Analyze the balance of payment of Saudi Arabia.

the answer will be based on the article below

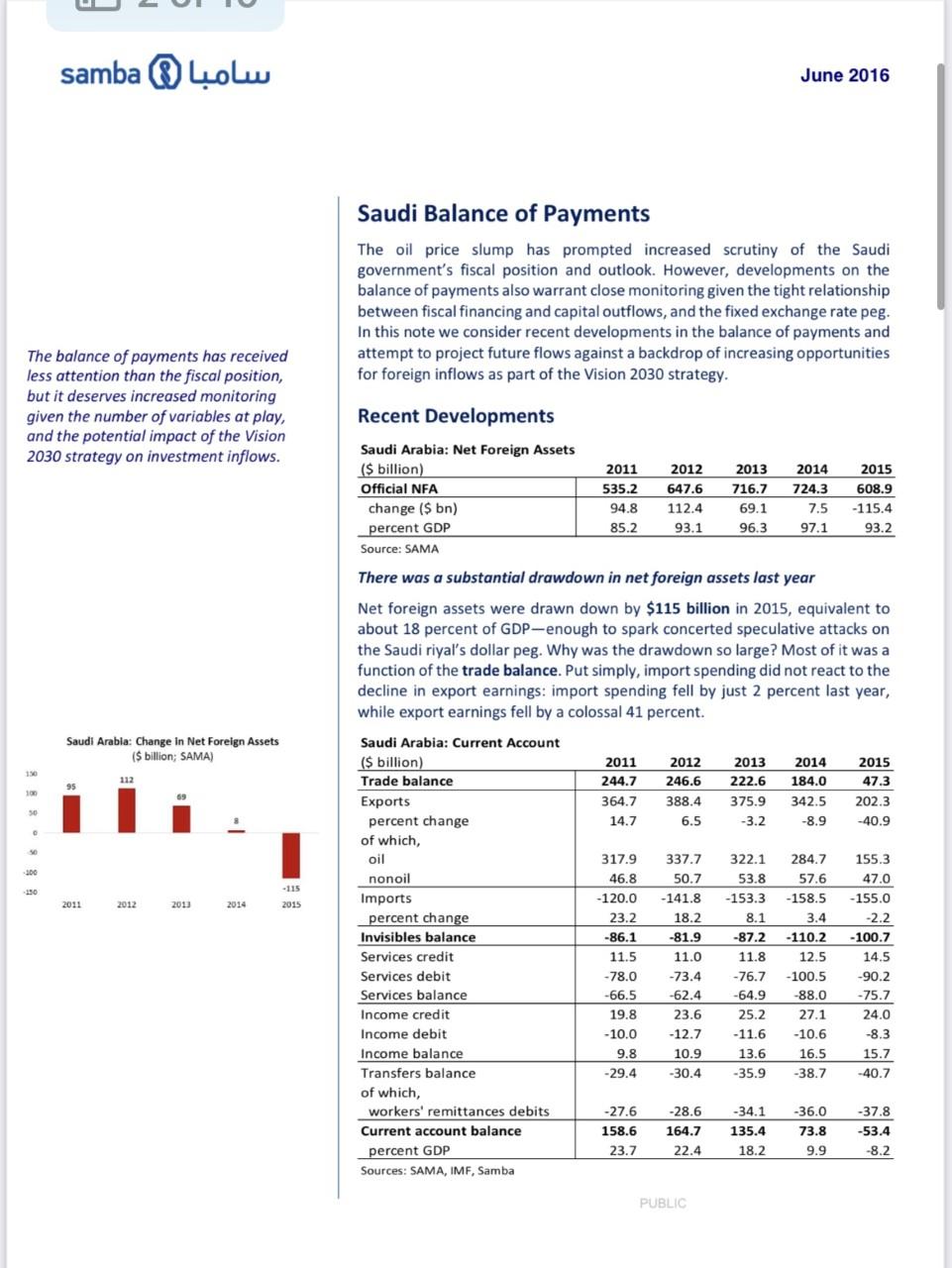

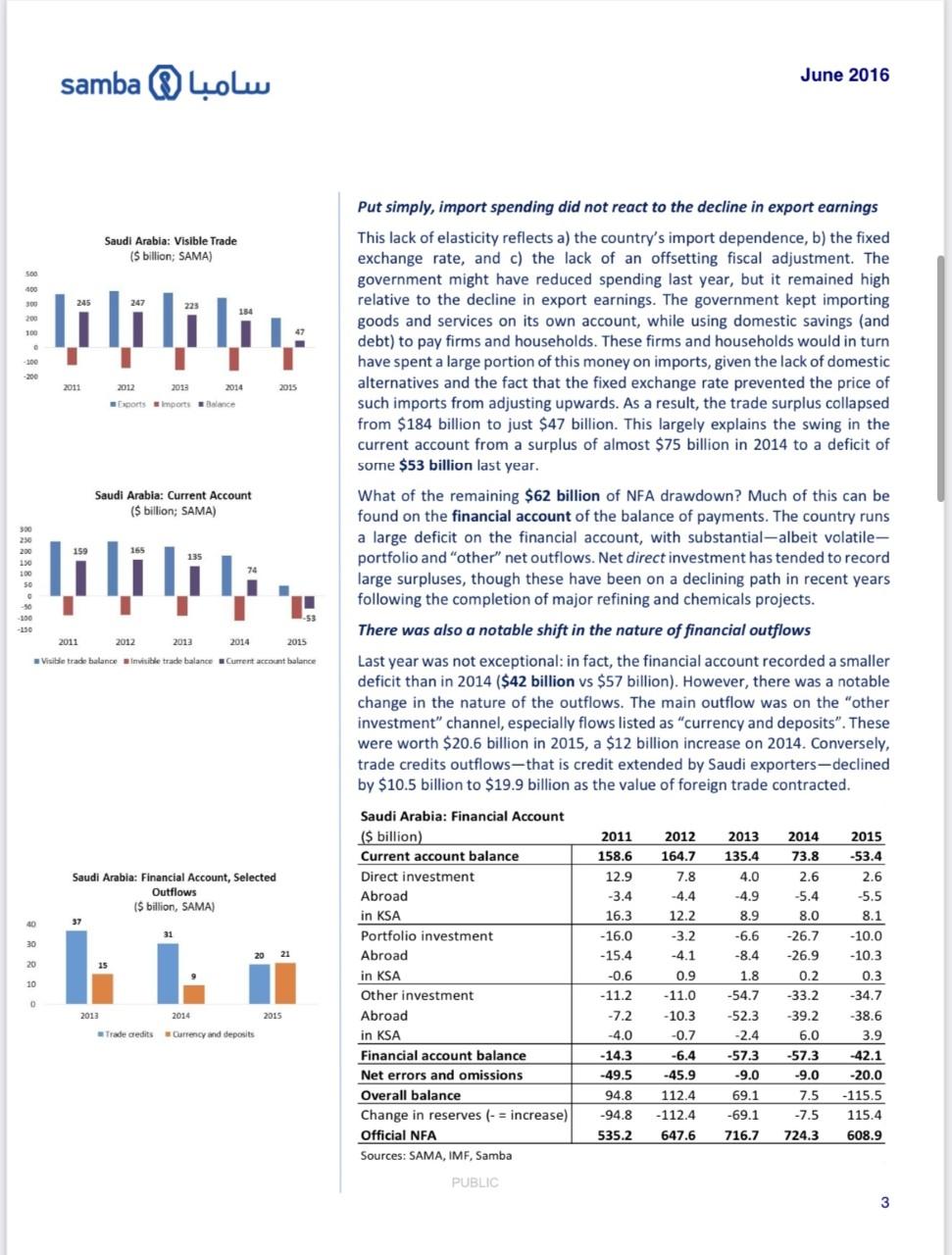

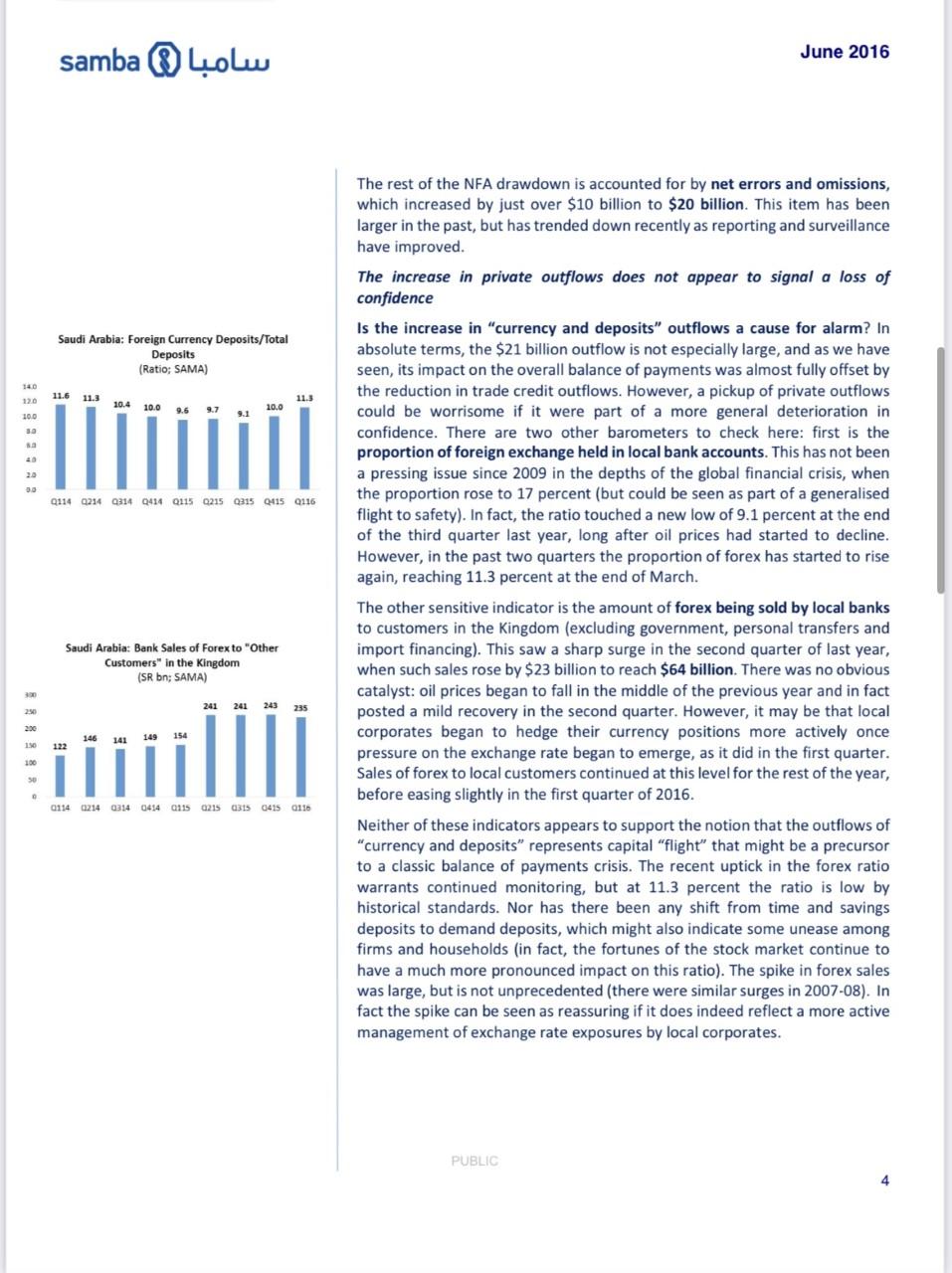

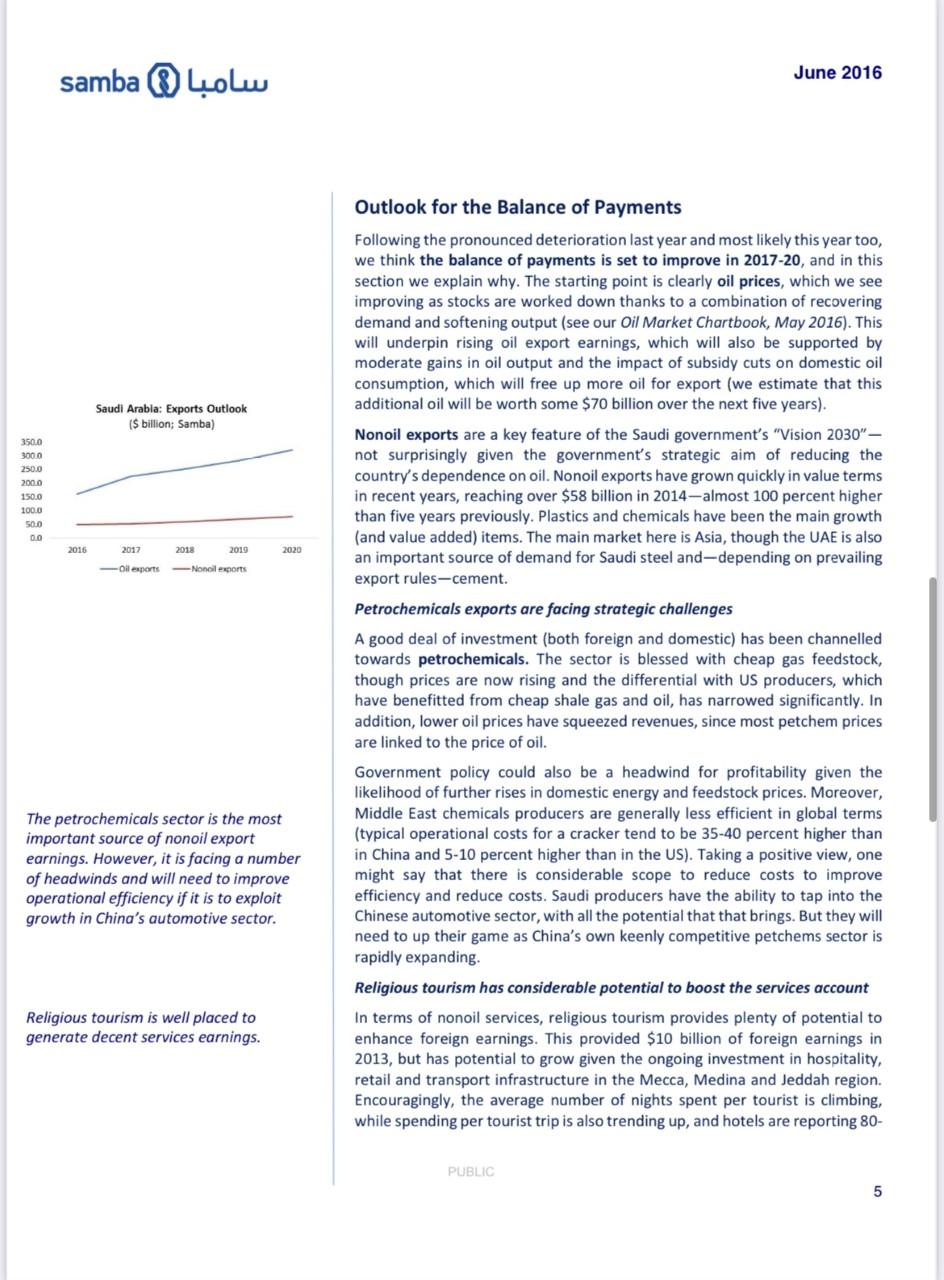

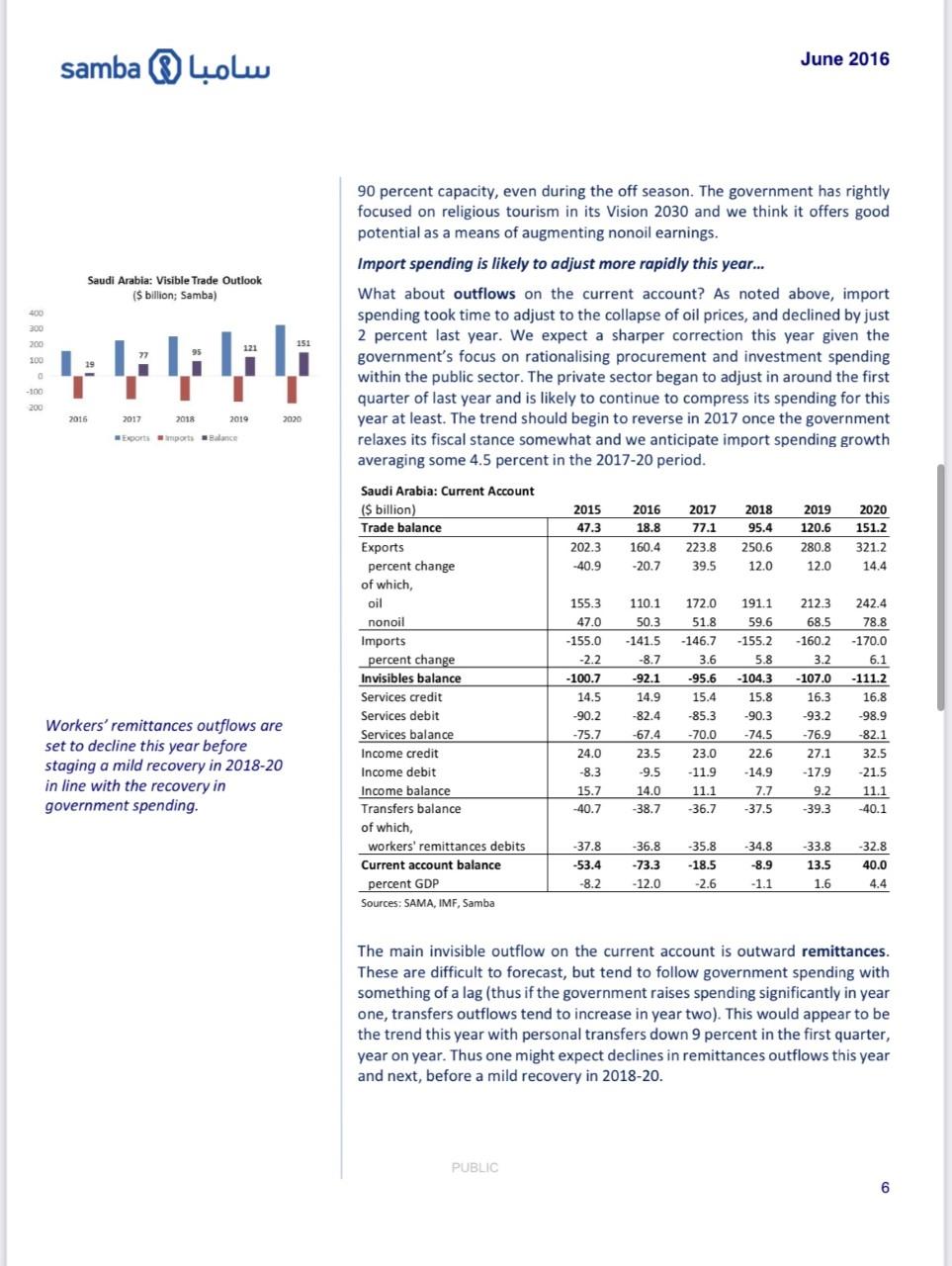

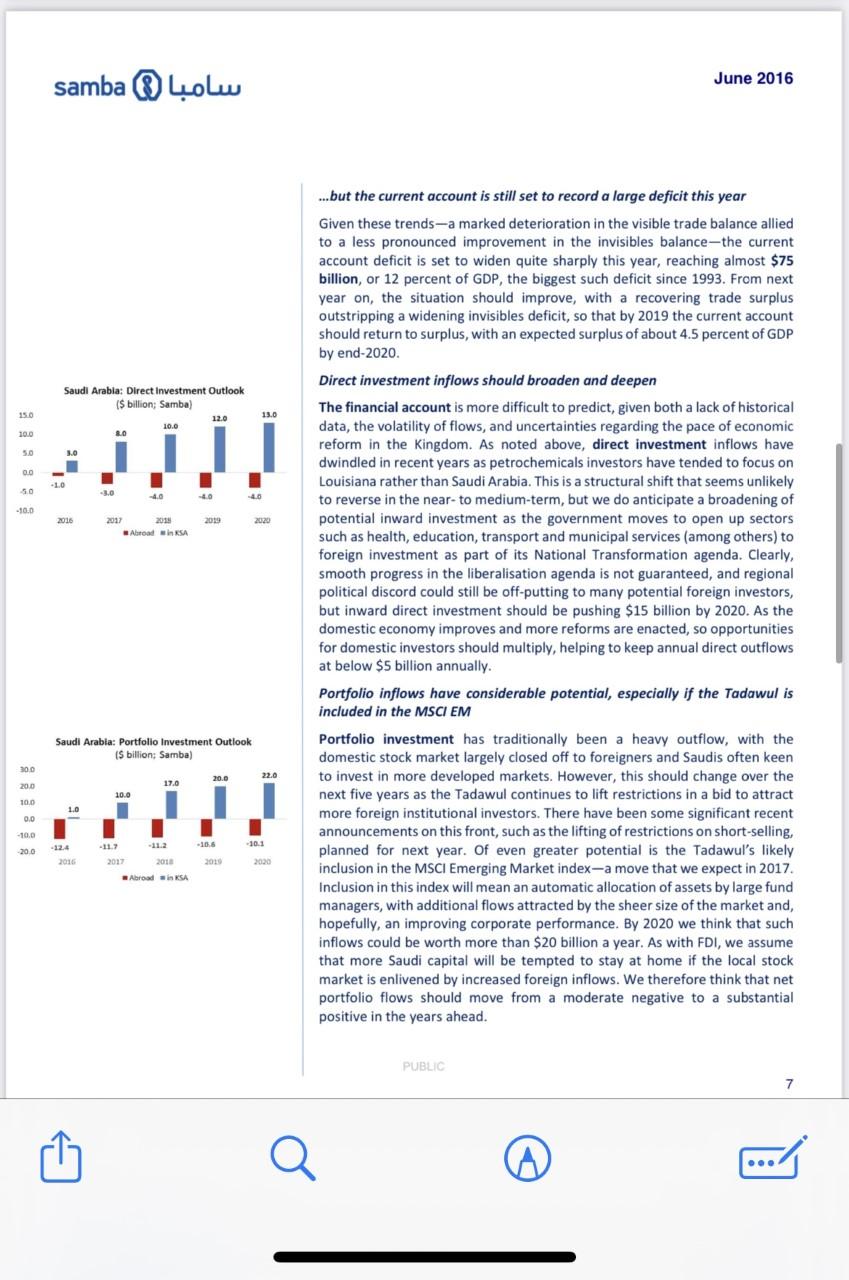

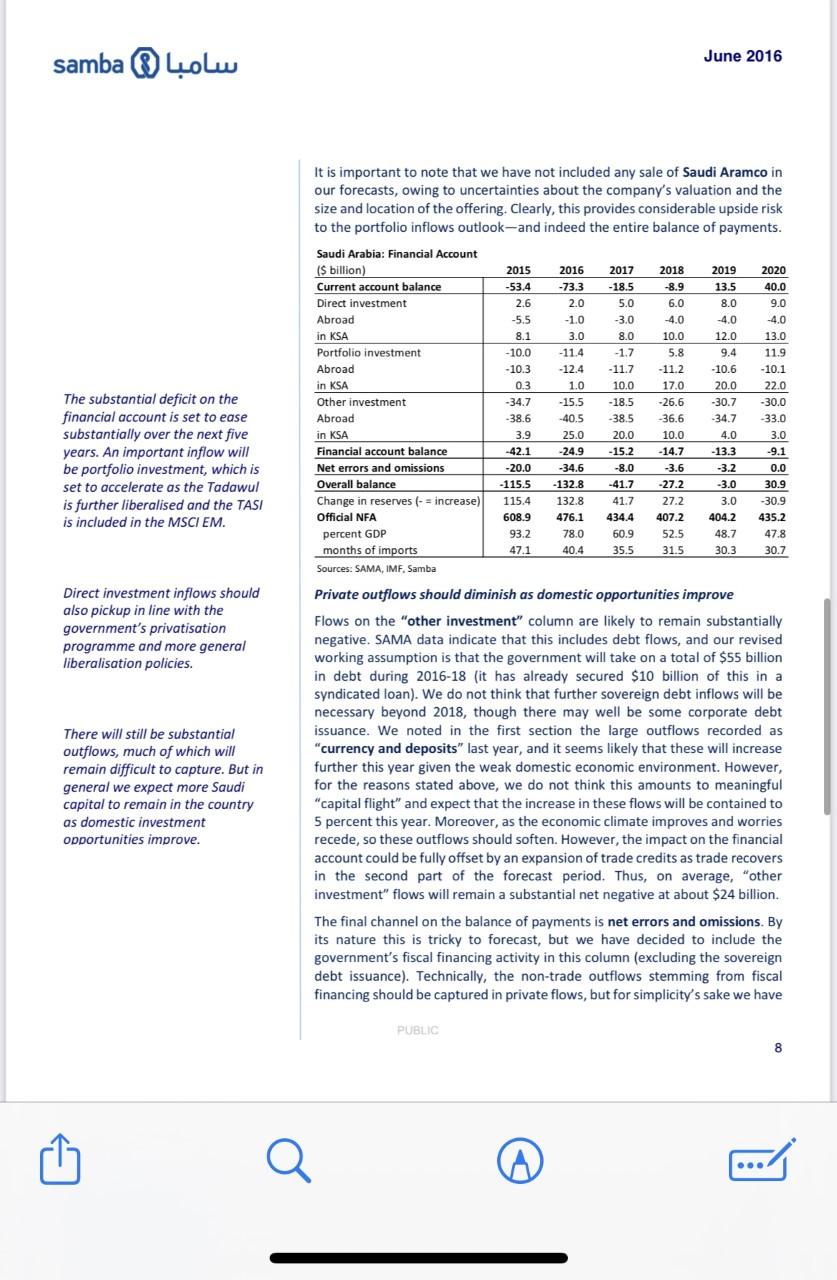

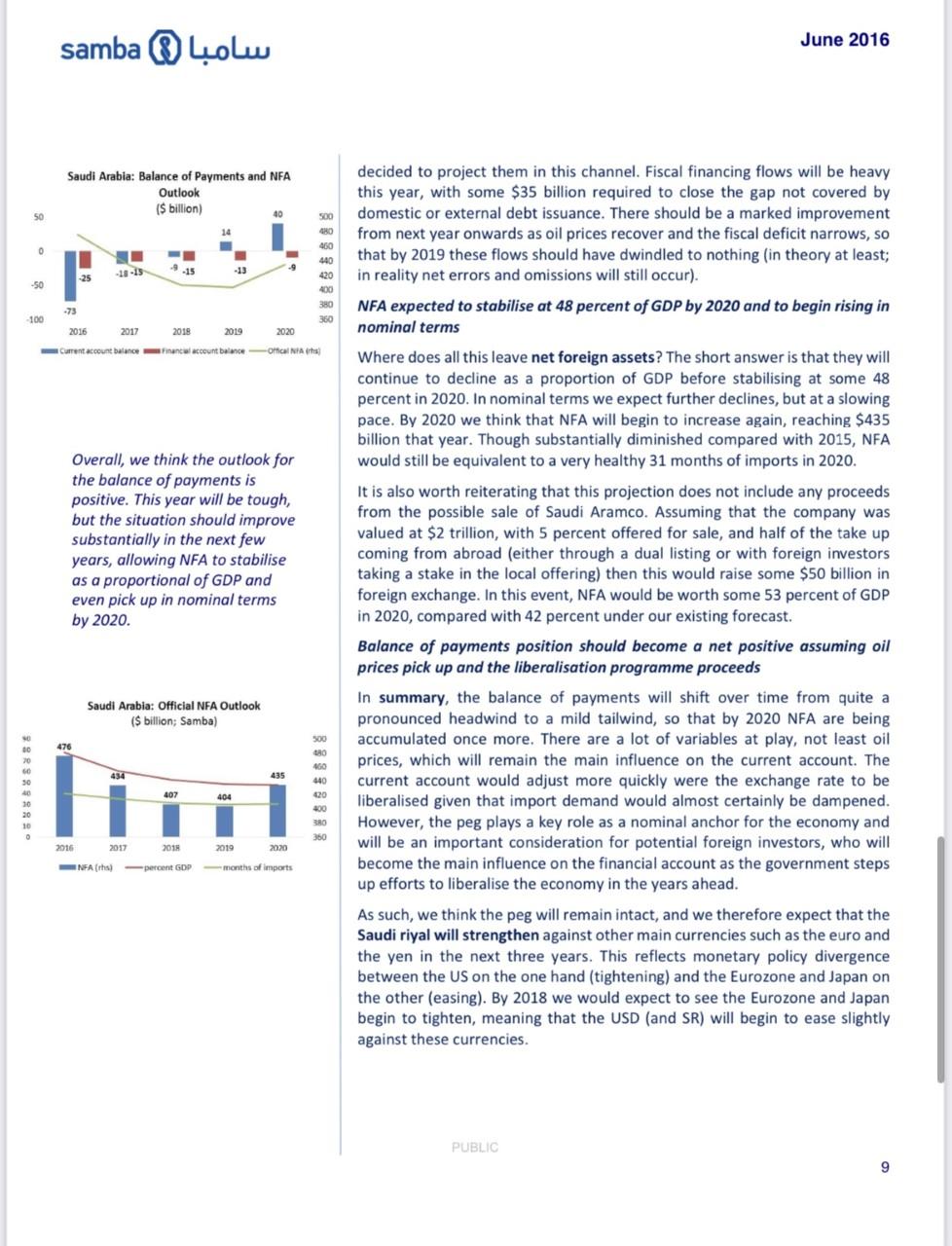

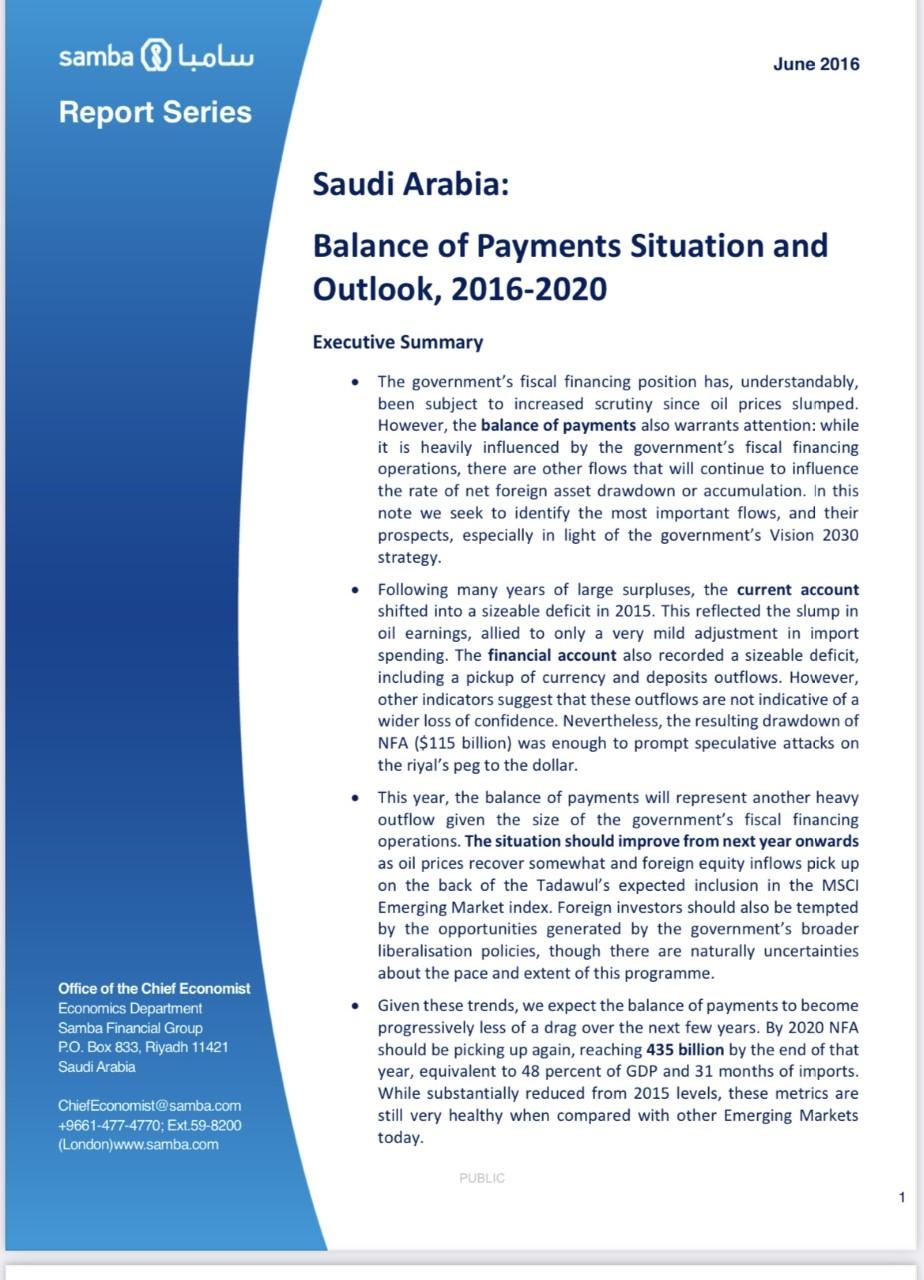

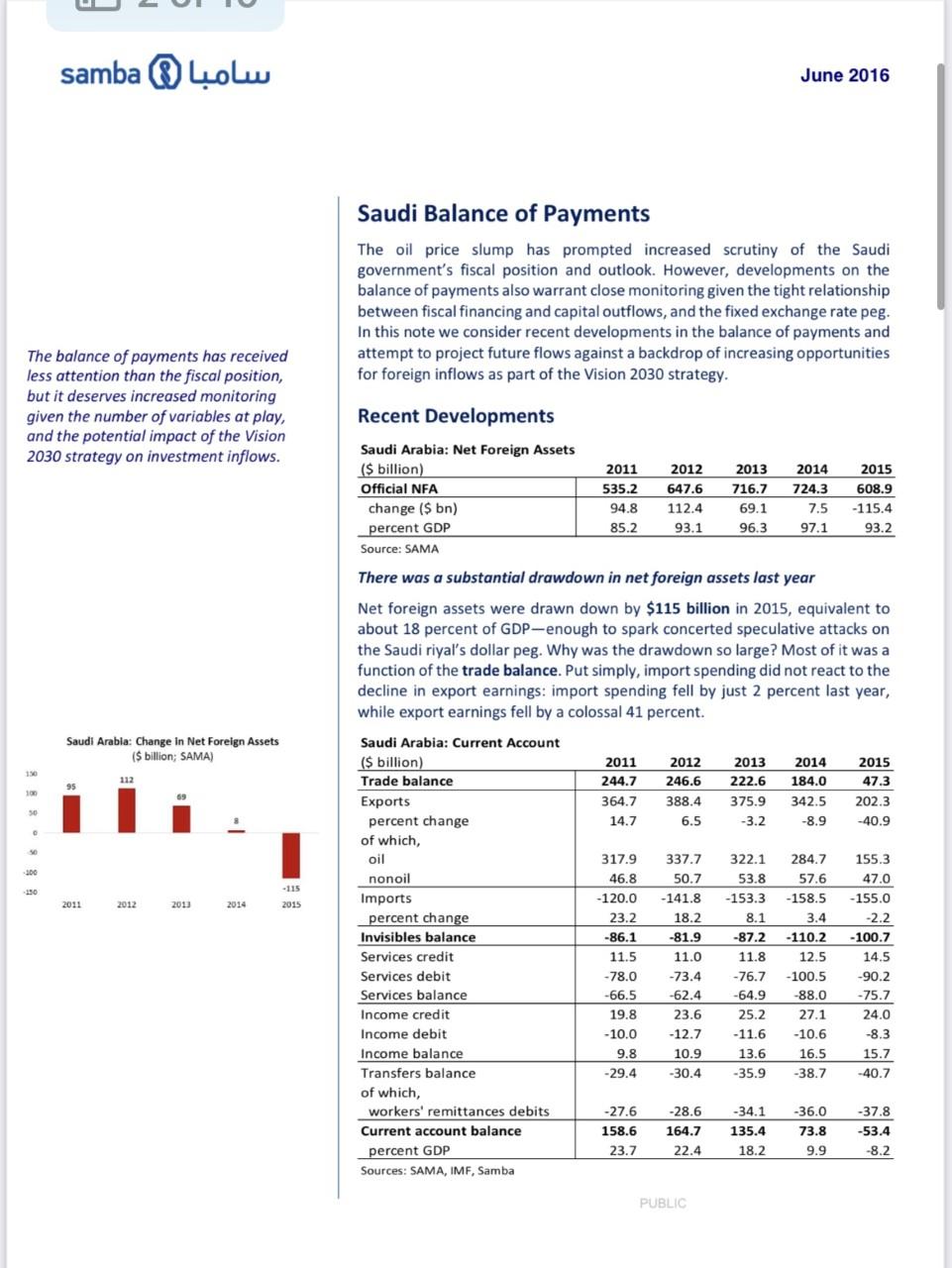

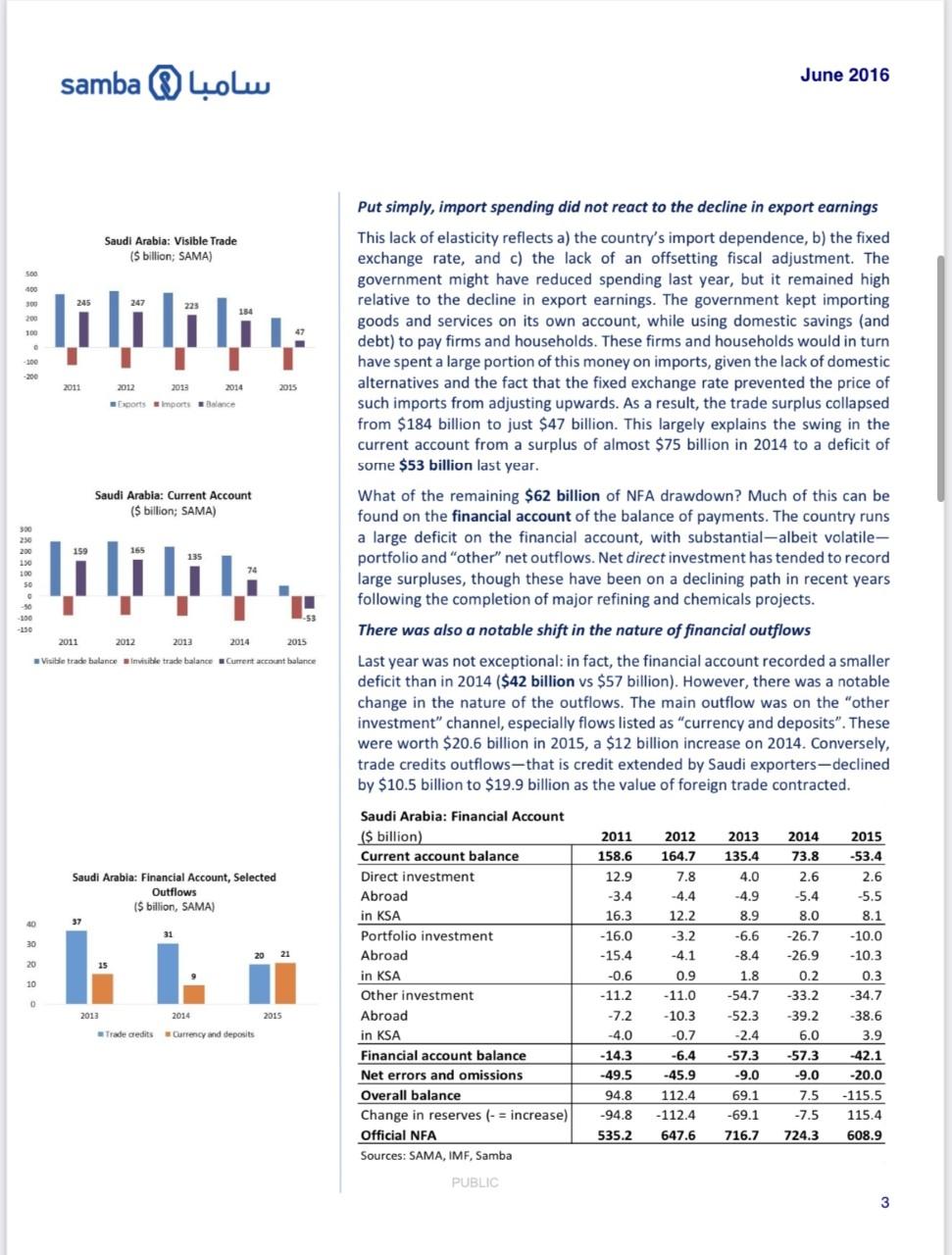

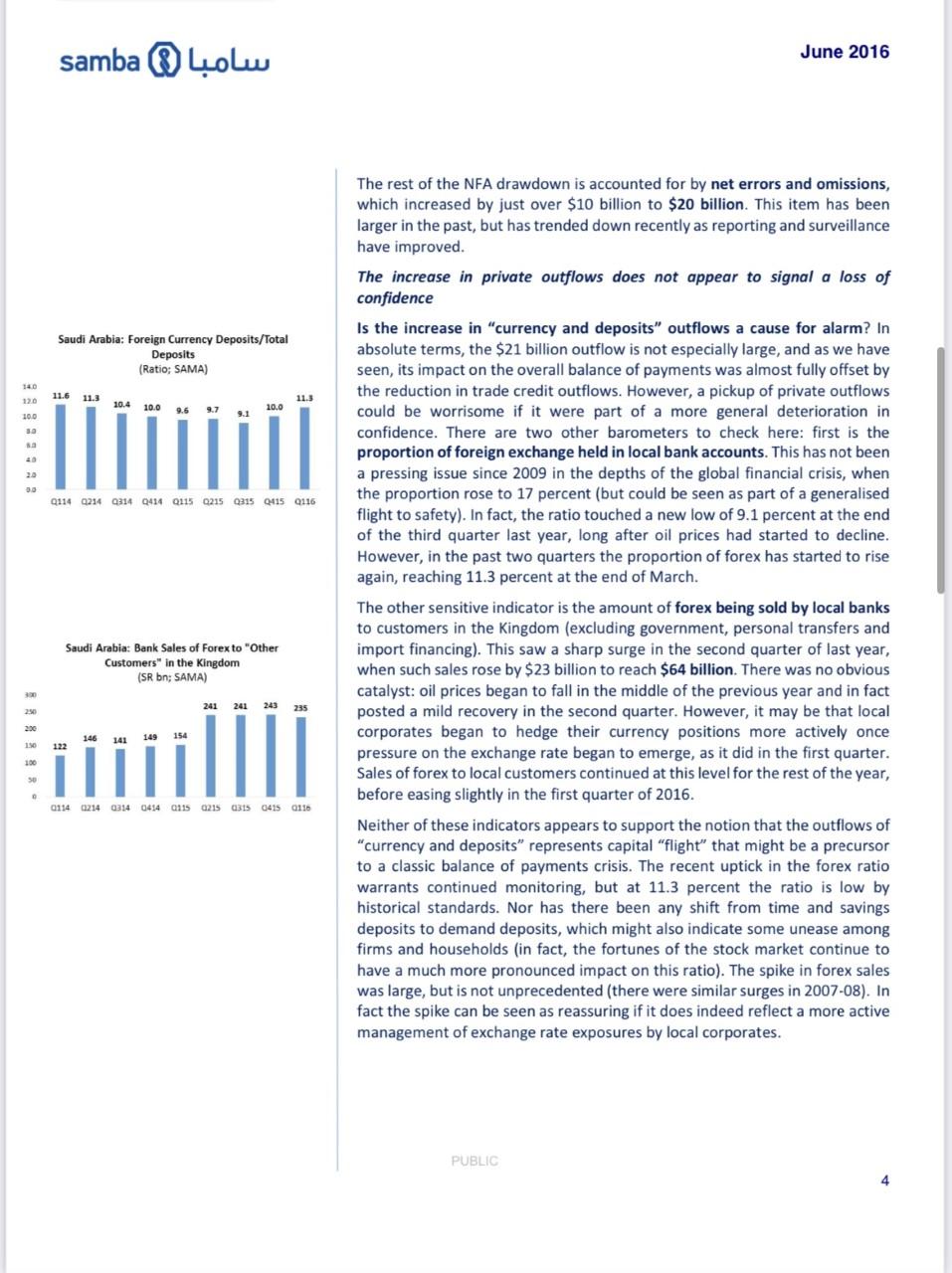

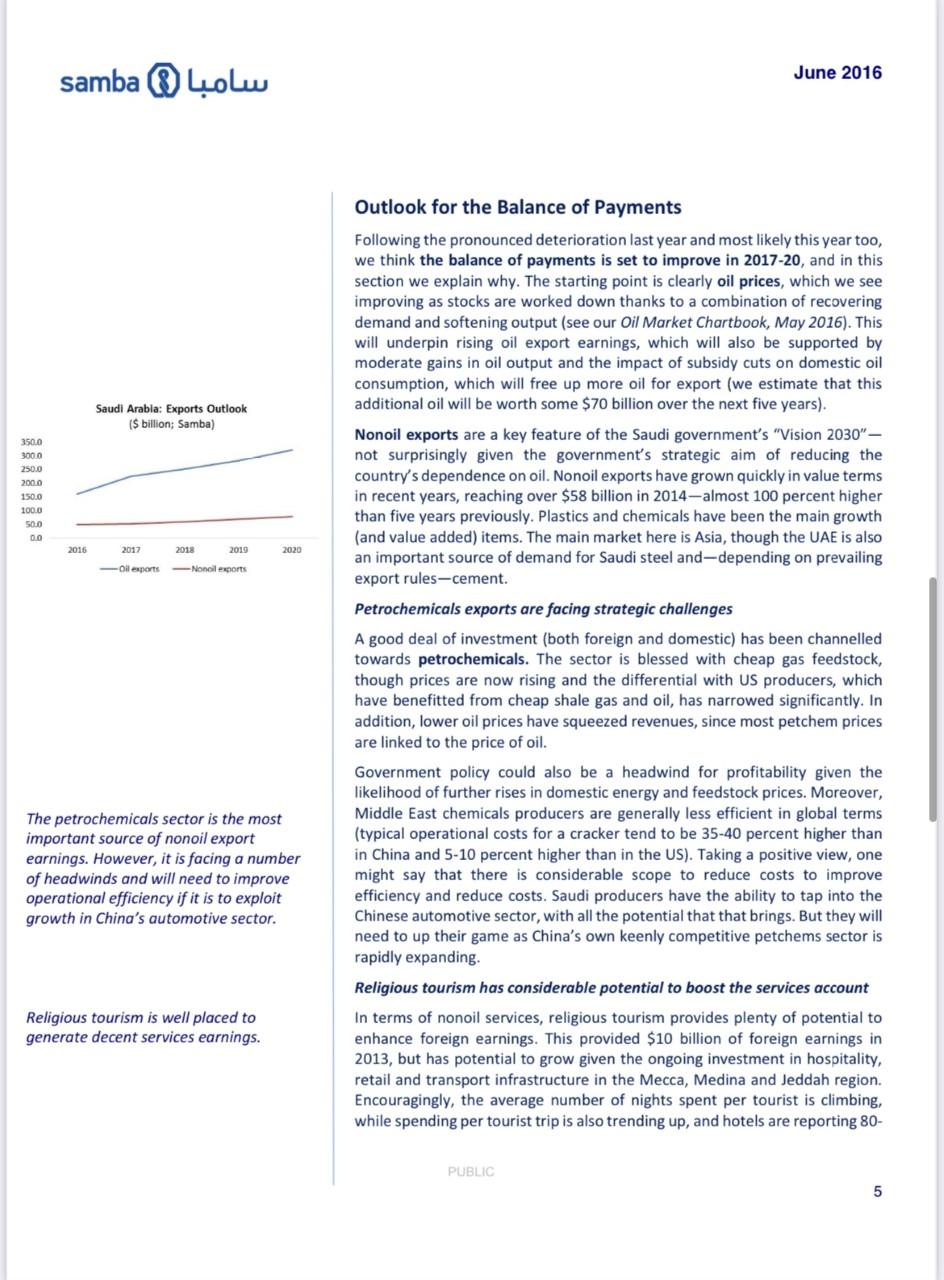

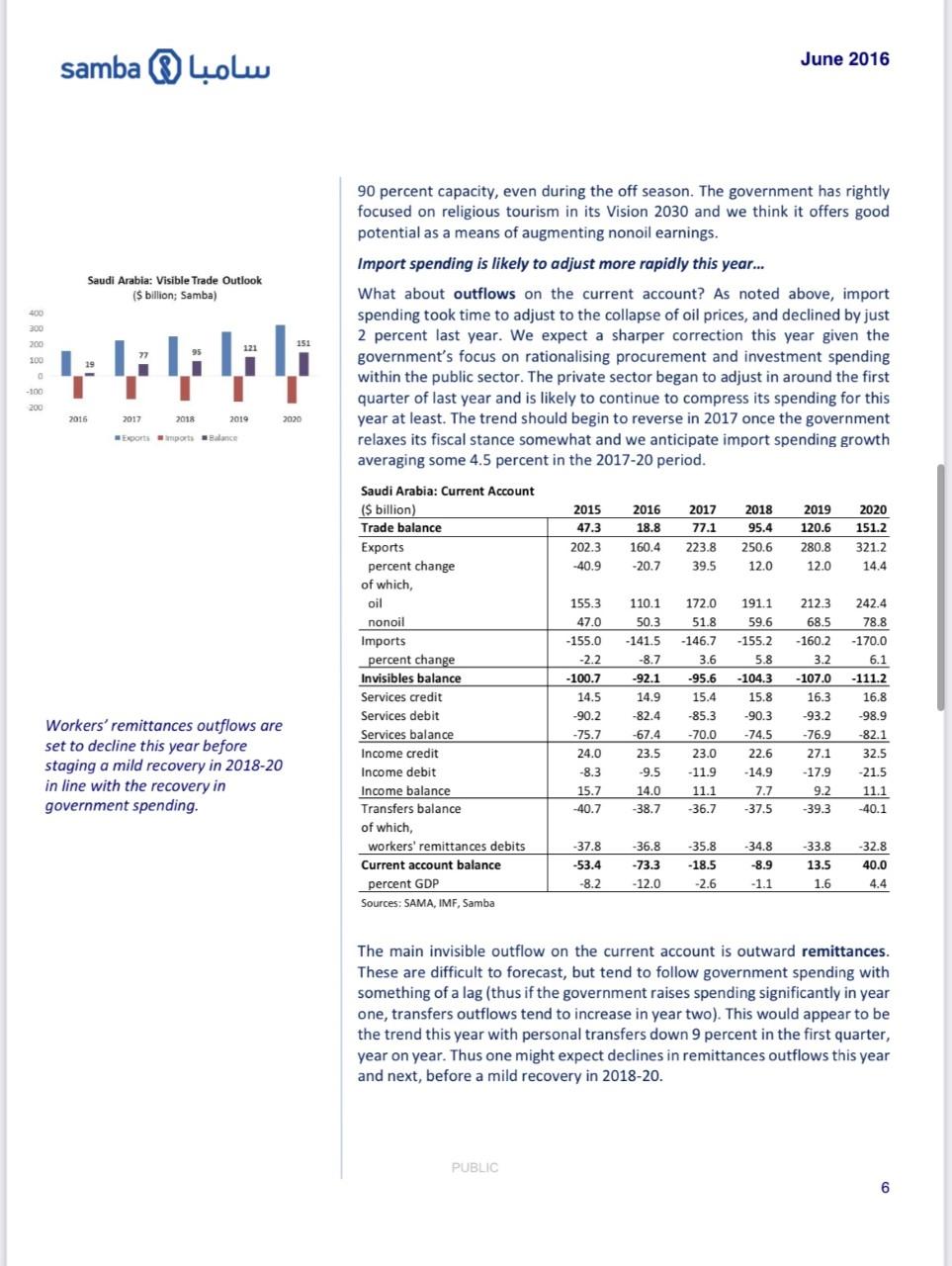

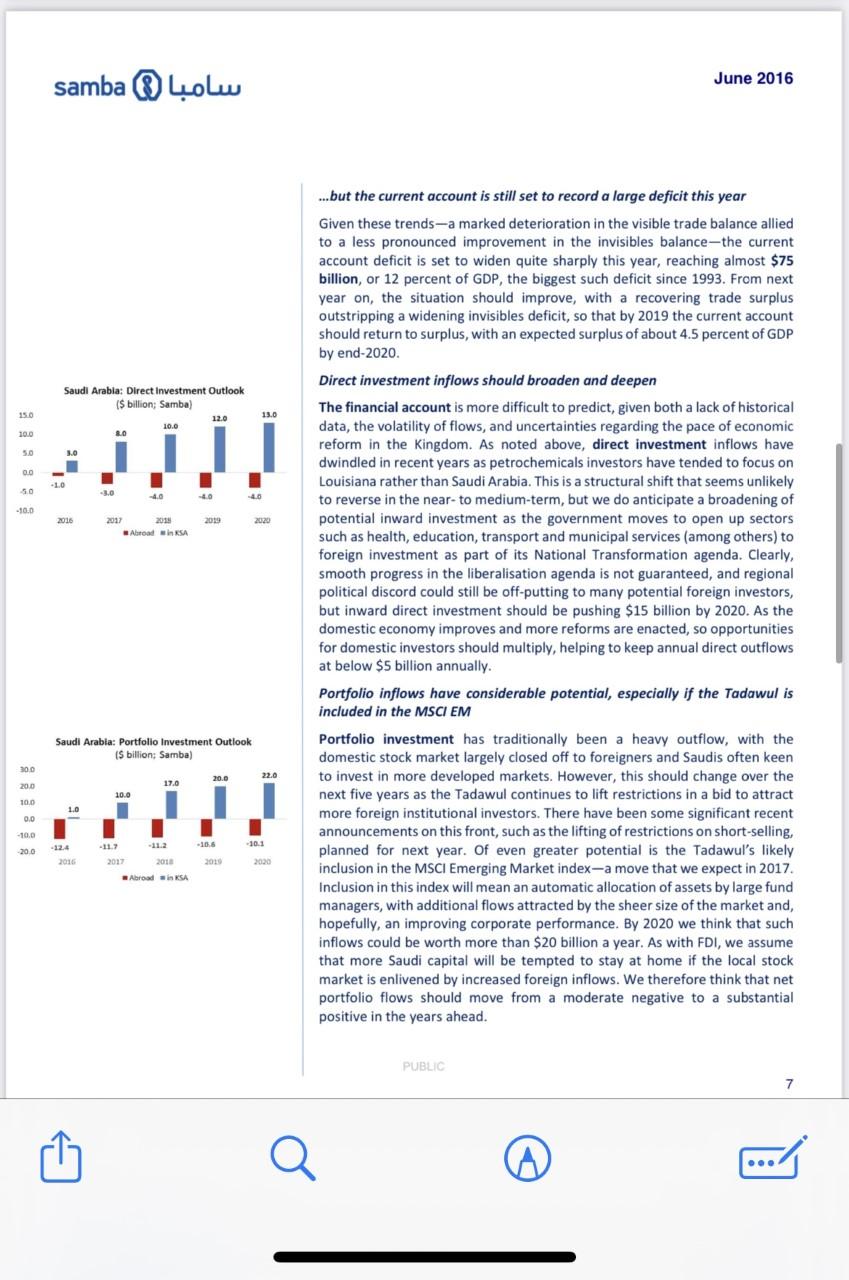

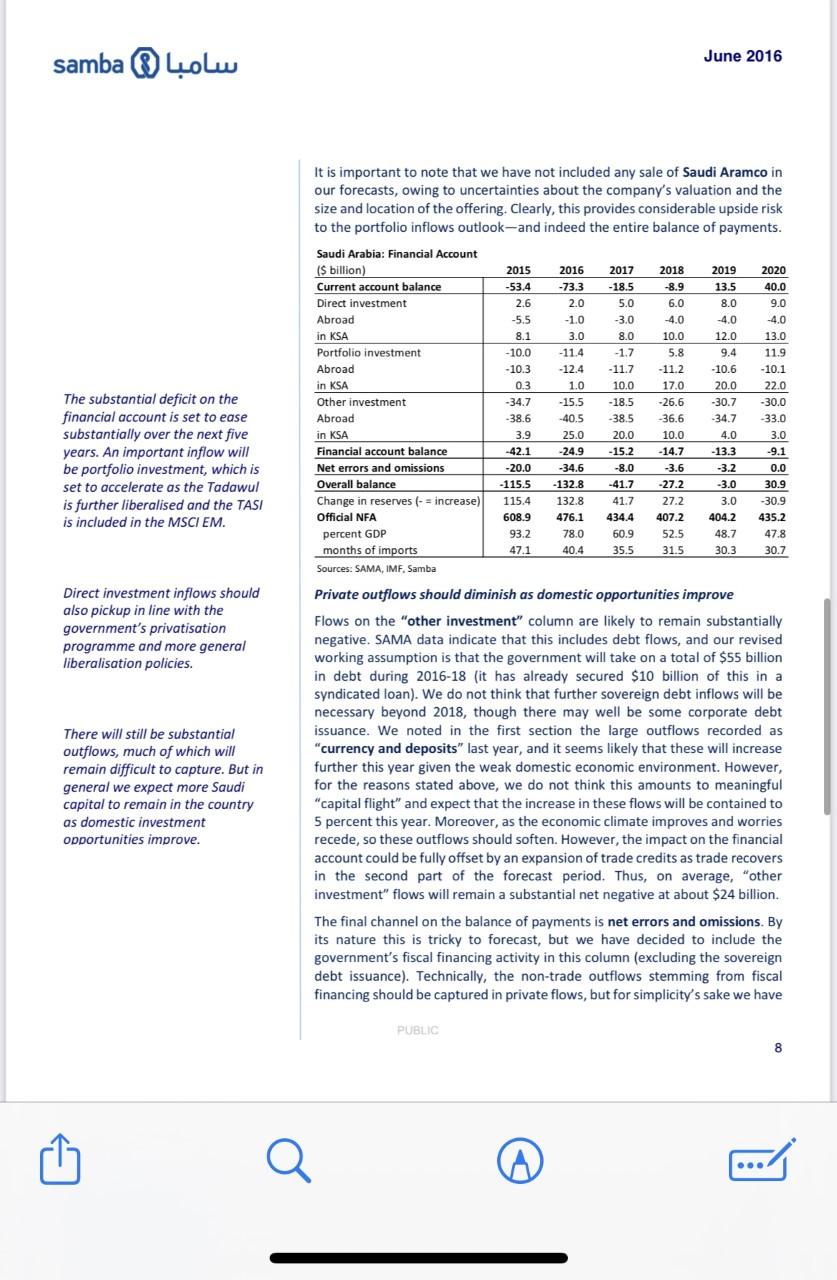

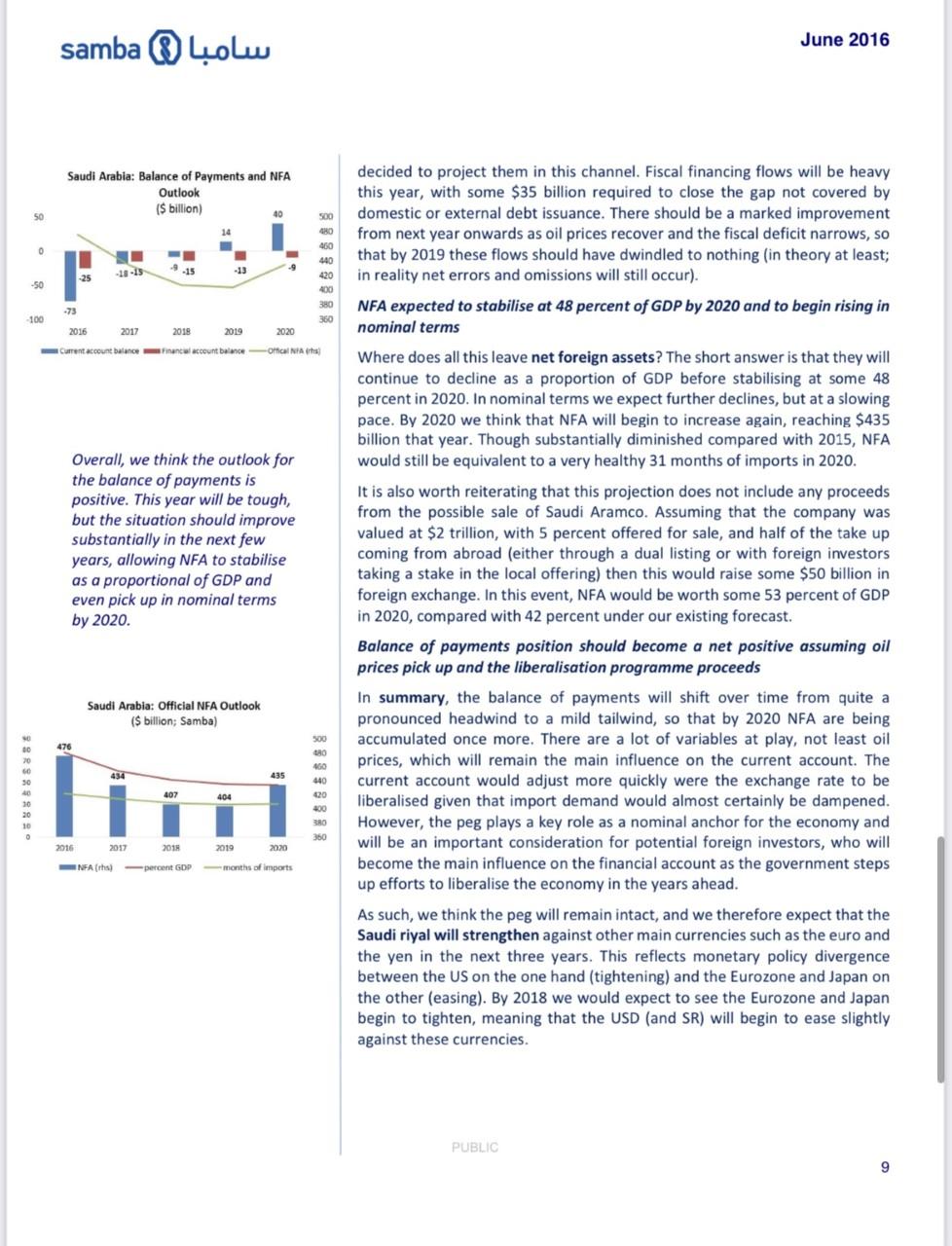

June 2016 Saudi Arabia: Balance of Payments Situation and Outlook, 2016-2020 Executive Summary - The government's fiscal financing position has, understandably, been subject to increased scrutiny since oil prices slumped. However, the balance of payments also warrants attention: while it is heavily influenced by the government's fiscal financing operations, there are other flows that will continue to influence the rate of net foreign asset drawdown or accumulation. In this note we seek to identify the most important flows, and their prospects, especially in light of the government's Vision 2030 strategy. - Following many years of large surpluses, the current account shifted into a sizeable deficit in 2015. This reflected the slump in oil earnings, allied to only a very mild adjustment in import spending. The financial account also recorded a sizeable deficit, including a pickup of currency and deposits outflows. However, other indicators suggest that these outflows are not indicative of a wider loss of confidence. Nevertheless, the resulting drawdown of NFA (\$115 billion) was enough to prompt speculative attacks on the riyal's peg to the dollar. - This year, the balance of payments will represent another heavy outflow given the size of the government's fiscal financing operations. The situation should improve from next year onwards as oil prices recover somewhat and foreign equity inflows pick up on the back of the Tadawul's expected inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Market index. Foreign investors should also be tempted by the opportunities generated by the government's broader liberalisation policies, though there are naturally uncertainties about the pace and extent of this programme. - Given these trends, we expect the balance of payments to become progressively less of a drag over the next few years. By 2020 NFA should be picking up again, reaching 435 billion by the end of that year, equivalent to 48 percent of GDP and 31 months of imports. While substantially reduced from 2015 levels, these metrics are still very healthy when compared with other Emerging Markets today. PUBLIC Saudi Balance of Payments The oil price slump has prompted increased scrutiny of the Saudi government's fiscal position and outlook. However, developments on the balance of payments also warrant close monitoring given the tight relationship between fiscal financing and capital outflows, and the fixed exchange rate peg. In this note we consider recent developments in the balance of payments and The balance of payments has received attempt to project future flows against a backdrop of increasing opportunities less attention than the fiscal position, for foreign inflows as part of the Vision 2030 strategy. but it deserves increased monitoring given the number of variables at play, Recent Developments and the potential impact of the Vision 2030 strategy on investment inflows. Saudi Arabia: Net Foreign Assets There was a substantial drawdown in net foreign assets last year Net foreign assets were drawn down by $115 billion in 2015, equivalent to about 18 percent of GDP-enough to spark concerted speculative attacks on the Saudi riyal's dollar peg. Why was the drawdown so large? Most of it was a function of the trade balance. Put simply, import spending did not react to the decline in export earnings: import spending fell by just 2 percent last year, while export earnings fell by a colossal 41 percent. Saudi Arabla: Change in Net Foreign Assets IS billion: SAMAI Put simply, import spending did not react to the decline in export earnings This lack of elasticity reflects a) the country's import dependence, b) the fixed exchange rate, and c) the lack of an offsetting fiscal adjustment. The government might have reduced spending last year, but it remained high relative to the decline in export earnings. The government kept importing goods and services on its own account, while using domestic savings (and debt) to pay firms and households. These firms and households would in turn have spent a large portion of this money on imports, given the lack of domestic alternatives and the fact that the fixed exchange rate prevented the price of such imports from adjusting upwards. As a result, the trade surplus collapsed from $184 billion to just $47 billion. This largely explains the swing in the current account from a surplus of almost $75 billion in 2014 to a deficit of some $53 billion last year. What of the remaining $62 billion of NFA drawdown? Much of this can be found on the financial account of the balance of payments. The country runs a large deficit on the financial account, with substantial-albeit