Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

All answers must be supported by arguments and reasoning. Simply providing your opinion without providing substantive supporting arguments is unacceptable and will adversely impact your

All answers must be supported by arguments and reasoning. Simply providing your opinion without providing substantive supporting arguments is unacceptable and will adversely impact your grade.

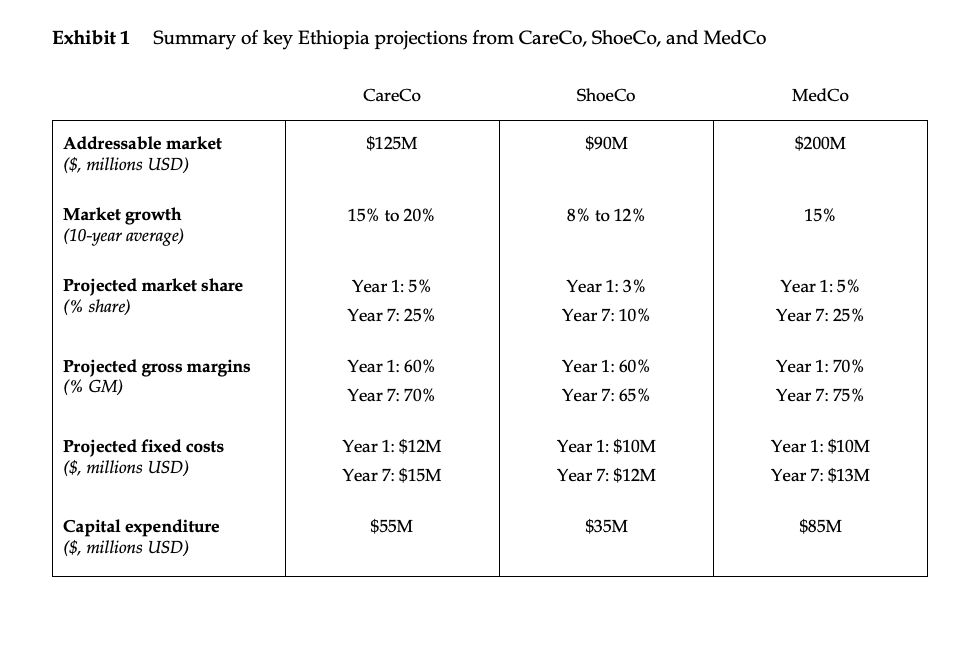

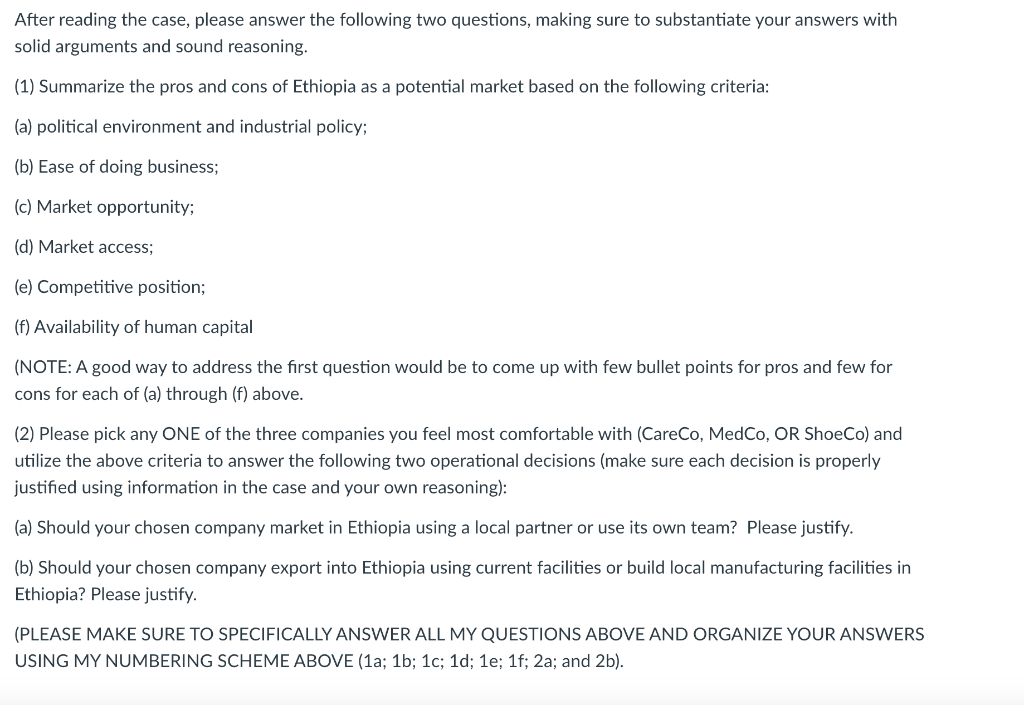

In January 2014, three companies were debating whether they should extend their operations to the emerging market of Ethiopia. Since the 1990s, economic reforms and liberalization had opened opportunities for foreign direct investment, and businesses from many countries were already active there. All three companies believed that they needed to decide what to do soon. In a London boardroom, the director of global strategy at CareCo argued, "The purchasing power of Ethiopian consumers will only grow. If we move in now, we ensure that our brands are established. If we wait, competitors will have time to build brand awareness and tie up distribution channels. We cannot miss this window of opportunity!" A similar conversation was under way in Beijing, where the ShoeCo executive team debated the merits of the Ethiopian opportunity. The vice president of global sales commented, "The labor costs in Ethiopia are low. A factory there would give us a great cost position to serve the local and regional markets. This would require significant expenditure and risk, but could establish us there." At the MedCo headquarters in Abu Dhabi, the chief operating officer cited the expected growth in health care spending and MedCo's own track record, and noted, "Demand in Ethiopia will grow quickly for the next 15 or 20 years. We offer good quality at a lower cost than competitors do. This value proposition has been our blueprint for success!" Historical Background The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Eritrea to the north, Djibouti and Somalia to the east, Sudan and South Sudan to the west, and Kenya to the south. Many Ethiopians believe their country is distinct from its immediate neighbors and the rest of sub-Saharan Africa because of its religious and cultural history and its success in warding off numerous attempts to colonize the nation. From 1974 until 1991, Ethiopia was ruled by a Soviet-backed military junta. This regime was marked by human rights abuses and corruption. Under its rule, Ethiopia suffered a series of famines that left one million people dead and drew worldwide attention. These events led many foreigners to associate the country with poverty and starvation, a perception that still lingered. In 1991, the Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) overthrew the standing government. Following several years of transition, a new constitution was written in 1994. The EPRDF was victorious when formal elections took place in 1995. The government had remained stable since then and had run the country as a single-party state. Starting in the mid-1990s, the government invited private companies to compete in sectors that the state had controlled. More than 300 state-owned enterprises had been privatized, attracting both domestic and foreign investors. The government also eased the administrative burden of starting a business and revised the tax code to encourage private enterprise. Industrial Policy and Market Opportunities Between 2003 and 2013, Ethiopia's population increased by 30%, to 94 million people, and its GDP increased from $8.6 billion to $47.5 billion. 1 Economic growth had occurred relatively more in the service and agricultural sectors than it had in the manufacturing sector. In a recent report that assessed the market opportunities for 54 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Ethiopia had ranked sixth. 2 The Ethiopian government adhered to a state-led development model. Massive public investments in transportation, power, and telecommunications infrastructure were key drivers of economic growth. Public investments accounted for nearly one-third of GDP. Yet, with public debt at 23% of GDP, the government still had capacity to finance its projects. 3 Improvement of road infrastructure and power generation, in particular, was expected to pay long-term dividends in fostering private-sector growth and attracting foreign capital. New rail and road corridors to modern seaports in Djibouti were intended to mitigate the challenges of being a landlocked country and give access to a trade route that accounted for 30% of global container traffic. 