Question: Break-even points (pgs 220-221,232) Budget (pg 334) Differential Analysis: relevant costs & benefits (pgs. 508-512) The question was to answer or just give thoughts about

Break-even points (pgs 220-221,232)

Budget (pg 334)

Differential Analysis: relevant costs & benefits (pgs. 508-512)

The question was to answer or just give thoughts about the following pages. there's that required section

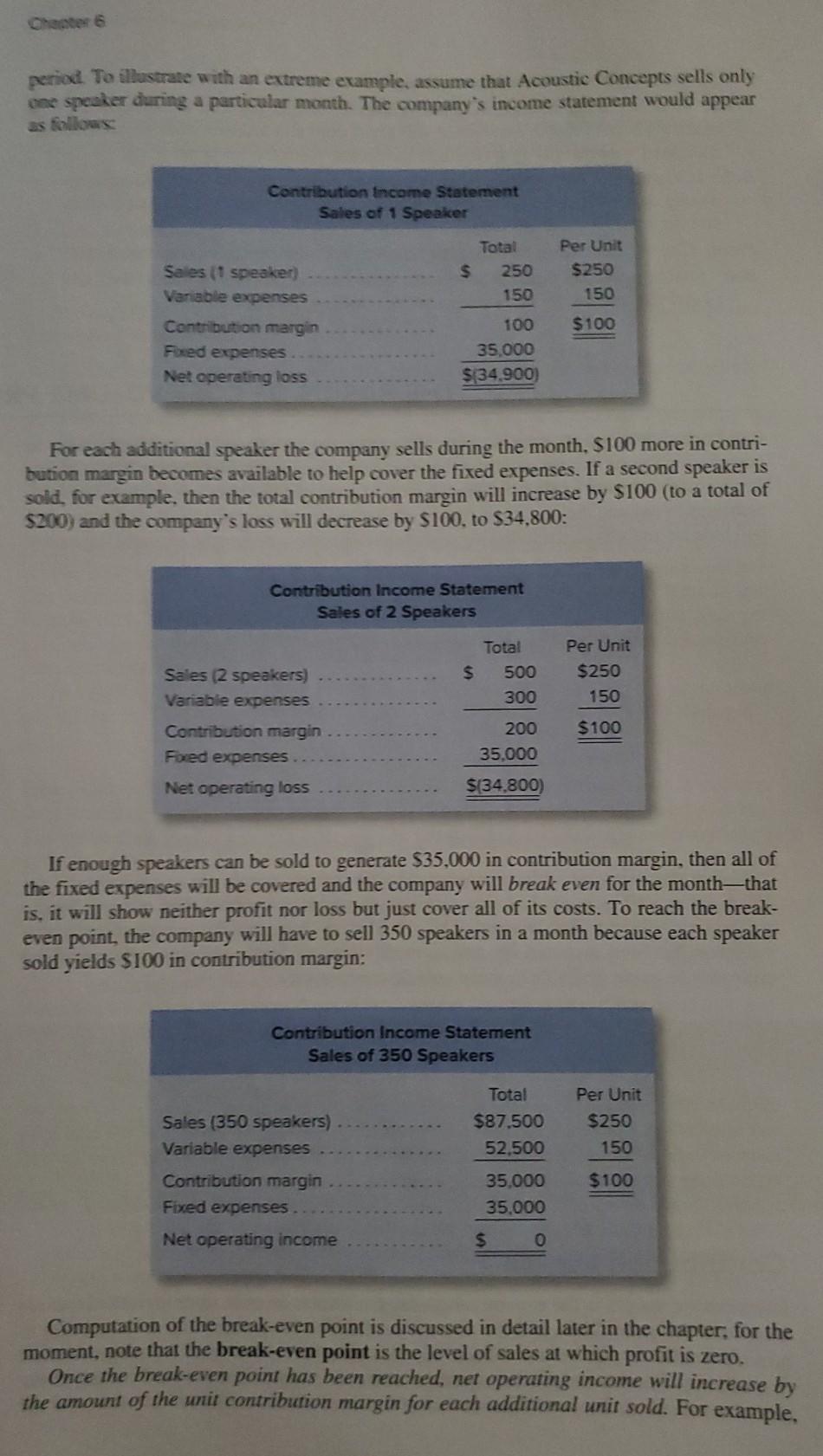

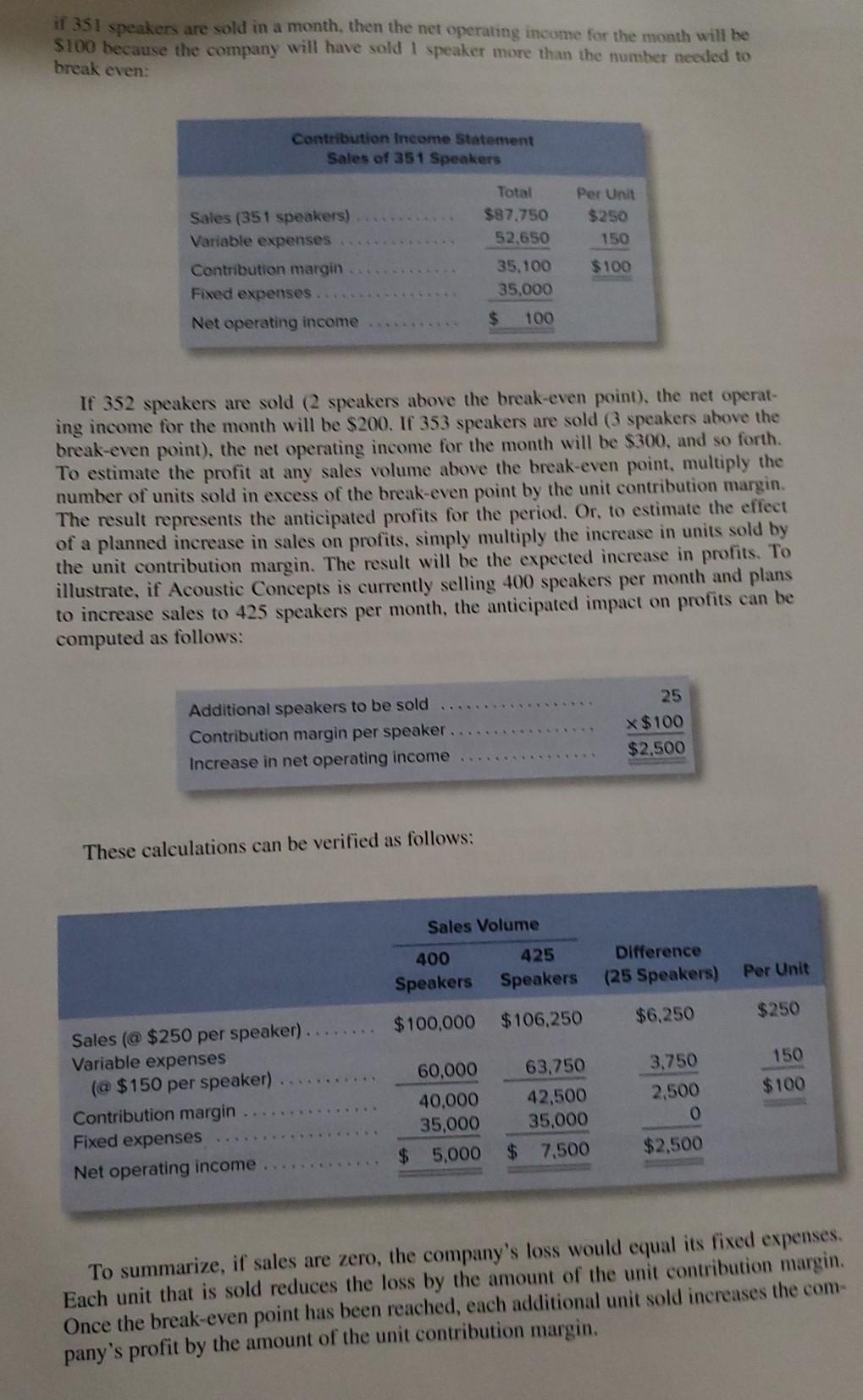

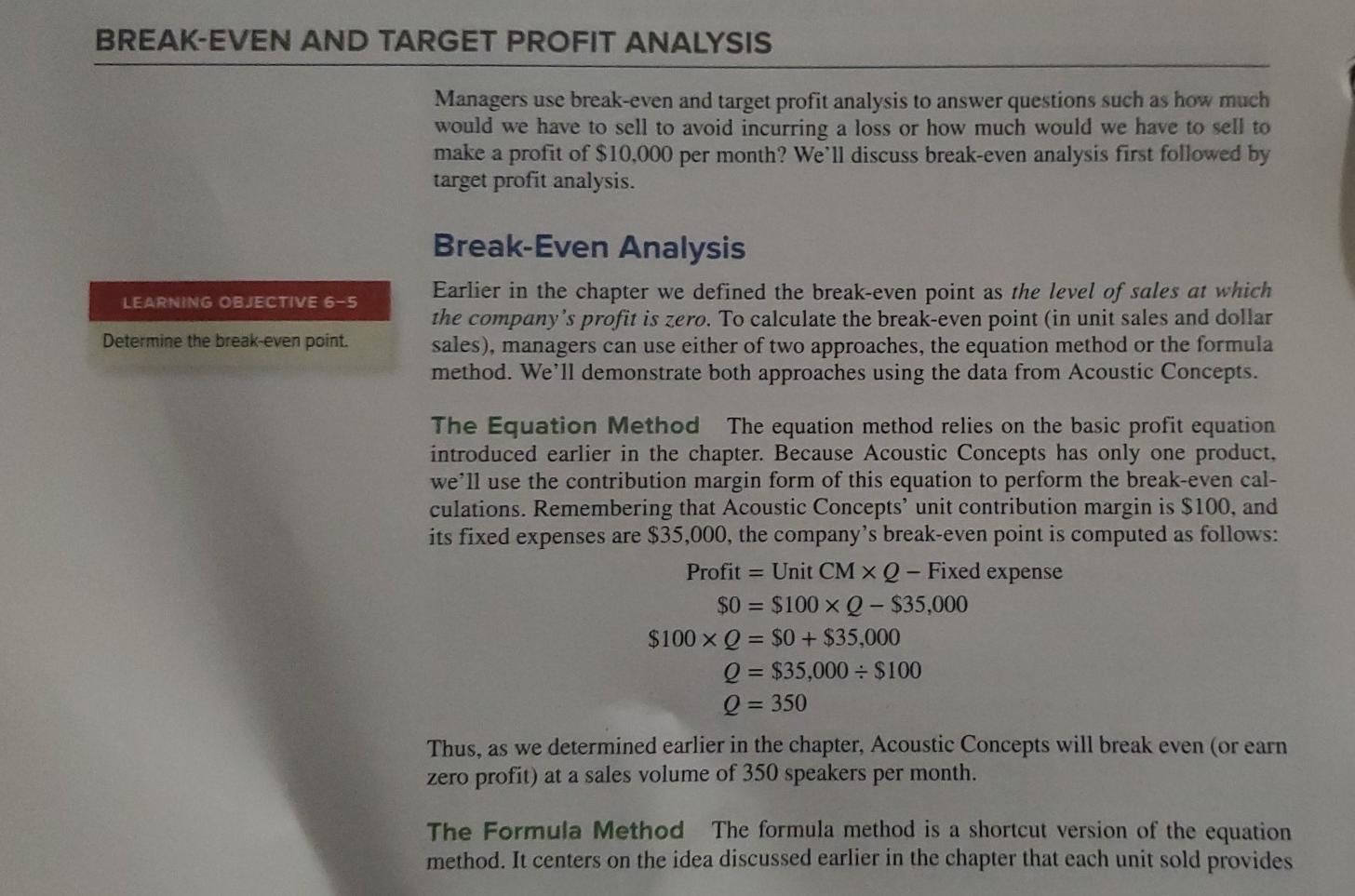

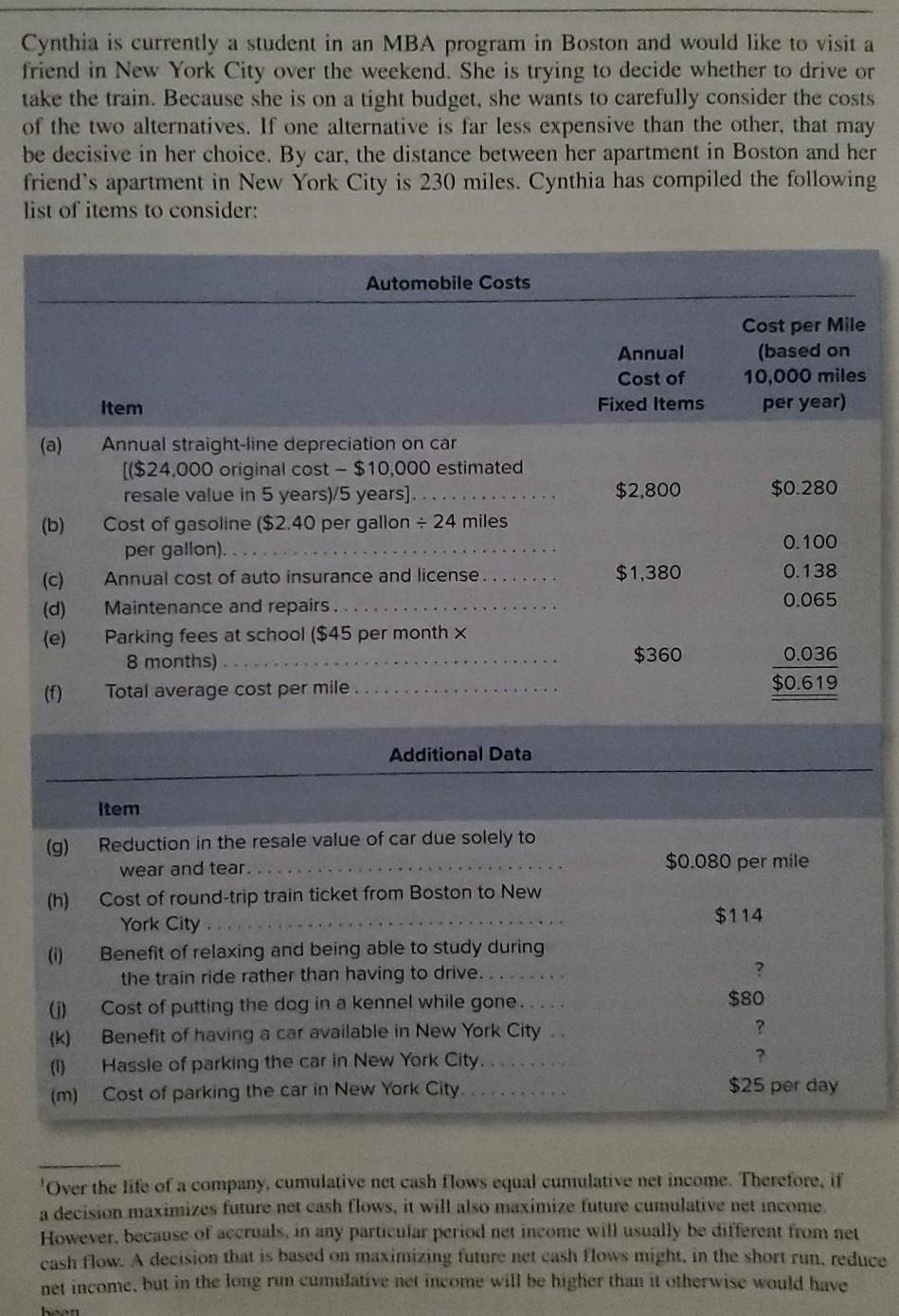

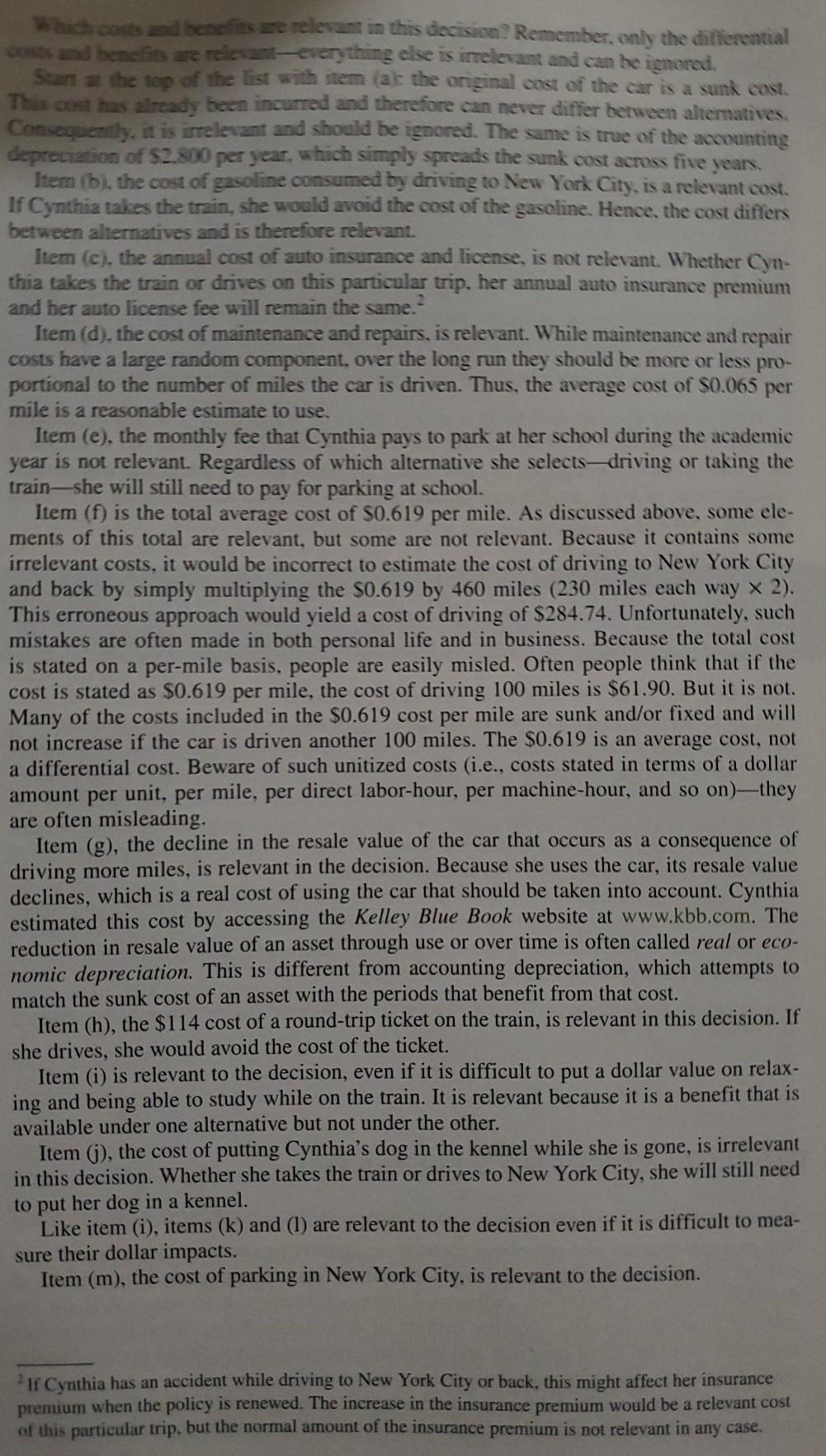

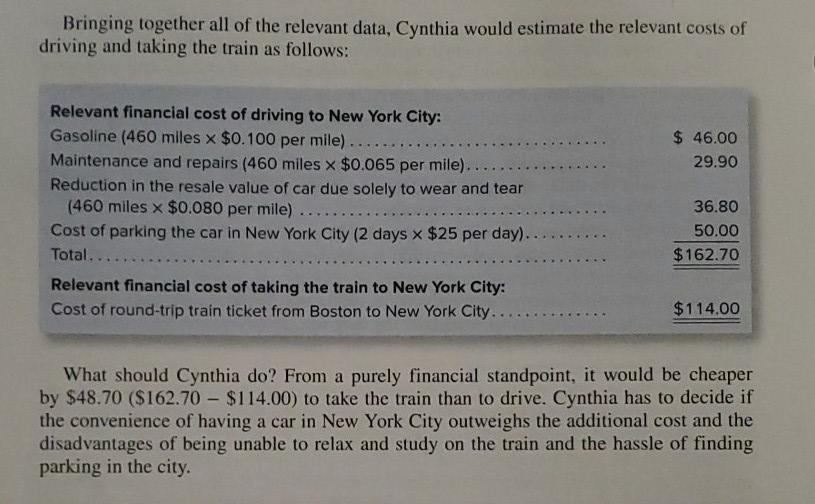

Required: For each of the following managerial accounting techniques, read the definition provided in your textbook. In your post, provide an example of a personal situation where you would benefit from use of each technique. 1. Break-even point (pgs. 220 - 221, 232) 2. Budget (pg. 334) 3. Differential Analysis: Relevant Costs & Benefits (pgs. 508 - 512) period Te illustrate with an extreme example, assume that Acoustic Concepts sells only one speler during a particular month. The company's income statement would appear Contribution Income Statement Sales of 1 Speaker Total $ 250 150 Per Unit $250 150 Sales (1 speaker) Variable expenses Contribution margin Foxed expenses Net operating loss $100 100 35,000 $ 34,900 For each additional speaker the company sells during the month, S100 more in contri- bution margin becomes available to help cover the fixed expenses. If a second speaker is sold, for example, then the total contribution margin will increase by $100 (to a total of $200) and the company's loss will decrease by $100. to S34,800: Contribution Income Statement Sales of 2 Speakers Total $ 500 300 Per Unit $250 150 Sales (2 speakers) Variable expenses Contribution margin Fored expenses $100 200 35.000 Net operating loss $(34,800) If enough speakers can be sold to generate $35,000 in contribution margin, then all of the fixed expenses will be covered and the company will break even for the month-that is, it will show neither profit nor loss but just cover all of its costs. To reach the break- even point, the company will have to sell 350 speakers in a month because each speaker sold yields $100 in contribution margin: Contribution Income Statement Sales of 350 Speakers Total $87.500 52,500 Per Unit $250 150 Sales (350 speakers) Variable expenses Contribution margin Fixed expenses $100 35.000 35.000 Net operating income $ 0 Computation of the break-even point is discussed in detail later in the chapter, for the moment, note that the break-even point is the level of sales at which profit is zero. Once the break-even point has been reached, net operating income will increase by the amount of the unit contribution margin for each additional unit sold. For example, if 351 speakers are sold in a month, then the net operating income for the month will be S100 because the company will have sold I speaker more than