volatileportfolio and "other" net outflows. Net direct investment has tended to record large surpluses, though these have been on a declining path in recent years following the completion of major refining and chemicals projects. There was also a notable shift in the nature of financial outflows Last year was not exceptional: in fact, the financial account recorded a smaller deficit than in 2014 (\$42 billion vs $57 billion). However, there was a notable change in the nature of the outflows. The main outflow was on the "other investment" channel, especially flows listed as "currency and deposits". These were worth $20.6 billion in 2015, a $12 billion increase on 2014. Conversely, trade credits outflows - that is credit extended by Saudi exporters-declined by $10.5 billion to $19.9 billion as the value of foreign trade contracted. Gaudi Arahia. Cinanrial Arrount The rest of the NFA drawdown is accounted for by net errors and omissions, which increased by just over $10 billion to $20 billion. This item has been larger in the past, but has trended down recently as reporting and surveillance have improved. The increase in private outflows does not appear to signal a loss of confidence Is the increase in "currency and deposits" outflows a cause for alarm? In absolute terms, the $21 billion outflow is not especially large, and as we have seen, its impact on the overall balance of payments was almost fully offset by the reduction in trade credit outflows. However, a pickup of private outflows could be worrisome if it were part of a more general deterioration in confidence. There are two other barometers to check here: first is the proportion of foreign exchange held in local bank accounts. This has not been a pressing issue since 2009 in the depths of the global financial crisis, when the proportion rose to 17 percent (but could be seen as part of a generalised flight to safety). In fact, the ratio touched a new low of 9.1 percent at the end of the third quarter last year, long after oil prices had started to decline. However, in the past two quarters the proportion of forex has started to rise again, reaching 11.3 percent at the end of March. The other sensitive indicator is the amount of forex being sold by local banks to customers in the Kingdom (excluding government, personal transfers and import financing). This saw a sharp surge in the second quarter of last year, when such sales rose by $23 billion to reach $64 billion. There was no obvious catalyst: oil prices began to fall in the middle of the previous year and in fact posted a mild recovery in the second quarter. However, it may be that local corporates began to hedge their currency positions more actively once pressure on the exchange rate began to emerge, as it did in the first quarter. Sales of forex to local customers continued at this level for the rest of the year, before easing slightly in the first quarter of 2016 . Neither of these indicators appears to support the notion that the outflows of "currency and deposits" represents capital "flight" that might be a precursor to a classic balance of payments crisis. The recent uptick in the forex ratio warrants continued monitoring, but at 11.3 percent the ratio is low by historical standards. Nor has there been any shift from time and savings deposits to demand deposits, which might also indicate some unease among firms and households (in fact, the fortunes of the stock market continue to have a much more pronounced impact on this ratio). The spike in forex sales was large, but is not unprecedented (there were similar surges in 2007-08). In fact the spike can be seen as reassuring if it does indeed reflect a more active management of exchange rate exposures by local corporates. Following the pronounced deterioration last year and most likely this year too, we think the balance of payments is set to improve in 2017-20, and in this section we explain why. The starting point is clearly oil prices, which we see improving as stocks are worked down thanks to a combination of recovering demand and softening output (see our Oil Market Chartbook, May 2016). This will underpin rising oil export earnings, which will also be supported by moderate gains in oil output and the impact of subsidy cuts on domestic oil consumption, which will free up more oil for export (we estimate that this additional oil will be worth some $70 billion over the next five years). Nonoil exports are a key feature of the Saudi government's "Vision 2030" not surprisingly given the government's strategic aim of reducing the country's dependence on oil. Nonoil exports have grown quickly in value terms in recent years, reaching over $58 billion in 2014-almost 100 percent higher than five years previously. Plastics and chemicals have been the main growth (and value added) items. The main market here is Asia, though the UAE is also an important source of demand for Saudi steel and-depending on prevailing export rules-cement. Petrochemicals exports are facing strategic challenges A good deal of investment (both foreign and domestic) has been channelled towards petrochemicals. The sector is blessed with cheap gas feedstock, though prices are now rising and the differential with US producers, which have benefitted from cheap shale gas and oil, has narrowed significantly. In addition, lower oil prices have squeezed revenues, since most petchem prices are linked to the price of oil. Government policy could also be a headwind for