4 The government also had a presence in sectors it considered important. Areas of state monopoly or dominance included telecommunications, power, financial services, air transport, and shipping. Both domestic and foreign firms complained about unfair competition when dealing with state-owned and party-affiliated businesses. Such companies were perceived to have an advantage in accessing credit, navigating government bureaucracy, winning government tenders, and clearing customs. The Ethiopian government attempted to protect local companies and encourage import substitution, while attracting inflows of foreign direct investment. It reserved some industries for domestic firms only, such as the media, retail, and transportation industries. Similarly, the financial sector was reserved for domestic investors, and most bank assets were held by state-run banks. The government also promoted certain sectors, such as domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing. 5 The government also attempted to attract foreign investment for local manufacturing and exportoriented sectors that needed inflows of technology and knowledge. It provided income-tax exemptions, for up to five years, to investors who established enterprises in manufacturing, agro-processing, and the production of agricultural products. Enterprises in targeted areas of underdevelopment could enjoy an additional tax deduction after the standard exemption period had expired. Ethiopia also granted customs exemptions for capital goods, such as plants, machinery, equipment, spare parts, and construction materials. The law protected private property and permitted investors to convert capital and profit into foreign currency. Despite this policy, there had been shortages of foreign exchange due to the country's trade imbalance, with imports far exceeding exports. Overall, the World Bank ranked Ethiopia 129th of 189 countries in its global rankings for ease of doing business. 6 However, Ethiopia ranked within the top third of countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Investing in Ethiopia Foreign companies deciding whether to invest in Ethiopia had to consider several other factors: Infrastructure Ethiopia was near the bottom of the World Bank's ranking of countries for facilitation of cross-border trade and logistics performance. 7 Even with a modern air-cargo terminal, Ethiopia depended on the port of Djibouti for surface shipments. 8 Although the road infrastructure between cities had improved, more than one-third of the population still lived five or more hours from a city. Although the government was constructing a high-speed rail and multi-lane highway connection to bordering countries, logistics costs were expected to remain high in the near term. There were other infrastructure limitations. The power grid had been upgraded, but power cuts remained frequent. Many businesses had to rely on expensive backup generators. Likewise, the quality of telecommunications was spotty and Internet outages were frequent. Human resources Ethiopia was cost competitive with China for light production. 9 It also produced more than 10,000 university graduates each year, creating a supply of skilled, affordable employees. Some foreign employers, particularly from the United States and Europe, believed that the gaps between expatriate and local employees in work culture, management style, and communication were difficult to bridge. Many foreign businesses viewed native Ethiopians who had worked elsewhere and returned as the best-trained talent, but such hires were relatively scarce and costly. Limited competition Many Ethiopian industries were still developing, so firms with greater marketing resources or superior products could capture market share more easily. Yet the limited competition also created opportunities for upstarts that could negate the advantages of an established multinational. Because Ethiopia had long been closed to foreign influence, global brands did not enjoy the same awareness among consumers. Fragmented distribution channels Distributors sourced many goods from Mercato, the large wholesale market in Addis Ababa, and relied on sub-distributors to serve retailers outside cities to rural areas, where more than 75% of Ethiopia's citizens lived. There were no international retailers and very few retail chains with a significant footprint; small independent outlets and kiosks remained the largest channel. Servicing so many small players was costly. Some wholesalers, particularly in consumer goods, argued that a realistic estimate of the addressable market had to exclude households outside of urban areas. Because wholesaling of any imported goods was restricted to domestic firms, importers had to work with local partners. Any firm engaged in local manufacturing was free to manage its own wholesaling and distribution, but some foreign companies found it difficult to navigate the distribution networks and manage customer relationships without local partners. Cross-cultural adaptation and customer relations Entering Ethiopia required an understanding of local customs, norms, and expectations. In consumer marketing, for example, companies could inadvertently offend a particular group with the wrong choice of music or spokesperson. Other companies, particularly those engaged in selling goods and services on a business-to-business basis, reported challenges in building trust with potential customers. To mitigate this risk, some global professional services companies had formed joint ventures with local firms. 10 Intellectual property Enforcement of protection for intellectual property was unreliable. Ethiopia had not signed all of the major international intellectual-property treaties, and the Ethiopian HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL | BRIEFCASES Intellectual Property Office focused on protecting Ethiopian materials and copyrights. Furthermore, its capacity for law enforcement was limited, and numerous businesses used well-known names and trademarks without permission. Counterfeit and pirated products were also common. Corruption Public-sector corruption was suspected to be high. In 2013, Transparency International ranked Ethiopia 111th of 177 rated countries in perceived public-sector corruption. 11 Foreign investors had complained about the lack of transparency in government tenders. Many believed that select firms received preferential treatment. Market Entry Options Foreign businesses had four ways of entering the Ethiopian market. Local agent or importer Non-Ethiopian businesses were barred from wholesale trade and retailing, except for locally produced goods. For multinational businesses that exported to Ethiopia, working through a local partner was the only way to sell. An Ethiopian partner had existing relationships and knew how to manage the local distribution channels and other on-the-ground challenges. Although the multinational had less control over sales and marketing, it was a low-risk way to enter the market. Licensing arrangement Foreign businesses could license their brand, technology, or products to local partners or designate a local franchisee. Having goods produced locally allowed for more competitive pricing and access to the local partner's understanding of how to sell and distribute in local markets. The margins for this approach were typically thinner, and there was risk of infringement on intellectual property. Licensing and franchising were relatively rare compared to other modes of market entry. Joint venture In a joint venture, multinational corporations could maintain greater control while benefiting from the advantages offered by a local partner. The local partner could be a private entity or the government, which might keep an equity stake. However, multinationals that planned to export most of their output or to reinvest profits in the joint venture were exempt from this requirement. Subsidiary A foreign parent could set up wholly owned subsidiary or branch as a limited liability company. With a subsidiary, a multinational could avoid coordination and alignment issues with any local partners and protect proprietary technology or know-how. Opportunities for Three Potential Entrants Each company had to consider whether it could succeed in Ethiopia. See Exhibit 1 for a summary of each company's projections and estimates for entering Ethiopia. CareCo Axel Kazuo, the new director of global strategy at CareCo, made his case to the executive team: "All our flagship brands are struggling to catch up with the competition in key markets - Brazil, India, and China. If we do not move decisively, we can expect to add Ethiopia to that list." Founded in 1961, CareCo manufactured personal-care products. Several of its brands enjoyed global recognition. Historically, the company would enter a market through an independent local distributor, which could leverage local knowledge and existing relationships with wholesale traders and retailers to help CareCo establish a foothold in the market. This method had been a low-cost, low- 4 BRIEFCASES | HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL risk way to learn and had been CareCo's practice in most of its Asian, South American, and Eastern European markets. However, CareCo had