Answer the following questions based on the article and explain your answer. Correlations among Stress, Physical Activity and Nutrition: School Employee Health Behavior

- Are the research problems, methods, and findings appropriate given the researchers' institutional affiliations, beliefs, values, or theoretical orientation?

- Do the researchers demonstrate any favorable or unfavorable bias in describing the subject of the study (e.g., the instructional method, program, curriculum, etc.) that was investigated?

- Is the literature review section of the report sufficiently comprehensive and does it include studies that you know to be relevant to the problem?

- Is each variable in this study clearly defined?

- Is the measure of each variable consistent with how the variable was defined?

- Are the research hypothesis, questions, or objectives explicitly stated, and, if so, are they clear?

- Do the researchers make a convincing case that a research hypothesis, question, or objective was important to study?

- Did the sampling procedures produce a sample that is representative of an identifiable population or that is generalizable to your local population?

- Did the researchers form subgroup to increase understanding of the phenomena being studied?

- Is each measure appropriate for the sample?

- Is each measure in this study sufficiently valid for its intended purpose?

- Is each measure in this study sufficiently reliable for its intended purpose?

- If any qualitative data were collected, were they analyzed in a manner that contributed to the soundness of the overall research design?

- Were the research procedures appropriate and clearly stated so that others could replicate them if they wished to do so?

- Were appropriate statistical techniques used, and were they used correctly?

- What is the practical significance of statistical results considered?

- Do the results of the data analysis support what the researchers conclude are the findings of the study?

- Did the researchers provide reasonable explanations of the findings?

- Did the researchers relate the findings to a particular theory or body of related research?

- Did the researchers identify sound implications for practice from their findings?

- Did the researchers suggest further research to build on their results or to answer questions that were raised by their findings?