profitability given the likelihood of further rises in domestic energy and feedstock prices. Moreover, Middle East chemicals producers are generally less efficient in global terms (typical operational costs for a cracker tend to be 35-40 percent higher than in China and 5-10 percent higher than in the US). Taking a positive view, one might say that there is considerable scope to reduce costs to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Saudi producers have the ability to tap into the Chinese automotive sector, with all the potential that that brings. But they will need to up their game as China's own keenly competitive petchems sector is rapidly expanding. Religious tourism has considerable potential to boost the services account Religious tourism is well placed to In terms of nonoil services, religious tourism provides plenty of potential to enhance foreign earnings. This provided $10 billion of foreign earnings in 2013 , but has potential to grow given the ongoing investment in hospitality, retail and transport infrastructure in the Mecca, Medina and Jeddah region. Encouragingly, the average number of nights spent per tourist is climbing, while spending per tourist trip is also trending up, and hotels are reporting 80 - 90 percent capacity, even during the off season. The government has rightly focused on religious tourism in its Vision 2030 and we think it offers good potential as a means of augmenting nonoil earnings. Import spending is likely to adjust more rapidly this year... What about outflows on the current account? As noted above, import spending took time to adjust to the collapse of oil prices, and declined by just 2 percent last year. We expect a sharper correction this year given the government's focus on rationalising procurement and investment spending within the public sector. The private sector began to adjust in around the first quarter of last year and is likely to continue to compress its spending for this year at least. The trend should begin to reverse in 2017 once the government relaxes its fiscal stance somewhat and we anticipate import spending growth averaging some 4.5 percent in the 201720 period. Workers' remittances outflows are set to decline this year before staging a mild recovery in 2018-20 in line with the recovery in government spending. The main invisible outflow on the current account is outward remittances. These are difficult to forecast, but tend to follow government spending with something of a lag (thus if the government raises spending significantly in year one, transfers outflows tend to increase in year two). This would appear to be the trend this year with personal transfers down 9 percent in the first quarter, year on year. Thus one might expect declines in remittances outflows this year and next, before a mild recovery in 2018-20. ...but the current account is still set to record a large deficit this year Given these trends-a marked deterioration in the visible trade balance allied to a less pronounced improvement in the invisibles balance-the current account deficit is set to widen quite sharply this year, reaching almost $75 billion, or 12 percent of GDP, the biggest such deficit since 1993. From next year on, the situation should improve, with a recovering trade surplus outstripping a widening invisibles deficit, so that by 2019 the current account should return to surplus, with an expected surplus of about 4.5 percent of GDP by end-2020. Direct investment inflows should broaden and deepen The financial account is more difficult to predict, given both a lack of historical data, the volatility of flows, and uncertainties regarding the pace of economic reform in the Kingdom. As noted above, direct investment inflows have dwindled in recent years as petrochemicals investors have tended to focus on Louisiana rather than Saudi Arabia. This is a structural shift that seems unlikely to reverse in the near- to medium-term, but we do anticipate a broadening of potential inward investment as the government moves to open up sectors such as health, education, transport and municipal services (among others) to foreign investment as part of its National Transformation agenda. Clearly, smooth progress in the liberalisation agenda is not guaranteed, and regional political discord could still be off-putting to many potential foreign investors, but inward direct investment should be pushing $15 billion by 2020. As the domestic economy improves and more reforms are enacted, so opportunities for domestic investors should multiply, helping to keep annual direct outflows at below $5 billion annually. Portfolio inflows have considerable potential, especially if the Tadawul is included in the MSCI EM Portfolio investment has traditionally been a heavy outflow, with the domestic stock market largely closed off to foreigners and Saudis often keen to invest in more developed markets. However, this should change over the next five years as the Tadawul continues to lift restrictions in a bid to attract more foreign institutional investors. There have been some significant recent announcements on this front, such as the lifting of restrictions on short-selling, planned for next year. Of even greater potential is the Tadawul's likely inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Market index-a move that we expect in 2017. Inclusion in this index will mean an automatic allocation of assets by large fund managers, with additional flows attracted by