Question: Create four language guidelines: two for Spanish and two for English, each with a descriptive and required component. This chapter is a brief introduction to

Create four language guidelines: two for Spanish and two for English, each with a descriptive and required component.

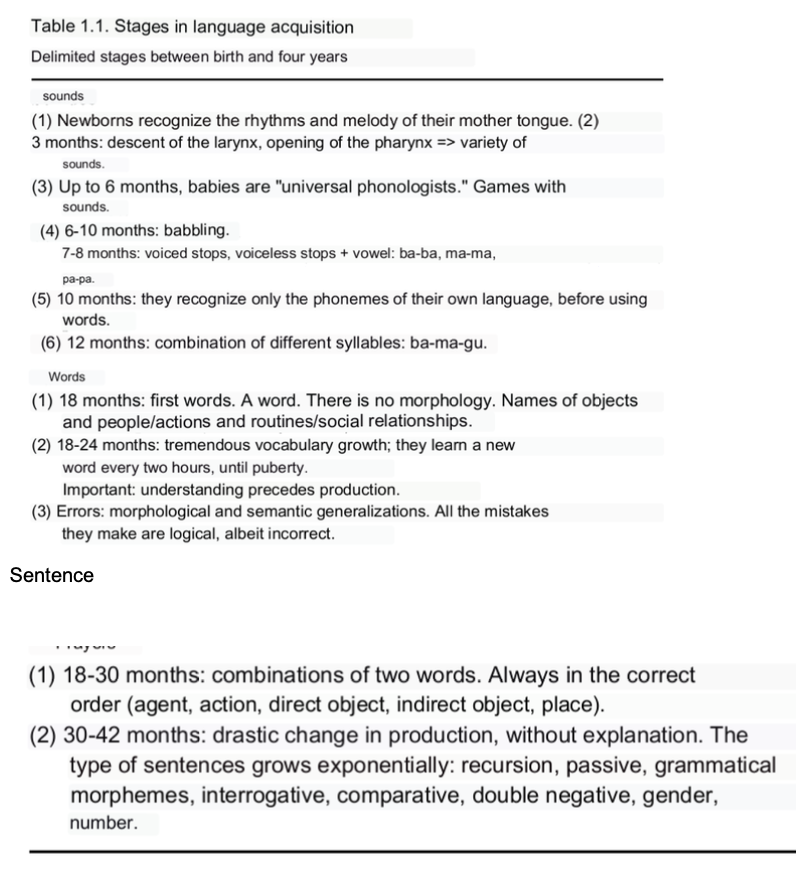

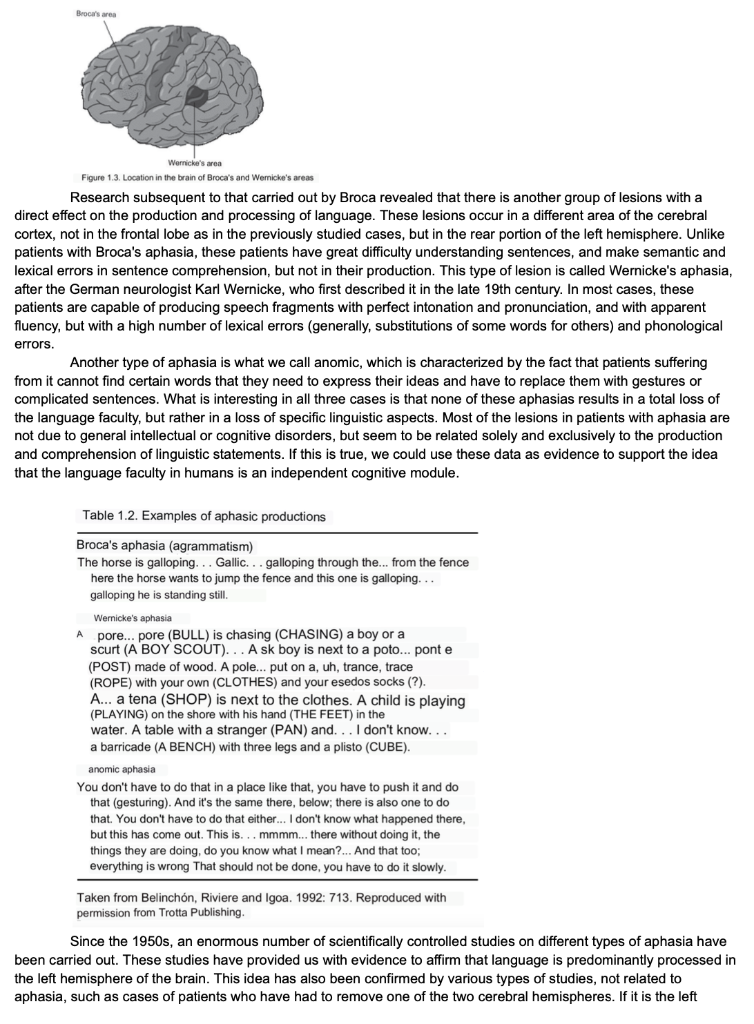

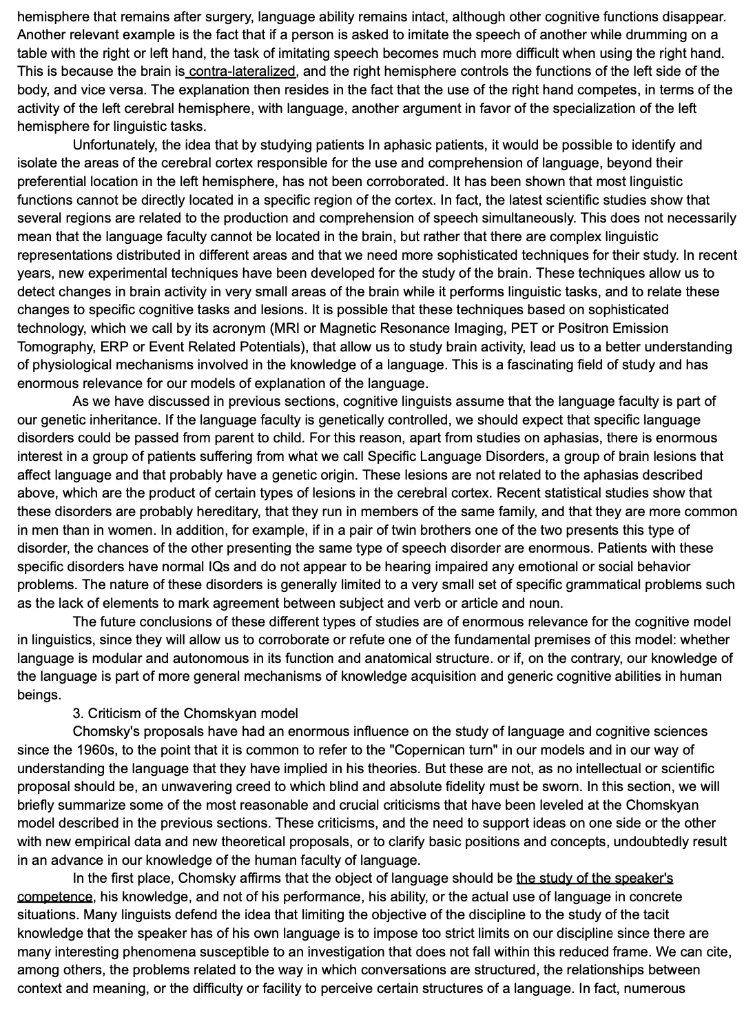

This chapter is a brief introduction to modern linguistics and to topics that will be covered in more detail in the remaining chapters of the book. The main topics we will cover are: - The different historical conceptions of language and grammar as objects of study in linguistics. - The characteristics of human language, which separate it from the communication systems of animals. - The theories about the mechanism of language acquisition in children - The relationship between the human capacity for language and the structure of the human brain - The criticisms of some of the basic postulates, both theoretical and methodological, of modern linguistics. - The definition of the central areas of the study of language to which we will dedicate each of the chapters of the book. 1. Introduction Linguistics is the discipline that studies human language. Language is possibly the most complex structured behavior we can find on our planet. The language faculty in the department is responsible for our history, our cultural evolution, and our diversity; it has contributed to the development of science and technology and to our ability to change our environment while allowing us to develop forms of aesthetic and artistic appreciation and an enormous variety of modes of interpersonal communication. The study of language is, to begin with, an intellectual challenge and a fascinating activity in itself, the attempt to piece together and unravel the workings of an enormously structured and complex puzzle, responsible in large part for what human beings are as a species. in the natural world. It is therefore not surprising that the systematic analysis of language is several millennia old. His analysis goes back to classical India and Greece and has produced an extensive and varied body of knowledge. Philosophers, philologists, grammarians, linguists, psychologists, logicians, mathematicians, and biologists have reflected for centuries on language and language from a variety of perspectives. But in addition to studying the language itself, or studying its social or historical aspects, or the relationship between the units that form it and the categories of logic, trying to analyze the meanings conveyed through it, or any of the innumerable Analytical perspectives developed over centuries, we can also study language because language is a window that allows us to describe the structure of the human mind. This way of approaching its study, which is called the cognitive perspective, although it also has its roots in classical antiquity to some extent, has undergone an enormous push since the 1960 s. In this introductory chapter, we are going to pay specific attention to this way of approaching the object of study of linguistics. 1.1. From traditional grammar to modern linguistics: prescriptive and descriptive grammars Until In the 19th century, linguistics was a fundamentally prescriptive discipline, that is, traditional grammar since ancient Indian and Greek times have been primarily concerned with describing and codifying the "right way" to speak a language. Despite Due to the change in point of view developed in recent years in the study of the human faculty of language, this type of traditional grammar, which in general tried to classify the elements of a language according to their relationship with the categories of logic, has given us provided a long list of concepts in obvious use in more modern analyses. Traditional linguistics, despite having developed over several centuries and despite encompassing a large number of different schools and very different analytical perspectives, offers a fairly homogeneous body of doctrine whose common theoretical assumptions can be summarized as follows: (i) Priority of the written language over the spoken language. The traditional view holds that the spoken language, with its imperfections and incorrectness, is inferior to the written language. For this reason, in most cases, grammarians confirm the veracity of their rules and their grammatical proposals with testimonials drawn from classical literature. (ii) Belief that the language reached a moment of maximum perfection in the past, and that it is necessary to stick to that state of language when defining the "correct" language. A traditional Spanish grammarian Introduction could, for example, defend the idea that our language reached its peak of perfection in the literature of the Golden Age, and affirm on the one hand that since then the language has only deteriorated and on the other that we should all aspire to use the language as Cervantes did. (iii) Establishment of a parallelism between the categories of logical thought and those of language, since grammatical studies were born in Greece and identified with logic. From there comes the tradition of making the grammatical category of "noun" correspond to the logical category of "substance", to that of "accident" that of "adjective", etc. The classification of parts of speech that is so familiar to us today, for example, has its origins in classical Greece. (iv) Conviction that the function of linguistic and grammatical studies is to teach to speak and write a language correctly. This conception of the function of linguistic studies deserves special attention, since it establishes a contrast between modern and traditional approaches. The prescriptive rules, which we often find in traditional grammars and second language teaching manuals, are used to help students learn how to pronounce words, when to use the subjunctive or preterite in Spanish, for example, and to organize correctly the sentences of the language we are studying. A prescriptive grammarian would wonder what the Spanish language should be like, how its speakers should use it, and what functions and uses its component elements should have. Prescriptivists thus follow the tradition of classical Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin grammars, whose goal was to preserve earlier manifestations of those languages so that readers of later generations could understand sacred texts and historical documents. A prescriptive or traditional Spanish grammar would tell us, for example, that we should say "I have forgotten" and not "I have forgotten"; that the sentence "I think you are wrong" is the correct one, instead of the frequent "I think that you are not right"; that it is more correct to say "if I said that I would not believe it" instead of "if I said that I would not believe it"; that it is appropriate to say "sit down" instead of "sit down". These grammars try to explain how the language is spoken properly, using the appropriate words with their precise meaning, and correctly, constructing the sentences in accordance with the normative use of the language. Modern linguists, on the other hand, try to describe rather than prescribe linguistic forms and their uses. In proposing suitable descriptive rules, the grammarian must identify which constructions are actually used, not which constructions should be used. For this reason, a descriptive linguist is concerned with discovering in what circumstances they are used. "I have forgotten" or "sit down", for example, and in observing that there are different social groups