According to the article below:

2. What is the hypothesis?

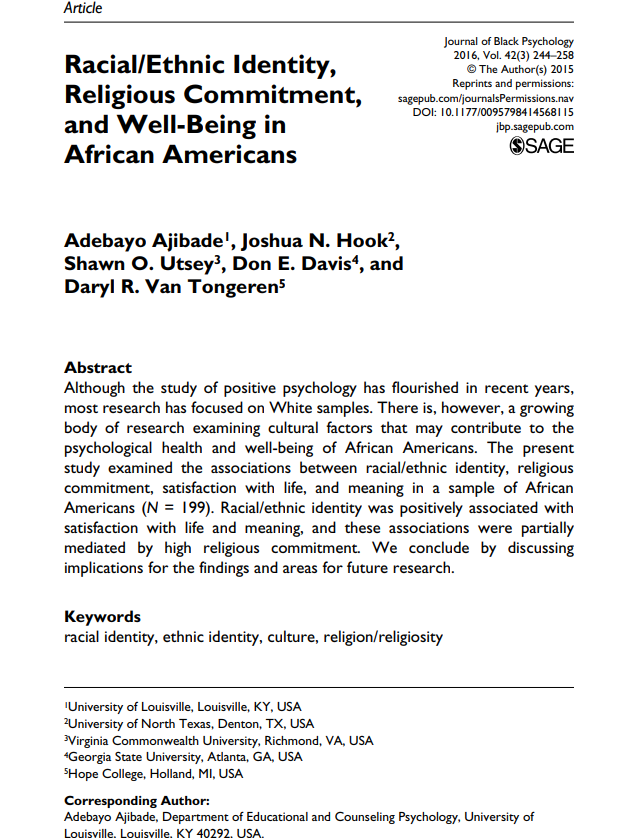

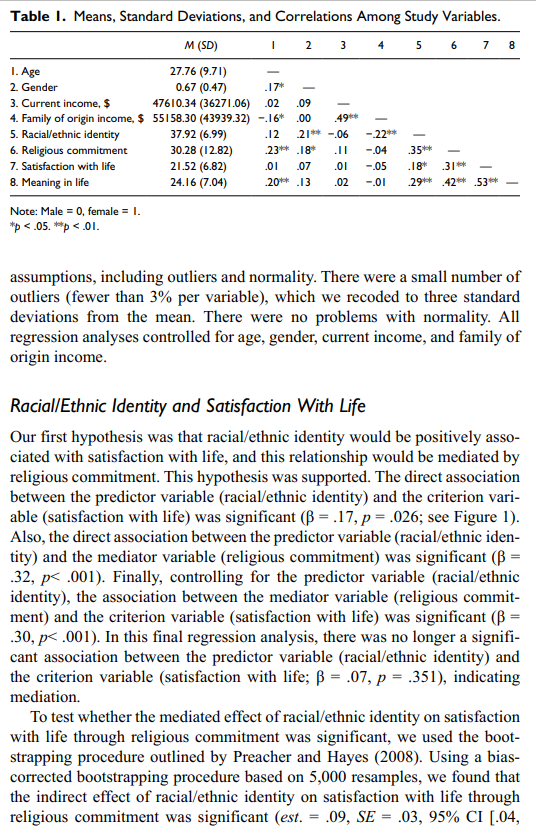

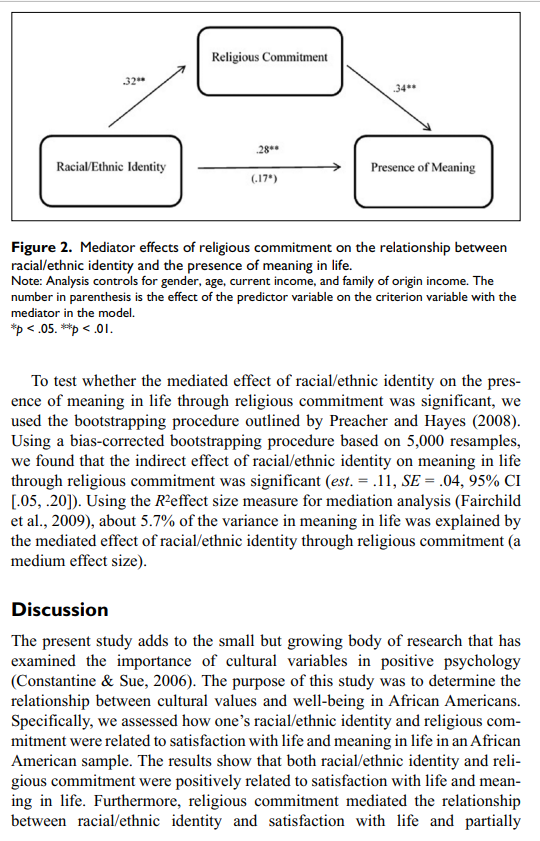

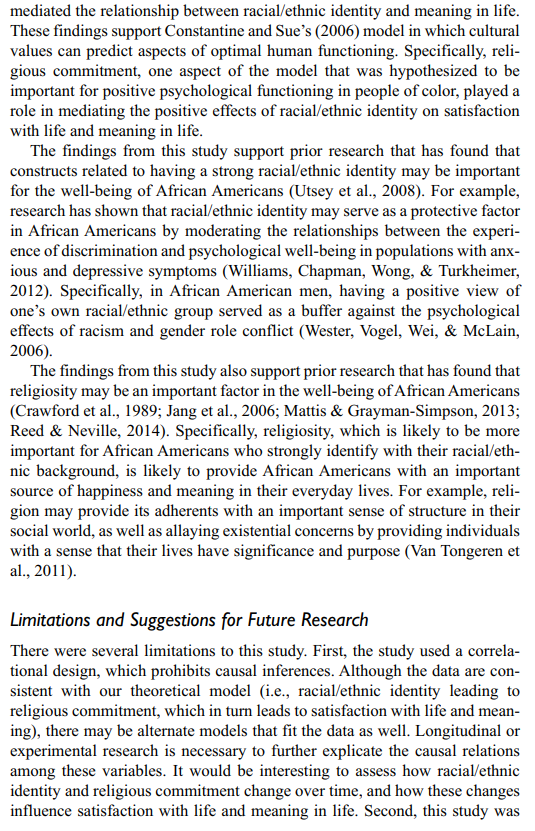

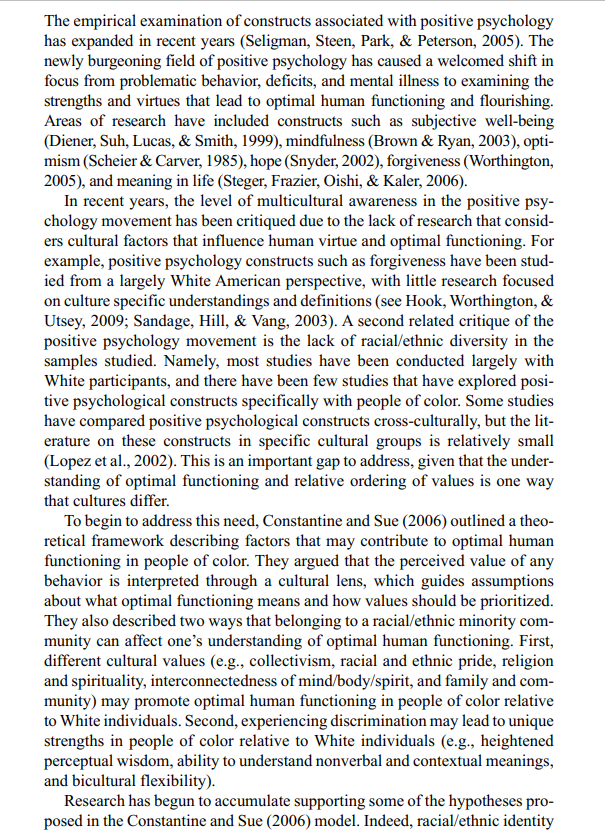

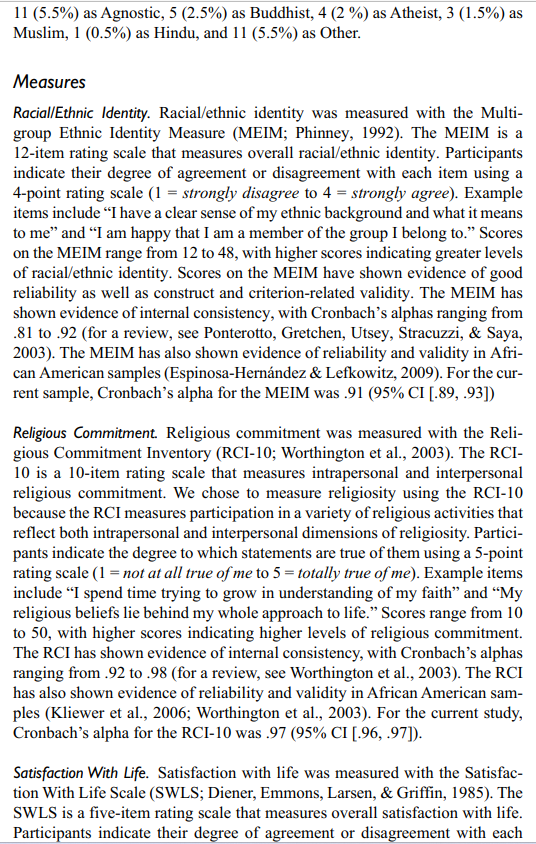

TranscribedText: Article Journal of Black Psychology Racial/Ethnic Identity, 2016, Vol. 42(3) 244-258 @ The Author(s) 2015 Religious Commitment, Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1 177/009579841 45681 15 and Well-Being in jbp-sagepub.com African Americans SSAGE Adebayojibade , Joshua N. Hook?, Shawn O. Utsey3, Don E. Davis*, and Daryl R. Van Tongeren5 Abstract Although the study of positive psychology has flourished in recent years, most research has focused on White samples. There is, however, a growing body of research examining cultural factors that may contribute to the psychological health and well-being of African Americans. The present study examined the associations between racial/ethnic identity, religious commitment, satisfaction with life, and meaning in a sample of African Americans (N = 199). Racial/ethnic identity was positively associated with satisfaction with life and meaning, and these associations were partially mediated by high religious commitment. We conclude by discussing implications for the findings and areas for future research. Keywords racial identity, ethnic identity, culture, religion/religiosity "University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA 2University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA *Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA SHope College, Holland, MI, USA Corresponding Author: Adebayojibade, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University of KY 40292. USA.Table I. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables. M (SD) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 I. Age 27.76 (9.71) 2. Gender 0.67 (0.47) 17* 3. Current income, $ 47610.34 (36271.06) .02 .09 4. Family of origin income, $ 55158.30 (43939.32) -.16* .00 5. Racial/ethnic identity 37.92 (6.99) 12 21* -.06 -.22#* 6. Religious commitment 30.28 (12 82) .23** .18* .II -.04 .35#* 7. Satisfaction with life 21.52 (6.82) 01 -.05 .18* 8. Meaning in life 24.16 (7.04) .20** .13 .02 -.01 .29** .42** .53** Note: Male = 0, female = 1. *p <.05. #p < .01. assumptions, including outliers and normality. There were a small number of outliers (fewer than 3% per variable), which we recoded to three standard deviations from the mean. There were no problems with normality. All regression analyses controlled for age, gender, current income, and family of origin income. Racial/Ethnic Identity and Satisfaction With Life Our first hypothesis was that racial/ethnic identity would be positively asso- ciated with satisfaction with life, and this relationship would be mediated by religious commitment. This hypothesis was supported. The direct association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic identity) and the criterion vari- able (satisfaction with life) was significant (B = .17, p = .026; see Figure 1). Also, the direct association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic iden- tity) and the mediator variable (religious commitment) was significant (B = 32, p< .001). Finally, controlling for the predictor variable (racial/ethnic identity), the association between the mediator variable (religious commit- ment) and the criterion variable (satisfaction with life) was significant (B = 30, p< .001). In this final regression analysis, there was no longer a signifi- cant association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic identity) and the criterion variable (satisfaction with life; B = .07, p = .351), indicating mediation. To test whether the mediated effect of racial/ethnic identity on satisfaction with life through religious commitment was significant, we used the boot- strapping procedure outlined by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Using a bias- corrected bootstrapping procedure based on 5,000 resamples, we found that the indirect effect of racial/ethnic identity on satisfaction with life through religious commitment was significant (est. = .09, SE = .03, 95% CI [.04,Religious Commitment Racial/Ethnic Identity Presence of Meaning (.17") Figure 2. Mediator effects of religious commitment on the relationship between racial/ethnic identity and the presence of meaning in life. Note: Analysis controls for gender, age, current income, and family of origin income. The number