the sheer size of the market and, hopefully, an improving corporate performance. By 2020 we think that such inflows could be worth more than $20 billion a year. As with FDI, we assume that more Saudi capital will be tempted to stay at home if the local stock market is enlivened by increased foreign inflows. We therefore think that net portfolio flows should move from a moderate negative to a substantial positive in the years ahead. It is important to note that we have not included any sale of Saudi Aramco in our forecasts, owing to uncertainties about the company's valuation and the size and location of the offering. Clearly, this provides considerable upside risk to the portfolio inflows outlook-and indeed the entire balance of payments. The substantial deficit on the financial account is set to ease substantially over the next five years. An important inflow will be portfolio investment, which is set to accelerate as the Tadawul is further liberalised and the TASI is included in the MSCI EM. Direct investment inflows should Private outflows should diminish as domestic opportunities improve also pickup in line with the government's privatisation Flows on the "other investment" column are likely to remain substantially programme and more general negative. SAMA data indicate that this includes debt flows, and our revised liberalisation policies. working assumption is that the government will take on a total of $55 billion in debt during 2016-18 (it has already secured $10 billion of this in a syndicated loan). We do not think that further sovereign debt inflows will be necessary beyond 2018 , though there may well be some corporate debt There will still be substantial issuance. We noted in the first section the large outflows recorded as general we expect more Saudi for the reasons stated above, we do not think this amounts to meaningful capital to remain in the country "capital flight" and expect that the increase in these flows will be contained to as domestic investment 5 percent this year. Moreover, as the economic climate improves and worries opportunities improve. recede, so these outflows should soften. However, the impact on the financial account could be fully offset by an expansion of trade credits as trade recovers in the second part of the forecast period. Thus, on average, "other investment" flows will remain a substantial net negative at about $24 billion. The final channel on the balance of payments is net errors and omissions. By its nature this is tricky to forecast, but we have decided to include the government's fiscal financing activity in this column (excluding the sovereign debt issuance). Technically, the non-trade outflows stemming from fiscal financing should be captured in private flows, but for simplicity's sake we have decided to project them in this channel. Fiscal financing flows will be heavy this year, with some $35 billion required to close the gap not covered by domestic or external debt issuance. There should be a marked improvement from next year onwards as oil prices recover and the fiscal deficit narrows, so that by 2019 these flows should have dwindled to nothing (in theory at least; in reality net errors and omissions will still occur). NFA expected to stabilise at 48 percent of GDP by 2020 and to begin rising in nominal terms Where does all this leave net foreign assets? The short answer is that they will continue to decline as a proportion of GDP before stabilising at some 48 percent in 2020. In nominal terms we expect further declines, but at a slowing pace. By 2020 we think that NFA will begin to increase again, reaching $435 billion that year. Though substantially diminished compared with 2015, NFA Overall, we think the outlook for would still be equivalent to a very healthy 31 months of imports in 2020. the balance of payments is positive. This year will be tough, It is also worth reiterating that this projection does not include any proceeds but the situation should improve from the possible sale of Saudi Aramco. Assuming that the company was substantially in the next few valued at $2 trillion, with 5 percent offered for sale, and half of the take up years, allowing NFA to stabilise coming from abroad (either through a dual listing or with foreign investors as a proportional of GDP and taking a stake in the local offering) then this would raise some $50 billion in even pick up in nominal terms foreign exchange. In this event, NFA would be worth some 53 percent of GDP by 2020. in 2020 , compared with 42 percent under our existing forecast. Balance of payments position should become a net positive assuming oil prices pick up and the liberalisation programme proceeds In summary, the balance of payments will shift over time from quite a pronounced headwind to a mild tailwind, so that by 2020 NFA are being accumulated once more. There are a lot of variables at play, not least oil prices, which will remain the main influence on the current account. The current account would adjust more quickly were the exchange rate to be liberalised given that import demand would almost certainly be dampened. However, the peg plays a key role as a nominal anchor for the economy and will be an important consideration for potential foreign investors, who will become the main influence on the financial account as the government steps up efforts to liberalise the economy in the years ahead. As such, we think the peg will remain intact, and we therefore expect that