Question: Assignment Question 1. Introduce the antagonist early in your answer . Always establish the problem before revealing your solution. You can do so by painting

Assignment Question

1. Introduce the antagonist early in your answer . Always establish the problem before revealing your solution. You can do so by painting a vivid picture of your customers pain points. Set up the problem by asking, Why do we need this?

2. Describe the problem in detail. Make it tangible. Build the pain.

3. Create an elevator pitch for your product using the four-step method described in this chapter. Pay particular attention to question number 2, What problem do you solve? Remember, nobody cares about your product. People care about solving their problems.

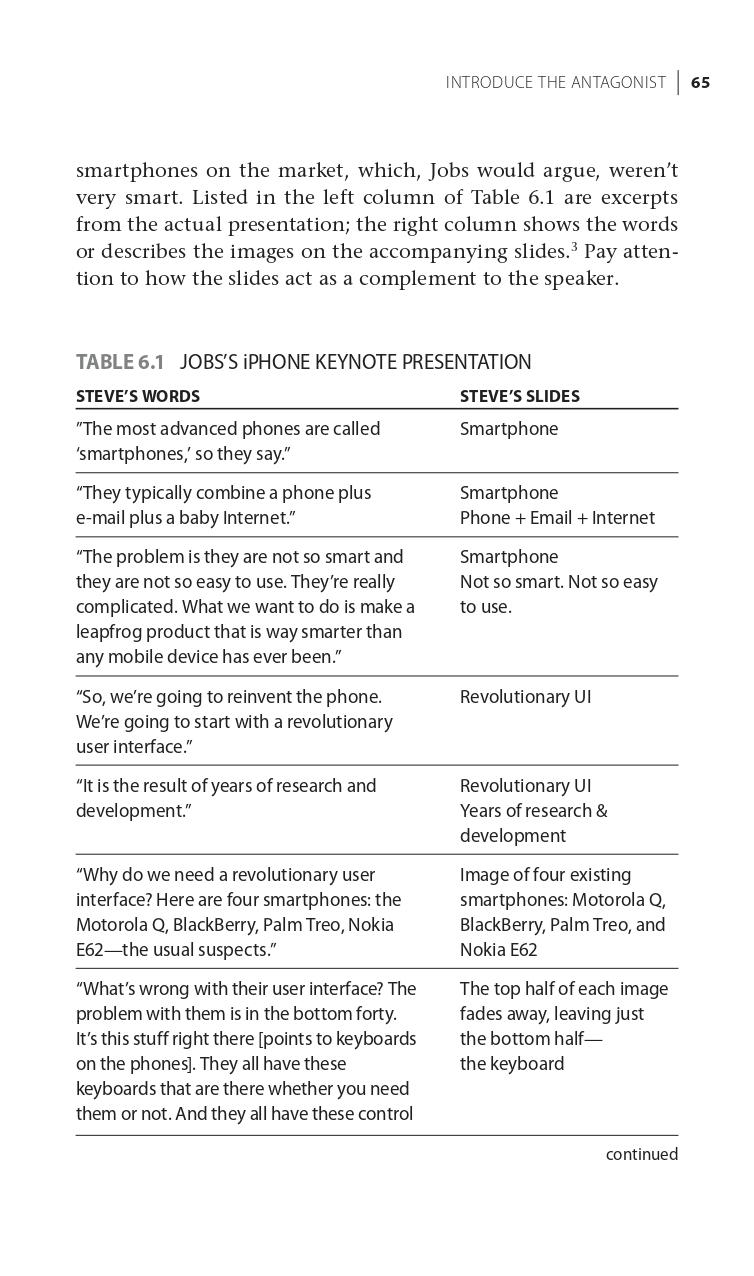

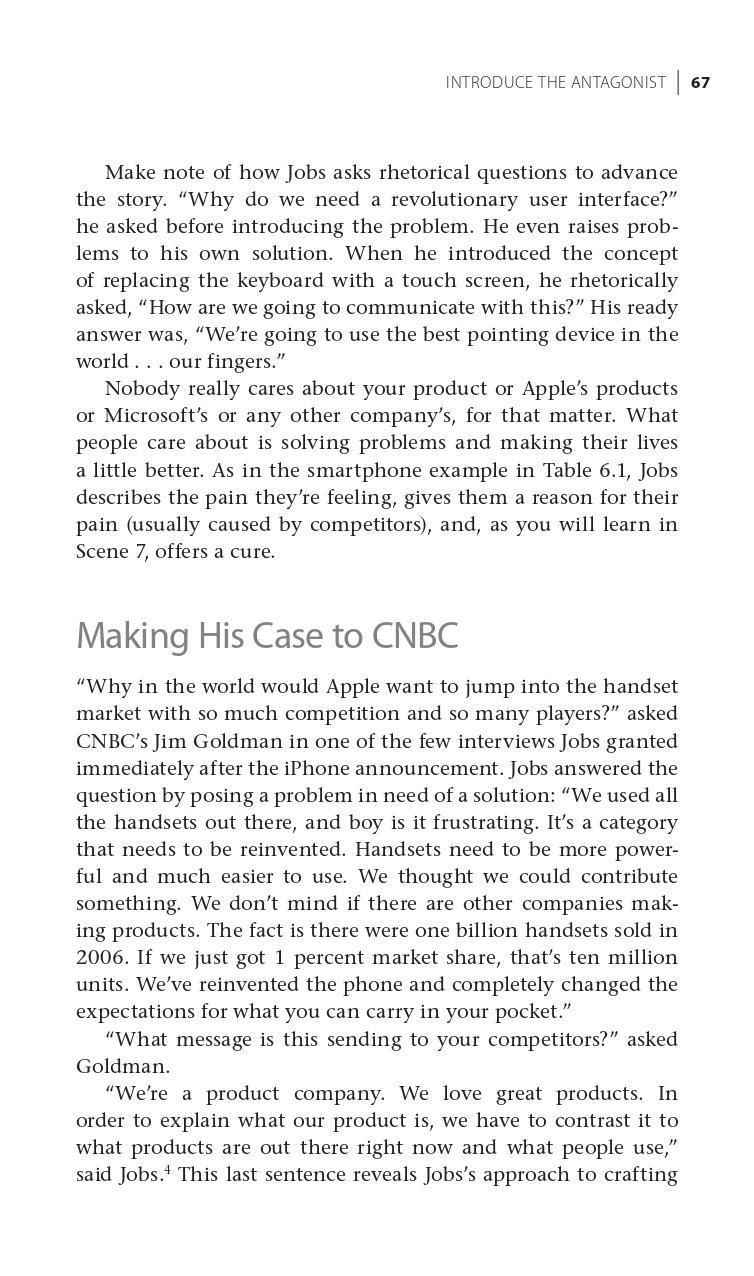

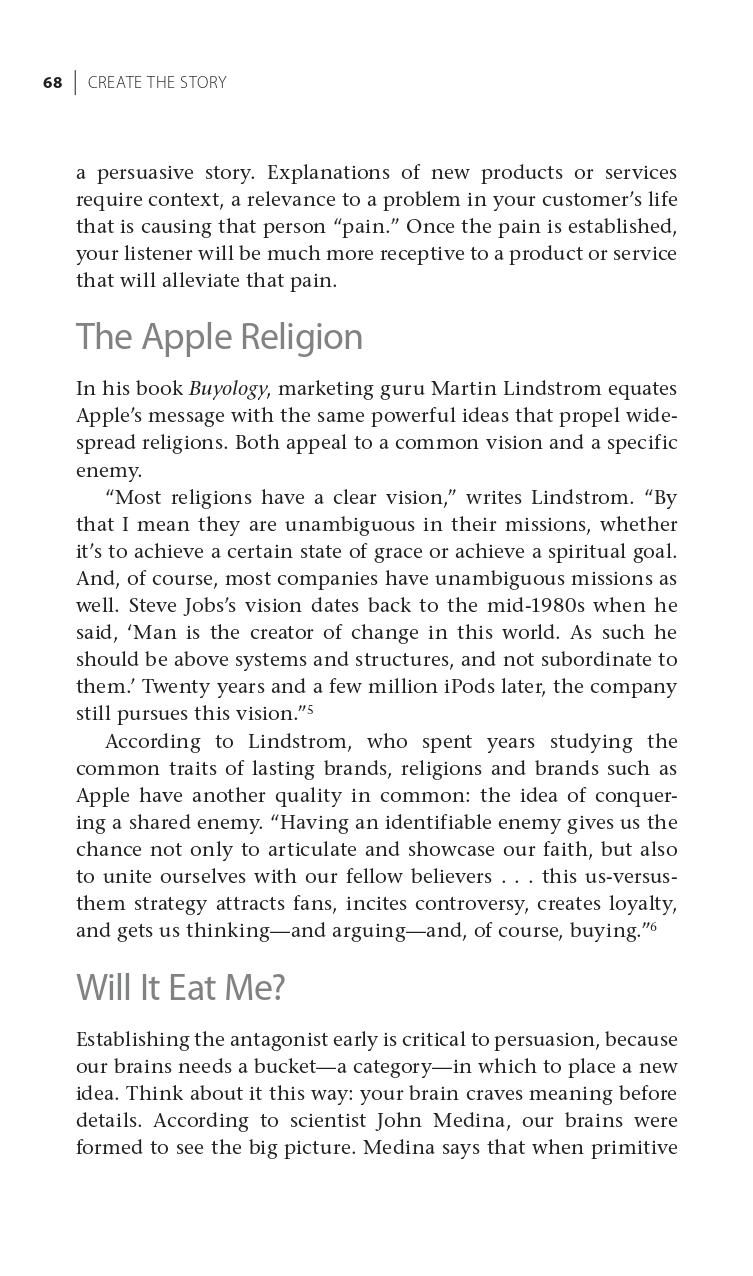

SCENE 6 STEMME Introduce the Antagonist Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? Was George Orwell right? -STEVE JOBS n every classic story, the hero fights the villain. The same storytelling outline applies to world-class presentations. Steve Jobs establishes the foundation of a persuasive story by introducing his audience to an antagonist, an enemy, a problem in need of a solution. In 1984, the enemy was "Big Blue." Apple is behind one of the most influential television ads in history and one in which we begin to see the hero-villain scenario playing out in Jobs's approach to messaging. The tele- vision ad, 1984, introduced Macintosh to the world. It ran only once, during the January 22 Super Bowl that same year. The Los Angeles Raiders were crushing the Washington Redskins, but more people remember the spot than the score. Ridley Scott, of Alien fame, directed the Apple ad, which begins with shaven-headed drones listening to their leader (Big Brother) on a giant screen. An athletic blonde, dressed in skimpy eighties-style workout clothes, is running with a sledgehammer. Chased by helmeted storm troopers, the girl throws the ham- mer into the screen, which explodes in a blinding light as the drones sit with their mouths wide open. The spot ends with | 63 64 | CREATE THE STORY a somber announcer saying, "On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh and you'll see why 1984 won't be like 1984."1 Apple's board members had unanimously disliked the com- mercial and were reluctant to run it. Jobs, of course, supported it, because he understood the emotional power behind the clas- sic story structure of the hero and villain. He realized every protagonist needs an enemy. In the case of the historic 1984 television ad, IBM represented the villain. IBM, a mainframe computer maker at the time, had made the decision to build a competitor to the world's first mass-market home computer, the Apple II. Jobs explained the ad in a 1983 keynote presentation to a select group of Apple salespeople who previewed the sixty- second television spot. "It is now 1984," said Jobs. "It appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money ... IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire com- puter industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right?"2 With that introduction, Jobs stepped aside as the assembled salespeople became the first public audience to see the commer- cial. The audience erupted into a thunderous cheer. For another sixty seconds, Steve remained onstage basking in the adulation, his smile a mile wide. His posture, body language, and facial expression said it allI nailed it! Problem + Solution = Classic Jobs Introducing the antagonist (the problem) rallies the audience around the hero (the solution). Jobs structures his most excit- ing presentations around this classic storytelling device. For example, thirty minutes into one of his most triumphant pre- sentations, the launch of the iPhone at Macworld 2007, he spent three minutes explaining why the iPhone is a product whose time has come. The villains in this case included all the current INTRODUCE THE ANTAGONIST | 65 smartphones on the market, which, Jobs would argue, weren't very smart. Listed in the left column of Table 6.1 are excerpts from the actual presentation; the right column shows the words or describes the images on the accompanying slides. Pay atten- tion to how the slides act as a complement to the speaker. TABLE 6.1 JOBS'S IPHONE KEYNOTE PRESENTATION STEVE'S WORDS STEVE'S SLIDES Smartphone Smartphone Phone + Email + Internet "The most advanced phones are called 'smartphones, so they say." "They typically combine a phone plus e-mail plus a baby Internet." "The problem is they are not so smart and they are not so easy to use. They're really complicated. What we want to do is make a leapfrog product that is way smarter than any mobile device has ever been." Smartphone Not so smart. Not so easy to use. Revolutionary UI "So, we're going to reinvent the phone. We're going to start with a revolutionary user interface." "It is the result of years of research and development." Revolutionary UI Years of research & development Image of four existing smartphones: Motorola Q, BlackBerry, Palm Treo, and Nokia E62 "Why do we need a revolutionary user interface? Here are four smartphones: the Motorola Q, BlackBerry, Palm Treo, Nokia E62the usual suspects." "What's wrong with their user interface? The problem with them is in the bottom forty. It's this stuff right there [points to keyboards on the phones). They all have these keyboards that are there whether you need them or not. And they all have these control The top half of each image fades away, leaving just the bottom half- the keyboard continued 66 | CREATE THE STORY TABLE 6.1 JOBS'S IPHONE KEYNOTE PRESENTATION (continued) STEVE'S WORDS STEVE'S SLIDES buttons that are fixed in plastic and are the same for every application. Well, every application wants a slightly different user interface, a slightly optimized set of buttons just for it. And what happens if you think of a great idea six months from now? You can't add a button to these things. They're already shipped. So, what do you do?" Image of iPhone "What we're going to do is get rid of all these buttons and just make a giant screen." Image of iPhone on its side; a stylus fades in "How are we going to communicate with this? We don't want to carry around a mouse. So, what are we going to do? A stylus, right? We're going to use a stylus." "No [laughs). Who wants a stylus? You have to get them out, put them awayyou lose them. Yuck. Nobody wants a stylus." Words appear next to image: Who wants a stylus? "So, let's not use a stylus. We're going to use the best pointing device in the world-a pointing device that we're all born with. We're born with ten of them. We'll use our fingers." Stylus fades out of frame as image of index finger