that favor one or another expression in conversation, while these, in general, do not appear in writing. On the contrary, a prescriptivist would argue why the use of them is incorrect. The question that arises then is: who is right: the prescriptivists or the descriptive grammarians? And, above all, who decides which uses of the language are correct? For many descriptive linguists, the problem of who is right is limited to deciding who has decision-making power on these issues and who doesn't. Viewing language as a form of cultural capital we realize that the stigmatized forms, those declared improper or incorrect by prescriptive grammars, are those typically used by social groups other than the middle classes-professionals, lawyers, doctors, publishers, and teachers. Descriptive linguists, unlike prescriptive ones in general, assume that the language of the educated middle class is neither better nor worse than the language used by other social groups, in the same way, that Spanish is neither better nor worse. Neither simpler nor more complicated than Arabic or Turkish, or that the Spanish of the Iberian Peninsula is neither better nor worse than that spoken in Mexico, or that the Australian dialect of English is neither less nor more correct than the British. These linguists would also insist that the expressions that appear in dictionaries or grammars are neither the only acceptable forms nor the ideal expressions for all circumstances. Does the language deteriorate over the generations, as claimed by some prescriptivists trying to "recover the purity of the language"? Descriptive linguists argue that, in fact, Spanish is changing, as it should, but that change It is not a sign of weakening, probably Spanish is changing in the same way that has made our language so rich, flexible, and popular in its use. Languages are alive, they grow, and they adapt. Change is neither good nor bad, just inevitable. The only languages that do not change are those that are no longer used, the dead languages. The job of the modern linguist is to describe the language as it exists in its actual uses, not as it should be but as it is, which includes the analysis of positive or negative evaluations associated with specific uses of it. 1.2. modern linguistics A crucial turn in the development of linguistics took place at the end of the eighteenth century, at a time of great progress in the natural sciences, when it was discovered that there was a genealogical connection between most of the languages of Europe and Sanskrit and other languages. languages of India and Iran. This produced an enormous development in language studies from a historical perspective and a great advance in comparative studies between close or remote languages whose objectives were both to define relationships between them and to discover the existence of families of languages characterized by common features. In this way, laws of correspondence between some languages and others, and laws of evolution between a language and its dialects were proposed. Laws of this type gave linguistics a scientific character that was not present in traditional grammar. At the beginning of the 20th century, many linguists turned their attention, following the example of the Swiss grammarian Ferdinand de Saussure, from historical (or "diachronic") studies to the synchronic study of language, that is, to the description of a language at a time. determined in time. This emphasis on synchronic studies encouraged the investigation of languages that did not have writing systems, much more difficult to study from a diachronic point of view since there were no texts that evidenced their past. The main contribution of this model The research objective was to point out that every language constitutes a system, a set of interrelated signs in which each unit does not exist independently but finds its identity and validity within the system by relation and opposition to the other elements of it. In the United States, this turn produced a growing interest in native indigenous languages and in the enormous diversity of languages on our planet, of which the Indo-European languages, the most studied until then, constitute a minor fraction. By broadening the perspective of the study, it was necessary for the linguistic methodology to also broaden its descriptive tools, since it was not excessively productive to impose the structure and categories of analysis of known and well-studied languages (Latin and English, for example) on languages whose structure was radically different. These studies contributed to showing the weaknesses of the traditional categories of analysis and proposed an analytical and descriptive model to break down the language units into their constituent elements. Some linguists, notably Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, explored the idea that the study of language could reveal how its speakers think, and focused their theories on explaining how studying the structures of a language could help us understand the thought processes of humans. In the second half of the 20th century, both the invention of the computer and the advances in the study of mathematical logic provided our discipline with new tools that seemed to have a clear application in the study of natural languages. A third step in the development of language studies in this half century was the decline of the behaviorist model in the social sciences. As in other disciplines, linguistics, especially North American, was dominated by behaviorism, which assumed that human behavior, in any of its manifestations, related or not to language, could not be adequately described by proposing the existence of states or entities determined mental states that would explain such behavior: human language cannot be described by creating models that characterize mental states, but must simply be described as a set of responses to a specific set of stimuli. Around 1950 several psychologists began to question this idea and to criticize the absolute restriction that it imposed on the creation of abstract models to describe what happened inside the human mind. In the early 1950s, and to some extent building on the developments mentioned above, a young linguist, Noam Chomsky (1928-), published a series of studies that were to have a revolutionary impact on the approach to goals and methods. of the language sciences. On the one hand, Chomsky described a series of mathematical results on the study of natural languages that established the bases of what we know as the "formal theory of language". On the other hand, this linguist proposed a new formal mechanism for grammatical description and analyzed a set of English structures under this new formalism. Finally, Chomsky published a critique of the behaviorist model in the study of language, based on the idea that language cannot be a mere set of responses to a given set of stimuli, since one of the characteristics of our knowledge of the language it is that we can understand and produce sentences that we have never heard before. Since the 1960s, Chomsky has been the dominant figure in the field of linguistics, to such an extent that we can affirm that a large part of modern studies are either a strict defense of his ideas and of the formalisms he used proposed, or studies of language based on a rejection of the basic postulates of his theory. For this reason, in this introductory chapter, we are going to review what are the postulates of his theory and what are the criticisms that have often been leveled against it. Before discussing Chomsky's ideas about language, it is useful to consider some of the basic concepts introduced earlier by Ferdinand de Saussure, father of the current known as linguistic structuralism. 