Question

Connor Formed Metal Products case solution At the close of 1990, Bob Sloss, president of Connor Formed Metal Products, reflected on his accomplishments since taking

Connor Formed Metal Products case solution

At the close of 1990, Bob Sloss, president of Connor Formed Metal Products, reflected on his accomplishments since taking the helm of his family company in 1984. Thecompany,asmall custom metal spring and stampings manufacturer, had followed a steady but slow course since its founding. When Sloss became president, however, he was determined toshakethingsup.Now, after six years of hard work and significant investment, Sloss had come a long way but believed additional changes still needed to be implemented.

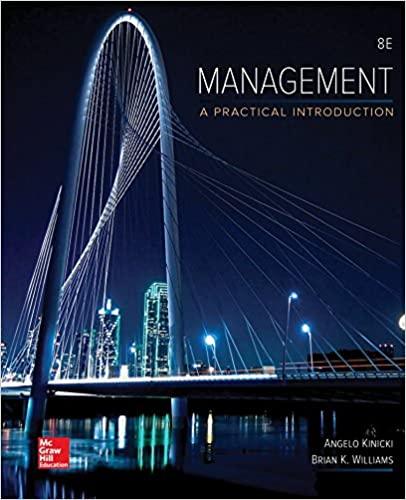

One recent change made by Sloss was to hire Michael Quarrey as Connor's human resource and information systems manager. Quarrey, who had a bachelor of science degree in computer science and an MBA and had worked at the National Center for Employee Ownership, was given the mandate to develop an order tracking system that would support Sloss's goal of empowering workers with information. (See Exhibit 1 for a 1990 organizational chart.) The system significantly changed access to and availability of information regarding the process for designing, manufacturing, selling, and servicing products. At the close of 1990, the system had been up and running successfully in the Los Angeles division for six months. Sloss now hoped to push the technology out to the other divisions in an attempt to improve the firm's profitability.

Company and Industry Overview

Connor manufactured metal springs and stampings for large U.S. original equipment manufacturers. Approximately 20% of Connor's business was producing coiled springs, which were "commodity-like" in their composition and manufacture; the remaining 80% was metal stampings, complex wire forms, and assemblies, all of which varied widely in design and therefore required significant engineering expertise to produce. Connor's competition, fragmented around product lines, comprised 600-700 primarily owner-operated job shops, most of which had an average of 20-30 employees. Customers typically chose their suppliers based on price, particularly since quality and service were notoriously poor within the industry.

In 1947, Joe and Henry Sloss, owners of a family hardware business, purchased Connor as an investment. The Sloss brothers managed the company from afar until the early 1960s when they sold off their hardware business.The family continued to expand Connor, and by the 1960s they had opened divisions in San Jose, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Portland, Oregon. During this time and through the 1970s, the company was run by Vice President of Operations George Halkides, who maintained tight control over the company through traditional accounting and control systems split between Connor's San Francisco corporate headquarters and the Los Angeles plant. When Halkides retired in the early 1980s, Joe Sloss's son, Bob Sloss, was in line to fill the position. At age 34, Sloss had worked at the company since 1972. Short on experience but long on enthusiasm, Sloss enrolled in Stanford's summer executive education program. Describing himself as the "wild-eyed dissident," Sloss recalled his experience:

Halkides had taken a conservative, bottom-line approach to run the company. Connor had no debt, and it was a typical slow-growth, low-investment spring company. The Stanford program catalyzed me because I learned how progressive businesses were changing due to new technology and foreign competition. I realized that Connor could either keep plugging along and eventually get lost, or we could really turn the company around andsetitapart from the competition.

When Sloss took over, he recognized that the company could not survive by maintaining its traditional way of doing business. Offshore competitors, many with lower cost structures andsuperior product quality, had entered the U.S. market and were stealing market share from the more traditional small-job shops, which had supplied the industry in the past. Manyofthese offshore firms were also attempting to buy the larger, more successful U.S. competitors as a way of entering the market. To respond to these threats, Sloss drove the company through significant change. In 1984, Connor opened a new facility in Dallas, Texas. That same year, Sloss decentralized the company, turning day-to-day authority over to the plant managers. Sloss repositioned Connor as a service-oriented business, which would focus on providing custom-developed metal stampings and wire forms that would be "100% reliable." To reach this goal, he bought new machinery and established a statistical process control system. To increase Connor's technical expertise, he hired engineers for the first time in Connor's history.

Sloss was awarethatproperly motivating employeeswas equallyimportant.As aresult,he raised wages, established a quarterly cash bonus system, and set up an Employee Stock Ownership Program (ESOP). To convey the company's new identity to the outside world, Sloss changed the company's name to Connor Formed Metal Products from its previous name, Connor Springs. He printed new marketing materials, updated sales presentations, and produced a professional videotape on the company.