found that revenue growth using this approach often plateaued quickly due to the local distributor's inexperience or lack of focus. Consequently, CareCo had begun to establish its own subsidiaries, build local manufacturing facilities, and put its own people in charge of growing the local business. Capital expenditures with this approach were much higher, as were the ongoing operating costs of a subsidiary. The results of this shift were not yet clear. If CareCo entered Ethiopia using a local distributor, it would face customs duties of 30% or more. Even with gross margins of 35% to 45%, its product line would be more expensive than were local offerings, and its market share might be reduced by half. The projected costs of this approach were up to $3 million upfront, with a similar annual investment for local marketing. CareCo could also establish a local manufacturing subsidiary. It could charge lower retail prices to compete against existing brands, expand reach, and gain market share while achieving average gross margins of up to 70%. It would have more control of brand image and better government relations, which could help the company battle counterfeit products and brand infringement. CareCo's research indicated high awareness of CareCo's brands among Ethiopian consumers, particularly in Addis Ababa. The market for CareCo products was \$125 million, but Kazuo's team believed that this reflected only purchases by higher-income, urban customers. Kazuo explained, "The market should be much bigger. Incomes are rising fast and discretionary spending is growing. Market growth will be at least 15% in the years to come, and it could be more like 20%." The company was also concerned that a competitor had moved into the market and begun manufacturing locally. Delays could prove costly in the long run, just as they had elsewhere. Kazuo stated, "If we invest in our own facility, we can produce most of our core product portfolio, have a competitive cost position, and price our products the right way. We would ensure quality, manage distribution, branding, and positioning. This is the market opportunity and our chance to get in early." ShoeCo ShoeCo, a footwear manufacturer, had experienced modest success in exporting shoes to Ethiopia through a third-party distributor, and its management team believed it was time to move more aggressively. Beatrice Chen, vice president of global sales, described the strategic decision faced by the company: "The local market offers a significant growth opportunity, and having a factory will give us a cost advantage over other importers, including our Chinese competitors, throughout the region. Founded in China in 1991, ShoeCo produced a wide range of casual and formal leather footwear. Its relentless focus on efficiency had enabled it to bid aggressively on new opportunities and grow quickly. Its early success came through contract manufacturing for U.S. and European brands and providing private-label goods for mass merchandisers and discount shoe retailers. Starting in 2003, ShoeCo also began to develop its own brands for emerging markets. In expanding, ShoeCo had used third-party importers and local manufacturing. A market that could be served by an existing offshore manufacturing facility, preferably in the region, was a candidate for a third-party, import-only strategy, in which ShoeCo usually established a long-term exclusive contract with an independent distributor. If the appropriate conditions for local manufacturing existed, it could choose to establish a local manufacturing facility, either wholly owned or as a joint venture. The case for local manufacturing was strengthened if ShoeCo could profitably export to surrounding countries. HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL | BRIEFCASES In Ethiopia, ShoeCo already imported its shoes through a local distributor. Its experience had given it insight into growth opportunities. The company forecasted approximately $40 million in exports from the proposed factory; the economics of production in Ethiopia meant ShoeCo's existing regional markets, already growing at nearly 10% annually, could be served more profitably this way. ShoeCo's proposal was based on tax incentives and the low cost of inputs. The facility would be built in a special economic zone outside Addis Ababa, which would give ShoeCo at least five years of exemption from corporate taxes. The estimated capital expenditure for the facility was $35 million, with all capital equipment imported duty-free. The company's plant would employ approximately 2,000 local workers when fully operational. At a monthly wage of $50, which would be above the local industry average, ShoeCo's labor costs would still be lower than they were at its other factories. Chen stated, "The key will be to send ShoeCo managers who understand our organizational DNA and who can adjust to the local context to develop the local staff." MedCo In a boardroom in Abu Dhabi, Yousef Al-Abbar, chief operating officer of MedCo, presented his proposal for entry: "It takes $85 million to build a facility. The government has prioritized this sector, so the timing is favorable. We can be operational within twelve months of breaking ground, and we will have a strong base from which to capitalize on the fast-growing spending on health care." Founded in 1983 in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), MedCo manufactured and sold generic pharmaceuticals and over-the-counter medications in select markets in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). MedCo had no proprietary products, but rather offered its own generic brands or private-label goods with localized packaging. The company established manufacturing facilities where it could leverage its strengths in lean, agile manufacturing. MedCo could accommodate relatively small batches and short manufacturing runs with great efficiency, allowing it to serve smaller markets and gain a cost and speed advantage over imported goods. MedCo's management zealously guarded its operational know-how, and entered new markets only with wholly owned manufacturing facilities. The MENA region, excluding the UAE, accounted for 85% of total revenues for MedCo. However, recent growth had slowed, due in part both to the company's business maturing in these markets and to internal turmoil within Syria and Egypt. In contrast, the financial projections for Ethiopia were promising. MedCo's head of sales commented: "The market covered by our portfolio is approximately $200 million, and will grow 15% to 20% annually for the next decade. The average annual spend on health per capita is less than $11 USD, which will increase as the economy grows. 12 Our customers would include the Ministry of Health, which procures for the public health care system, health clinics, and private pharmacies. We want to get in on the ground, learn the market, and build partnerships. MedCo's market research suggested that it would offer a compelling price to potential customers. It had also found that the retail pharmacy channel was fragmented, with more than 3,500 pharmacies, mostly independent, single-store operators. There were nearly 250 wholesalers and importers in the market, many of which worked with large Chinese and Indian manufacturers of generic medicines. 13 MedCo believed that it should enter the market with a wholly owned subsidiary. Initial discussions with the Ethiopia Investment Agency had been promising. Suitable property in an industrial zone near Addis Ababa was available, and MedCo could import capital equipment duty-free and enjoy up to five years of income tax exemption. Al-Abbar commented, "Having our own factory with our own people is our 'secret sauce.' No one else can match our operational efficiency and cost advantage. If we get these elements right, the sales opportunities will be there for the taking." Exhibit 1 Summary of key Ethiopia projections from CareCo, ShoeCo, and MedCo After reading the case, please answer the following two questions, making sure to substantiate your answers with solid arguments and sound reasoning. (1) Summarize the pros and cons of Ethiopia as a potential market based on the following criteria: (a) political environment and industrial policy; (b) Ease of doing business; (c) Market opportunity; (d) Market access; (e) Competitive position; (f) Availability of human capital (NOTE: A good way to address the first question would be to come up with few bullet points for pros and few for cons for each of (a) through (f) above. (2) Please pick any ONE of the three companies you feel most comfortable with (CareCo, MedCo, OR ShoeCo) and utilize the above criteria to answer the following two operational decisions (make sure each decision is properly justified using information in the case and your own reasoning): (a) Should your chosen company market in Ethiopia using a local partner or use its own team? Please justify. (b) Should your chosen company export into Ethiopia using current facilities or build local manufacturing facilities in Ethiopia? Please justify. (PLEASE MAKE SURE TO SPECIFICALLY ANSWER ALL MY QUESTIONS ABOVE AND ORGANIZE YOUR ANSWERS USING MY NUMBERING SCHEME ABOVE (1a; 1b; 1c; 1d; 1e; 1f; 2a; and 2b)Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started