819 3.028 3.762 3.918 4,024 4.541 3.695 4.394 4.612 4 624 5.151 4.293 NA 4539 4.970 5.077 4.383 Source Bloomberg, accessed September 2011 Wenchack interest rate refers to the average of euro-area MA-rated government chebt (fevereign bonds ward by France and Germany Exhibit 5 US. Industrial Firms, Aggregate Average Financial Ratios by Credit Rating 2002-2004 Credit Rating A BB BE AAA AA B EBIT interest coverage (00 EBITDA Interest coverage (x) Total debUEBITDA (X) Market leverage (debt/debt plus market capitalization (96) 23.8 25.5 0.4 195 24.6 0.9 8.0 102 1.6 4.7 6.5 22 25 3,5 3.5 12 1.9 5.3 0.4 0.9 79 3.1 72 16.1 24.5 35.5 535 782 Cantineid. Great Adil Key US Industrial Financial Ratios Exhibit 6 Swedish Match's Board of Directors, August 2005 Bernt Magnusson: Chairman of the Board Jan Blomberg Former CFO, Pharmacia Kenneth Ek: Labor representative w Sven Hindrikes: President and CEO Tuve Johannesson: Former president, Volvo Cars Arne Jurbrant: Former CEO, Kraft Foods Nordic Region Labor representative Eva Larsson: Joakim Lindstrm: Labor representative Karsten Slotte: President and CEO of snack food company cloetta Fazer Kersti Strandqvist Business area manager, SCA Baby Care Meg Tivus": President lottery operator Svenska Spel Exhibit 7 Comparable Company Data, 12/31/2004 (in SEK millions, except as noted) Swedish Match UST Imperial Tobacco BAT Galler Altadis 13.007 2,344 1 865 266 2,083 20% Summary Operating Data Net Sales EBITDA EBIT Interest Expense Net Income Dividend Payout Ratio ( Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Data Cash and Short-term Investments Total Assets Total Debt Non interest Bearing Total Equity 11.888 6 377 6,060 551 3.527 65% 35,447 15.915 12.180 2,741 5,349 73% 137.000 36 528 31,982 4.723 35.993 30% 32,428 8.811 7,677 1,974 4550 55% 86,460 9.624 8.112 1490 4.852 45 3.300 11.027 3,002 14.898 3.520 6.300 5.000 8.238 4,010 77262 50.540 23.064 3.000 24,662 226,308 01.353 57,074 77.881 9.689 55,154 37.831 18087 -764 9.954 96.446 27.720 55093 12.833 2.726 64 142 28.454 15.0x 52,823 23.4 131.484 17 x 233,667 17. 65.865 23.1 38.425 Stock Price Data Price/Earnings Ratio Equity Market Value Select Ratios Sales Growth EBITDA Margin Leverage at Book Values (debudebt plus equity) () Leverage at Market Values (debt debt plus market cap) (%) EBIT interest Coverage EBITDA Interest Coverage ) Total DEBITDA) -0.2% 18% 415 53% 54% 99% -6.3% 44% 94 18% 279 545 -15% 27% 1024 2.5 115 68% 11% 13% 28% 28% 36% 24% 70 88 1.5 11.0 110 13 44 5.8 32 6.8 7.7 2.5 39 4.5 5.4 0.4 29 Credit Rating A. BBB BBB BBB A