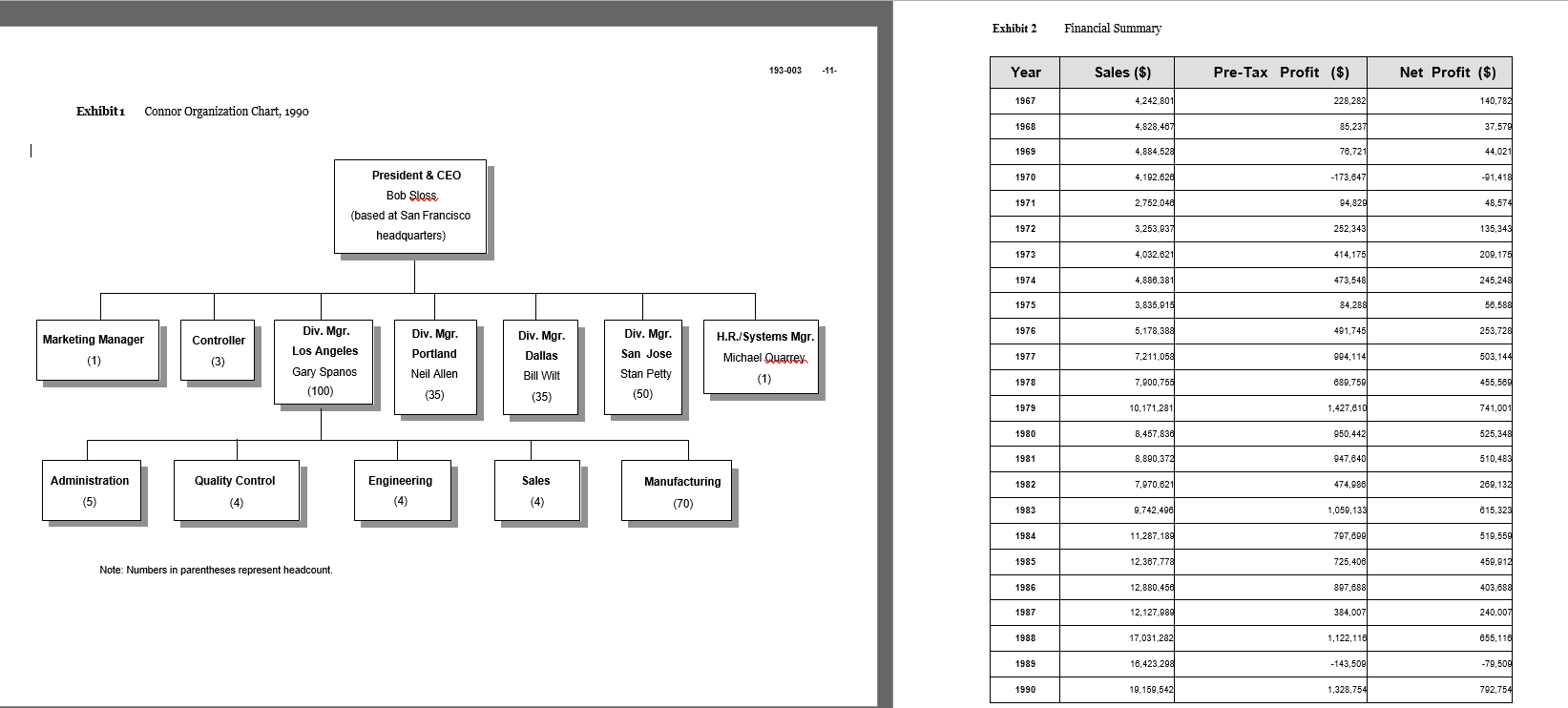

Word of Connor's new image and quality quickly spread throughout the industry, and the company became a vendor to large companies such as Honeywell, Motorola, and Hewlett-Packard. Shipments rose from under $8 million in 1982 to over $17 million in 1988. Despite these positive signals, however, Connor was not able to see the results in the bottom line (seeExhibit2).Andwhile the closing of the Phoenix plant andthetransferofitsemployeestoDallas had accounted for much of the company's 1989 losses, the Dallas plant had not been profitable in its five years of existence, and the Los Angeles division was seeing tough times as well. Connor's other divisions in Portland and San Jose were making a significant profit, but the overall results still had not reached Sloss's goals.

TransformingConnor

Structure

Before Bob Sloss's presidency, Connor had been divided into two regions, North and South; the Phoenix plant had reported to Los Angeles while the Portland plant had reported to San Jose.Not only had this perpetuated a structural hierarchy which Slossdisliked,butcustomerswerebeing traded between plants based on the self-interestofthelargerplantsinCaliforniarather than the needs of the customer.

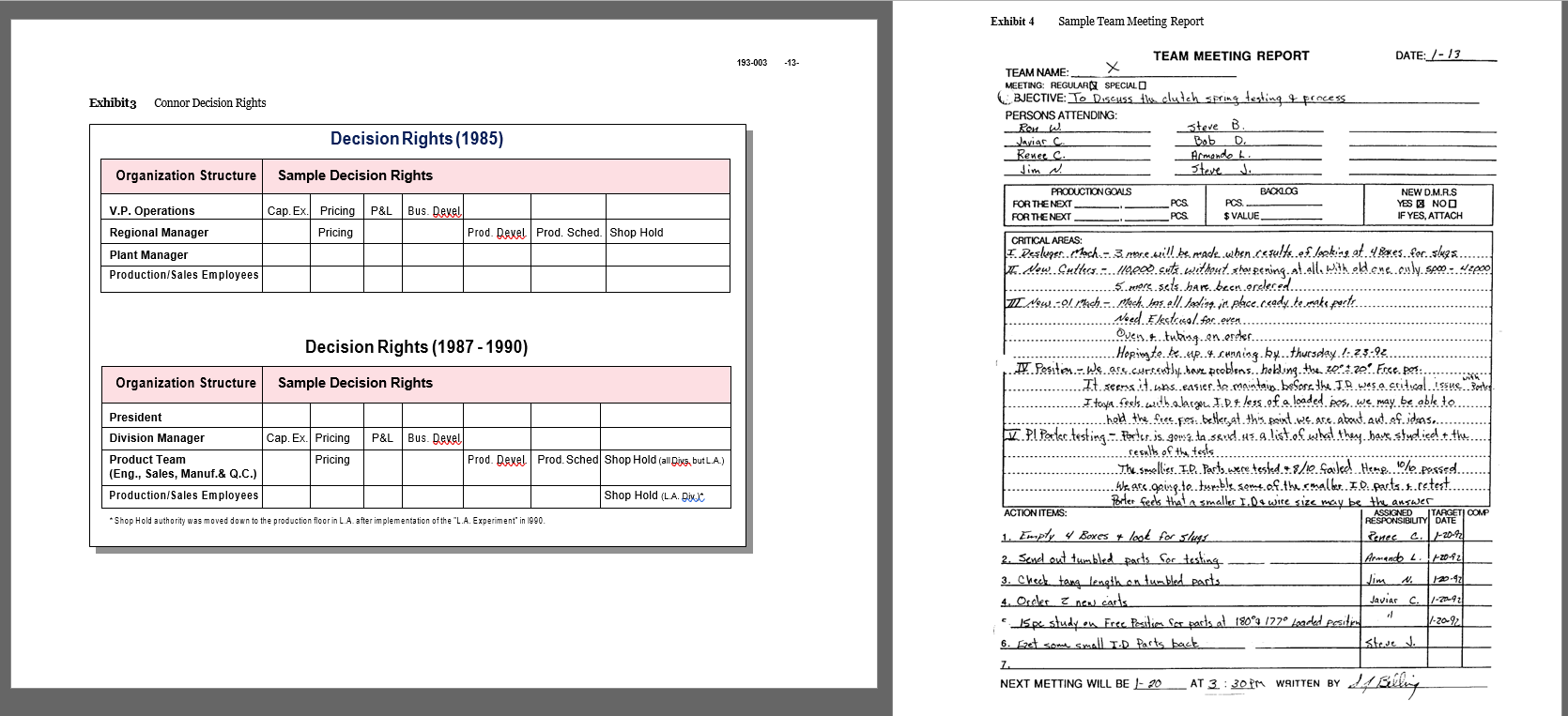

Upon his arrival in 1984, Sloss's first move was to decentralize the company into four autonomous divisions, giving each full profit and loss as well as capital expenditure responsibility(see Exhibit 3). In his move away from a hierarchical organizational structure, Sloss established a "hands-off" approach to overseeing the business. At the division level, each plant maintained administrative, quality control, engineering, sales, and manufacturing functions.Product pricingwas jointly determined by engineering, sales, and division management. Production scheduling was run by the division's production manager. Sloss placed a particular emphasis on the engineering aspect of the business process. Engineers, production supervisors, and salespeople were teamed together and were expected to communicate closely as each order moved through the production and distribution process.

The Los Angeles division was the largest Connor plant, with 100 employees and salestotalling $10 million. The plant specialized in high-volume products for the diverse industrial businesses of southern California. Division Manager Gary Spanos had been with Connor for close to 20 years. Originally hired by Halkides, Spanos had managed both the PortlandandSanJoseplants. In 1986, seven years after Halkides' departure, Spanos returned to Los Angeles with the mission of restoring the plant to its former role as profit leader for the company.

The San Jose division, with 60 employees, was run by MBA graduate Stan Petty. Petty had succeeded Spanos as manager of the Portland division and then succeeded Spanos again when he became manager of the San Jose division. In the 1980s, the San Jose plant had diversified from its traditional product lines of springs and stampings to specialize in the manufacturing of short-run prototypes for high-technology Silicon Valley companies. Petty was known for his "bottom line" approach to management, and the San Jose division had achieved record profit margins during Petty's tenure as manager.

The Portland division consisted of approximately 30 employees and served primarily Northwest-based trucking companies and related parts manufacturers. Thedivisionwasrunby Neil Allen, who had been in the industry for 20 years and whose father hadalso workedforConnor. While inthepast thePortland division had been perceived asbeing lesssophisticatedthan the other Connor divisions, it had made efforts to increase the level of technical support available to customers within the past few years and aggressively pursued new "world-class" customers.

The company purchased the Dallas plant soon after Sloss assumed control in 1984. By 1989, when the plant had failed to make a profit, Sloss decided to merge the Dallas and Phoenix plants and relocate both to a new site in Dallas.Sloss brought in Bill Wilt from the Phoenix plant to run the new Dallas division. Wilt had had a long career with Associated Spring, the world's largest spring maker, and was known for turning around losing operations.

When considering what aspects of the company to change as he moved forward, Sloss was confident that the autonomous division structure needed to remain intact because it provided a competitive advantage:

There is no question that we could move everything under one roof, but we would lose our local customers. We would also probably ruin the company's culture, which is based on working in small groups. Our plans are to continue to develop our regional markets. There is particular potential in Mexico for both ourLos Angeles and Dallas plants. We would even consider opening up new divisions if there was enough demand.

Control

Upon assuming control of the company, Sloss recognized that Connor's control systems needed to be realigned. Halkides hadmaintainedadetached,top-downmanagementapproach and shared minimal information with employees. In contrast, Sloss believed in actively involving employees in the business through the exchange of information. Sloss recalled Halkides' approach:

Halkides had created an environment of traditional loyalty, but he rarely got the employees on the floor involved with what the business was doing. He managed by "the need to know." And, to him, when it came to the shop employees, they didn't need to know much. There were never any employee meetings with or without management. They just did their jobs out in the shop.

I don't believe in a stringent managerial hierarchy. I want to involveasmany employees as possible in the decision-making process because I really believe that the more employees know, the better off the company will be. I want them to have access to all kinds of information, which they wouldn't have if they were working at a company of the "old school." Especially as an ESOP company, we are obligated to operate this way.

To promote the sharing of information within each division, Sloss encouraged the division managers to hold weekly staff meetings with 12-15 employees from engineering, sales, customer service, quality control, production management, and personnel. The leadership of these meetings was determined on an informal rotation basis. In addition, weekly production meetings were scheduled and run by the production manager of the plant. In these meetings, the heads of each department reviewed the production schedule for the upcoming week. Product teams met on an ad-hoc schedule, often once a week. In all meetings, the designated leader was responsible for filling out a meeting report (see Exhibit 4). These reports were stored in a binder located in the meeting room and were available for reference to anyone in the company. Each division also held monthly departmental meetings with the division manager. Division managers' meetings were held quarterly, and Sloss visited each plant regularly.

Halkides had closely monitored all aspects of the company's information flow; for example, he signed his initials on each invoice. Sloss, in contrast, chose to review only a handful of key indicators such as sales-in, backlog, and payroll. He believed that if he and the divisionmanagers delegated much of this responsibility, details could be handled with more speed and accuracy.

Through an extensive statistical process control program begun in Portland and carried to all the plants, employees were trained to monitor and take responsibility for the quality of their own work. In Dallas, Wilt carried this concept further by initiating plant-wide incentives based on "managing the numbers." In addition to monitoring quality, Dallas employees recorded their progress on bulletin boards, tracked their own efficiency, on-time delivery, and safety. Employees received monthly bonuses based on their improvements.

Sloss also looked outside Connor for information and feedback on the company's progress and overall strategy. Encouraged by Motorola, the company participated annually in the National Baldrige Award competition. Sloss made it a point to learn as much as possible from customers,other ESOP companies, and trade associations through which he and other Connor employees networked frequently.

Culture

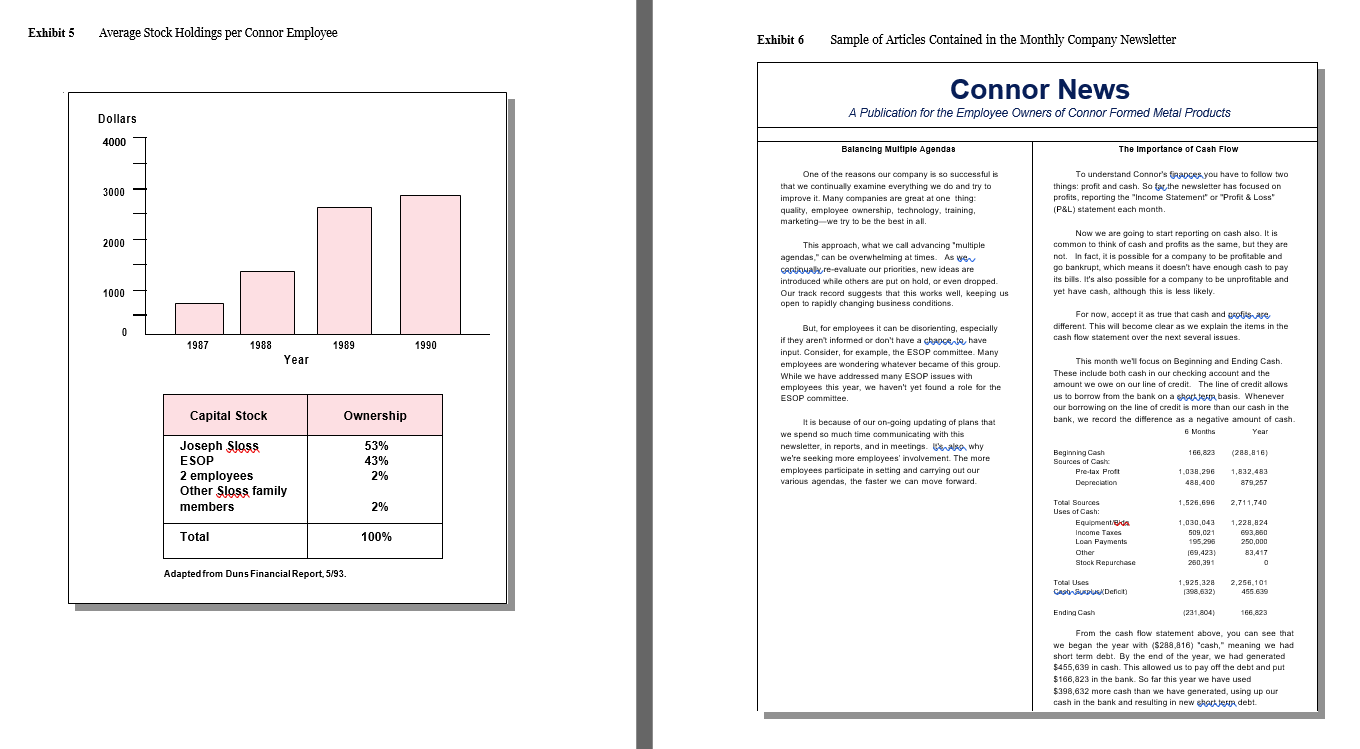

The ESOP Sloss established in 1986 had grown steadily (see Exhibit 5). Obsessed with chipping away at Connor's old-fashioned, secretive style of management, Sloss insisted that once employees were actual owners of the company, they should act like owners as well. Sloss and the division managers explained the company's financial statistics to employees, walkedaroundthe plant answering questions, and made themselves available for such things as "lunch with the boss" meetings. He also established a monthly company newsletter and beganholdingperiodicon-site and off-site team-building sessions (see Exhibit 6).

Incentives and Rewards

In keeping with his desire to empower all levels of the organization, Sloss instituted anumber of incentives and rewards for lower levels of the company. Prior to Sloss's arrival, Connor maintained standard wages with added incentives only for top executives. Sloss immediately increased the company's base salaries to be the most competitive in the industry and implemented a quarterly cash bonus system. Division managers began to occasionally award bonus checks of up to a few hundred dollars to employees who had shown "exemplary performance."

Employee response to such changes was extremely positive. Mary Kunkel, San Jose's office manager, explained:

I am pretty pro-Connor. I really enjoy the company. I like being an ESOP company because I think you tend to take more pride in your company and your work.If it's the end of the month, we will seriously go out to the shop and say,"What do you have to get out today?"Give us tacky board, give us the parts, we will put them in the little box and get them out.Because we want that money on the shipping log, we want more bonuses, we want more profit. I started here when I was young enough so that I can have a lot of money by the time I retire. Either thator I will have an awfully nice boat on a lake!

Sloss also worked to attract the "best and the brightest" to Connor. He recruited at top engineering schools to find younger, high potential employees. He believed that Connor promised those who were interested in a challenge a valuable experience with a competitive salary.

Information Systems

When Sloss took over in 1984, the extent of the company's information technology was an IBM System 34 mini-computer located at the corporate office, which produced the company's payroll, accounts receivable, and accounts payable. Within the operating divisions, engineers produced estimates by hand, shop orders were typed out on a slip ten carbons deep, sales information was kept in large, loose-leaf notebooks, and order slips were returned following production covered with grease and finger smudges. In an effort to reduce some of this paperwork, Sloss in 1985 brought IBM System 36s into the Los Angeles, San Jose, and Portland plants. Employees used the system for basic office tasks but found the "canned" software too generic for the more complicated procedures such as estimating and shop ordering.

Each division responded to the IBM System 36 differently; success with the system could be traced to the level of computer proficiency within each division at that time.InthePortland division, where a number of employees were experienced computer users, the System 36 was used for a variety of tasks. But the San Jose division system had not been used since itsinstalment, primarily because there were no employees who felt comfortable using mini-computers. The Los Angeles division used the System 36 for basic office automation and had even upgraded to the System 38 for more capacity. Yet they still found the system too unwieldy for anything other than basic administrative procedures.

The Los Angeles Experiment

When considering how to move forward with information management and computers, Sloss noted what Petty had done with personal computers after transferring from Portland to San Jose in 1986. Petty, a strong advocate of increased efficiency through the use of computers, had created a system using personal computers and manufacturing software called "Job Boss." This system, well regarded by employees who used it, automated almost all of the division's office tasks (e.g., estimating, order entry, accounts receivable, and purchasing). At the same time, the Portlanddivision was also experimenting with personal computers. As a result, Sloss began to consider using personal computers combined with custom software to help make the business more profitable. Sloss recalled:

I wanted to begin doing things on purpose. I wanted to know which department's machinery produced the best margins. Iwanted tohave theanswers to questions like, "Are we more profitable manufacturing parts for the irrigation industry or the aerospace industry?" I also wanted to know whether there was a similarity among the kind of customers that bought from us. Could we go out and find more of them? All of this was information that the division managers would know about. But I wanted to know it empirically instead of by gut feelandIbelieved we could do it using the PCs and custom software.

During this same period, Sloss was interviewing candidates to fill the newly created position of human resource manager when he received a call from Michael Quarrey, who had just left a small manufacturing company in Worcester, Massachusetts, in hopes of finding a job where he could fulfil his long-term career goal. After having worked at the National Center for Employee Ownership and doing extensive research on ESOP companies, 1 Quarrey wanted to test ways of empowering employee owners with information. When his previous employer was unable to set upan ESOP, Quarrey decided to find a company that already had one. He contacted Sloss andexplained that with his college-level computer programming expertise and his ESOP background, he could serve as Connor's human resource manager and help Sloss find a solution to Connor's information problem. Quarrey remembered:

Sloss was going through a very typical thing for an ESOP company executive. He or she gets to a point and says, "We now have given our employees33% ownership, yet the employees are responding to us the same as they always have." While Sloss had expected employee ownership to improve Connor's performance, overall margins weren't getting better, and in Los Angeles they were getting substantially worse. Here was someone calling him on the phone out of the blue, saying, "I have a theory about how to do things. I don't know anything aboutthe company. Still, I have a very strong conviction that information and ESOPs should be married together and I have some tools which can help." For me, the reward would be experimenting in Connor's "lab" to test employee ownership and ways of empowering people with information.

After listening to Quarrey's pitch, Sloss decided to go forward. Since Los Angeles was doing poorly and it was the largest plant, the possibility of computerizing its information flow seemed like a logical step. Sloss had spoken with Spanos about the idea before. Still, Spanos had taken an "anti-technology" view, claiming that information systems were too inflexible for the custom work in which Connor specialized. Sloss believed, however, that if he could position Quarrey's role as supporting employee ownership, his added responsibility of writing custom softwarewouldbebetter received by Spanos as well as the other employees. Sloss explained:

The idea of a little company like ours hiring a computer programmer was mind-boggling. But I was convinced it was the way to go and we could justify Michael's payroll expense by having him work on two things, software and theESOP.

Beginning work in August 1989, Quarrey was instructed to work on increasing the Los Angeles division's employee involvement in the ESOP while also developing an order-tracking and costing system for the plant. The system was developed using a relational database PC package called "Clipper," which was specifically designed to support distributed database management over a network. The cost of the database software was approximately $500. Quarrey's strategy was to begin development of the system by creating the module that would support the estimating portion of the product/service delivery process. Once this was in place, he could build in shop order and invoice capabilities, and ultimately add in all of the administrative procedures included in the manufacturing process. Before long, Quarrey was designing features that set the system apart from a typical "automated" process. Each electronic shop order contained "notes" areas, where departments could make comments about a particular job as it moved through the manufacturing process. "But it was Roy Gallucci, a blunt-spoken machinist in Connor's coiling department, who may have had the biggest impact on the new system," stated John Case in a recent article on the company:2

The machinist's message to the boss was simple.At least one computer shouldbe out in the shop. Blue-collar employees should have the ability not only to enter comments about a job but to force the office somehow to pay attention. He didn't know exactly how it might work; but if the company was going to put in a whole new system, it had better do it right.Bingo, Sloss thought:Gallucci was touching on a perennial complaint that the office never listened to the shop. Here was achance to deal with it.

Thanks to Roy Gallucci, every employee has full and instant access to data about the jobs he or she is working on?not just the customer's name and the specs but a full history of the job to date, special notes or instructions from engineering or customer service, and management information once thought of as sensitive, such as price and margin. An employee who spots a problem with a job can go to the computer and put a "shop hold" on it. Until the engineering department investigates?and makes a formal written disposition of the problem?the software won't allow Connor to take any new orders for the same part.

In one recent six-week period, Quarrey counted 117 holds emanating from machine operators and their supervisors. "This grinding can only be done by A-1 Surface Grinding," read one, adding the address, a contact name, and the price per part that the preferred outside vendor would charge. "OK, will change themaster," responded engineering. "Change run speed from 850 pcs/hr to 650 pcs/hr," recommended another. "Changed speed from 850 pcs/hr to 700 pcs/hr," answered the not-totally-compliant engineer. Gallucci himself admits to using the feature regularly?for example, to propose sending a three-part order out for heat treating all together rather than one batch at a time. And Quarrey points out that similar holds can be put on a shop order by quality control, by engineering ("Don't allowthis estimate to become an order until we have a clean blueprint."), or by customer service ("Don't ship without clearance from us.").

As a result, employees, using the bare minimum of the "page up/down" keys, would knownot only the full history of a job to date, but also have the power to help control the production process (See Exhibit 7 and Exhibit 8 for samples of an estimate and shop order.). Quarrey explained:

The system will not allow anyone to create a report on an individual employee's productivity. All the information we collect is sorted by job number, not by employee. This was important so that the system be used not to manage people but rather the other way around?people manage the process. In keeping with his "details are delegated" approach, Sloss wasn't even networked to the system.

Each computer program was designed participatively. I spoke to people in different areas of the plant and got a general overview of how the process workedand what information they needed. Then, after going through aprogrammingphase, I would go back and show it to people to find out what they thought.After a lot of iterations of programming, implementing, and revising we came up with the most effective approaches. Functions were based around simple keystrokes (Page/Up, Page/ Down, Escape, etc.) and separate screens were made for "viewing" and "updating" data so that any employee in the shop could "view" any information without accidentally changing it.

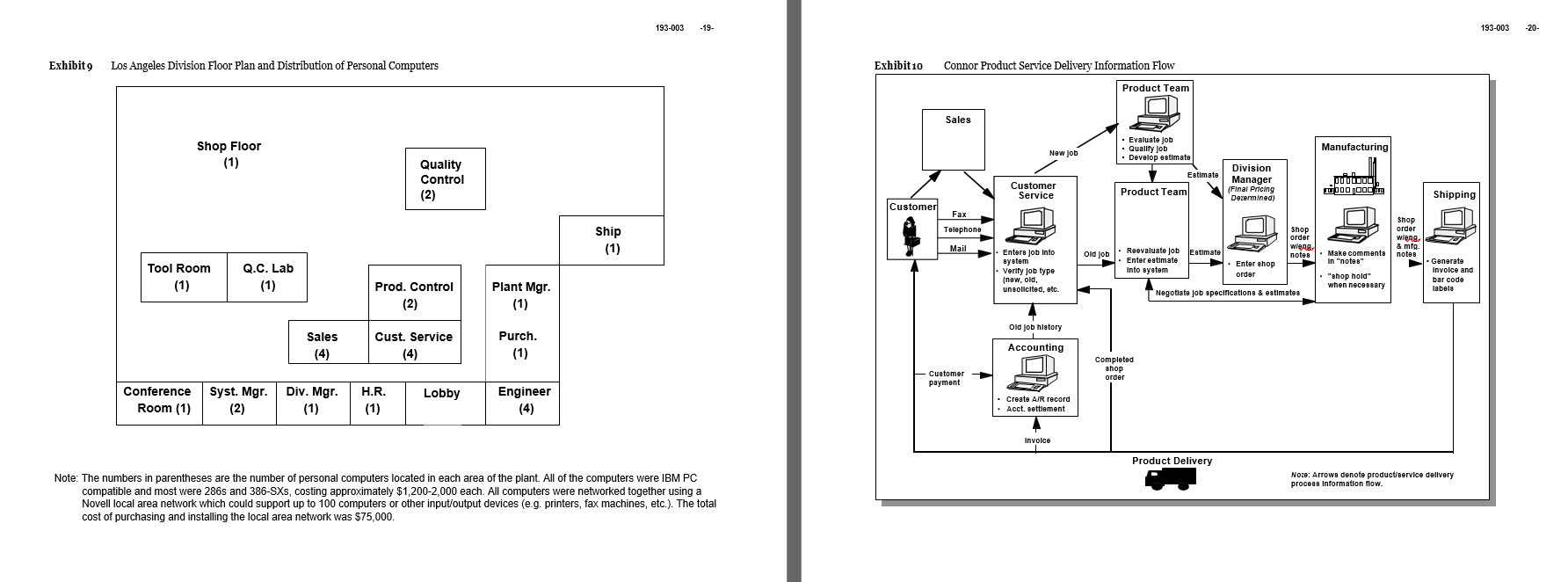

By May 1990, Quarrey had the new system up and running in the Los Angeles division (see Exhibit 9). Quarrey held a number of training sessions for the office employees as well as the shopand soon the system was being used throughout the division. Quarrey recalled:

We quickly showed the system to them and they immediately began using it. Since that day, we have never gone back to the old handwritten way of doing estimates and shop orders. Every day, someone logs in and pulls up the shop order screen.Then, all the employee has to do is type in the shop order number and hit the "page down" or other function keys until it reaches the desired screen, which can be left on all day and then the network shuts it down at night. Since I was

8

Working in Los Angeles full time, I was always around if they had questions, but generally, they just asked each other instead of asking me.

One machine operator explained:

I had never used a computer before. At first, it was really scary. But, the way it is set up, it is easy?anyone can do it. Most of the people here have just asked each other how to use it and that way we don't have to worry about feeling stupid. If there's ever a problem, you can look above the computer where there's a key to the commands.

As a result of this technology, the way the Los Angeles division did business dramatically changed (see Exhibit 10). Customer service representatives eliminated the use of carbon copies and began doing all of their work on the computer.When they received phone calls from customersabout a particular job, they immediately pulled the information up on the computer screen instead of weeding through outdated files. The engineers' estimating program reduced the calculation time for trial quotes from hours to minutes. With access to historical information, the customer service representatives did most of their own estimating without the assistance of the engineering department. And salespeople, who had previously relied on phone calls and handwritten reports to keep the shop up-to-date about each customer's needs, began using PCs exclusively.

TheNextStep

By the close of 1990, the Los Angeles division had already begun to see dramatic improvements. Just within the first few months of using the system, run speeds on a number of jobs had increased by as much as 20%. Repeat defective jobs had reduced from 14% in 1989 to 4%, and credits issued to customers fell from 4% of sales to 0.5% during the same period. Over the past two years, late jobs had declined from 10% of backlog to less than 1%. The plant's head count had dropped through attrition by 15, while its sales had risen 28% to an annual level of $10 million.

Customers began to take note of Connor's service and quality record. Annual quality ratings had soared to near perfection and customers were hiring Connor despite its higher prices. Sloss was even seeing results in his bottom line when Los Angeles' pre-tax profit rose 5% in 1990. Employee ownership had reached 42% and Connor's stock value had increased 35% in the past year.

With such positive results, Quarrey and Sloss were tempted to quickly roll out the system to the other divisions. Quarrey thought back to the meeting during which he had introduced the system to the other managers:

At that meeting, we brought in a few monitors, hooked them all up to one computer, and went through how the software worked. The meeting went for four hours that afternoon and the discussion continued through dinner. While the managers generally seemed excited, they had a lot of questions. The main one was whether the system would really work in the smaller divisions. In the Los Angeles shop where you have 100 people, thingslikethe"shophold"reallycutthrough the layers. You may not need to do that in San Jose or Portland where internal communication is already excellent.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started