the Saudi riyal will strengthen against other main currencies such as the euro and the yen in the next three years. This reflects monetary policy divergence between the US on the one hand (tightening) and the Eurozone and Japan on the other (easing). By 2018 we would expect to see the Eurozone and Japan begin to tighten, meaning that the USD (and SR) will begin to ease slightly against these currencies. June 2016 Saudi Arabia: Balance of Payments Situation and Outlook, 2016-2020 Executive Summary - The government's fiscal financing position has, understandably, been subject to increased scrutiny since oil prices slumped. However, the balance of payments also warrants attention: while it is heavily influenced by the government's fiscal financing operations, there are other flows that will continue to influence the rate of net foreign asset drawdown or accumulation. In this note we seek to identify the most important flows, and their prospects, especially in light of the government's Vision 2030 strategy. - Following many years of large surpluses, the current account shifted into a sizeable deficit in 2015. This reflected the slump in oil earnings, allied to only a very mild adjustment in import spending. The financial account also recorded a sizeable deficit, including a pickup of currency and deposits outflows. However, other indicators suggest that these outflows are not indicative of a wider loss of confidence. Nevertheless, the resulting drawdown of NFA (\$115 billion) was enough to prompt speculative attacks on the riyal's peg to the dollar. - This year, the balance of payments will represent another heavy outflow given the size of the government's fiscal financing operations. The situation should improve from next year onwards as oil prices recover somewhat and foreign equity inflows pick up on the back of the Tadawul's expected inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Market index. Foreign investors should also be tempted by the opportunities generated by the government's broader liberalisation policies, though there are naturally uncertainties about the pace and extent of this programme. - Given these trends, we expect the balance of payments to become progressively less of a drag over the next few years. By 2020 NFA should be picking up again, reaching 435 billion by the end of that year, equivalent to 48 percent of GDP and 31 months of imports. While substantially reduced from 2015 levels, these metrics are still very healthy when compared with other Emerging Markets today. PUBLIC Saudi Balance of Payments The oil price slump has prompted increased scrutiny of the Saudi government's fiscal position and outlook. However, developments on the balance of payments also warrant close monitoring given the tight relationship between fiscal financing and capital outflows, and the fixed exchange rate peg. In this note we consider recent developments in the balance of payments and The balance of payments has received attempt to project future flows against a backdrop of increasing opportunities less attention than the fiscal position, for foreign inflows as part of the Vision 2030 strategy. but it deserves increased monitoring given the number of variables at play, Recent Developments and the potential impact of the Vision 2030 strategy on investment inflows. Saudi Arabia: Net Foreign Assets There was a substantial drawdown in net foreign assets last year Net foreign assets were drawn down by $115 billion in 2015, equivalent to about 18 percent of GDP-enough to spark concerted speculative attacks on the Saudi riyal's dollar peg. Why was the drawdown so large? Most of it was a function of the trade balance. Put simply, import spending did not react to the decline in export earnings: import spending fell by just 2 percent last year, while export earnings fell by a colossal 41 percent. Saudi Arabla: Change in Net Foreign Assets IS billion: SAMAI Put simply, import spending did not react to the decline in export earnings This lack of elasticity reflects a) the country's import dependence, b) the fixed exchange rate, and c) the lack of an offsetting fiscal adjustment. The government might have reduced spending last year, but it remained high relative to the decline in export earnings. The government kept importing goods and services on its own account, while using domestic savings (and debt) to pay firms and households. These firms and households would in turn have spent a large portion of this money on imports, given the lack of domestic alternatives and the fact that the fixed exchange rate prevented the price of such imports from adjusting upwards. As a result, the trade surplus collapsed from $184 billion to just $47 billion. This largely explains the swing in the current account from a surplus of almost $75 billion in 2014 to a deficit of some $53 billion last year. What of the remaining $62 billion of NFA drawdown? Much of this can be found on the financial account of the balance of payments. The country runs a large deficit on the financial account, with substantial-albeit volatileportfolio and "other" net outflows. Net direct investment has tended to record large surpluses, though these have been on a declining path in recent years following the completion of major refining and chemicals projects. There was also a notable shift in the nature of financial outflows Last year was not exceptional: in fact, the financial account recorded a smaller deficit than in 2014 (\$42 