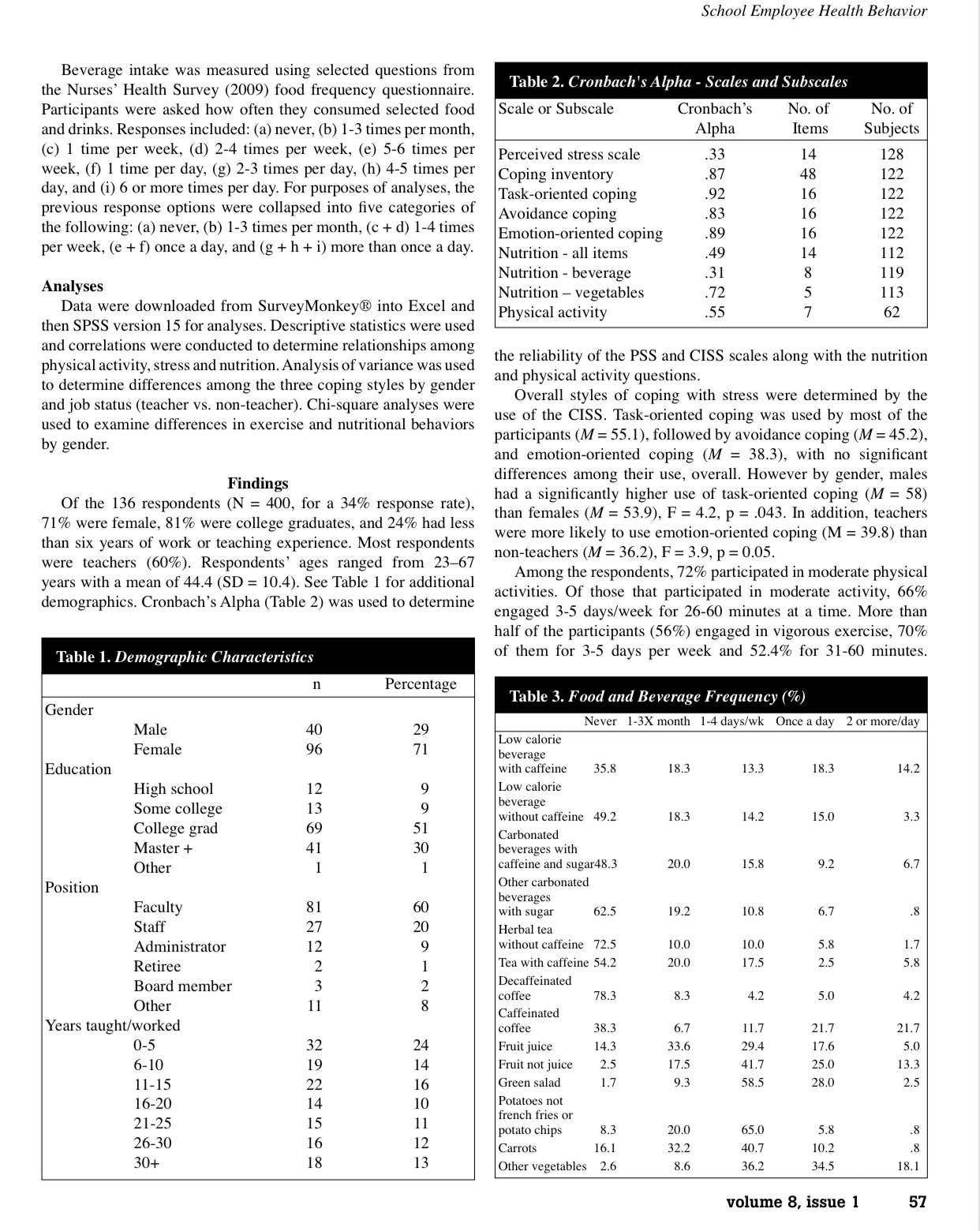

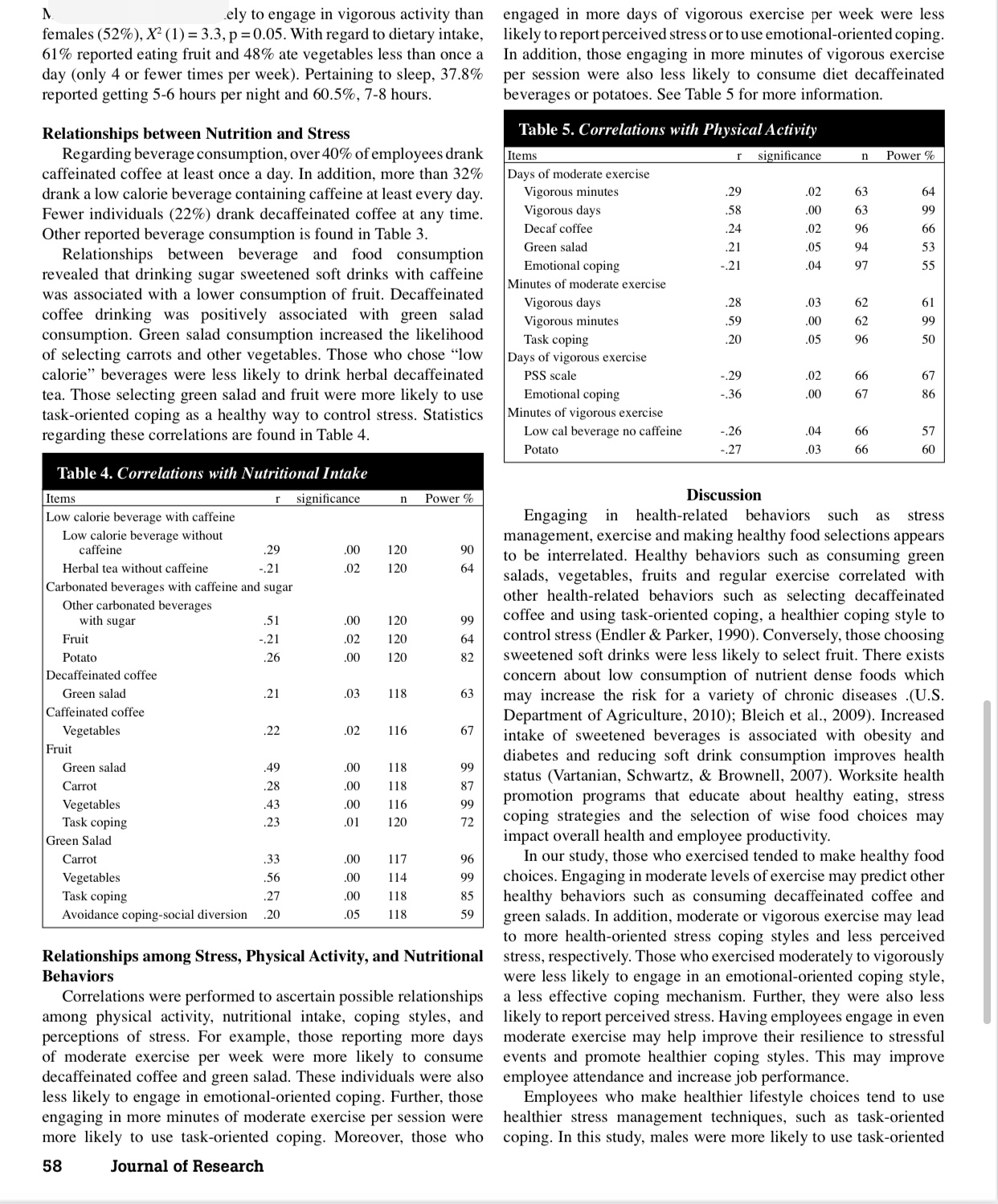

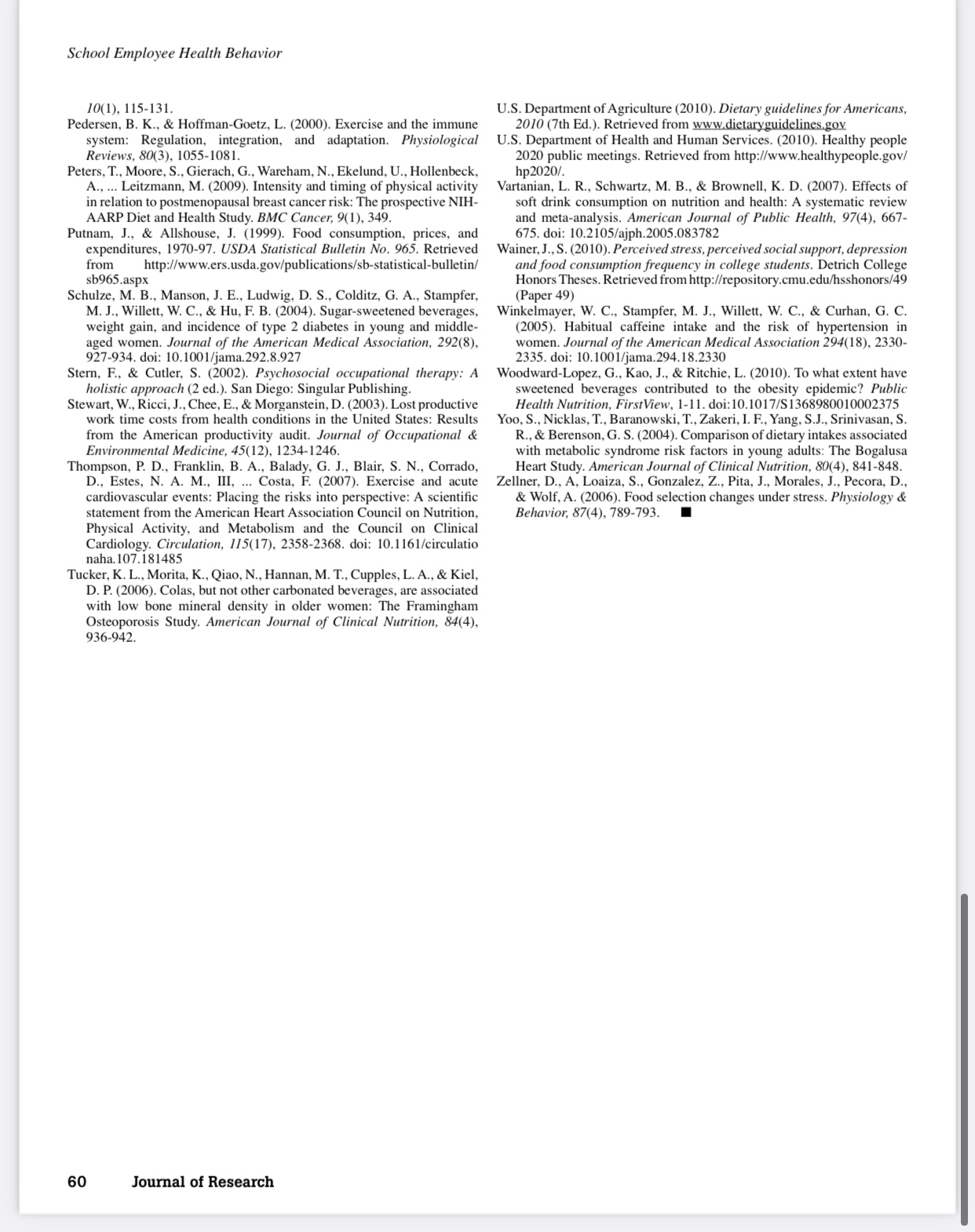

Beverage intake was measured using selected questions from the Nurses' Health Survey (2009) food frequency questionnaire. Participants were asked how often they consumed selected food and drinks. Responses included: (a) never, (b) 1-3 times per month, (c) 1 time per week, ((1) 2-4 times per week, (e) 5-6 times per week, (1') 1 time per day, (g) 2-3 times per day, (h) 4-5 times per day, and (i) 6 or more times per day. For purposes of analyses, the previous response options were collapsed into ve categories of the following: (a) never, (b) 1-3 times per month, (c + (1) 1-4 times per week, (e + f} once a day, and (g + h + i) more than once a day. Analyses Data were downloaded from SurveyMonkey into Excel and then SPSS version 15 for analyses. Descriptive statistics were used and correlations were conducted to determine relationships among physical activity, stress and nutrition. Analysis of variance was used to determine differences among the three coping styles by gender and job status (teacher vs. non-teacher). Chi-square analyses were used to examine differences in exercise and nutritional behaviors by gender. Findings Of the 136 respondents (N = 400, for a 34% response rate), 71% were female, 31% were college graduates, and 24% had less than six years of work or teaching experience. Most respondents were teachers (60%). Respondents' ages ranged from 2367 years with a mean of 44.4 (SD = 10.4). See Table 1 for additional demographics. Cronbach's Alpha (Table 2) was used to determine Table l. llt'magrtmht'c ( 'lmt'ttcltv't'slt'c's n Percentage Gender Male 40 29 Female 96 71 Education High school 12 9 Some college 13 9 College grad 69 51 Master + 41 Other 1 1 Position Faculty 81 60 Staff 27 20 Administrator 12 9 Retiree 2 1 Board member 3 2 Other 11 3 Years taughtlworked 0-5 32 24 6- 10 19 14 11-15 22 16 16-20 14 10 21-25 15 11 26-30 16 12 30+ 13 13 School Employee Health Behavior Table 2. ('mnbrit'lt '5: . llphrt - .'u't'alr's' mm" .Strl.1.'\\.'t't'tlc.~' Scale or Subscale Cronbach's No. of No. of Alpha Items Subjects Perceived stress scale .33 14 123 Coping inventory .37 43 122 Task-oriented coping .92 16 122 Avoidance coping .33 16 122 Emotion-oriented coping .39 16 122 Nutrition - all items .49 14 112 Nutrition - beverage .31 8 119 Nutrition vegetables .72 5 113 Physical activity .55 7 62 the reliability of the PSS and CISS scales along with the nutrition and physical activity questions. Overall styles of coping with stress were determined by the use of the C185. Task-oriented coping was used by most of the participants (M: 55.1), followed by avoidance coping (M = 45.2), and emotion-oriented coping (M = 33.3), with no signicant differences among their use, overall. However by gender, males had a signicantly higher use of task-oriented coping (M = 53) than females (M = 53.9), F = 4.2, p = .043. In addition, teachers were more likely to use emotion-oriented coping (M = 39.3) than non-teachers (M = 36.2), F = 3.9, p = 0.05. Among the respondents, 72% participated in moderate physical activities. Of those that participated in moderate activity, 66% engaged 3-5 dayslweek for 26-60 minutes at a time. More than half of the participants (56%) engaged in vigorous exercise, 70% of them for 3-5 days per week and 52.4% for 31-60 minutes. Table 3. Fund and lit-'l'cn'tg "runn-'ntji' Never l-3X month 1-4 dayslwk Once a day 2 or morelday Low calorie beverage with caffeine 35.3 18.3 13.3 13.3 14.2 Low calorie beverage without caffeine 49.2 18.3 14.2 15.0 3.3 Carbonated beverages with caffeine and sugar48.3 20.0 15.8 9.2 6.7 Other carbonated beverages with sugar 62.5 19.2 10.8 6.7 .8 Herbal tea without caffeine 72.5 10.0 10.0 5.8 1.7 Tea with caffeine 54.2 20.0 17.5 2.5 5.8 Decaffeinated coffee 78.3 8.3 4.2 5.0 4.2 Caffeinated coffee 38.3 6.7 11.7 21.7 21.7 Fmit juice 14.3 33.6 29.4 17.6 5.0 Fruit not juice 2.5 17.5 41.7 25.0 13.3 Green salad 1.7 9.3 53.5 23.0 2.5 Potatoes not french fries or potato chips 8.3 20.0 65.0 5.8 .8 Carrots 16.1 32.2 40.7 10.2 .8 Other vegetables 2.6 8.6 36.2 34.5 13.1 volume 8, issue 1 5? School Employee Health Behavior 2006), calcium excretion (Heaney & Rafferty, 2001). gout (Choi & Curhan, 2008; Winkelmayer, Stampfer, Willett, & Curhan, 2005), and pancreatic cancer (Larsson, Bergkvist, & Walk, 2006). High consumption of sugared beverages may also reduce intakes of more nutrient rich foods. adversely affecting health (Howard & Wylie-Rosett, 2002). Worksite stress may contribute to increased consumption of snack foods and sweets (Payne, Jones, & Harris, 2005). Consumption of sweet energy dense foods (high in rened sugar and fat) is associated with higher levels of perceived stress (Oliver. Wardle. 