in parenthesis is the effect of the predictor variable on the criterion variable with the mediator in the model. *p <.05. #*p <.01. To test whether the mediated effect of racial/ethnic identity on the pres- ence of meaning in life through religious commitment was significant, we used the bootstrapping procedure outlined by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure based on 5,000 resamples, we found that the indirect effect of racial/ethnic identity on meaning in life through religious commitment was significant (est. = .11, SE = .04, 95% CI [.05, .20]). Using the Reffect size measure for mediation analysis (Fairchild et al., 2009), about 5.7% of the variance in meaning in life was explained by the mediated effect of racial/ethnic identity through religious commitment (a medium effect size). Discussion The present study adds to the small but growing body of research that has examined the importance of cultural variables in positive psychology (Constantine & Sue, 2006). The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between cultural values and well-being in African Americans. Specifically, we assessed how one's racial/ethnic identity and religious com- mitment were related to satisfaction with life and meaning in life in an African American sample. The results show that both racial/ethnic identity and reli- gious commitment were positively related to satisfaction with life and mean- ing in life. Furthermore, religious commitment mediated the relationship between racial/ethnic identity and satisfaction with life and partiallyReligious Commitment .3210 30# 17* Racial/Ethnic Identity Satisfaction with Life (.07. ns) Figure I. Mediator effects of religious commitment on the relationship between racial/ethnic identity and satisfaction with life. Note: Analysis controls for gender, age, current income, and family of origin income. The number in parenthesis is the effect of the predictor variable on the criterion variable with the mediator in the model. *p <.05. #*p <.01. .18]). Using the R effect size measure for mediation analysis (Fairchild, Mackinnon, Taborga, & Taylor, 2009), about 2.2% of the variance in satis- faction with life was explained by the mediated effect of racial/ethnic identity through religious commitment (a small effect size). Racial/Ethnic Identity and Meaning in Life Our second hypothesis was that racial/ethnic identity would be positively associated with the presence of meaning in life, and this relationship would be mediated by religious commitment. This hypothesis was also supported. The direct association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic identity) and the criterion variable (presence of meaning in life) was significant (B = .28, p< .001; see Figure 2). Also, the direct association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic identity) and the mediator variable (religious commit- ment) was significant (B = .32, p< .001). Finally, controlling for the predic tor variable (racial/ethnic identity), the association between the mediator variable (religious commitment) and the criterion variable (presence of meaning in life) was significant (B = .34, p< .001). In this final regression analysis, the association between the predictor variable (racial/ethnic iden- tity) and the criterion variable (religious commitment) remained significant but was reduced in magnitude (B = .17, p = .018), indicating partial mediation.personal and social habits in alignment with these values, and acting in line with one's understanding of one's values is theorized to promote meaning and psychological well-being (Van Tongeren, Hook, & Davis, 2013). For example, in a study of 140 African American adults, religiosity was posi- tively correlated with helping behavior as well as the level of satisfaction felt from helping behavior (Grayman-Simpson & Mattis, 2013). Fourth, religious groups provide a regular opportunity for individuals to gather with others committed to similar values, share their experiences, and receive support and validation from others with a similar worldview. For example, in a qualitative study of 23 African American women, religion and spirituality were impor- tant factors that helped African American women construct meaning in times of adversity (Mattis, 2002). Thus, it stands to reason that religious commit- ment may at least partially explain how identifying more strongly with one's racial/ethnic identity may lead to increases in psychological well-being. Overview and Hypotheses The purpose of the present study was to evaluate initial