billion vs $57 billion). However, there was a notable change in the nature of the outflows. The main outflow was on the "other investment" channel, especially flows listed as "currency and deposits". These were worth $20.6 billion in 2015, a $12 billion increase on 2014. Conversely, trade credits outflows - that is credit extended by Saudi exporters-declined by $10.5 billion to $19.9 billion as the value of foreign trade contracted. Gaudi Arahia. Cinanrial Arrount The rest of the NFA drawdown is accounted for by net errors and omissions, which increased by just over $10 billion to $20 billion. This item has been larger in the past, but has trended down recently as reporting and surveillance have improved. The increase in private outflows does not appear to signal a loss of confidence Is the increase in "currency and deposits" outflows a cause for alarm? In absolute terms, the $21 billion outflow is not especially large, and as we have seen, its impact on the overall balance of payments was almost fully offset by the reduction in trade credit outflows. However, a pickup of private outflows could be worrisome if it were part of a more general deterioration in confidence. There are two other barometers to check here: first is the proportion of foreign exchange held in local bank accounts. This has not been a pressing issue since 2009 in the depths of the global financial crisis, when the proportion rose to 17 percent (but could be seen as part of a generalised flight to safety). In fact, the ratio touched a new low of 9.1 percent at the end of the third quarter last year, long after oil prices had started to decline. However, in the past two quarters the proportion of forex has started to rise again, reaching 11.3 percent at the end of March. The other sensitive indicator is the amount of forex being sold by local banks to customers in the Kingdom (excluding government, personal transfers and import financing). This saw a sharp surge in the second quarter of last year, when such sales rose by $23 billion to reach $64 billion. There was no obvious catalyst: oil prices began to fall in the middle of the previous year and in fact posted a mild recovery in the second quarter. However, it may be that local corporates began to hedge their currency positions more actively once pressure on the exchange rate began to emerge, as it did in the first quarter. Sales of forex to local customers continued at this level for the rest of the year, before easing slightly in the first quarter of 2016 . Neither of these indicators appears to support the notion that the outflows of "currency and deposits" represents capital "flight" that might be a precursor to a classic balance of payments crisis. The recent uptick in the forex ratio warrants continued monitoring, but at 11.3 percent the ratio is low by historical standards. Nor has there been any shift from time and savings deposits to demand deposits, which might also indicate some unease among firms and households (in fact, the fortunes of the stock market continue to have a much more pronounced impact on this ratio). The spike in forex sales was large, but is not unprecedented (there were similar surges in 2007-08). In fact the spike can be seen as reassuring if it does indeed reflect a more active management of exchange rate exposures by local corporates. Following the pronounced deterioration last year and most likely this year too, we think the balance of payments is set to improve in 2017-20, and in this section we explain why. The starting point is clearly oil prices, which we see improving as stocks are worked down thanks to a combination of recovering demand and softening output (see our Oil Market Chartbook, May 2016). This will underpin rising oil export earnings, which will also be supported by moderate gains in oil output and the impact of subsidy cuts on domestic oil consumption, which will free up more oil for export (we estimate that this additional oil will be worth some $70 billion over the next five years). Nonoil exports are a key feature of the Saudi government's "Vision 2030" not surprisingly given the government's strategic aim of reducing the country's dependence on oil. Nonoil exports have grown quickly in value terms in recent years, reaching over $58 billion in 2014-almost 100 percent higher than five years previously. Plastics and chemicals have been the main growth (and value added) items. The main market here is Asia, though the UAE is also an important source of demand for Saudi steel and-depending on prevailing export rules-cement. Petrochemicals exports are facing strategic challenges A good deal of investment (both foreign and domestic) has been channelled towards petrochemicals. The sector is blessed with cheap gas feedstock, though prices are now rising and the differential with US producers, which have benefitted from cheap shale gas and oil, has narrowed significantly. In addition, lower oil prices have squeezed revenues, since most petchem prices are linked to the price of oil. Government policy could also be a headwind for profitability given the likelihood of further rises in domestic energy and feedstock prices. Moreover, Middle East chemicals producers are generally less efficient in global terms (typical operational costs for a cracker tend to be 35-40 percent higher than in China and 5-10 percent higher than in the US). Taking a positive view, one might say that there is considerable scope to reduce costs to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Saudi producers have the ability to tap into the Chinese automotive sector, with all the potential that that brings. But they will need to up their game as China's own keenly competitive petchems sector is rapidly expanding. Religious tourism has considerable potential to boost the services account Religious tourism is well placed to In terms of nonoil services, religious tourism provides plenty of potential to enhance foreign earnings. This provided $10 billion of foreign earnings in 2013 , but has potential to grow given the ongoing investment in hospitality, retail and transport infrastructure in the Mecca, Medina and Jeddah region. Encouragingly, the average number of nights spent per tourist is climbing, while spending per tourist trip is also trending up, and hotels are reporting 80 - 90 percent capacity, even during the off season. The government has rightly focused on religious tourism in its Vision 2030 and we think it offers good potential as a means of augmenting nonoil earnings. Import spending is likely to adjust more rapidly this year... What about outflows on the current account? As noted above, import spending took time to adjust to the collapse of oil prices, and declined by just 2 percent last year. We expect a sharper correction this year given the government's focus on rationalising procurement and investment spending within the public sector. The private sector began to adjust in around the first quarter of last year and is likely to continue to compress its spending for this year at least. The trend should begin to reverse in 2017 once the government relaxes its fiscal stance somewhat and we anticipate import spending growth averaging some 4.5 percent in the 201720 period. Workers' remittances outflows are set to decline this year before staging a mild recovery in 2018-20 in line with the recovery in government spending. The main invisible outflow on the current account is outward remittances. These are difficult to forecast, but tend to follow government spending with something of a lag (thus if the government raises spending significantly in year one, transfers outflows tend to increase in year two). This would appear to be the trend this year with personal transfers down 9 percent in the first quarter, year on year. Thus one might expect declines in remittances outflows this year and next, before a mild recovery in 2018-20. ...but the current account is still set to record a large deficit this year Given these trends-a marked deterioration in the visible trade balance allied to a less pronounced improvement in the invisibles balance-the current account deficit is set to widen quite sharply this year, reaching almost $75 billion, or 12 percent of GDP, the biggest such deficit since 1993. From next year on, the situation should improve, with a recovering trade surplus outstripping a widening invisibles deficit, so that by 2019 the current account should return to surplus, with an expected surplus of about 4.5 percent of GDP by end-2020. Direct investment inflows should broaden and deepen The financial account is more difficult to predict, given both a lack of historical data, the volatility of flows, and uncertainties regarding the pace of economic reform in the Kingdom. As noted above, direct investment inflows have dwindled in recent years as petrochemicals investors have tended to focus on Louisiana rather than Saudi Arabia. This is a structural shift that seems unlikely to reverse in the near- to medium-term, but we do anticipate a broadening of potential inward investment as the government moves to open up sectors such as health, education, transport and municipal services (among others) to foreign investment as part of its National Transformation agenda. Clearly, smooth progress in the liberalisation agenda is not guaranteed, and regional political discord could still be off-putting to many potential foreign investors, but inward direct investment should be pushing $15 billion by 2020. As the domestic economy improves and more reforms are enacted, so opportunities for domestic investors should multiply, helping to keep annual direct outflows at below $5 billion annually. Portfolio inflows have considerable potential, especially if the Tadawul is included in the MSCI EM Portfolio investment has traditionally been a heavy outflow, with the domestic stock market largely closed off to foreigners and Saudis often keen to invest in more developed markets. However, this should change over the next five years as the Tadawul continues to lift restrictions in a bid to attract more foreign institutional investors. There have been some significant recent announcements on this front, such as the lifting of restrictions on short-selling, planned for next year. Of even greater potential is the Tadawul's likely inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Market index-a move that we expect in 2017. Inclusion in this index will mean an automatic allocation of assets by large fund managers, with additional flows attracted by the sheer size of the market and, hopefully, an improving corporate performance. By 2020 we think that such inflows could be worth more than $20 billion a year. As with FDI, we assume that more Saudi capital will be tempted to stay at home if the local stock market is enlivened by increased foreign inflows. We therefore think that net portfolio flows should move from a moderate negative to a substantial positive in the years ahead. It is important to note that we have not included any sale of Saudi Aramco in our forecasts, owing to uncertainties about the company's valuation and the size and location of the offering. Clearly, this provides considerable upside risk to the portfolio inflows outlook-and indeed the entire balance of payments. The substantial deficit on the financial account is set to ease substantially over the next five years. An important inflow will be portfolio investment, which is set to accelerate as the Tadawul is further liberalised and the TASI is included in the MSCI EM. Direct investment inflows should Private outflows should diminish as domestic opportunities improve also pickup in line with the government's privatisation Flows on the "other investment" column are likely to remain substantially programme and more general negative. SAMA data indicate that this includes debt flows, and our revised liberalisation policies. working assumption is that the government will take on a total of $55 billion in debt during 2016-18 (it has already secured $10 billion of this in a syndicated loan). We do not think that further sovereign debt inflows will be necessary beyond 2018 , though there may well be some corporate debt There will still be substantial issuance. We noted in the first section the large outflows recorded as general we expect more Saudi for the reasons stated above, we do not think this amounts to meaningful capital to remain in the country "capital flight" and expect that the increase in these flows will be contained to as domestic investment 5 percent this year. Moreover, as the economic climate improves and worries opportunities improve. recede, so these outflows should soften. However, the impact on the financial account could be fully offset by an expansion of trade credits as trade recovers in the second part of the forecast period. Thus, on average, "other investment" flows will remain a substantial net negative at about $24 billion. The final channel on the balance of payments is net errors and omissions. By its nature this is tricky to forecast, but we have decided to include the government's fiscal financing activity in this column (excluding the sovereign debt issuance). Technically, the non-trade outflows stemming from fiscal financing should be captured in private flows, but for simplicity's sake we have decided to project them in this channel. Fiscal financing flows will be heavy this year, with some $35 billion required to close the gap not covered by domestic or external debt issuance. There should be a marked improvement from next year onwards as oil prices recover and the fiscal deficit narrows, so that by 2019 these flows should have dwindled to nothing (in theory at least; in reality net errors and omissions will still occur). NFA expected to stabilise at 48 percent of GDP by 2020 and to begin rising in nominal terms Where does all this leave net foreign assets? The short answer is that they will continue to decline as a proportion of GDP before stabilising at some 48 percent in 2020. In nominal terms we expect further declines, but at a slowing pace. By 2020 we think that NFA will begin to increase again, reaching $435 billion that year. Though substantially diminished compared with 2015, NFA Overall, we think the outlook for would still be equivalent to a very healthy 31 months of imports in 2020. the balance of payments is positive. This year will be tough, It is also worth reiterating that this projection does not include any proceeds but the situation should improve from the possible sale of Saudi Aramco. Assuming that the company was substantially in the next few valued at $2 trillion, with 5 percent offered for sale, and half of the take up years, allowing NFA to stabilise coming from abroad (either through a dual listing or with foreign investors as a proportional of GDP and taking a stake in the local offering) then this would raise some $50 billion in even pick up in nominal terms foreign exchange. In this event, NFA would be worth some 53 percent of GDP by 2020. in 2020 , compared with 42 percent under our existing forecast. Balance of payments position should become a net positive assuming oil prices pick up and the liberalisation programme proceeds In summary, the balance of payments will shift over time from quite a pronounced headwind to a mild tailwind, so that by 2020 NFA are being accumulated once more. There are a lot of variables at play, not least oil prices, which will remain the main influence on the current account. The current account would adjust more quickly were the exchange rate to be liberalised given that import demand would almost certainly be dampened. However, the peg plays a key role as a nominal anchor for the economy and will be an important consideration for potential foreign investors, who will become the main influence on the financial account as the government steps up efforts to liberalise the economy in the years ahead. As such, we think the peg will remain intact, and we therefore expect that the Saudi riyal will strengthen against other main currencies such as the euro and the yen in the next three years. This reflects monetary policy divergence between the US on the one hand (tightening) and the Eurozone and Japan on the other (easing). By 2018 we would expect to see the Eurozone and Japan begin to tighten, meaning that the USD (and SR) will begin to ease slightly against these currencies