8r. Gibson, 2000). Further, individuals who are emotionally upset tend to choose more energy dense foods than those who are non- emotional eaters (Garg, Wansink, & Inman, 2007; Wainer, 2010; Zellner et al., 2006). One study found that teachers who exhibited high organizational climate scores (favorable relationship with co- workers and administrators) reported higher fruit and juice intake than did teachers with lower organizational climate (Cullen et al.. 1999). Another study examined job strain and its relationship to healthy eating and participation in exercise. Those who perceived higher job strain were more likely to eat energy dense foods, although there was no relationship between job strain and exercise behaviors (Payne et al.. 2005). Some studies have looked at the relationship between food consumption and stress. Fewer studies have examined the relationships among stress, physical activity and nutritional intake among school employees at the worksite. This study sought to determine associations among stress, physical activity, and specic food choices among employees in a southeastern Louisiana school district. Methods A convenience sample of employees who were eligible for participation in a rural southeastern Louisiana school board health promotion program (high school faculty and staff, employees of the school district and school board members) were sent an online questionnaire by email. Faculty and staff who did not respond after two or four weeks were sent a follow-up email with a survey link. Incentives were offered to faculty and staff members during all three waves of emails. After a random drawing, incentives of four $25.00 gift certicates to ofce supply stores were presented to participants. Questions consisted of demographic information, stress, physical activity and nutrition items. We used two instruments to measure perceived stress, the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) (Endler & Parker, 1990) and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1933). Individuals were also asked certain items regarding physical activity from the NHANES (2007-2008) survey (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2000) and selected beverage and dietary questions from the Nurses' Health Study (2009). All items related to demographics. stress, physical activity, and nutrition were added into an electronic survey via SurveyMonkey. A team of experts in worksite health (academicians, practitioners, and content specialists) ensured content and face validity by completing the online survey and making suggestions to clarify content, except for questions from a standardized instrument. In turn. six teachers not participating in the study took the survey 56 Journal of Research and provided an estimated completion time of 15 minutes with additional suggestions for rewording of items. Estimated completion time was provided to survey participants. Instruments and Survey Items The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), developed by Cohen, et al. (1983), measures perception of stress, specically the degree to which individuals appraise situations in life as being stressful by being unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloaded. This 14-item scale asks about feelings and thoughts during the past month. Participants were asked how often they had felt a certain way. A sample item was, \"In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened to you unexpectedly?" Likert-type scale responses included the following: never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often and very often. The level of readability for the P85 is that of a junior high school reading level. To calculate a total level of perceived stress, seven items are reverse scored and then all are summed. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress. Previously determined alpha coefcients of reliability for this instrument were .84, .35, and .86 (Cohen et al., 1983). The second stress instrument used in this study was the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (ClSS) (Endler & Parker, 1990) which has 43 items. The three main subscales of the C188 include task-oriented, emotion-oriented and avoidance coping with each having 16 items and a possible range of scores from 16-80. Task- oriented coping is directed toward problem solving which includes cognitive restructuring and actions to change a situation. Emotion- oriented coping involves emotional reactions that are self-oriented such as self-blame, anger and becoming tense. Avoidance coping consists of activities or thoughts aimed at curtailing a stressful situation by escaping a situation such as engaging in social activities or performing non-problem related tasks. Avoidance coping is divided into two additional scales: distraction and social diversion. The distraction subscale contains eight items with a score range of 8-40; the social diversion subscale has ve items with a range of 5-25. For each item on the C188, participants were asked to indicate how much they engaged in this activity when they encountered or experienced a difcult, stressful or upsetting situation. Sample items included: \"Feel anxious about not being able to cope"; \"Focus on the problem and see how I can solve it": and \"See a movie." Likert scale responses ranged from 1-5 with l=not at all to 5=very much. Physical activity questions were adapted from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) instrument ((CDC) 8:. (NCHS), 2000). Participants were provided examples of moderate activities such as brisk walking, vacuuming, or anything causing an increase in breathing or heart rate. They were then asked how many days they engaged in those activities for at least 10 minutes at a time. In addition to the number of days, participants were asked how much time (in minutes) they spent engaging in those activities. Similar questions were posed regarding vigorous exercise. Examples of vigorous exercise included running, aerobics, or anything that caused large increases in breathing or heart rate. Participants selected how many days they engaged in vigorous activities and the duration of those activities. School Employee Health Behavior coping than females. This may imply that the specific selection Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2000). National Health and of stress management techniques would be important in helping Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. female teachers and employees deal with perceived stress and Department of Health and Human Services. environmental demands. However workplace strategies should be Chapman, L. (2005). Healthier, happier, and more productive employees Retrieved August 14, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/ in place to help employees manage stress regardless of gender. docs/presentation_508.pdf Of course, self selection bias may have influenced these Choi, H. K., & Curhan, G. (2008). Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and results since those interested in health may also be more likely to the risk of gout in men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ, 336(7639), participate in this study. These individuals may be more likely to 309-312. doi: 10. 1136/bmj.39449.819271.BE participate and engage in a worksite health program and engage in Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 386-396. health enhancing behaviors. It would be beneficial to confirm these Cullen, K. W., Baranowski, T., Baranowski, J., Hebert, D., deMoor, C., results with a larger or more demographically varied sample. Hearn, M. D., & Resnicow, K. (1999). Influence of school organizational characteristics on the outcomes of a school health promotion program. Conclusion Journal of School Health, 69(9), 376-380. Since health-related behaviors appear to be linked in our study, Dhingra, R., Sullivan, L., Jacques, P. F., Wang, T. J., Fox, C. S., Meigs, J. B., ... Vasan, R. S. (2007). Soft drink consumption and risk of it may be helpful for those conducting school health promotion developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome programs to consider a multi-dimensioned approach in educational in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation, 116(5), 480-488. programming endeavors. Selecting strategies that address stress doi: 10.1161/circulationaha. 107.689935 management, nutritional intake and physical activity may impact Eaton, D. K., Marx, E., & Bowie, S. E. (2007). Faculty and staff health the health of school employees by reducing absenteeism and promotion: Results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. Journal of School Health, 77, 557-566. health care costs while improving staff productivity. Employees Endler, N., & Parker, J. (1990). Multidimentical assessment of coping: may benefit from having healthier food choices at the worksite A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, as they may be more likely to choose available healthier options. 58(5), 844-854. Providing more time for meals or other stress reducing strategies Garg, N., Wansink, B., & Inman, J., J. (2007). The influence of incidental affect on consumers' food intake. Journal of Marketing, 71, 194-206. may promote more healthful behaviors. In addition, having onsite Gold, Y. (1987). Stress reduction programs to prevent teacher burnout. facilities and programs may increase the likelihood of employees Education, 107(3), 338-341. participating in physical activity and stress management sessions Hammond, O. W., & Onikama, D. L. (1997). At risk teachers. Retrieved while promoting their well-being. Finally, providing stress breaks from http://www.prel.org/products/Products/AtRisk-teacher.pdf and promoting skills to reduce perceived stress could result in Heaney, R. P., & Rafferty, K. (2001). Carbonated beverages and urinary happier, healthier employees and reduce health care costs for calcium excretion. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(3), 343- 347. school systems. Howard, B. V., & Wylie-Rosett, J. (2002). Sugar and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the committee References on nutrition of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Allensworth, D., & Kolbe, L. (1987). The comprehensive school health Metabolism of the American Heart Association. Circulation, 106, 523- program: Exploring an expanded concept. Journal of School Health, 527 57(10), 409-412. Kaewthummanukul, T., & Brown, K. C. (2006). Determinants of employee Anderson, L.M., Quinn, T.A., Glanz, K., Ramirez, G., Kahwati, L.C., participation in physical activity: Critical review of the literature. Johnson, D.B., ... Katz, D.L. (2009). The effectiveness of worksite American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal, 54(6), nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee 249-261. overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Kant, A. K., & Graubard, B. I. (2006). Secular trends in patterns of self- Preventive Medicine, 37(4), 340-357. reported food consumption of adult Americans: NHANES 1971-1975 Anderson, V., Levinson, E., Barker, W., & Kiewra, K. (1999). The effects to NHANES 1999-2002. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, of meditation on teacher perceived occupational stress, state and trait 84(5), 1215-1223. anxiety, and burnout. School Psychology Quarterly, 14(1), 3-25 Larsson, S. C., Bergkvist, L., & Wolk, A. (2006). Consumption of sugar Austin, V., Shah, S., & Muncher, S. (2005). Teacher stress and coping and sugar-sweetened foods and the risk of pancreatic cancer in a strategies used to reduce stress. Occupational Therapy International, prospective study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 84(5), 2(2), 63-80. 1171-1176. Bernstein, L., Henderson, B., Hanisch, R., Sullivan-Halley, J., & Ross, R. Louis, Y., Schultz, A. B., Mcdonald, T., Champagne, L., & Edington, D. (1994). Physical exercise and reduced risk of breast cancer in young W. (2006). Participation in employer-sponsored wellness programs women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 86, 1403 -1408. before and after retirement. American Journal of Health Behavior, 30, Bleich, S. N., Wang, Y. C., Wang, Y., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2009). 27-38. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US Mather, A. S., Rodriguez, C., Guthrie, M. F., McHarg, A. M., Reid, I. adults: 1988-1994 to 1999-2004. The American Journal of Clinical C., & McMurdo, M. E. T. (2002). Effects of exercise on depressive Nutrition, 89(1), 372-381. symptoms in older adults with poorly responsive depressive disorder: Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Moore, K. A., Craighead, W. E., Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), Herman, S., Khatri, P., ... Krishnan, K. R. (1999). Effects of exercise 411-415. doi: 10.1192/bjp. 180.5.411 training on older patients with major depression. Archives of Internal Nagel, L., & Brown, S. (2003). The ABCs of managing teacher stress. Medicine, 159(19), 2349-2356. doi: 10.1001/archinte. 159.19.2349 Clearing House, 76(5), 255-258. Carnethon, M., Whitsel, L. P., Franklin, B. A., Kris-Etherton, P., Milani, Oliver, G., Wardle, J., & Gibson, E. L. (2000). Stress and food choice: A R., Pratt, C. A., & Wagner, G. R. (2009). Worksite wellness programs laboratory study. Psychosomtic Medicine, 62(6), 853-865. for cardiovascular disease prevention: A policy statement from the Payne, N., Jones, F., & Harris, P. (2005). The impact of job strain on the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120(17), 1725-1741. doi: predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour: An investigation 10.1161/circulationaha. 109. 192653 of exercise and healthy eating. British Journal of Health Psychology, volume 8, issue 1 59h. .ely to engage in vigorous activity than females (52%), X~' (I) = 3.3, p = 0.05. With regard to dietary intake, 61% reported eating fruit and 48% ate vegetables less than once a day (only 4 or fewer times per week). Pertaining to sleep, 37.8% reported getting 5-6 hours per night and 60.5%, 7-8 hours. Relationships between Nutrition and Stress Regarding beverage consumption, over 40% of employees drank caffeinated coffee at least once a day. In addition, more than 32% drank a low calorie beverage containing caffeine at least every day. Fewer individuals (22%) drank decaffeinated coffee at any time. Other reported beverage consumption is found in Table 3. Relationships between beverage and food consumption revealed that drinking sugar sweetened soft drinks with caffeine was associated with a lower consumption of fruit. Decaffeinated coffee drinking was positively associated with green salad consumption. Green salad consumption increased the likelihood of selecting carrots and other vegetables. Those who chose \"low calorie\" beverages were less likely to drink herbal decaffeinated tea. Those selecting green salad and fruit were more likely to use task-oriented coping as a healthy way to control stress. Statistics regarding these correlations are found in Table 4. Table 4. t 'I'u'n'lrrtinm' uv'tlr .\\"m'ritirumi Intake Items r signicance [1 Power \"K; Low calorie beverage with caffeine Low calorie beverage without caffeine .29 .00 I20 90 Herbal tea without caffeine -.21 .02 I20 64 Carbonated beverages with caffeine and sugar Other carbonated beverages with sugar .51 .00 I20 99 Fnlit -.21 .02 120 64 Potato .26 .00 120 82 Decaffeinated coffee Green salad .21 .03 118 63 Caffeinated coffee Vegetables .22 .02 116 67 Fruit Green salad .49 .00 118 99 Carrot .28 .00 1 18 87 Vegetables .43 .00 116 99 Task coping .23 .01 120 72 Green Salad Carrot .33 .00 1 17' 96 Vegetables .56 .00 114 99 Task coping .27 .00 118 85 Avoidance coping-social diversion .20 .05 118 59 Relationships among Stress, Physical Activity, and Nutritional Behaviors Correlations were performed to ascertain possible relationships among physical activity, nutritional intake, coping styles, and perceptions of stress. For example, those reporting more days of moderate exercise per week were more likely to consume decaffeinated coffee and green salad. These individuals were also less likely to engage in emotional-oriented coping. Further, those engaging in more minutes of moderate exercise per session were more likely to use task-oriented coping. Moreover, those who 58 Journal of Research engaged in more days of vigorous exercise per week were less likely to report perceived stress orto use emotional-oriented coping. In addition, those engaging in more minutes of vigorous exercise per session were also less likely to consume diet decaffeinated beverages or potatoes. See Table 5 for more information. Talllll' 5. ('nn'er'trtinm with I'h_1'\\it'uf.lz'tfl'r'ty' Items r signicance Days of moderate exercise Vigorous minutes .29 .02 63 64 Vigorous days .58 .00 63 99 Decaf coffee .24 .02 96 66 Green salad .21 .05 94 53 Emotional coping -.21 .04 97 55 Minutes of moderate exercise Vigorous days .28 .03 62 61 Vigorous minutes .59 .00 62 99 Task coping .20 .05 96 50 Days of vigorous exercise PSS scale -.29 .02 66 67 Emotional coping -.36 .00 67 86 Minutes of vigorous exercise Low cal beverage no caffeine -.26 .04 66 57 Potato .27 .03 66 60 Discussion Engaging in health-related behaviors such as stress management, exercise and making healthy food selections appears to be interrelated. Healthy behaviors such as consuming green salads, vegetables, fruits and regular exercise correlated with other health-related behaviors such as selecting decaffeinated coffee and using task-oriented coping, a healthier coping style to control stress (Endler& Parker, 1990). Conversely, those choosing sweetened soft drinks were less likely to select fruit. There exists concern about low consumption of nutrient dense foods which may increase the risk for a variety of chronic diseases .(U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2010); Bleich et al., 2009). Increased intake of sweetened beverages is associated with obesity and diabetes and reducing soft drink consumption improves health status (Vartanian, Schwartz, & Brownell, 2007). Worksite health promotion programs that educate about healthy eating, stress coping strategies and the selection of wise food choices may impact overall health and employee productivity. In our study, those who exercised tended to make healthy food choices. Engaging in moderate levels of exercise may predict other healthy behaviors such as consuming decaffeinated coffee and green salads. In addition, moderate or vigorous exercise may lead to more health-oriented stress coping styles and less perceived stress, respectively. Those who exercised moderately to vigorously were less likely to engage in an emotionaloriented coping style, a less effective coping mechanism. Further, they were also less likely to report perceived stress. Having employees engage in even moderate exercise may help improve their resilience to stressful events and promote healthier coping styles. This may improve employee attendance and increase job performance. Employees who make healthier lifestyle choices tend to use healthier stress management techniques, such as task-oriented coping. In this study, males were more likely to use task-oriented Correlations among Stress, Physical Activity and Nutrition: School Employee Health Behavior by Wynn Gillan, Millie Naquin, Marie Zannis, Ashley Bowers, fitness activities. According to the School Health Policies and Julie Brewer & Sarah Russell, Southeastern Louisiana University, Programs Study 2006, about two-thirds of states provided support Hammond, LA to school districts for activities and services that promote healthy lifestyles in faculty and staff (Eaton, Marx, & Bowie, 2007). In Abstract addition, Healthy People 2020 maintains the need to provide Employee health promotion programs increase work productivity comprehensive health promotion programs at the worksite (U.S. and effectively reduce employer costs related to health care and Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010). As absenteeism, and enhance worker productivity. Components of noted in Healthy People 2020 several components of an effective an effective worksite health program include stress management, worksite health program include stress management, employer- exercise and nutrition and/or weight management classes or based exercise facilities, and nutrition/weight management classes counseling. Few studies have documented correlates of health or counseling. behaviors in school-based employees. A multi-component survey Many school-based worksite programs include stress was used to examine relationships among stress, physical activity management strategies for staff. Stress is an inevitable part and specific food choices among employees in a southeastern of a school employee's life (Stern & Cutler, 2002) and the Louisiana school district. Significant differences were found physiological response may lead to teacher attrition, absenteeism in coping styles by gender and employee status. Findings also and other disorders such as anxiety and depression (Austin, Shah, indicated that employees who selected healthful foods were more & Muncher, 2005; Hammond & Onikama, 1997). As such, its likely to use task-oriented coping, considered an effective coping effects can be costly to the employer. Programs that help employees style. Further those employees who engaged in vigorous physical manage their stress have been shown to reduce anxiety, fatigue, activity on a regular basis reported less perceived stress as well as depression and teacher burnout (Anderson, Levinson, Barker, & more effective coping strategies. Since these behaviors appear to Kiewra, 1999). In a study of teachers, it was found that allowing be interrelated, those conducting health promotion programs may employees to identify their own levels of stress assisted them in consider a multi-dimensional approach when planning programs devising a personalized intervention program (Gold, 1987). for employees. Intervention studies in a school-based population Healthy People 2020 reports that physical activity is among are needed to examine specific effects of different coping styles the leading indicators for sound health (USDHHS, 2010). In and healthy behaviors on employee productivity. turn, physical activity builds resilience to stress and provides Keywords: coping, worksite health promotion long-term effects in preventing future stress episodes (Nagel & Brown, 2003). Teachers who engage in both competitive and Introduction noncompetitive forms of physical activity are found to have lower Given the current economic conditions, inclusion of health levels of stress than their higher-stressed counterparts (Austin et promotion programs is becoming a more important component of al., 2005). Furthermore, physical activity reduces the physical worksite health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicators of stress including inflammatory markers (Pedersen & report that employers, on average, spend $1,685 per employee Hoffman-Goetz, 2000). For instance, those who engage in physical per year for lost productivity costs related to health conditions activities often experience a reduction in their risk for high blood or $225.8 billion in the U.S. annually (Stewart, Ricci, Chee, pressure, high cholesterol (Thompson et al., 2007), diabetes, & Morganstein, 2003). Research further indicates that health cancer (Bernstein, Henderson, Hanisch, Sullivan-Halley, & Ross, promotion programs at worksites can result in a 25% reduction 1994; Peters et al., 2009), anxiety disorders (Mather et al., 2002), in costs associated with absenteeism, health care and disability and depression (Blumenthal et al., 1999). Also, it has been found workers' compensation (Carnethon et al., 2009; Chapman, 2005). that individuals with higher self-efficacy are more likely to engage Such programs are among the most useful non-medical strategies in physical activity (Kaewthummanukul & Brown, 2006). to improve and maintain the health of employees while controlling Worksite programs have also addressed the area of healthful health care costs (Louis, Schultz, Mcdonald, Champagne, & eating, particularly increasing nutrient dense foods and reducing Edington, 2006). Worksite health programs have also been found the intake of sugary ones. In the past two decades, sugared to improve dietary and physical activity behaviors (Anderson et beverage consumption has increased substantially (Bleich, Wang, al., 2009) both of which are imperative to employees' health. Wang, & Gortmaker, 2009; Kant & Graubard, 2006; Putnam & Worksite health promotion programs in school settings are Allshouse, 1999) and mirrors increased rates of many chronic among the eight interrelated components of the Coordinated conditions. Cohort studies have linked sweetened soft drinks with School Health Program, as recognized by the Centers for Disease obesity (Woodward-Lopez, Kao, & Ritchie, 2010), type 2 diabetes Control and Prevention (Allensworth & Kolbe, 1987). Under this (Schulze et al., 2004), and components of the metabolic syndrome component, teachers and non-teaching staff have the opportunity (Dhingra et al., 2007; Yoo et al., 2004). Certain types of sodas to participate in health assessments, education and health-related are associated with reduced bone mineral density (Tucker et al., volume 8, issue 1 55School Employee Health Behavior 10(1), 115-131. U.S. Department of Agriculture (2010). Dietary guidelines for Americans, Pedersen, B. K., & Hoffman-Goetz, L. (2000). Exercise and the immune 2010 (7th Ed.). Retrieved from www.dietaryguidelines.gov. system: Regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiological U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Healthy people Reviews, 80(3), 1055-1081. 2020 public meetings. Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/ Peters, T., Moore, S., Gierach, G., Wareham, N., Ekelund, U., Hollenbeck, hp2020/. A., ... Leitzmann, M. (2009). Intensity and timing of physical activity Vartanian, L. R., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (2007). Effects of in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer risk: The prospective NIH- soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: A systematic review AARP Diet and Health Study. BMC Cancer, 9(1), 349. and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 97(4), 667- Putnam, J., & Allshouse, J. (1999). Food consumption, prices, and 675. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2005.083782 expenditures, 1970-97. USDA Statistical Bulletin No. 965. Retrieved Wainer, J., S. (2010). Perceived stress, perceived social support, depression from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/sb-statistical-bulletin/ and food consumption frequency in college students. Detrich College sb965.aspx Honors Theses. Retrieved from http://repository.cmu.edu/hsshonors/49 Schulze, M. B., Manson, J. E., Ludwig, D. S., Colditz, G. A., Stampfer, (Paper 49) M. J., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2004). Sugar-sweetened beverages, Winkelmayer, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., & Curhan, G. C. weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle (2005). Habitual caffeine intake and the risk of hypertension in aged women. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(8), women. Journal of the American Medical Association 294(18), 2330- 927-934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927 2335. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.18.2330 Stern, F., & Cutler, S. (2002). Psychosocial occupational therapy: A Woodward-Lopez, G., Kao, J., & Ritchie, L. (2010). To what extent have holistic approach (2 ed.). San Diego: Singular Publishing. sweetened beverages contributed to the obesity epidemic? Public Stewart, W., Ricci, J., Chee, E., & Morganstein, D. (2003). Lost productive Health Nutrition, FirstView, 1-11. doi: 10.1017/$1368980010002375 work time costs from health conditions in the United States: Results Yoo, S., Nicklas, T., Baranowski, T., Zakeri, I. F., Yang, S.J., Srinivasan, S from the American productivity audit. Journal of Occupational & R., & Berenson, G. S. (2004). Comparison of dietary intakes associated Environmental Medicine, 45(12), 1234-1246. with metabolic syndrome risk factors in young adults: The Bogalusa Thompson, P. D., Franklin, B. A., Balady, G. J., Blair, S. N., Corrado, Heart Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 80(4), 841-848. D., Estes, N. A. M., III, ... Costa, F. (2007). Exercise and acute Zellner, D., A, Loaiza, S., Gonzalez, Z., Pita, J., Morales, J., Pecora, D., cardiovascular events: Placing the risks into perspective: A scientific & Wolf, A. (2006). Food selection changes under stress. Physiology & statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Behavior, 87(4), 789-793. Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation, 115(17), 2358-2368. doi: 10.1161/circulatio naha. 107.181485 Tucker, K. L., Morita, K., Qiao, N., Hannan, M. T., Cupples, L. A., & Kiel, D. P. (2006). Colas, but not other carbonated beverages, are associated with low bone mineral density in older women: The Framingham Osteoporosis Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 84(4), 936-942. 60 Journal of Research