Question: give a summary of this article please!!! comment on its implications for manager rewards and investors returns. please answer I really need for class!!!! thank

give a summary of this article please!!! comment on its implications for manager rewards and investors returns. please answer I really need for class!!!! thank you!!!!

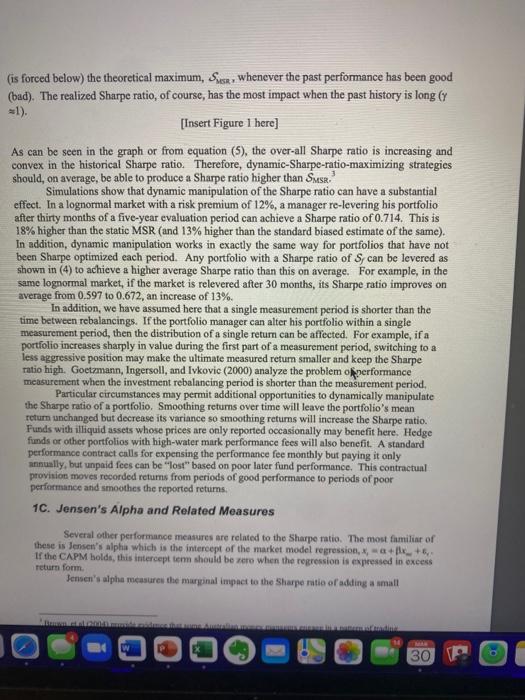

Portfolio Performance Manipulation and Manipulation-Proof Performance Measures Abstract Over the years numerous portfolio performance measures have been proposed. In general they are designod to capture some particular enhancement that might result from active management. However, if a principal uses a measure to judge an agent, then the agent has an incentive to game the measure. Our peper shows thait such gaming can have a substantial impact on a number of popular measures even in the presence of extremely high transactions costs. The question then arises as to whether or not there exists a measure that eannot be gamed? As this paper shows there are conditions under which such a measure exists and fully chancterizes it. This manipulation-proof measure looks like the average of a power utility function, calculated over the return history. The case for using our alternative ranking metric is particularly compelling in the hedge fund industry, in which the use of derivatives is unconstrained and masager compensation itself induces a non-linear payoff and thas ettcourages gaming. Manipulation-Proof Performance Measures Fund managers naturally claim that they can provide superior performance. Investors must somehow verify these claims and discriminate among managers. In 1966, William Sharpe, using mean-variance theory, introduced the Sharpe ratio to do this in a quantifiable fashion. Together with its close analogues, the information ratio, the squared Sharpe ratio and M-squared, the Sharpe ratio is now widely used to rank investment managers and to evaluate the attractiveness of investment strategies in general. Other measures such as Jensen's alpha and the Henriksson-Merton market timing measure, although they evaluate other aspects of performance are also based on the same or similar theories. If investors use performance measures to reward money managers, then money managers bave in obvious incentive to manipulate their performance scores. Our paper contributes in two ways to this literature. First, it points out the vulnerability of traditional measures to a number of simple dynamic manipulation strategies. Second, it offers a formal definition of the properties that a manipalation-proof measure should have and derives such a measure. For a measure to be manipulation proof, it must not reward information free trading. In this regard the existing set of measures suffer from two weaknesses. First, most were designed to be used in a world where asset and hence portfolio retums have "nice" distributions like the normal or lognormal. But, this ignores the fact that managers can potentially use derivatives (or trading strategies) to radically twist return distributions. Hedge fund returns, in particular, have distributions that can deviate substantially from normality, and the hedge fund industry is one in which performance measures like the Sharpe ratio are most commonly employed. Second, "exact" performance measures can be calculated only in theoretical studies (e.g., Leland (1999) and Ferson and Siegel (2001)); in general, they must be estimated S Since standard statistieal techniques are designed for independent and identically distributed variables, it is possible to manipulate the existing measures by using dynamie strategies resulting in portfolios whose returms are not so distributed. We show here that portfolios using dynamie strategies investing in index puts and calls can be used to manipulate the common portfolio measures. This is true even when only very liquid options are used and when transactions costs are extremely large. Numerical results are presented for the Sharpe ratio, Jensen's alpha, Treynor ratio, Appraisal ratio, generalized alpha, Sortibo ratio (1991). Van der Meer, Plantinga and Forsey (1999) ratio, and the timing measures of Henriksson and Merton (1991), and Treynor and Mazuy (1966). In every case, the manipulations presented generate statistically and economically significant "better" portfolio scores even though all of the simulated trades can be carried out by an uninformed investor. The paper describes general strategies for manipulating a performance measure. (1) Static manipulation of the underlying distribution to influence the measure. Such strategies can enhance scores even if the evaluator calculates the measure without any estimation error whatsoever. (2) Dynamie manipulation that induces time variation into the return distribution in order to influence measures that assume stationarity. This can enhanee a portfolio's score even if the measure is calculated without any "estimation errot" but without regard to the (unobservable) time variation in the portfolio's return distribution. (3) Dynamic manipulation strategies that focus oa indueing estimation error. Since measures have to be entimated with real world data, there are atrategies that can induce positive biaves in the resulting values. As a simple exaniple, imagine an evaluator who estimates a fund's Sharpe ratio by calculating its excess return's standard deviation and average excess return over a 36 month period using monthly data. Further assume the fund manager simply wishes to maximize the expected value of the calculated Sharpe ratio. A simple strategy that accomplishes this has the fund sell an out of the money option in the first month, while investing the remaining funds in the risk free asset. If the option expires worthless the portfolio is then invested wholly in the risk free asset for the remaining 35 months. Whenever this happens the portfolio has a zero standard deviation, a positive excess return, and thus an infinite Sharpe ratio. Since there is a strictly positive probability that the option will expire worthless the expected value of the calculated Sharpe ratio must be infinity. Worse yet, as the paper shows even with goals other than maximizing the expected calculated performance value, and concern for other moments of the test statistic a manager can deliberately induce large economically significant measurement errors to his advantage. Also notice that increasing the frequency with which retums are observed does not shield the set of existing measures from this type of dynamic manipulation. If the set of current measures are vulnerable to manipulation the question naturally arises as to whether a manipulation proof measure exists. To answer this question, one first needs to determine what "manipulation proof" means. This paper defines a manipulation proof performance measure (MPPM) as one that has three properties: 1. The score's value should not depend upon the portfolio's dollar value. 2. An uninformed investor cannot expect to enhance his estimated score by deviating from the benchmark portfolio. At the same time informed investors should be able to produce higher scoring portiolios and can always do so by taking advantage of arbitrage opportunities. 3. The measure should be consistent with standard financial market equilibrium conditions. It tums out that these three requirements are enough to pin down the measure. The first simply implies that returns are sufficient statistics rather than dollar gains or losses. The sccond and thind, however, provide a great deal more structure. As the earlier diseussion indicates there are several ways to manipulate a performance measure and the second condition implies that a MPPM must be immune to all of them. In particular that means the manager cannot expect to benefit by trying to alter the score's estimation based upon observable data. To accomplish this goal the score must be (1) increasing in returns (to recognize arbitrage opportunities), (2) concave (to avoid increasing the score via simple leverage or adding unpriced risk), (3) time separable to prevent dynamic manipulation of the estimated statistic, and (4) have a power form to be consistent with an economic equilibrium. The resulting measure () suggested here is =(1)At1ln(T1i=1T[(1+rA)1(1+rh+xi)]). The coefticient can be theught of as the evaluator's "risk aversion" und should be selected to nake bolding the benchmark optimal for an uninformed manager. The variable At is the length of time between observations while T equals the total number of observationa. These two variables ( (At and J simply help normalize the measure's final calculation. The portototo's refum at time t is xn and the riak free asse's retum is r. Note the measure is casy to calculate and has an intuitive interpretation as the average per period welfare of a power utility investor in the portfolio over the time period in question. As an example, consider a fund with returms of -1 , 05,.17, and -.02 . Assume the risk free rate is .01 . In this case T=4,rF is .01 , and if equals 2 Our paper was originally motivated by the question of whether the existing set of performance measures is sufficiently manipulation proof for practical use. This is particularly relevant in the presence of transactions costs, which may offset whatever "performance" gains a manager might hope to generate from trading for the purpose of manipulating the measure. Therefore, our paper explores how difficult it is to meaningfully game the existing measures. For the seven measures examined here - four ratios (Sharpe (1966), Sortino (1991), Leland (1999), and Van der Meer, Plantinga, and Forsey (1999)), and three regression intercepts (the CAPM alpha, Treynor and Mazuy (1966), and Henriksson and Merton (1981)) - the answer is not encouraging. Simple dynamic strategies that only relever the portfolio each measurement period or buy (very liquid) at the money options can produce seemingly spectacular results, even in the presence of very high transactions costs. For example, consider the Henriksson and Merton (1981) measure. A simple options trading scheme in the presence of transactions casts equal to 20% produces "very good" results. The final regression statisties report that the portfolio has returns that are superior to the market's nearly 65% of the time, and (using a 5% critical value) statistically significantly better 9% of the time. Obviously, lower and more realistic transactions costs only make matters worse. The other measures analyzed here are similarly susceptible to having their estimated values gamed. Our results have a number of implications for investment management. Hedge funds and other altemative investment vehicles have broad latitude to invest in a range of instruments, including derivatives. Mitchell and Pulvino (2001) document that merger arbitrage, a common hedge find strategy, generates returns that resemble a short put-shigrt call payoff. Recent research by Agarawal and Naik (2001) shows that hedge fund managers in general follow a number of different styles that are nonlinear in the retums to relevant indices. In a manner - similar to Henriksson and Merton, Agarawal and Naik use option-like payoffs as regressors to capture these non-linearities. In fact, option-like payoffs are inherent in the compensationstructure of the typical hedge fund contrict. Goetmann, Ingersoll and Ross (2001) show that the high water mark contract, the most common type in the hedge fund industry, effectively leaves the investor short 20% of a call option. The call is at-the-moncy cach time it is "reset" by a payment and out-of-the money otherwise. The paper is structured as follows. Section 1 discusses various ways in which the Sharpe ratio can be manipulated. Section 2 discusses the manipulation of a number of other measures including those using reward to variability (Section 2A ) and the Henriksson-Merton and Treynor-Meny market timing measures (Section 2B). Section 3 derives the manipulation proof performance measure, and Section 4 concludes: 1. Manipulation of the Sharpe Ratio Although the Sharpe ratio is known to be subject to manipulation, if remains one of if not the moot widely used and cited performance measures. If, therefore, makes a good example to introduce performance manipulation in mere detail. Other neasures are examined in the next section. 1A. Static Analysis A number of papers have shown that by altering the distribution function governing returns the statistical mean and variance can be manipulated to increase the Sharpe ratio to some degree. Ferson and Siegel (2001) look at a fairly general case (that includes potentially private information) while Lhabitant (2000) shows how using just a couple of options can generate seemingly impressive values. Since the focus of this paper is on dynamic strategies and the development of a MPPM to prevent all sources of manipulation the only static result presented here is the characterization of the retum distribution that maximizes the Sharpe ratio. Readers interested in additional details should consult one of the above cited articles. The Appendix shows that Sharpe ratio maximizing portfolio in a complete market is characterized by a state i return in excess of the interest rate (xi1/3) of xiNSi=xLes[1+SMsh21p^i/pi] Here Ssin=[p^i2/pi1]1/2 is the maximum possible Sharpe ratio, and pi and p^i are the true and risk-neutral probabilities of state i. Since the Sharpe ratio is invariant to leverage, we are free to specify the portfolio's mean excess return, xmas, at any level desired. While the MSR has a number of interesting properties it is also true that one way to mitigate its impact on a fund's apparent performance is to sample returns more frequently. As one does 50 the percentage difference between the market portfoliq''s Sharpe ratio and that of the MSR goes to zero. However, as will be seen below frequent samyting does not help when managers use dynamic manipulation strategies and thus the paper now turns to this issue. 1B. Dynamic Analysis Calculated values of the Sharpe ratio and virtually all other performance measures use statisties based on the assumption that the reported retums are independent and identically distributed. While this may be a good deseription of typical portfolio returns in an efficient market, it clearly can be violated if a portfolio's holdings are varied dynamically depending on its performance. Consider a money manager who has been lucky or unlucky with an average realized return high or low relative to the portfolio's realized variance. The retum distribution in the future will likely not be similar to the experience. Consequently, to maximize the Sharpe ratio, the portfolio can be modified to take into account the difference in the distributions between the realized and future returns just as if the returns distribution was not ex ante identically distributed each period. This dynamie manipulation makes the past and future returns dependent when computed by an unconditional measure. To illustrate, suppose the manager has thus far achieved an historical average excess return of ik, with a standard deviation of ok. The portfolio's average excess returm and atandard deviation is the future are denoted by x, and f. Then is meavured Sharpe ratio over the cobire period will be will be S=(xk2+h2)+(1)(xf2+f2)[xk+(1)xf]2xi+(1)xf=xi2(1+1/Sh2)+(1)xf2(1+1/Sf2)[xh+(1)xf]2xk+(1)xf where y is the fraction of the total time period that has already passed, and a and f are the past and future Sharpe ratios. By inspection, the overall Sharpe ratio is maximized by holding in the future a portfolio that maximizes the future Sharpe ratio, Sf=SMosn.. However, regardless of what Sharpe ratio can be achieved in the future, leverage is no longer irrelevant as it was in the static case. Maximizing the Sharpe ratio in (3), we see that the optimal leverage gives a target mean excess return of xf={xk(1+Sk2)/(1+Sf2)forxk>0forxh0 If the manager has been lucky in the past and achieved a higher than anticipated Sharpe ratio, Sh>Sf, then the portfolio should be targeted in the future at a lower mean excess return (and lower variance) than it has realized. This allows the past good fortune to weigh more beavily in the overall measure. 1 Conversely, if the manager has by en unlucky and Sk0forSh0. Figure 1 plots the overall Sharpe ratio as a function of the realized historical Sharpe ratio for histories of different durations. The overall Sharpe ratio can, on average, be maintained above 'For a fixed Sharpe naio, the overal mean is linear in the futuro leverse white the overall standand deviation is convex. The proportional thanges in the mean and candert devietice with reppect to future loversece are equal when the farture and historical Sharpe ration are equal. Therefore, when the hisarical Shape natio is lew than the future Stape rato, ircteating leverage incteaes the overall mean at a fater rate than the standand deviatice and viee vera. 2 Becaine the optimal furure levenge is infinile when x30. the past Sharpe ratio does not affect the overall sharpe ratio, and the value of the oyerals Sharpe natio for SA0 Clearly, alpha is subject to severe manipulation. A MSRP can be created with any desired leverage, so its alpha can in theory be made as large as desired by levering. The Treynor (1965) ratio and the Treynor appraisal ratio were introduced in part to avoid the leverage problem inherent in alpha. The Treynor measure is the ratio of alpha to beta 6 while the appraisal measure is the ratio of alpha to residual standard deviation. Like the Sharpe measure, and unlike alpha, the two Treynor measures are unaffected by leverage. Both Treynor measures indicate superior performance for the MSRP. The MSRP's two Treynor ratios are? TMSA=MSAMSA=(SMSA2/Smi121)xmi1>0AMSA=Var[xMaiMSAxmai]MSA=SMSA2Smi2>0. Any MSRP has the largest possible Treynor appraisal ratio, but Treynor ratios in excess of the MSRP's can be achieved by forming portfolios with positive alphas and betas close to zero.' In addition, since the Sharpe ratio is subject to dynamic manipulation, alpha and both "If arset i is combined with the market intn a portfolio wx,(1w)x2, then (S/w)1,/ma. "The brea of the maximal-Sharpe-ratio ponfolio, Inse, is whese 5 . in the Sharpe ratio of the market. The thind equality follows since the MSRP is meab-variance efficient "Treytoo's (695s) ceiginal definition of his meanure was r,/; however, / is now the commonly acopeed derifition. Thepter Apraisel rale, we ate 4 and positive alpha. Therefire, its Thereer natio will be ta: Treynor measures are as well and can be increased above these statically achieved values. The manipulation is illustrated in Figure 2. If returns have been above (below) average, then decreasing (increasing) the leverage in the future, will generate a market line for the portfolio with a positive alpha. Not surprisingly, this is very similar to the dynamic manipulation that produces a superior Sharpe ratio - leverage is decreased (increased) after good (bad) returns. [Insert Figure 2 here] Alpha-like measures can also be computed from models other than the CAPM. Under quite general conditions, the generalized alpha of an asset or portfolio in a single-period model is pm=n=xpBpxmwhereBp=Cov[u(1+rf+xm),xm]Cov[u(1+rf+xm),xx] Br is a generalized measure of systematic risk, rr is the per-period (not-annualized) interest rate, and u() is the utility function of the representative investor holding the market. The systematic risk coefficient, B, can be estimated by regressing x on xm using u() as an instrumental variable. Ingersoll (1987) and Leland (1999) suggest using a power utility funetion where u(1+rf+xm)=(1+rf+xm)with=Var[n(1+rf+xm)]n[E(1+rf+xm)]ln(1+rf). This generalized alpha gives a correct measure of mispricing assuming that the representative utility function is correctly matched to the market portfolio; that is, if the market portfolio does maximize the utility function employed. But this statement, tautological as it is, only applies to single-period or static manipulation. Even if the utility is correctly matched to the market, strategically rebalancing the portfolio over time can give an apparent positive alpha due to the deviation between the average and a properly conditioned expectation. The basic technique is the same - decrease (increase) leverage after good (bad) returns. Beyond the single-factor CAPM, there are several alpha-like performance measures in use. These models augment the single factor CAPM model with additional risk factors such as the Fama-French factors. However, within the simulations discussed in the next sub-section, no such factors exist. The market returns are generated in an environment where (8) with amen=0 is the correct way to price. This single factor model should do at least as well in the simulated environment as any model with additional, but within the simulation, unpriced, factors. Similarly, if a multi-factor model were simulated, a multi-dimensional rebalancing of the portfolio should produce positive alphas. For this reason, the Chen and Knez (1996) measure and similar measures have not been examined. 1D. Manipulating the Sharpe Ratio and Alpha with Transactions Costs In practice, a manager can change a portfolio's characteristies far more frequently than once during the typical measurement period. On the other hand, the costs of transacting may "Set Inpendit (1987) for the dervition of this aeneal manue of cyutematic riak eliminate the apparent advantage of many manipulation strategies. As we show below even very high transaction costs cannot prevent managers from manipulating the Sharpe ratio or other performance measures. Determining the optimal dynamic manipulation strategies for all of the popular performance measures is beyond the scope of our paper. The optimal manipulation strategy depends on the size of the transaction costs, the complete set of returns to date within the evaluation period, the distribution of future returns, and the number of periods remaining in the evaluation period. However, for our purposes, an optimal strategy is not necessary. We only want to establish whether reasonably simple trading strategies can distort the existing measures even in the presence of transactions costs, and if so, by bow much. [Insert Table I here] Table I shows the Sharpe ratio performance of a dynamically rebalanced portfolio. The portfolio is always invested 100% in the market with leverage; no derivatives are used to alter the distribution. The leverage starts at one. After the first year, the portfolio is levered at the beginning of each month so that the target mean is given by equation (4) though the leverage is also constrained to be between 0.5 and 1.5 so the portfolio will not be too extreme in nature. The levenge is achieved by buying or selling a synthetic forward contract consisting of a long position in calls and a short position in puts that are at-the-money in present value i.e., the strike price per dollar invested in the market is eett. Trades in these two options are assessed a roundtrip transaction cost of 0%,10%, or 20%. The simulation consisted of 10,000 repetitions. On average the dynamically-manipulated portfolio's Sharpe ratio is 13% higher than the market's and 7% higher than the MSRP's. In the 10,000 trials, the manipulated portfolio had a Sharpe ratio higher than the market's 82.6% of the time in the absence of transactions costs. 10 Even with a 20% round-trip transactions cost, the dynamically-manipulated portfolio still beat the market almost three-quarters of the time. It should be mentioned here that comparing these winning percentages to 50% is a conservative test of how good the manipulated Sharpe ratio is. The CAPM predicts that any portfolio's Sharpe cannot be bigger than the market's - not that it will be bigger or smaller with some measurement error. The Sharpe-manipulated portfolio beats the market frequently, but is it substantially better statistieally; that is, is the difference in the Sharpe ratios significant? In practice this question is seldom asked becuuse Sharpe ratios are at least as difficult to estimate precisely as are mean retums." However, differences between two Sharpe ratios can be more precisely estimated "The frequency with which one portiolio beuts another mast be interpeeted with cmution when the "winning" portiobio bolde derivativea. To illuatrate, consider two porffotion that are almout identical. The only difference in the sesond porifolio sells derivitive awets that bave a poitive payoff only rarely, like docp out-of the money optiona. The procecds are ievested in bonde. Wheneve, the payoff event for the derivative does not occur, then the accend tor the secend porfolole by sinsset any perfonance measure, Since the payoff eveat can be made a rate as decirod obly the levsrege is disnged so bey are not aubject to this probles if the underlying returns are correlated as would generally be true and is certainly true in our example. Statistical tests of portfolio retums generally assume that the returns are independent and identically distributed over time. Such is not the case here for the manipulated portfolio which makes deriving the distribution of the difference in the Sharpe ratios a difficult task. Furthermore, there is little point in doing so as our simulation is a constructed example, and the statistic we derive would be applicable only to that case. Fortunately we need not do so. Our simulations give us a sample distribution of the differences, so we can easily determine how often the difference is k standard deviations above or below zero. For example, with no transactions costs, the difference between the manipulated Sharpe ratio and the market Sharpe ratio was more than 1.65 standard deviations above zero 20.4% of the time. It was never more than 1.65 standard deviations below zero. Were the difference normally distributed, each of these should have occurred 5% of the time. Of course, the differences between the Sharpe ratios is not normal, but this is still evidence that a properly constructed test would conclude that the difference was significant more often than chance would prescribe if the true expected difference were zero. Table I gives the percentages of times that the Sharpe ratio difference exceeds 1.65 standard deviations. Using Jensen's alpha or one of the Treynor measures to evaluate performance gives even "better" results. The dynamic portfolio has an average annualized alpha over 2% and the alpha is positive more than 92% of the time in the absence of transactions costs. Even with 20% round-trip costs, the average alpha is still 1.6% and is positive over 85% of the time. The generalized alpha shows only slightly weaker performance for the manipulated portfolio. In the simulations we had the luxury of knowing the correct utility function, but superior performance as measured by the generalized alpha is insensitive to risk aversion assumed. Similar superior performance was found for risk aversions throughout the range 2 to 4. It is not surprising that the alphas can be manipulated more easily than the Sharpe ratios. The CAPM null hypothesis is that =0. With measurement error positive and negative deviations are aprle ximately equally likely. However, the CAPM null hypothesis on the Sharpe ratio is that it is less than the market's. The manipulation on the Sharpe ratio has to first make up this difference before beating it. 2. Manipulating Other Measures 2A. Reward-to-Variability Measures Many other performance measures have been proposed over the years to correct perveived flaws in the Sharpe natio or to extend or modify its mentsurement. Some of these measures use a benchmark portfolio - usually some market index. All of them are subject to the same type of manipulation that can be used on the Sharpe ratio. In this and the nexi sections we examine many of the more popular alternatives. Modigliani and Modigliani's (1997) M-squared score is nimply a restatement of the Sharpe ratio. The M-squared measure is the expected excess retum that would be eamed on a portsolio if it were levered so that its standard deviation was equal to that on the benchmark. Clearly maximizing the Sharpe rabio also maximizes the M-aquared measure relative to any benchenark. Therefore, it is also subject to the same manipulation. Sharpe's information rutio is another sinsple variation on the oniginal Sharpe ratio. The difference is that the excess returns are calculated relative to a risky benchmark portfolio rather than the risk-free rate. If x and xb are the excess returns on the portfolio and the benchmark, the information ratio is Siobrutain=Var(xxb)xx3 Since excess returns are the returns on zero net cost (or arbitrage) portfolios, they can be combined simply by adding them together without any weighting. Clearly the arbitrage portfolio that is a combination of the excess returns x~ and x~b has an information ratio with respect to the benchmark, x~b, numerically equal to the Sharpe ratio of x~ alone; therefore, the information ratio is subject to the same manipulation as the Sharpe ratio. In particular, adding the MSRP excess returns to the market portfolio will achieve the highest possible information ratio relative to the market. One criticism commonly leveled against the Sharpe ratio is that very high returns are penalized because they increase the standard deviation more than the average. This is the reason the MSRP has bounded returns. To overcome this problem, it has been suggested to measure risk using only "bad" returns. In particular, Sortino (1991) and others have measured risk as the root-mean-square deviation below some minimum acceptable return. Van der Meer, Plantinga and Forsey (1999) have further suggested that the "reward" in the numerator should only count "good" retums. Sortino's downside-risk and van der Meer, Plantinga and Forsey's upsidepotential Sharpe-like measures are The minimal acceptable excess retum, x, is commonly chosen to be zero. 12 While these two measures do avoid the problem inherent in the Sharpe ratio of penalizing very good outcomes, they do this too well so that the highest possible retums are sought in licu of all others. As shown in the Appendix, the Sortino downside-risk and VPF upside-potential maximizing portfolios are very similar. They both hold the MSRP, an extra very large investment in the state security for the state with the highest market return (the lowest likelihood ratio p^2(p2p1/pi), and bonds. Portfolio Performance Manipulation and Manipulation-Proof Performance Measures Abstract Over the years numerous portfolio performance measures have been proposed. In general they are designod to capture some particular enhancement that might result from active management. However, if a principal uses a measure to judge an agent, then the agent has an incentive to game the measure. Our peper shows thait such gaming can have a substantial impact on a number of popular measures even in the presence of extremely high transactions costs. The question then arises as to whether or not there exists a measure that eannot be gamed? As this paper shows there are conditions under which such a measure exists and fully chancterizes it. This manipulation-proof measure looks like the average of a power utility function, calculated over the return history. The case for using our alternative ranking metric is particularly compelling in the hedge fund industry, in which the use of derivatives is unconstrained and masager compensation itself induces a non-linear payoff and thas ettcourages gaming. Manipulation-Proof Performance Measures Fund managers naturally claim that they can provide superior performance. Investors must somehow verify these claims and discriminate among managers. In 1966, William Sharpe, using mean-variance theory, introduced the Sharpe ratio to do this in a quantifiable fashion. Together with its close analogues, the information ratio, the squared Sharpe ratio and M-squared, the Sharpe ratio is now widely used to rank investment managers and to evaluate the attractiveness of investment strategies in general. Other measures such as Jensen's alpha and the Henriksson-Merton market timing measure, although they evaluate other aspects of performance are also based on the same or similar theories. If investors use performance measures to reward money managers, then money managers bave in obvious incentive to manipulate their performance scores. Our paper contributes in two ways to this literature. First, it points out the vulnerability of traditional measures to a number of simple dynamic manipulation strategies. Second, it offers a formal definition of the properties that a manipalation-proof measure should have and derives such a measure. For a measure to be manipulation proof, it must not reward information free trading. In this regard the existing set of measures suffer from two weaknesses. First, most were designed to be used in a world where asset and hence portfolio retums have "nice" distributions like the normal or lognormal. But, this ignores the fact that managers can potentially use derivatives (or trading strategies) to radically twist return distributions. Hedge fund returns, in particular, have distributions that can deviate substantially from normality, and the hedge fund industry is one in which performance measures like the Sharpe ratio are most commonly employed. Second, "exact" performance measures can be calculated only in theoretical studies (e.g., Leland (1999) and Ferson and Siegel (2001)); in general, they must be estimated S Since standard statistieal techniques are designed for independent and identically distributed variables, it is possible to manipulate the existing measures by using dynamie strategies resulting in portfolios whose returms are not so distributed. We show here that portfolios using dynamie strategies investing in index puts and calls can be used to manipulate the common portfolio measures. This is true even when only very liquid options are used and when transactions costs are extremely large. Numerical results are presented for the Sharpe ratio, Jensen's alpha, Treynor ratio, Appraisal ratio, generalized alpha, Sortibo ratio (1991). Van der Meer, Plantinga and Forsey (1999) ratio, and the timing measures of Henriksson and Merton (1991), and Treynor and Mazuy (1966). In every case, the manipulations presented generate statistically and economically significant "better" portfolio scores even though all of the simulated trades can be carried out by an uninformed investor. The paper describes general strategies for manipulating a performance measure. (1) Static manipulation of the underlying distribution to influence the measure. Such strategies can enhance scores even if the evaluator calculates the measure without any estimation error whatsoever. (2) Dynamie manipulation that induces time variation into the return distribution in order to influence measures that assume stationarity. This can enhanee a portfolio's score even if the measure is calculated without any "estimation errot" but without regard to the (unobservable) time variation in the portfolio's return distribution. (3) Dynamic manipulation strategies that focus oa indueing estimation error. Since measures have to be entimated with real world data, there are atrategies that can induce positive biaves in the resulting values. As a simple exaniple, imagine an evaluator who estimates a fund's Sharpe ratio by calculating its excess return's standard deviation and average excess return over a 36 month period using monthly data. Further assume the fund manager simply wishes to maximize the expected value of the calculated Sharpe ratio. A simple strategy that accomplishes this has the fund sell an out of the money option in the first month, while investing the remaining funds in the risk free asset. If the option expires worthless the portfolio is then invested wholly in the risk free asset for the remaining 35 months. Whenever this happens the portfolio has a zero standard deviation, a positive excess return, and thus an infinite Sharpe ratio. Since there is a strictly positive probability that the option will expire worthless the expected value of the calculated Sharpe ratio must be infinity. Worse yet, as the paper shows even with goals other than maximizing the expected calculated performance value, and concern for other moments of the test statistic a manager can deliberately induce large economically significant measurement errors to his advantage. Also notice that increasing the frequency with which retums are observed does not shield the set of existing measures from this type of dynamic manipulation. If the set of current measures are vulnerable to manipulation the question naturally arises as to whether a manipulation proof measure exists. To answer this question, one first needs to determine what "manipulation proof" means. This paper defines a manipulation proof performance measure (MPPM) as one that has three properties: 1. The score's value should not depend upon the portfolio's dollar value. 2. An uninformed investor cannot expect to enhance his estimated score by deviating from the benchmark portfolio. At the same time informed investors should be able to produce higher scoring portiolios and can always do so by taking advantage of arbitrage opportunities. 3. The measure should be consistent with standard financial market equilibrium conditions. It tums out that these three requirements are enough to pin down the measure. The first simply implies that returns are sufficient statistics rather than dollar gains or losses. The sccond and thind, however, provide a great deal more structure. As the earlier diseussion indicates there are several ways to manipulate a performance measure and the second condition implies that a MPPM must be immune to all of them. In particular that means the manager cannot expect to benefit by trying to alter the score's estimation based upon observable data. To accomplish this goal the score must be (1) increasing in returns (to recognize arbitrage opportunities), (2) concave (to avoid increasing the score via simple leverage or adding unpriced risk), (3) time separable to prevent dynamic manipulation of the estimated statistic, and (4) have a power form to be consistent with an economic equilibrium. The resulting measure () suggested here is =(1)At1ln(T1i=1T[(1+rA)1(1+rh+xi)]). The coefticient can be theught of as the evaluator's "risk aversion" und should be selected to nake bolding the benchmark optimal for an uninformed manager. The variable At is the length of time between observations while T equals the total number of observationa. These two variables ( (At and J simply help normalize the measure's final calculation. The portototo's refum at time t is xn and the riak free asse's retum is r. Note the measure is casy to calculate and has an intuitive interpretation as the average per period welfare of a power utility investor in the portfolio over the time period in question. As an example, consider a fund with returms of -1 , 05,.17, and -.02 . Assume the risk free rate is .01 . In this case T=4,rF is .01 , and if equals 2 Our paper was originally motivated by the question of whether the existing set of performance measures is sufficiently manipulation proof for practical use. This is particularly relevant in the presence of transactions costs, which may offset whatever "performance" gains a manager might hope to generate from trading for the purpose of manipulating the measure. Therefore, our paper explores how difficult it is to meaningfully game the existing measures. For the seven measures examined here - four ratios (Sharpe (1966), Sortino (1991), Leland (1999), and Van der Meer, Plantinga, and Forsey (1999)), and three regression intercepts (the CAPM alpha, Treynor and Mazuy (1966), and Henriksson and Merton (1981)) - the answer is not encouraging. Simple dynamic strategies that only relever the portfolio each measurement period or buy (very liquid) at the money options can produce seemingly spectacular results, even in the presence of very high transactions costs. For example, consider the Henriksson and Merton (1981) measure. A simple options trading scheme in the presence of transactions casts equal to 20% produces "very good" results. The final regression statisties report that the portfolio has returns that are superior to the market's nearly 65% of the time, and (using a 5% critical value) statistically significantly better 9% of the time. Obviously, lower and more realistic transactions costs only make matters worse. The other measures analyzed here are similarly susceptible to having their estimated values gamed. Our results have a number of implications for investment management. Hedge funds and other altemative investment vehicles have broad latitude to invest in a range of instruments, including derivatives. Mitchell and Pulvino (2001) document that merger arbitrage, a common hedge find strategy, generates returns that resemble a short put-shigrt call payoff. Recent research by Agarawal and Naik (2001) shows that hedge fund managers in general follow a number of different styles that are nonlinear in the retums to relevant indices. In a manner - similar to Henriksson and Merton, Agarawal and Naik use option-like payoffs as regressors to capture these non-linearities. In fact, option-like payoffs are inherent in the compensationstructure of the typical hedge fund contrict. Goetmann, Ingersoll and Ross (2001) show that the high water mark contract, the most common type in the hedge fund industry, effectively leaves the investor short 20% of a call option. The call is at-the-moncy cach time it is "reset" by a payment and out-of-the money otherwise. The paper is structured as follows. Section 1 discusses various ways in which the Sharpe ratio can be manipulated. Section 2 discusses the manipulation of a number of other measures including those using reward to variability (Section 2A ) and the Henriksson-Merton and Treynor-Meny market timing measures (Section 2B). Section 3 derives the manipulation proof performance measure, and Section 4 concludes: 1. Manipulation of the Sharpe Ratio Although the Sharpe ratio is known to be subject to manipulation, if remains one of if not the moot widely used and cited performance measures. If, therefore, makes a good example to introduce performance manipulation in mere detail. Other neasures are examined in the next section. 1A. Static Analysis A number of papers have shown that by altering the distribution function governing returns the statistical mean and variance can be manipulated to increase the Sharpe ratio to some degree. Ferson and Siegel (2001) look at a fairly general case (that includes potentially private information) while Lhabitant (2000) shows how using just a couple of options can generate seemingly impressive values. Since the focus of this paper is on dynamic strategies and the development of a MPPM to prevent all sources of manipulation the only static result presented here is the characterization of the retum distribution that maximizes the Sharpe ratio. Readers interested in additional details should consult one of the above cited articles. The Appendix shows that Sharpe ratio maximizing portfolio in a complete market is characterized by a state i return in excess of the interest rate (xi1/3) of xiNSi=xLes[1+SMsh21p^i/pi] Here Ssin=[p^i2/pi1]1/2 is the maximum possible Sharpe ratio, and pi and p^i are the true and risk-neutral probabilities of state i. Since the Sharpe ratio is invariant to leverage, we are free to specify the portfolio's mean excess return, xmas, at any level desired. While the MSR has a number of interesting properties it is also true that one way to mitigate its impact on a fund's apparent performance is to sample returns more frequently. As one does 50 the percentage difference between the market portfoliq''s Sharpe ratio and that of the MSR goes to zero. However, as will be seen below frequent samyting does not help when managers use dynamic manipulation strategies and thus the paper now turns to this issue. 1B. Dynamic Analysis Calculated values of the Sharpe ratio and virtually all other performance measures use statisties based on the assumption that the reported retums are independent and identically distributed. While this may be a good deseription of typical portfolio returns in an efficient market, it clearly can be violated if a portfolio's holdings are varied dynamically depending on its performance. Consider a money manager who has been lucky or unlucky with an average realized return high or low relative to the portfolio's realized variance. The retum distribution in the future will likely not be similar to the experience. Consequently, to maximize the Sharpe ratio, the portfolio can be modified to take into account the difference in the distributions between the realized and future returns just as if the returns distribution was not ex ante identically distributed each period. This dynamie manipulation makes the past and future returns dependent when computed by an unconditional measure. To illustrate, suppose the manager has thus far achieved an historical average excess return of ik, with a standard deviation of ok. The portfolio's average excess returm and atandard deviation is the future are denoted by x, and f. Then is meavured Sharpe ratio over the cobire period will be will be S=(xk2+h2)+(1)(xf2+f2)[xk+(1)xf]2xi+(1)xf=xi2(1+1/Sh2)+(1)xf2(1+1/Sf2)[xh+(1)xf]2xk+(1)xf where y is the fraction of the total time period that has already passed, and a and f are the past and future Sharpe ratios. By inspection, the overall Sharpe ratio is maximized by holding in the future a portfolio that maximizes the future Sharpe ratio, Sf=SMosn.. However, regardless of what Sharpe ratio can be achieved in the future, leverage is no longer irrelevant as it was in the static case. Maximizing the Sharpe ratio in (3), we see that the optimal leverage gives a target mean excess return of xf={xk(1+Sk2)/(1+Sf2)forxk>0forxh0 If the manager has been lucky in the past and achieved a higher than anticipated Sharpe ratio, Sh>Sf, then the portfolio should be targeted in the future at a lower mean excess return (and lower variance) than it has realized. This allows the past good fortune to weigh more beavily in the overall measure. 1 Conversely, if the manager has by en unlucky and Sk0forSh0. Figure 1 plots the overall Sharpe ratio as a function of the realized historical Sharpe ratio for histories of different durations. The overall Sharpe ratio can, on average, be maintained above 'For a fixed Sharpe naio, the overal mean is linear in the futuro leverse white the overall standand deviation is convex. The proportional thanges in the mean and candert devietice with reppect to future loversece are equal when the farture and historical Sharpe ration are equal. Therefore, when the hisarical Shape natio is lew than the future Stape rato, ircteating leverage incteaes the overall mean at a fater rate than the standand deviatice and viee vera. 2 Becaine the optimal furure levenge is infinile when x30. the past Sharpe ratio does not affect the overall sharpe ratio, and the value of the oyerals Sharpe natio for SA0 Clearly, alpha is subject to severe manipulation. A MSRP can be created with any desired leverage, so its alpha can in theory be made as large as desired by levering. The Treynor (1965) ratio and the Treynor appraisal ratio were introduced in part to avoid the leverage problem inherent in alpha. The Treynor measure is the ratio of alpha to beta 6 while the appraisal measure is the ratio of alpha to residual standard deviation. Like the Sharpe measure, and unlike alpha, the two Treynor measures are unaffected by leverage. Both Treynor measures indicate superior performance for the MSRP. The MSRP's two Treynor ratios are? TMSA=MSAMSA=(SMSA2/Smi121)xmi1>0AMSA=Var[xMaiMSAxmai]MSA=SMSA2Smi2>0. Any MSRP has the largest possible Treynor appraisal ratio, but Treynor ratios in excess of the MSRP's can be achieved by forming portfolios with positive alphas and betas close to zero.' In addition, since the Sharpe ratio is subject to dynamic manipulation, alpha and both "If arset i is combined with the market intn a portfolio wx,(1w)x2, then (S/w)1,/ma. "The brea of the maximal-Sharpe-ratio ponfolio, Inse, is whese 5 . in the Sharpe ratio of the market. The thind equality follows since the MSRP is meab-variance efficient "Treytoo's (695s) ceiginal definition of his meanure was r,/; however, / is now the commonly acopeed derifition. Thepter Apraisel rale, we ate 4 and positive alpha. Therefire, its Thereer natio will be ta: Treynor measures are as well and can be increased above these statically achieved values. The manipulation is illustrated in Figure 2. If returns have been above (below) average, then decreasing (increasing) the leverage in the future, will generate a market line for the portfolio with a positive alpha. Not surprisingly, this is very similar to the dynamic manipulation that produces a superior Sharpe ratio - leverage is decreased (increased) after good (bad) returns. [Insert Figure 2 here] Alpha-like measures can also be computed from models other than the CAPM. Under quite general conditions, the generalized alpha of an asset or portfolio in a single-period model is pm=n=xpBpxmwhereBp=Cov[u(1+rf+xm),xm]Cov[u(1+rf+xm),xx] Br is a generalized measure of systematic risk, rr is the per-period (not-annualized) interest rate, and u() is the utility function of the representative investor holding the market. The systematic risk coefficient, B, can be estimated by regressing x on xm using u() as an instrumental variable. Ingersoll (1987) and Leland (1999) suggest using a power utility funetion where u(1+rf+xm)=(1+rf+xm)with=Var[n(1+rf+xm)]n[E(1+rf+xm)]ln(1+rf). This generalized alpha gives a correct measure of mispricing assuming that the representative utility function is correctly matched to the market portfolio; that is, if the market portfolio does maximize the utility function employed. But this statement, tautological as it is, only applies to single-period or static manipulation. Even if the utility is correctly matched to the market, strategically rebalancing the portfolio over time can give an apparent positive alpha due to the deviation between the average and a properly conditioned expectation. The basic technique is the same - decrease (increase) leverage after good (bad) returns. Beyond the single-factor CAPM, there are several alpha-like performance measures in use. These models augment the single factor CAPM model with additional risk factors such as the Fama-French factors. However, within the simulations discussed in the next sub-section, no such factors exist. The market returns are generated in an environment where (8) with amen=0 is the correct way to price. This single factor model should do at least as well in the simulated environment as any model with additional, but within the simulation, unpriced, factors. Similarly, if a multi-factor model were simulated, a multi-dimensional rebalancing of the portfolio should produce positive alphas. For this reason, the Chen and Knez (1996) measure and similar measures have not been examined. 1D. Manipulating the Sharpe Ratio and Alpha with Transactions Costs In practice, a manager can change a portfolio's characteristies far more frequently than once during the typical measurement period. On the other hand, the costs of transacting may "Set Inpendit (1987) for the dervition of this aeneal manue of cyutematic riak eliminate the apparent advantage of many manipulation strategies. As we show below even very high transaction costs cannot prevent managers from manipulating the Sharpe ratio or other performance measures. Determining the optimal dynamic manipulation strategies for all of the popular performance measures is beyond the scope of our paper. The optimal manipulation strategy depends on the size of the transaction costs, the complete set of returns to date within the evaluation period, the distribution of future returns, and the number of periods remaining in the evaluation period. However, for our purposes, an optimal strategy is not necessary. We only want to establish whether reasonably simple trading strategies can distort the existing measures even in the presence of transactions costs, and if so, by bow much. [Insert Table I here] Table I shows the Sharpe ratio performance of a dynamically rebalanced portfolio. The portfolio is always invested 100% in the market with leverage; no derivatives are used to alter the distribution. The leverage starts at one. After the first year, the portfolio is levered at the beginning of each month so that the target mean is given by equation (4) though the leverage is also constrained to be between 0.5 and 1.5 so the portfolio will not be too extreme in nature. The levenge is achieved by buying or selling a synthetic forward contract consisting of a long position in calls and a short position in puts that are at-the-money in present value i.e., the strike price per dollar invested in the market is eett. Trades in these two options are assessed a roundtrip transaction cost of 0%,10%, or 20%. The simulation consisted of 10,000 repetitions. On average the dynamically-manipulated portfolio's Sharpe ratio is 13% higher than the market's and 7% higher than the MSRP's. In the 10,000 trials, the manipulated portfolio had a Sharpe ratio higher than the market's 82.6% of the time in the absence of transactions costs. 10 Even with a 20% round-trip transactions cost, the dynamically-manipulated portfolio still beat the market almost three-quarters of the time. It should be mentioned here that comparing these winning percentages to 50% is a conservative test of how good the manipulated Sharpe ratio is. The CAPM predicts that any portfolio's Sharpe cannot be bigger than the market's - not that it will be bigger or smaller with some measurement error. The Sharpe-manipulated portfolio beats the market frequently, but is it substantially better statistieally; that is, is the difference in the Sharpe ratios significant? In practice this question is seldom asked becuuse Sharpe ratios are at least as difficult to estimate precisely as are mean retums." However, differences between two Sharpe ratios can be more precisely estimated "The frequency with which one portiolio beuts another mast be interpeeted with cmution when the "winning" portiobio bolde derivativea. To illuatrate, consider two porffotion that are almout identical. The only difference in the sesond porifolio sells derivitive awets that bave a poitive payoff only rarely, like docp out-of the money optiona. The procecds are ievested in bonde. Wheneve, the payoff event for the derivative does not occur, then the accend tor the secend porfolole by sinsset any perfonance measure, Since the payoff eveat can be made a rate as decirod obly the levsrege is disnged so bey are not aubject to this probles if the underlying returns are correlated as would generally be true and is certainly true in our example. Statistical tests of portfolio retums generally assume that the returns are independent and identically distributed over time. Such is not the case here for the manipulated portfolio which makes deriving the distribution of the difference in the Sharpe ratios a difficult task. Furthermore, there is little point in doing so as our simulation is a constructed example, and the statistic we derive would be applicable only to that case. Fortunately we need not do so. Our simulations give us a sample distribution of the differences, so we can easily determine how often the difference is k standard deviations above or below zero. For example, with no transactions costs, the difference between the manipulated Sharpe ratio and the