evidence for the links between racial/ethnic identity, religious commitment, and psychological well- being. Accordingly, we assessed cognitive and affective components of African American racial/ethnic identity, which included the understanding of, commit- ment to, and affirmation of, one's racial/ethnic identity (Roberts et al., 1999). Given the prominent role of religion in African American culture, we assessed religious commitment (Worthington et al., 2003) with a measure that incorpo rates intrapersonal (e.g., prayer) and interpersonal (e.g., church involvement) aspects of one's religious life. Psychological well-being was assessed with mea- sures of (a) life satisfaction and (b) meaning in life. Our primary hypothesis was that racial/ethnic identity would be positively associated with psychological well-being, and this association would be mediated by religious commitment. Method Participants Participants were 199 self-identified African Americans recruited from (a) a large university in the southeastern United States, (b) a large university in the southwestern United States, and (c) Amazon's Mechanical Turk website. Participants included 65 (32.7%) males, 133 (66.8%) females, and 1 (0.5%) gender queer individual. Their ages ranged from 18 to 64 years (M = 27.76; SD = 9.71). The mean yearly income was $47,610 (SD = 36,271). The mean yearly income from one's family of origin was $55,158 (SD = 43,939). Most (148, 73.4%) participants were Christian, 18 (9%) identified as nonreligious,Fairchild, A. J., Mackinnon, D. P., Taborga, M. P., & Taylor, A. B. (2009). R2 effect- size measures for mediation analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 486-498. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.486 Grayman-Simpson, N., & Mattis, J. S. (2013). Doing good and feeling good among African Americans: Subjective religiosity, helping, and satisfaction. Journal of Black Psychology, 39, 411-427. Hook, J. N., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Utsey, S. O. (2009). Collectivism, forgiveness, and social harmony. The Counseling Psychologist, 37, 821-847. Jang, Y., Borenstein, A. R., Chiriboga, D. A., Phillips, K., & Mortimer, J. A. (2006). Religiosity, adherence to traditional culture, and psychological well-being among African American elders. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 25, 343-355. Kliewer, W., Parrish, K. A., Taylor, K. W., Jackson, K., Walker, J. M., & Shivy, V. A. (2006). Socialization of coping with community violence: Influences of care- giver coaching, modeling, and family context. Child Development, 77, 605-623. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00893.x Lopez, S. J., Prosser, E. C., Edwards, L. M., Magyar-Moe, J. L., Neufeld, J. E., & Rasmussen, H. N. (2002). Putting positive psychology in a multicultural context. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 700- 714). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Lukwago, S. N., Kreuter, M. W., Bucholtz, D. C., Holt, C. L., & Clark, E. M. (2001). Development and validation of brief scales to measure collectivism, religiosity, racial pride, and time orientation in urban African American women. Family & Community Health, 24, 63-71. Mattis, J. S. (2002). Religion and spirituality in the meaning-making and coping experiences of African American women: A qualitative analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 309-321. Mattis, J. S., & Grayman-Simpson, N. A. (2013). Faith and the sacred in African American life. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA hand- book of psychology, religion, and spirituality: Vol. 1. Context, theory, and research (pp. 547-564). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Mattis, J. S., & Watson, C. R. (2008). Religiosity and spirituality. In B. M. Tynes, H. A. Neville, & S. O. Utsey (Eds.), Handbook of African American psychology (pp. 91-102). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Neville, H. A., & Lilly, R. L. (2000). The relationship between ethnic identity clus- ter profiles and psychological distress among African American college stu- dents. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 28, 194-207. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2000.tb00615.x Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164-172. Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156-176. doi:10.1177/074355489272003 Ponterotto, J. G., Gretchen, D., Utsey, S. O., Stracuzzi, T., & Saya, R. R. (2003). The multigroup ethnic identity measure (MEIM): Psychometric review andhas been linked with psychological well-being (Utsey, Hook, Fischer, & Belvet, 2008). Racial/ethnic identity refers to being involved, committed, and socially integrated into the traditions and practices of one's racial/ethnic group and having positive thoughts and attitudes about one's racial/ethnic group (Lukwago, Kreuter, Bucholtz, Holt, & Clark, 2001). Research suggests that actively embracing one's racial/ethnic identity may be an important ele- ment in buffering against the deleterious effects of racism, and in promoting the development of a sense of self-worth and psychological well-being (Utsey et al., 2008). Individuals with a strong racial/ethnic identity show lower lev- els of psychological distress and tend to have better mental health (Neville & Lilly, 2000). There are a variety of possible mechanisms for why racial/ethnic identity is associated with psychological well-being. Some scholars have proposed that religiosity-defined as "adherence to the prescribed beliefs and ritual practices associated with the worship of God or a system of gods" (Mattis & Watson, 2008, p. 92) may be a key mechanism for African Americans. Indeed, religiosity has been linked with psychological well-being in African Americans in prior research (Crawford, Handal, & Wiener, 1989; Jang, Borenstein, Chiriboga, Phillips, & Mortimer, 2006; Reed & Neville, 2014). Although studies have linked racial/ethnic identity, religiosity, and psy- chological well-being, we sought to uncover a more precise understanding of how these three constructs are related to each other. Specifically, we reasoned that African Americans with a strong sense of racial/ethnic identity might tend to become more socially embedded with others sharing a similar iden- tity. Given that many African Americans are religiously involved (i.e., 89% are religious, 78% attend services regularly, and 90% pray, meditate, or use religious materials; Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004), one's religious involve- ment is a potent way to do this. Prior work in this area has used various measures of religiosity, but we were specifically interested in how racial/ethnic identity might affect reli- gious commitment-"the degree to which a person adheres to his or her reli- gious values, beliefs, and practices and uses them in daily living" (Worthington et al., 2003, p. 85). Indeed, we posit that religious commitment provides a vital avenue for consolidating racial/ethnic identity in African Americans (Mattis & Grayman-Simpson, 2013). First, beliefs about God may involve one's highest ideals and values. Thus, for African Americans, religious beliefs provide a strong alternative to values lauded by the dominant culture. Second, religious communities pro- vide consensual validation of beliefs. Thus, for African Americans, increas ing religious commitment may weaken the influence of alternative narratives of the dominant culture. Third, religious communities encourage variousConclusion The rise of the positive psychology movement has allowed researchers to focus on questions related to human strengths and virtues. However, little theory and research have examined cultural factors that may contribute to positive psychological functioning, and research on positive psychology has generally used White samples. The present study adds to the small but grow- ing body of research examining how culture can be an important resource that may contribute to healthy psychological functioning and well-being. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publica- tion of this article. References Barnes, P. W., & Lightsey, O. J. (2005). Perceived racist discrimination, coping, stress, and life satisfaction. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 33, 48-61. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2005.tb00004.x Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848. Constantine, M. G., & Sue, D. (2006). Factors contributing to optimal human func- tioning in people of color in the United States. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 228-244. doi: 10.1177/0011000005281318 Crawford, M. E., Handal, P. J., & Wiener, R. L. (1989). The relationship between religion and mental health/distress. Review of Religious Research, 31, 16-22. Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi: 10.1207/ $15327752jpa4901_13 Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well- being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 Dorn, K., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Worthington, E. L., Jr. (2014). Behavioral methods of assessing forgiveness. Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 75-80. Espinosa-Hernandez, G., & Lefkowitz, E. S. (2009). Sexual behaviors and atti- tudes and ethnic identity during college. Journal of Sex Research, 46, 471-482. doi: 10.1080/00224490902829616further validity testing. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 502- 515. doi: 10.1177/0013164403063003010 Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879-891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 Reed, T. D., & Neville, H. A. (2014). The influence of religiosity and spirituality on psychological well-being among Black women. Journal of Black Psychology, 40, 384-401. doi: 10.1177/0095798413490956 Roberts, R. E., Phinney, J. S., Masse, L. C., Chen, Y., Roberts, C. R., & Romero, A. (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301-322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001 Sandage, S. J., Hill, P. C., & Vang, H. C. (2003). Toward a multicultural posi- tive psychology: Indigenous forgiveness and Hmong culture. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 564-592. doi: 10.1 177/001 1000003256350 Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219-247. Seligman, M. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychol- ogy progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Tidsskrift For Norsk Psykologforening, 42, 874-884. Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249-275. Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life ques- tionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80-93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 Steger, M. F., & Shin, J. Y. (2010). The relevance of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire to therapeutic practice: A look at the initial evidence. International Forum for Logotherapy, 33, 95-104. Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Levin, J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Tjeltveit, A. C. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and mental health. In S. J. Knapp, M. C. Gottlieb, M. M. Handelsman, & L. D. VandeCreek (Eds.), APA handbook of eth- ics in psychology: Vol. 1. Moral foundations and common themes (pp. 279-294). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Utsey, S. O., Hook, J. N., Fischer, N., & Belvet, B. (2008). Cultural orientation, ego resilience, and optimism as predictors of subjective well-being in African Americans. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 202-210. doi: 10.1080/17439760- 801999610 Van Tongeren, D. R., Green, J. D., Davis, J. L., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Hook, J. N., ... Greer, T. W. (201 1). Meaning as a restraint of evil. In J. H. Hellens (Ed.), Explaining evil: Vol. 3. Approaches, responses, solutions (pp. 203- 216). New York, NY: Praeger.mediated the relationship between racial/ethnic identity and meaning in life. These findings support Constantine and Sue's (2006) model in which cultural values can predict aspects of optimal human functioning. Specifically, reli- gious commitment, one aspect of the model that was hypothesized to be important for positive psychological functioning in people of color, played a role in mediating the positive effects of racial/ethnic identity on satisfaction with life and meaning in life. The findings from this study support prior research that has found that constructs related to having a strong racial/ethnic identity may be important for the well-being of African Americans (Utsey et al., 2008). For example, research has shown that racial/ethnic identity may serve as a protective factor in African Americans by moderating the relationships between the experi- ence of discrimination and psychological well-being in populations with anx- ious and depressive symptoms (Williams, Chapman, Wong, & Turkheimer, 2012). Specifically, in African American men, having a positive view of one's own racial/ethnic group served as a buffer against the psychological effects of racism and gender role conflict (Wester, Vogel, Wei, & Mclain, 2006). The findings from this study also support prior research that has found that religiosity may be an important factor in the well-being of African Americans (Crawford et al., 1989; Jang et al., 2006; Mattis & Grayman-Simpson, 2013; Reed & Neville, 2014). Specifically, religiosity, which is likely to be more important for African Americans who strongly identify with their racial/eth- nic background, is likely to provide African Americans with an important source of happiness and meaning in their everyday lives. For example, reli- gion may provide its adherents with an important sense of structure in their social world, as well as allaying existential concerns by providing individuals with a sense that their lives have significance and purpose (Van Tongeren et al., 2011). Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research There were several limitations to this study. First, the study used a correla- tional design, which prohibits causal inferences. Although the data are con- sistent with our theoretical model (i.e., racial/ethnic identity leading to religious commitment, which in turn leads to satisfaction with life and mean- ing), there may be alternate models that fit the data as well. Longitudinal or experimental research is necessary to further explicate the causal relations among these variables. It would be interesting to assess how racial/ethnic identity and religious commitment change over time, and how these changes influence satisfaction with life and meaning in life. Second, this study wasThe empirical examination of constructs associated with positive psychology has expanded in recent years (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). The newly burgeoning field of positive psychology has caused a welcomed shift in focus from problematic behavior, deficits, and mental illness to examining the strengths and virtues that lead to optimal human functioning and flourishing. Areas of research have included constructs such as subjective well-being (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999), mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003), opti- mism (Scheier & Carver, 1985), hope (Snyder, 2002), forgiveness (Worthington, 2005), and meaning in life (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). In recent years, the level of multicultural awareness in the positive psy- chology movement has been critiqued due to the lack of research that consid ers cultural factors that influence human virtue and optimal functioning. For example, positive psychology constructs such as forgiveness have been stud- ied from a largely White American perspective, with little research focused on culture specific understandings and definitions (see Hook, Worthington, & Utsey, 2009; Sandage, Hill, & Vang, 2003). A second related critique of the positive psychology movement is the lack of racial/ethnic diversity in the samples studied. Namely, most studies have been conducted largely with White participants, and there have been few studies that have explored posi- tive psychological constructs specifically with people of color. Some studies have compared positive psychological constructs cross-culturally, but the lit- erature on these constructs in specific cultural groups is relatively small (Lopez et al., 2002). This is an important gap to address, given that the under- standing of optimal functioning and relative ordering of values is one way that cultures differ. To begin to address this need, Constantine and Sue (2006) outlined a theo- retical framework describing factors that may contribute to optimal human functioning in people of color. They argued that the perceived value of any behavior is interpreted through a cultural lens, which guides assumptions about what optimal functioning means and how values should be prioritized. They also described two ways that belonging to a racial/ethnic minority com- munity can affect one's understanding of optimal human functioning. First, different cultural values (e.g., collectivism, racial and ethnic pride, religion and spirituality, interconnectedness of mind/body/spirit, and family and com- munity) may promote optimal human functioning in people of color relative to White individuals. Second, experiencing discrimination may lead to unique strengths in people of color relative to White individuals (e.g., heightened perceptual wisdom, ability to understand nonverbal and contextual meanings, and bicultural flexibility). Research has begun to accumulate supporting some of the hypotheses pro- posed in the Constantine and Sue (2006) model. Indeed, racial/ethnic identity11 (5.5%) as Agnostic, 5 (2.5%) as Buddhist, 4 (2 %) as Atheist, 3 (1.5%) as Muslim, 1 (0.5%) as Hindu, and 11 (5.5%) as Other. Measures Racial/Ethnic Identity. Racial/ethnic identity was measured with the Multi- group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992). The MEIM is a 12-item rating scale that measures overall racial/ethnic identity. Participants indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with each item using a 4-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Example items include "I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me" and "I am happy that I am a member of the group I belong to." Scores on the MEIM range from 12 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater levels of racial/ethnic identity. Scores on the MEIM have shown evidence of good reliability as well as construct and criterion-related validity. The MEIM has shown evidence of internal consistency, with Cronbach's alphas ranging from 81 to .92 (for a review, see Ponterotto, Gretchen, Utsey, Stracuzzi, & Saya, 2003). The MEIM has also shown evidence of reliability and validity in Afri- can American samples (Espinosa-Hernandez & Lefkowitz, 2009). For the cur- rent sample, Cronbach's alpha for the MEIM was .91 (95% CI [.89, .93]) Religious Commitment. Religious commitment was measured with the Reli- gious Commitment Inventory (RCI-10; Worthington et al., 2003). The RCI- 10 is a 10-item rating scale that measures intrapersonal and interpersonal religious commitment. We chose to measure religiosity using the RCI-10 because the RCI measures participation in a variety of religious activities that reflect both intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions of religiosity. Partici- pants indicate the degree to which statements are true of them using a 5-point rating scale (1 = not at all true of me to 5 = totally true of me). Example items include "I spend time trying to grow in understanding of my faith" and "My religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life." Scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of religious commitment. The RCI has shown evidence of internal consistency, with Cronbach's alphas ranging from .92 to .98 (for a review, see Worthington et al., 2003). The RCI has also shown evidence of reliability and validity in African American sam- ples (Kliewer et al., 2006; Worthington et al., 2003). For the current study, Cronbach's alpha for the RCI-10 was .97 (95% CI [.96, .97]). Satisfaction With Life. Satisfaction with life was measured with the Satisfac tion With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The SWLS is a five-item rating scale that measures overall satisfaction with life. Participants indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with eachbased exclusively on self-report data, which have several limitations, include ing response biases and social desirable responding. Although it a relatively common problem for positive psychological constructs to be assessed solely with self-report measures (Dorn, Hook, Davis, Van Tongeren, & Worthington, 2014), it would be interesting to use other types of measures as well (e.g., behavioral measures). In addition to using more sophisticated research designs and measure- ment strategies, future research could examine these ideas using more het- erogenous samples of African Americans. It would be interesting to assess whether these associations held across the life span (e.g., older adults). Also, future research could further explore the construct of religion to identify which aspects of religion are most helpful to African Americans. Perhaps there are some versions of religion that are more or less helpful in African American communities. Furthermore, future research could explore the spe- cific mechanisms by which religion influences well-being in African Americans, such as social support or self-regulation. Finally, the current study focused primarily on one cultural factor that was thought to be impor- tant to African Americans (i.e., religion). Future research could assess other aspects of African American culture (e.g., collectivism, interconnectedness of mind/body/spirit). Practical Implications The results of this study hold several implications for clinicians or commu- nity psychologists who are working to help African American clients or com- munities. Namely, the study found that having high levels of racial/ethnic identity and religious commitment were positively associated with satisfac tion with life and meaning for African American individuals. Counselors working with African American clients may want to assess the client's racial/ ethnic identity to see if the client's views toward his or her cultural back- ground could be helping or hindering working toward one's goals in counsel- ing. Counselors should also assess for religious commitment and inquire whether that is a topic that clients may want to address. If the client identifies one's racial/ethnic identity or religion as an area of interest or struggle, coun- selors could design interventions targeting those areas. For example, counsel- ors could consider how racial/ethnic identity and religion affect the client's functioning and consider how they may help promote optimal functioning in the client. Incorporating positive images of African Americans may help buf- fer against the negative images and stereotypes propagated in the media (Utsey et al., 2008). Similarly, the inclusion of religion in therapy may help aid in the therapeutic process (Tjeltveit, 2012).item using a 'i-point rating scale [1 =.rtmngiy disagree to If" = strength; agree). Example items include "In most ways, my life is close to my ideal" and "So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life." Scores on the SWLS range from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. The SWLS have shown evidence of internal consistency. with an average Cronl bach's alpha of .83 {for review, see Pavot St Diener, [993]. The SWLS has also shown evidence of reliability and validity in African American samples [Barnes Sc Lightsey, 2005]. For the current study, Cronbach's alpha for the SWLS was .88 {95% CI {.85, .901}. Meaning in Life. Meaning in life was measured with the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al., 2006). The MLQ is a [04item rating scale that measures two dimensions ofmeaning in life: (a) the presence ofmeaning and (b) the search for meaning. In this study, we used the presence ofmean ing in life subscale [MLQ-P}. Participants indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with each item using a Tapoint rating scale {I = absolutely true to 7 = absolutely untrue]. Example items include "I understand my life's meaning" and "I have discovered a satisfying life purpose." Scores on the MLQ-P range from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater levels of meaning in life. The MLQ-P has shown evidence of internal consistency, with Cronbaeh's alpha ranging from .3} to .88 [for a review, see Steger et al., 2006]. The MLIQI has shown some evidence for reliability and validity in non White samples (Steger 8:. Shin, 2010). For the current study, Cronbach's alpha for the MLQuP was .91 (95%{31 [.39. 93]). Procedure The study was approved by the institutional review board. Participants were recruited from undergraduate classes or via the Amazon Mechanical Turk website. Participants recruited from undergraduate classes were given a small amount of course credit. Participants recruited from Mechanical Turk were given a small amount of monetary compensation ($0.20}. All participants, prior to completing the questionnaire, were brie fed on the study's procedures and their rights as participants, and their consent was obtained. After giving consent, participants completed the questionnaires. Following the comple tion of the questionnaire, they were given the contact information of the researcher should they have any questions regarding the study. Results Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables are in Table 1. Prior to conducting the primary analyses, we checked the data for

Article Racial/Ethnic Identity, Religious Commitment, and Well-Being in African Americans Journal of Black Psychology 2016, Vol. 42(3) 244-258 The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0095798414568115 jbp.sagepub.com $SAGE Adebayo Ajibade', Joshua N. Hook, Shawn O. Utsey, Don E. Davis*, and Daryl R. Van Tongeren Abstract Although the study of positive psychology has flourished in recent years, most research has focused on White samples. There is, however, a growing body of research examining cultural factors that may contribute to the psychological health and well-being of African Americans. The present study examined the associations between racial/ethnic identity, religious commitment, satisfaction with life, and meaning in a sample of African Americans (N = 199). Racial/ethnic identity was positively associated with satisfaction with life and meaning, and these associations were partially mediated by high religious commitment. We conclude by discussing implications for the findings and areas for future research. Keywords racial identity, ethnic identity, culture, religion/religiosity 'University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA 2University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA *Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA SHope College, Holland, MI, USA Corresponding Author: Adebayo Ajibade, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University of Louisville. Louisville, KY 40292. USA.