CHAPTER 8:ENTREPRENEURIAL STRATEGY AND COMPETITIVE DYNAMICS CASE STUDY Cirque du Soleil

Instructions: Answer the following questions concerning case studyCirque du Soleilfrom the textbook. There is not a word minimum. Grading will be made in context with text material.

1. How has leadership been able to make a new market space in a traditional industry? Is setting a direction, designing the organization, nurturing a culture sufficient to make a sustainable business?

2. Cirque du Soleil was known for its innovation. Now that it was struggling, how could it continue to innovate in new directions?

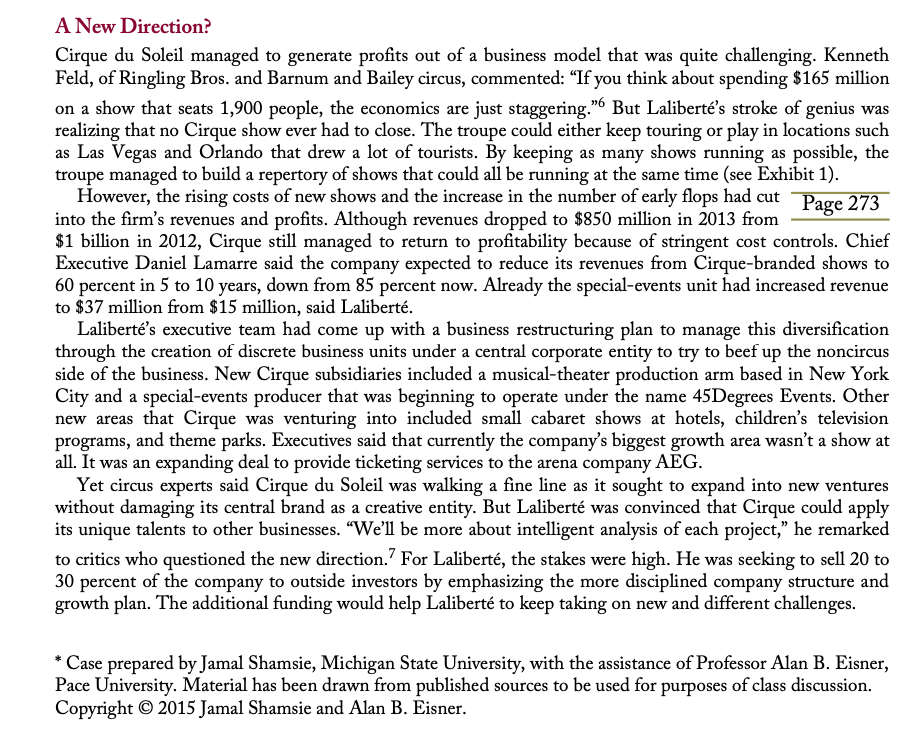

CASE 35 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL" The founder of Cirque du Soleil, Guy Lalibert, after seeing the rm's growth prospects wane in recent years, was thinking about expanding his rm in new directions. For three decades, the rm had reinvented and revolutionized the circus. From its beginning in 1984, Cirque de Soleil had thrilled over 150 million spectators with a novel show concept that was as original as it was nontraditional: an astonishing theatrical blend of circus acts and street entertainment, wrapped up in spectacular costumes and fairyland sets and staged to spellbinding music and magical lighting. Cirque du Soleil's business triumphs mirrored its high-ying aerial stunts, and it became a case study for business school journal articles on carving out unique markets. But following a recent bleak outlook report from a consultant, a spate of poorly received shows over the last few years, and a decline in prots, executives at Cirque said they were now restructuring and refocusing the businessshifting some of the attention away from the rm's string of successful shows and toward several other potential business ventures. Cirque du Soleil had also suffered other setbacks. Plans for a new show that would have been based in Dubai fell through after the city had nancial problems that stemmed from the 2003 recession. Cirque also recently suffered its rst death during a performance, when an acrobat tumbled 94 feet during a stunt in a Las Vegas performance of the show Ka in 2013. After a hiatus of more than a year, Cirque brought a revamped version of the stunt back to the show with more stringent safety measures. \"The recent struggles,\" said Chief Executive Daniel Lamarre, \"certainly brought a lot of humility to the organization.\"1 For the rst time in recent history, Cirque du Soleil failed to generate a prot in 2013. Its market had dropped 20 percent from $2.7 billion in 2003. In recent interviews with The W31! Streetjomal at Cirque du Soleil's sleek headquarters in Montreal, top executives, including founder and 90 percent owner Guy Lalibert, revealed rare details of the rm's nancial status and new business plans. The company was seeking to position itself as an attractive bet as Lalibert began to look for investors to buy a signicant portion. Debate swirled over whether Cirque du Soleil should return to its roots or aim for constant reinvention. At the end of 2011, Bain SC (30., contracted by Cirque, reported that Cirque's market had hit saturation and the company needed to be careful about how many new shows it should add. Bain suggested Cirque seek growth by moving its concept to movies, television, and nightclubs. \"Guy Lalibert always said we are a raritybut the rarity was gone,\" said Marc Gagnon, a former top executive in charge of operations for Cirque du Soleil, who left in 2012.2 Starting a New Concept Cirque du Soleil developed out of early efforts of Guy Lalibert, who left his Montreal home at the age of 14 with little more than an accordion. He Uaveled around, trying out di'erent acts such as re-eating for spare change in front of Centre Pompidou in Paris. When he returned home, he hooked up with another visionary street performer from (bebec, a stilt-walker named Gilles Ste-Croix. In 1932, Lalibert and Ste-Croix organized a street performance festival in the sleepy town of Baie St. Paul along the St. Lawrence valley. By 1984, Cirque du Soleil was formed with nancial support from the government of Quebec as banks were reluctant to support the band of re-eaters, stilt-walkers, and clowns. Its breakthrough 1937 show We Reinvent the Circus burst on the art scene in Montreal as an entirely new art form. No one had seen anything like it before. Lalibert and Ste-Croix had turned the whole concept of circus on its head. Using story lines, identiable characters, and an emotional arc, Cirque du Soleil embodied more than a mere collection of disparate acts and feats. Despite its early success, Cirque du Soleil was struggling nancially. It took a gamble on making its debut in the United States as the opening act of the 1937 Los Angeles Festival. Cirque managed to sell out all of its 868 performances, which were run in a tent on a lot adjacent to downtown's Little Tokyo. Its success in Los Angeles led the troupe to open shows across the U.S. in cities such as Washington, San Francisco, Miami, and Chicago. Soon afterward, Cirque du Soleil perfomted in Japan and Switzerland, introducing its concept to audiences outside North America. In 1992, Cirque du Soleil took a show called Nowell: Experience to Las Vegas for the rst W time. It was performed under the big top in the parking lot of the Mirage. The success of this show led to the building of a permanent theater at Treasure Island for a show called Myrrei-e, a nonstop perpetual-motion kaleidoscope of athleticism and raw emotion that thrilled audiences. It became the first of the troupe's permanent shows and led to several others that opened in other hotels along the Las Vegas strip. The most spectacular of these was 0, which included acts that were performed in a 25-foot-deep, 1.5 million gallon pool of crystal clear water in a custom-built theater at Bellagio. By the end of 2011, Cirque du Soleil had 22 showsseven of them in Las Vegas. It had become an international entertainment conglomerate with 4,000 employees working in oices around the world. It had established its headquarters in a $40 million building in Montreal, where all of Cirque's shows were created and produced. Much of the building was devoted to practice studios for various types of performers and to the costume department that outtted performers in fantastical hand-painted clothes. Cirque du Soleil recruited many types of talent, among them acrobats, athletes, dancers, musicians, clowns, actors, and singers. Growing with the Concept Cirque du Soleil hired key people from the National Circus School in its formative years in order to develop its concept of the contemporary circus. Its rst recruit was Guy Caron, the head of this school, as the Cirque's artistic director. Shortly afterward, the troupe recruited Franco Dragone, another instructor from the National Circus School, who had been working in Belgium. Dragone brought with him his experience in cammedia defray-re techniques, which he imparted to the Cirque performers. Together, Caron and Dragone were behind the creation of all the Cirque du Soleil shows during the firm's formative years, including Saimbama, Mimi's, Alegria, Quidam, and the extravagant 0. Under the watchJl eye of Lalibert, Cirque developed its unique formula that would dene its shows. From the beginning, it promoted the whole show, rather than specic acts or performers. Cirque eliminated spoken dialogue so that its shows would not be culture-bound, using instead strong emotional music that was played from the beginning to the end by musicians. Performers, rather than a technical crew, moved equipment and props on and off the stage to avoid disrupting the momentum as the show transitioned from one act to the next. Most importantly, the idea was to create a circus without a ring or animals, as Laliberte believed that the lack of these two elements would draw the audience more into the performance. Even though Laliberte and his creative team were clearly innovative in their approach, they were not reluctant to obtain inspiration from outside sources. They drew on the tradition of pantomime and masks from cirCuses in Europe. They learned about blending presentational, musical, and choreographic elements from the Chinese. Caron readily admitted that Cirque took everything that had existed in the past and pulled it into the present, so that it would strike a chord with present-day audiences. All of the Cirque du Soleil shows were originally developed to be performed under a Grand Chapiteau, or Big Top, for an extended period of time, before they were modied, if necessary, for touring in arenas and other venues. The troupe's Grand Chapiteau were easily recognizable by their blue and yellow coloring. The facility could seat more than 2,600 spectators and was accompanied by smaller fixtures that were necessary to accommodate practice sessions, food preparation, and administrative services. However, after the contract to develop Myrre're for Treasure Island in Las Vegas, Cirque began to develop shows that were to be performed on a more permanent basis in specially designed auditoriums. Losing Its Touch Cirque du Soleil continued to expand even as the recession cut into demand. It launched 20 shows in the 23 years from 1984 through 2006, none of which closed during that time other than a couple of early ones. Over the next six years, however, it opened 14 more shows, 5 of which opped and closed early. The reasons for the failures differed. One show, Zarkana, couldn't make enough money to cover its production costs playing in New York City's 6,000-seat Radio City Music Hall. Iris, in Los Angeles, played in Hollywood, a seedy neighborhood that despite heavy tourist trafc was commercially marginal. Zaia, in Macau, simply didn't appeal to local audiences. Perhaps more troubling, the company's nearly perfect record of producing artistic successes began to waver. Vim Em'r and Banana 85pm?! were among several Cirque shows that garnered terrible reviews. Both shows closed quickly. \"Shows like that diluted the brand," said Patrick Leroux, a professor at Montreal's Concordia University who had closely studied Cirque du Soleil. 3 One problem, said Cirque du Soleil executives, was that audiences didn't understand the differences among various shows carrying the Cirque brand. As a result, many people would dismiss the opportunity to see, for instance, the show Totem thinking they had already seen something similar in the older Varekai. On the other hand, Cirque tried to move in different directions with each of the new shows that it developed. "We're constantly challenging ourselves," Laliberte said. Audiences, however, complained that some newer shows were not as focused on the acrobatic feats that they had come to expect and enjoy from Cirque. By August 2012, Laliberte was concerned and convened a five-day summit for executives at his estate outside Montreal. There, he and others drew up plans to lay off hundreds of executives and performers and pare the number of big new touring circus shows Cirque produced. The cuts began soon after and continued through 2013 and amounted to around $100 million of savings, according to Laliberte. They included everything from giving out fewer suede anniversary jackets for employees to cutting out child performers and tutors. Laliberte also reexamined core production costs. The payroll for Cirque's show O, in Las Page 272 Vegas, for instance, had ballooned thanks to a surge in contortionists. "I said, 'Why do we need six contortionists?" Laliberte, 55, recalled while chain smoking in his office. In addition to the layoffs, Cirque also suffered a blow to morale when acrobat Sarah Guyard-Guillot was killed in 2013 during a performance. The company overhauled the show's finale, a "battle" staged on a vertical wall with performers suspended from motorized wire harnesses. After the performer's death, Cirque continued to stage the show, replacing the live finale with a videotape of the scene from a past performance. EXHIBIT 1 Cirque du Soleil Shows Grand Chapiteau & Arena Shows Resident Shows 1990 Nouvelle Experience 1993 Mystere" Treasure Island, Las Vegas 1992 Saltimbanco 1998 0' Bellagio, Las Vegas 1994 Alegria 1998 La Nouba Downtown Disney, Lake Buena Vista 1996 Quidam" 2003 Zumanity New York New York, Las Vegas 1999 Dralion 2005 Ka' MGM Grand, Las Vegas 2002 Varekai" 2006 Love" The Mirage, Las Vegas 2005 Corteo" 2008 Zaia The Venetian Macao 2006 Delirium 2008 Zed Tokyo Disney Resort, Tokyo 2007 Kooza' 2008 Criss Angel Believe Luxor, Las Vegas 2007 Wintuk 2009 Viva Elvis Aria Resort & Casino, Las Vegas 2009 Ovo 2011 Iris Dolby Theatre, Los Angeles 2009 Banana Shpeel 3 Michael Jackson: One" Mandalay Bay & Resort, Las Vegas 2010 Totem' 2014 JOYA' Riviera Maya, Mexico 2011 Michael Jackson: The Immortal World Tour 2012 Amaluna' 2014 Kurios: Cabinet of Curiosities"A New Direction? Cirque du Soleil managed to generate prots out of a business model that was quite challenging. Kenneth Feld, of Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey circus, commented: \"If you think about spending $165 million on a show that seats 1,900 people, the economics are just staggering."6 But Laliberte's stroke of genius was realizing that no Cirque show ever had to close. The troupe could either keep touring or play in locations such as Las Vegas and Orlando that drew a lot of tourists. By keeping as many shows running as possible, the troupe managed to build a repertory of shows that could all be running at the same time (see Exhibit 1). However, the rising costs of new shows and the increase in the number of early flops had cut W into the rms revenues and prots. Although revenues dropped to $850 million in 2013 from $1 billion in 2012, Cirque still managed to return to protability because of stringent cost controls. Chief Executive Daniel Lamarre said the company expected to reduce its revenues om Cirque-branded shows to I50 percent in 5 to 10 years, down from 35 percent now. Already the special-events unit had increased revenue to $37 million from $15 million, said Laliberte. Lalibert's executive team had come up with a business restructuring plan to manage this diversication through the creation of discrete business units under a central corporate entity to try to beef up the noncircus side of the business. New Cirque subsidiaries included a musical-theater production arm based in New York City and a special-events producer that was beginning to operate under the name 45Degrees Events. Other new areas that Cirque was venturing into included small cabaret shows at hotels, children's television programs, and theme parks. Executives said that currently the company's biggest growth area wasn't a show at all. It was an expanding deal to provide ticketing services to the arena company AEG. Yet circus experts said Cirque du Soleil was walking a ne line as it sought to expand into new ventures without damaging its central brand as a creative entity. But Lalibert was convinced that Cirque could apply its unique talents to other businesses. \"We'll be more about intelligent analysis of each project,\" he remarked to critics who questioned the new direction? For Laliberte, the stakes were high. He was seeking to sell 20 to 30 percent of the company to outside investors by emphasizing the more disciplined company structure and growth plan. The additional funding would help Lalibert to keep taking on new and different challenges. " Case prepared byJamal Shamsie, Michigan State University, with the assistance of Professor Alan B. Eisner, Pace University. Material has been drawn from published sources to be used for purposes of class discussion. Copyright 2015 Jamal Shamsie and Alan B. Eisner