Question: How many hours are the workers working per year? How many hours are needed for 3000 CPs per year? 96090009 MGMT 6147, RSCH 6010, RSC

How many hours are the workers working per year? How many hours are needed for 3000 CPs per year?

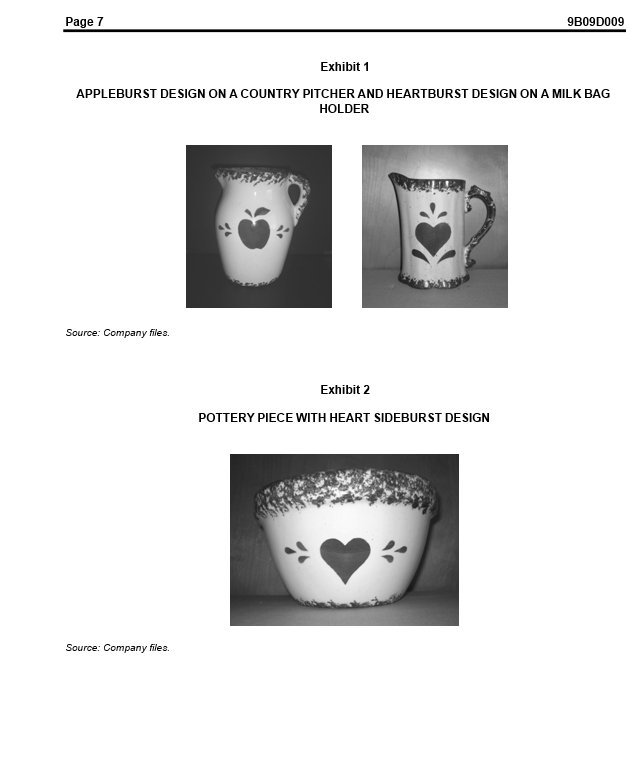

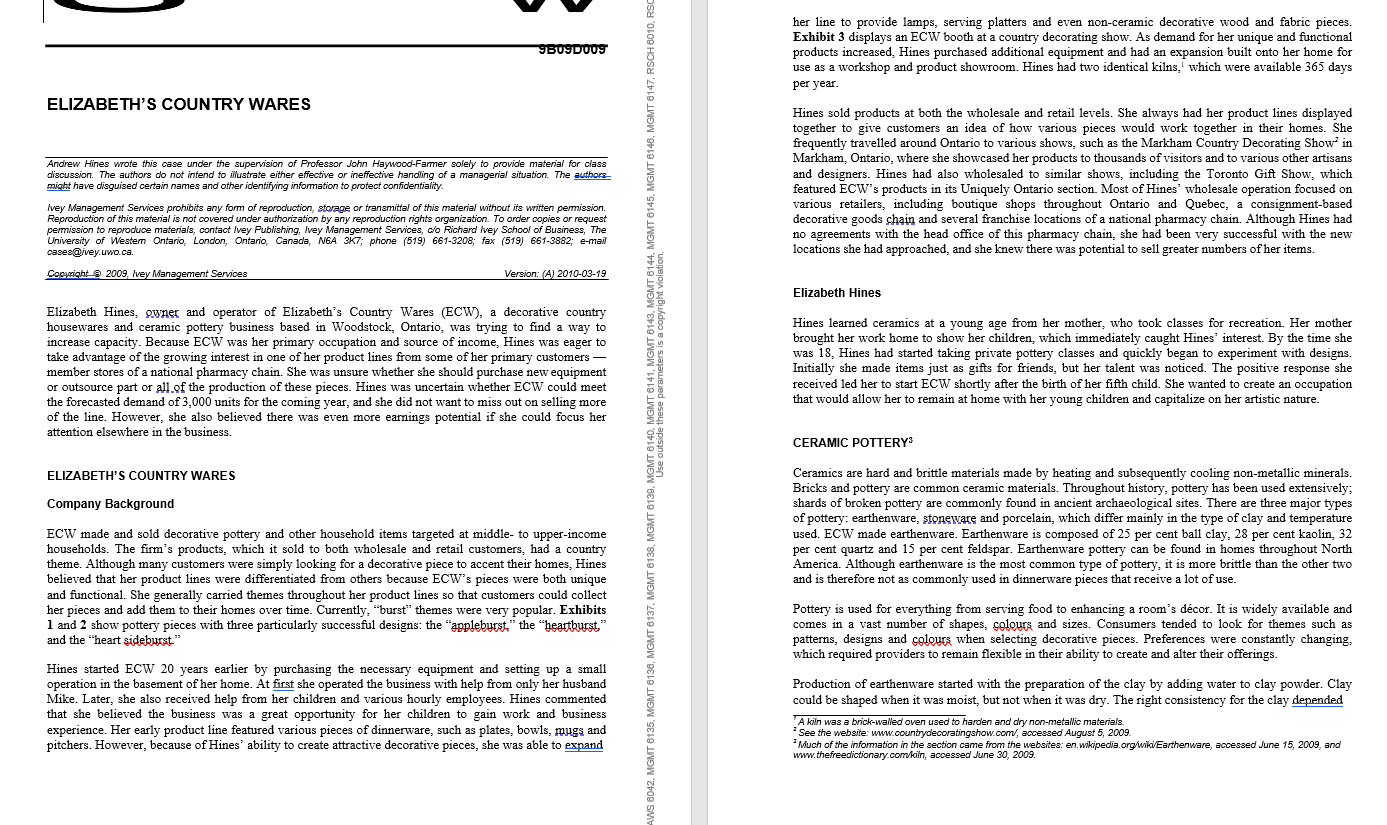

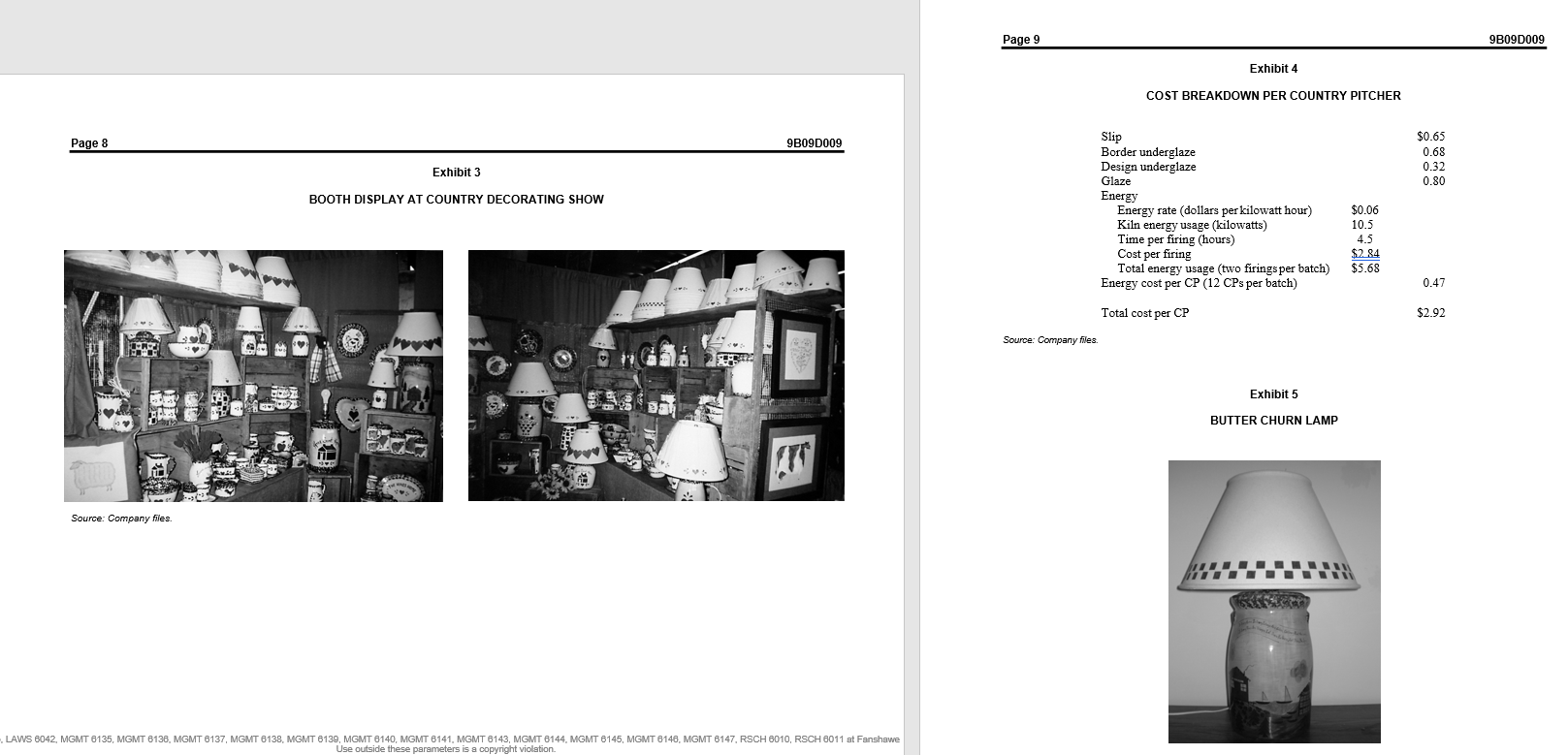

96090009 MGMT 6147, RSCH 6010, RSC her line to provide lamps, serving platters and even non-ceramic decorative wood and fabric pieces. Exhibit 3 displays an ECW booth at a country decorating show. As demand for her unique functional products increased. Hines purchased additional equipment and had an expansion built onto her home for use as a workshop and product showroom. Hines had two identical kilns, which were available 365 days per year. ELIZABETH'S COUNTRY WARES Andrew Hines wrote this case under the supervision of Professor John Haywood-Farmer solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors might have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality Ivey Management Services prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmital of this material without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, do Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 367; phone (519) 661-3208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca. Cogumight 2009, Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2010-03-19 Hines sold products at both the wholesale and retail levels. She always had her product lines displayed together give customers an idea of how various pieces would work together in their homes. She frequently travelled around Ontario to various shows, such as the Markham Country Decorating Show in Markham, Ontario, where she showcased her products to thousands of visitors and to various other artisans and designers. Hines had also wholesaled to similar shows, including the Toronto Gift Show, which featured ECW's products in its Uniquely Ontario section. Most of Hines' wholesale operation focused on various retailers, including boutique shops throughout Ontario and Quebec, a consignment-based decorative goods chain and several franchise locations of a national pharmacy chain. Although Hines had no agreements with the head office of this pharmacy chain, she had been very successful with the new locations she had approached, and she knew there was potential to sell greater numbers of her items. Elizabeth Hines Elizabeth Hines, owner and operator of Elizabeth's Country Wares (ECW), a decorative country housewares and ceramic pottery business based in Woodstock, Ontario, was trying to find a way to increase capacity. Because ECW was her primary occupation and source of income, Hines was eager to take advantage of the growing interest in one of her product lines from some of her primary customers member stores of a national pharmacy chain. She was unsure whether she should purchase new equipment or outsource part or all of the production of these pieces. Hines was uncertain whether ECW could meet the forecasted demand of 3.000 units for the coming year, and she did not want to miss out on selling more of the line. However, she also believed there was even more earnings potential if she could focus her attention elsewhere in the business. Hines learned ceramics at a young age from her mother, who took classes for recreation. Her mother brought her work home to show her children, which immediately caught Hines' interest. By the time she was 18, Hines had started taking private pottery classes and quickly began to experiment with designs. Initially she made items just as gifts friends, but her talent was noticed. The positive response she received led her to start ECW shortly after the birth of her fifth child. She wanted to create an occupation that would allow her to remain at home with her young children and capitalize on her artistic nature. CERAMIC POTTERY ELIZABETH'S COUNTRY WARES Company Background ECW made and sold decorative pottery and other household items targeted at middle-to upper-income households. The firm's products, which it sold both wholesale and retail customers, had a country theme. Although many customers were simply looking for a decorative piece accent their homes, Hines believed that her product lines were differentiated from others because ECW's pieces were both unique and functional. She generally carried themes throughout her product lines so that customers could collect her pieces and add them to their homes over time. Currently, "burst" themes were very popular. Exhibits 1 and 2 show pottery pieces with three particularly successful designs: the "appleburst," the heartburst," and the "heart sideburst." Ceramics are hard and brittle materials made by heating and subsequently cooling non-metallic minerals. Bricks and pottery are common ceramic materials. Throughout history, pottery has been used extensively; shards of broken pottery are commonly found in ancient archaeological sites. There are three major types of pottery: earthenware, stoneware and porcelain, which differ mainly in the type of clay and temperature used. ECW made earthenware. Earthenware is composed of 25 per cent ball clay, 28 per cent kaolin, 32 per cent quartz and per cent feldspar. Earthenware pottery can be found in homes throughout North America. Although earthenware is the most common type of pottery, it is more brittle than the other two and is therefore not as commonly used in dinnerware pieces that receive a lot of use. Pottery is used for everything from serving food to enhancing a room's dcor. It is widely available and comes in a vast number of shapes, colours and sizes. Consumers tended to look for themes such as patterns, designs and colours when selecting decorative pieces. Preferences were constantly changing, which required providers to remain flexible in their ability to create and alter their offerings. Production of earthenware started with the preparation of the clay by adding water to clay powder. Clay could be shaped when it was moist, but not when it was dry. The right consistency for the clay depended A kiln was a brick-walled oven used to harden and dry non-metallic materials. See the website: www.countrydecoratingshow.com, accessed August 5, 2009. Much of the information in the section came from the websites: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earthenware, accessed June 15, 2009, and www.thefreedictionary.comkin, accessed June 30, 2009. Hines started ECW 20 years earlier by purchasing the necessary equipment and setting up a small operation in the basement of her home. At first she operated the business with help from only her husband Mike. Later, she also received help from her children and various hourly employees. Hines commented that she believed the business was a great opportunity for her children to gain work and business experience. Her early product line featured various pieces of dinnerware, such as plates, bowls, mugs and pitchers. However, because of Hines' ability create attractive decorative pieces, she was able to expand Page 3 9B09D009 Page 4 9B09D009 consistency attention to detail, Hines was the only person to perform this step. She commented that it took her 10 minutes paint both sides of the CP and about 2.5 minutes to sponge on the borders and load the piece into one of the two identical kilns. Both kilns were also used on other product lines, one for 90 days per year and the other for 140 days per year. on how it was to be worked. Some potters worked with a pottery wheel - a device that rotated wet clay and allowed potters to shape pieces with their hands or mechanical shaping devices using clay that resembled thick toothpaste in consistency. Pottery thrown on a wheel was invariably circular. Once shaped, the pottery was allowed to dry Potters could also use a pottery mould to shape a slurry of clay in water (also known as slip), which was about the same consistency as waffle batter or thick paint. The potter simply poured slip into an opening in a mould of the desired shape and let the clay harden as the water evaporated. Regardless of how it was shaped, once the clay had dried for a few hours, it was removed from the mould, At this stage, termed 'greenware,' the clay was still moist but firm enough to support its own weight and be worked on. After the greenware piece was sanded remove imperfections and wiped down to remove any dust, the desired designs were applied, using paint known as underglaze. The piece was then kiln fired' at temperatures from 1,000C to 1,150C. Firing both strengthened the piece and set the desired design. At this point in the process, the pottery was called 'bisque.' Depending on preference, some pieces were complete at this stage. However, many pieces of pottery also went through a second firing between 950C and 1,050C after being painted with a glaze which, as the name suggests, formed a glass finish on the piece MGMT 6146, MGMT 6147, RSCH 6010, Loading a kiln required skill and attention to detail. In particular. it was essential that the pieces touch neither each other nor the side of the kiln for the duration of the firing. If pieces did touch the designs on them would be smeared or the pieces would be fused together; in either case, the pieces were usually ruined. Thus, there was a tradeoff between packing the kiln tightly to use the capacity efficiently versus packing it loosely to reduce the risk of ruining some of the pieces. To elevate pieces in the kiln, potters used small ceramic rods called stilts to support the piece. COUNTRY PITCHER Once a kiln was full, it was fired overnight to further harden the clay. The heat and fumes emitted by the kiln while it was running prevented any other activities in the shop for the duration of the kiln cycle. Thus, each kiln could be fired only once per day, regardless of the length or temperature of the cycle. Once the kiln had cooled for several hours, the CPs were unloaded and glazed by a second hourly worker. This worker applied two coats to the entire outside of the piece. Because of the narrow neck on many pottery pieces, the inside could not be painted in the normal way. The glaze worker thus poured some liquid glaze into the piece and then rolled the piece to distribute the glaze on the entire inside surface. Because of the consistency required in the glaze layers, it took the worker about 1.75 hours to unload, glaze and reload an entire run of 12 CPs into the kiln. If no kiln space was available, this worker stockpiled glazed pieces for the next available firing. After the second firing, the glaze worker sanded off the stilt marks that were left on the bottom of the CPs during firing and placed them into the appropriate packaging materials to avoid breakage. This typically took about 24 minutes per run. Both hourly workers were flexible in their availability and could easily perform tasks in other areas of the business when their services in CP production were not needed. Exhibit 4 shows a breakdown of material and energy costs per country pitcher Of particular interest to Hines was her country pitcher (CP) line, one of ECW's primary sellers. It typically featured a hand-painted design that Hines created. She constructed stencils for each design to ensure that customers could easily collect multiple pieces with matching designs. The main designs on ECW's CPs were typically burgundy, accented with either green or blue paint on the rest of the design and border. Each piece had two designs, one on each side. Hines purchased clay slip and took complete responsibility for turning into the final product. Although ceramic pieces of equal or better functionality and lower price were available at various stores, including big-box retailers such as Wal-Mart, these pieces typically did not feature designs. Hines believed that these pieces were too generic and did not appeal to customers in the same way that her uniquely themed pieces did. The country pitcher sold for $25 wholesale. Because of Hines' commitments to her family, producing other product lines and selling at shows during weekends, she was able to dedicate only eight hours per week to country pitcher production. OPTIONS FOR THE FUTURE MGMT 6136, MGMT 6137, MGMT 6138, MGMT 6139, MGMT 8140. MGMT 614, MicMoricht violation.* Operations Hines recognized the potential to make more money from her country pitchers featuring generic designs. She believed that the process of stencilling the basic designs onto the CPs was an inefficient use of her time. When not working on CP production, she could spend her time working on larger, higher margin items, such as butter churn lamps, which generally featured completely unique designs where no stencilling was involved (see Exhibit 5). Hines believed that if she could dedicate the time she spent on the stencilled CPs to the marketing and production of butter churn lamps, she could sell two to three additional units per week.' Butter churn lamps sold for $350 retail and had a margin of 60 per cent. ECW's CP production employed two part-time hourly workers, who were paid $15 per hour, including benefits. When working on CPs, one worker worked solely on greenware. The other was responsible for glazing and glazing the CPs. In the first step, the greenware worker poured slip into a plaster mould and then set it aside to allow the clay to harden a little. The greenware worker then opened the mould and cut off any excess clay around the edges of the CP, being careful not to disfigure or damage the still-soft clay. The excess clay was recycled. The CP was then set on a shelf to dry. Dried CPs were sanded and wiped down by the greenware worker to remove any visible imperfections. The process of pouring, opening and cleaning was staggered to ensure that the worker was always occupied, in spite of the required drying and hardening stages. Hines commented that performing all those tasks on one CP generally took about 20 minutes of the greenware worker's time. Next, Hines painted on the desired design (heartburst, heart sideburst or appleburst) and sponge painted on the border using underglaze. Because of the need for Purchase Decal Equipment Hines believed there was an opportunity to save time by using decals produced by a digital system. The designs for the decals could be stored and edited on a computer, and then printed whenever needed. Decals could be transferred onto the CPs without the use of skilled labour, Although such a move would diminish Hines' ability to claim that her pieces were "hand painted," she had never actually promoted that issue. She was also concerned that the Chinese supplier might use lead-based glazes. Years earlier Hines had switched to lead-free glazes because of the increasing public awareness of the possibility of lead poisoning through the use of pottery. The Shenzhen supplier assured Hines that it would use lead- free glaze. However, the lack of strong manufacturing regulations coupled with weak enforcement in China, Hines wondered how she could be sure that lead would not end up in her products, regardless of the supplier's promises. THE DECISION aspect of her work. In her opinion, the CPs would maintain their unique and "country" appeal. She hoped customers would be impressed by the improved consistency of the designs. To create the decals, Hines would need to purchase a computer system valued at $700, a specialized decal scanner/printer combo and laminator that would cost roughly $3,000, and a third kiln that would cost $2,700 plus $200 for installation. The kiln would be used to burn decal designs into the finish of the CP. Hines hoped to avoid buying two additional kilns because she knew that decal application required much cooler and shorter cycles. She was confident that if she kept the windows open and the exhaust vent on during firing, it would be possible to run the third kiln many times per day. With the use of the system, Hines believed she could completely remove herself from the production of CPs after only minimal training of a replacement worker. The underglazing step would then consist of only border painting and loading, and it could be completed by an hourly worker currently employed elsewhere in the business. The same worker would also be responsible for applying a decal to both sides of the CP. Hines believed that in less than two minutes, any unskilled worker could remove the CPs from the kiln, apply the decals and place the CPs into the new kiln for their third and final firing. Additional electricity used by the new kiln would amount to $2.40 per run. ECW would also incur a cost of $1.88 per decal used. Hines liked the idea of having complete control over production and designs but wondered whether the investment was necessary. Although she knew that digitally produced designs were becoming a standard in the industry, she had never worked with this type of equipment herself. With increasing interest in her CPs, Hines did not want to dedicate even more of her time to what she considered to be a monotonous task. She sat back at her kitchen table and wondered what she should do. A demand for 3.000 CPs in the coming year was hard to ignore. Whatever she chose, she would have to make a decision soon as many new pharmacy locations had already enquired about placing orders. Outsource Decal Production Hines had recently spoken with a decal supplier located in New York State, less than five hours away by car. The company supplied customers with customized decals using the traditional method of screen printing and was very enthusiastic about producing both of Hines' heart-based designs. Hines had worked with this type of decal before with positive results. She knew that this method had a reputation for yielding unmatchable colour possibilities. Although the application process for this decal would be identical to the application of the digitally produced decals, the decals would cost significantly more at $5.76. Hines specifically liked the fact that this option had minimal investment. A single, upfront cost of $500 per design was required by the company for setting up the screens and proofing to ensure the design was to specifications. MGMT 6135, MGMT 6138, MGMT 6137. MGMT 6138, MGMT 6130, MGM GMT. 14. MISA TORNAR AN GAMPE 61.94, MGMT 6145, MGMT 6146, MGMT 6147, RSCH 6010, RS Outsource CP Production Hines noticed that major competition for pottery came from Asian providers. Because these products were imported from countries that benefited from cheaper labour costs, Hines believed she had little ability to compete price. However, she wondered whether she might be able to take advantage of an opportunity. She had also recently been in contact with a ceramics manufacturing company in Shenzhen, China, that was willing to take on her CP production. Although the option would require no upfront payment, Hines would have to commit to having her entire 3,000-unit demand produced by the vendor at a flat rate of $8.45 per CP after delivery. The option would not only free up Hines' time to work on other lines, but it would also free up her production facility and the time of her employees to be used in other areas. Hines knew that many ceramics manufacturers had done quite well with plain coloured CPs, but she had never seen anything that featured designs like hers. The company informed her that it would be using decal technology similar to the digital equipment she was considering purchasing. Hines was interested in the idea of freeing up her production facility, but she had no experience with outsourcing. She wondered whether the 40-day lead time the supplier required for orders might be an Page 7 9B09D009 Exhibit 1 APPLEBURST DESIGN ON A COUNTRY PITCHER AND HEARTBURST DESIGN ON A MILK BAG HOLDER Source: Company files Exhibit 2 POTTERY PIECE WITH HEART SIDEBURST DESIGN Source: Company files Page 9 9B09D009 Exhibit 4 COST BREAKDOWN PER COUNTRY PITCHER Page 8 9B09D009 $0.65 0.68 0.32 0.80 Exhibit 3 BOOTH DISPLAY AT COUNTRY DECORATING SHOW Slip Border underglaze Design underglaze Glaze Energy Energy rate (dollars per kilowatt hour) Kiln energy usage (kilowatts) Time per firing (hours) Cost per firing Total energy usage (two firings per batch) Energy cost per CP (12 CPs per batch) $0.06 10.5 4.5 $2.84 $5.68 0.47 Total cost per CP $2.92 Source: Company files Exhibit 5 BUTTER CHURN LAMP Source: Company files. .LAWS 6042, MGMT 6135, MGMT 6136. MGMT 6137, MGMT 6138, MGMT 8139, MGMT 6140, MGMT 6141. MGMT 6143, MGMT 6144, MGMT 6145, MGMT 6146, MGMT 6147, RSCH 6010, RSCH 6011 at Fanshawe Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation