Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

my question about :- 1) Introduction about this case study 2)Key dimentions of quality in aravind eye hospital 3)your managerial perspective and opinion related to

my question about :-

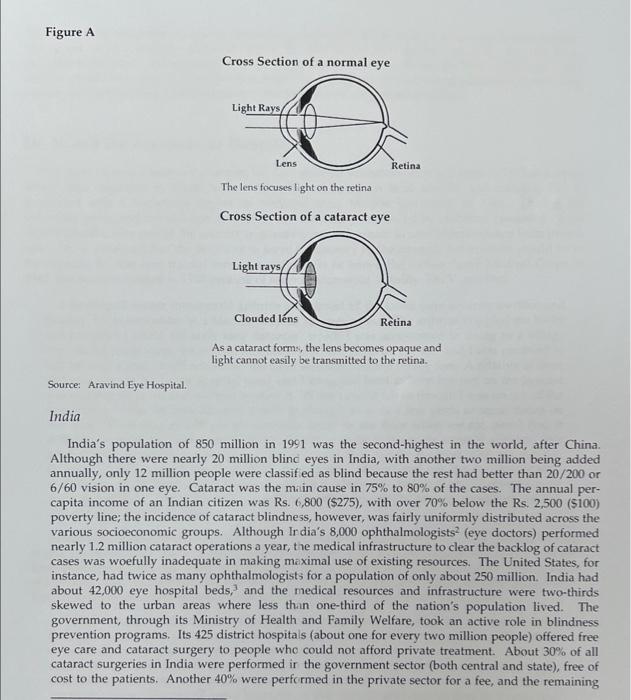

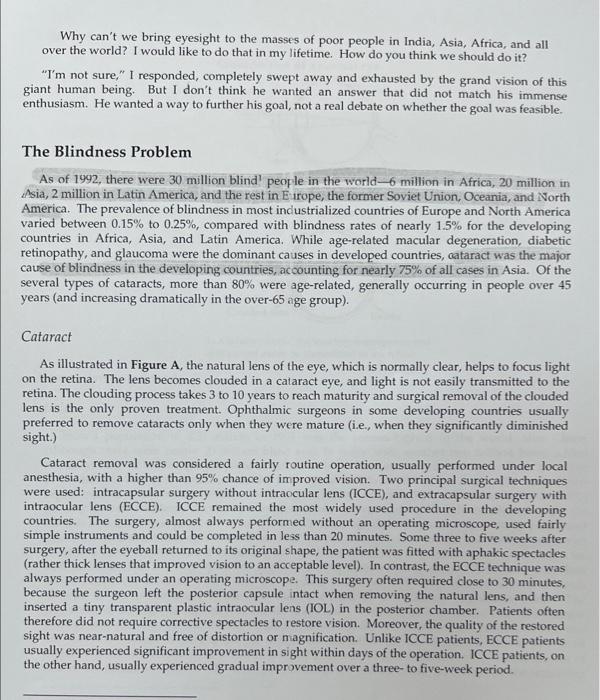

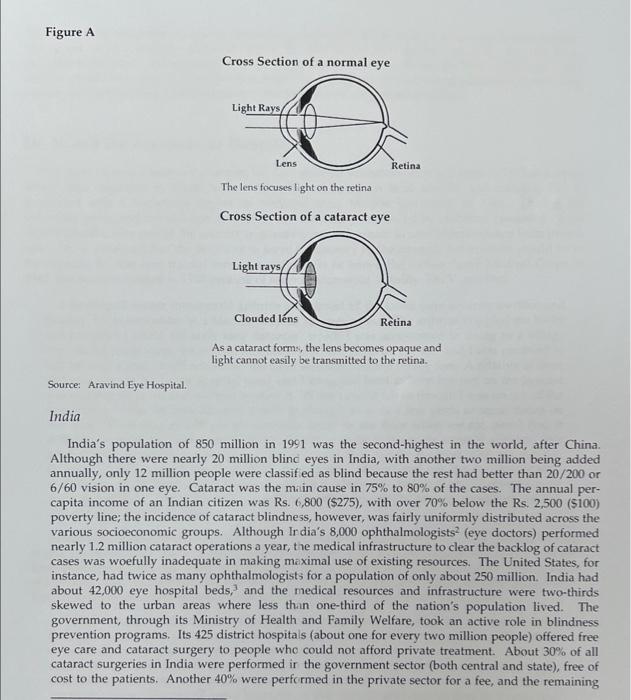

for Sight I (the casewriter) arrived early at 7:00 a.m at the outpatient department of the Aravind Eye Hospital at Madurai, India. My sponsor, Thulasi (R.D. Thulasiraj, hospital administrator), was expecting me at 8:00 o'clock, but I came early to observe the patient flow. More than 100 people formed two lines. Two young women, assisted by a third, were briskly registering the patients at the reception counter. They asked a few key questions: "Which village do you come from?" "Where do you live?" "What's your age?" and a few more, but it all took less than two minutes per patient. The women seemed very comfortable with the computer and its data-entry procedures. Their supervisor, a somewhat elderly man with grey hair, was hunched over, gently nudging and helping them along with the registration process. He looked up and spotted me. I was the only man in that crowd who wore western-style trousers and shoes. The rest wore the traditional South Indian garment ("dhoti" or "veshti"), and many were barefooted because they could not afford "slippers." The old man hobbled from the registration desk and made his way toward me. The 50 -foot distance must have taken him 10 minutes to make because he paused every now and then to answer a question here or help a patient there. I took a step forward, introduced myself, and asked to be guided to Thulasi's office. "Yes, we were expecting you," he said with an impish smile and walked me to the right wing of the hospital where all the administrative offices were. He ushered me into his office and pointed me to the couch across from his desk. It was only when I noticed his crippled fingers that I realized this grand old man was Dr. Venkataswamy himself, the 74 -year-old ophthalmic surgeon who had founded the Aravind Eye Hospital and built it from 20 beds in 1976 to one of the biggest hospitals of its kind in the world in 1992, with 1,224 beds. Dr. V. spoke slowly and with a childlike sense of curiosity and excitement: Tell me, can cataract surgery be marketed like hamburgers? Don't you call it social marketing or something? See, in America, McDonald's and Dunkin' Donuts and Pizza Hut have all mastered the art of mass marketing. We have to do something like that to clear the backlog of 20 million blind eyes in India. We perform only one million cataract surgeries a year. At this rate we cannot catch up. Modern communication through satellites is reaching every nook and corner of the globe. Even an old man like me from a small village in India knows of Michael Jackson and Magic Johnson. [At this point, Dr. V. knew that he had surprised me. He suppressed a smile and proceeded.] Why can't we bring eyesight to the masses of poor people in India, Asia, Africa, and all over the world? I would like to do that in my lifetime. How do you think we should do it? "I'm not sure," I responded, completely swept away and exhausted by the grand vision of this giant human being. But I don't think he wanted an answer that did not match his immense enthusiasm. He wanted a way to further his goal, not a real debate on whether the goal was feasible. The Blindness Problem As of 1992 , there were 30 million blind 3 peof le in the world -6 million in Africa, 20 million in Asia, 2 million in Latin America, and the rest in Europe, the former Soviet Union, Oceania, and North America. The prevalence of blindness in most incustrialized countries of Europe and North America varied between 0.15% to 0.25%, compared with blindness rates of nearly 1.5% for the developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. While age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma were the dominant causes in developed countries, cataract was the major cause of blindness in the developing countries, accounting for nearly 75% of all cases in Asia. Of the several types of cataracts, more than 80% were age-related, generally occurring in people over 45 years (and increasing dramatically in the over-65 age group). Cataract As illustrated in Figure A, the natural lens of the eye, which is normally clear, helps to focus light on the retina. The lens becomes clouded in a calaract eye, and light is not easily transmitted to the retina. The clouding process takes 3 to 10 years to reach maturity and surgical removal of the clouded lens is the only proven treatment. Ophthalmic surgeons in some developing countries usually preferred to remove cataracts only when they were mature (i.e., when they significantly diminished sight.) Cataract removal was considered a fairly routine operation, usually performed under local anesthesia, with a higher than 95% chance of improved vision. Two principal surgical techniques were used: intracapsular surgery without intraocular lens (ICCE), and extracapsular surgery with intraocular lens (ECCE). ICCE remained the most widely used procedure in the developing countries. The surgery, almost always performed without an operating microscope, used fairly simple instruments and could be completed in less than 20 minutes. Some three to five weeks after surgery, after the eyeball returned to its original shape, the patient was fitted with aphakic spectacles (rather thick lenses that improved vision to an acceptable level). In contrast, the ECCE technique was always performed under an operating microscope. This surgery often required close to 30 minutes, because the surgeon left the posterior capsule intact when removing the natural lens, and then inserted a tiny transparent plastic intraocular lens (IOL) in the posterior chamber. Patients often therefore did not require corrective spectacles to restore vision. Moreover, the quality of the restored Cross Section of a normal eye The lens focuses light on the retina Cross Section of a cataract eye As a cataract form:, the lens becomes opaque and light cannot easily be transmitted to the retina. Source: Aravind Eye Hospital. India India's population of 850 million in 1991 was the second-highest in the world, after China. Although there were nearly 20 million blinc eyes in India, with another two million being added annually, only 12 million people were classif ed as blind because the rest had better than 20/200 or 6/60 vision in one eye. Cataract was the mi in cause in 75% to 80% of the cases. The annual percapita income of an Indian citizen was Rs. 6,800($275), with over 70% below the Rs, 2,500 (\$100) poverty line; the incidence of cataract blindness, however, was fairly uniformly distributed across the various socioeconomic groups. Although In dia's 8,000 ophthalmologists 2 (eye doctors) performed nearly 1.2 million cataract operations a year, the medical infrastructure to clear the backlog of cataract cases was woefully inadequate in making maximal use of existing resources. The United States, for instance, had twice as many ophthalmologists for a population of only about 250 million. India had about 42,000 eye hospital beds, 3 and the medical resources and infrastructure were two-thirds skewed to the urban areas where less than one-third of the nation's population lived. The government, through its Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, took an active role in blindness prevention programs. Its 425 district hospitals (about one for every two million people) offered free eye care and cataract surgery to people who could not afford private treatment. About 30% of all cataract surgeries in India were performed ir the government sector (both central and state), free of cost to the patients. Another 40% were performed in the private sector for a fee, and the remaining 30% were performed free of cost by volunteer groups and NGO s (nongovernmental organizations). The government currently allocated about Rs 60 million ( $2 million) annually for blindness prevention programs. A recent report to the Worid Bank estimated that nearly $200 million (Rs. 6,000 million) would be required immediately to build the infrastructure for training personnel, purchasing equipment, and building facilities to overcome the country's blindness problem. Dr. V. and the Aravind Eye Hospital The eldest son of a well-to-do farmer, Dr. Govindappa Venkataswamy was born in 1918 in a small village near Madurai in South India. After his education in local schools and colleges, Dr. V. graduated with a bachelor's degree in medicine from Madras University in 1944. During his university years, and immediately thereafter, he vras deeply influenced by Mahatma (meaning "great man") Gandhi, who united the country in a nonviolent movement to seek independence from British rule. Dr. V. reasoned that the best way to serve his country in the struggle for freedom would be in the capacity he was best trained for-as a doctor. So he joined the Indian Army Medical Corps in 1945 , but was discharged in 1948 because of severe rheumatoid arthritis. Dr. V. recalled, I developed severe rheumatoid arthritis and almost all the joints were severely swollen and painful. I was bedridden in a Madras hospital for over a year. The arthritis crippled me badly and for years I could not walk long distances, which I was accustomed to doing as a village boy. In the acute stage, for several months I could not stand on my feet and I was confined to bed for over a year. I still remember the day I was able to stand on my feet. A relative of mine had come to see me in the hospital ward and I struggled hard to keep my feet on the ground and stand close to the bed without holding it. When I did, it felt as though I was on top of the Himalayas. Then, for several years, I used to struggle to walk a few yards or squat down on the floor. Even now in villages we normally squat on the floor when we eat, and I find it difficult. I could not hold a pen with my fin gers to write in the acute stage of arthritis. We normally eat food with our fingers. 1 found it difficult to handle the food with my swollen fingers, Later I trained slowly to hold the surgeon's scalpel and cut the eye for cataract operations. After some years, I could stand for a whole day and perform 50 operations or more at a stretch. Then I learned to use the (perating microscope and do good, high-quality cataract and other eye surgeries. By the time of his retirement in 1976, Dr. V. hid risen to head the Department of Ophthalmology at the Government Madurai Medical College and also to head Eye Surgery at the Government Erskine Hospital, Madurai. After retirement, in crder to fulfill a long-cherished dream-the creation of a private, nonprofit eye hospital that would provide quality eye care-Dr. V. founded the Aravind Eye Hospital, named after an Indian philosopher ind saint, Sri Aurobindo. Dr. V. noted: What I learnt from Mahatma Gandhi and Swami [saint] Aurobindo was that all of us through dedication in our professional lives can serve humanity and God. Achieving a sense of spirituality or higher consciousness is a slow, gradual process. It is wrong to think that unless you are a mendicant or a martyr you can't be a spiritual person. When I go to the meditation room at the hospital every morning, I ask God that I be a better tool, a receptacle for the divine force. We can all serve humanity in our normal professional lives by being more generous and less selfish in what we do. You don't have to be a "religious" person to serve God. You serve God by serving humanity. History The 20-bed Aravind Eye Hospital opened in 1976 and performed all types of eye surgery; its goal was to offer quality eye care at reasonable cost. The first three surgeons were Dr. V; his sister, Dr. G. Natchiar; and her husband, Dr. P. Namperumalswamy (Dr. Nam). A 30-bed annex was opened in 1977 to accommodate patients convalescing ifter surgery. It was not until 1978 that a 70-bed free hospital was opened to provide the poor with free eye care. It had a four-table operating theater with rooms for scrubbing, changing, and sterilization of instruments. A main hospital (for paying patients), cor menced in 1977 and completed in 1981, had 250 beds with 80,000 square feet of space in five floors four major operating theaters (two tables per theater), and a minor one for septic care. There we se specialty clinics in the areas of retina and vitreous diseases, cornea, glaucoma, and squint corrections, diabetic retinopathy, and pediatric ophthalmology; the heads of all but one of tt ese clinics were family members of Dr. V., and all had received training in the United States. The Main Hospital was well-equipped with modern, often imported, equipment to provide the best pos ible eye care for its patients. In 1992, there were about 240 people on the hospital's staff, including about 30 doctors, 120 nurses, 60 administrative personnel, and 30 housekeeping and mainten nce workers. In 1984 a new 350-bed free hospital was of ened. A "bed" here was equivalent to a 63 mattress spread out on the floor. This five-story hosj ital had nearly 36,000 square feet of space and its top story accommodated the nurses' quarters for he entire Aravind group of hospitals. The hospital had two major operating theaters and a minor the ster for septic cases. On the ground floor were facilities for treating outpatients; in-patients were hrused in large wards on the upper floors. The Free Hospital was largely staffed with medical pirsonnel from the Main Hospital. Doctors and nurses were posted in rotation so that they served both facilities, thereby ensuring that nonpaying and paying patients all received the same quality of eye care. Until 1989, all the patients in the Free Hos pital were attracted from eye camps. In 1990, Aravind opened its Free Hospital to walk-in patient:. Every Saturday and Sunday, teams of doctors and support staff with diagnostic equipment f inned out to several rural sites to screen the local population. Eye camps were sponsored e'ents, where a local businessman or a social service organization mobilized resources to inform the local public within about a 25- to 50-mile radius of the forthcoming screening camp. Camps were u ually held in towns that served as the commercial hub for a number of neighboring villages. Locil schools, colleges, or marriage halls often served as campsites. Patients from surrounding villag s who traveled by bus to the central (downtown) bus stand, were transported to the campsite by t ie sponsors. Several patients from the local area came directly to the campsite. The Aravind team screened patients at the camp, and those selected for surgery were transported the same afternoo i by bus to the Free Hospital at Madurai. They were returned three days later, after surgery and recuperation, back to the campsite where their family members picked them up. Patients who cane from nearby villages were taken to the central bus stand and provided return tickets to their appropriate destinations. A clinical team from Aravind went back to the campsite after three month for a follow-up evaluation of the discharged patients. Patients were informed of the dates for the follow-up camps well in advance-in many cases, at the time of the initial discharge after surgery. Alavind provided the services of its clinical staff and free treatment for the patients selected for surg ry; the camp sponsors bore all other administrative, logistical, and food costs associated with th: camp. (Exhibit 1 shows the location of the various Aravind hospitals; Exhibits 2 and 3 show the inpatient ward at the Aravind Main Hospital. Free Hospital, and some typical eye camp activitie?.) As the Aravind Eye Hospital grew from a 20-bed to a 600-bed hospital, many members of Dr. V.'s family joined in support of his ideals. His brother, G. Srinivasan, a civil engineering contractor. constructed all the hospital buildings at cost an 1 later became the hospital's finance manager. A nephew, R.D. Thulasiraj (Thulasi), gave up a nanagement job in private sector to join as the hospital's administrator. Thulasi, at Dr. V.'s insistence, trained at the University of Michigan in public health management before assuming administrative duties at Aravind. Thirteen ophthalmologists on the hospital's staff were ryated to Dr. V. In order to provide continuous training to its ophthalmic personnel, Aravind ad research and training collaborations with St. Vincent's Hospital in New York City and the University of Illinois' Eye and Ear Infirmary in Chicago: both institutions also regularly sent their own o hthalmologists for residency training to Aravind. Aravind was also actively involved in training ophthalmic personnel in charge of administering blindness prevention projects in other parts of A ia and Africa. Explaining the unfailing support of his family members, Dr. V, recalled: We have always been a joint family throug , thick and thin. I was 32 when my father died. I was the eldest in the family, and in a family :ystem like ours, I was responsible for educating my two younger brothers and two younger sis ters, for organizing and fixing their marriagesthat is the usual custom we have-for finding suitable partners for them. I was the head of the family and looked after all of them. But that was not a problem. I was not married, because of my arthritis trouble. Now it has become a boon. My brother takes care of me, and I stay with him all the time. His children are as much attached to me as they are to him. Dr. Natchiar, Dr. V.'s sister and now the hospi al's senior medical officer, elaborated: When Brother retired from government :ervice, he seemed awfully impatient to serve society in a big way. He asked me and my husband [Dr. Nam] if we would give up our government jobs to join him. Usually in Indix, when one leaves government service to enter private practice, incomes go up threefold. In t is case, we were told that our salaries would be about Rs. 24,000 a year (approximately $1,500 in 1980). And worse still, Brother always believed in pushing the mind and body to its uighest effort levels. So we would have to work twice as hard for half the salary. My husbanil and I talked it over and said yes. We did not have the heart to say no. But what we lost in earnings was made up by the tremendous professional support that Brother gave us. We were encouraged to attend conferences, publish papers, buy books, and do anything to advance our professional standing in the field. It is only in the last five years that our senior surgeons' salaries are reasonably consistent with their reputation in the field. On his insistence that the hospital staff be tot.lly committed and dedicated to the mission of the Aravind Hospital, Dr. V. expressed his philosophy: We have a lot of very capable and intelligent people, all very well trained in theoretical knowledge. But knowledge by itself is not goi ig to save the world. Look at Christ; you cannot call him a scholar, he was a spiritual man. What we need is dedication and devotion to the practice. When doctors join us for residencias, we gradually condition them physically for long hours of concentrated work. Most believe they need work only for a few hours and that, too, for four days a week. In government hospitals, rarely do surgeons work for more than 30 hours a week; we normally expect our doctors to go 60 hours. Moreover, in the government hospitals there is a lot of bureaucracy and cor uption. Patients feel obliged to tip the support staff to get even routine things done. Worse still, poor villagers feel totally intimidated. We want to make all sorts of people feel at ease, and this can only come if the clinical staff and their support staff view the entire exercise as a spiritual experience. Aravind Eye Hospital: 1992 By 1988 , in addition to the 600 beds at Madurai, a 400 -bed hospital at Tirunelveli, a bustling rural town 75 miles south of Madurai, and a 100 bed hospital at Theni, a small town 50 miles west of Madurai, were also started (see Exhibit 1). T7 ere were plans afoot to set up a 400-bed (Rs. 10 million) hospital at Coimbatore, a city 125 miles north of Maduni. Coimbatore, like Madurai, was the hub of its district and was bigger than Madurai in population and commerce. Dr. Ravindran, a family member who currently headed the Tirunelveli Hospital was slated to run the Coimbatore Hospital. Succession plans for the Tirunelveli Hospital would then have to be worked out. Managing the Theni Hospital, which was located in Dr. Nam's home town, was not a big problem: first, because the facility was small, and second, because of the informal supervision it received whenever Dr. Nam visited his home town. In fact, Dr. Nam had been instrumental in setting up this facility to serve his community. In Madurai, by adding a block of 50,000 square feet to the Main Hospital and some reorganization in the Free Hospital, another 124 beds were added in 1991-74 in the Main Hospital and 50 in the Free Hospital, respectively. By 1992, the Aravind group of hospitals tad screened 3.65 million patients and performed some 335,000 cataract operations - nearly 70% of them free of cost for the poorest of India's blind population. (See Exhibit 4 for a performance summary since the hospital's inception in 1976, and Exhibit 5 for details of its 1991 performance) All this was achieved with very little outside aid or donations. According to Dr. V:i When we first started in 1976, we went around asking for donations, but we dian't have the credibility. A few friends promised to help us, but even they preferred to avoid monetary assistance. It was simple: we had to get s arted. So I mortgaged my house and raised enough money to start. Then one thing led to another and suddenly we were able to plan the ground floor of the Main Hospital. From the revenue generated from operations there, we built the next floor, and so on until we had a nice five-story facility. And then with the money generated there, we built the Free Hospital. Almost 90% of our annual budget is selfgenerated. The other 10% comes frori sources around the world, such as the Royal Commonwealth Society for the Blind [U.K.] and the SEVA Foundation [USA]. We expend all our surplus on modernizing and updating our equipment and facilities. We have enough credibility now to raise a lot of money, but we don't plan to. We have always accepted the generosity of the local business community, but by and large, our spiritual approach has sustained us. (See Exhibit 6 for a 1991-1992 statement of income and expenses.) Having grown from strength to strength, Aravind in 1991 made a bold move to set up a facility for manufacturing intraocular lenses (IOLs). IOL factory IOLs, which were an integril part of ECCE surgery, cost about $30(R.800) apiece to import from the United States. At a cost of Rs. 8 million, in 1991. Aravind had therefore set up a modern IOL manufacturing facility. Called the Auro Lab, it could produce up to 60,000 IOL a year. Currently, Auro Lab production yielded about 50% defect-free lenses, quality rated on par with imported lens. Mr. Balakrishnan, a family member with extensive engineering experience and doctoral education in the United States, had returned to manage Auro Lab. Dr. V. reasoned that within a year or two when the factory yield improved, it would be possible to bring down the manufacturing costs from approximately Rs. 200 per lens to approximately Rs. 100 : People come for cataract surgery very late in life, because the quality of regained vision after intra-cap surgery is so-so, but not excellent. With extra-cap surgery and IOL implants, the situation is dramatically different. People would opt for surgery earlier, because they can go back to their professions and be productive right away. My aim is to offer 100% IOL surgeries for all our patients, paying and free. That is the better-quality solution, and we should provide it to all our patients. Thulasi, Aravind's hospital's administrator, explained the challenges ahead (see Exhibit 7 for occupancy statistics): Yes, our expansion projects are all very exciting but we cannot take our eye off the ball. We have to concentrate on the things that made us good in the first place. For instance, my biggest concern is the occupancy rate in the free hospital. On Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday we are choked and overflowing with patients. Our systems have all got to work at peak efficiency to get by. But on Thursday and Friday, we sucidenly have a slack. We need some continuity to keep our staff motivated and systems tuned. Dr. Ravindran, head of the Tirunelveli hospital, concurred: We have some fundamental management problems to sort out. While our cash flows and margins look all right at Tirunelveli, I am unable to repay the cost-of-capital. Thank God, Madurai buys all the equipment on our behalf. We started the Tirunelveli hospital with a lot of hope and experience. Even the physical design was an improvement over our Madurai facility. We have integrated the paying and free hospitals for economies of scale. The wards and patient examination rooms in the free section are far more spacious than at Madurai. Moreover, in order to better utilize operating room capacity, we have a central surgical facility which the free and paying sections of the hospital jointly utilize. Yet, after four years, we are not yet financially self-sufficient at Tirunelveli. Thulasi mentioned another issue: When we expand so fast, we have to keep in mind that we need to attract quality people. Fortunately our salary scales are now reasonatle in comparison with the private sector, but we are still not there. For example, an ophthalmologist at Aravind would today, on an average, make Rs. 80,000 annually. Not bad, compared to government sector salaries of about Rs. 60,000 . Of course, in private practice, some ophthalmologists can make Rs. 300,000 . But not everyone has the up-front capital to get top-rotch equipment to facilitate such practice. Our nurses are paid Rs. 12,000 a year on avernge. which is not bad at all given that our staff is recruited and trained from scratch by us. Thy don't come from nursing school; we provide the training for them. It is like getting a prestiyious degree and job training all in one. A Visit to the Aravind Eye Hospital The Main Hospital Located one block from the Free Hospital, the Main Hospital functioned very much independently. Complicated cases from the Frae Hospital were brought in when necessary for diagnosis and treatment, but by and large all patients at this hospital paid for the hospital's services. Patients came to this hospital from all over Madurai district (i.e., towns and villages surrounding the city). The cost of a normal cataract surgery (ICCE), inclusive of three to four days' post-operative recovery, was about Rs. 500 to Rs. 1,000. If the patient required an IOL implant (ECCE), the total cost of the surgery was Rs. 1,500 to Rs. 2,500. The hospital provided A, B, and C class rooms, each with somewhat different levels of privacy and facil ties and appropriately different price levels. The morning rush was usually very heavy, and by early afternoon, most people divided into two groups for a sequential series of evaluations. First, ophthalmic assistants recorded each person's vision. The patient then moved to the next room for a preliminary eye examination by an eye doctor. There were several eye doctors on duty, and ophthalmic assistants noted the preliminary diagnosis on the patient's medical record. Ophthalmic assistants then tested patients for ocular tension and tear duct function, followed by refraction tests. The final examination was always conducted by a senior medical officer. Not all patients passed through every step; for example, those referred to specialty clinics (such as retina and vitreous cliseases) would directly move to the specialty section of the hospital on the first floor. Similarly, patiunts diagnosed as needing only corrective lenses would move to the optometry room for measurement and prescription of glasses. Those diagnosed as requiring cataract surgery would be advised in-patient admission, usually within three days. Most such patients followed up on the advice. On the day of the surgery, the patient was usually awakened early, and after a light breakfast, was readied for surgery. On a visit to the opers ting theater, I noticed about 20 patients seated in the hallway, all appropriately prepared by the medical staff to enter into surgery, and another 20 in the adjacent room in the process of being readied by the nursing staff. The procedure involved cleaning and sterilizing the eye and injecting a locil anesthetic. The operating theater had two active operating tables and a third bed for the patient to be prepared prior to surgery. I (the casewriter) watched several operations performed by Dr. Natchiar. She and her assistants took no more than 15 minutes for each ECCI: cataract surgery. She generously offered me the east port of the operating microscope to observe the surgical procedure. She operated from the north port, directly behind the patient's head. A resident in training from the University of Illinois occupied the west port. I had never seen a calaract surgery before, but was amazed at the dexterity of her fingers as she made the incision and gently removed the clouded lens, leaving the posterior chamber in place. Then she inserted the IO- [intraocular lens], and carefully sutured the incision. Even while she was operating, she explainec to me in a methodical step-by-step fashion the seven critical things she had to do to ensure a successful operation and recovery. When she was done, she simply moved on to the adjacent operating able, where the next patient and a second supporting team were all ready to go. Meanwhile, the previous surgical team helped the patient off the operating table to walk to the recovery room ind prepared the next patient, who was already waiting in the third bed for the next surgery. Dr. Natchiar had started that day at about 7:30a.m, and when I left at about 10:30a.m, was still going strong in a smooth, steady, uninterrupted fashion. The whole team carried on about their tasks in a well-piced, routine way. There was none of the drama I had expected to encounter in an operating theater In contrast, Dr. Nam was performing a retina detachment repair in the adjoining operating theater. Without looking up from his task, Dr. Nam told me that he was in the midst of a particularly difficult procedure and it would probably be another hour before he could comfortably converse. His surgical team bent over the operating able in deep concentration, reflecting the nonroutine nature of their task. The Free Hospital The outpatient facilities at the Free Hospital were not as organized as the Main Hospital's. There was a temporary shelter at the Free Hospital's entrance where patients waited to register. Those who 1) Introduction about this case study

2)Key dimentions of quality in aravind eye hospital

3)your managerial perspective and opinion related to this case study

NB:- the case study is related to Aravind eye hospital

see attached picture

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started