following comment from LRN appears under the "The GoldPlus Proposal" heading:

The semi-urban/rural market is over Rs.36,000 crores. Furthermore, the traditional plain gold jewelry segment is around 80% of the overall market. This market segment only wants ethnic design plain gold jewelry at a competitive price. To serve this segment, we need to leverage our supply chain capabilities and compete on price.

Please replace this comment with the following from my version of the case (differences are italicized where possible):

The urban jewelry market is estimated at about Rs. 24, 000 crores. The semi-urban/rural market is over Rs.36,000 crores. Furthermore, the traditional plain gold jewelry segment is around 80% of the overall market, or about Rs. 48, 000 crores. This market segment only wants ethnic design plain gold jewelry at a competitive price. To serve this segment, we need to leverage our supply chain capabilities and compete on price.

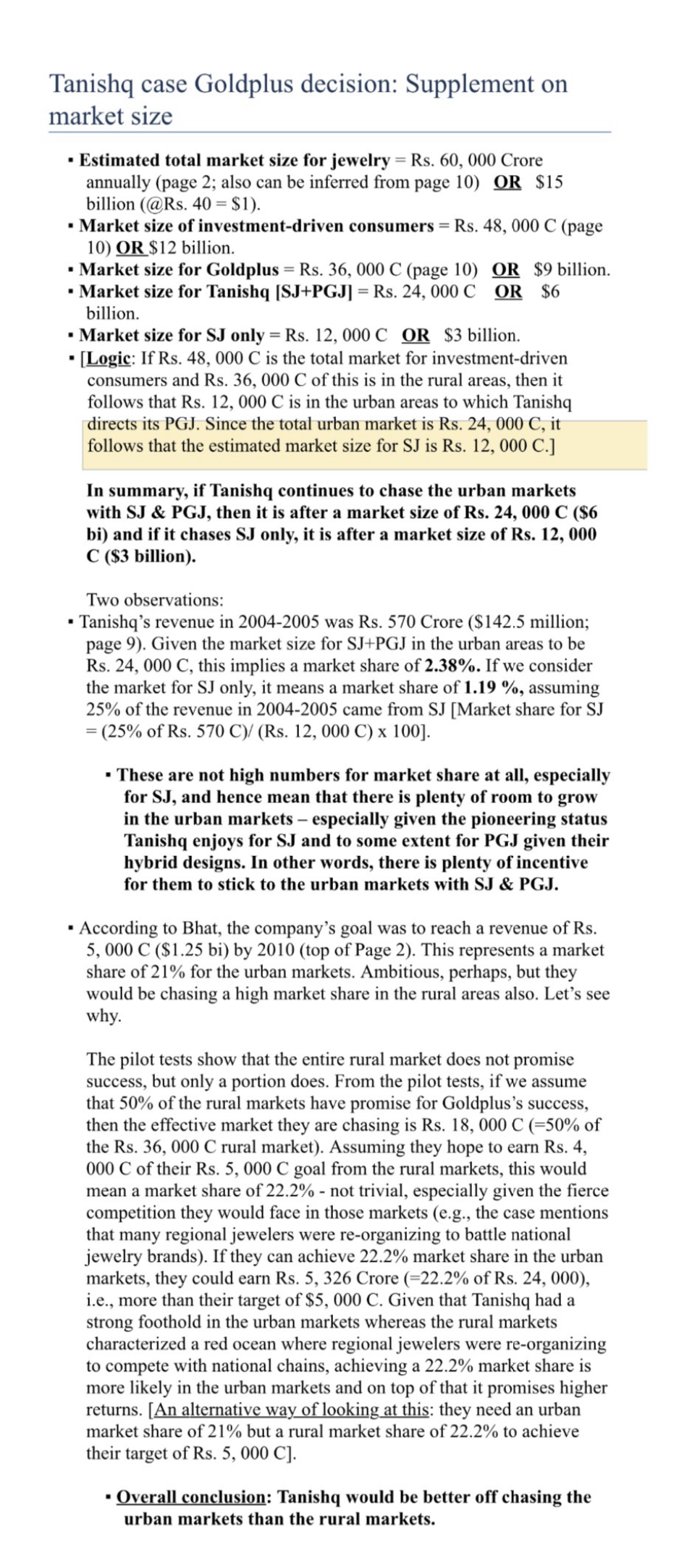

In my evaluation of the Goldplus decision, I did an analysis on market size based on some information from the case, with the help of some assumptions. One piece of information that affected my analysis (specifically, the second bullet point in the supplementary document containing my analysis of market size) was Goldplus' performance in the pilot test. Now imagine that after piloting Goldplus in Erode and Ratlam, Tanishq managers piloted the brand in 3 more small to wns that are very similar to Ratlam and performance in the three additional towns was very similar to that in Ratlam. Clearly explain, with suitable numbers/calculations as needed, as to how this new piece of information would affect my analysis of market size and conclusions?

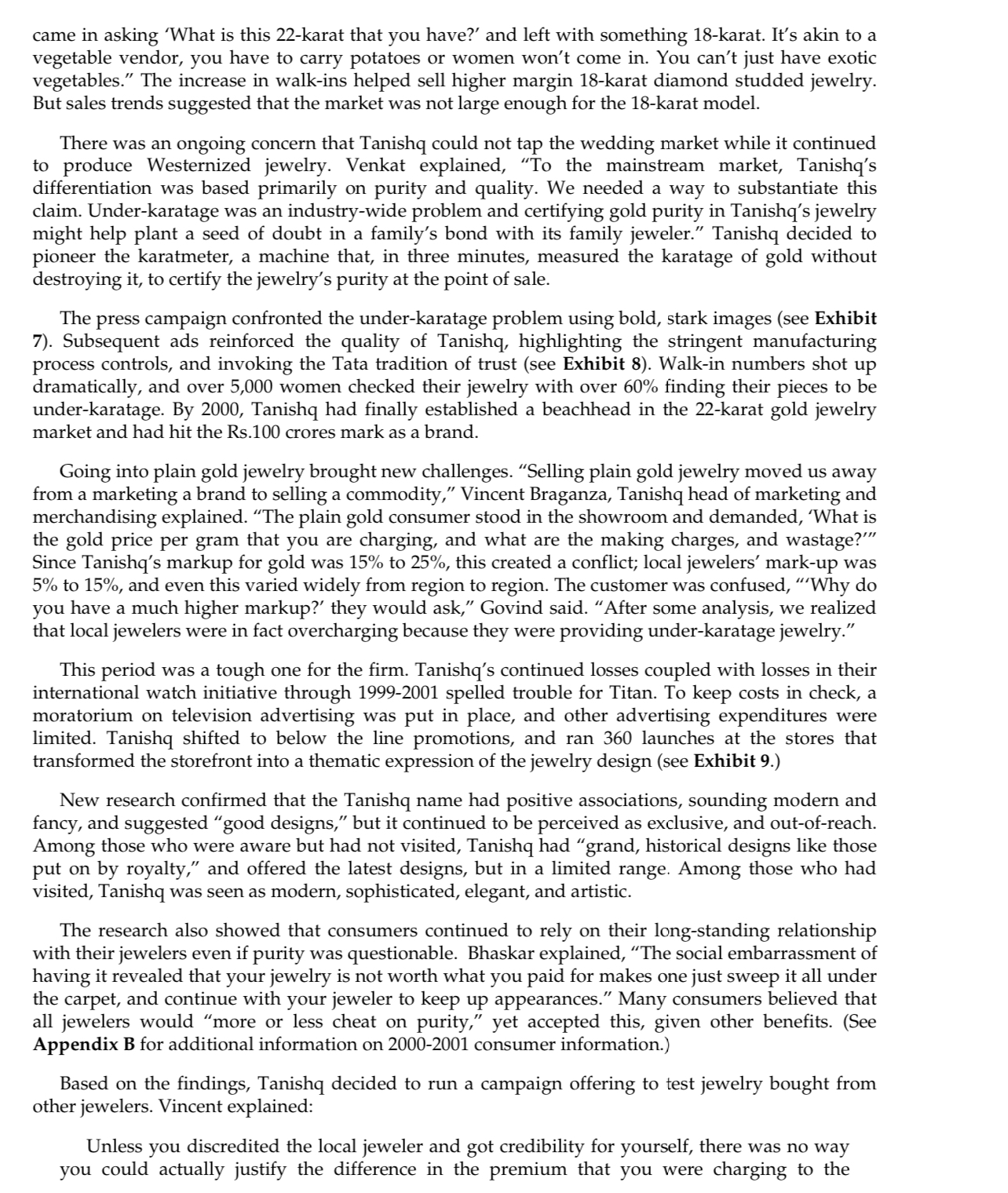

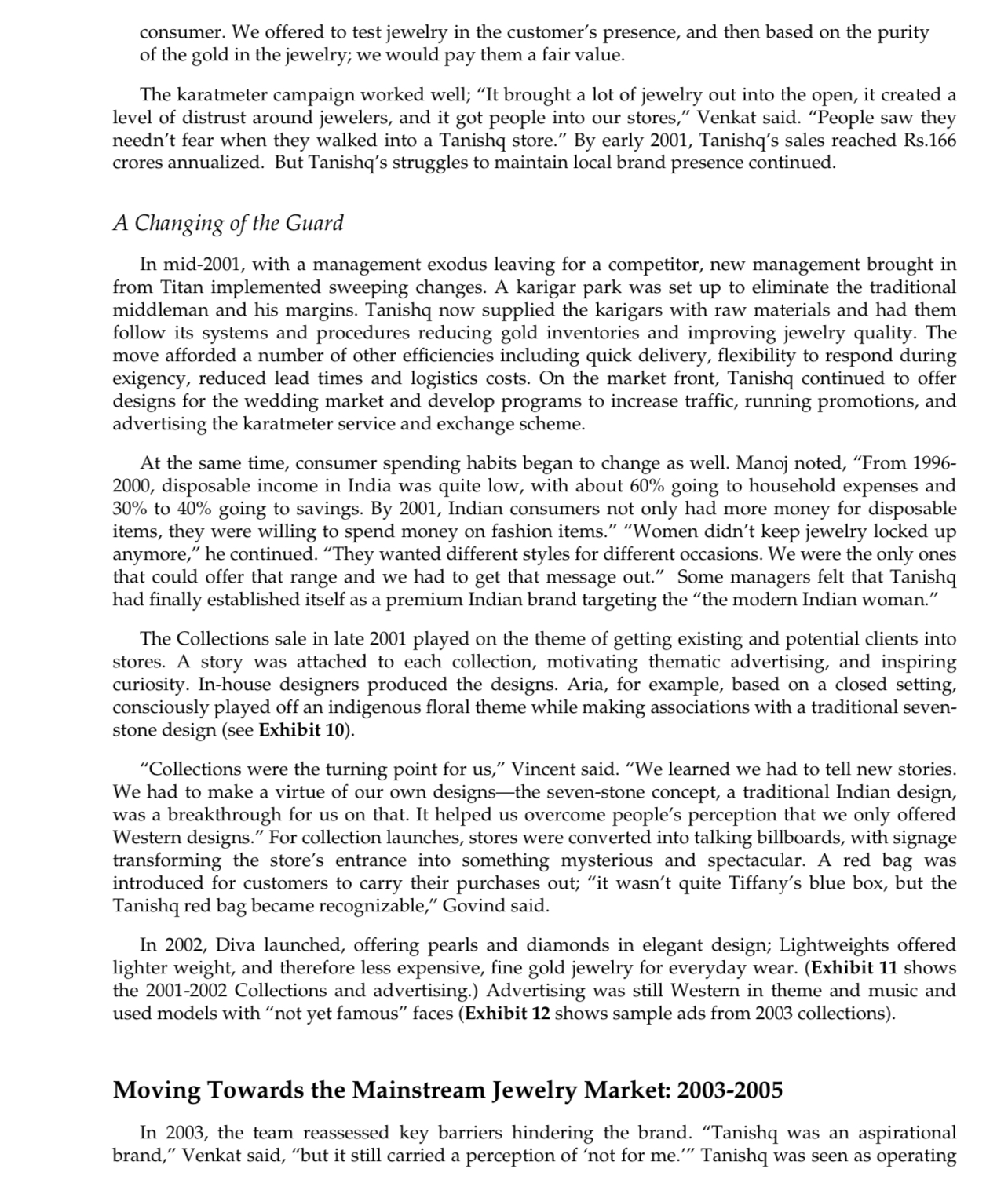

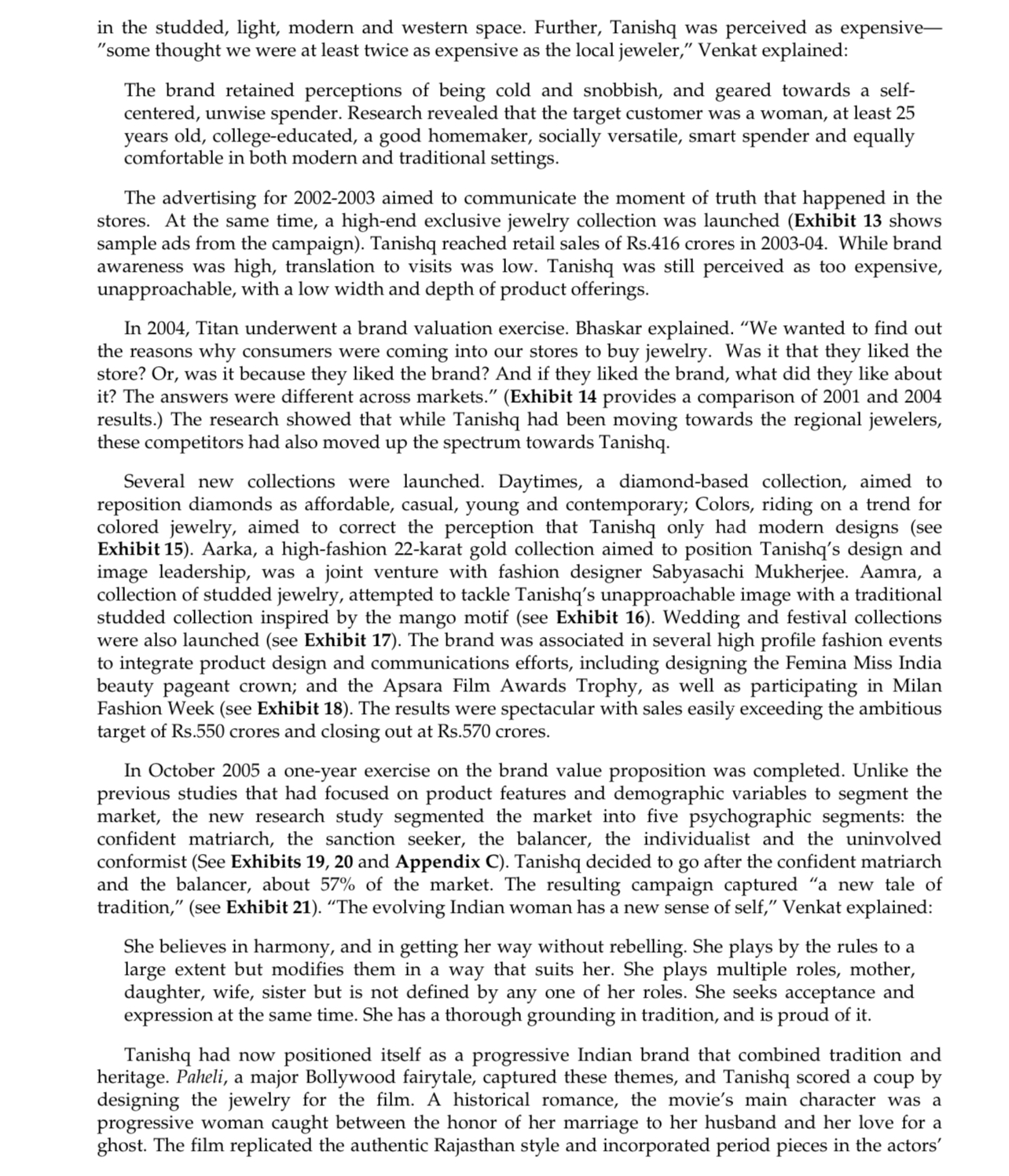

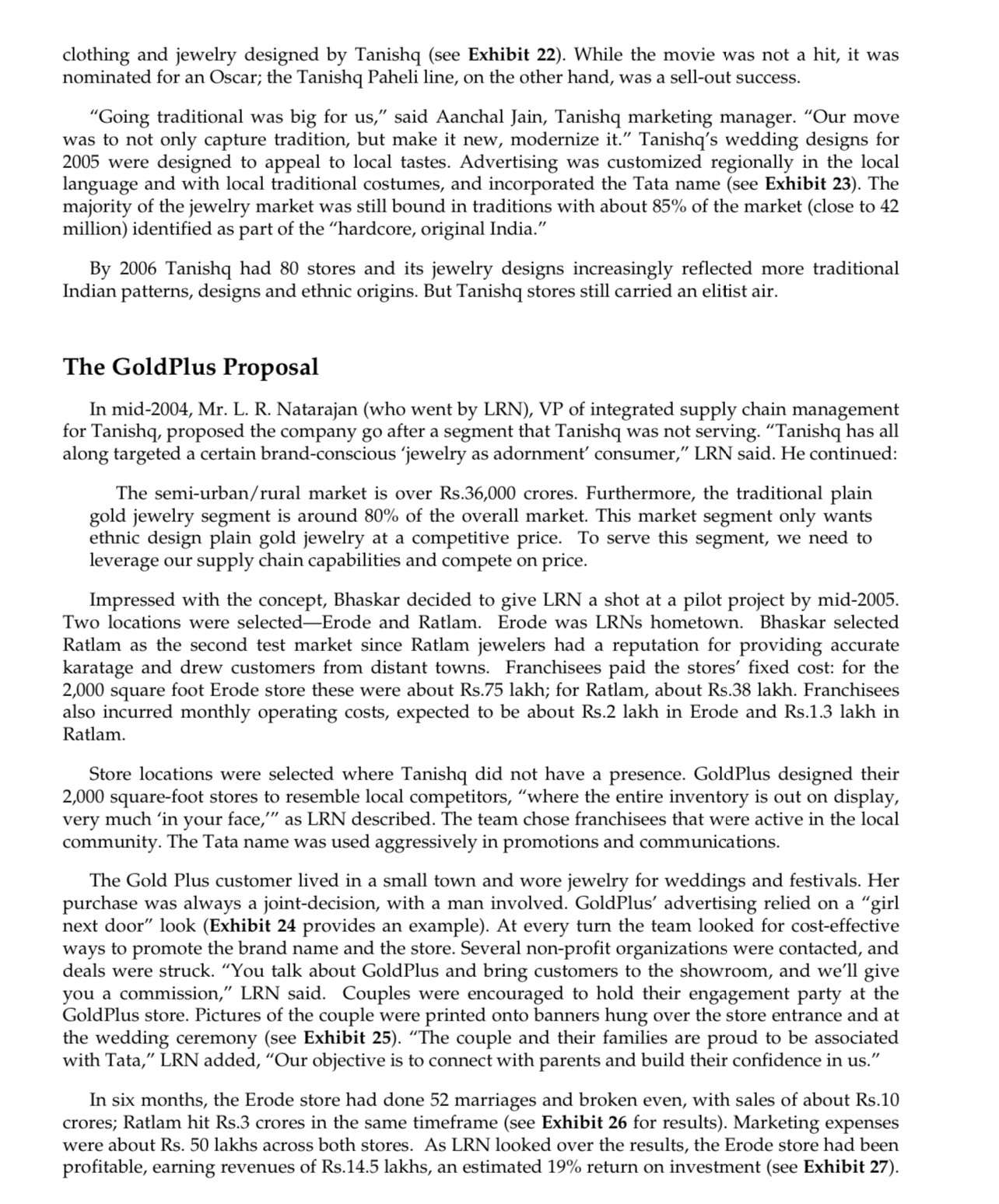

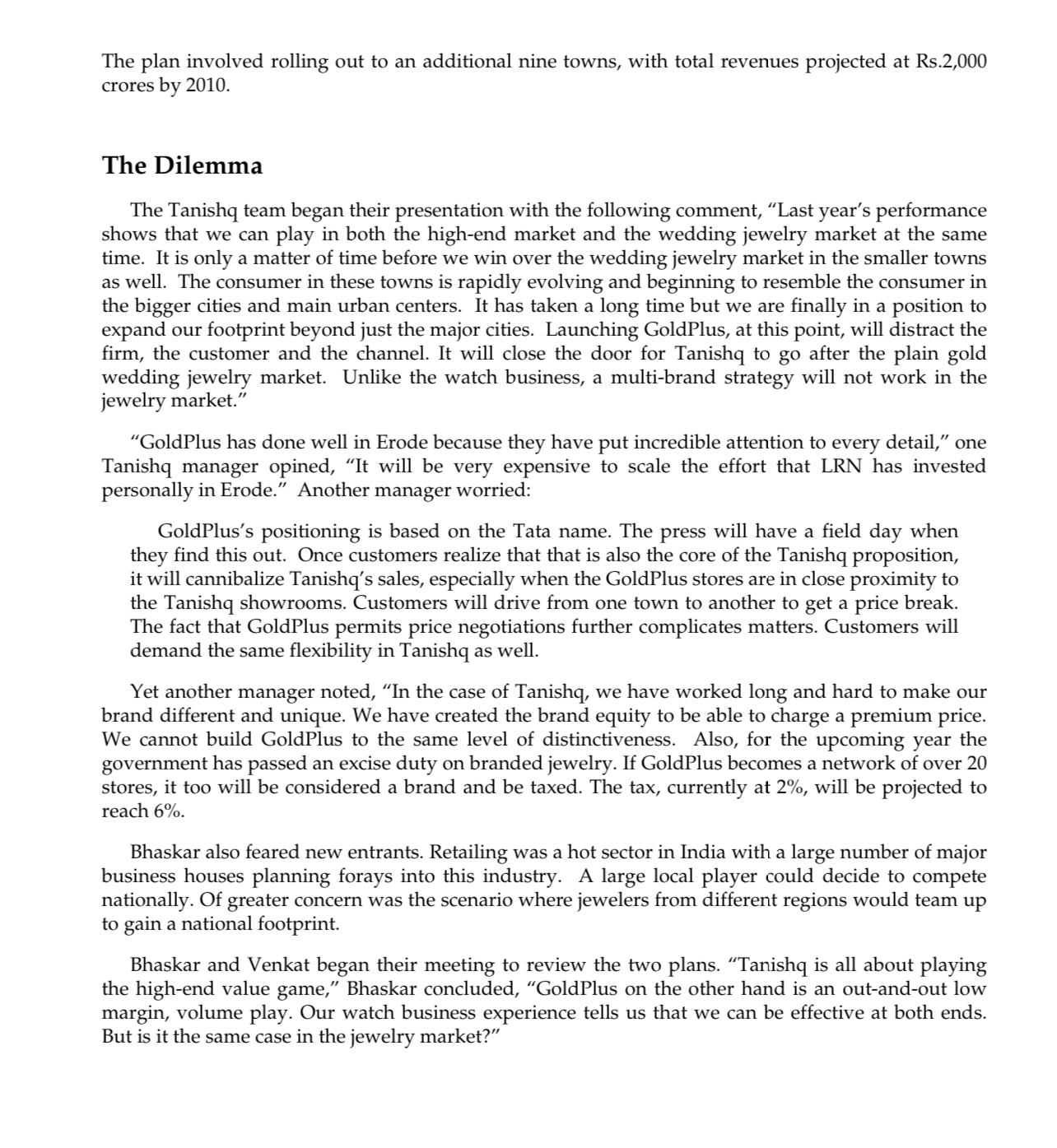

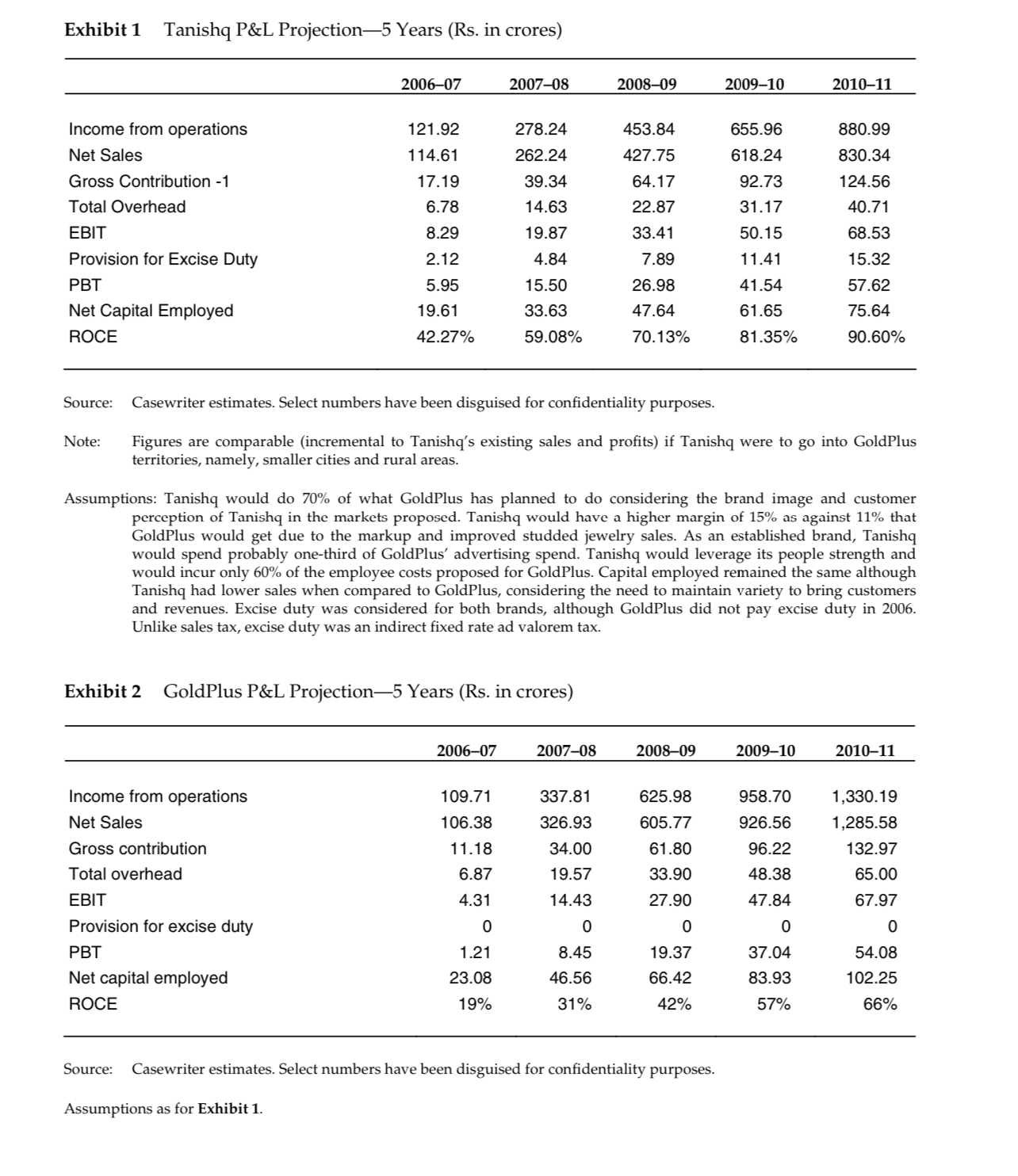

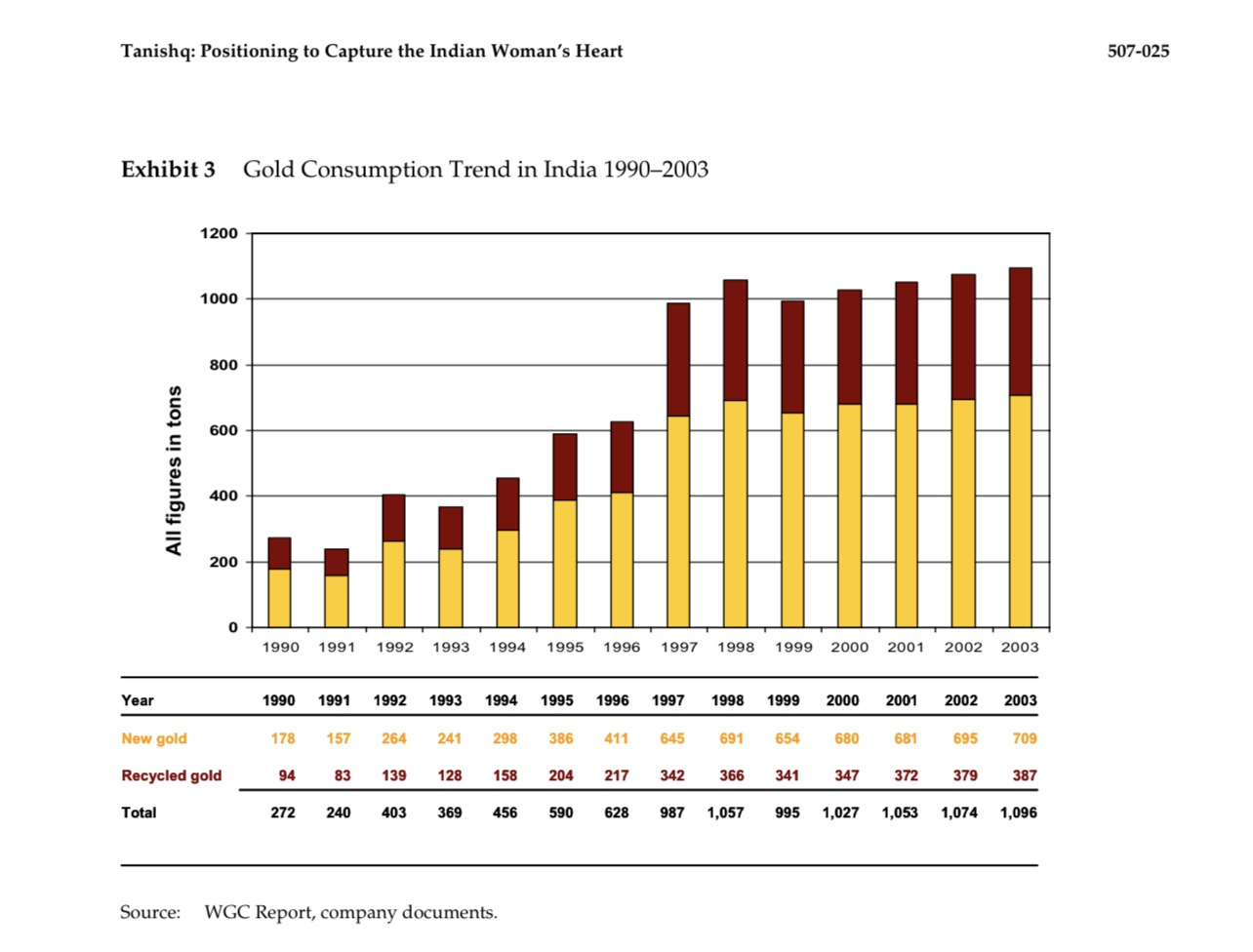

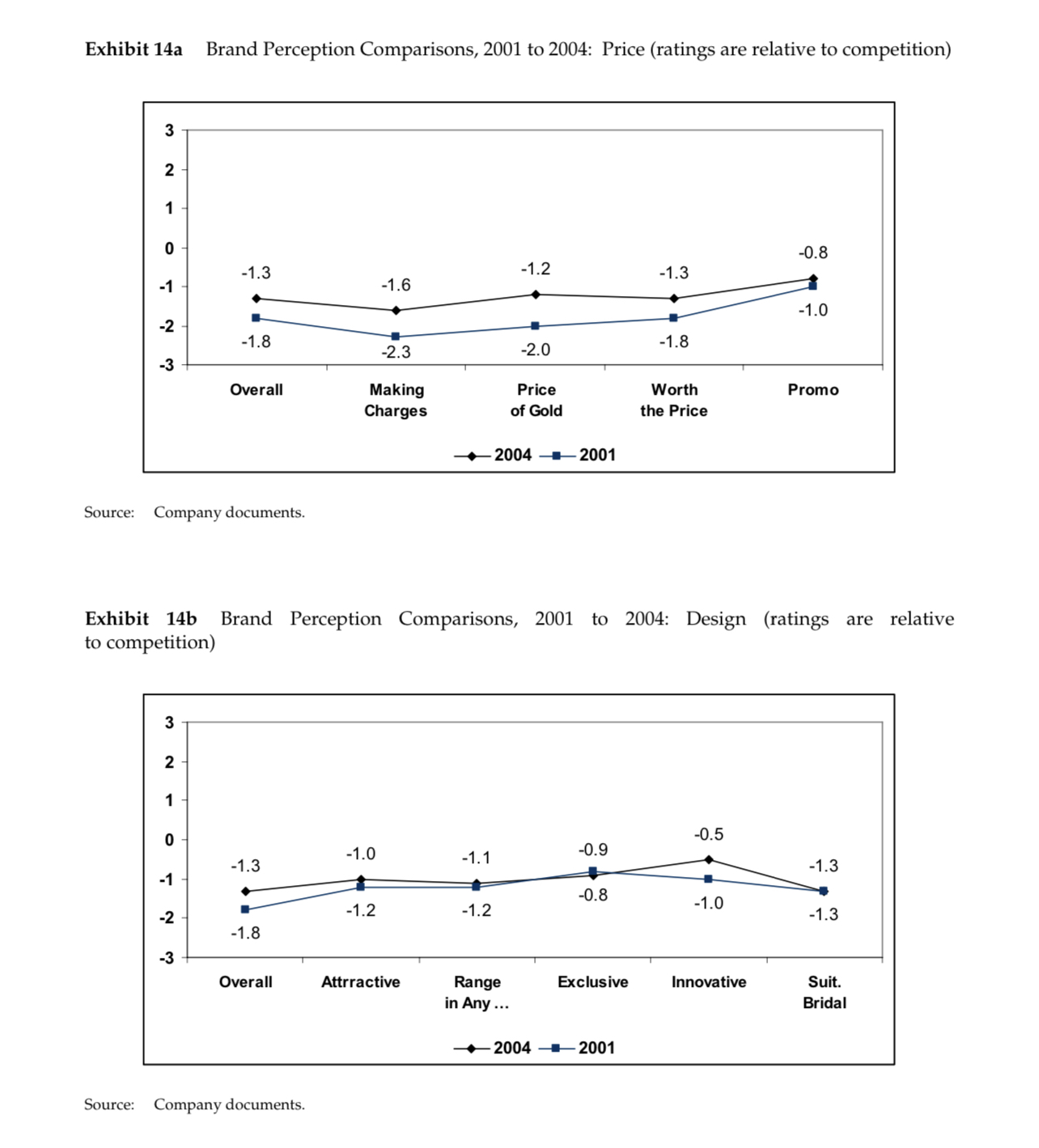

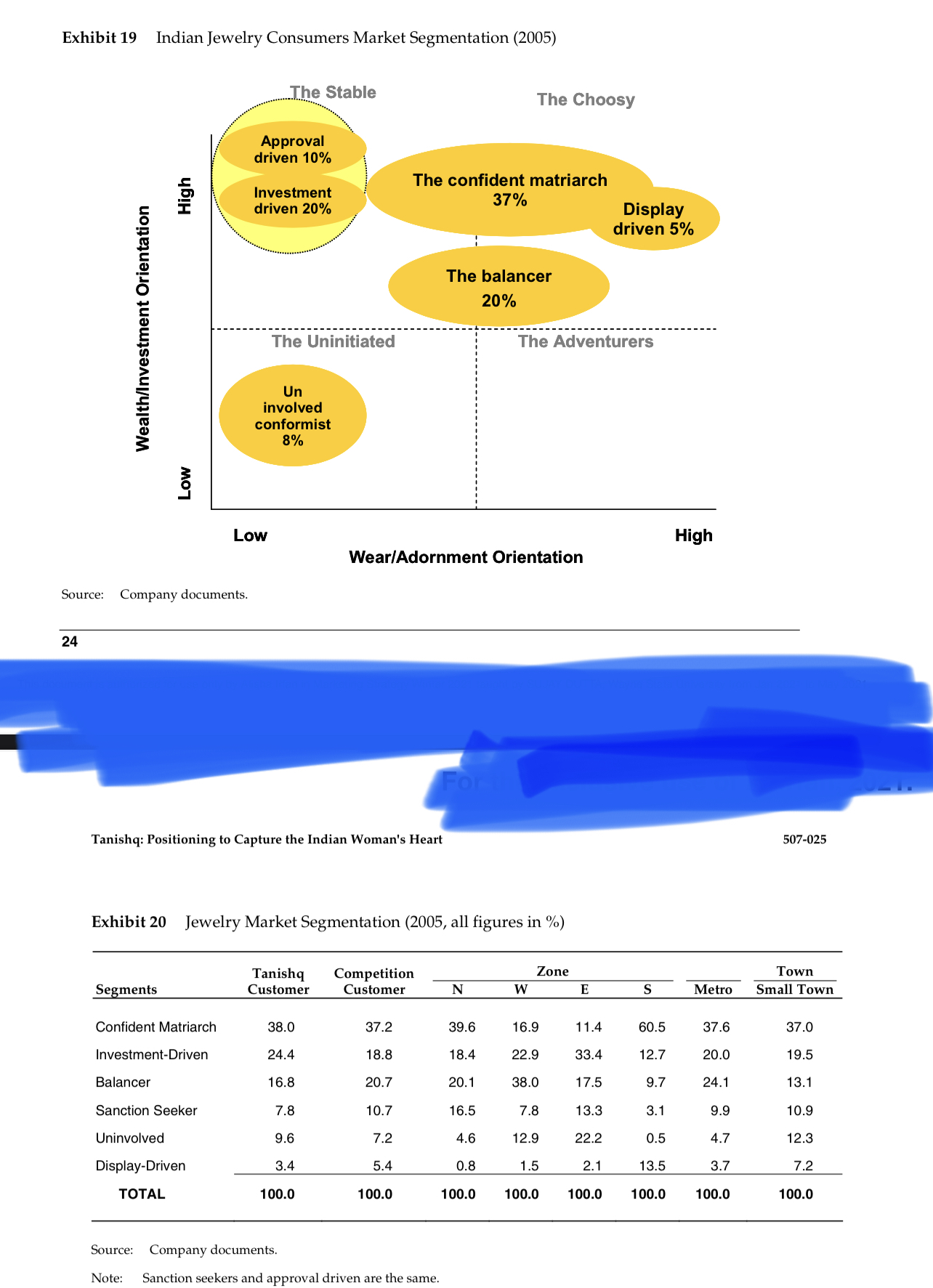

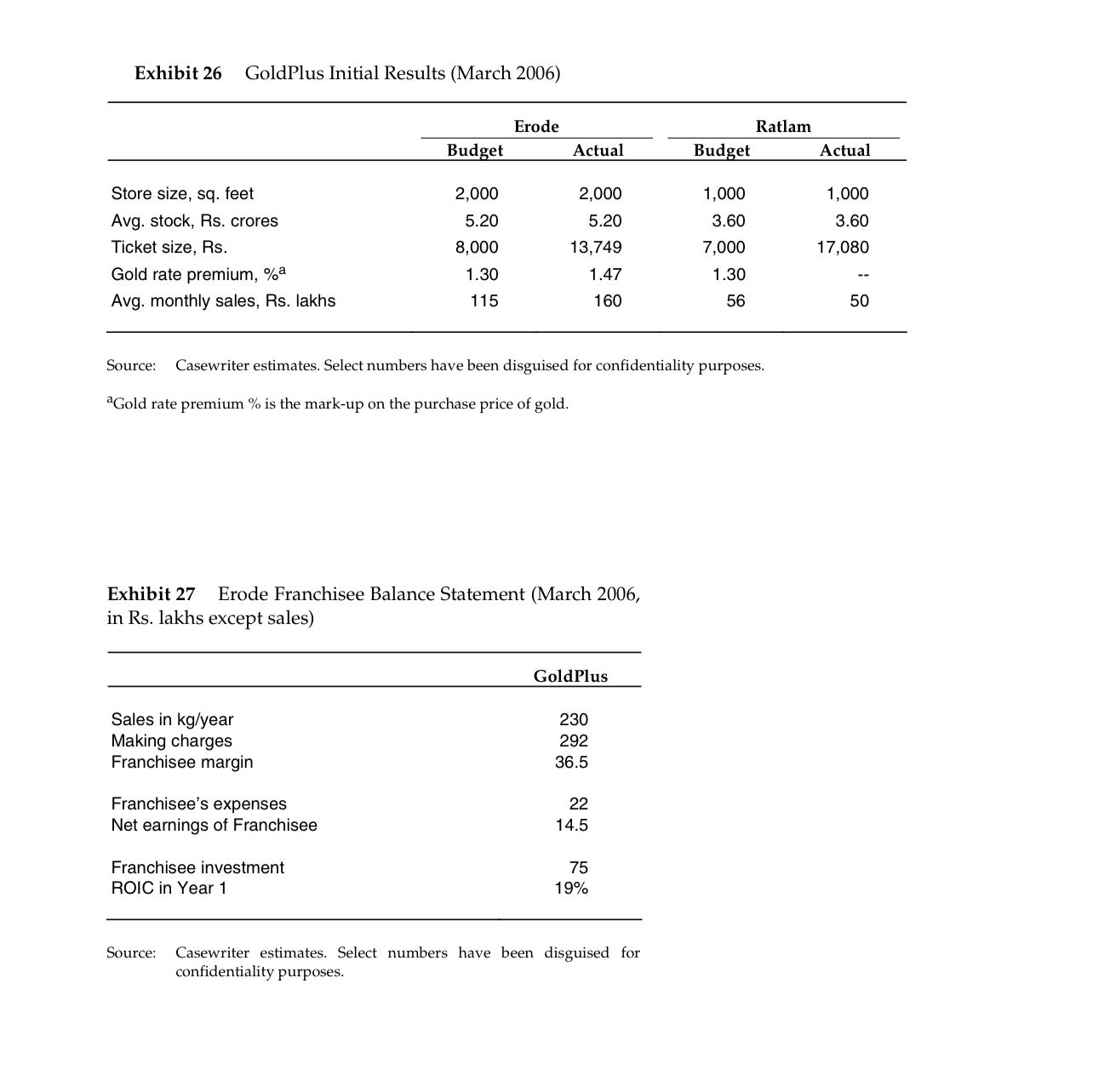

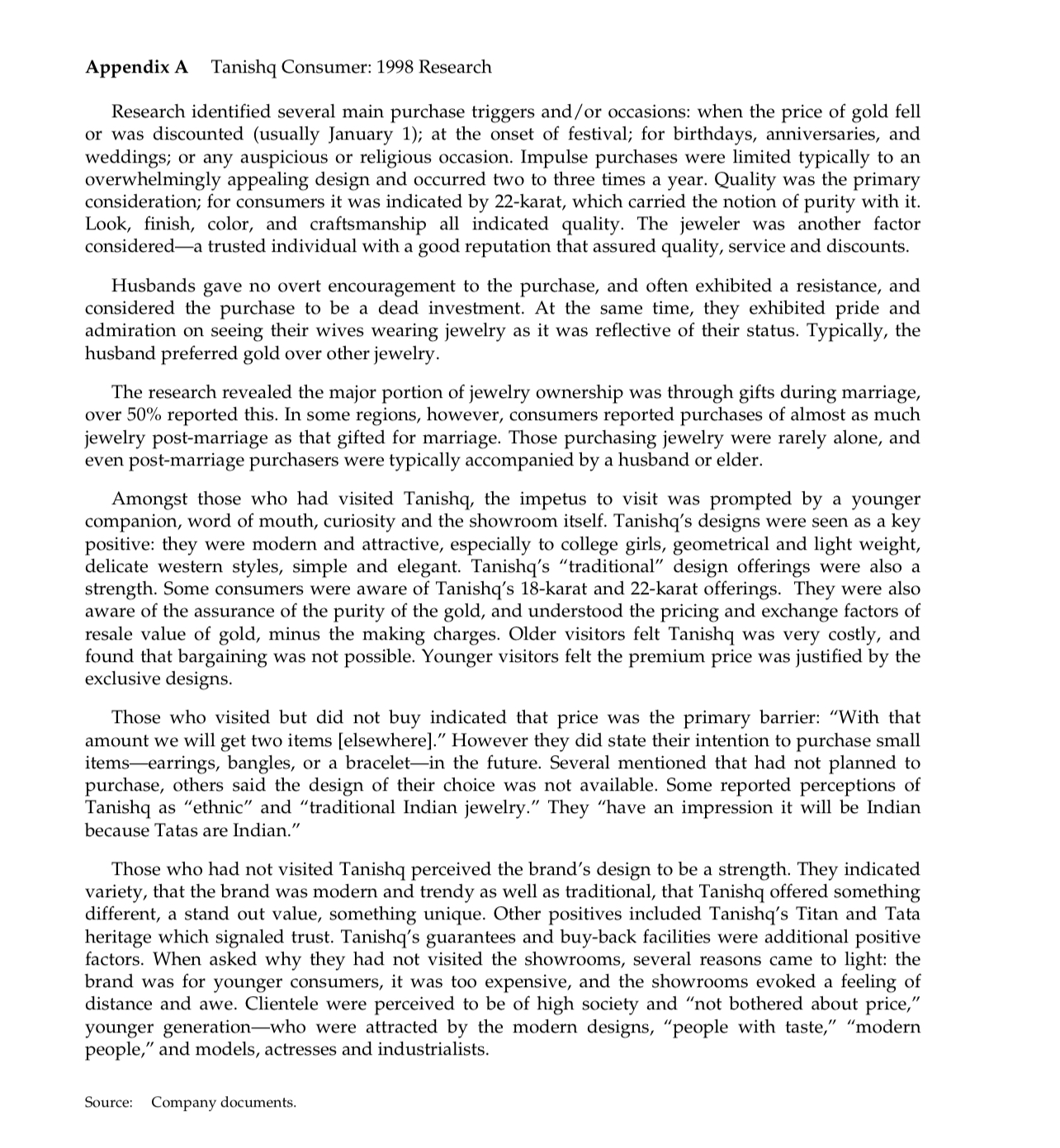

Tanishq: Positioning to Capture the Indian Woman's Heart On a warm spring day in March 2006, there was excitement in the offices of Tanishq, the jewelry division of India's leading watchmaker, Titan Industries, a subsidiary of the Tata Group, one of India's most respected business houses. C. K. Venkatraman (V enkat), head of Tanishq, watched his brand marketing team pulling the last of their presentation slides together before heading across the plaza of Bangalore's Golden Enclave to meet with Titan managing director, Bhaskar Bhat. Tanishq was the country's only truly national jeweler that sold gold and gem-studded jewelry in boutiques across India. Initially, Tanishq had targeted a more Western consumer, which had evoked a "Nice, but not for me\" reaction from Indian women. The brand had undergone several strategic retoolings over time to reach out to the traditional but modern Indian woman segment and the Tanishq team was optimistic that they had finally positioned Tanishq squarely at the heart of the Indian wedding jewelry market. At the same time, a skunk works project team within Tanishq had successfully launched GoldPlus, a modest brand positioned to serve the plain gold wedding jewelry market in India's smaller cities. A visible strain had developed between the Tanishq and GoldPlus teams as both brands returned positive results. The Tanishq team, in the midst of a campaign to capture the wedding jewelry market, felt that the GoldPlus launch would confuse the marketplace and distract the organization. They were also reluctant to give up the opportunity for Tanishq to serve the smaller towns. The GoldPlus team argued that their model was superior to Tanishq's when it came to serving the wedding jewelry market. (Exhibits 1 and 2 provide cost and revenue projecljons for Tanishq and GoldPlus.) They wanted Tanishq to stay on course with an upmarket focus on \"jewelry for adornment\" in the major cities and towns, while GoldPlus pursued the "gold jewelry as investment" opportunity in the smaller towns. Bhaskar and Venkat knew that this was a watershed moment for the firm. Should Tanishq or GoldPlus pursue the plain gold wedding jewelry market in the smaller cities and rural locations? Their decision would impact how the firm would reach the ambitious goal set by Bhaskara billion dollars (Rs.5,000 crores) in sales by 2010 (in March 2006, US$1 = Rs.44.5). Jewelry in India The Indian gold jewelry market was estimated at Rs.60,000 crores annually. Decades of socialist- style rule had meant steep taxation on income and assets, and many Indians had converted cash into gold. When the Indian government began to liberalize its economy in the early 19905, imports of gold became easier and the industry started to thrive; demand surged 45%, to 737 metric tons, making India one of the fastest growing gold markets in the world. By 2000, according to the World Gold Council, India held at least 7% of the world's gold stock, or about 9,500 tons. Some sources put the actual figure at closer to 30,000 tons.1 (Exhibit 3 shows gold consumption trend in India.) Jewelry was very important in an Indian woman's life, considered "streedhan," Hindi for \"woman's wealth," in a society where women typically did not own property or other assets.2 At minimum, a wedding trousseau contained at least two gold bangles, a gold necklace, earrings, a ring and a nose pin-an investment of about $2,550, in a country where per annurn capita was about $350. Gifts of gold jewelry and watches were customary as well; Dhanterasthe first day of the festival of Diwaliwas considered the biggest gold-buying day in the world. While there was no truly national competitor, Tanishq faced local competitors that were bigger than Tanishq locally. In addition, there were over 25,000 family-owned independent jewelers. While women were the primary target for jewelry, men were the buyers. On the occasion of a wedding purchase a mother, father and bride-to-be would visit their family jeweler for several hours for a review of the design selections. The selection would then be narrowed down to one or two designs. The jeweler then scheduled a visit to the family's home so that other family members might review the choices. Ticket prices ran anywhere from a lakh (100k) to several crores (100,000k) of rupees. Indian jewelers were essentially retail stockists. Vendors, who owned the inventories, supplied to the jewelers through a consignment arrangement. At the back end of the supply chain was a group of over 3 million craftsmen or karigars, most being born into the trade and working from their homes. A head karigar controlled 10 to 20 karigars, and a vendor controlled about 34 head karigars. When jewelers would show designs to the vendor, he would take the sketches back to the head karigar who used his knowledge of each of his karigar's specic abilities to allocate jobs. The head karigar priced work on the basis of complexity of design; karigars typically received R530 per gram of gold for work, with the best karigars receiving up to R540 per gram. Once the rates were fixed, the vendor then set a timeframe for delivery depending on demand. Jewelers had long-standing relationships with their vendors, and remained very loyal to their preferred vendors. Titan Industries Titan was incorporated in 1984 as a joint venture between the Tata Group and Tamil Nadu Industrial Corporation (TIDCO). Prior to Titan's entry, the Indian watch market was predominantly mechanical. Quartz watches, by then, was the global standard. With its markets closed to global brands, however, the Indian market lagged behind. Manoj Chakravarti, Titan VP, explained, We had to educate the Indian customer. We set up service centers to assuage customers' concerns with quartz. We changed the retail environment and the way Indians thought about and bought watchesfrom buying inexpensive utilitarian watches in a watch shop located in a watch market to actually walking into exclusive watch showrooms in high rent retail districts, viewing a wide range of variety, and buying expensive time pieces that made a statement. Within a decade, Titan redefined the Indian watch industry and quartz became the new standard. Bhaskar elaborated, \"In the early years, our core customer was an "Indian\" Indian, and \"not a global Indian,\" typically upper-middle class. Over time, we have repositioned Titan as being more than just a timepiece. We now want the customer to think of gifts, accessories, and fashion when they walk into our stores. Our customers now include college students and young professionals as well. We have several additional brands in our portfolio: Sonata, our lower-end brand, Fastrack, aimed at a younger afuent market, and Nebula, our high-end gold collection." Flush from their success in watches, Titan managers began to think about international expansion in the early nineties. Bhaskar