Question

Caesar Group, a professional IT services firm, has competed in the Dutch IT market since 1993 with a workforce close to 300 employees. The company's

Caesar Group, a professional IT services firm, has competed in the Dutch IT market since 1993 with a workforce close to 300 employees. The company's initial value proposition was providing its customers with qualified human capacity (body-shopping) at a low hourly or daily rate. Caesar always enjoyed extremely high satisfaction and loyalty rates among its employees, thanks to the company's sound, continuous commitment to people's professional and personal development. Such strong internal brand equity served Caesar very well in attracting young talent from the job market, despite limited brand awareness in the customer market. In 2001, Caesar's reaction to the IT bubble and to the increasing commoditization of the body-shopping service was twofold. On the one hand, the company progressively formulated a brand new value proposition, so called TimeValue projects, consisting of the delivery of complete IT projects, guaranteed on time and within budget, at a premium price. On the other, Caesar understood it had to reposition its body-shopping division upward by increasing the quality profile of what it offered.

In 2005, Caesar launched TimeValueProjects in the marketplace and marketed two value propositions (body-shopping and TimeValue projects) using integrated organizational routines under one brand name. This led to three main problems that produced significant stress and frustration within the company management. First of all, the integrated brand name led to a diffuse marketing proposition towards prospective customers. Existing customers had trouble in perceiving the added value of the TimeValue projects division over and above the body-shopping division. New customers for body-shopping were attracted mainly by the TimeValue projects' proposition. The second problem concerned sales. Each Sales Manager encountered difficulties in selling the two products within the same portfolio. The sales process for body-shopping was a short "push" process, while the sales process for projects was a long "pull" cycle. In addition, Sales and Operations managers in body-shopping typically focused on "number of hours", whereas in order to sell TimeValue projects, they had to shift focus to timely delivery.

In 2008, despite the fact that three years had passed since the TimeValue market launch, Caesar was not satisfied with sales results and was still devoting resources to understanding how to convert the interest in TimeValue projects as a proposition into real sales. Faced with these troubles, Hans van der Kooij, founder and CEO of the company, was wondering about the strategic decisions to take in the next few years.

There are two main types of services in the Dutch IT market: IT outsourcing and professional IT services. The Caesar Group offered only the second type of service, either at an hourly or daily rate (often referred to as "body-shopping") or as a project for a fixed price. Typically, in body-shopping, the scope of the IT problem is defined by the customer, while in TimeValue Projects, the supplier co-defines the scope with the customer.

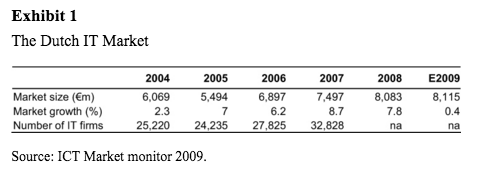

According to the Dutch research agency ICT ~ Office,1 the Dutch IT Software and Services Industry grew by 7.8% in 2008 achieving a market size of 8.1bn. 2009 was expected to produce a radically different picture due to the economic crisis. Overall, the sector was expected to grow by only 0.4%. The Dutch market was pretty fragmented, with approximately 30,000 different suppliers (Exhibit 1).

The "Human" Factor

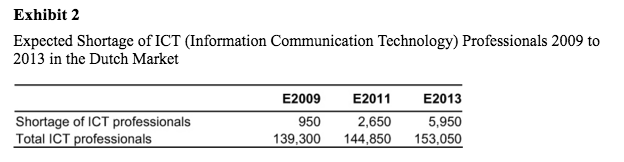

Human talent - employees with the required technical knowledge and expertise - was absolutely pivotal in this market. Market players relied on the continued service of qualified employees and high staff turnover was very costly. The increasing shortage of good ICT (Information Communication Technology) professionals was a concern for the industry in the Netherlands. ICT companies were increasingly facing the problem of barely being able to accept contracts due to the acute shortage of staff. This was especially true for smaller startups that had not yet established brand equity in the labor market. Overall, the number of new students in Dutch colleges and universities was dwindling and prospects for the incoming years weren't promising. It was expected that the shortage of highly qualified ICT professionals would have increased to nearly 6,000 by 2013. It was a challenge to address these shortages and the fight for the most talented IT professionals was tough (Exhibit 2).

Competition

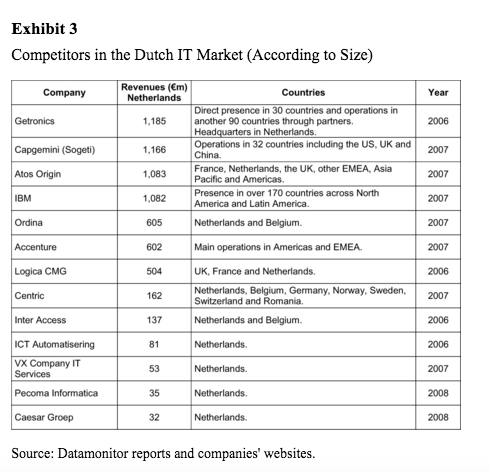

The IT services industry was quite fragmented, with large multinational companies competing alongside small players. The upper end of the market included global services giants that primarily served multinational companies and government agencies, such as Accenture, AtosOrigin, Cap Gemini, Getronics, IBM, and LogicaCMG. The opposite end of the market was fairly fragmented with local and regional firms serving the needs of domestic multinationals and small businesses, such as Ordina, VX Company, ICT Automatisering, Centric, Inter Access, and Pecoma Informatica (Exhibit 3).