1.3. Language as a system of signs The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), one of the most influential linguists in the development of modern linguistics, defined human languages as a system of signs. The linguistic sign has two components: signifier and signified. The signifier is a sequence of sounds. The meaning is the concept. For example, to express the concept of a tree, in Spanish, we use the sequence of sounds /-r-b-o-1/. It is important to note that the relationship between signifier and signified is essentially arbitrary. There's no reason why the sequence of sounds /-r-b-o-l/ is more appropriate than any other to express the concept. We see this clearly when comparing different languages. In Spanish, we say tree in English is the tree, and in Basque zuhaitz. The opposite of arbitrary is motivated. Let's consider for a moment another system that we use in communication, that of traffic or traffic lights and signals. Some of these signals are motivated and others are arbitrary. A drawing of children holding hands, to indicate that there is a school and you have to pay attention to the passage of children, is a motivated sign. There is a natural relationship between the signifier (the traffic sign) and the meaning it expresses. The same can be said of a sign with a picture of a cow to indicate that there may be cows crossing the road. There is a reasoned or logical relationship between the design of the sign and what it means. On the other hand, a round red mark with a white stripe in the middle does not suggest anything to us as to its meaning. Here is a purely arbitrary relationship. The relationship between traffic light lights and their meaning is also arbitrary. The reason these arbitrary sign systems work despite their arbitrariness is because there is a convention that all members of society have to learn. The society we live in might have decided that a red light means go instead of stop. The important thing is that we all obey the same convention. What is clear is that if each of us could interpret traffic lights and other arbitrary signals in their own way, this would result in total chaos and the collapse of traffic. The same is true of human languages. I, as an individual, cannot decide that to express the concept of "tree" I am going to say / brla/. If we did this, languages would not serve to communicate. As children (or when we learn a foreign language as adults) we learn the conventions, and the arbitrary relationships between signifiers and signifieds that are used in our community of speakers. We have just said that among the signs of circulation, some show a motivated relationship between the design and the concept they express. In human languages, there are very few motivated signs. In onomatopoeia, we find a motivated relationship, but even here there is usually an element of arbitrariness and conventionalization: in English dogs bow-wow, and in Spanish woof-woof. We will return to this topic in section 2.2 of this chapter. Cognitive science is the study of human intelligence in all its manifestations and facets, from the study of perception and action to the study of reasoning and language. Under this rubric fall both the ability to recognize a friend's voice on the phone and reading a novel, jumping from stone to stone to cross a stream, explaining an idea to a classmate, or remembering the way back to home. The cognitive perspective in the study of language assumes that language is a cognitive system that is part of the mental or psychological structure of the human being. Faced with the social perspective of language, which studies, for example, the relationship between the social structure and the different varieties or dialects of a given language, the cognitive perspective proposes a change of perspective from the study of linguistic behavior and its products (the written texts, for example), to the internal mechanisms that enter into human thought and behavior. The cognitive perspective assumes that linguistic behavior (texts, speech manifestations) should not be the authentic object of study of our discipline, but that they are nothing more than a set of data that can provide evidence about the internal mechanisms of the mind and the different methods in which these mechanisms operate when executing actions or interpreting our experience. One of the basic ideas in the Chomskyan model of the study of language that has been the greatest cause of controversy since the sixties is precisely this, that the objective of our discipline should be the tacit knowledge of the language that the speaker possesses and that underlies his language. use, rather than the mere study of such use. This is a methodological approach that goes against the ideas of previous models of language study, both modern and traditional. For Chomsky, grammar should be a theory of competence, that is, of the tacit knowledge that the speaker has of his own language and that allows him to encrypt and decipher statements or messages, more than a model of performance, the specific use that the speaker makes his competence. Knowledge of the language and the ability to use it are two entirely different things according to his theory. Two people may have the same knowledge of the language, the meaning of words, their pronunciation or sentence structure, etc., but they may differ in their ability to use it. One may be an eloquent poet and the other a person who uses the language colloquially. Similarly, we can temporarily lose our ability to speak due to injury or accident and later regain speech. We must think in this case that we have temporarily lost the ability but we have kept our knowledge of the language intact, which has allowed us to later recover its use. The cognitive model is, since it affirms that language has its reality in the human brain, a mentalist model: it is interested in the operations of the mind that lead us to produce and interpret linguistic statements. We can summarize the basic questions about language that the cognitive model attempts to answer in four: (i) What is the nature of the cognitive system that we identify as knowing our own language? (ii) How is such a system acquired? (iii) How do we use such a system in the comprehension and production of language? (iv) How and where is this system located in our brain? In the next sections, we are going to review the answers that the cognitive model in the study of language offers to these questions. 2.1. The nature of language: competence and performance The Chomskyan concepts of competence and performance have a certain relationship with the dichotomy between language and speech established by Ferdinand de Saussure. Saussure, of whom we have already spoken, established a distinction between the language (in French langue) and speech (in French parole). Language is the system of signs that is used in a community of speakers. Thus Spanish, French, and Quechua are examples of different languages. We linguists can investigate and describe languages by analyzing speech acts; that is, observing the use of the language by the speakers. Speech is, then, the concrete use of language. A third concept that Saussure uses is that of language (in the French language), which would be the ability that human beings have to learn and use one or more languages. Chomsky identifies our knowledge of language or competence with the possession of a mental representation of grammar. This grammar constitutes the competence of the native speaker of that language. In other words, grammar is a speaker's linguistic knowledge as it is represented in his brain. A grammar, understood in this in this sense, it includes everything one knows about the structure of their language: its lexicon or mental vocabulary, its phonetics and phonology, the sounds and the organization of these in a systematic way, its morphology, the structure and the rules of formation of the words, their syntax, the structure of sentences and the restrictions on their correct formation, and their semantics, that is, the rules that govern and explain the meaning of words and sentences. But we must note that this knowledge that the speaker has of his own language is not explicit knowledge. Most of us are unaware of the complexity of such knowledge because the linguistic system is acquired unconsciously, in the same way, that we learn the mechanisms that allow us to walk or kick a soccer ball. The normal use of language therefore presupposes mastery of a complex system that is not directly accessible consciously. From this point of view, understanding our knowledge of a language is understanding how that mental grammar works and how it is structured. Linguistic theory is concerned with revealing the nature of the mental grammar that represents a native speaker's knowledge of his own language. This knowledge is not easily accessible to study, since most speakers are not capable of explicitly articulating the rules of their own language, of explaining, for example, why we say I'm sorry to bother you but not Sorry to bother you, whereas we can say both I don't want to bother you and I don't want to bother you. The cognitive linguist must therefore approach the properties of this tacit knowledge system indirectly. The methods that linguists use to infer the systematic properties of language are varied. Some study the properties of language change by comparing different stages in the development of a language in order to deduce what systematic properties might explain historical changes. Others analyze the properties of language in patients with certain pathologies and try to find the properties that could explain irregular language use due to injury or trauma. We can also study the properties common to all human languages to deduce the rules that allow us to explain their common features. Frequently, especially within the Chomskyan school, attempts are made to find out the regular properties of language by formulating hypotheses and evaluating their predictions based on the speaker's intuitive judgments about the grammaticality of sentences. This methodology consists of asking the native speaker questions such as: Is sentence X acceptable in your language? Given two apparently related sentences, do they both have the same interpretation? Is sentence X ambiguous, that is, can we interpret it in more than one way? In sentence X, can word A and word B refer to the same entity? Let's pay attention to a concrete example. In the sentence The teacher thinks he is smart, can "the teacher" and "he" refer to the same person? It is unquestionable for a native Spanish speaker that the answer is affirmative, although it is not the only possible interpretation of the sentence, since "he" and "el profesor" can refer to two different people as well. And in the sentence, does he think the teacher is smart? The answer, in this case, is surprisingly different, although we have only changed the order of the sentence elements: now it is only possible to interpret the sentence so that the two segments refer to two different people. With data of this type, the linguist tries to formulate hypotheses about the properties of the speaker's internal knowledge system that could explain these judgments about the coreferentiality of two elements in the same sentence, about the possibility that both have the same referent. He might propose, for example, that it is impossible for a pronoun like "he" to be co-referential with an expression that does not precede it in discourse. This hypothesis automatically establishes a series of predictions about the behavior of pronouns in a certain language that must be contrasted with new data, derived from questions similar to the previous ones. We can ask ourselves not only if this behavior can be generalized to all sentences of a language in which pronouns like "he" and referential expressions like "the teacher" appear, but also if this is a specific feature of the language we are studying or a feature common to all languages. Two important characteristics of this type of research should be noted. First, that if the linguist is a native speaker of the language being studied, the linguist himself performs, in many cases, the simultaneous functions of informant and researcher, using his own judgments as research data. These introspective data reflect one of the idealizations of the Chomskyan model, which assumes the existence of the ideal speaker-listener. who lives in a perfectly homogeneous speech community, who masters its language perfectly, who is not affected by "irrelevant grammatical conditions". " such as loss of memory or attention, which does not produce errors in the use of its linguistic competence and whose judgments of grammaticality are to be the basis for our description of grammar. But in many cases, it is the linguist himself who is the informant, the ideal speaker-hearer that is closest at hand. The validity and objectivity of this type of analysis have frequently been questioned and its use has been the subject of constant discussion among linguists. Many of them think that other, more reliable analytical tools, and more rigorous quantitative and qualitative experimental methods, should take the place of data derived from mere introspection. And they also believe that the idealization of an ideal speaker who does not make mistakes, although directly linked to the proposal that the objective of the study of our discipline is the competence and not the performance, it constitutes a non-intuitive idealization that goes against the observable facts. Second, we must point out that the linguist, in trying to describe the regularities of a native speaker's language system, is really trying to construct a theory of a system that is not directly observable on the basis of observable data; in this case, the judgments of a native speaker. The distinction between theories and data is of crucial importance in any type of systematic or scientific study. Many authors doubt the validity of data derived solely and exclusively from the grammaticality judgments of native speakers. In addition to proposing that the study of language must be fundamentally mentalist, that is, that its object of study must be the unconscious psychological system that allows us to produce and interpret sentences in our native language, Chomsky proposes that the human mind is modular, that is, it possesses "mental organs" designed to perform certain tasks in specific ways. There is a specific module in our brain, a "linguistic mental organ" uniquely designated to perform linguistic tasks. This "language organ" is a fascinating object of study because it is unique among animal species and characteristic of the human species. All human beings possess a language and, according to Chomsky's theory, no other animal species is capable of learning a language. Thus, by studying the structure of human languages we are investigating a central aspect of our nature, a distinctive feature of our species. If we agree with this way of reasoning, linguistics is, to a certain extent, part of psychology, since it