Question

DUTCH DONOR DELUSION DEEPENS DIVIDE & DELINEATES DECISION DIFFICULTY DILEMMA Developed by Clemons & McBeth In late May 2007, BNN, a Dutch company, announced a

DUTCH DONOR DELUSION DEEPENS DIVIDE & DELINEATES DECISION DIFFICULTY DILEMMA

Developed by Clemons & McBeth

In late May 2007, BNN, a Dutch company, announced a new reality TV show that would feature three patients?all in need of a kidney?competing to be chosen by "Lisa" (who was terminally ill) as the recipient for a kidney she would donate. American Idol-style, viewers would play a key role by texting Lisa their input on her choice. Outrage was expected, and no one was disappointed on that count. In the Netherlands some public health officials and others in government wanted to ban the broadcast or, failing that, disallow the transplant. Around the globe, and in the United States, the reaction was (though not unanimous) strongly tilted against the show and its process as being debased, immoral, over-the-line, shameless, and distasteful. For example, Dr. Paul Root Wolpe, a University of Pennsylvania bioethicist also serving as the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities' president, called the show tawdry.

It turned out that De Grote Donorshow (The Big Donor Show) was a hoax. Lisa was not ill,she was an actress. She had no intention of donating a kidney. The three contestants, all of

whom really were in need of a kidney, were in on the hoax. The chairman of BNN said that they recognized the show was "super-controversial and some people will think it's tasteless," but he continued, "we think the reality is even more shocking and tasteless." The reality he was talking about, and the point of the hoax, was the shortage of organ donations. BNN actually scheduled the show to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the death of a former BNN director, Bart de Graeff, who died of kidney failure after waiting on the organ donation list for years. He was 35 when he died.

Not everyone, before or after the show was revealed as a hoax, was a critic, though. Jeffrey Kahn, director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics, noted that:

It's not all that different from what's happening on the Internet, on sites like MatchingDonors.com, where people looking for organs post their pictures and their stories, hoping a potential donor will choose them. Or there was a guy in Houston who bought a billboard saying he needed a liver, and a family called after their daughter was in a car accident and said they wanted to donate to him.

Regardless of the appropriateness of the show, it successfully raised awareness not only of the organ donor shortage, but also of the murky ethical waters surrounding the topic.

Sometime later, after a court decision to be discussed shortly, in the United States, a (fictional) summit was held to consider the very real issues and statistics involved. Representatives from

the American Medical Association (AMA), bioethicists, representatives from the American Bar Association (ABA), state officials, representatives from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), federal officials, and representatives from various religious and relevant advocacy groups gathered to discuss this life-and-death issue. Here are some of the (real) background facts:

- Prior to the creation of UNOS (a private, nonprofit organization), in the United States there was no systematic process for determining who cadaver organs were allocated to; today, most cadaver organs go to those people on the UNOS waiting list with the appropriate "score" (based on time spent on the list, how desperate the patient's medical condition is, physical distance between patient and organ[s], and medical factors such as blood type and the size of the organ[s].)

- A 1984 law (the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Act) gave authority to regulate the national organ distribution system to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and also prohibits the buying and selling of organs?declaring them a national resource. Organ transplantation is not easy or simple, and requires appropriate facilities, so illegal sale of organs is not really a problem in the United States. However, geography has played a key role both because of medical and cost reasons and because of a sentiment in many states that those states that did a good job of encouraging their citizens to be organ donors should benefit their citizen-patients first. In 2000, an attempt that would have overturned the regulations that put the HHS (and by contract UNOS) in control of the organ delivery system failed in the House of Representatives.

- Beginning in December 2014 all adult kidney candidates on the waiting list are assigned a score based on four factors: candidate age, length of time on dialysis, prior transplant of any solid organ, and current diabetes status. Essentially, those with the best score are matched with donor kidneys with the best score (affected by things such as the age of the donor and their health). The goal was and is to increase how long people live after getting a transplant. Donor kidneys not scoring in the top 20 percent are not affected by this, nor candidates not in the top 20 percent. (Retrievedfromhttp://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/contentdocuments/kas_faqs.pdf[accessed November 29, 2015].) Some see this as simply being age discrimination.

- Thousands of patients in the United States still die each year waiting for organs that never become available, even though a single donor can save up to eight lives, and none of the major religions (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, Mormonism, or Hinduism) are opposed to it (www.core.org). Tens of thousands are waiting right now.

- Some European countries have laws creating "presumed consent," which means that upon death your organs become available unless you have taken active steps to forbid it. However, in the Netherlands, and in the United States, donors (or their families) must give their consent for organ transplants.

- Organ transplants from live donors (who normally pick the recipient) have a higher success rate, and since the year 2001, the number of transplants from live donors has exceeded the number of transplants from cadavers. Still, patients are increasingly seeking live donors through various means (getting local news media assistance in putting their story out, Internet appeals, television and newspaper ads, or even a billboard). This is causing concern among some, multiplying the already significant moral and ethical concerns surrounding this issue.

Concerns include the following:

- Should people with more money, people who may be more attractive or more articulate, have greater access to this scarce resource? Should the United States legalize, as is done in some poorer countries, the actual selling of kidneys?

- Isn't this just typical capitalism, wherein both parties can agree to a mutually beneficial agreement?

- If all other things are equal (e.g., medical compatibility, time spent on waiting list, geographical proximity), what other factors are appropriate for consideration?

- Should ability to pay for the cost of the medical procedures be considered, or should the working poor, without insurance, be ineligible?

- Could a simple monetary cost-benefit ratio (social utilitarianism) be used to decide such matters (e.g., the cost of the medical care versus the candidate's ability to generate income and taxes or other tangible benefits to society)?

- Could there be a problem with determining who is most likely to recover (and life expectancy)? That is, might attending physicians have biases? Might things like the kidney allocation formulas be discriminating against older people in a way that violates our values? Or, given that organs such as kidneys are a scarce resource, shouldn't we look at things such as age to try to maximize the payoff from that scarce resource?

- Where should the power, the discretion, lie in this situation? With experts, with a board of both physicians and nonphysicians, with elected representatives, with local/state or national officials?

Now, back to the summit and its (fictional) origins. As the Supreme Court has moved erratically toward greater state control in some areas and greater federal control in others, a lawsuit by a grieving spouse of someone who died waiting for an organ transplant worked its way onto the docket. To the surprise of many, earlier this month the Supreme Court, in yet another 5-4 decision, found that the 1984 law discussed previously was unconstitutional because such decisions belong in the sphere of rights delegated to the states. This decision also means that formulas such as those created by UNOS affecting kidney allocation have no federal legal weight behind them. That decision led to the calls for a summit to decide how to proceed. The problem, though, is that no one expects a quick consensus (if any consensus at all), and meanwhile decisions have to be made. Today, we are back to the old ways where the patient's community status, geography, medical personnel's biases and idiosyncrasies, and luck seem to rule the day.

However, in your state (choose a state) the governor and state legislature decided they needed to act quickly, so they created a state commission charged with developing a state policy that would govern transplants from both cadavers and live donors, including deciding how to deal with the issue of organ export and import criteria and relations. Even this move left a system in crisis. While the national summit and state commission go about their business, decisions must be made on a daily basis. That's where you come in.

When the governor heard that this particular group of talented, intelligent, students?all of whom were only enrolled in this class?were available, a decision was made. Congratulations! You are now a member of the Organ Transplant Crisis Decision Team (although you may also choose to work alone, group work is encouraged). Your job is threefold:

- Create a crisis policy to get the state through the period prior to the commission's policy being developed and implemented. Depending on how the summit goes, your policy could end up setting the agenda for the state commission.

- Decide a heart transplant case among three candidates who, like the three candidates on the Dutch television show, all need an organ transplant very soon or death will result.

- Prepare an explanation of your decision on the organ donor case.

A note from the governor suggested that it would be unwise to make a decision that would not comport well with the ultimate policy criteria you establish (in other words, spell out the policy criteria you establish in your report).

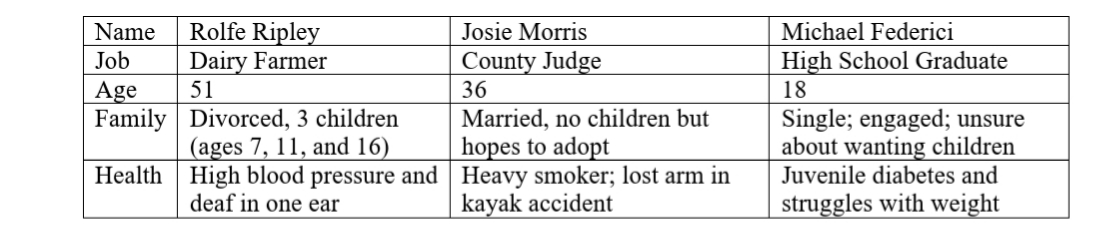

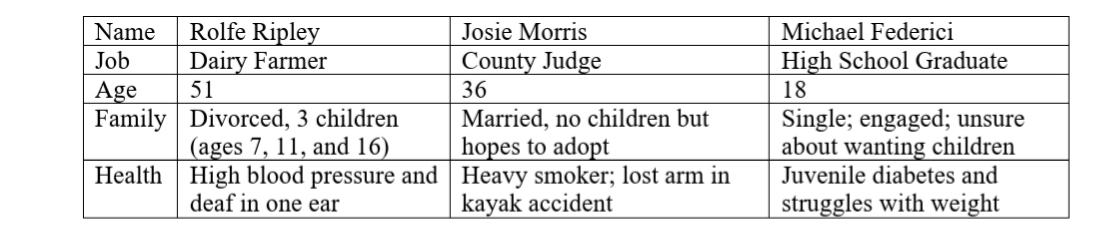

The three candidates are all in need of a heart. All three are compatible matches, medically. All three have equal chances of surviving approximately 25 to 30 years if they get the heart. Remember, there is only one heart.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started