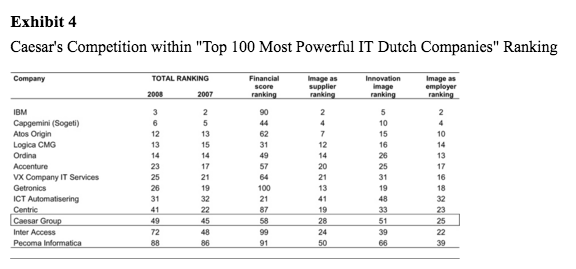

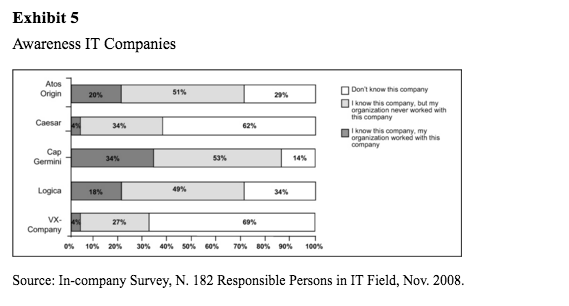

Exhibit 4 shows the position occupied by each of the above mentioned IT companies in the Netherlands, according to the trade journal Computable. IT companies were valued according to various factors such as financial strength, innovation power and image as supplier and as employer. The overall position of any company on the "Top 100 most powerful IT Dutch companies" ranking was obtained by aggregating the scores on the individual dimensions. Overall Caesar ranked number 45 in 2007 and number 49 in 2008 out of the 100 top IT Dutch companies. Compared to its main competitors, Caesar enjoyed a better image as a supplier and as an employer, rather than its image from the financial perspective. An incompany survey also highlighted the weakness of Caesar in terms of brand awareness (Exhibit 5). Large firms such as Atos Origin, Cap Gemini and Logica enjoyed much higher brand awareness than Caesar, or other small firms, such as VX Company.

The Customer

Customers of IT application software services generally expressed three primary needs: 1) new applications, 2) alterations to existing applications, and 3) maintenance and support for existing applications. The problem definition and the governance over these activities could lie with the customer (body-shopping) or with the supplier (projects and maintenance service level agreements). In the Dutch application software market, in which Caesar was active, body-shopping was a commodity in the mind of the customer, while projects and maintenance were perceived as added value activities.

The decision-making unit for the purchase of body-shopping contracts consisted of the IT manager and the Purchase manager. Typically, the IT manager weighed in heavily on supplier selection and the Purchasing manager weighed in heavily on contract details and price. A significant group of customers defined a threshold which the price could not exceed. On the other hand, the decision makers for IT projects consisted of the business unit or functional manager, IT manager, CFO and Purchasing manager. Often, the business unit or functional manager expressed a need for application software in a certain domain (e.g. sales force automation, lead follow-up) to the IT manager. The CFO was usually involved as IT projects on average were large and required a new budget. Typically, the business unit manager weighed in equally to the IT manager on supplier selection. Contracts with large customers were often secured through a bidding process.

In general, IT projects had a long purchasing cycle: from several months to a year from the first signs of interest was not uncommon. Projects also had a relatively long delivery cycle, again with a year or more not being exceptional. Body-shopping in contrast had short purchasing cycles. Often, there was an immediate need with a customer that had to be fulfilled in two weeks or so. There was a wide variation in the duration of body-shopping contracts. Most customers shortened them to only a couple of months or demanded short termination periods. In times of strong economic growth, body-shopping contracts were often automatically renewed and could persist for a very long time (over 5 years was common). In times of economic downturn, customers tended to terminate contracts in large numbers and / or demand price reductions.

The Caesar Group

How it All Started and Company Values

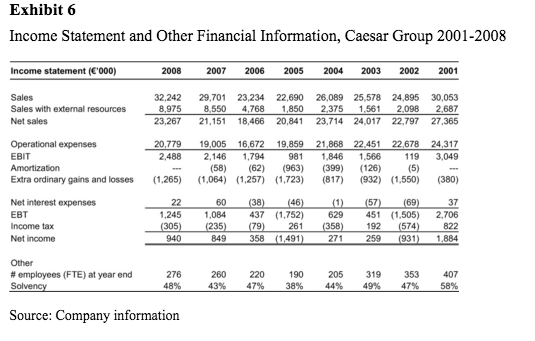

Founded by Hans van der Kooij, the Caesar Group had operated since 1993 in the Dutch Professional IT Services Market. As of 2008, the company achieved sales of 32m with just under 300 employees (Exhibit 6).

In the first years, Caesar operated as a temporary IT agency (very similar to EDS), which is commonly referred to in the IT industry as a "body-shopper". The company's technological expertise included .NET, Java, Oracle, Progress and Microsoft Infrastructure, Business Intelligence and Process Optimisation. Throughout the 90s, Caesar pursued a cost leadership strategy with the marketing proposition of "good people at a reasonable price" (almost 60% cheaper than market average). As a matter of fact, Hans van der Kooij had been inspired by the Wal-Mart commitment to share with consumers the benefits derived from efficient operations through prices as low as possible. He founded Caesar with the vision of implementing the same business model in IT. From the very beginning, the company committed itself to Total Quality Management and invested considerable amounts of money into technology and knowledge gathering. This policy enabled Caesar to deliver good quality knowledge at a convenient price in a sustainable fashion.

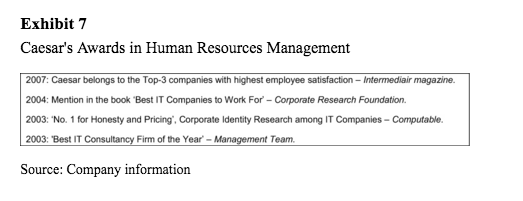

Deeply rooted in the founder's belief that success in service businesses depends on people, Caesar's Human Resources policy always aimed at developing employees' competences and at taking care of the work-life balance of employees and of their families. For instance, the so-called "CareerValue" track consisted of continuous career development for employees by means of high-profile projects and individual, well-defined two year step-by-step career plans. Caesar also had its own in-company gym and day nursery and offered a sabbatical leave at the company's expense for workers employed for more than seven years. In addition, Caesar offered employees custom-made fringe benefits, so-called "Flex Package" (i.e. more holidays, paying for childcare, etc.). As a result, employees' satisfaction and loyalty rates were outstanding and the company had an impressive awards track record as best employer in the Netherlands (Exhibit 7). This status has served the company very well in recruiting. In the Dutch IT labor market, a strong brand name in the eyes of future employees was absolutely critical to a firm's later success. For start-ups, the lack of such strong brand equity to future employees was one of the most significant hurdles.

Thanks to Hans van der Kooij's inspirational, and in some ways paternalistic, leadership, employees have identified with the firm to a great extent. Most, if not all, employees shared a common value system and had a very strong sense of belonging to the Caesar Group. However this shared culture among Caesar employees had not led to "groupthinking". In fact, what defined the company culture most was the challenging of commonly held ideas and the eternal "why" question that popped up in any managerial meeting.

The 2001 Bubble

In 2001, Caesar at first thought the crisis was going to be an opportunity for a cost leader rather than a threat. Management expected that Caesar's gain in market share, due to an increase in competitiveness, would more than compensate for the market shrinkage, which was forecasted around minus 5%. Unfortunately the magnitude of the crisis was in reality greater than initially expected, around minus 40%. Even upper end players, such as Logica CMG, lowered prices below costs in order not to lose customers, therefore nullifying Caesar's competitive advantage.

In the years following the crisis, the industry underwent a consolidation process. Many companies went bankrupt or were taken over by other companies. Caesar received several acquisition offers in 2002 as well, but Hans van der Kooij decided not to sell the company despite sales suffering and the layoff of employees. However, management realized that the cost leadership strategy was not sustainable anymore and felt a strategic change was urgent.

Focus on ROI of IT Application Systems

The strategic change toward a "value" strategy at first resulted in a focus on the Return On Investment firms obtained on application software. Caesar decided to organize its fee structure based on the savings the customers would enjoy thanks to the implementation of their application software. However, this proposition was not sustainable for two reasons. First, Caesar underestimated the management attention this strategy needed on the internal side, hurting profitability. Second, they did not have complete control over the customer's processes (such as project management, business need definition, and implementation), leading to a lack of ROI for the customer, through the customer's own doing.

Towards Operational Excellence

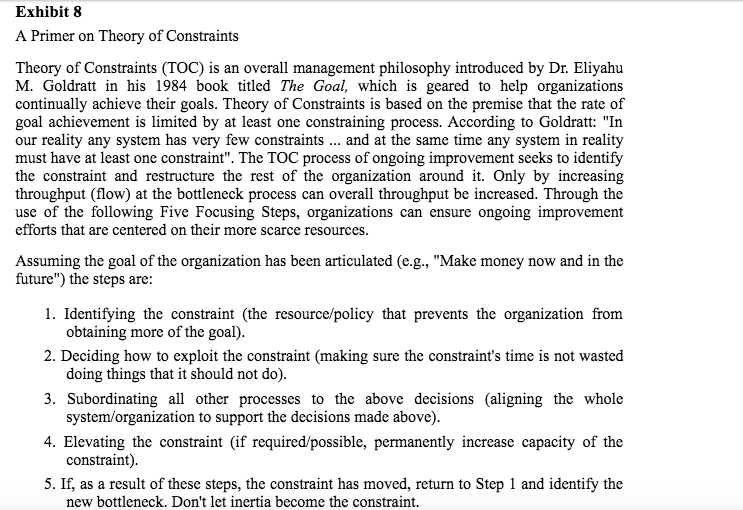

The company underwent another radical change in 2003 and extended its "body-shopping" offer to the execution and management of IT software development projects (custom-made software). Between 2003 and 2005, Caesar developed a project methodology - TimeValue -to deliver IT software development projects on time and within budget. This project methodology was embedded in Goldratt's Theory of Constraints method (Exhibit 8 offers a primer on TOC). In fact, Caesar was the first company around the globe that applied the TOC method to a service business. Through TOC, Caesar was able to identify why projects were always late, over budget and often out of scope and to think about viable solutions for these issues. As a research study demonstrated, these matters were relevant concerns. According to a 2004 report published by the Standish Group with data from more than 50,000 projects, 82% of projects deliver late, 53% of the projects exceed their budget (on average, 1.9 times), 71% do not fulfill expectations.

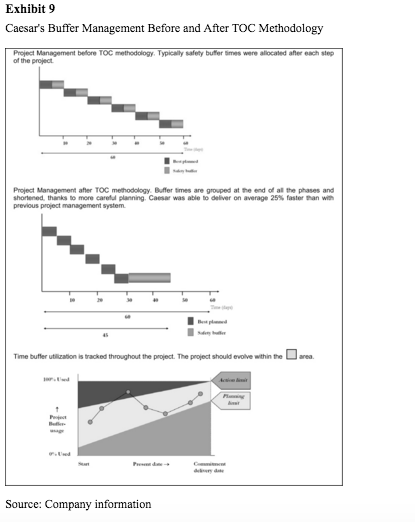

Caesar also identified that there was a critical mismatch between customer and provider. Given that the service provider was paid on an hourly base, there was a strong incentive in delaying the project and delivering late, which generated frustration on the client's side. Caesar came to realize that such a mismatch could be fixed through aligning the goals of customer and provider by choosing a pricing strategy that guaranteed "fixed time and fixed budget type" of agreement with clients, the so called TimeValue projects. In the case of a project delivery being delayed, clients would only pay Caesar half the price. Buffer time management was critical in building Caesar's operational advantage and in implementing state-of-the art TOC method in the IT services (Exhibit 9).

The Struggle to Turn Operational Excellence into Sales and Profits

In 2005, Caesar proceeded with the market launch of its TimeValue project proposition, expecting it to take off immediately. However, by the end of 2006, the results were disappointing and sales did not reach these sky-high expectations. Sales of TimeValue projects did not pick up, nor did profits, and Caesar started losing sales in body-shopping because of the excessive focus on TimeValue projects. The origin of the launch failure lay mainly in three interconnected problems.

A first problem was the brand association customers made with the name Caesar and the change in value proposition that the company aimed to deliver to its clients. Caesar sold one clearly differentiated product with high methodological excellence (TimeValue projects) and one commodity product without a unique selling proposition (IT body shopping) under the same brand name. While Caesar was able to raise interest with potential customers in TimeValue workshops (Exhibit 10), they were not able to make customers comfortable to the extent that initial interest could be converted into a sale. Hans Nijholt, Managing Director of the Projects Division, recalled: "We had problems in getting enough contracts and penetrating the market. (...). We clearly saw a lot of new prospects in our sales but we were still not able to find the way to convert the interest for our proposition into sales."

Connected to the brand confusion, a second problem was the sales process that Caesar employed. The sales process for body-shopping was a short "push" process (average length 2-4 weeks), while the sales process for projects was a long "pull" cycle (average length between 3 and 6 months). The body-shopping sales process often started with a clear customer request for a specific IT capability and capacity, while TimeValue projects often started with raising the interest of the potential client through referencing among customers and TimeValue workshops. While the different steps in the sales process of TimeValue projects (Exhibit 11) were configured in detail by the Sales manager, Luc Spaas, Caesar approached clients in an integrated fashion. Therefore each Sales Representative had both products in the selling portfolio. To make matters worse, sales representatives for the body-shopping proposition seemed to use the appeal of the TimeValue method to get a foot in the door with potential customers to consequently make body-shopping deals. According to Lars de Laat, Value Manager for TimeValue projects: "Many of our sales people still had difficulties in understanding the TimeValue projects and in selling them. People working on hours just work differently from people working to an end date. (...)." Landing body-shopping deals also required completely different sales capabilities than landing TimeValue project deals. The mentality shift from a focus on "number of hours sold" versus "delivery on time and within budget" required alignment in people's attitudes and in performance measures that hadn't been dealt with before by Caesar. Hans Nijholt recalled: "Selling body-shopping hours is completely different from selling an LT project. We definitely underestimated the different skills and the type of behavior needed to conduct this type of sale: selling a house is more difficult than selling a carpet. Furthermore we didn't change the measures by which we would assess the performance of the sales force... and, people behave in the way you measure them."

A third problem was frustration in the service delivery process. The situation progressively led to internal struggles and tension among talented employees. Management couldn't help feeling that people working on TimeValue projects were in a different (higher) league than those working on the body-shopping business. In Hans van der Kooij's words it seemed as if "TimeValue projects were the ideal division to work for in Caesar." Internally, operations were repeatedly frustrated by the lack of focus on either body-shopping or TimeValue projects. Furthermore the Human Resource people managing the talent pool were always confronted with the dilemma on whether to "sell" the best people "as bodies" or to keep them free for a potential upcoming TimeValue project, taking the very likely risk of keeping the best talents idle for many months. Here is management's take, in Lars de Laat's words, on the internal situation as of 2007: "We were two years down the road, and we were still not successful! Not only did we not succeed in growing the business, but also people in the company were fighting each other as if they had different goals. Many managers were feeling uncomfortable; they felt they had a foot in each camp, as if they had to choose between the two and they didn't know how to pick".

Research Plan

Facing this struggle, Marjon Vermeulen, Caesar's VP of Marketing, spearheaded a taskforce to understand and address the first two marketing problems described above. She decided to analyze customer behavior in more detail to clarify customers' needs and to identify a way to address them. With the help of the Marketing Technology and Innovation Institute (www.mti2.eu), an external marketing consultant, Caesar ran the following customer research.

First, Caesar conducted qualitative interviews with customers. The finding was that Caesar could really differentiate itself on its TimeValue projects business. Marjon Vermeulen recalled: "Some customers were totally impressed by our performance in TimeValue projects and described them as "Too good to be true" and "You'll only believe it when you see it"." For its body-shopping business, at first qualitative research did not hint at any differentiator in Caesar's offering.

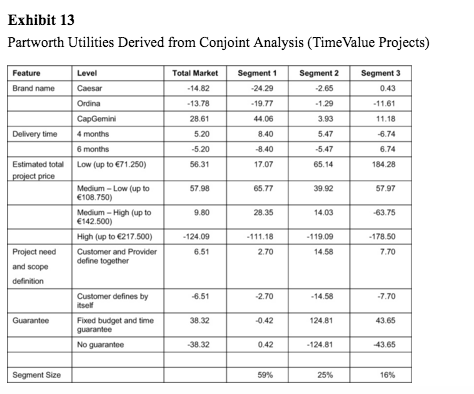

Consequently, the firm decided to quantitatively test the proposition "a deal is a deal" for TimeValue projects and its attributes in a conjoint analysis (Exhibit 12offers a primer on conjoint analysis). Such conjoint analysis allowed Caesar to discern the price point which it could target and the size of the potential target market. The conjoint analysis (see Exhibit 13 for the raw partworths across customer segments) led to the following conclusions: 1) the three most important attributes were price, time and budget guarantee, and the brand name in that order, while delivery speed and methodology were found not to be crucial; 2) customers could be clustered in three main segments: Segment 1 (59% of the market) valued the brand name of a supplier and was less price-sensitive (even associating less utility to a low priced supplier than to a medium priced supplier)2; Segment 2 (25% of the market) valued a time and budget guarantee very highly and was moderately price sensitive; Segment 3 (16% of the market) was very price sensitive. A large scale survey further supported the relative sizes of the above target segments. In addition, from a correlation of the segments that were derived from the conjoint analysis for projects, Caesar learnt that IT managers in the guarantee segment were frustrated by projects running over time to a greater extent than IT managers in other segments and they were in general also more entrepreneurial. According to Marjon Vermeulen: "The conjoint study represented a major turning point for marketing projects. We understood we had a specific customer segment to target: the so-called "entrepreneurial" IT Manager. This segment was strongly interested in the Project value proposition and represented a quarter of the potential customer base."

Convinced by the power of conjoint analysis, Caesar moved on to conceptualize potential differentiators for the body-shopping business. Through internal brainstorming sessions, a lead user customer group and qualitative interviews with IT managers, the company derived five potential sources of differentiation:

Whether the supplier focused on specific applications or rather served as an integrator across applications.

Whether the supplier promptly delivered resumes of IT professionals.

Whether the supplier knew the organizational routines of the firm, for instance through prior experience with that firm or with other firms in the same industry.

Whether the supplier offered a "no questions asked" satisfaction guarantee.

Whether the supplier had loyalty programs rewarding long customer relationships.

In an exploration phase, Caesar decided to test whether any of the key differentiators above could match with limited price sensitivity of customers. The results of the conjoint are reported inExhibit 14. The main conclusions were: (1) A strong satisfaction guarantee was the strongest differentiator, followed by prior knowledge of organizational processes; (2) four main segments existed: Segment 1 (15% of the market) cared very much about prior knowledge of organizational processes; Segment 2 (8% of the market) was very price sensitive; Segment 3 (25% of the market) cared about the satisfaction guarantee; Segment 4 (52% of the market) was not very specific about what it looked for exactly. The latter segment confirmed that the market for body-shopping was pretty much a commodity market. On the basis of this conjoint study, Caesar started an implementation process for a full service satisfaction guarantee on its body-shopping contracts and decided also to initiate a relationship management program.

Issues to be Resolved

After gaining the above customer inputs, Marjon Vermeulen brought together the main decision-makers in the firm to resolve the issues Caesar was facing. The critical matters she put on the agenda were the following:

What are the core learnings from the customer research that Caesar has conducted?

Can the two (TimeValue projects versus body-shopping) value propositions be successful in the same firm? Why? Why not?

Is there some better structure for Caesar that would serve the overall firm goals, but also make the two units improve further both in profits and sales?

How should the brand be positioned? Can the same brand be used to market the different value propositions?

Caesar Group, a professional IT services firm, has competed in the Dutch IT market since 1993 with a workforce close to 300 employees. The company's initial value proposition was providing its customers with qualified human capacity (body-shopping) at a low hourly or daily rate. Caesar always enjoyed extremely high satisfaction and loyalty rates among its employees, thanks to the company's sound, continuous commitment to people's professional and personal development. Such strong internal brand equity served Caesar very well in attracting young talent from the job market, despite limited brand awareness in the customer market. In 2001, Caesar's reaction to the IT bubble and to the increasing commoditization of the body-shopping service was twofold. On the one hand, the company progressively formulated a brand new value proposition, so called TimeValue projects, consisting of the delivery of complete IT projects, guaranteed on time and within budget, at a premium price. On the other, Caesar understood it had to reposition its body-shopping division upward by increasing the quality profile of what it offered.

In 2005, Caesar launched TimeValueProjects in the marketplace and marketed two value propositions (body-shopping and TimeValue projects) using integrated organizational routines under one brand name. This led to three main problems that produced significant stress and frustration within the company management. First of all, the integrated brand name led to a diffuse marketing proposition towards prospective customers. Existing customers had trouble in perceiving the added value of the TimeValue projects division over and above the body-shopping division. New customers for body-shopping were attracted mainly by the TimeValue projects' proposition. The second problem concerned sales. Each Sales Manager encountered difficulties in selling the two products within the same portfolio. The sales process for body-shopping was a short "push" process, while the sales process for projects was a long "pull" cycle. In addition, Sales and Operations managers in body-shopping typically focused on "number of hours", whereas in order to sell TimeValue projects, they had to shift focus to timely delivery.

In 2008, despite the fact that three years had passed since the TimeValue market launch, Caesar was not satisfied with sales results and was still devoting resources to understanding how to convert the interest in TimeValue projects as a proposition into real sales. Faced with these troubles, Hans van der Kooij, founder and CEO of the company, was wondering about the strategic decisions to take in the next few years.

There are two main types of services in the Dutch IT market: IT outsourcing and professional IT services. The Caesar Group offered only the second type of service, either at an hourly or daily rate (often referred to as "body-shopping") or as a project for a fixed price. Typically, in body-shopping, the scope of the IT problem is defined by the customer, while in TimeValue Projects, the supplier co-defines the scope with the customer.

According to the Dutch research agency ICT ~ Office,1 the Dutch IT Software and Services Industry grew by 7.8% in 2008 achieving a market size of 8.1bn. 2009 was expected to produce a radically different picture due to the economic crisis. Overall, the sector was expected to grow by only 0.4%. The Dutch market was pretty fragmented, with approximately 30,000 different suppliers (Exhibit 1).

The "Human" Factor

Human talent - employees with the required technical knowledge and expertise - was absolutely pivotal in this market. Market players relied on the continued service of qualified employees and high staff turnover was very costly. The increasing shortage of good ICT (Information Communication Technology) professionals was a concern for the industry in the Netherlands. ICT companies were increasingly facing the problem of barely being able to accept contracts due to the acute shortage of staff. This was especially true for smaller startups that had not yet established brand equity in the labor market. Overall, the number of new students in Dutch colleges and universities was dwindling and prospects for the incoming years weren't promising. It was expected that the shortage of highly qualified ICT professionals would have increased to nearly 6,000 by 2013. It was a challenge to address these shortages and the fight for the most talented IT professionals was tough (Exhibit 2).

Competition

The IT services industry was quite fragmented, with large multinational companies competing alongside small players. The upper end of the market included global services giants that primarily served multinational companies and government agencies, such as Accenture, AtosOrigin, Cap Gemini, Getronics, IBM, and LogicaCMG. The opposite end of the market was fairly fragmented with local and regional firms serving the needs of domestic multinationals and small businesses, such as Ordina, VX Company, ICT Automatisering, Centric, Inter Access, and Pecoma Informatica (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 4 shows the position occupied by each of the above mentioned IT companies in the Netherlands, according to the trade journal Computable. IT companies were valued according to various factors such as financial strength, innovation power and image as supplier and as employer. The overall position of any company on the "Top 100 most powerful IT Dutch companies" ranking was obtained by aggregating the scores on the individual dimensions. Overall Caesar ranked number 45 in 2007 and number 49 in 2008 out of the 100 top IT Dutch companies. Compared to its main competitors, Caesar enjoyed a better image as a supplier and as an employer, rather than its image from the financial perspective. An incompany survey also highlighted the weakness of Caesar in terms of brand awareness (Exhibit 5). Large firms such as Atos Origin, Cap Gemini and Logica enjoyed much higher brand awareness than Caesar, or other small firms, such as VX Company.

The Customer

Customers of IT application software services generally expressed three primary needs: 1) new applications, 2) alterations to existing applications, and 3) maintenance and support for existing applications. The problem definition and the governance over these activities could lie with the customer (body-shopping) or with the supplier (projects and maintenance service level agreements). In the Dutch application software market, in which Caesar was active, body-shopping was a commodity in the mind of the customer, while projects and maintenance were perceived as added value activities.

The decision-making unit for the purchase of body-shopping contracts consisted of the IT manager and the Purchase manager. Typically, the IT manager weighed in heavily on supplier selection and the Purchasing manager weighed in heavily on contract details and price. A significant group of customers defined a threshold which the price could not exceed. On the other hand, the decision makers for IT projects consisted of the business unit or functional manager, IT manager, CFO and Purchasing manager. Often, the business unit or functional manager expressed a need for application software in a certain domain (e.g. sales force automation, lead follow-up) to the IT manager. The CFO was usually involved as IT projects on average were large and required a new budget. Typically, the business unit manager weighed in equally to the IT manager on supplier selection. Contracts with large customers were often secured through a bidding process.

In general, IT projects had a long purchasing cycle: from several months to a year from the first signs of interest was not uncommon. Projects also had a relatively long delivery cycle, again with a year or more not being exceptional. Body-shopping in contrast had short purchasing cycles. Often, there was an immediate need with a customer that had to be fulfilled in two weeks or so. There was a wide variation in the duration of body-shopping contracts. Most customers shortened them to only a couple of months or demanded short termination periods. In times of strong economic growth, body-shopping contracts were often automatically renewed and could persist for a very long time (over 5 years was common). In times of economic downturn, customers tended to terminate contracts in large numbers and / or demand price reductions.

The Caesar Group

How it All Started and Company Values

Founded by Hans van der Kooij, the Caesar Group had operated since 1993 in the Dutch Professional IT Services Market. As of 2008, the company achieved sales of 32m with just under 300 employees (Exhibit 6).

In the first years, Caesar operated as a temporary IT agency (very similar to EDS), which is commonly referred to in the IT industry as a "body-shopper". The company's technological expertise included .NET, Java, Oracle, Progress and Microsoft Infrastructure, Business Intelligence and Process Optimisation. Throughout the 90s, Caesar pursued a cost leadership strategy with the marketing proposition of "good people at a reasonable price" (almost 60% cheaper than market average). As a matter of fact, Hans van der Kooij had been inspired by the Wal-Mart commitment to share with consumers the benefits derived from efficient operations through prices as low as possible. He founded Caesar with the vision of implementing the same business model in IT. From the very beginning, the company committed itself to Total Quality Management and invested considerable amounts of money into technology and knowledge gathering. This policy enabled Caesar to deliver good quality knowledge at a convenient price in a sustainable fashion.

Deeply rooted in the founder's belief that success in service businesses depends on people, Caesar's Human Resources policy always aimed at developing employees' competences and at taking care of the work-life balance of employees and of their families. For instance, the so-called "CareerValue" track consisted of continuous career development for employees by means of high-profile projects and individual, well-defined two year step-by-step career plans. Caesar also had its own in-company gym and day nursery and offered a sabbatical leave at the company's expense for workers employed for more than seven years. In addition, Caesar offered employees custom-made fringe benefits, so-called "Flex Package" (i.e. more holidays, paying for childcare, etc.). As a result, employees' satisfaction and loyalty rates were outstanding and the company had an impressive awards track record as best employer in the Netherlands (Exhibit 7). This status has served the company very well in recruiting. In the Dutch IT labor market, a strong brand name in the eyes of future employees was absolutely critical to a firm's later success. For start-ups, the lack of such strong brand equity to future employees was one of the most significant hurdles.

Thanks to Hans van der Kooij's inspirational, and in some ways paternalistic, leadership, employees have identified with the firm to a great extent. Most, if not all, employees shared a common value system and had a very strong sense of belonging to the Caesar Group. However this shared culture among Caesar employees had not led to "groupthinking". In fact, what defined the company culture most was the challenging of commonly held ideas and the eternal "why" question that popped up in any managerial meeting.

The 2001 Bubble

In 2001, Caesar at first thought the crisis was going to be an opportunity for a cost leader rather than a threat. Management expected that Caesar's gain in market share, due to an increase in competitiveness, would more than compensate for the market shrinkage, which was forecasted around minus 5%. Unfortunately the magnitude of the crisis was in reality greater than initially expected, around minus 40%. Even upper end players, such as Logica CMG, lowered prices below costs in order not to lose customers, therefore nullifying Caesar's competitive advantage.

In the years following the crisis, the industry underwent a consolidation process. Many companies went bankrupt or were taken over by other companies. Caesar received several acquisition offers in 2002 as well, but Hans van der Kooij decided not to sell the company despite sales suffering and the layoff of employees. However, management realized that the cost leadership strategy was not sustainable anymore and felt a strategic change was urgent.

Focus on ROI of IT Application Systems

The strategic change toward a "value" strategy at first resulted in a focus on the Return On Investment firms obtained on application software. Caesar decided to organize its fee structure based on the savings the customers would enjoy thanks to the implementation of their application software. However, this proposition was not sustainable for two reasons. First, Caesar underestimated the management attention this strategy needed on the internal side, hurting profitability. Second, they did not have complete control over the customer's processes (such as project management, business need definition, and implementation), leading to a lack of ROI for the customer, through the customer's own doing.

Towards Operational Excellence

The company underwent another radical change in 2003 and extended its "body-shopping" offer to the execution and management of IT software development projects (custom-made software). Between 2003 and 2005, Caesar developed a project methodology - TimeValue -to deliver IT software development projects on time and within budget. This project methodology was embedded in Goldratt's Theory of Constraints method (Exhibit 8 offers a primer on TOC). In fact, Caesar was the first company around the globe that applied the TOC method to a service business. Through TOC, Caesar was able to identify why projects were always late, over budget and often out of scope and to think about viable solutions for these issues. As a research study demonstrated, these matters were relevant concerns. According to a 2004 report published by the Standish Group with data from more than 50,000 projects, 82% of projects deliver late, 53% of the projects exceed their budget (on average, 1.9 times), 71% do not fulfill expectations.

Caesar also identified that there was a critical mismatch between customer and provider. Given that the service provider was paid on an hourly base, there was a strong incentive in delaying the project and delivering late, which generated frustration on the client's side. Caesar came to realize that such a mismatch could be fixed through aligning the goals of customer and provider by choosing a pricing strategy that guaranteed "fixed time and fixed budget type" of agreement with clients, the so called TimeValue projects. In the case of a project delivery being delayed, clients would only pay Caesar half the price. Buffer time management was critical in building Caesar's operational advantage and in implementing state-of-the art TOC method in the IT services (Exhibit 9).

The Struggle to Turn Operational Excellence into Sales and Profits

In 2005, Caesar proceeded with the market launch of its TimeValue project proposition, expecting it to take off immediately. However, by the end of 2006, the results were disappointing and sales did not reach these sky-high expectations. Sales of TimeValue projects did not pick up, nor did profits, and Caesar started losing sales in body-shopping because of the excessive focus on TimeValue projects. The origin of the launch failure lay mainly in three interconnected problems.

A first problem was the brand association customers made with the name Caesar and the change in value proposition that the company aimed to deliver to its clients. Caesar sold one clearly differentiated product with high methodological excellence (TimeValue projects) and one commodity product without a unique selling proposition (IT body shopping) under the same brand name. While Caesar was able to raise interest with potential customers in TimeValue workshops (Exhibit 10), they were not able to make customers comfortable to the extent that initial interest could be converted into a sale. Hans Nijholt, Managing Director of the Projects Division, recalled: "We had problems in getting enough contracts and penetrating the market. (...). We clearly saw a lot of new prospects in our sales but we were still not able to find the way to convert the interest for our proposition into sales."

Connected to the brand confusion, a second problem was the sales process that Caesar employed. The sales process for body-shopping was a short "push" process (average length 2-4 weeks), while the sales process for projects was a long "pull" cycle (average length between 3 and 6 months). The body-shopping sales process often started with a clear customer request for a specific IT capability and capacity, while TimeValue projects often started with raising the interest of the potential client through referencing among customers and TimeValue workshops. While the different steps in the sales process of TimeValue projects (Exhibit 11) were configured in detail by the Sales manager, Luc Spaas, Caesar approached clients in an integrated fashion. Therefore each Sales Representative had both products in the selling portfolio. To make matters worse, sales representatives for the body-shopping proposition seemed to use the appeal of the TimeValue method to get a foot in the door with potential customers to consequently make body-shopping deals. According to Lars de Laat, Value Manager for TimeValue projects: "Many of our sales people still had difficulties in understanding the TimeValue projects and in selling them. People working on hours just work differently from people working to an end date. (...)." Landing body-shopping deals also required completely different sales capabilities than landing TimeValue project deals. The mentality shift from a focus on "number of hours sold" versus "delivery on time and within budget" required alignment in people's attitudes and in performance measures that hadn't been dealt with before by Caesar. Hans Nijholt recalled: "Selling body-shopping hours is completely different from selling an LT project. We definitely underestimated the different skills and the type of behavior needed to conduct this type of sale: selling a house is more difficult than selling a carpet. Furthermore we didn't change the measures by which we would assess the performance of the sales force... and, people behave in the way you measure them."

A third problem was frustration in the service delivery process. The situation progressively led to internal struggles and tension among talented employees. Management couldn't help feeling that people working on TimeValue projects were in a different (higher) league than those working on the body-shopping business. In Hans van der Kooij's words it seemed as if "TimeValue projects were the ideal division to work for in Caesar." Internally, operations were repeatedly frustrated by the lack of focus on either body-shopping or TimeValue projects. Furthermore the Human Resource people managing the talent pool were always confronted with the dilemma on whether to "sell" the best people "as bodies" or to keep them free for a potential upcoming TimeValue project, taking the very likely risk of keeping the best talents idle for many months. Here is management's take, in Lars de Laat's words, on the internal situation as of 2007: "We were two years down the road, and we were still not successful! Not only did we not succeed in growing the business, but also people in the company were fighting each other as if they had different goals. Many managers were feeling uncomfortable; they felt they had a foot in each camp, as if they had to choose between the two and they didn't know how to pick".

Research Plan

Facing this struggle, Marjon Vermeulen, Caesar's VP of Marketing, spearheaded a taskforce to understand and address the first two marketing problems described above. She decided to analyze customer behavior in more detail to clarify customers' needs and to identify a way to address them. With the help of the Marketing Technology and Innovation Institute (www.mti2.eu), an external marketing consultant, Caesar ran the following customer research.

First, Caesar conducted qualitative interviews with customers. The finding was that Caesar could really differentiate itself on its TimeValue projects business. Marjon Vermeulen recalled: "Some customers were totally impressed by our performance in TimeValue projects and described them as "Too good to be true" and "You'll only believe it when you see it"." For its body-shopping business, at first qualitative research did not hint at any differentiator in Caesar's offering.

Consequently, the firm decided to quantitatively test the proposition "a deal is a deal" for TimeValue projects and its attributes in a conjoint analysis (Exhibit 12offers a primer on conjoint analysis). Such conjoint analysis allowed Caesar to discern the price point which it could target and the size of the potential target market. The conjoint analysis (see Exhibit 13 for the raw partworths across customer segments) led to the following conclusions: 1) the three most important attributes were price, time and budget guarantee, and the brand name in that order, while delivery speed and methodology were found not to be crucial; 2) customers could be clustered in three main segments: Segment 1 (59% of the market) valued the brand name of a supplier and was less price-sensitive (even associating less utility to a low priced supplier than to a medium priced supplier)2; Segment 2 (25% of the market) valued a time and budget guarantee very highly and was moderately price sensitive; Segment 3 (16% of the market) was very price sensitive. A large scale survey further supported the relative sizes of the above target segments. In addition, from a correlation of the segments that were derived from the conjoint analysis for projects, Caesar learnt that IT managers in the guarantee segment were frustrated by projects running over time to a greater extent than IT managers in other segments and they were in general also more entrepreneurial. According to Marjon Vermeulen: "The conjoint study represented a major turning point for marketing projects. We understood we had a specific customer segment to target: the so-called "entrepreneurial" IT Manager. This segment was strongly interested in the Project value proposition and represented a quarter of the potential customer base."

Convinced by the power of conjoint analysis, Caesar moved on to conceptualize potential differentiators for the body-shopping business. Through internal brainstorming sessions, a lead user customer group and qualitative interviews with IT managers, the company derived five potential sources of differentiation:

Whether the supplier focused on specific applications or rather served as an integrator across applications.

Whether the supplier promptly delivered resumes of IT professionals.

Whether the supplier knew the organizational routines of the firm, for instance through prior experience with that firm or with other firms in the same industry.

Whether the supplier offered a "no questions asked" satisfaction guarantee.

Whether the supplier had loyalty programs rewarding long customer relationships.

In an exploration phase, Caesar decided to test whether any of the key differentiators above could match with limited price sensitivity of customers. The results of the conjoint are reported inExhibit 14. The main conclusions were: (1) A strong satisfaction guarantee was the strongest differentiator, followed by prior knowledge of organizational processes; (2) four main segments existed: Segment 1 (15% of the market) cared very much about prior knowledge of organizational processes; Segment 2 (8% of the market) was very price sensitive; Segment 3 (25% of the market) cared about the satisfaction guarantee; Segment 4 (52% of the market) was not very specific about what it looked for exactly. The latter segment confirmed that the market for body-shopping was pretty much a commodity market. On the basis of this conjoint study, Caesar started an implementation process for a full service satisfaction guarantee on its body-shopping contracts and decided also to initiate a relationship management program.

Issues to be Resolved

After gaining the above customer inputs, Marjon Vermeulen brought together the main decision-makers in the firm to resolve the issues Caesar was facing. The critical matters she put on the agenda were the following:

What are the core learnings from the customer research that Caesar has conducted?

Can the two (TimeValue projects versus body-shopping) value propositions be successful in the same firm? Why? Why not?

Is there some better structure for Caesar that would serve the overall firm goals, but also make the two units improve further both in profits and sales?

How should the brand be positioned? Can the same brand be used to market the different value propositions?

1) Establish Problem

2) Establish Recommendations

3) Create decision matrix

3) Provide Finacials/Analyis

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started