recalled: In Europe, we were struck by the huge gap in prices at which studded jewelry and solid gold watches were being sold by the established brands, and our costs to actually make and sell them. So fashion jewelry and jewelry watches for the European market appeared to be an opportunity to create a complementary revenue stream. We also needed gold for our domestic gold watch collections, and exports would get us gold import licenses from the government. Launching a brand in Europe was expensive, so the company decided to enter as a private label supplier. But management underestimated several factors including significant pricing pressures, high frequency of new product introductions, and demanding customers that needed their orders serviced at very short notice. The presence of other low-cost Hong Kong based competitors only compounded the problems and sales were below targets. The project was doomed from the outset. With the lifting of controls in the domestic market, Titan shifted its attention to the domestic jewelry market in 1995. Jewelry watches under a new brandTanishqwere introduced, targeted at India's "super haves" (the very high-end consumer). Venkat explained: We positioned the Tanishq watches as jewelry that tells time. Our target market was all urban households with an income of over 1 lakh rupees per month. We wanted the product to be perceived as a premium watch with \"high snob value.\" Our communication strategy pegged the brand as an ego satisfier, above the mundane and utilitarian. The advertising campaign generated high awareness and won several "campaign of the year\" awards (see Exhibit 4). However, sales did not follow and the watch experiment was a disaster. "In retrospect, it was a design problem," Venkat explained. \"The watches were very heavy and appeared clunky and the prices were too high. Generating high awareness also led to an unanticipated negative consequence subsequently. For a long time, consumers thought Tanishq was just about watches.\" The Move from Watches to jewelry Putting the two failures behind them, in 1996 Titan management decided to manufacture and market precious studded jewelry under the Tanishq brand. Bhaskar explained, \"plain gold jewelry offers little opportunity for differentiation. Also, everyone knows the price of gold. The customer then adds labor and wastage and establishes the base price leaving the jeweler with no pricing power. Studded jewelry is a different story altogether. Customers don't know how to value gems. There is also the opportunity to be innovative in design. 507025 Tanishq: Positioning to Capture the Indian Woman's Heart Tanishq's decision to get into the studded jewelry impacted the choice of gold used. The Indian gold jewelry market was based on ZZZ-karat gold and anything lower was considered junk. Studded gold jewelry, however, was based on 18karat gold because 22 karat gold was too soft to hold gemstones. As the rst national jewelry brand, the challenges were twofold and formidable: establish Tanishq's credentials as a differentiated jeweler; and, educate consumers and get them to make a paradigm shift in usage and attitude. Yet, the company forged ahead. Venkat explained, "We had successfully overcome similar barriers in the watch business. We felt condent that we could do the same in jewelry and change the Indian jewelry market standard from 22-karat to 18-karat; from predominantly plain gold jewelry to studded jewelry; from traditional designs to Western designs." Set up as a separate division, with an independent marketing team and a stateoftheart manufacturing plant with specialist designers and the Titan retail network in place, all systems were go. In February 1996, Tanishq launched its first 18-karat exclusively-designed gem-set jewelry range. The offering was positioned as "adornment the both body and the mind.\" The jewelry was distinctly western in style and design (Exhibit 5 shows a sample). In July 1996, Tanishq opened its first boutique in Chennai. Traditionally, Indian jewelers had used their family names, uSually male, as their brand. Unlike this trend, Tanishq was markedly feminine: ""tan for body in Hindi, and "ishq" which meant love. Advertising campaigns focused on creating desirability, and communicating that the Tanishq boutiques \"were as precious as the Tanishq jewelry itself." Accompanying ads depicted women as art forms to display Tanishq, and sought to create mystery and intrigue around the brand (Exhibit 6 provides examples). Indian consumers did not perceive 18-karat jewelry as suited for weddings and festivals. "The consumers were stuck on 22karat jewelry," Venkat explained, "Also, our boutiques were like 5star hotel lobbies: intimidating and exclusive, with limited inventory on display. The consumer was used to stores being crammed with jewelry on display in glass showcases that ran the entire length of all the walls. Furthermore, our designs were considered too Western eliciting a 'not for me' reaction.\" Repositioning Tanishq: A Gem of an Opportunity? As challenges continued, there was growing consensus that Tanishq had to offer ZZZkarat to play in the larger market. By June 1997, Tanishq piloted an offering of 22karat plain gold jewelry, with about 400 designs, with an additional 1,000 designs in 18karat diamond studded jewelry. A multimedia campaign launched in both television and press focused on the most traditional designs in an attempt to counter the Westem-design perception many held. An inaugural offer was promoted in an attempt to increase walkins and purchases. "We tried to dodge the 'not for me' perception without having to offer the full range of bridal suite jewelry like traditional jewelers,\" Venkat explained. "We were still focused on jewelry for adornment, rather than investment. Our brand was about 'looking good, feeling good all the time,' unlike wedding jewelry which was something you wore onceand then out of sight, out of mind." Average ticket prices remained much lower than typical wedding purchases, but walk-ins had increased. Sales rose to R524 crores by April 1998, however the mainstream buyer still eluded the firm. Appendix A provides results of the 1998 qualitative research study. \"18~karat jewelry was closer to costume jewelrynot precious," Venkat explained, "and we still carried an association with jewelry watches. We were seen as specialty, a 'change of pace' productrather than mainstream." [n 1999, the group renewed their push for the ZZZ-karat plain-gold market and included Indian- inspired designs. "Offering 22-karat jewelry raised curiosity," Govind Raj, Tanishq VP noted, \"people A came in asking 'What is this 22karat that you have?' and left with something 18karat. It' s akin to a vegetable vendor, you have to carry potatoes or women won't come in. You can't just have exotic vegetables." The increase in walk-ins helped sell higher margin 18-karat diamond studded jewelry. But sales trends suggested that the market was not large enough for the 18karat model. There was an ongoing concern that Tanishq could not tap the wedding market while it continued to produce Westernized jewelry. Venkat explained, \"To the mainstream market, Tanishq's differentiation was based primarily on purity and quality. We needed a way to substantiate this claim. Under-karatage was an industry-wide problem and certifying gold purity in Tanishq's jewelry might help plant a seed of doubt in a family's bond with its family jeweler.\" Tanishq decided to pioneer the karatmeter, a machine that, in three minutes, measured the karatage of gold without destroying it, to certify the jewelry's purity at the point of sale. The press campaign confronted the underkaratage problem using bold, stark images (see Exhibit 7). Subsequent ads reinforced the quality of Tanishq, highlighting the stringent manufacturing process controls, and invoking the Tata tradition of trust (see Exhibit 8}. Walkin numbers shot up dramatically, and over 5,000 women checked their jewelry with over 60% finding their pieces to be under-karatage. By 2000, Tanishq had finally established a beachhead in the 22-karat gold jewelry market and had hit the Rs.100 crores mark as a brand. Going into plain gold jewelry brought new challenges. \"Selling plain gold jewelry moved us away from a marketing a brand to selling a commodity," Vincent Braganza, Tanishq head of marketing and merchandising explained. \"The plain gold consumer stood in the showroom and demanded, 'What is the gold price per gram that you are charging, and what are the making charges, and wastage?\" Since Tanishq's markup for gold was 15% to 25%, this created a conflict; local jewelers' mark-up was 5% to 15%, and even this varied widely from region to region. The customer was confused, "'Why do you have a much higher markup?" they would ask,\" Govind said. \"After some analysis, we realized that local jewelers were in fact overcharging because they were providing under-karatage jewelry." This period was a tough one for the firm. Tanishq's continued losses coupled with losses in their international watch initiative through 1999-2001 spelled trouble for Titan. To keep costs in check, a moratorium on television advertising was put in place, and other advertising expenditures were limited. Tanishq shifted to below the line promotions, and ran 360 launches at the stores that transformed the storefront into a thematic expression of the jewelry design (see Exhibit 9.) New research confirmed that the Tanishq name had positive associations, sounding modern and fancy, and suggested "good designs," but it continued to be perceived as exclusive, and out-ofreach. Among those who were aware but had not visited, Tanishq had "grand, historical designs like those put on by royalty," and offered the latest designs, but in a limited range, Among those who had visited, Tanishq was seen as modern, sophisticated, elegant, and artistic. The research also showed that consumers continued to rely on their long-standing relationship with their jewelers even if purity was questionable. Bhaskar explained, "The social embarrassment of having it revealed that your jewelry is not worth what you paid for makes one just sweep it all under the carpet, and continue with your jeweler to keep up appearances." Many consumers believed that all jewelers would \"more or less cheat on purity," yet accepted this, given other benets. (See Appendix B for additional information on 2000-2001 consumer information.) Based on the findings, Tanishq decided to run a campaign offering to test jewelry bought from other jewelers. Vincent explained: Unless you discredited the local jeweler and got credibility for yourself, there was no way you could actually justify the difference in the premium that you were charging to the consumer. We offered to test jewelry in the customer's presence, and then based on the purity of the gold in the jewelry; we would pay them a fair value. The karatmeter campaign worked well; \"It brought a lot of jewelry out into the open, it created a level of distrust around jewelers, and it got people into our stores," Venkat said. \"People saw they needn't fear when they walked into a Tanishq store." By early 2001, Tanishq's sales reached Rs.166 crores annualized. But Tanishq's struggles to maintain local brand presence continued. A Changing of the Guard In mid2001, with a management exodus leaving for a competitor, new management brought in from Titan implemented sweeping changes. A karigar park was set up to eliminate the traditional middleman and his margins. Tanishq now supplied the karigars with raw materials and had them follow its systems and procedures reducing gold inventories and improving jewelry quality. The move afforded a number of other efciencies including quick delivery, exibility to respond during exigency, reduced lead times and logistics costs. On the market front, Tanishq continued to offer designs for the wedding market and develop programs to increase traffic, running promotions, and advertising the karatmeter service and exchange scheme. At the same time, consumer spending habits began to change as well. Manoj noted, "From 1996- 2000, disposable income in India was quite low, with about 60% going to household expenses and 30% to 40% going to savings. By 2001, Indian consumers not only had more money for disposable items, they were willing to spend money on fashion items." \"Women didn't keep jewelry locked up anymore," he continued. \"They wanted different styles for different occasions. We were the only ones that could offer that range and we had to get that message out." Some managers felt that Tanishq had finally established itself as a premium Indian brand targeting the \"the modern Indian woman.\" The Collections sale in late 2001 played on the theme of getting existing and potential clients into stores. A story was attached to each collection, motivating thematic advertising, and inspiring curiosity. Inhouse designers produced the designs. Aria, for example, based on a closed setting, consciously played off an indigenous floral theme while making associations with a traditional seven stone design (see Exhibit 10). \"Collections were the turning point for us,\" Vincent said. \"We learned we had to tell new stories. We had to make a virtue of our own designsthe seven-stone concept, a traditional Indian design, was a breakthrough for us on that. It helped us overcome people's perception that we only offered Western designs." For collection launches, stores were converted into talking billboards, with signage transforming the store's entrance into something mysterious and spectacular. A red bag was introduced for customers to carry their purchases out; \"it wasn't quite Tiffany's blue box, but the Tanishq red bag became recognizable," Govind said. In 2002, Diva launched, offering pearls and diamonds in elegant design; Lightweights offered lighter weight, and therefore less expensive, fine gold jewelry for everyday wear. (Exhibit 11 shows the 2001-2002 Collections and advertising.) Advertising was still Western in theme and music and used models with \"not yet famous" faces (Exhibit 12 shows sample ads from 2003 collections). Moving Towards the Mainstream Jewelry Market: 2003-2005 In 2003, the team reassessed key barriers hindering the brand. \"Tanishq was an aspirational brand," Venkat said, \"but it still carried a perception of 'not for me.\" Tanishq was seen as operating in the studded, light, modern and western space. Further, Tanishq was perceived as expensiveh \"some thought we were at least twice as expensive as the local jeweler,\" Venkat explained: The brand retained perceptions of being cold and snobbish, and geared towards a self- centered, unwise spender. Research revealed that the target customer was a woman, at least 25 years old, college-educated, a good homemaker, socially versatile, smart spender and equally comfortable in both modern and traditional settings. The advertising for 2002-2003 aimed to communicate the moment of truth that happened in the stores. At the same time, a high-end exclusive jewelry collection was launched (Exhibit 13 shows sample ads from the campaign). Tanishq reached retail sales of Rs.416 crores in 2003-04. While brand awareness was high, translation to visits was low. Tanishq was still perceived as too expensive, unapproachable, with a low width and depth of product offerings. In 2004, Titan underwent a brand valuation exercise. Bhaskar explained. "We wanted to find out the reasons why consumers were coming into our stores to buy jewelry. Was it that they liked the store? Or, was it because they liked the brand? And if they liked the brand, what did they like about it? The answers were different across markets." (Exhibit 14 provides a comparison of 2001 and 2004 results.) The research showed that while Tanishq had been moving towards the regional jewelers, these competitors had also moved up the spectrum towards Tanishq. Several new collections were launched. Daytimes, a diamond-based collection, aimed to reposition diamonds as affordable, casual, young and contemporary; Colors, riding on a trend for colored jewelry, aimed to correct the perception that Tanishq only had modern designs (see Exhibit 15). Aarka, a high-fashion 22-karat gold collection aimed to position Tanishq's design and image leadership, was a joint venture with fashion designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee. Aamra, a collection of studded jewelry, attempted to tackle Tanishq's unapproachable image with a traditional studded collection inspired by the mango motif (see Exhibit 16). Wedding and festival collections were also launched (see Exhibit 17). The brand was associated in several high profile fashion events to integrate product design and communications efforts, including designing the Femina Miss India beauty pageant crown; and the Apsara Film Awards Trophy, as well as participating in Milan Fashion Week (see Exhibit 18). The results were spectacular with sales easily exceeding the ambitious target of R5550 crores and closing out at R5570 crores. In October 2005 a one-year exercise on the brand value proposition was completed. Unlike the previous studies that had focused on product features and demographic variables to segment the market, the new research study segmented the market into five psychographic segments: the confident matriarch, the sanction seeker, the balancer, the individualist and the uninvolved conformist (See Exhibits 19, 20 and Appendix C). Tanishq decided to go after the confident matriarch and the balancer, about 57% of the market. The resulting campaign captured \"a new tale of tradition,\" (see Exhibit 21). \"The evolving Indian woman has a new sense of self,\" Venkat explained: She believes in harmony, and in getting her way without rebelling. She plays by the rules to a large extent but modifies them in a way that suits her. She plays multiple roles, mother, daughter, wife, sister but is not defined by any one of her roles. She seeks acceptance and expression at the same time. She has a thorough grounding in tradition, and is proud of it. Tanishq had now positioned itself as a progressive Indian brand that combined tradition and heritage. Paheii, a major Hollywood fairytale, captured these themes, and Tanishq scored a coup by designing the jewelry for the film. A historical romance, the movie's main character was a progressive woman caught between the honor of her marriage to her husband and her love for a ghost. The film replicated the authentic Rajasthan style and incorporated period pieces in the actors' clothing and jewelry designed by Tanishq (see Exhibit 22). While the movie was not a hit, it was nominated for an Oscar; the Tanishq Paheli line, on the other hand, was a sell-out success. \"Going traditional was big for us,\" said Aanchal Jain, Tanishq marketing manager. \"Our move was to not only capture tradition, but make it new, modernize it.\" Tanishq's wedding designs for 2005 were designed to appeal to local tastes. Advertising was customized regionally in the local language and with local traditional costumes, and incorporated the Tata name (see Exhibit 23). The majority of the jewelry market was still bound in traditions with about 85% of the market (close to 42 million) identified as part of the "hardcore, original India.\" By 2006 Tanishq had 80 stores and its jewelry designs increasingly reected more traditional Indian patterns, designs and ethnic origins. But Tanishq stores still carried an elitist air. The GoldPlus Proposal [11 mid-2004, Mr. L. R. Natarajan (who went by LRN), VP of integrated supply chain management for Tanishq, proposed the company go after a segment that Tanishq was not serving. \"Tanishq has all along targeted a certain brand-conscious 'jewelry as adornment' consumer,\" LRN said. He continued: The semi-urban/ rural market is over Rs.36,000 crores. Furthermore, the traditional plain gold jewelry segment is around 80% of the overall market. This market segment only wants ethnic design plain gold jewelry at a competitive price. To serve this segment, we need to leverage our supply chain capabilities and compete on price. Impressed with the concept, Bhaskar decided to give LRN a shot at a pilot project by mid-2005. Two locations were selectedErode and Ratlam. Erode was LRNs hometown. Bhaskar selected Ratlam as the second test market since Ratlam jewelers had a reputation for providing accurate karatage and drew customers from distant towns. Franchisees paid the stores' xed cost: for the 2,000 square foot Erode store these were about R575 lakh; for Ratlam, about R338 lakh. Franchisees also incurred monthly operating costs, expected to be about R52 lakh in Erode and Rs.1.3 lakh in Ratlam. Store locations were selected where Tanishq did not have a presence. GoldPlus designed their 2,000 square-foot stores to resemble local competitors, "where the entire inventory is out on display, very much 'in your face,\" as LRN described. The team chose franchisees that were active in the local community. The Tata name was used aggressively in promotions and communications. The Gold Plus customer lived in a small town and wore jewelry for weddings and festivals. Her purchase was always a joint-decision, with a man involved. GoldPlus' advertising relied on a \"girl next door\" look (Exhibit 24 provides an example). At every turn the team looked for cost-effective ways to promote the brand name and the store. Several non-profit organizations were contacted, and deals were struck. "You talk about GoldPlus and bring customers to the showroom, and we'll give you a commission,\" LRN said. Couples were encouraged to hold their engagement party at the GoldPlus store. Pictures of the couple were printed onto banners hung over the store entrance and at the wedding ceremony (see Exhibit 25). "The couple and their families are proud to be associated with Tata," LRN added, \"Our objective is to connect with parents and build their confidence in us." In six months, the Erode store had done 52 marriages and broken even, with sales of about Rs.10 crores; Ratlam hit 125.3 crores in the same timeframe (see Exhibit 26 for results). Marketing expenses were about Rs. 50 lakhs across both stores. As LRN looked over the results, the Erode store had been protable, earning revenues of Rs.14.5 lakhs, an estimated 19% return on investment (see Exhibit 27). The plan involved rolling out to an additional nine towns, with total revenues projected at Rs.2,000 crores by 2010. The Dilemma The Tanishq team began their presentation with the following comment, "Last year's performance shows that we can play in both the highend market and the wedding jewelry market at the same time. It is only a matter of time before we win over the wedding jewelry market in the smaller towns as well. The consumer in these towns is rapidly evolving and beginning to resemble the consumer in the bigger cities and main urban centers. It has taken a long time but we are nally in a position to expand our footprint beyond just the major cities. Launching GoldPlus, at this point, will distract the rm, the customer and the channel. It will close the door for Tanishq to go after the plain gold wedding jewelry market. Unlike the watch business, a multi-brand strategy will not work in the jewelry market." \"GoldPlus has done well in Erode because they have put incredible attention to every detail," one Tanishq manager opined, "It will be very expensive to scale the effort that LRN has invested personally in Erode." Another manager worried: GoldPlus's positioning is based on the Tata name. The press will have a field day when they find this out. Once customers realize that that is also the core of the Tanishq proposition, it will cannibalize Tanishq's sales, especially when the GoldPlus stores are in close proximity to the Tanishq showrooms. Customers will drive from one town to another to get a price break. The fact that GoldPlus permits price negotiations further complicates matters. Customers will demand the same exibility in Tanishq as well. Yet another manager noted, "In the case of Tanishq, we have worked long and hard to make our brand different and unique. We have created the brand equity to be able to charge a premium price. We cannot build GoldPlus to the me level of distinctiveness. Also, for the upcoming year the government has passed an excise duty on branded jewelry. If GoldPlus becomes a network of over 20 stores, it too will be considered a brand and be taxed. The tax, Currently at 2%, will be projected to reach 6V0. Bhaskar also feared new entrants. Retailing was a hot sector in India with a large number of major business houses planning forays into this industry. A large local player could decide to compete nationally. Of greater concern was the scenario where jewelers from different regions would team up to gain a national footprint. Bhaskar and Venkat began their meeting to review the two plans. \"Tanishq is all about playing the high-end value game," Bhaskar concluded, "GoldPlus on the other hand is an out-andout low margin, volume play. Our watch business experience tells us that we can be effective at both ends. But is it the same case in the jewelry market?" Exhibit 1 Tanishq P&L Projection-5 Years (Rs. in crores) 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 Income from operations 121.92 278.24 453.84 655.96 880.99 Net Sales 114.61 262.24 427.75 618.24 830.34 Gross Contribution -1 17.19 39.34 64.17 92.73 124.56 Total Overhead 6.78 14.63 22.87 31.17 40.71 EBIT 8.29 19.87 33.41 50.15 68.53 Provision for Excise Duty 2.12 4.84 7.89 11.41 15.32 PBT 5.95 15.50 26.98 41.54 57.62 Net Capital Employed 19.61 33.63 47.64 61.65 75.64 ROCE 42.27% 59.08% 70.13% 81.35% 90.60% Source: Casewriter estimates. Select numbers have been disguised for confidentiality purposes. Note: Figures are comparable (incremental to Tanishq's existing sales and profits) if Tanishq were to go into GoldPlus territories, namely, smaller cities and rural areas. Assumptions: Tanishq would do 70% of what GoldPlus has planned to do considering the brand image and customer perception of Tanishq in the markets proposed. Tanishq would have a higher margin of 15% as against 11% that GoldPlus would get due to the markup and improved studded jewelry sales. As an established brand, Tanishq would spend probably one-third of GoldPlus' advertising spend. Tanishq would leverage its people strength and would incur only 60% of the employee costs proposed for GoldPlus. Capital employed remained the same although Tanishq had lower sales when compared to GoldPlus, considering the need to maintain variety to bring customers and revenues. Excise duty was considered for both brands, although GoldPlus did not pay excise duty in 2006. Unlike sales tax, excise duty was an indirect fixed rate ad valorem tax. Exhibit 2 GoldPlus P&L Projection-5 Years (Rs. in crores) 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 Income from operations 109.71 337.81 625.98 958.70 1,330.19 Net Sales 106.38 326.93 605.77 926.56 1,285.58 Gross contribution 11.18 34.00 61.80 96.22 132.97 Total overhead 6.87 19.57 33.90 48.38 65.00 EBIT 4.31 14.43 27.90 47.84 67.97 Provision for excise duty PBT 1.21 8.45 19.37 37.04 54.08 Net capital employed 23.08 46.56 66.42 83.93 102.25 ROCE 19% 31% 42% 57% 66% Source: Casewriter estimates. Select numbers have been disguised for confidentiality purposes. Assumptions as for Exhibit 1.Tanishq: Positioning to Capture the Indian Woman's Heart 507-025 Exhibit 3 Gold Consumption Trend in India 1990-2003 1200 1000 800 600 All figures in tons 400 200 0 1990 1991 1 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 0 2001 2002 2003 Year 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 New gold 178 157 264 241 298 386 411 645 691 654 680 681 695 709 Recycled gold 94 83 139 128 158 204 217 342 366 341 347 372 379 387 Total 272 240 403 369 456 590 628 987 1,057 995 1,027 1,053 1,074 1,096 Source: WGC Report, company documents.Exhibit 1431 Brand Perception Comparisons, 2001 to 2004: Price (ratings are relative to competition) Source: Company documents. Exhibit 14b Brand Perception Comparisons, 2001 to 2004: Design {ratings are relative to competition) Source: Company documents. Exhibit 19 Indian Jewelry Consumers Market Segmentation (2005) The Stable The Choosy Approval driven 10% The confident matriarch High Investment 37 driven 20% Display driven 5% The balancer 20% Wealth/Investment Orientation The Uninitiated The Adventurers Un involved conformist 8% Low Low High Wear/Adornment Orientation Source: Company documents. 24 Tanishq: Positioning to Capture the Indian Woman's Heart 507-025 Exhibit 20 Jewelry Market Segmentation (2005, all figures in %) Tanishq Competition Zone Town Segments Customer Customer N M E S Metro Small Town Confident Matriarch 38.0 37.2 39.6 16.9 11.4 60.5 37.6 37.0 24.4 18.8 18.4 22.9 33.4 12.7 20.0 19.5 Investment-Driven 20.1 38.0 9.7 24.1 13.1 Balance 16.8 10.7 17.5 3.1 9.9 10.9 Sanction Seeker 7.8 10.7 16.5 7.8 13.3 Uninvolved 9.6 7.2 4.6 12.9 22.2 0.5 4.7 12.3 Display-Driven 3.4 5.4 0.8 1.5 2.1 13.5 3.7 7.2 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 TOTAL 100.0 100.0 Source: Company documents. Note: Sanction seekers and approval driven are the same.Exhibit 26 GoldPlus Initial Results (March 2006) Erode Ratlam Budget Actual Budget Actual Store size, sq. feet 2,000 2,000 1,000 1,000 Avg. stock, Rs. crores 5.20 5.20 3.60 3.60 Ticket size, Rs. 8,000 13,749 7,000 17,080 Gold rate premium, %a 1.30 1.47 1.30 Avg. monthly sales, Rs. lakhs 115 160 56 50 Source: Casewriter estimates. Select numbers have been disguised for confidentiality purposes. Gold rate premium % is the mark-up on the purchase price of gold. Exhibit 27 Erode Franchisee Balance Statement (March 2006, in Rs. lakhs except sales) GoldPlus Sales in kg/year 230 Making charges 292 Franchisee margin 36.5 Franchisee's expenses 22 Net earnings of Franchisee 14.5 Franchisee investment 75 ROIC in Year 1 19% Source: Casewriter estimates. Select numbers have been disguised for confidentiality purposes.Appendix A Tanishq Consumer: 1998 Research Research identified several main purchase triggers and/ or occasions: when the price of gold fell or was discounted (usually January 1); at the onset of festival; for birthdays, anniversaries, and weddings; or any auspicious or religious occasion. Impulse purchases were limited typically to an overwhelmingly appealing design and occurred two to three times a year. Quality was the primary consideration; for consumers it was indicated by 22-karat, which carried the notion of purity with it. Look, finish, color, and craftsmanship all indicated quality. The jeweler was another factor considereda trusted individual with a good reputation that assured quality, service and discounts. Husbands gave no overt encouragement to the purchase, and often exhibited a resistance, and considered the purchase to be a dead investment. At the same time, they exhibited pride and admiration on seeing their wives wearing jewelry as it was reflective of their status. Typically, the husband preferred gold over other jewelry. The research revealed the major portion of jewelry ownership was through gifts during marriage, over 50% reported this. In some regions, however, consumers reported purchases of almost as much jewelry post-marriage as that gifted for marriage. Those purchasing jewelry were rarely alone, and even post-marriage purchasers were typically accompanied by a husband or elder. Amongst those who had visited Tanishq, the impetus to visit was prompted by a younger companion, word of mouth, curiosity and the showroom itself. Tanishq's designs were seen as a key positive: they were modern and attractive, especially to college girls, geometrical and light weight, delicate western styles, simple and elegant. Tanishq's \"traditional\" design offerings were also a strength. Some consumers were aware of Tanishq's 18-karat and 22-karat offerings. They were also aware of the assurance of the purity of the gold, and understood the pricing and exchange factors of resale value of gold, minus the making charges. Older visitors felt Tanishq was very costly, and found that bargaining was not possible. Younger visitors felt the premium price was justified by the exclusive designs. Those who visited but did not buy indicated that price was the primary barrier: \"With that amount we will get two items [elsewhere].\" However they did state their intention to purchase small itemsearrings, bangles, or a braceletin the future. Several mentioned that had not planned to purchase, others said the design of their choice was not available. Some reported perceptions of Tanishq as \"ethnic" and \"traditional Indian jewelry.\" They \"have an impression it will be Indian because Tatas are Indian.\" Those who had not visited Tanishq perceived the brand's design to be a strength. They indicated variety, that the brand was modern and trendy as well as traditional, that Tanishq offered something different, a stand out value, something unique. Other positives included Tanishq's Titan and Tata heritage which signaled trust. Tanishq's guarantees and buy-back facilities were additional positive factors. When asked why they had not visited the showrooms, several reasons came to light: the brand was for younger consumers, it was too expensive, and the showrooms evoked a feeling of distance and awe. Clientele were perceived to be of high society and \"not bothered about price,\" younger generationwho were attracted by the modern designs, \"people with taste,\" \"modern people,\" and models, actresses and industrialists. Source: Company documents. Appendix B Tanishq Consumer: 2000-2001 Research Results showed that consumers still had immense faith in their family jeweler; the concept of \"purity" was still a grey area, and many \"would rather go by their jeweler's assurance.\" Some implications around the purity issue included social embarrassment, loss of self-esteem, and insecurity, covering both rational and emotional elements. Quality led the factors at play in jewelry purchases, along with purity (22k24k) design (variety), weight (solidityas an anticipation of durability), craftsmanship (finish), and polish (i.e. shine). The key drivers in choice of jewelers included the traditional trust of a relationship built over years; assurance of the established family name including a guarantee and assurance of purity; a provider of core jewelry as part of a family legacy; the sheer range of jewelry on display providing a feast for the eyes. Many believed that all jewelers \"will more or less cheat on purity,\" and were willing to live with this as a compromise given other benefits such as credit or the ability to pay in installments, discounts, and gifts. Most would not recommend their jeweler to friends or in-laws however, \"unless I am 101 "/0 sure, which I am not.\" Perception of Tanishq among those who were aware of the brand but who had not visited a store was that the brand was "grand,\" with jewelry of historical design, \"like those put on by royalty.\" They perceived the stores to carry the latest in style and design, but with a limited range of product \"designer jewelry for those who believe in fashion.\" Those who visited perceived the brand to be modern, sophisticated, artistic, and elegant. Across both groups, Tanishq was perceived positively. The name \"sounds modern,\" \"seems very fancy, must be getting good designs there.\" The name specifically was \"short and sweet,\" and \"young girls who hear this name may be tempted.\" As one respondent noted, \"Tanishq means one type of gold which will be pure." lt carried connotations of sophistication and high society, \"a socialite in a Mercedes.\" However the research also noted considerable psychological distance, \"it is up there.\" Given Tanishq's brand status in 2001, a dual target group existed: the mother and the modern daughter. The mother continued to be traditional in her outlook towards jewelry. She was the biggest inuencer in the decision making and buying process. She was also the biggest barrier for Tanishq due to its \"non-serious" and \"ultra-premium\" imagery. The modern daughter was seen as the consumer who would pay a premium for the brand. Source: Company documents. Appendix C Tanishq Consumer: 2004-2005 Research There were four respondent profiles. The bride: a single woman, age 22-27 years, planning to get married in the next 6-12 months. The young mother: a married woman, age 28-35 years. The settled woman: married, age 36-45 years. The bride's mother: mothers, typically age 46-60 years, getting their daughters married in the next 6-12 months. The research identified four aspects to what women seek in jewelry in descending order of importance: self-actualization and self-expression; self esteem, perceived attraction, confidence; social affinity; and safety and well-being, affluence. Jewelry was seen as women's "personal\" wealth. It was perceived as "earnings\" for services provided to the family: \"My husband gives jewelry with love, he appreciates what I do for the family." Accumulating jewelry was perceived as a form of safety net and empowerment. It helped build relationships and consolidated the woman's position. Buying habits had changed little over the past few years. Jewelry was purchased with extreme caution and required a great deal of reassurance, especially if \"new\" choices were made. It helped a woman \"manage\" how she was perceived by the significant and not-sosignificant people in her social circle. Qualitative research distinguished five segments in of jewelry buying habits: the confident matriarch, the balancer, the sanction seeker, the individualist and the uninvolved conformist. Detailed quantitative research provided slightly different results and identified six segments: the confident matriarch, the balancer, the uninvolved conformist, the display driven or individualist, the approval driven (similar to the sanction seeker) and the investment driven. The confident matriarch, usually in her mid-30s or older, was typically in a nuclear family, or in a position of power in a joint family. She believed she had \"earned her due," and was therefore home- centric but not home bound. She often had strongly-held views, with firm convictions about dos and don'ts. She was however, open to new ideas; she realized the world has moved on and she needed to accept this. She had the confidence to adapt and to adopt change, and had the desire to be seen as progressive. She had considerable experience buying jewelry and had interacted extensively with the category, either by virtue of life-stage or due to very high involvement with jewelry. She did not typically lean on others and was often the inuencer for others in her family and friends' circle. While she had fairly strong rules about where to shop and what to buy in jewelry, she also had the confidence to experiment. The confident matriarch represented about 37% of the market. The sanction seeker was spread across all ages and life stages and was one of the most widespread segments in small towns. She was the archetypal \"tradition bound" Indian woman who was driven by social norms, expectations and constraints; she toed the line. She was not necessarily convinced about tradition or closed to change, however she lacked the inner will or confidence to go against the grain. She derived satisfaction from others' appreciation and had a high need for external validation. in terms of buying behavior, as a bride, the sanction seeker typically went along with her parents' choice of store for jewelry. She participated in selecting designs, with her mother's guidance. She might occasionally like something "different\" but was unlikely to insist on a design she liked if her mother did not approve. She believed her mother "knew better\" and wanted to do the "right" thing. As a married woman buying jewelry, she stuck to stores frequented by her mother. She shopped with her husband and sought her mother's and other family members' endorsement of design. She might experiment with stores recommended by friends if these are endorsed by her husband. By the time the sanction seeker bought jewelry as a bride's mother she had developed strong store loyalty, however this loyalty is based less on conviction and more on the fact that it is what she has \"always\" done, and was therefore more open to influence from her husband or significant others. The sanction seeker represented about 30% of the market; approval driven sanction seekers were about 10% and investment driven sanction seekers were about 20%. 32 Tanishq ease Goldplus decision: Supplement on market size . Estimated total market size for jewelry = Rs. 60, 000 Crore annually (page 2; also can be inferred from page 10) QB $15 billion (@Rs. 40 = $1). - Market size of investment-driven consumers = Rs. 48, 000 C (page 10) 98512 billion. - Market size for Goldplus = Rs. 36. 000 C (page 10) gm $9 billion. - Market size for Tanishq lSJ+PGJl = Rs. 24, 000 C QR $6 billion. - Market size for SJ only = R5. 12, 000 C Q $3 billion. - [Logic [f Rs. 48, 000 C is the total market for investment-driven consumers and Rs. 36, 000 C of this is in the rural areas, then it follows that Rs. 12, 000 C is in the urban areas to which Tanishq directs its PG}. Since the total urban market is Rs. 24, 000 C. it follows that the estimated market size for SJ is Rs. 12, 000 C.] In summary, il' Tanishq continues to chase the urban markets with SJ & PGJ, then it is after a market size of Rs. 24, 000 C ($6 bi) and if it chases SJ only, it is after a market size of Rs. 12, 000 C ($3 billion). Two observations: - Tanishq's revenue in 2004-2005 was Rs. 570 Crore ($142.5 million; page 9). Given the market size for SJ +PGJ in the urban areas to be Rs. 24, 000 C, this implies a market share of 2.38%. If we consider the market for S] only, it means a market share of 1.19 %, assuming 25% of the revenue in 2004-2005 came from SJ [Market share for S] = (25% of Rs. 570 C)! (Rs. 12, 000 C) x 100]. - These are not high numbers for market share at all, especially for SJ, and hence mean that there is plenty of room to grow in the urban markets especially given the pioneering status Tanishq enjoys for SJ and to some extent for PGJ given their hybrid designs. In other words, there is plenty of incentive for them to stick to the urban markets with SJ & PGJ. - According to Bhat, the company's goal was to reach a revenue of Rs. 5, 000 C ($1.25 bi) by 2010 (top of Page 2). This represents a market share of 21% for the urban markets. Ambitious, perhaps, but they would be chasing a high market share in the rural areas also. Let's see why. The pilot tests show that the entire rural market does not promise success, but only a portion does. From the pilot tests, if we assume that 50% of the rural markets have promise for Goldplus's success, then the effective market they are chasing is Rs. 18, 000 C (=50% of the Rs. 36, 000 C rural market). Assuming they hope to earn Rs. 4, 000 C of their Rs. 5, 000 C goal from the rural markets, this would mean a market share of 22.2% - not trivial, especially given the erce competition they would face in those markets (e.g., the case mentions that many regional jewelers were re-organizing to battle national jewelry brands). If they can achieve 22.2% market share in the urban markets, they could eam Rs. 5, 326 Crore (=22.2% of Rs. 24, 000), i.e., more than their target of $5, 000 C. Given that Tanishq had a strong foothold in the urban markets whereas the rural markets characterized a red ocean where regional jewelers were reorganizing to compete with national chains, achieving a 22.2% market share is more likely in the urban markets and on top of that it promises higher retumS- [Anahematiammkhmamusi they ned an urban market share of 21% but a rural market share of 22.2% to achieve their target of Rs. 5, 000 C]. - 91:11am: Tanishq would be better off chasing the urban markets than the rural markets