can i get some helo with the questions at the end of the case??

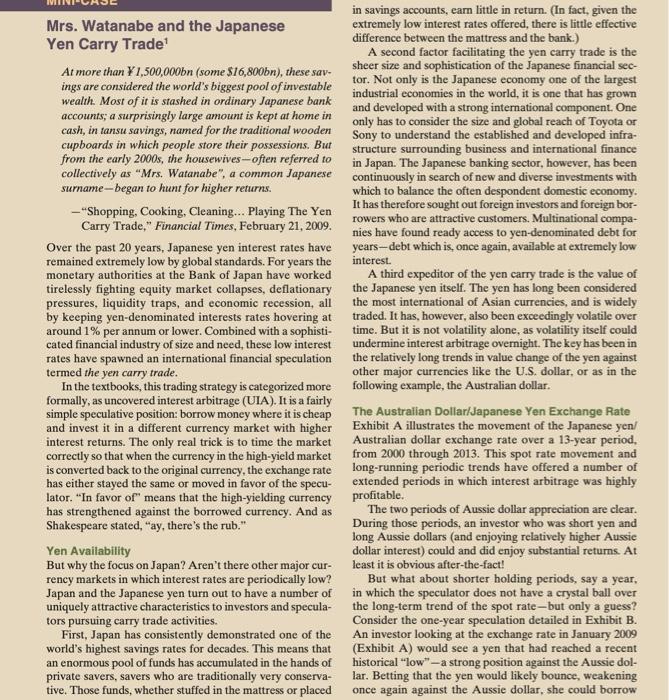

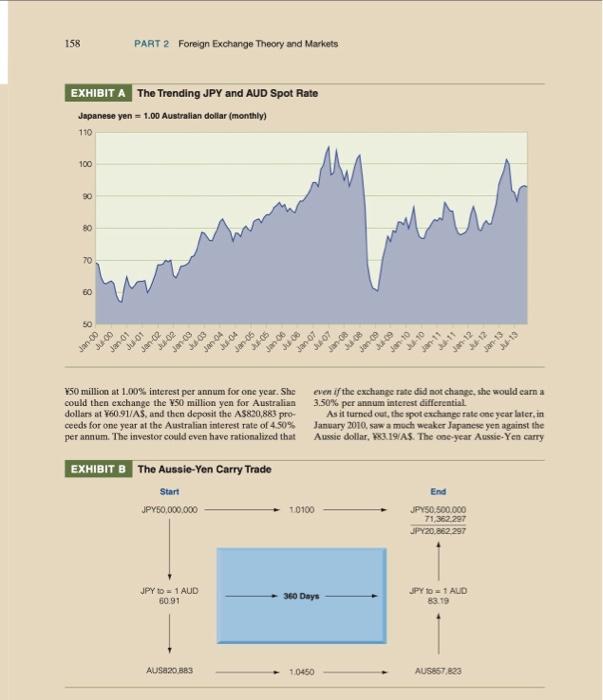

\$50 million at 1.00% interest per annum for one year. She could then exchange the Y50 million yen for Australian dollars at $60.91/AS, and then deposit the A $820,883 proceeds for one year at the Australian interest rate of 4.50% per annum. The investor could even have rationalized that even if the exchange rate did not change, whe would earn a 3.50% per annum interest differential. As it turned cut, the spot exchange rate one year later, in January 2010 saw a moch weaker Japanese yen against the Aussie dollar, K83.19/AS. The one-year Aussie-Yea carry Mrs. Watanabe and the Japanese Yen Carry Trade 1 At more than 1,500,000bn (some $16,800bn ), these savings are considered the world's biggest pool of investable wealth. Most of it is stashed in ordinary Japanese bank accounts; a surprisingly large amount is kept at home in cash, in tansu savings, named for the traditional wooden cupboards in which people store their possessions. But from the early 2000 s, the housewives-often referred to collectively as "Mrs. Watanabe", a common Japanese surname-began to hunt for higher returns. - "Shopping, Cooking, Cleaning... Playing The Yen Carry Trade," Financial Times, February 21, 2009. Over the past 20 years, Japanese yen interest rates have remained extremely low by global standards. For years the monetary authorities at the Bank of Japan have worked tirelessly fighting equity market collapses, deflationary pressures, liquidity traps, and economic recession, all by keeping yen-denominated interests rates hovering at around 1% per annum or lower. Combined with a sophisticated financial industry of size and need, these low interest rates have spawned an international financial speculation termed the yen carry trade. In the textbooks, this trading strategy is categorized more formally, as uncovered interest arbitrage (UIA). It is a fairly simple speculative position: borrow money where it is cheap and invest it in a different currency market with higher interest returns. The only real trick is to time the market correctly so that when the currency in the high-yield market is converted back to the original currency, the exchange rate has either stayed the same or moved in favor of the speculator. "In favor of" means that the high-yielding currency has strengthened against the borrowed currency. And as Shakespeare stated, "ay, there's the rub." Yen Availability But why the focus on Japan? Aren't there other major currency markets in which interest rates are periodically low? Japan and the Japanese yen turn out to have a number of uniquely attractive characteristics to investors and speculators pursuing carry trade activities. First, Japan has consistently demonstrated one of the world's highest savings rates for decades. This means that an enormous pool of funds has accumulated in the hands of private savers, savers who are traditionally very conservative. Those funds, whether stuffed in the mattress or placed in savings accounts, earn little in return. (In fact, given the extremely low interest rates offered, there is little effective difference between the mattress and the bank.) A second factor facilitating the yen carry trade is the sheer size and sophistication of the Japanese financial sector. Not only is the Japanese economy one of the largest industrial economies in the world, it is one that has grown and developed with a strong international component. One only has to consider the size and global reach of Toyota or Sony to understand the established and developed infrastructure surrounding business and international finance in Japan. The Japanese banking sector, however, has been continuously in search of new and diverse investments with which to balance the often despondent domestic economy. It has therefore sought out foreign investors and foreign borrowers who are attractive customers. Multinational companies have found ready access to yen-denominated debt for years-debt which is, once again, available at extremely low interest. A third expeditor of the yen carry trade is the value of the Japanese yen itself. The yen has long been considered the most international of Asian currencies, and is widely traded. It has, however, also been exceedingly volatile over time. But it is not volatility alone, as volatility itself could undermine interest arbitrage overnight. The key has been in the relatively long trends in value change of the yen against other major currencies like the U.S. dollar, or as in the following example, the Australian dollar. The Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen Exchange Rate Exhibit A illustrates the movement of the Japanese yen/ Australian dollar exchange rate over a 13-year period, from 2000 through 2013. This spot rate movement and long-running periodic trends have offered a number of extended periods in which interest arbitrage was highly profitable. The two periods of Aussie dollar appreciation are clear. During those periods, an investor who was short yen and long Aussie dollars (and enjoying relatively higher Aussie dollar interest) could and did enjoy substantial returns. At least it is obvious after-the-fact! But what about shorter holding periods, say a year, in which the speculator does not have a crystal ball over the long-term trend of the spot rate-but only a guess? Consider the one-year speculation detailed in Exhibit B. An investor looking at the exchange rate in January 2009 (Exhibit A) would see a yen that had reached a recent historical "low" - a strong position against the Aussie dollar. Betting that the yen would likely bounce, weakening once again against the Aussie dollar, she could borrow trade position would then have earned a very healthy profit of 20,862,296.83 on a one-year investment of 50,000,000, a 41.7% rate of return. Post 2009 Financial Crisis The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 has left a marketplace in which the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have pursued easy money policies. Both central banks, in an effort to maintain high levels of liquidity and to support fragile commercial banking systems, have kept interest rates at near-zero levels. Now global investors who see opportunities for profit in an anemic global economy are using those same low-cost funds in the U.S. and Europe to fund uncovered interest arbitrage activities. But what is making this "emerging market carry trade" so unique is not the interest rates, but the fact that investors are shorting two of the world's core currencies: the dollar and the euro. Consider the strategy outlined in Exhibit B. An investor borrows EUR 20 million at an incredibly low rate, say 1.00% per annum or 0.50% for 180 days. The EUR 20 million are then exchanged for Indian rupees (INR), the current spot rate being INR 60.4672= EUR 1.00. The resulting INR 1,209,344,000 are put into an interest-bearing deposit with any of a number of Indian banks attempting to attract capital. The rate of interest offered, 2.50%, is not particularly high, but is greater than that available in the dollar, euro, or even yen markets. But the critical component of the strategy is not to earn the higher rupee interest (although that does help), it is the expectations of the investor regarding the direction of the INR per EUR exchange rate. CASE QUESTIONS 1. Why are interest rates so low in the traditional core markets of USD and EUR? 2. What makes this "emerging market carry trade" so different from traditional forms of uncovered interest arbitrage? 3. Why are many investors shorting the dollar and the euro