the number needed to break even: Contribution Income Statement Sales of 351 Speakers Per Unit $250 Sales (351 speakers) Variable expenses Contribution margin Fixed expenses Net operating income Total $87.750 52.650 35.100 35,000 150 $100 $ 100 If 352 speakers are sold (2 speakers above the break-even point), the net operat- ing income for the month will be $200. If 353 speakers are sold (3 speakers above the break-even point), the net operating income for the month will be $300, and so forth. To estimate the profit at any sales volume above the break-even point, multiply the number of units sold in excess of the break-even point by the unit contribution margin. The result represents the anticipated profits for the period. Or, to estimate the effect of a planned increase in sales on profits, simply multiply the increase in units sold by the unit contribution margin. The result will be the expected increase in profits. To illustrate, if Acoustic Concepts is currently selling 400 speakers per month and plans to increase sales to 425 speakers per month, the anticipated impact on profits can be computed as follows: Additional speakers to be sold Contribution margin per speaker Increase in net operating income 25 x $100 $2,500 These calculations can be verified as follows: Sales Volume 400 Speakers 425 Speakers Difference (25 Speakers) Per Unit $6,250 $250 $100,000 $106,250 150 Sales (@ $250 per speaker). Variable expenses (a $150 per speaker) Contribution margin Fixed expenses Net operating income $100 60,000 40,000 35,000 $ 5,000 63,750 42,500 35,000 $ 7,500 3,750 2,500 0 $2,500 To summarize, if sales are zero, the company's loss would equal its fixed expenses. Each unit that is sold reduces the loss by the amount of the unit contribution margin. Once the break-even point has been reached, each additional unit sold increases the com- pany's profit by the amount of the unit contribution margin. BREAK-EVEN AND TARGET PROFIT ANALYSIS Managers use break-even and target profit analysis to answer questions such as how much would we have to sell to avoid incurring a loss or how much would we have to sell to make a profit of $10,000 per month? We'll discuss break-even analysis first followed by target profit analysis. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 6-5 Break-Even Analysis Earlier in the chapter we defined the break-even point as the level of sales at which the company's profit is zero. To calculate the break-even point (in unit sales and dollar sales), managers can use either of two approaches, the equation method or the formula method. We'll demonstrate both approaches using the data from Acoustic Concepts. Determine the break-even point. The Equation Method The equation method relies on the basic profit equation introduced earlier in the chapter. Because Acoustic Concepts has only one product. we'll use the contribution margin form of this equation to perform the break-even cal- culations. Remembering that Acoustic Concepts' unit contribution margin is $100, and its fixed expenses are $35,000, the company's break-even point is computed as follows: Profit = Unit CM XQ - Fixed expense $0 = $100 x Q - $35,000 $100 x Q = $0 + $35,000 Q = $35,000 - $100 Q = 350 Thus, as we determined earlier in the chapter, Acoustic Concepts will break even (or earn zero profit) at a sales volume of 350 speakers per month. The Formula Method The formula method is a shortcut version of the equation method. It centers on the idea discussed earlier in the chapter that each unit sold provides n this chapter, we describe how organizations strive to achieve their financial goals by preparing budgets. A budget is a detailed plan for the future that is usu- Lally expressed in formal quantitative terms. Individuals sometimes create household budgets that balance their income and expenditures for food, clothing, housing, and so on while providing for some savings. Once the budget is established, actual spending is compared to the budget to make sure the plan is being followed. Companies use budgets in a similar way, although the amount of work and underlying details far exceed a per- sonal budget. WHY AND HOW DO ORGANIZATIONS CREATE BUDGETS? LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3-1 Understand why organizations budget and the processes they use to create budgets. Budgets are used for two distinct purposes-planning and control. Planning involves developing goals and preparing various budgets to achieve those goals. Control involves gathering feedback to ensure that the plan is being properly executed or modified as cir- cumstances change. To be effective, a good budgeting system must provide for both plan- ning and control. Good planning without effective control is a waste of time and effort. Advantages of Budgeting Organizations realize many benefits from budgeting, including: 1. Budgets communicate management's plans throughout the organization. 2. Budgets force managers to think about and plan for the future. In the absence of the necessity to prepare a budget, many managers would spend all of their time dealing with day-to-day emergencies. 3. The budgeting process provides a means of allocating resources to those parts of the organization where they can be used most effectively. 4. The budgeting process can uncover potential bottlenecks before they occur. 5. Budgets coordinate the activities of the entire organization by integrating the plans of its various parts. Budgeting helps to ensure that everyone in the organization is pulling in the same direction 6. Budgets define goals and objectives that can serve as benchmarks for evaluating subsequent performance. IN BUSINESS A Critical Prespective of How Companies Use Budgets Musa Images/Cetty Images RF Most, if not all companies operate in dynamic environments where the only constant is change The large majority of these companies also rely on annual budgets to manage themselves. The question becomes at what point do changes in the business environment render an annual budget obsolete? When 152 business professionals were asked this question 13% of them said their company's annual budget becomes obsolete before the new budget year begins. Another 46% of respondents sald the budget becomes obsolete before the second quarter of the bud- get year concludes, whereas 25% of those surveyed said the budget never becomes obsolete. Given that approximately 60% of respondents expressed concerns over obsolescence, it begged a related question for the 152 respondents: how many "what if" forecasts does your company prepare in response to changing market conditions About 20% of the respondents said their company did not evaluate any "what if" scenarios. Another 60% of respondents sald their employers evaluated no more than six "What ir scenarios Source: Merchant Kenneth A. "Companies Get Budgets All Wono." The Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2013. R5 To para destrament his chapter discusses what may be a manager's most important responsibility- making decisions. Examples of decisions include deciding what products to sell, distribution to use, and whether to accept special orders at special prices. Making such decisions is often a difficult task that is complicated by numerous alternatives and mas- sive amounts of data; however, in this chapter you will learn how to narrow your focus to the information that matters. DECISION MAKING: SIX KEY CONCEPTS There are six key concepts that you need to understand to make intelligent decisions. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 11-1 This section discusses each of those concepts and then concludes by introducing some Identity relevant and irrelevant additional terminology that was created to help you solve the exercises and problems at costs and benefits in a decision. the end of the chapter. Key Concept #1 Every decision involves choosing from among at least two alternatives. Therefore, the first step in decision making is to define the alternatives being considered. For example, if a company is deciding whether to make a component part or buy it from an outside sup- plier, the alternatives are make or buy the component part. Similarly, if a company is con- sidering discontinuing a particular product, the alternatives are keep or drop the product. Key Concept #2 Once you have defined the alternatives, you need to identify the criteria for choosing among them. The key to choosing among alternatives is distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant costs and benefits. Relevant costs and relevant benefits should be consid- ered when making decisions. Irrelevant costs and irrelevant benefits should be ignored when making decisions. This is an important concept for two reasons. First, being able to ignore irrelevant data saves decision makers tremendous amounts of time and effort. Second, bad decisions can easily result from erroneously including irrelevant costs and benefits when analyzing alternatives. Key Concept #3 The key to effective decision making is differential analysis focusing on the future costs and benefits that differ between the alternatives. Everything else is irrelevant and should be ignored. A future cost that differs between any two alternatives is known as a differential cost. ential costs are always relevant costs. Future revenue that differs between any two alternatives is known as differential revenue. Differential revenue is an example of a relevant benefit. The terms incremental cost and avoidable cost are often used to describe differential costs. An incremental cost is an increase in cost between two alternatives. For example, if you are choosing between buying the standard model or the deluxe model of your favorite automobile, the costs of the upgrades contained in the deluxe model are incre- mental costs. An avoidable cost is a cost that can be eliminated by choosing one alterna- tive over another. For example, assume that you have decided to watch a movie tonight: however, you are trying to choose between two alternatives-going to the movie theater or renting a movie. The cost of the ticket to get into the movie theater is an avoidable cost. You would avoid this cost by renting a movie. Similarly, the movie rental fee is an avoid- able cost because you could avoid it by going to the movie theater. Avoidable costs and incremental costs) are always relevant costs. Differential costs and benefits can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. While quali tative differences between alternatives can have an important impact on decisions, and therefore, should not be ignored; our goal in this chapter is to hone your quantitative analysis skills. Therefore, our primary focus will be on analyzing quantitative differential costs and benefits - those that have readily measurable impacts on future cash flows. Key Concept #4 Sunk costs are always irrelevant when choosing among alternatives. A sunk cost is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be changed regardless of what a manager decides to do. Sunk costs have no impact on future cash flows and they remain the same no matter what alternatives are being considered; therefore, they are irrelevant and should be ignored when making decisions. For example, suppose a company purchased a five-year-old truck for $12,000. The amount paid for the truck is a sunk cost because it has already been incurred and the transaction cannot be undone. The $12,000 paid for the truck is irrelevant in making decisions such as whether to keep, sell, or replace the truck. Furthermore, any accounting depreciation expense related to the truck is irrelevant in making decisions. This is true because accounting depreciation is a noncash expense that has no effect on future cash flows. It simply spreads the sunk cost of the truck over its useful life. Key Concept #5 Future costs and benefits that do not differ between alternatives are irrelevant to the deci- sion-making process. So, continuing with the movie example, assume that you plan to buy a Papa John's pizza after watching a movie. If you are going to buy the same pizza regardless of your movie watching venue, the cost of the pizza is irrelevant when choos- ing between the theater and the rental. The cost of the pizza is not a sunk cost because it has not yet been incurred. Nonetheless, the cost of the pizza is irrelevant to the choice of venue because it is a future cost that does not differ between the alternatives. Key Concept #6 Opportunity costs also need to be considered when making decisions. An opportunity cost is the potential benefit that is given up when one alternative is selected over another. For example, if you were considering giving up a high-paying summer job to travel over- seas, the forgone wages would be an opportunity cost of traveling abroad. Opportunity costs are not usually found in accounting records, but they are a type of differential cost that must be explicitly considered in every decision a manager makes. This chapter covers various decision contexts, such as keep or drop decisions, make or buy decisions, special order decisions, and sell or process further decisions. While tack- ling these diverse decision contexts may seem a bit overwhelming, keep in mind that they all share a unifying theme-choosing between alternatives based on their differential costs and benefits. To emphasize this common theme, many end-of-chapter exercises and problems that span a variety of learning objectives will often use the same terminology- financial advantage (disadvantage) - when asking you to choose between alternatives. For example, numerous exercises and problems will ask questions such as: 1. What is the financial advantage (disadvantage) of closing the store? 2. What is the financial advantage (disadvantage) of buying the component part from a supplier rather than making it? 3. What is the financial advantage (disadvantage) of accepting the special order? 4. What is the financial advantage (disadvantage) of further processing the intermediate product? In all of these various contexts, a financial advantage exists if pursuing an alterna- tive, such as closing a store or accepting a special order, passes the cost/benefit test. In Cynthia is currently a student in an MBA program in Boston and would like to visit a friend in New York City over the weekend. She is trying to decide whether to drive or take the train. Because she is on a tight budget, she wants to carefully consider the costs of the two alternatives. If one alternative is far less expensive than the other, that may be decisive in her choice. By car, the distance between her apartment in Boston and her friend's apartment in New York City is 230 miles. Cynthia has compiled the following list of items to consider: Automobile Costs Annual Cost of Fixed Items Cost per Mile (based on 10,000 miles per year) Item (a) $2,800 $0.280 (b) Annual straight-line depreciation on car [($24,000 original cost - $10,000 estimated resale value in 5 years)/5 years). Cost of gasoline ($2.40 per gallon - 24 miles per gallon) Annual cost of auto insurance and license Maintenance and repairs. Parking fees at school ($45 per month x 8 months) Total average cost per mile. $1,380 (c) (d) (e) 0.100 0.138 0.065 $360 0.036 $0.619 Additional Data Item (9) $0.080 per mile (h) $114 0 Reduction in the resale value of car due solely to wear and tear. Cost of round-trip train ticket from Boston to New York City Benefit of relaxing and being able to study during the train ride rather than having to drive.. Cost of putting the dog in a kennel while gone. Benefit of having a car available in New York City Hassle of parking the car in New York City. Cost of parking the car in New York City. ? $80 (1) (K) ? ? $25 per day (m) Over the life of a company, cumulative net cash flows equal cumulative net income. Therefore, if a decision maximizes future net cash flows, it will also maximize future cumulative net income However, because of accruals, in any particular period net income will usually be different from net cash flow. A decision that is based on maximizing futare net cash flows might, in the short run, reduce net income, but in the long run cumulative net income will be higher than it otherwise would have been Which costs and benefits are relevant in this decision. Remember, only the differential coses and benefits are relevant-everything else is irrelevant and can be ignored. Sun at the top of the list with item ialt the original cost of the car is a sunk cost. This cost has already been incurred and therefore can never differ between alternatives. Consequently, it is irrelevant and should be ignored. The same is true of the accounting depreciation of $2.800 per year, which simply spreads the sunk cost across five Item (b), the cost of gasoline consumed by driving to New York City, is a relevant cost. If Cynthia takes the train, she would avoid the cost of the gasoline. Hence, the cost differs between alternatives and is therefore relevant. Item (c), the annual cost of auto insurance and license, is not relevant. Whether Cyn- thia takes the train or drives on this particular trip. her annual auto insurance premium and her auto license fee will remain the same. Item (d), the cost of maintenance and repairs, is relevant. While maintenance and repair costs have a large random component over the long run they should be more or less pro- portional to the number of miles the car is driven. Thus, the average cost of $0.065 per mile is a reasonable estimate to use. Item (e), the monthly fee that Cynthia pays to park at her school during the academic year is not relevant. Regardless of which alternative she selects-driving or taking the train-she will still need to pay for parking at school. Item (f) is the total average cost of $0.619 per mile. As discussed above, some ele- ments of this total are relevant, but some are not relevant. Because it contains some irrelevant costs, it would be incorrect to estimate the cost of driving to New York City and back by simply multiplying the $0.619 by 460 miles (230 miles each way x 2). This erroneous approach would yield a cost of driving of $284.74. Unfortunately, such mistakes are often made in both personal life and in business. Because the total cost is stated on a per-mile basis. people are easily misled. Often people think that if the cost is stated as $0.619 per mile, the cost of driving 100 miles is $61.90. But it is not. Many of the costs included in the $0.619 cost per mile are sunk and/or fixed and will not increase if the car is driven another 100 miles. The $0.619 is an average cost, not a differential cost. Beware of such unitized costs (i.e., costs stated in terms of a dollar amount per unit, per mile, per direct labor-hour, per machine-hour, and so on)they are often misleading. Item (g), the decline in the resale value of the car that occurs as a consequence of driving more miles, is relevant in the decision. Because she uses the car, its resale value declines, which is a real cost of using the car that should be taken into account. Cynthia estimated this cost by accessing the Kelley Blue Book website at www.kbb.com. The reduction in resale value of an asset through use or over time is often called real or eco- nomic depreciation. This is different from accounting depreciation, which attempts to match the sunk cost of an asset with the periods that benefit from that cost. Item (h), the $114 cost of a round-trip ticket on the train, is relevant in this decision. If she drives, she would avoid the cost of the ticket. Item (i) is relevant to the decision, even if it is difficult to put a dollar value on relax- ing and being able to study while on the train. It is relevant because it is a benefit that is available under one alternative but not under the other. Item (i), the cost of putting Cynthia's dog in the kennel while she is gone, is irrelevant in this decision. Whether she takes the train or drives to New York City, she will still need to put her dog in a kennel. Like item (i), items (k) and (l) are relevant to the decision even if it is difficult to mea- sure their dollar impacts. Item (m), the cost of parking in New York City, is relevant to the decision. If Cynthia has an accident while driving to New York City or back, this might affect her insurance premium when the policy is renewed. The increase in the insurance premium would be a relevant cost of this particular trip, but the normal amount of the insurance premium is not relevant in any case. Bringing together all of the relevant data, Cynthia would estimate the relevant costs of driving and taking the train as follows: $ 46.00 29.90 Relevant financial cost of driving to New York City: Gasoline (460 miles x $0.100 per mile).... Maintenance and repairs (460 miles x $0.065 per mile)... Reduction in the resale value of car due solely to wear and tear (460 miles x $0.080 per mile) .. Cost of parking the car in New York City (2 days

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts