Question

Draw a simple diagram/map of how customer demand information flows upstream from the retailers to Barillas production. What do you think are the main causes

Draw a simple diagram/map of how customer demand information flows upstream from the retailers to Barilla’s production. What do you think are the main causes of the large fluctuations in orders observed at the Pedrignano CDC? How can Barilla cope with the increase in demand variability? Discuss what other information should flow properly within the supply chain to match supply and demand.

Barilla Case Study

Company Background

Founded in 1875 by Pietro Barilla in Parma, Italy, as a small shop with an attached "laboratory" for pasta and bread production, the company went through significant growth under Ricardo, Pietro's son. In the 1940s, Pietro and Gianni Barilla took the reins. Over time, Barilla expanded into a large, vertically integrated corporation with various facilities across Italy.

To stand out in a crowded market of over 2,000 Italian pasta manufacturers, the Barilla brothers focused on delivering a high-quality product with innovative marketing. In 1968, they invested in a cutting-edge pasta plant in Pedrignano to support their double-digit sales growth from the 1960s. This facility, while impressive, drove them deep into debt, but they recovered through capital investments, organizational changes, and improved market conditions.

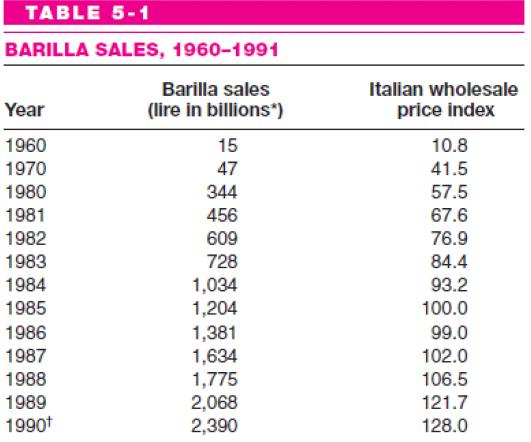

Table 5.1 illustrates Barilla's remarkable growth during the 1980s, with an annual growth rate exceeding 21%. This expansion was achieved by growing existing businesses in Italy and other European countries and acquiring related businesses.

By 1990, Barilla became the largest global pasta manufacturer, commanding a 35% share of the Italian pasta market and a 22% share in Europe. The company operated under three pasta brands in Italy and held a significant share of the bakery-products market. It was organized into seven divisions, with its corporate headquarters adjacent to the Pedrignano pasta plant.

INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

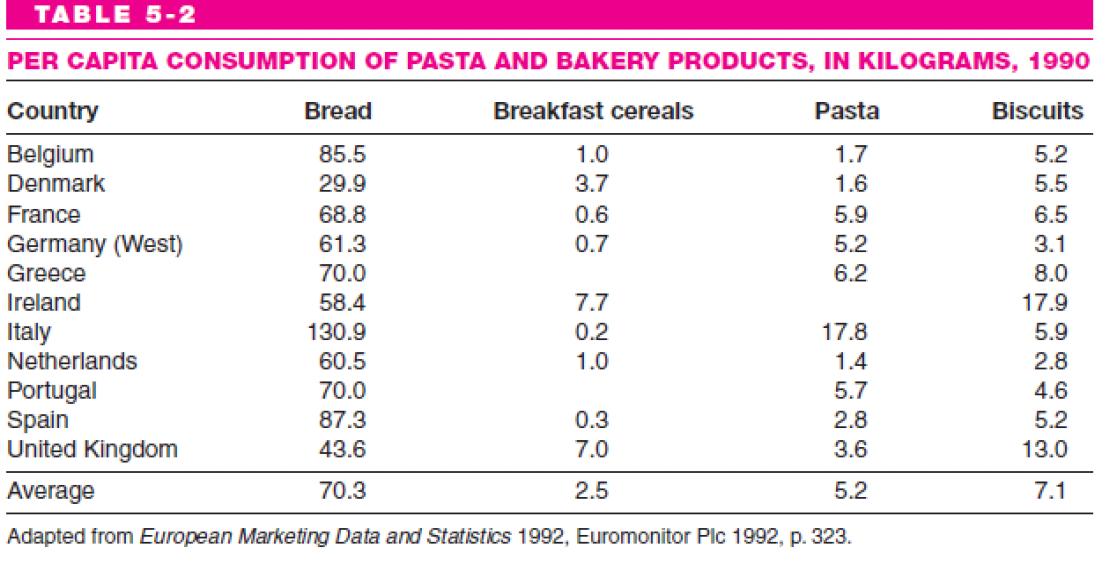

The origins of pasta are unknown. Some believe it originated in China and was first brought to Italy by Marco Polo in the 13th century. Others claim that pasta’s origins were rooted in Italy, citing as proof a bas relief on a third-century tomb located near Rome that depicts a pasta roller and cutter. “Regardless of its origins,” Barilla marketing literature pronounced, “since time immemorial, Italians have adored pasta.” Per capita pasta consumption in Italy averaged nearly 18 kilos per year, greatly exceeding that of other western European countries (see Table 5-2). There was limited seasonality in pasta demand—for example, special pasta types were used for pasta salads in the summer while egg pasta and lasagna were very popular for Easter meals. In the late 1980s the Italian pasta market as a whole was relatively flat, growing less than 1 per-cent per year. By 1990 the Italian pasta market was estimated at 3.5 trillion lire. Semolina pasta and fresh pasta were the only growth segments of the Italian pasta market. In contrast, the export market was experiencing record growth; pasta exports from Italy to other European countries were expected to rise as much as 20 to 25 percent per year in the early 1990s. Barilla’s management estimated that two-thirds of this increase would be attributed to the new flow of exported pasta to east-ern European countries seeking low-priced basic food products. Barilla managers viewed the eastern European market as an excellent export opportunity, with the potential to encompass a full range of pasta products.

PRODUCTION/PLANT NETWORK

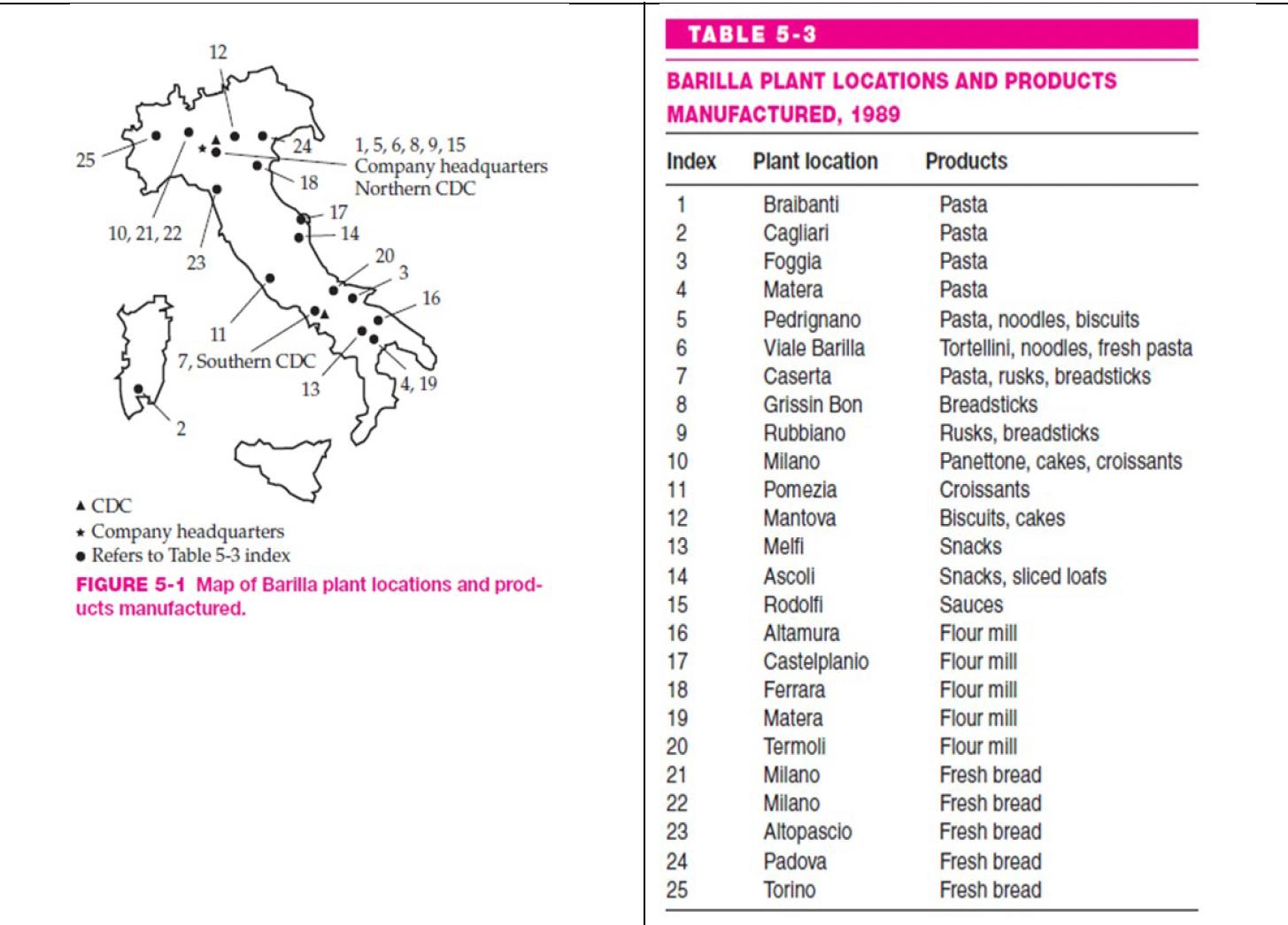

Barilla operated an extensive plant network in Italy (see Table 5-3 and Figure 5-1), including flour mills, pasta plants, and fresh bread facilities, along with plants producing specialty items like panettone (Christmas cake) and croissants. The company also had advanced research and development (R&D) facilities in Pedrignano for testing new products and production processes.

Pasta production at Barilla was akin to paper manufacturing. They mixed flour, water, and sometimes eggs or spinach meal to create dough, which was then rolled into thin sheets through a series of rollers. The dough passed through bronze extruding dies to shape the pasta. After cutting, the pasta was dried in temperature and humidity-controlled kilns. Following this four-hour drying process, the pasta was weighed and packaged.

Barilla utilized fully automated 120-meter-long production lines in its Pedrignano plant, where 11 lines produced 9,000 quintals (900,000 kilos) of pasta daily. The company specialized its pasta plants based on the type of pasta produced, including distinctions in composition and whether the pasta was dry or fresh.

For non-egg pasta, Barilla used high-quality grano duro (hard wheat) flour, while more delicate products like egg pasta and bakery items were made with flours from grano tenero (tender wheat). Barilla's flour mills processed both types of wheat. Even within the same pasta category, individual products were assigned to plants based on their size and shape, with "short" and "long" pasta produced separately due to equipment differences. (see Table 5-3 and Figure 5-1).

CHANNELS OF DISTRIBUTION

Barilla categorized its product line into two groups:

- "Fresh" products, including fresh pasta (21-day shelf life) and fresh bread (1-day shelf life).

- "Dry" products, like dry pasta and longer-shelf-life bakery items, comprising approximately 75% of Barilla's sales. These products had either "long" shelf lives (18 to 24 months) or "medium" shelf lives (10 to 12 weeks), resulting in around 800 different packaged stockkeeping units (SKUs). Barilla offered pasta in 200 shapes and sizes, available in over 470 SKUs, often with various packaging options to suit customer preferences.

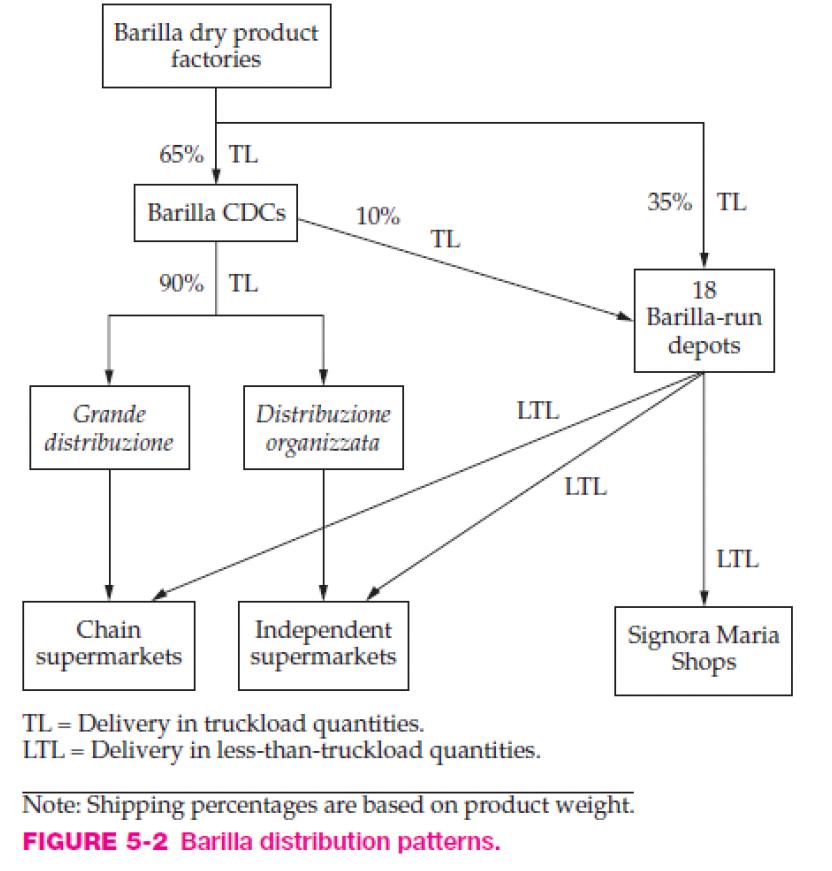

Most products were shipped to one of two central distribution centers (CDCs), the northern CDC in Pedrignano or the southern CDC near Naples. While fresh products skipped the CDCs, Barilla maintained separate distribution systems for fresh and dry products due to differences in perishability and retail service requirements. Independent agents purchased fresh products from the CDCs and distributed them through regional warehouses in Italy. For dry products, nearly two-thirds were destined for supermarkets and were bought by distributors at the CDCs for delivery to supermarkets. Brando Vitali's JITD proposal focused on these dry products sold through distributors. The remaining dry products were distributed through 18 Barilla-owned warehouses, primarily to small shops.

Barilla's products reached three types of retail outlets: small independent grocers, supermarket chains, and independent supermarkets, totaling around 100,000 retail outlets in Italy.

- Small independent shops: These were prevalent in Italy, with around 35% of Barilla's dry products distributed from the company's regional warehouses to these small shops. Typically, small shops held over two weeks of inventory at the store level, and purchases were made through brokers who dealt with Barilla.

- Supermarkets: The remaining dry products were distributed through external distributors, with 70% going to supermarket chains and 30% to independent supermarkets. Supermarkets usually carried 10 to 12 days of dry product inventory, with an average of about 4,800 dry product SKUs. Distribution to supermarket chains was managed by their own distribution organizations (grande distribuzione, or GD), while independent supermarkets used organized distributors (distribuzione organizzata, or DOs) as central buying organizations.

Distributors often specialized in a subset of Barilla's dry product SKUs based on regional preferences and retail requirements. These distributors typically carried 7,000 to 10,000 SKUs, with a two-week supply of Barilla dry products in inventory.

Many supermarkets placed daily orders with distributors, with store managers manually noting needed replenishments. Orders were then transmitted to the distributor, usually taking 24 to 48 hours for order fulfillment from the distribution center. (Refer to Table 5 and Figure 5-1 for further distribution network details.)

SALES, MARKETING, AND DEMAND PLANNING

Barilla's strong brand image in Italy was shaped by its marketing and sales strategy, which revolved around advertising and promotions.

Advertising: Barilla heavily advertised its pasta brands. Ad campaigns emphasized the premium quality and sophistication of Barilla pasta. One campaign featured the slogan "Barilla: a great collection of premium Italian pasta" and depicted uncooked pasta shapes like jewels against a black background, conveying luxury and elegance. Unlike competitors, Barilla chose modern, sophisticated settings in major Italian cities, avoiding traditional Italian folklore imagery.

Trade Promotions: Barilla's sales strategy focused on trade promotions to penetrate the grocery distribution network. Frequent promotions were essential due to Italy's traditional distribution system. Barilla divided the year into several "canvass" periods, each lasting four to five weeks and aligned with a specific promotional program. Distributors could purchase as much as needed during a canvass period. Sales representatives were incentivized based on meeting sales targets for each period. Discounts varied by product category, with typical discounts of 1.4% for semolina pasta, 4% for egg pasta, 4% for biscuits, 8% for sauces, and 10% for breadsticks. Volume discounts were also available, with incentives for full truckload orders. Additionally, sales reps might offer further discounts for larger quantities.

Sales Representatives: Barilla's sales representatives serving independent supermarkets (DOs) spent about 90% of their time working at the store level. They assisted with product placement, in-store promotions, monitored competitor activity, and discussed Barilla products and ordering strategies with store management. Regular weekly meetings with the distributor's buyer were held to assist with placing orders and addressing issues like returns and deletions. Sales reps used portable computers for order input. In contrast, a smaller sales force served supermarket chains (GDs), and orders were often transmitted to Barilla via fax, with fewer in-person interactions at GD warehouses.

DISTRIBUTION

Barilla's Distributor Ordering Procedures and the Impetus for the JITD Program:

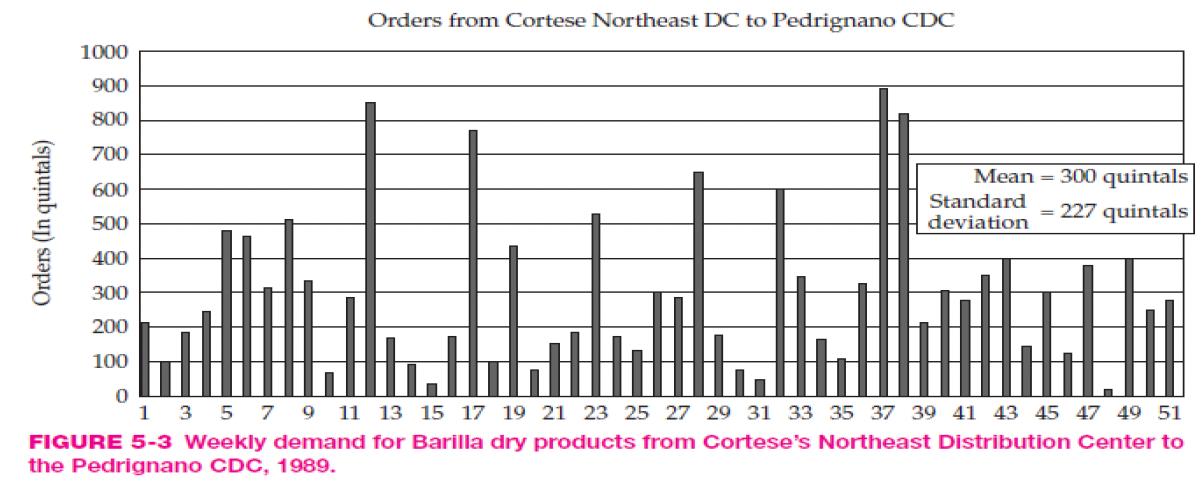

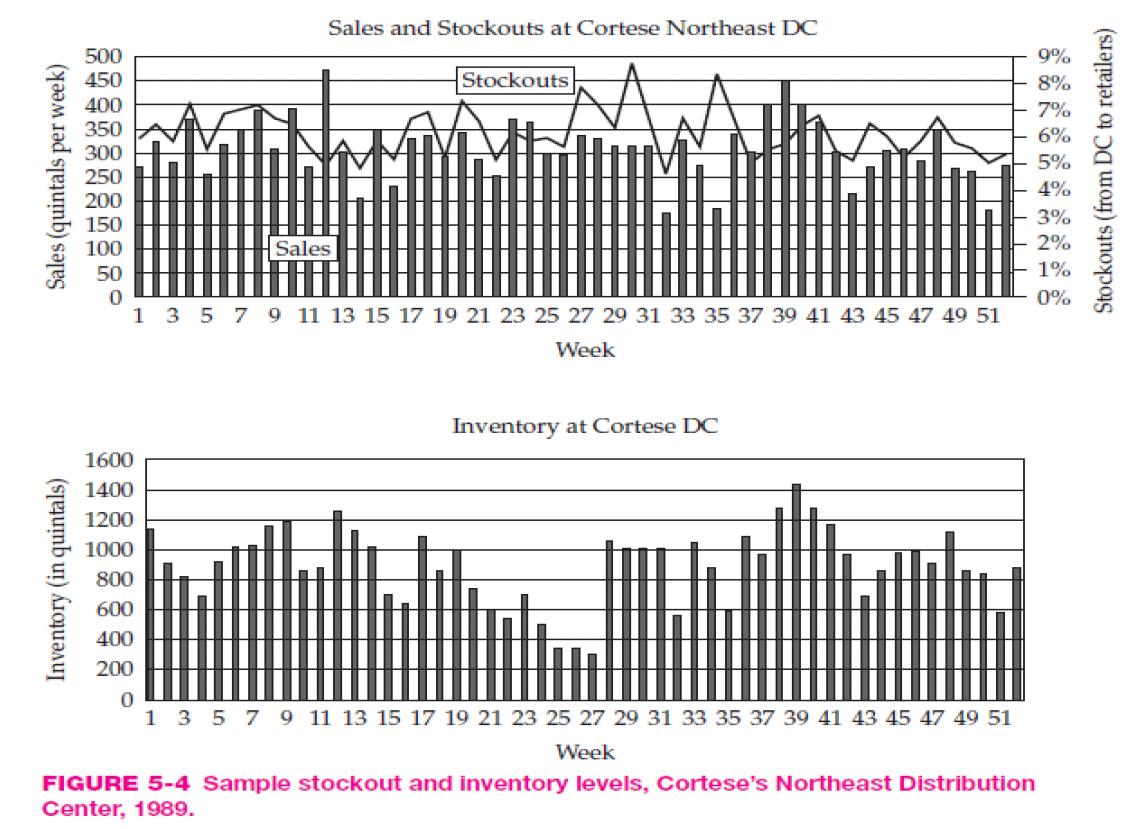

Ordering Procedures: Most distributors, including GDs and DOs, reviewed their inventory levels and placed orders with Barilla once a week. Barilla products were then shipped over an average lead time of 10 days, extending from 8 days after the order to 14 days after the order. Different distributors had varying order volumes, with large distributors ordering several truckloads per week, while smaller ones might order only one. They primarily used simple periodic review inventory systems, and while they had computer-supported ordering systems, they lacked advanced forecasting tools.

Impetus for the JITD Program: Barilla faced challenges due to fluctuating demand for dry products, resulting in extreme order variability. Demand swings strained manufacturing and logistics operations, making it hard to meet unexpected demand spikes and maintain high finished goods inventories during weeks of low demand. Barilla considered asking distributors or retailers to hold more inventory to address order fluctuations, but distributors and retailers were already experiencing inventory space constraints. The proposed JITD (Just-in-Time Distribution) program was introduced by Brando Vitali in the late 1980s as a way to proactively manage the delivery schedules. It aimed to reduce costs, inventory levels, and manufacturing costs. The proposal was met with resistance, particularly from sales and marketing departments. They raised concerns about flattening sales, adjusting to changing demand patterns, increasing inventory risks, and inability to run trade promotions with JITD.

Resistance to JITD: The JITD proposal met substantial resistance within Barilla, especially from sales and marketing departments. Concerns included the fear that sales levels might flatten, difficulties in adjusting to changing demand patterns, and doubts about the readiness of the distribution organization for such a change. Sales representatives were concerned that their roles would be diminished. There were also worries about inventory management, stockouts during supply disruptions, the inability to run trade promotions, and potential cost implications.

Vitali countered these concerns by positioning JITD as a selling tool that enhanced customer service at no additional cost, improved Barilla's visibility, and made distributors more dependent on the company. Despite the resistance, Giorgio Maggiali, Barilla's director of logistics, and his team worked to implement the JITD program by engaging with distributors and seeking their cooperation. However, distributors initially showed reluctance to adopt the new system

TABLE 5-1 BARILLA SALES, 1960-1991 Year 1960 1970 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990t Barilla sales (lire in billions*) 15 47 344 456 609 728 1,034 1,204 1,381 1,634 1,775 2,068 2,390 Italian wholesale price index 10.8 41.5 57.5 67.6 76.9 84.4 93.2 100.0 99.0 102.0 106.5 121.7 128.0

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Based on the information youve provided and the visuals from the case study we can outline the flow of customer demand information in Barillas supply chain and address the causes of fluctuations in or...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started