studies language as a window into the functioning of thought, and part of biology, since it studies language as a characteristic feature of an animal species, the human species. The linguist Steven Pinker explains very clearly why, then, cognitive linguistics is descriptive and not prescriptive: Suppose that we are biologists interested in shooting a documentary for an educational television channel in our country and that our objective is to study the song of the whales, a complex and exclusive method of communication of that animal species. Probably one of the most irrelevant statements that we could propose would be: "This whale does not sing correctly." Or, in the same way, "the whales of the North Pacific sing worse than those of the South Pacific." Or "the whales of this generation do not sing as well as the whales of past generations". In the same way, it does not make much sense to say that "this person does not know how to speak correctly", that "the speech of Valladolid is more correct than the speaks of Tijuana" or that "young people don't speak Spanish as well as their grandparents. Modern linguistics is, by the nature of its proposals, fundamentally descriptive. 2.2. Animal communication: characteristics of human language The faculty of language is characteristic of the human species, and our ability to develop the grammar of a language is unique among animal species. For centuries it has been thought that only humans are capable of rational thought-only humans have a soul because only humans have language, as Descartes claimed. But there is no doubt that communication exists in all animal species, understanding by communication any action on the part of an organism that can alter the behavior of another organism. It is also evident that many animal species have their own communication systems, and even that these communication systems are, in certain aspects, similar to human language. We know that whales have one of the most complex signal systems that exist on our planet, that certain apes have the ability to transmit distress calls of varied content and of a certain complexity, that dolphins communicate with each other or that bees, To cite a final example, they can transmit information about the distance and orientation with respect to the sun of the food source, as well as its richness. Can we, therefore, affirm that only the human species possesses the faculty of language? Is human language special, different from other communication systems? The origin of the confusion seems to be in the more or less restricted use of the term "language". What is a language? Is the communication system of bees a language? And the ape-calling system? Is mathematics a language? What can we say about attempts to teach chimpanzees or dolphins a human language? Although the answer that modern linguistics claims to give is that the differences between natural languages and animal communication systems are qualitative and not just variations of degree, the important thing to remember is that the comparison between animal communication systems and human languages tells us can say something important about human language. In particular, they can serve as evidence to affirm or deny the idea that in order to have a human language one must be biologically specialized for it, that language is not only the natural result of obtaining a certain degree of intelligence in the process of evolution of the species. The first step in this line of reasoning is then to examine the similarities and differences between animal communication systems and human communication in order to isolate the specific features of the language. Second, we will briefly examine attempts to teach certain animal species some form of human communication to prove or refute the proposition that no animal can acquire a natural language. The specific characteristics of human language (of all human languages), not shared by other communication systems, can be summarized as follows: (i) Arbitrariness. When there is no direct relationship or dependency between the elements of a communication system and the reality to which they refer, they are said to be arbitrary. The signs of the language are mostly arbitrary. There is nothing in the word horse that behaves, looks, or neighs like a horse, in the same way, that there is no relationship between the words horse or cheval and the four-legged animal, although both mean "horse", in English and French respectively. If there is motivation or a direct relationship between the signal/sign and the referent, the communication is said to be iconic. In all linguistic systems, there is a percentage of iconicity, although this constitutes a minor part of the language. Onomatopoeia, for example, is essentially iconic, although to a lesser degree than we might expect at first glance. We see that onomatopoeias are not totally iconic in the fact that they vary from language to language: English speakers say that roosters say cock-a-doodle-doo while those of Spanish know perfectly well that what they say is kokorik in some dialects and kakariki in others. The frequency in the movement of the bee dance is iconic since it is directly proportional to the distance from the food source. The alert calls among certain primates, which allow differentiating the type of danger depending on the animal that threatens them, are, on the other hand, arbitrary, since there is no relationship between the sounds produced to express an alert and the predators that cause them. (ii) Displacement. We speak of displacement when the signals or signs can refer to distant events in time or space with respect to the situation of the speaker. Most of the calls and signals in the world of animal communication reflect the stimulus of their immediate environment and cannot refer to anything in the future, in the past, or to any place other than the one shared between sender and receiver. It would be hard to think that our dog could communicate the idea "I want to go for a walk tomorrow at three in Istanbul." Or, using the example of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, that an ape could express the idea "my father was poor but honest." One of the predominant features of animal communication is that it does not present displacement. (iii) Dual articulation. The sounds of a language have no intrinsic meaning but combine with each other in different ways to form elements (words, for example) that have meaning. As we will see in more detail in chapter 2 , in a statement like / megstaelpn/ we can distinguish a series of elements with signifier and meaning, among them the word /pn/. At another level of analysis, we can distinguish a series of sounds that we use in Spanish, which we call phonemes. In /pn/ we have three phonemes. What no longer makes sense is to ask what the phoneme/p/ means. A communication system that is organized according to two levels, one in which the minimum elements lack meaning and another in which these units are grouped to form significant units, is a dual system. Every human language has this property. Duality in the strict sense allows the combination of words in an unlimited way, and this constitutes a procedure that allows great simplicity and economic characteristics of linguistic systems. Sounds are organized into syllables and form words. These are articulated or combined in phrases and sentences, and these are combined with each other to form texts, speeches, etc. Signs in animal communication systems, on the other hand, are rarely combined with each other to form new symbols. (iv) Productivity. There is an infinite capacity in human languages to understand and express different meanings, using known elements to produce new elements. The language system allows us to form an infinite number of sentences. Animal communication systems present, on the contrary, a finite and delimited number of possible statements. (v) Prevarication. It consists of the possibility of issuing messages that are not true, in the possibility of lying. In general, none of the animal communication systems possesses this property, although in recent years it has been shown that some apes are capable of producing the alarm signal signifying the approaching presence of a predator, to ensure that other apes stay away. of food, which constitutes a clear example of prevarication. That is, there are apes that lie as if they were humans. (vi) Reflexivity. When a communication system allows referring to itself, we say that the system is reflexive. The linguist Roman Jakobson affirmed that one of the functions of language is precisely this, the metalinguistic or reflexive function. With language we can produce statements that have language as an object: "a" is an indefinite article. Animal communication systems do not possess this property. (vii) Discrete units. Languages use a reduced set of elements (sounds) that clearly contrast with each other. When the units of a communication system are clearly separable into different elements, we say that the system is discrete or that its signals are discrete or digital. The sounds of the language are perceptible by the listener as differentiating units. In animal communication systems, signals (grunts, for example) tend to be analog signals, that is, they are presented on continuous scales of variable intensity, such that the length, tone, or intensity of the signal can vary with time. degree of emotion or informational content that is intended to be expressed. But a "book" is not a bigger or heavier object than a "book" in any natural language. (viii) Creativity. The use of human language is not conditioned by external or internal stimuli in the production of a statement. Utterances are unpredictable under normal conditions, while animal communication tends to be much more rigidly controlled by external stimuli than human behavior. Except in irrelevant cases, such as expressions such as Good morning, My house is your house, etc., we do not limit ourselves to repeating phrases that we have already heard, but we have the ability to create new phrases appropriate to the changing needs of each moment. And conversely, we understand sentences that others produce despite never having read or heard them before. These features-arbitrariness, displacement, dual articulation. productivity, prevarication, reflexivity, use of discrete units, and creativity-are shared by all human languages, define a human language, and differentiate it from animal communication systems. We can thus defend the idea that language, characterized by these features, is unique in the animal world and characteristic of our species. But cognitive linguistics also defends the idea that no non-human animal is capable of acquiring a language that presents these features. Attempts have been made to teach communication systems similar to human language to other species: dolphins, parrots, pigeons, parakeets, or sea lions. Undoubtedly, the most interesting attempts are those whose object is to teach language to apes, and especially to chimpanzees, since these are undoubtedly our closest relatives in the animal world and the genetic distance between them and humans is very small (we must take into account that our genes are identical to those of chimpanzees in a percentage greater than 95 percent). The first attempts to teach chimpanzees to use a language were frustrated by an insurmountable limitation: the ape's vocal apparatus is not designed to produce the sounds of speech. From initial experiments with Viki, a chimpanzee who learned to pronounce four words in English in the 1940s, the researchers realized that given chimpanzees' physiological limitations in vocalizing, there would be a greater chance that could learn manual sign language. Human languages are not limited to oral modalities, but there are also systems of manual signs, used in deaf communities. Sign languages are full human languages, simple gestural modalities of our linguistic capacity that thought and that, since the Chomskyan proposal in the early sixties that human beings possess an innate knowledge of natural languages, has intensified. the interest of philosophers and psychologists on issues related to learning and the acquisition of knowledge. The fact that part of what we know about our language is innate may seem to be a reasonable hypothesis to a greater or lesser extent. But it is worth asking what kind of empirical evidence supports this hypothesis. Cognitive linguistics finds data to favor this idea in the following arguments: (i) The universality of language The fact that all human groups have a language is not sufficient evidence by itself to affirm that language is innate since many things are universal but not innate (liking certain soft drinks or television, for example, are universal but we should not claim that television is part of our genetic code, although there sometimes seems to be evidence in favor of this proposal). For the linguists of the Chomskyan school, what is crucial is not only that all cultures have a language, but that the apparently great differences between languages are not such. They propose that at a given level of description and abstraction, languages have many more similar features than differentiating features; In this sense, language presents universal characteristics. Not only the fact that all languages have subjects and predicates, for example, but even more curious phenomena such as the relationship between the position of pronouns and the interpretation of the antecedent to which they refer seem to be common in all languages, or that the question formation mechanisms are shared by all known languages. For example, there are no languages in which, starting from the sentence I play the guitar and the piano, we can formulate the question *What do you play and the piano?, although the question is impeccably logical, without resorting to circumlocutions such asWhat instrument Do you play besides the piano? If we agree that the various languages of the world have many things in common, the argument for the universality of language is reasonable. If we assume that these common features are innate, we can explain why they are common to different languages. It must also be considered that languages have changed and evolved over thousands of years. If there were no innate limits to what constitutes a human language, we could not explain why languages have not developed into completely different systems, similar only in the sense that they serve to communicate. (ii) The argument of the poverty of stimuli This is one of the crucial arguments in the Chomskyan model and, in general, in the models that assume that part of our knowledge is innate. Said argument is based on the enormous gap between the information about the external world that is accessible to our senses and the complex knowledge that we acquire about it. What we know is much more complex than what we can deduce from the mere data of experience. In the case of the acquisition of linguistic knowledge, the argument is related to the fragmentary data that the child receives from his mother tongue and the distance between this data, and the complexity of the linguistic system that the child acquires in an astonishingly short period of time. According to the Chomskyan school, the linguistic data that surrounds us is so fragmentary and incomplete that it should make learning a language impossible. Obviously, context and experience play a crucial role in the acquisition, but it is inconceivable to leave out the participation of heredity and nature. To give a very simple example: how are the meanings of words acquired? Suppose someone points in a certain direction and pronounces the word door or any other word that the child hears for the first time. How does the child know that the word door refers to the physical object we are trying to describe, and not to its frame, or to the handle, or to a specific section of it, or to its color, to any object that has a rectangular shape, to a fragment formed by the door and the wall? How does it know that what we are describing is not an action but an object? We can look for different explanations for this simplified example, and we could probably assume that there are all sorts of contextual clues, both grammatical and extra grammatical, of repeated information or clues in our attitude or behavior that help the child determine the meaning of the word. But the explanations we provide will undoubtedly be undermined if we think that children learn vocabulary at an astonishing rate, between nine and ten new words a day. In fact, we know very little in detail about how children acquire the meanings of words, or how they acquire the grammatical structures of their language. The question is fascinating, no doubt. Numerous studies have shown that grammatical development does not depend on explicit language instruction and that children do not learn the language because we are continually explaining to them which sentences are grammatical and which are not. We might think that if parents or other adults corrected the children's grammar, this information could help in the acquisition process. But parents are not generally concerned with the grammaticality or correctness of their children's utterances-as hundreds of hours of recording of parent-child exchanges have shown-they are more concerned with whether what children say is true or not fake or that they behave well. There are arguments to support the idea that not only do we not learn through explicit instruction, but we also do not learn by imitating the language of our parents or by analogy or at least, since both imitation and analogy are processes that are obviously part of the acquisition mechanisms, that there are numerous areas of our knowledge of the language that cannot be explained in this way. First, if we learned solely by imitation, we could not explain certain mistakes that children make but are not made by the people around them. Generalizations in the processes of word formation are a good example: children tend to say I am instead of I was, or I will go out instead of I will go out. In doing this, the child applies by analogy, and with a lot of logic and common sense, productive rules of word formation, ignoring that the verb forms present irregularities that he will learn little by little. What is interesting, in addition to the impeccable logic of children, is that no matter how much we correct this type of error, the child will continue to commit it until a certain age, the age at which language irregularities are learned uniformly. Imitation of the parents' speech is not enough to acquire the language in its entirety. The same example above raises the problem of learning by analogy. It is clear that generalizations of word formation rules can be learned by analogy with the regular rules of the language. But there are constructions that cannot be learned by analogy. The classic example is the following: suppose that the formation of total interrogative sentences is produced by means of the preposition of the auxiliary verb; that is, we form the question Is Juan intelligent? from the sentence John is clever, placing the first verb at the beginning of the sentence. This mechanism should be easy to observe and to acquire by analogy, a reasonable proposition. But if we were to learn by analogy, we would expect that from the sentence The child next to me is intelligent, the child would form the question Is the child next to me intelligent, a mistake that a child never makes. The necessary knowledge to form the correct question Is the child next to me intelligent? it is quite complex, as we will see in chapter 4 (on syntax), and it is not easily explained by analogy with other examples nor is it the product of explicit instruction. The explanation offered by Chomskyan linguistics for language learning, is if it does not occur as a result of explicit instruction, by imitation of our parents or the people in charge of caring for us or educating us, or through general mechanisms of learning, such as generalizations by analogy, is the following: an independent cognitive module specialized in language acquisition exists in our mind or brain. The initial state of this module is formed by the principles common to all languages that refer to both sounds and meanings or the construction of words and sentences that are present in our minds thanks to genetic inheritance. This module begins a maturation process when exposed to relevant linguistic data through experience and observation of the language that surrounds us. The final result of this maturation process is a state different from the initial one and which corresponds to the grammar of a particular language: Spanish, English, Basque, etc. -according to the language to which the child has been exposed. (iii) Creole languages We call pidgin language the language developed in verbal communication between speakers who do not share a common language. These languages arise, in general, when two or more people come into contact in a situation of exchange or trade. If these people do not share a common language, they develop a simplified language to facilitate exchange and communication. A couple of examples are Chinook Jargon, used by Native Americans and French and British traders to communicate with each other on the Pacific Northwest coast of America in the 19th century, and the 17th-century lcelandic Basque pidgin of which we have samples such as for ju mala Girona "you are a bad man" and for mi presents for ju bustana "I will give you the tail (of the whale)". Similar examples are found in situations of contact between missionaries or traders and native populations in other parts of the world. These languages are characterized by having a very limited set of words and very simple grammatical rules, so communication depends mostly on the information provided by the specific context of the communication to disambiguate the possible meanings or the use of metaphors and complex circumlocutions. In general, in all these languages it is impossible to express morphologically the grammatical function of words and the case (subject, object, etc.), temporal differences (present, past, or future), and aspect differences (completed or incomplete action). ) or mood (subjunctive or indicative). Pidgins lack prepositions or have a very small number of them. One of its crucial features is that there are no native speakers of a pidgin language. Now, when a pidgin is adopted by a community of speakers, the children of that community can acquire it as a native language. We say that this language has then become a creole language, that it has been creolized. Creole languages become, in a single generation, fully developed languages that present an extensive vocabulary and complexity in their structures identical to that of any other human language. Somehow, in a very short space of time, children who are exposed to a language pidgin as a mother tongue automatically endow it with structural complexity, with grammar, and consolidate it in a creole language. Linguist Derek Bickerton suggests that the study of pidgin languages and creole languages may provide relevant data for the implications of our theories about language. Two of the features of these languages pose interesting problems when analyzing the mechanisms of language acquisition and learning. First, the emergence of a creole language from a pidgin language assumes that speakers are able to add to it grammatical features that were not historically present in the original pidgin language. Creolization, even to a greater degree than normal language acquisition, presupposes that learning without explicit instruction is possible. Second, according to Bickerton and some other linguists, many of the world's creole languages display similar features (all differentiate, for example, the presence and absence of direct objects through grammatical agreement mechanisms, and all tend to display the same order of sentence elements). For Bickerton, there is only one hypothesis that can explain these data: the existence of an innate "bioprogram" for language that specifies a set of specific grammatical structures to which the child has access in the event that the data of the language to which that is exposed are incomplete or unstable, evidence that part of our language faculty is innate (iv) The stages in language acquisition Although we postulate that language is innate, children are not born speaking. Knowledge of their language develops in very defined periods or stages, so that each stage is successively closer to the grammar of the adult language. When observing the stages of development in different languages, it has been noted that the stages in the acquisition of the language by the child are very similar, and in the opinion of some linguists, universal. These stages are normally divided into pre-linguistic periods and linguistic periods. The first noises, purrs, or screams are nothing more than responses to environmental stimuli, hunger, discomfort, etc., and we can doubt their exclusively linguistic character. Around six or seven months of age, children begin to babble and produce reduplicative sounds like baba baba or dada dada. Many of the sounds that children produce at this stage are not characteristic sounds of their parent's language, but at ten months of age, they use only the sounds of their mother tongue and do not distinguish between sounds and phonemes of languages other than their own. At the end of the first year, children learn to change the content of syllables, which are no longer necessarily reduplicative (da-di, ne-ni). The language learning mechanisms are already in operation. Children produce their first single words at ten to eleven months, although they understand certain words months before reaching this point. The most frequent kinds of words that a child produces at this age are names of specific individuals (dad), objects (table), or substances (water). These words appear uniformly in all languages and cultures. From there the children acquire some verbs (to give) and adjectives (big). First words tend to reflect objects that stand out in their environment and do not include words that name objects or abstract actions. Around eighteen months of age, there is an explosion in the number of words a child uses and understands. This explosion is accompanied by the appearance of combinations of two words (gives water or big car), a first sign of productivity and creativity in the use of language. There is a correlation in all languages between the increase in the number of words and the appearance of rudimentary sentences made up of two elements. The sentences that the child produces resemble telegrams in which the prepositions and concordance morphemes have been left out (a, de, la, -s for the plural or -aba to express the past). However, even at this early stage, children make very few word order errors (they do not say, for example, big car or water gives). When these words of grammatical content appear, they tend to appear in a certain order (in English, the gerunds in -ing before the third person inflection, for example). Around two and a half years of age, the telegraphic stage ends abruptly and sentences of variable length begin to appear, while words of grammatical content appear uniformly in their speech, most of the prepositions that are missing in the previous stage. , For example. The structures used by the child become more and more complex: interrogative sentences (Are you hungry?), relative clauses (The car I like), and certain types of subordinate clauses (I want to eat) appear. In this period, erroneous generalizations of word formation processes are frequent (I walked instead of walked, I did instead of I did). Vocabulary grows at a rapid rate, with an average of nine words a day between eighteen months and six years of age. Any normal child who is part of a language community acquires at least one language at an early age. After puberty, the development of their linguistic knowledge has reached a stable level that does not differ broadly from the level achieved by other children of the same age in the same community. In this sense, the development of language presents the same characteristics as all animal behavior that is biologically conditioned, as Eric Lenneberg first pointed out, since both one and the other develop following clearly differentiated stages and that they also present a "critical period" for the acquisition of said behavior. Thus visual neurons in cats develop and adjust to perceive horizontal, vertical, and oblique lines only if they are exposed to them before reaching a certain age. The same happens with the instinct of some birds to follow their mother or with the ability of some birds, such as canaries, to learn to whistle like their parents. Are there critical periods in language learning? If the acquisition of language not only develops in well-differentiated and independent stages of the language in question, and if the acquisition presents a critical period for learning, we have relevant data to deduce by analogy that language is biologically conditioned just as it is there are certain animal instincts. 2.4. Language and the brain: neurolinguistics The Neurolinguistics is the study of the brain structures that a person must have in order to process and understand a language. The basic question that neurolinguistics tries to answer is this: how is language represented in the brain? Research on both human and animal brains, psychologically or anatomically, has helped answer some of the questions about the neurological foundations of language. We know that there are specific areas of the brain that seem to be specialized for it. Under the innate hypothesis this is not the result of coincidence or accident: the brain, like the rest of the body, develops according to a genetic blueprint that partly determines how we process language. When it comes to studying language, and until recent years, when there has been an increasing and spectacular development in techniques for studying the brain, neurolinguistics has had to settle for indirect methods such as the study of speech disorders. language suffered by certain patients with brain injuries. These methods are indirect because there are ethical considerations that prevent us from opening the skull of a living

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts