Can you think of other organizations that resemble Digital Equipment Corporation?

What is similar and what is different,and why?

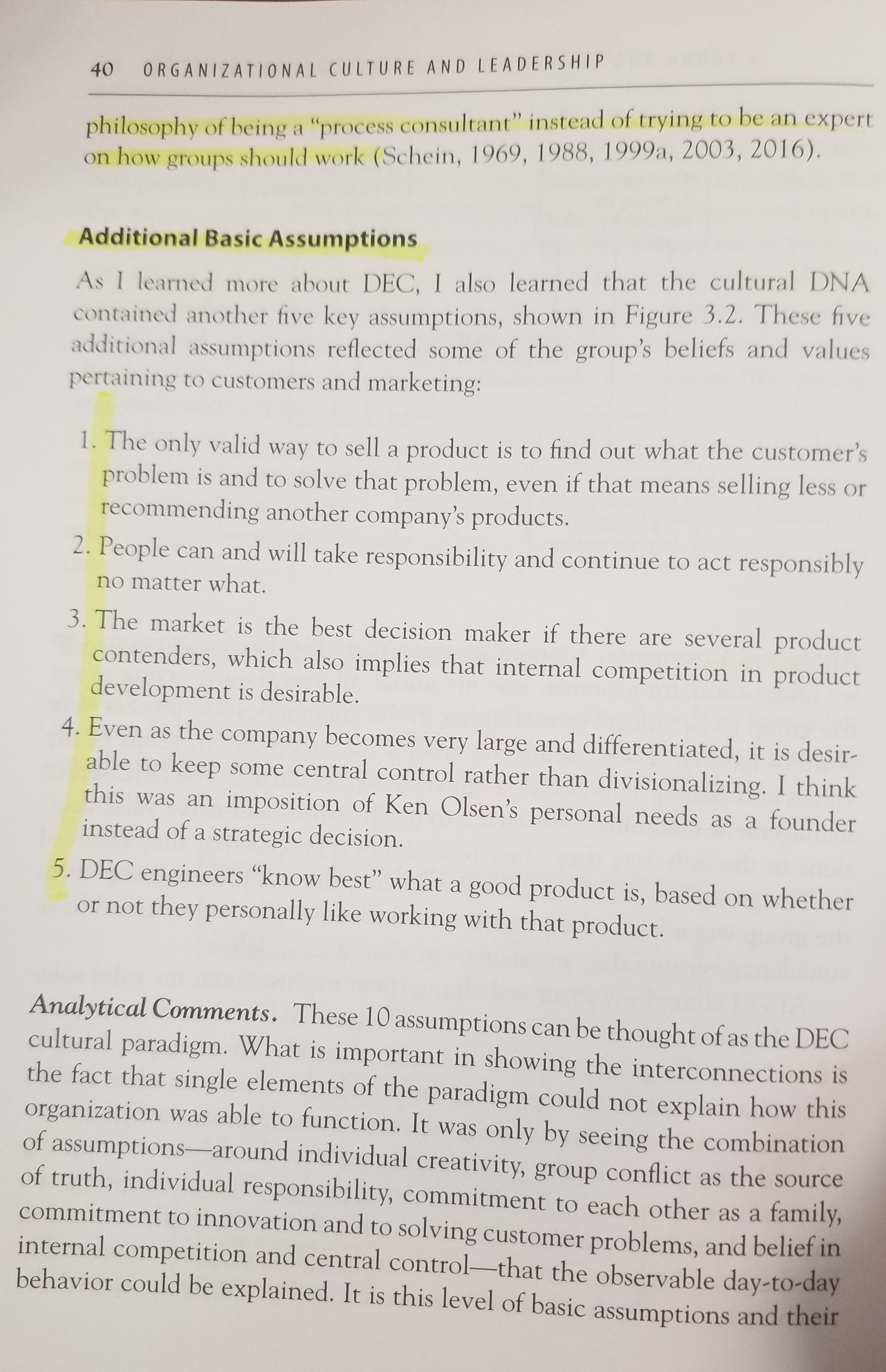

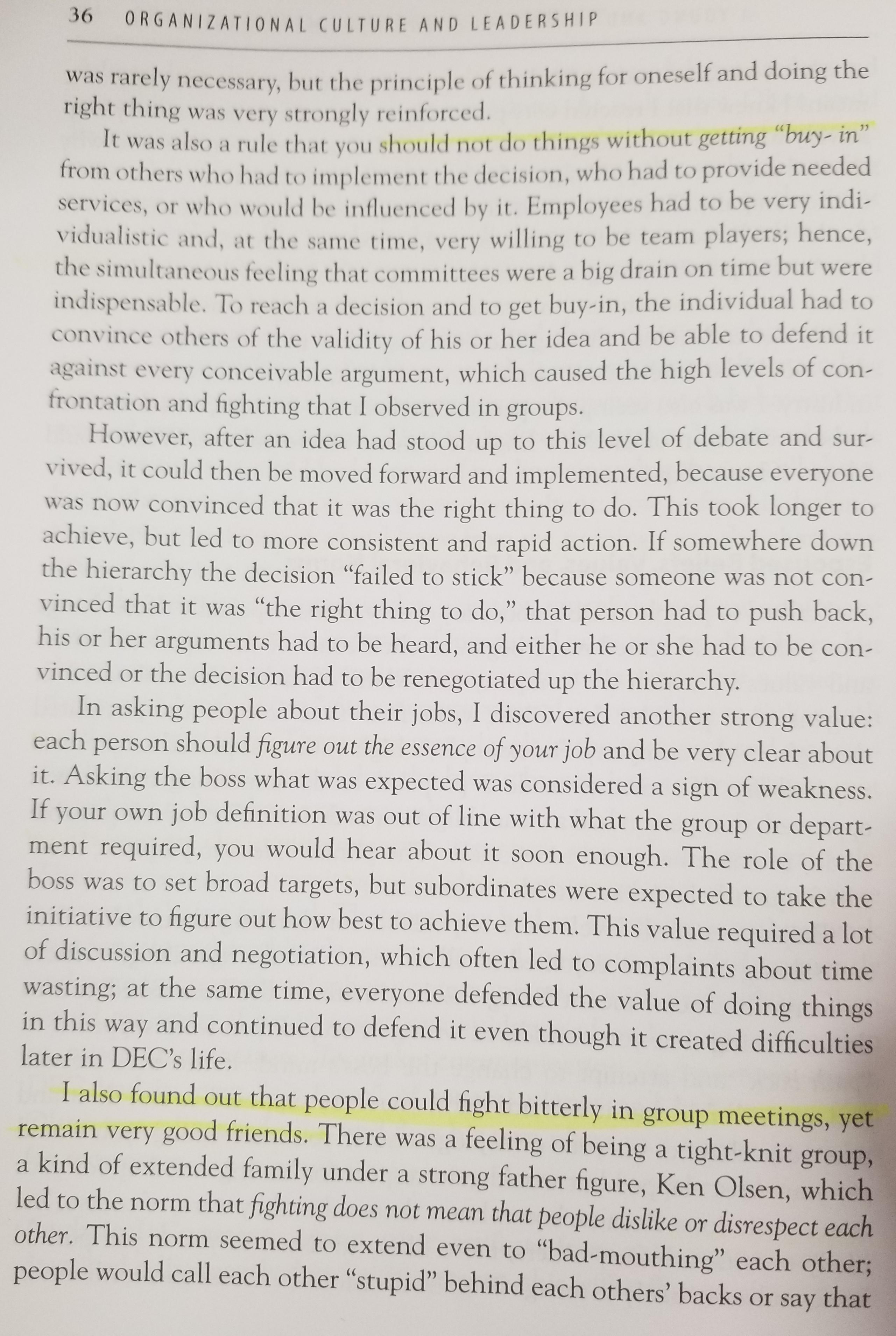

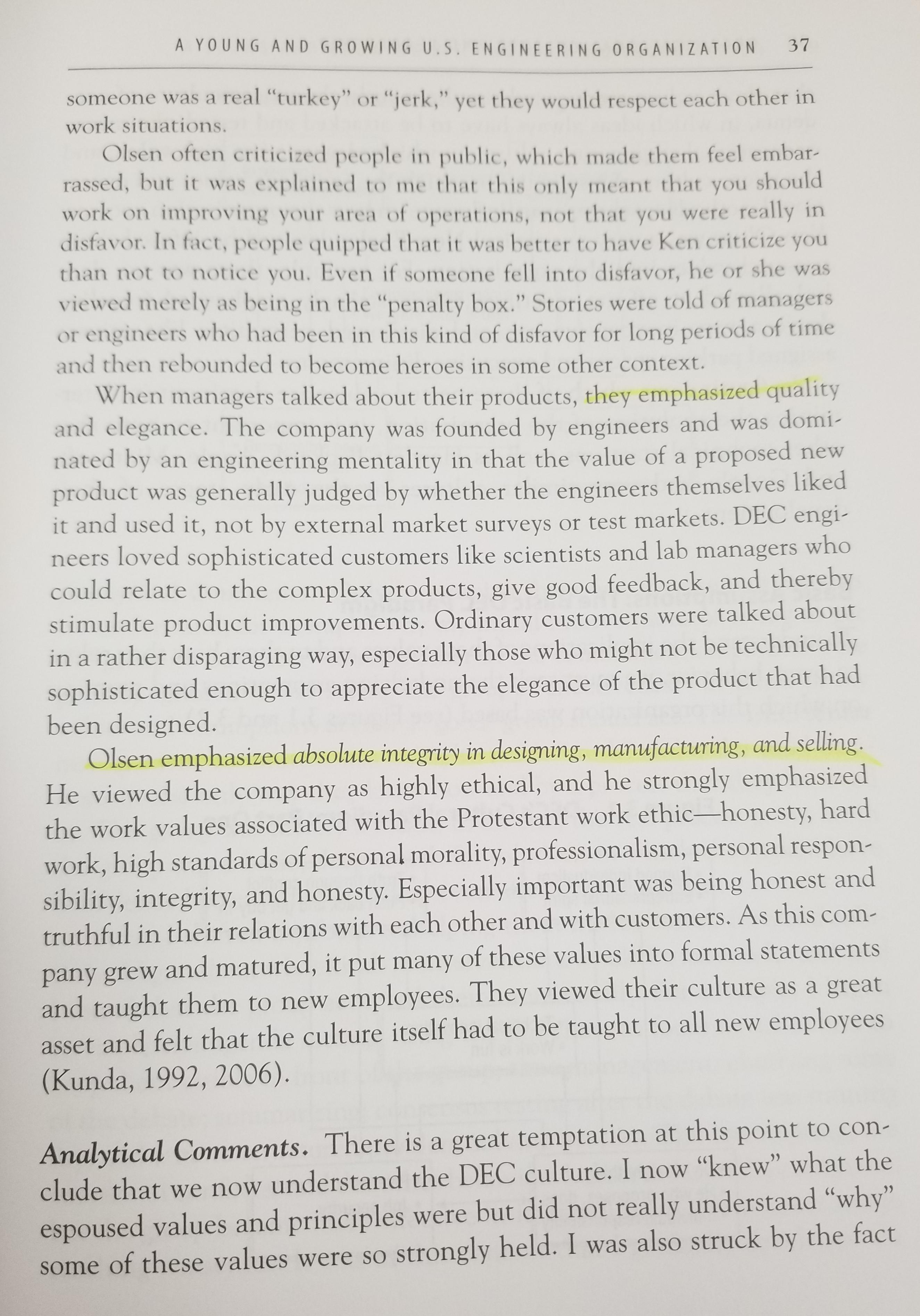

W A YOUNG AND GROWING U.S. ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION How culture works and how to analyze and assess cultural phenomena is best illustrated through cases that represent different stages of organiza- tional evolution. In this chapter I review the case of an organization that I was fortunate enough to encounter in its youth and able to follow through its entire life cycle. At one level this is an "old" case from the 1960s, but the culture dynamics I encountered then continue to be visible in compa- nies that I observed in recent years and seem to characterize technically based start-ups. Case 1: Digital Equipment Corporation in Maynard, Massachusetts Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was the first major company to introduce interactive computing in the mid-1950s, and it became a very successful manufacturer of what came to be called "mini computers." It was located primarily in the northeastern part of the United States, with headquarters in an old mill in Maynard, Massachusetts, but it had branches throughout the world. At its peak, it employed more than 100,000 people, with sales of $14 billion. In the mid-1980s it became the second largest computer manufacturer in the world after IBM. The company ran into major financial difficulties in the 1990s and was eventually sold to the Compaq Corp. in 1998. Compaq was in turn acquired by Hewlett-packard in 2001. There were innumerable stories written about why and how DEC "failed," but few of them provided a cultural perspective on either its rise or its failure. I was involved with DEC as a consultant from 1966 to 1992, and therefore was privy to much of the inside story of how this40 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP philosophy of being a "process consultant" instead of trying to be an expert on how groups should work (Schein, 1969, 1988, 1999a, 2003, 2016). Additional Basic Assumptions As I learned more about DEC, I also learned that the cultural DNA contained another five key assumptions, shown in Figure 3.2. These five additional assumptions reflected some of the group's beliefs and values pertaining to customers and marketing: 1. The only valid way to sell a product is to find out what the customer's problem is and to solve that problem, even if that means selling less or recommending another company's products. 2. People can and will take responsibility and continue to act responsibly no matter what. 3. The market is the best decision maker if there are several product contenders, which also implies that internal competition in product development is desirable. 4. Even as the company becomes very large and differentiated, it is desir- able to keep some central control rather than divisionalizing. I think this was an imposition of Ken Olsen's personal needs as a founder instead of a strategic decision. 5. DEC engineers "know best" what a good product is, based on whether or not they personally like working with that product. Analytical Comments. These 10 assumptions can be thought of as the DEC cultural paradigm. What is important in showing the interconnections is the fact that single elements of the paradigm could not explain how this organization was able to function. It was only by seeing the combination of assumptions-around individual creativity, group conflict as the source of truth, individual responsibility, commitment to each other as a family, commitment to innovation and to solving customer problems, and belief in internal competition and central control-that the observable day-to-day behavior could be explained. It is this level of basic assumptions and theirA YOUNG AND GROWING U.S. ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION 41 interconnections that defines some of the essence of the culture-the key genes of the cultural DNA at this stage of DEC's development. This paradigm is a mixed combination of U.S. macro-cultural values of individualism, competition, and pragmatism and family values such as loy- alty, frugality, truth, and commitment to customers as represented by Ken Olsen and the engineers he hired. It illustrates the enormous power of the founder of an organization in how he infuses it with the values and assump- tions he brings with him from his own cultural background. How general was this paradigm in DEC? That is, if we were to study various micro systems such as the workers in the plants, salesmen in geo- graphically remote units, engineers in technical enclaves, and so on, would we find the same assumptions operating? One of the interesting aspects of the DEC story is that at least for its first 20 or so years, this paradigm would have been observed in operation across most of its rank levels, func- tions, and geographies. Much of it was explicitly taught to all newcomers through periodic "boot camps," and much of it was written down as the DEC culture. Some of these assumptions were modified in functions such as sales and service where the pragmatic needs to relate well to customers created new and different subcultural elements-hierarchy, status rituals, more rapid decision making, and more discipline. As we will see subse- quently, as DEC grew, aged, and evolved, some basic elements of the DEC culture began to change, whereas other elements that did not change, even as they became dysfunctional in the changing market environment, led ultimately to DEC's decline. Because of my continuing contact with this company I was able to con- struct the detailed picture of the organization that is presented in the figures. This level of detail was needed to understand some of the puzzling behavior I had observed and to describe the organization to outside observers. But it must be noted that much of the current emphasis in culture research focuses on how one might change culture to improve performance. To change culture requires the insider change leaders to understand their cul- ture at a detailed level and especially to identify various stable elements that were the source of the company's success, but it is not important for the researcher or outside observer to understand the culture in as much detail as I was able to gather. The consultant, the future employee, the investor, the supplier, or the customer needs to know some elements of an42 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP organization's culture, but he or she does not need to invest in the kind of clinical study that I was able to do in this case. Summary and Conclusions The crucial insight to take away from this case is that a young company's culture provides identity, meaning, and daily motivation. If the company is successful, that culture will become very strong and explicitly part of its identity. We see today articles and books by many organizations explicitly touting their culture and suggesting that it is the culture that is making those organizations successful. The DEC story should remind us that we cannot really make generalizations about culture without specifying the age, size, and underlying technology of the company, because each of those factors played a role in what the DEC culture became. We also have to consider in what way the given company culture is nested in various occur pational and national macro cultures. A second important lesson is that the presence of the founder or entre- preneur is a strong stabilizing force for the culture. The implication is that we cannot make generalizations about culture without specifying whether we are talking about a first- or a second-generation company still run by the founder or about a company run by general managers who have been appointed by boards and have worked their way up the managerial ladder. The stability of DEC's commitment to innovation even in the face of mar- kets that wanted simpler turnkey products could be explained in part by the presence of the founder, whose deep assumptions and beliefs were difficult to challenge. In the following chapter we will look at an entirely different kind of organization at a different stage of development and in a different industry.32 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP company grew, peaked, and declined (Schein, 2003). I was a consultant to the founder, Ken Olsen, and to the various executives over this entire period, which provided a unique opportunity to see cultural dynamics in action over most of the life of this company. DEC's history is a prime example of how the deeper cultural layers, the basic assumptions, explain both the rise and fall of the company and will be used throughout this book as a major case example that illustrates macro and micro culture interactions. In this chapter we begin by analyzing the company's culture structurally, using the framework provided in Chapter 2. In later chapters I will refer to various cultural forces that illuminate DEC as a start-up, DEC as a mid-life company, and DEC in decline. Start-ups and old companies have received a lot of attention in the organizational literature, but there are not many studies of an entire life cycle of a single company under its founder. Such studies become especially important as organization theory puts increasing attention on agility and "ambidexterity" as a key property of organizations that have survived for a long time (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2016). What these authors show with the use of this concept is that long-range survival seems to hinge on the ability to manage both the existing business, which has been the reason for success thus far, and at the same time to develop a new business that is more responsive to changing environmental conditions. If the organization cannot do that for itself, it will inevitably attract competitors who will "disrupt" the present business by creating new businesses that are more adaptive and will, therefore, eventually put the old business into decline (Christensen, 1997). So with this theoretical back- ground, let's meet DEC. Artifacts: Encountering the Company To gain entry into any of DEC's many buildings, you had to sign in with a guard who sat behind a counter where there were usually several people chatting, moving in and out, checking the badges of employees who were coming into the building, accepting mail, and answering phone calls. After signing in, you waited in a small, casually furnished lobby until the person you were visiting came personally or sent a secretary to escort you into the work areas.N; . ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION 33 What I recall most vividl tion was the ubiquitous ope of dress and manne y from my first encounters with this organiza' nuiiice architecture, the extreme informality . rs, a very dynamic environment in the sense of rapid pace, and t1 lilgh rate 0f interaction among employees, seemingly reeCt' mg enthustasm, intensity, energy, and impatience. As I would pass cubicles f. i rooms, I would get the impression of openness. There were \\ to my t oors, and I learned later that Ken Olsen, the founder, had for, lwildden doors on engineers' ofces. The company cafeteria spread out into a 1g open area where people sat at large tables, hopped from one table to another, and ObVIOusly were intensely involved 1 I also observed that there were many cubicles with coffee machines and refrigerators in them and that food seemed to be part of most meetings. For morning meetings one or another member brought boxes of fresh donuts for all to enjoy. or conference The physical layout and patterns of interaction made it very dif cult to decipher who had what rank, and I was told that there were no status perquisites such as private dining rooms, special parking places, or ofces with special Views and the like. The furniture in the lobbies and ofces was very inexpensive and functional. The company was mostly headquartered in an Old industrial building. The informal clothing worn by most managers and employees reinforced this sense of economy and egalitarianism. I had been brought into DEC by Ken Olsen \"to help the top manage; ment team improve communication and group effectiveness.\" As I began to attend the regular staff meetings of the senior management group, I was quite struck by the high level of interpersonal confrontation, argumentar tiveness, and conict. Group members became highly emotional at the drop of a hat, interrupted each other constantly, and seemed to become angry at each other, though it was also noticeable that such anger did not carry over outside the meeting. With the exception of the president and founder, Ken Olsen, there were very few people who had Visible status in terms of how people deferred to them. Olsen himself, through his informal behavior, implied that he did I take his position of power all that seriously: Group members argued as i\" th him as with each other and even interrupted him from time status did show up, however, in the occasional lectures he 3 4 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP V delivered to the group when he felt that members did not understand something or were "wrong" about something. At such times, Olsen could become very emotionally excited in n way tlmt other members of the grup never did. 1 learned l'mm further ohservnlion that this style of running meetings \"\"5 Wl'icnl and that meetings were very common. to the pomt Where People would complain about all the time spent in committees At the same time. they Would argue that without these committees they could not get their work done properly. My mm reactions to the company and these meetings also must be considered as artifacts to be documented. It was exciting to be attending top management meetings and surprising to observe so much behavior that seemed to me dysfunctional. The level of confrontation I observed made me quite nervous, and I had a sense of not knowing what this was all about, but it also provided me an agenda as a consultant: how to x this dysfunCr tional group in terms of what I knew from my training were the character; istics of effective groups. The company was organized as a matrix, one of the earliest versions of this type of organization in terms of functional units and product lines, but there was a sense of perpetual reorganization and a search for a structure that would \"work better.\" Structure was viewed as something to tinker with until you got it right. There were many levels in the technical and manage rial hierarchy, but I sensed that the hierarchy was just a convenience, not something to be taken very seriously. However, the communication structure was taken very seriously. There were many committees already in existence, and new ones were constantly being formed. The company had an extensive email networ that functioned worldwide; engineers and managers traveled frequen and were in constant telephone communication with each other. Oi, ' would get upset if he observed any evidence of under'communio or miscommunication. To make communication and contact l DEC had its own \"air force\" of several planes and helicopte , Olsen was a licensed pilot and ew his own plane to a retreat in ' for recreation. Analytical Comment. Many other artifacts from this organ described subsequently; but for the present, this will sufce to gi- A YOUNG AND GROWING U . S . ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION 35 of what I encountered at DEC. The question now is, what does any of it mean? I knew that I reacted very positively to the informality but very neg- atively to the unruly group behavior, but I did not really understand why these things were happening and what significance they had for members of the company. To gain some understanding, I had to get to the next level: the level of espoused beliefs, values, and behavioral norms. At this point I thought I was observing subcultures ( the various work areas) and micro cultures ( the various group meetings) that reflected pri- marily the technology driving the business-that is, inventing computers that would be interactive, could sit on a desk, and could create a new industry. I was also seeing the personal style of the founder, which seemed to be a reflection of the New England Yankee macro culture. What would I learn if I asked questions? Espoused Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms As I talked to people at DEC about my observations, especially those things that puzzled and scared me, I began to elicit some of the espoused beliefs and values by which the company ran. Many of these were embodied in slogans or in parables that Olsen wrote from time to time and circulated throughout the company. For example, a high value was placed on personal responsibility. If someone made a proposal to do something and it was approved, that person had a clear obligation to do it or, if it was not possible to do, to come back and renegotiate. The phrase "He who proposes, does" was frequently heard around the organization. Employees at all levels were responsible for thinking about what they were doing and were enjoined at all times to "do the right thing," which, in many instances, meant being insubordinate. If the boss asked you to do something that you considered wrong or stupid, you were supposed to "push back" and attempt to change the boss's mind. If the boss insisted and you still felt that it was not right, you were supposed to not do it and take your chances on your own judgment. If you were wrong, you would get your wrist slapped but would gain respect for having stood up for your own convictions. Because bosses knew these rules, they were, of course, less likely to issue arbitrary orders, more likely to listen to you if you pushed back, and more likely to renegotiate the decision. So actual insubordination36 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP was rarely necessary, but the principle of thinking for oneself and doing the right thing was very strongly reinforced. It was also a rule that you should not do things without getting "buy- in" from others who had to implement the decision, who had to provide needed services, or who would be influenced by it. Employees had to be very indi- vidualistic and, at the same time, very willing to be team players; hence, the simultaneous feeling that committees were a big drain on time but were indispensable. To reach a decision and to get buy-in, the individual had to convince others of the validity of his or her idea and be able to defend it against every conceivable argument, which caused the high levels of con- frontation and fighting that I observed in groups. However, after an idea had stood up to this level of debate and sur- vived, it could then be moved forward and implemented, because everyone was now convinced that it was the right thing to do. This took longer to achieve, but led to more consistent and rapid action. If somewhere down the hierarchy the decision "failed to stick" because someone was not con- vinced that it was "the right thing to do," that person had to push back, his or her arguments had to be heard, and either he or she had to be con- vinced or the decision had to be renegotiated up the hierarchy. In asking people about their jobs, I discovered another strong value: each person should figure out the essence of your job and be very clear about it. Asking the boss what was expected was considered a sign of weakness. If your own job definition was out of line with what the group or depart- ment required, you would hear about it soon enough. The role of the boss was to set broad targets, but subordinates were expected to take the initiative to figure out how best to achieve them. This value required a lot of discussion and negotiation, which often led to complaints about time wasting; at the same time, everyone defended the value of doing things in this way and continued to defend it even though it created difficulties later in DEC's life. I also found out that people could fight bitterly in group meetings, yet remain very good friends. There was a feeling of being a tight-knit group, a kind of extended family under a strong father figure, Ken Olsen, which led to the norm that fighting does not mean that people dislike or disrespect each other. This norm seemed to extend even to "bad-mouthing" each other; people would call each other "stupid" behind each others' backs or say thatA YOUNG AND GROWING U. S . ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION 37 someone was a real "turkey" or "jerk," yet they would respect each other in work situations. Olsen often criticized people in public, which made them feel embar- rassed, but it was explained to me that this only meant that you should work on improving your area of operations, not that you were really in disfavor. In fact, people quipped that it was better to have Ken criticize you than not to notice you. Even if someone fell into disfavor, he or she was viewed merely as being in the "penalty box." Stories were told of managers or engineers who had been in this kind of disfavor for long periods of time and then rebounded to become heroes in some other context. When managers talked about their products, they emphasized quality and elegance. The company was founded by engineers and was domi- nated by an engineering mentality in that the value of a proposed new product was generally judged by whether the engineers themselves liked it and used it, not by external market surveys or test markets. DEC engi- neers loved sophisticated customers like scientists and lab managers who could relate to the complex products, give good feedback, and thereby stimulate product improvements. Ordinary customers were talked about in a rather disparaging way, especially those who might not be technically sophisticated enough to appreciate the elegance of the product that had been designed. Olsen emphasized absolute integrity in designing, manufacturing, and selling. He viewed the company as highly ethical, and he strongly emphasized the work values associated with the Protestant work ethic-honesty, hard work, high standards of personal morality, professionalism, personal respon sibility, integrity, and honesty. Especially important was being honest and truthful in their relations with each other and with customers. As this com- pany grew and matured, it put many of these values into formal statements and taught them to new employees. They viewed their culture as a great asset and felt that the culture itself had to be taught to all new employees (Kunda, 1992, 2006). Analytical Comments. There is a great temptation at this point to con- clude that we now understand the DEC culture. I now "knew" what the espoused values and principles were but did not really understand "why" some of these values were so strongly held. I was also struck by the fact38 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP that those values represented simultaneously the macro culture of aca- demia, in which ideas always have to be attacked and tested; the macro occupational engineering culture, in which elegance is a high value; and the micro culture of a start-up, in which the founder's values and opera- tional methods are the primary influence on how the organization evolves. Ken Olsen was a very puritanical New Englander, and he infused those personal values into the organization. For example, there was no alco- hol allowed at off-site meetings. Olsen strongly emphasized frugality, drove a very inexpensive car, and disallowed perquisites like private assigned parking spaces and executive dining rooms. In figuring out which of these nested values are dominant in deter- mining the evolution of the organization, it is important to note that other technical start-ups such as Hewlett-packard, Apple, Microsoft, and Google had very similar cultures at the early stages of their development. Basic Assumptions: The Basic DEC Paradigm To understand the implications of these values and to show how they relate to overt behavior, we must seek the underlying assumptions and premises on which this organization was based (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2). Figure 3.1 DEC's Cultural Paradigm: Part One . Rugged individualism . Truth through conflict . Entrepreneurial spirit . Push back and get buy-in . Technical innovation . Work is fun Do the right thing . He who proposes, does . Paternalistic family . Job security . Individual responsibilityA YOUNG AND GROWING U. S . ENGINEERING ORGANIZATION 39 Figure 3.2 DEC's Cultural Paradigm: Part Two . Moral commitment to solving the . Internal competition customer's problem . Let the market decide Engineering arrogance . We know what is best . Idealism . Responsible people . Keep central control of goodwill can solve the problem Analytical Comments. Only by grasping these first five assumptions can we understand, for example, why my initial interventions of trying to get the group to be "nicer" to each other in the communication process were politely ignored. I was seeing the group's "effectiveness" in terms of my values and assumptions of how a "good" group should act. The DEC senior management committee was trying to reach "truth" and make valid deci- sions in the only way they knew how and by a process that they believed in. The group was merely a means to an end; the real process going on in the group was a basic, deep search for solutions in which they could have confidence because they stood up even after intense debate. After I shifted my focus to helping them in this search for valid solu- tions, I figured out what kinds of interventions would be more relevant, and I found that the group accepted them more readily. For example, I began to emphasize agenda setting, using the flip-chart to focus on ideas and to keep them visible in front of the group; time management; clarifying some of the debate; summarizing; consensus testing after the debate was running dry; and a more structured problem-solving process. The interrupting, the emotional conflicts, and the other behaviors I observed initially continued, but the group became more effective in its handling of information and in reaching consensus. It was in this context that I gradually developed the