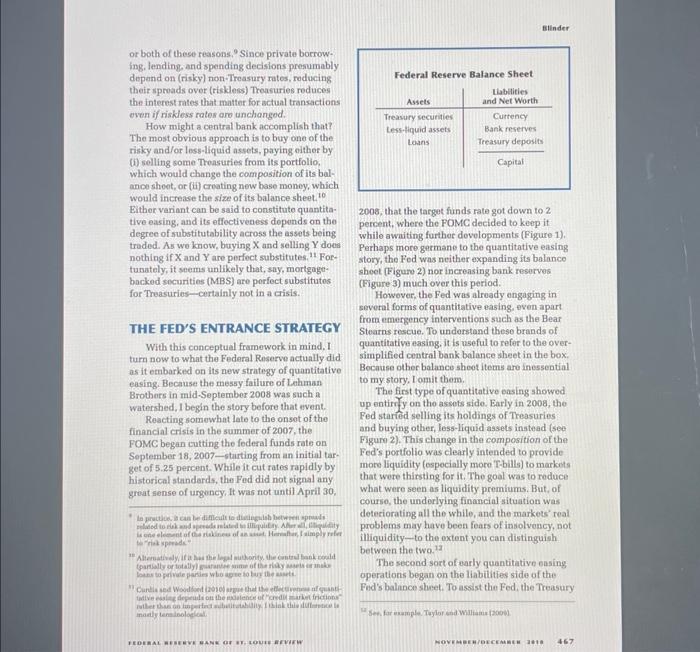

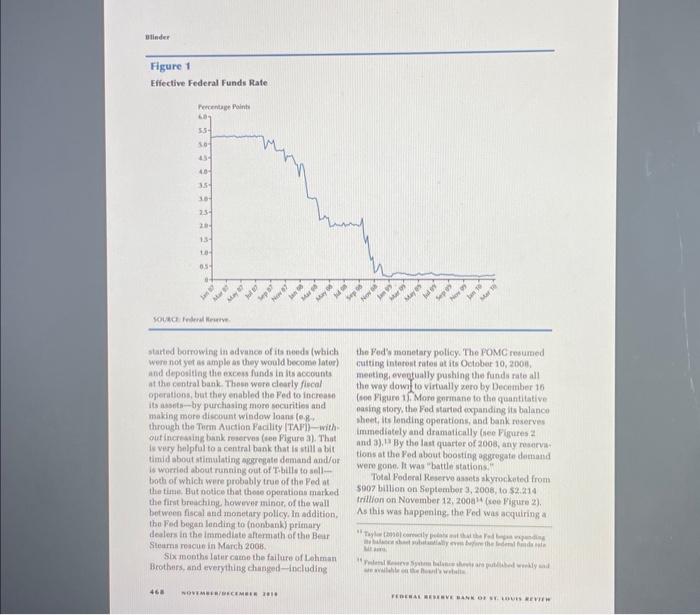

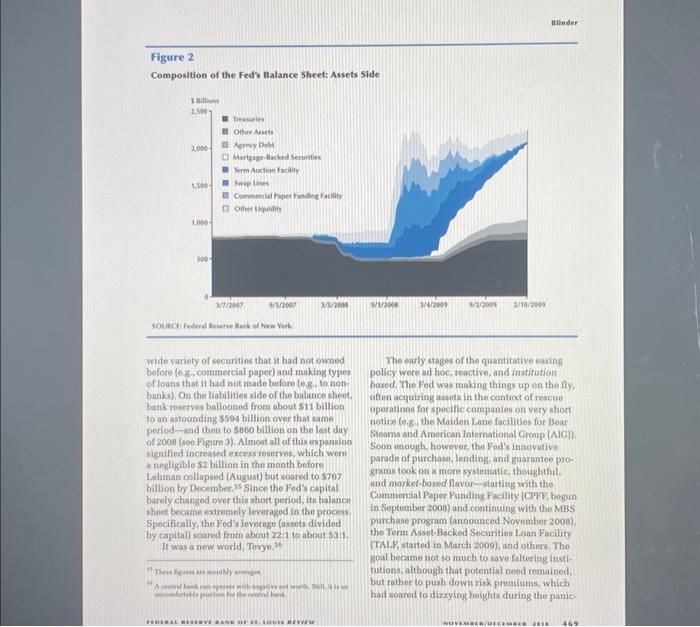

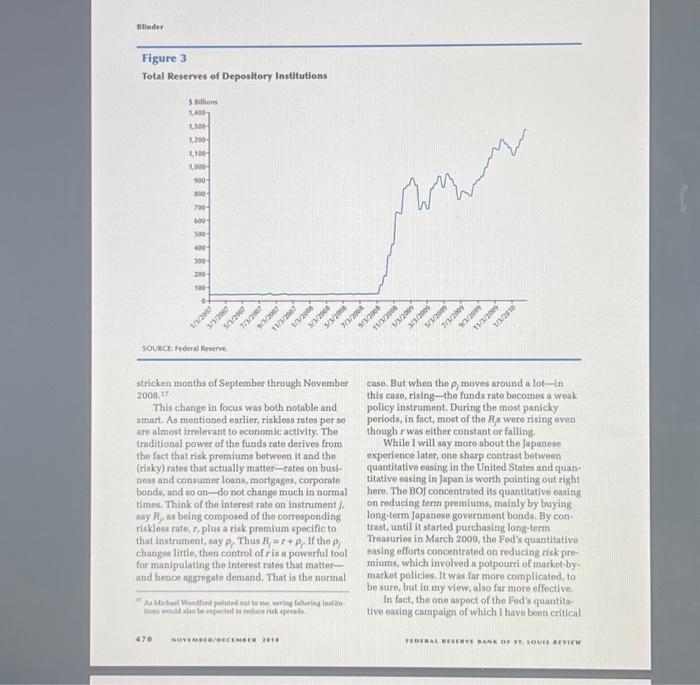

According to Blinder article:, two exit strategies of the Fed include: (i) increasing the interest on reserves and (ii) selling securities in conventional open-market operations. Use the Federal Fund Market (supply and demand for reserves) to show how each of (i) and (ii) leads to an increase in federal fund rate. Assume that currently (prior to the exit), the federal fund rate is at its floor. You need to draw the graphs to show your answer or you will not receive any points. (4 points) wide variety of securities that it had not owned before (o.g, commorcial pepec) and making types of loans that it had not made bofore (0.3, to non. banks). On the liabilities side of the balance sheet. bank rotarves ballooned from about $11 billion to an astounding $594 billion over that same peried-and then to 5660 billion on the last day of 200 (soe Figure 3). Almost all of this expansion signified increased excess reserves, which wern a negligible 52 billion in the month before Lohman collapsed (August) but soared to 5767 billion by December. 35 'Since the Fod's capital barely changed over this short poriod, its talanco shent became extrecnely leveragod in the process. Specifically, the Fed's leverage (assets divided by capital) soared from about 2211 to about 5311 . It was a now world, Tovye. ie The early stages of the quantitative easing policy were ad hoc, reactive, and institution basnd. The Fed was making things up on the fly, often acquiring ussets in the contoxt of rescue operations for spocific cormpanies on very short notion (e.g, the Maiden Lame facilities for Beat Steams and American International Ciroup (AIC)] Soon enough, however, the Fods innovative parade of purchase. lending, and guarantee programs took on a more systematic, thoughtful. and morket-based flavor starting with the Commorcial Paper Funding Fatility (CPFF, begun in September 2006) and continuing with the MBS purchase program (announced November 2008), the Term Assot-Backed Socurities Loan Facility (TALY, startod in March 2009), and otheri. Tho goal became not so much to save faltering institutions, although that potential need remuined. but rather to push down risk premiums, which had somed to dirzying heights during the panic- Total Reserves of Depository Institutions sounce rederal kenerve. stricken months of September through Novembet 2008,17 This change in focus was both notable and amart. As montioned earlier, riskless rates per so are almost irrelevant to economic activity. The traditional power of the funds rate derives from the fact that risk premiums botween it and the (risky) rates that actually matter-rates on busineas and consumer loans, mortgages, corporate bonds, and so on-do not change much in normal times. Think of the interest nate on instrument f. say Rp as boing composed of the corresponding riskless rate, r, plus a risk premium specific to that instrument, say r Thus Rj=r+pr If the pj changes little, then control of r is a powerlul tool for manipulating the interest rates that matterand hence aggregate demand. That is the normal case. But when the , moves around a lot - in this case, rising - the funds rate becomes a weak policy instrument. During the most panicky periods, in fact, most of the R/s wore rising oven though r was either constant or falling While I will say more about the Japanese experience later, one sharp contrast between quantitative easing in the United States and quantitative easing in Japan is worth pointing out right here. The BOJ concentrated its quantitative easing. on roducing torm premiums, mainly by buying long-term Japanese government bonds, By contrast, until it started purchasing long-term Treasuries in March 2009, the Fod's quantitative easing efforts concentrated on reducing risk premiums, which involved a potpourri of markot by: market policies, It was far more complicated, to be sure, but in my view, also far more effoctive. In fact, the one aspect of the Fed's quantitative easing campaign of which I have been critical 470 Novikeswotcemera 261 \% Effective Federal Funds Rate started botrowing it advance of ita noeds (which were not yet as ample as they would become later) and depositing the excess funds in its accounta at the central bank. These were clearly fiscal operations, but they enabled the Fed to increase its absets - by purchasing rore socurities aad making more disoount window loans (e.Rthrough the Term Auction Facility (TAF))- with. out increasiag bank reserves (uee Figure 3). That is very helpfal to a central bank that is still a bit timid about stimulating aygregate dimand and/or is worried about ruseing out of Thills ta sellboth of which were probably true of the Fed at the tiuse. But notice that those oponations marked the first breuchine, however minot, of the wall botwoen fiscal and monetary pollcy, in addition. the Fod began landing to (nonbank) ptitnary Aealers is the immediate afierasth of the Beir Steuma reacue in March 2006 . Six mooths latur caene the falure of Lohman Brothers, and everything changed-including the Fed' manetary policy. The FOMC resumed curting interest fatei at its Oetobar 10, 2000, meoting, eveotually pushing the funds fate all the way dowi to virfually zero by December 16 (see Figure 1). More gnrinane to the quantitative easing story, the Fod started expanding its balance sheet, its londing operations, and bank rvserves immediately and dramatically (hee Figures? and 3), 1 By the last quarter of 2008, any roserva. tions at the Fed about boosting aggrogate detnand were gone. It was "battle stations," Total Foderal Reservo assets akyrockated from 5907 billion on Septernbar 3, 2008, to $2.214 trillion on November 12;200a'4 (roe Figure 2), As this was happening. the Fed was acquiring a Mir 1rat 46a Quantitative Easing: Entrance and Exit Strategies Alan S. Blinder This article was originally presented as the Homor Joens Memorial Lecturt, ocganimed by thet Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louls, St. Louls, Miswouri, April 1, 2010 pparently, it cun happen here. On Decembat 16, 2008, the Federal Open Market Committeo (FOMC), in an effort to fight what was shaping up to be the worst recession since 193738, reduced the federal funds rate to nearly zera.' From then on, with all its conveational nmumumition spent, the Federal Reserve was squarely in the brave new worid of quantitative easing. Chairman Ben Bernanke tried to call the Fod's new policies "credit easing." probably to differentiate them from actions taken by the Bank of Jupan [BOD] earliet in the docado, but the label did not stick. Roughly spoaking, quantitative easing refers to changes in the composition and/or slixe of a central bank's balance sbeet that are designed to ease lifuidity and/ar crodit conditions. Presumably, reversing these policies constitutes "quantitative tightoring," but nobody soems to use that terminology. The discussion refers instesd to the bank's "exit strategy," Indicating that quantitative easing is something aberrant. I adbere to that nomenclature bete. I begin by sketiching the conceptaal basia for quantitative easing why it might be appropriate and how it is aupposed to work. I then tum to the Fod's entrunce strategy - which is presumably in the past, and then to the Fed's exil atrategywhich is still mostly in the future. Both strategies invite some briel comparisons with the lapanese experience between 2001 and 2006. Finally. 1 addrosis satne quentioes about ceatral bunk independence raised by quantitative easing before briefly wrappieg up. THE CONCEPTUAL BASIS FOR QUANTITATIVE EASING: THE LQUIDITY TRAP To begin with the okvious, Ithink every student of monetary policy believes that the central bank's corventional policy instrument - the overright interest tete the "fecleral funds" rate in the United States)-is more powertil and reliable than quantitative easing. So why would any rational central bunker ever resott to quantita: tive esasing? The answer is pretty dear Under is its purchases of Treasury bonds. The problem in many markets was that the sum r+, was too high-but mainly bocause of sky-high risk premiums, not high risk-free rates. Thus the true turget of epportunity was clearly pp not r, which was already very low. Furthermore, a steep yield curve provides profitable opportanitios for banks to recapitallwe thersselvos without taxpayer asristance. Why andermine that? In any case, the Fed's quantitative easing attack on intervit rate spreads appears to havo been succossful, at least in part. Figures 4 and 5 display two different interest rate spreads, one short torm and the othor lang term. Figare 4 shows the spread between the interest rates on 3 -month financial comenercial paper and 3-month Treasury bills: Figure 5 shows the spread between Moody's Baa-rated corporate bonds and 10-year Treasury notes. The dlagrams differ in dotails-for exam. ple, with ahort rates much more volatile than long rates. But both convey the samo basic messago: Once the Fed embarked on quantitative easing in a major way, spreads tumbled dramatically. Admittedly, other things were changing in marknts at the same time; so this was far from a controlled experiment. Still, the "colncidence" in timing is suggestive. THE FED'S EXIT STRATEGY The Fed's exit is still in its inlancy. Chalrman Bernanke first outlined the major components of its strategy in his July 2009 Congressional testi. mony, followed by a speech in October 2009 and further teatimonies in Fobruary and March 2010, in So by now wo have a pretty good picture of the Fed'y planned exil strategy. Here are the key ele. ments, listed ia what may or may not prove to be the corret temporal orderily 1. "In deaigning its [extraordinary liquidity] farlities, (the Fed) incorporated featureti. almed at encouraglng borrowers to reduce their use of the facilitios as financlal con: ditionu retureed to normal" (0,4, note) 2. "normalizing the terms of regular discount window loans" (p,4). 3. "passively redeeming ogency debt and MBS as they mature or are ropaid" (p. 0). 4. "Incroasing the interest on reserves" (p. 7), 20 5. "offer to depository institutions term deposits, which. .could not be counted as roserves" (p,8). 6. "roducing the quantity of roserves" via "reverso ropurchaso egroemonts" (p. 7). 7. "redeeming or selling securities" (p,) in conventional opea-tmatket oporations. Notice that this liut daftly omits any muntion of raising the federal funds rate. But the funds rato will presumably not wait until all the other stops have been completed. Indeed. Bernanke (2010a) noted that "the federal funds rate could for a time become a loss reliable indicator than usual of conditions in short-term money markets:" so that instend "it is possible that the Foderal Reserve could for a time use the interest rate paid on reserve. as a guido to its policy stance" (p,10). I will return to this not-mo-subtle hint shortly. The fint and third items on this list are the parts of "quantitative tightening" that the Fed gets for fren, analogous to letting assets run off naturally. As the Fed has noted repeatodily, Its special liquidity facilities were designed to be unattractive in normal times, and Item 1 is by now alinost completo. The Fed's two commercial peper facilities (one designod to save the money market mutual funds) outlived their usefulness, saw their usege drop to zero, and were officially closod on February 1, 2010. The same was true of the lending facility for primary dealers, the Term Securities Leoding Facility, and the extreordinary swap arrangements with foreige central banks. The TAF and the MBS purchase program had bees rocontly completed at that time, 21 and the TALY was slated to follow suit at the end of June 2010 or both of these reasons, 9 Since private borrowing. lending, and spending decisions presumably depand on (risky) non-Treasury rates, reducing their sproads over (riskless) Treasuries roduces the interest mites that matter for actual transactions even if riskless rator aro unchanged. How might a central bank accomplish that? The most obvious approach is to buy one of the risky and/or less-liquid assets, paying either by (i) selling some Troasuries from its portfolio, which would change the compasition of its balance sheot, or (ii) creating new base money, which would increase the size of its balance sheet. 10 Either variant can be said to constituto quantitative easing, and its effectiveness dopends on the degree of substitutability across the assets being traded. As we know, buying X and selling Y does nothing if X and Y are perfoct substitutes." Fortunately, it seems unlikely that, say, mortgagebacked socurities (MBS) aro porfect substitutos for Treasuries-certainly not in a crisis. THE FED'S ENTRANCE STRATEGY With this conceptual framework in mind, I turn now to what the Federal Reserve actually did as it embarked on its new strategy of quantitative easing. Because the messy failure of Lehman Brothers in mid-September 2008 was such a watershed, I begin the story before that event. Reacting somewhat late to the onset of the financial crisis in the summer of 2007 , the FOMC began cutting tho federal funds rate on September 18,2007 -starting from an initial target of 5.25 percent. While it cut rates rapidly by historical standerds, the Fed did not signal any great sense of urgoncy, It was not until April 30, the rias spreds" inaty teneinologleal 2008, that the target funds rate got down to 2 percent, where the FOMC decided to keep it while awaiting further dovelopments (Figure 1). Perhaps more germane to the quantitative easing story, the Fed was neither expanding its balance shoet (Figare 2) nor increasing bank reserves (Figure 3) much over this period. Howover, the Fed was already engaging in several forms of quantitative easing, even apart from emergency interventions such as the Bear Stearns rescue. To understand these brands of quantitative easing, it is useful to refer to the oversimplified central bank balance sheet in the box. Bocause other balance sheot items are inessential to my story, I omit them. The first type of quantitative easing showed up entirfy y on tho assets side. Early in 2008, the Fed staried selling its holdings of Treasuries and buying other, less-liquid assets instead (see Figure 2). This change in the composition of the Fed's portfolio was clearly intended to provide more liquidity (espocially more T-bills) to markets that were thirsting for it. The goal was to reduce what were seen as liquidity premiums. But, of course, the underlying financial situation was deteriorating all the while, and the markets' real problerns may have been fears of insolvency, not illiquidity - to the oxtent you can distinguish between the two..13 The second sort of early quantitative easing operations began on the liabilities side of the Fed's balance sheet. To assist the Fed, the Treasury Ia Sen far enample. Taylar snd wiliaina (acow) extremely adverse circumstances, a central bank con cut the nominal interest rate all tho way to zero and still be unable to stimulate its economy sufficiently. 2 Such a situation, in which the nominal rate hits its zero lower bound, has come to be called a "liquidity trap" (Krugman, 1998). although that terminology differs somewhat from Keynes's original moaning. Let's teview the underlying logic. The presumption is that real interest rates (r), not nominal interest rates (i), are what mainly matter for, say. afriegate demand. In deep recessions, monetary policymakers may noed to push real rates ( r=1, where is the rate of inflation) into negative territory. But onco i hits zero, the centril bank cannot force it down any farther, which loaves r "stuck" at , which is small or possibly even positive. In any case, once I^=0, conventional monetary policy is "out of bullets. Actually, the situation is even worse than that. Rocall Milton Friedman's (1968) warning about the perits of fixing the nominal interest rate when inflation is either rising or falling: Doing so Invites dynamic instablity. Well, once the nomi. nal rate is stuck at zero, it is, of course, fixed If inflation then falls, the real interest rate will rise farther, thereby squeezing the economy even more. This is a recipe for deflationary implosion. Enter quantitative easing. Suppose that, even though the riskless ovemight rate is constrained to zero, the central bank has some uncomventional policy instruments that it can uso to reduce interest rate spreads-such as term premiums and/or risk premiums. If flattening the yiold curve and/or shrinking risk premiums can boost aggregate demand, then monetary policy is not powerless. even at the zero lower bound 0 in that case, a cen. tral bank that pursues quantitative easing with sufficient vigor can break tho potentially vicious downward cyclo of deflation, weaker aggregato demand, more deflation, and so on. What unconventional weapons might be contained in such an arsenal? The following Hst is hypothetical and conceptual, but every item his a clear counterpart in something the Fedoral Reservo has actoally done. First. suppose the central bank's objective is to flatten the yield curve, perhaps because long rates have more powerful effects on spending than sbort rates. There are two main options. One is to use "open mouth policy." The central bank can cormunit to keeping the overnight rate at or near zero either for, say, "an extended period" (or somo such phraso) or until, say, inflation rises above a cortain level. To the extent that the (rational) expectations theory of the term structure is valid and the commitment is crodiblo, doing so should reduce long rates and thereby stimulate demand.? But such verbal commitments would not normally be considared quantitative easing because no quantity on the central bank's balance sheet is affected. So I will not discuss them further The quantitative easing approach to the term structure is straghtforward: Use otherwiseconventional open market purchases to acquire longer-term government securities instead of the short-term bies that central banks normally buy. If arbitrago al hig tho yield curvo is imperfoct, perhaps because asset holders have "preferred habitats, "then such operations can push long rates down by shrinking term premiums. The other likely target of quantitative easing is risk or liquidity spreads. Every private dobt instrument, even a bank deposit or a AAA-rated bond, pays some spread over Treasuries for ond While the expestaties therey of she terne itrecture with wi lemal if net by the righanout. macly igeop 466 Noventereforcauera zete Item 2 on this list (raising the discount rate) is necessary to supplement Itnm 1 (making botrowing less attractive), and the Fed began doing so with a surprise intermeeting move on February 18,2010. A higher discount rate is also needed if the Fed is to shift to the "corridor" system discussed later. Noto, however, that all these adjustmonts in liquidity facilities will still leave the Fed's balance sheot with the Bear Stearns and AIG assots and huge volumes of MBS and government-sponsored enterprise debt. Now that new purchases have stopped, the stocks of these two asset classes will gradually dwindle (Item 3 on the list). But unless there are aggressive open market sales, it will be a long time before the Fed's balance sheot resembles the status quo ante. That brings me to Items 6 and 7 on Bernanke's list, which are two types of conventional contractionary open market oporations, achioved eithor by reverse ropurchases (repos) (and thus tomporary) or by outright sales (and thus permanent). Transactions such as these have long ben famil. lar to anyone who pays attention to monetary policy, as are their normal effects on interest raten. Howover, thero is a key distinction between Items 1 and 3 (lending facilities), on the one hand. and Itoms 6 and 7 (open market oporations), on the other, when it comes to degree of difficulty. Quantitative easing under Itam 1, in particular. Wears off naturally on the markets' own rhythm: These special liquidity facilities fall into disuse as and when the markets no longer neod them. From the point of view of the central bank, this is ideal bocause the exit is perfoctly timod, almost by definition. Items 6 and 7 are differme. The FOMC will have to deride on the pace of its open market sules, Just as it does in any tightening cycle. But this time, both the volume and the varioty of asuets to be sold will probably be huge. Of course, the FOMC will get the usual market and macro signale: movemente in assot prices and intorest rates, the chatiging macro outlook, inflation and inflationary oxpoctations, and so on. But its deci. sionmaking will be more difficult, and more connequential, than usual because of the nnormoun scale of the tightesing. If the Fed tightens too quickly, it may stunt or evon abort the rocovery. If it waits too long, Inflation may gather steam. Once tho Fed's policy rutes aro lifted off zero, short-term interest nates will presumably be the Fed's main guidepost once again - more or less as in the past. This discussion leads naturally to ftem 5 on Bernanke's list, the novel plan to offer banks now types of accounts "which are roughly analogous to certificates of deposit" (p. 8). That is, instead of just having a "checking account" at the Fed, as at present, banks will be offered the option of buying various certificates of deposit (CDs) as well. But here's the wrinkle: Unlike their checking account balances at the Fed, the CDs will not count as official reserves. Thus, when a bank transfers money from its checking account to its saving account, bank reserves will simply vanish. The potential utility of this new instrument to a contral bank wanting to drain resorves is ovident, and the Fed has announced its intention to auction off fixed volumes of CDs of various maturitios, probably ranging from one to six months Such auctions would give it perfect control over the quantities but loayo the corresponding interest rates to be determined by the market. Frankly, 1 wonder why banks would find these new fixodincomo instruments attractive since they cannot be withdrawn before maturity, they do not constituto reserves, and they cannot serve as cloaring balances. As a consequenco, the new CDsmay have to bear interost rates higher than those on Treasury bills. We'll ses. I come, finally, to the instrument that Bernanke and the Fed soem to view as most central to their exit strategy the interest rate paid on bank reserves. Fed oflidals seem to view paying interest on reterves ais something akin to the magic bullot. t hope thay are right, but confess to being a bit worried. Everyone recomizes that the Fed y quanti. tative easing operations have created a veritable mountain of excess reserves (shown in Figure 3). which U.S. banks are currently holding voluntarIly, despite the paltry rates pald by the Fed. The question is thie How urgant in it-or will it become-to whittle this mountain down to sizel One view sees all those excess reserves as potential financial kindling that will prove infia. According to Blinder article:, two exit strategies of the Fed include: (i) increasing the interest on reserves and (ii) selling securities in conventional open-market operations. Use the Federal Fund Market (supply and demand for reserves) to show how each of (i) and (ii) leads to an increase in federal fund rate. Assume that currently (prior to the exit), the federal fund rate is at its floor. You need to draw the graphs to show your answer or you will not receive any points. (4 points) wide variety of securities that it had not owned before (o.g, commorcial pepec) and making types of loans that it had not made bofore (0.3, to non. banks). On the liabilities side of the balance sheet. bank rotarves ballooned from about $11 billion to an astounding $594 billion over that same peried-and then to 5660 billion on the last day of 200 (soe Figure 3). Almost all of this expansion signified increased excess reserves, which wern a negligible 52 billion in the month before Lohman collapsed (August) but soared to 5767 billion by December. 35 'Since the Fod's capital barely changed over this short poriod, its talanco shent became extrecnely leveragod in the process. Specifically, the Fed's leverage (assets divided by capital) soared from about 2211 to about 5311 . It was a now world, Tovye. ie The early stages of the quantitative easing policy were ad hoc, reactive, and institution basnd. The Fed was making things up on the fly, often acquiring ussets in the contoxt of rescue operations for spocific cormpanies on very short notion (e.g, the Maiden Lame facilities for Beat Steams and American International Ciroup (AIC)] Soon enough, however, the Fods innovative parade of purchase. lending, and guarantee programs took on a more systematic, thoughtful. and morket-based flavor starting with the Commorcial Paper Funding Fatility (CPFF, begun in September 2006) and continuing with the MBS purchase program (announced November 2008), the Term Assot-Backed Socurities Loan Facility (TALY, startod in March 2009), and otheri. Tho goal became not so much to save faltering institutions, although that potential need remuined. but rather to push down risk premiums, which had somed to dirzying heights during the panic- Total Reserves of Depository Institutions sounce rederal kenerve. stricken months of September through Novembet 2008,17 This change in focus was both notable and amart. As montioned earlier, riskless rates per so are almost irrelevant to economic activity. The traditional power of the funds rate derives from the fact that risk premiums botween it and the (risky) rates that actually matter-rates on busineas and consumer loans, mortgages, corporate bonds, and so on-do not change much in normal times. Think of the interest nate on instrument f. say Rp as boing composed of the corresponding riskless rate, r, plus a risk premium specific to that instrument, say r Thus Rj=r+pr If the pj changes little, then control of r is a powerlul tool for manipulating the interest rates that matterand hence aggregate demand. That is the normal case. But when the , moves around a lot - in this case, rising - the funds rate becomes a weak policy instrument. During the most panicky periods, in fact, most of the R/s wore rising oven though r was either constant or falling While I will say more about the Japanese experience later, one sharp contrast between quantitative easing in the United States and quantitative easing in Japan is worth pointing out right here. The BOJ concentrated its quantitative easing. on roducing torm premiums, mainly by buying long-term Japanese government bonds, By contrast, until it started purchasing long-term Treasuries in March 2009, the Fod's quantitative easing efforts concentrated on reducing risk premiums, which involved a potpourri of markot by: market policies, It was far more complicated, to be sure, but in my view, also far more effoctive. In fact, the one aspect of the Fed's quantitative easing campaign of which I have been critical 470 Novikeswotcemera 261 \% Effective Federal Funds Rate started botrowing it advance of ita noeds (which were not yet as ample as they would become later) and depositing the excess funds in its accounta at the central bank. These were clearly fiscal operations, but they enabled the Fed to increase its absets - by purchasing rore socurities aad making more disoount window loans (e.Rthrough the Term Auction Facility (TAF))- with. out increasiag bank reserves (uee Figure 3). That is very helpfal to a central bank that is still a bit timid about stimulating aygregate dimand and/or is worried about ruseing out of Thills ta sellboth of which were probably true of the Fed at the tiuse. But notice that those oponations marked the first breuchine, however minot, of the wall botwoen fiscal and monetary pollcy, in addition. the Fod began landing to (nonbank) ptitnary Aealers is the immediate afierasth of the Beir Steuma reacue in March 2006 . Six mooths latur caene the falure of Lohman Brothers, and everything changed-including the Fed' manetary policy. The FOMC resumed curting interest fatei at its Oetobar 10, 2000, meoting, eveotually pushing the funds fate all the way dowi to virfually zero by December 16 (see Figure 1). More gnrinane to the quantitative easing story, the Fod started expanding its balance sheet, its londing operations, and bank rvserves immediately and dramatically (hee Figures? and 3), 1 By the last quarter of 2008, any roserva. tions at the Fed about boosting aggrogate detnand were gone. It was "battle stations," Total Foderal Reservo assets akyrockated from 5907 billion on Septernbar 3, 2008, to $2.214 trillion on November 12;200a'4 (roe Figure 2), As this was happening. the Fed was acquiring a Mir 1rat 46a Quantitative Easing: Entrance and Exit Strategies Alan S. Blinder This article was originally presented as the Homor Joens Memorial Lecturt, ocganimed by thet Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louls, St. Louls, Miswouri, April 1, 2010 pparently, it cun happen here. On Decembat 16, 2008, the Federal Open Market Committeo (FOMC), in an effort to fight what was shaping up to be the worst recession since 193738, reduced the federal funds rate to nearly zera.' From then on, with all its conveational nmumumition spent, the Federal Reserve was squarely in the brave new worid of quantitative easing. Chairman Ben Bernanke tried to call the Fod's new policies "credit easing." probably to differentiate them from actions taken by the Bank of Jupan [BOD] earliet in the docado, but the label did not stick. Roughly spoaking, quantitative easing refers to changes in the composition and/or slixe of a central bank's balance sbeet that are designed to ease lifuidity and/ar crodit conditions. Presumably, reversing these policies constitutes "quantitative tightoring," but nobody soems to use that terminology. The discussion refers instesd to the bank's "exit strategy," Indicating that quantitative easing is something aberrant. I adbere to that nomenclature bete. I begin by sketiching the conceptaal basia for quantitative easing why it might be appropriate and how it is aupposed to work. I then tum to the Fod's entrunce strategy - which is presumably in the past, and then to the Fed's exil atrategywhich is still mostly in the future. Both strategies invite some briel comparisons with the lapanese experience between 2001 and 2006. Finally. 1 addrosis satne quentioes about ceatral bunk independence raised by quantitative easing before briefly wrappieg up. THE CONCEPTUAL BASIS FOR QUANTITATIVE EASING: THE LQUIDITY TRAP To begin with the okvious, Ithink every student of monetary policy believes that the central bank's corventional policy instrument - the overright interest tete the "fecleral funds" rate in the United States)-is more powertil and reliable than quantitative easing. So why would any rational central bunker ever resott to quantita: tive esasing? The answer is pretty dear Under is its purchases of Treasury bonds. The problem in many markets was that the sum r+, was too high-but mainly bocause of sky-high risk premiums, not high risk-free rates. Thus the true turget of epportunity was clearly pp not r, which was already very low. Furthermore, a steep yield curve provides profitable opportanitios for banks to recapitallwe thersselvos without taxpayer asristance. Why andermine that? In any case, the Fed's quantitative easing attack on intervit rate spreads appears to havo been succossful, at least in part. Figures 4 and 5 display two different interest rate spreads, one short torm and the othor lang term. Figare 4 shows the spread between the interest rates on 3 -month financial comenercial paper and 3-month Treasury bills: Figure 5 shows the spread between Moody's Baa-rated corporate bonds and 10-year Treasury notes. The dlagrams differ in dotails-for exam. ple, with ahort rates much more volatile than long rates. But both convey the samo basic messago: Once the Fed embarked on quantitative easing in a major way, spreads tumbled dramatically. Admittedly, other things were changing in marknts at the same time; so this was far from a controlled experiment. Still, the "colncidence" in timing is suggestive. THE FED'S EXIT STRATEGY The Fed's exit is still in its inlancy. Chalrman Bernanke first outlined the major components of its strategy in his July 2009 Congressional testi. mony, followed by a speech in October 2009 and further teatimonies in Fobruary and March 2010, in So by now wo have a pretty good picture of the Fed'y planned exil strategy. Here are the key ele. ments, listed ia what may or may not prove to be the corret temporal orderily 1. "In deaigning its [extraordinary liquidity] farlities, (the Fed) incorporated featureti. almed at encouraglng borrowers to reduce their use of the facilitios as financlal con: ditionu retureed to normal" (0,4, note) 2. "normalizing the terms of regular discount window loans" (p,4). 3. "passively redeeming ogency debt and MBS as they mature or are ropaid" (p. 0). 4. "Incroasing the interest on reserves" (p. 7), 20 5. "offer to depository institutions term deposits, which. .could not be counted as roserves" (p,8). 6. "roducing the quantity of roserves" via "reverso ropurchaso egroemonts" (p. 7). 7. "redeeming or selling securities" (p,) in conventional opea-tmatket oporations. Notice that this liut daftly omits any muntion of raising the federal funds rate. But the funds rato will presumably not wait until all the other stops have been completed. Indeed. Bernanke (2010a) noted that "the federal funds rate could for a time become a loss reliable indicator than usual of conditions in short-term money markets:" so that instend "it is possible that the Foderal Reserve could for a time use the interest rate paid on reserve. as a guido to its policy stance" (p,10). I will return to this not-mo-subtle hint shortly. The fint and third items on this list are the parts of "quantitative tightening" that the Fed gets for fren, analogous to letting assets run off naturally. As the Fed has noted repeatodily, Its special liquidity facilities were designed to be unattractive in normal times, and Item 1 is by now alinost completo. The Fed's two commercial peper facilities (one designod to save the money market mutual funds) outlived their usefulness, saw their usege drop to zero, and were officially closod on February 1, 2010. The same was true of the lending facility for primary dealers, the Term Securities Leoding Facility, and the extreordinary swap arrangements with foreige central banks. The TAF and the MBS purchase program had bees rocontly completed at that time, 21 and the TALY was slated to follow suit at the end of June 2010 or both of these reasons, 9 Since private borrowing. lending, and spending decisions presumably depand on (risky) non-Treasury rates, reducing their sproads over (riskless) Treasuries roduces the interest mites that matter for actual transactions even if riskless rator aro unchanged. How might a central bank accomplish that? The most obvious approach is to buy one of the risky and/or less-liquid assets, paying either by (i) selling some Troasuries from its portfolio, which would change the compasition of its balance sheot, or (ii) creating new base money, which would increase the size of its balance sheet. 10 Either variant can be said to constituto quantitative easing, and its effectiveness dopends on the degree of substitutability across the assets being traded. As we know, buying X and selling Y does nothing if X and Y are perfoct substitutes." Fortunately, it seems unlikely that, say, mortgagebacked socurities (MBS) aro porfect substitutos for Treasuries-certainly not in a crisis. THE FED'S ENTRANCE STRATEGY With this conceptual framework in mind, I turn now to what the Federal Reserve actually did as it embarked on its new strategy of quantitative easing. Because the messy failure of Lehman Brothers in mid-September 2008 was such a watershed, I begin the story before that event. Reacting somewhat late to the onset of the financial crisis in the summer of 2007 , the FOMC began cutting tho federal funds rate on September 18,2007 -starting from an initial target of 5.25 percent. While it cut rates rapidly by historical standerds, the Fed did not signal any great sense of urgoncy, It was not until April 30, the rias spreds" inaty teneinologleal 2008, that the target funds rate got down to 2 percent, where the FOMC decided to keep it while awaiting further dovelopments (Figure 1). Perhaps more germane to the quantitative easing story, the Fed was neither expanding its balance shoet (Figare 2) nor increasing bank reserves (Figure 3) much over this period. Howover, the Fed was already engaging in several forms of quantitative easing, even apart from emergency interventions such as the Bear Stearns rescue. To understand these brands of quantitative easing, it is useful to refer to the oversimplified central bank balance sheet in the box. Bocause other balance sheot items are inessential to my story, I omit them. The first type of quantitative easing showed up entirfy y on tho assets side. Early in 2008, the Fed staried selling its holdings of Treasuries and buying other, less-liquid assets instead (see Figure 2). This change in the composition of the Fed's portfolio was clearly intended to provide more liquidity (espocially more T-bills) to markets that were thirsting for it. The goal was to reduce what were seen as liquidity premiums. But, of course, the underlying financial situation was deteriorating all the while, and the markets' real problerns may have been fears of insolvency, not illiquidity - to the oxtent you can distinguish between the two..13 The second sort of early quantitative easing operations began on the liabilities side of the Fed's balance sheet. To assist the Fed, the Treasury Ia Sen far enample. Taylar snd wiliaina (acow) extremely adverse circumstances, a central bank con cut the nominal interest rate all tho way to zero and still be unable to stimulate its economy sufficiently. 2 Such a situation, in which the nominal rate hits its zero lower bound, has come to be called a "liquidity trap" (Krugman, 1998). although that terminology differs somewhat from Keynes's original moaning. Let's teview the underlying logic. The presumption is that real interest rates (r), not nominal interest rates (i), are what mainly matter for, say. afriegate demand. In deep recessions, monetary policymakers may noed to push real rates ( r=1, where is the rate of inflation) into negative territory. But onco i hits zero, the centril bank cannot force it down any farther, which loaves r "stuck" at , which is small or possibly even positive. In any case, once I^=0, conventional monetary policy is "out of bullets. Actually, the situation is even worse than that. Rocall Milton Friedman's (1968) warning about the perits of fixing the nominal interest rate when inflation is either rising or falling: Doing so Invites dynamic instablity. Well, once the nomi. nal rate is stuck at zero, it is, of course, fixed If inflation then falls, the real interest rate will rise farther, thereby squeezing the economy even more. This is a recipe for deflationary implosion. Enter quantitative easing. Suppose that, even though the riskless ovemight rate is constrained to zero, the central bank has some uncomventional policy instruments that it can uso to reduce interest rate spreads-such as term premiums and/or risk premiums. If flattening the yiold curve and/or shrinking risk premiums can boost aggregate demand, then monetary policy is not powerless. even at the zero lower bound 0 in that case, a cen. tral bank that pursues quantitative easing with sufficient vigor can break tho potentially vicious downward cyclo of deflation, weaker aggregato demand, more deflation, and so on. What unconventional weapons might be contained in such an arsenal? The following Hst is hypothetical and conceptual, but every item his a clear counterpart in something the Fedoral Reservo has actoally done. First. suppose the central bank's objective is to flatten the yield curve, perhaps because long rates have more powerful effects on spending than sbort rates. There are two main options. One is to use "open mouth policy." The central bank can cormunit to keeping the overnight rate at or near zero either for, say, "an extended period" (or somo such phraso) or until, say, inflation rises above a cortain level. To the extent that the (rational) expectations theory of the term structure is valid and the commitment is crodiblo, doing so should reduce long rates and thereby stimulate demand.? But such verbal commitments would not normally be considared quantitative easing because no quantity on the central bank's balance sheet is affected. So I will not discuss them further The quantitative easing approach to the term structure is straghtforward: Use otherwiseconventional open market purchases to acquire longer-term government securities instead of the short-term bies that central banks normally buy. If arbitrago al hig tho yield curvo is imperfoct, perhaps because asset holders have "preferred habitats, "then such operations can push long rates down by shrinking term premiums. The other likely target of quantitative easing is risk or liquidity spreads. Every private dobt instrument, even a bank deposit or a AAA-rated bond, pays some spread over Treasuries for ond While the expestaties therey of she terne itrecture with wi lemal if net by the righanout. macly igeop 466 Noventereforcauera zete Item 2 on this list (raising the discount rate) is necessary to supplement Itnm 1 (making botrowing less attractive), and the Fed began doing so with a surprise intermeeting move on February 18,2010. A higher discount rate is also needed if the Fed is to shift to the "corridor" system discussed later. Noto, however, that all these adjustmonts in liquidity facilities will still leave the Fed's balance sheot with the Bear Stearns and AIG assots and huge volumes of MBS and government-sponsored enterprise debt. Now that new purchases have stopped, the stocks of these two asset classes will gradually dwindle (Item 3 on the list). But unless there are aggressive open market sales, it will be a long time before the Fed's balance sheot resembles the status quo ante. That brings me to Items 6 and 7 on Bernanke's list, which are two types of conventional contractionary open market oporations, achioved eithor by reverse ropurchases (repos) (and thus tomporary) or by outright sales (and thus permanent). Transactions such as these have long ben famil. lar to anyone who pays attention to monetary policy, as are their normal effects on interest raten. Howover, thero is a key distinction between Items 1 and 3 (lending facilities), on the one hand. and Itoms 6 and 7 (open market oporations), on the other, when it comes to degree of difficulty. Quantitative easing under Itam 1, in particular. Wears off naturally on the markets' own rhythm: These special liquidity facilities fall into disuse as and when the markets no longer neod them. From the point of view of the central bank, this is ideal bocause the exit is perfoctly timod, almost by definition. Items 6 and 7 are differme. The FOMC will have to deride on the pace of its open market sules, Just as it does in any tightening cycle. But this time, both the volume and the varioty of asuets to be sold will probably be huge. Of course, the FOMC will get the usual market and macro signale: movemente in assot prices and intorest rates, the chatiging macro outlook, inflation and inflationary oxpoctations, and so on. But its deci. sionmaking will be more difficult, and more connequential, than usual because of the nnormoun scale of the tightesing. If the Fed tightens too quickly, it may stunt or evon abort the rocovery. If it waits too long, Inflation may gather steam. Once tho Fed's policy rutes aro lifted off zero, short-term interest nates will presumably be the Fed's main guidepost once again - more or less as in the past. This discussion leads naturally to ftem 5 on Bernanke's list, the novel plan to offer banks now types of accounts "which are roughly analogous to certificates of deposit" (p. 8). That is, instead of just having a "checking account" at the Fed, as at present, banks will be offered the option of buying various certificates of deposit (CDs) as well. But here's the wrinkle: Unlike their checking account balances at the Fed, the CDs will not count as official reserves. Thus, when a bank transfers money from its checking account to its saving account, bank reserves will simply vanish. The potential utility of this new instrument to a contral bank wanting to drain resorves is ovident, and the Fed has announced its intention to auction off fixed volumes of CDs of various maturitios, probably ranging from one to six months Such auctions would give it perfect control over the quantities but loayo the corresponding interest rates to be determined by the market. Frankly, 1 wonder why banks would find these new fixodincomo instruments attractive since they cannot be withdrawn before maturity, they do not constituto reserves, and they cannot serve as cloaring balances. As a consequenco, the new CDsmay have to bear interost rates higher than those on Treasury bills. We'll ses. I come, finally, to the instrument that Bernanke and the Fed soem to view as most central to their exit strategy the interest rate paid on bank reserves. Fed oflidals seem to view paying interest on reterves ais something akin to the magic bullot. t hope thay are right, but confess to being a bit worried. Everyone recomizes that the Fed y quanti. tative easing operations have created a veritable mountain of excess reserves (shown in Figure 3). which U.S. banks are currently holding voluntarIly, despite the paltry rates pald by the Fed. The question is thie How urgant in it-or will it become-to whittle this mountain down to sizel One view sees all those excess reserves as potential financial kindling that will prove infia