appears next to iPhone "We have invented a new technology called 'multi-touch,' which is phenomenal." Finger fades out, and words appear: Multi-Touch "It works like magic. You don't need a stylus. It's far more accurate than any touch display that's ever been shipped. It ignores unintended touches. It's supersmart. You can do multi-finger gestures on it, and boy have we patented it!" [laughter] Words reveal upper right: Works like magic No stylus Far more accurate Ignores unintended touches Multi-finger gestures Patented INTRODUCE THE ANTAGONIST | 67 Make note of how Jobs asks rhetorical questions to advance the story. "Why do we need a revolutionary user interface?" he asked before introducing the problem. He even raises prob- lems to his own solution. When he introduced the concept of replacing the keyboard with a touch screen, he rhetorically asked, "How are we going to communicate with this?" His ready answer was, "We're going to use the best pointing device in the world ... our fingers." Nobody really cares about your product or Apple's products or Microsoft's or any other company's, for that matter. What people care about is solving problems and making their lives a little better. As in the smartphone example in Table 6.1, Jobs describes the pain they're feeling, gives them a reason for their pain (usually caused by competitors), and, as you will learn in Scene 7, offers a cure. Making His Case to CNBC "Why in the world would Apple want to jump into the handset market with so much competition and so many players?" asked CNBC's Jim Goldman in one of the few interviews Jobs granted immediately after the iPhone announcement. Jobs answered the question by posing a problem in need of a solution: "We used all the handsets out there, and boy is it frustrating. It's a category that needs to be reinvented. Handsets need to be more power- ful and much easier to use. We thought we could contribute something. We don't mind if there are other companies mak- ing products. The fact is there were one billion handsets sold in 2006. If we just got 1 percent market share, that's ten million units. We've reinvented the phone and completely changed the expectations for what you can carry in your pocket." "What message is this sending to your competitors?" asked Goldman. "We're a product company. We love great products. In order to explain what our product is, we have to contrast it to what products are out there right now and what people use," said Jobs. This last sentence reveals Jobs's approach to crafting 68 | CREATE THE STORY a persuasive story. Explanations of new products or services require context, a relevance to a problem in your customer's life that is causing that person "pain." Once the pain is established, your listener will be much more receptive to a product or service that will alleviate that pain. The Apple Religion In his book Buyology, marketing guru Martin Lindstrom equates Apple's message with the same powerful ideas that propel wide- spread religions. Both appeal to a common vision and a specific enemy. "Most religions have a clear vision," writes Lindstrom. "By that I mean they are unambiguous in their missions, whether it's to achieve a certain state of grace or achieve a spiritual goal. And, of course, most companies have unambiguous missions as well. Steve Jobs's vision dates back to the mid-1980s when he said, 'Man is the creator of change in this world. As such he should be above systems and structures, and not subordinate to them.' Twenty years and a few million iPods later, the company still pursues this vision."5 According to Lindstrom, who spent years studying the common traits of lasting brands, religions and brands such as Apple have another quality in common: the idea of conquer- ing a shared enemy. "Having an identifiable enemy gives us the chance not only to articulate and showcase our faith, but also to unite ourselves with our fellow believers ... this us-versus- them strategy attracts fans, incites controversy, creates loyalty, and gets us thinking-and arguing-and, of course, buying." Will It Eat Me? Establishing the antagonist early is critical to persuasion, because our brains needs a bucketa category-in which to place a new idea. Think about it this way: your brain craves meaning before details. According to scientist John Medina, our brains were formed to see the big picture. Medina says that when primitive INTRODUCE THE ANTAGONIST | 69 man saw a saber-toothed tiger, he asked himself, "Will it eat me?" and not "How many teeth does it have?" The antagonist gives your audience the big picture. Don't start with the details. Start with the key ideas and, in a hier- archical fashion, form the details around these larger notions," writes Medina in his book Brain Rules. In presentations, start with the big picturethe problem-before filling in the details (your solution). Apple unveiled the Safari Web browser during Macworld 2003, designating it the fastest browser on the Mac. Safari would join several other browsers vying for attention in the face of Microsoft's juggernaut-Internet Explorer. At his persuasive best, Jobs set up the problem-introducing the antagonist- simply by asking a rhetorical question: "Why do we need our own browser?"8 Before demonstrating the new featuresfilling in the details-he needed to establish a reason for the product's existence. Jobs told the audience that there were two areas in which competitors such as Internet Explorer, Netscape, and others fell short: speed and innovation. In terms of speed, Jobs said Safari would load pages three times faster than Internet Explorer on the Mac. In the area of innovation, Jobs discussed the limita- tions of current browsers, including the fact that Google search was not provided in the main toolbar and that organizing book- marks left a lot to be desired. "What we found in our research is that people don't use bookmarks. They don't use favorites very much because this stuff is complicated and nobody has figured out how to use it," Jobs said. Safari would fix the problems by incorporating Google search into the main toolbar and adding features that would allow users to more easily navigate back to previous sites or favorite Web pages. One simple sentence is all you need to introduce the antago- nist: "Why do you need this?" This one question allows Jobs to review the current state of the industry (whether it be brows- ers, operating systems, digital music, or any other facet) and to set the stage for the next step in his presentation, offering the solution. 70 | CREATE THE STORY The $3,000-a-Minute Pitch During one week in September, dozens of entrepreneurs pitch their start-ups to influential groups of media, experts, and investors at two separate venuesTechCrunch 50 in San Francisco and DEMO in San Diego. For start-up founders, these high-stakes presentations mean the difference between success and obsolescence. TechCrunch organizers believe that eight minutes is the ideal amount of time in which to communicate an idea. If you cannot express your idea in eight minutes, the thinking the goes, you need to refine your idea. DEMO gives its presenters even less timesix minutes. DEMO also charges an $18,500 fee to present, or $3,000 per minute. If you had to pay $3,000 a minute to pitch your idea, how would you approach it? The consensus among venture capitalists who attend the presentations is that most entrepreneurs fail to create an intriguing story line because they jump right into their product without explaining the problem. One investor told me, "You need to create a new space in my brain to hold the information you're about to deliver. It turns me off when entrepreneurs offer a solution without setting up the prob- lem. They have a pot of coffeetheir ideawithout a cup to pour it in." Your listeners' brains have only so much room to absorb new information. It's as if most presenters try to squeeze 2 MB of data into a pipe that carries 128 KB. It's simply too much. A company called TravelMuse had one of the most outstand- ing pitches in DEMO 2008. Founder Kevin Fleiss opened his pitch this way: "The largest and most mature online retail seg- ment is travel, totaling more than $90 billion in the United States alone [establishes category]. We all know how to book a trip online. But booking is the last 5 percent of the process [begins to introduce problem]. The 95 percent that comes before book- ing-deciding where to go, building a planis where all the heavy lifting happens. At TravelMuse we make planning easy by seamlessly integrating content with trip-planning tools to pro- vide a complete experience [offers solution]." By introducing INTRODUCE THE ANTAGONIST | 71 the category and the problem before introducing the solution, Fleiss created the cup to pour the coffee into. Investors are buying a stake in ideas. As such, they want to know what pervasive problem the company's product addresses. A solution in search of a problem carries far less appeal. Once the problem and solution are established, inves- tors feel comfortable moving on to questions regarding the size of the market, the competition, and the business model. The Ultimate Elevator Pitch The problem need not take long to establish. Jobs generally takes just a few minutes to introduce the antagonist. You can do so in as little as thirty seconds. Simply create a one-sentence answer for the following four questions: (1) What do you do? (2) What problem do you solve? (3) How are you different? (4) Why should I care? When I worked with executives at Language Line, in Monterey, California, we crafted an elevator pitch based on answers to the four questions. If we did our job successfully, the following pitch should tell you a lot about the company: "LanguageLine is the world's largest provider of phone interpretation services for com- panies who want to connect with their non-English-speaking customers [what it does]. Every twenty-three seconds, someone who doesn't speak English enters this country [the problem). When he or she calls a hospital, a bank, an insurance company, or 911, it's likely that a LanguageLine interpreter is on the other end [how it's different]. We help you talk to your customers, patients, or sales prospects in 150 languages [why you should care]." The Antagonist: A Convenient Storytelling Tool Steve Jobs and former U.S. vice president turned global warming expert Al Gore share three things in common: a commitment 72 CREATE THE STORY to the environment, a love for Apple (Al Gore sits on Apple's board), and an engaging presentation style. Al Gore's award-winning documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, is a presentation designed with Apple's storytelling devices in mind. Gore gives his audience a reason to listen by establishing a problem everyone can agree on (critics may differ on the solu- tion, but the problem is generally accepted). Gore begins his presentationhis storyby setting the stage for his argument. In a series of colorful images of Earth taken from various space missions, he not only gets audiences to appre- ciate the beauty of our planet but also introduces the problem. Gore opens with a famous photograph called "Earthrise," the first look at Earth from the moon's surface. Then Gore reveals a series of photographs in later years showing signs of global warming such as melting ice caps, receding shorelines, and hurricanes. "The ice has a story to tell us," he says. Gore then describes the villain in more explicit terms: the burning of fos- sil fuels such as coal, gas, and oil has dramatically increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the earth's atmosphere, causing global temperatures to rise. In one of the most memorable scenes of the documentary, Gore explains the problem by showing two colored lines (red and blue) representing levels of carbon dioxide and average tem- peratures going back six hundred thousand years. According to Gore, "When there is more carbon dioxide, the temperature gets warmer." He then reveals a slide that shows the graph climbing to the highest level of carbon dioxide in our planet's history- which represents where the level is today. "Now if you'll bear with me, I want to really emphasize this next point," Gore says as he climbs onto a mechanical lift. He presses a button, and the lift carries him what appears to be at least five feet. He is now parallel with the point on the graph representing current CO, emissions. This elicits a small laugh from his audience. It's funny but insightful at the same time. In less than fifty years," he goes on to say, "it's going to continue to go up. When some of these children who are here are my age, here's where it's going to be." At this point, Gore presses the button again, and the lift INTRODUCE THE ANTAGONIST | 73 carries him higher for about ten seconds. As he's tracking the graph upward, he turns to the audience and says, "You've heard of 'off the charts'? Well, here's where we're going to be in less than fifty years." 10 It's funny, memorable, and powerful at the same time. Gore takes facts, figures, and statistics and brings them to life. Gore uses many of the same presentation and rhetorical tech- niques that we see in a Steve Jobs presentation. Among them are the introduction of the enemy, or the antagonist. Both men introduce an antagonist early, rallying the audience around a common purpose. In a Jobs presentation, once the villain is clearly established, it's time to open the curtain to reveal the character who will save the day ... the conquering heroStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts