Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Please attach excel spreadsheet screenshots if you're not able to attach the whole spreadsheet. it's critical. In early January 2021, the senior management committee of

Please attach excel spreadsheet screenshots if you're not able to attach the whole spreadsheet. it's critical.

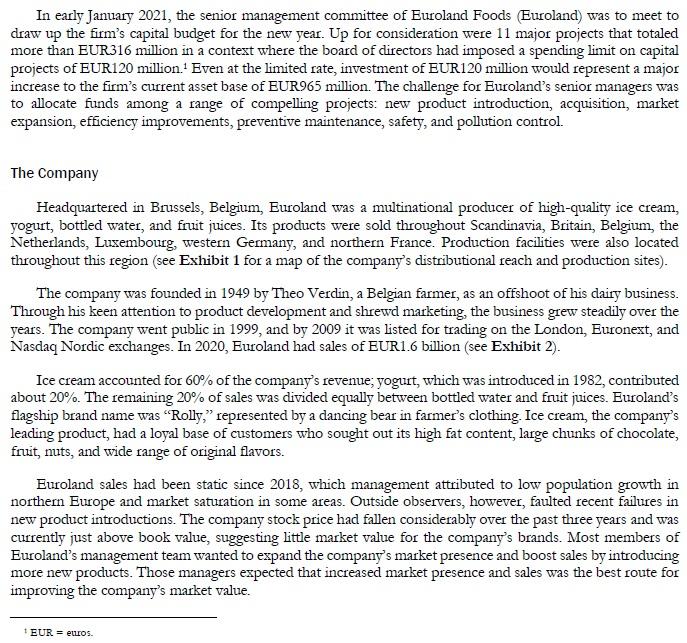

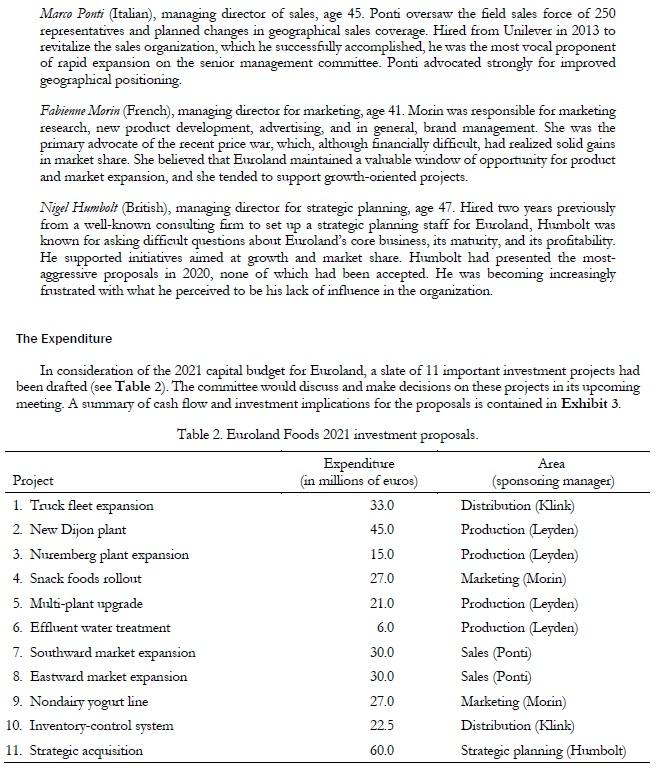

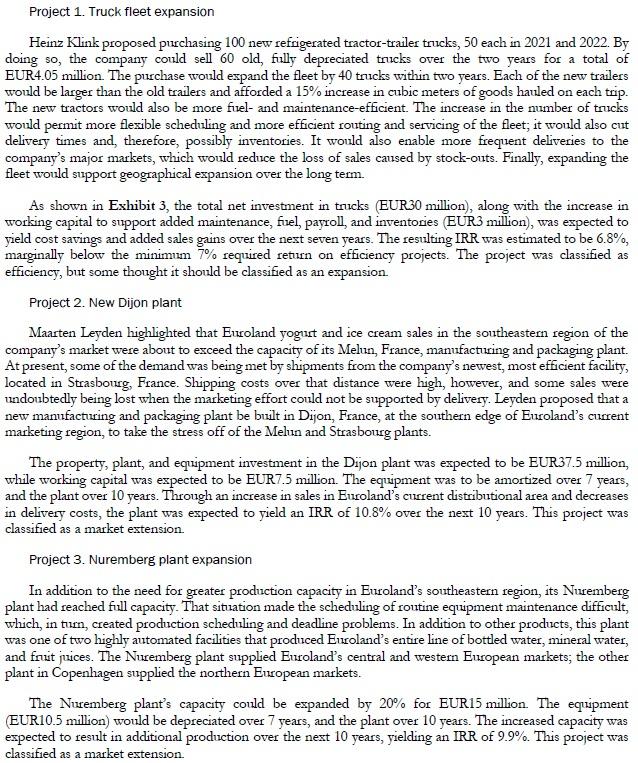

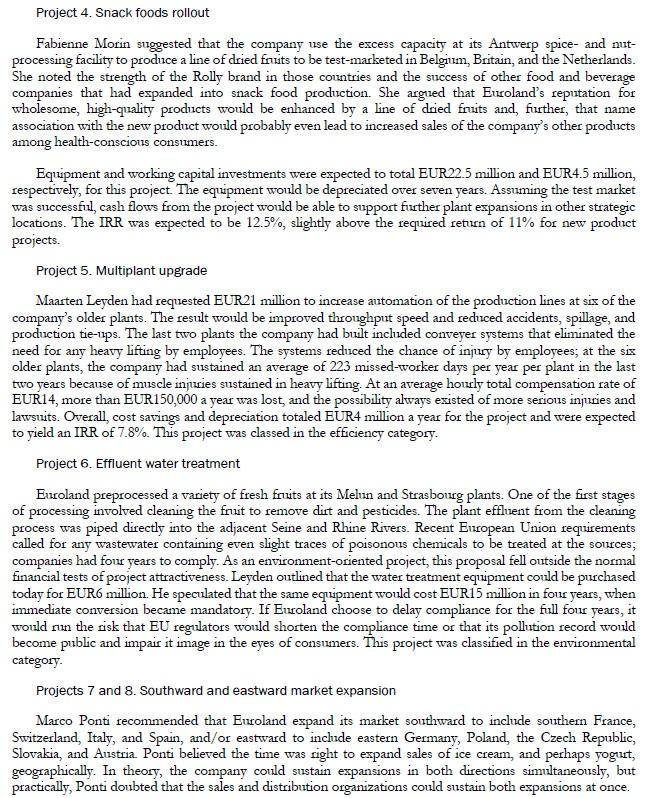

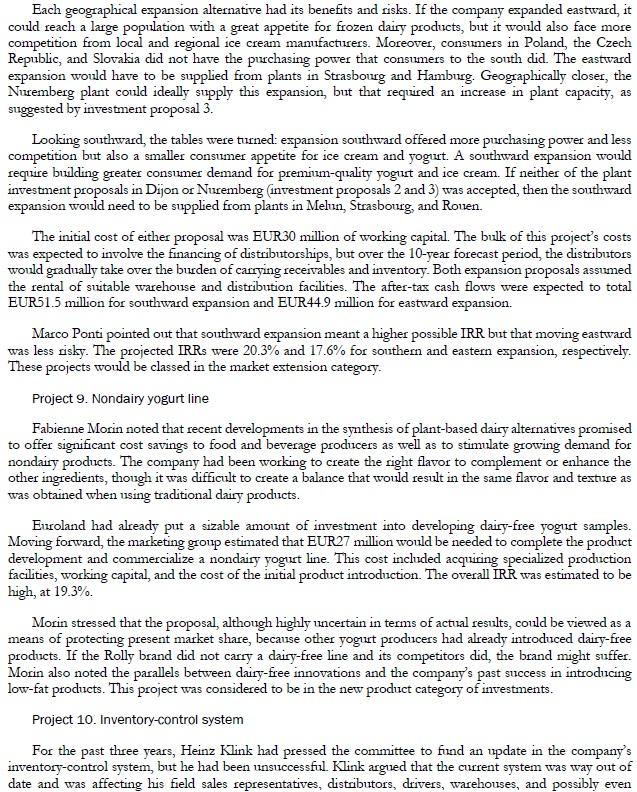

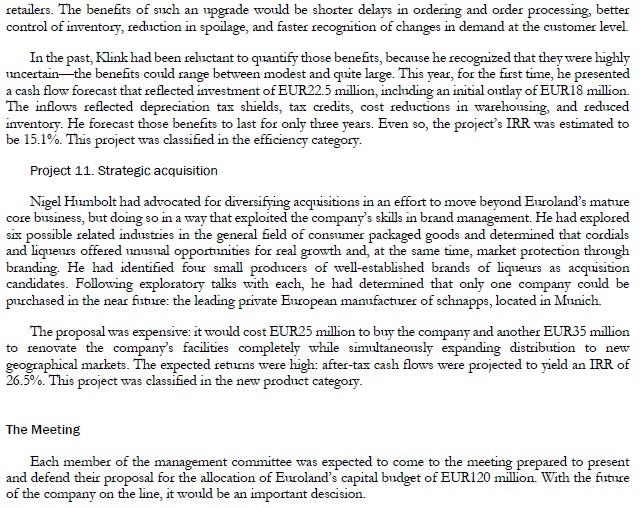

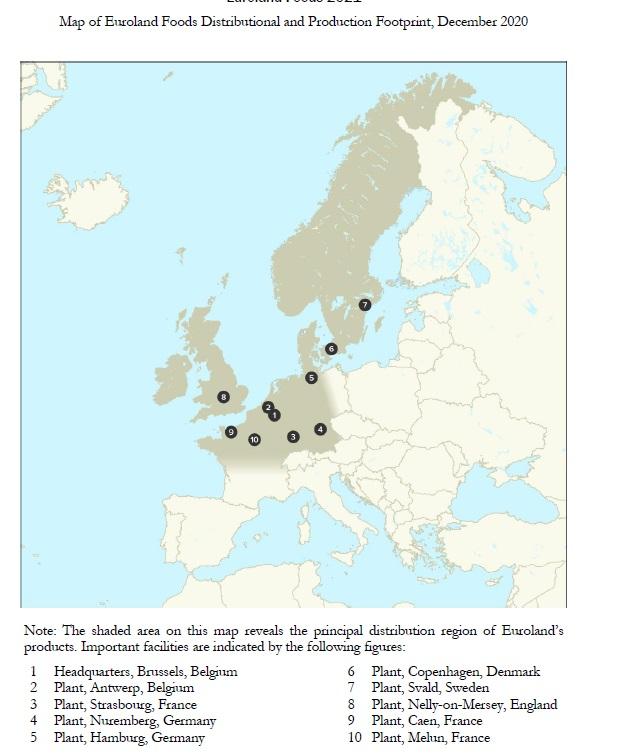

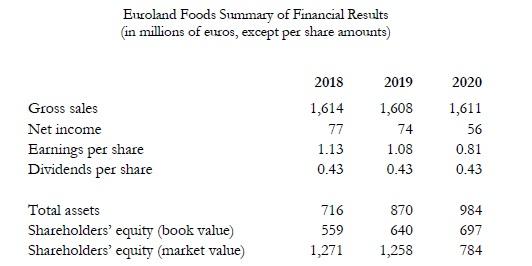

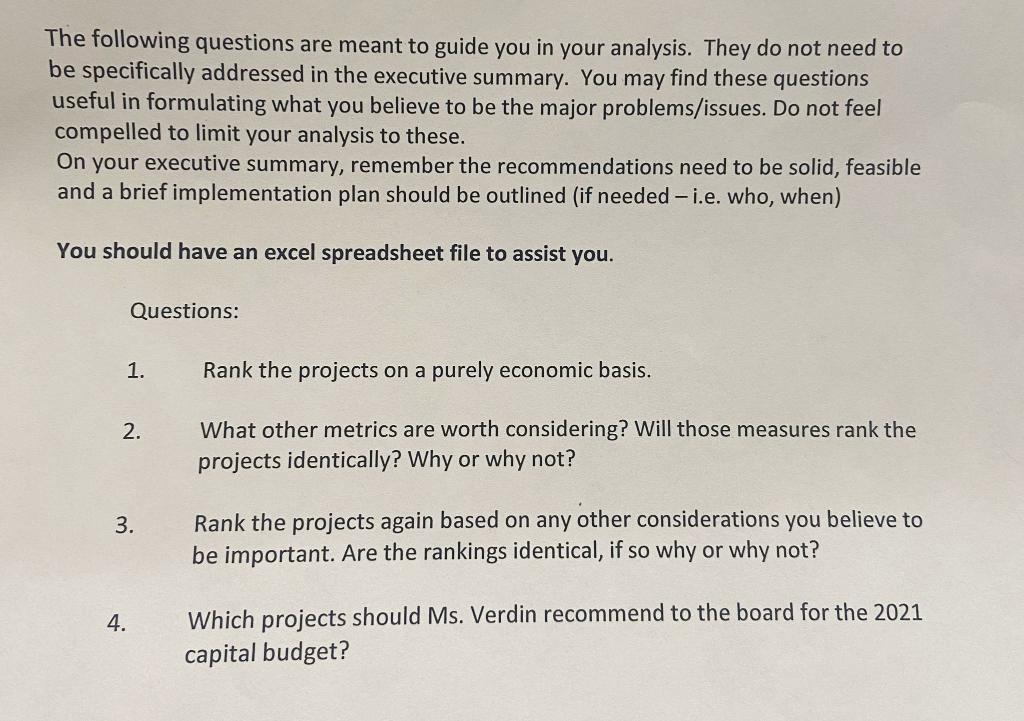

In early January 2021, the senior management committee of Euroland Foods (Euroland) was to meet to draw up the firm's capital budget for the new year. Up for consideration were 11 major projects that totaled more than EUR316 million in a context where the board of directors had imposed a spending limit on capital projects of EUR120 million. 1 Even at the limited rate, investment of EUR120 million would represent a major increase to the firm's current asset base of EUR965 million. The challenge for Euroland's senior managers was to allocate funds among a range of compelling projects: new product introduction, acquisition, market expansion, efficiency improvements, preventive maintenance, safety, and pollution control. The Company Headquartered in Brussels, Belgium, Euroland was a multinational producer of high-quality ice cream, yogurt, bottled water, and fruit juices. Its products were sold throughout Scandinavia, Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western Germany, and northern France. Production facilities were also located throughout this region (see Exhibit 1 for a map of the company's distributional reach and production sites). The company was founded in 1949 by Theo Verdin, a Belgian farmer, as an offshoot of his dairy business. Through his keen attention to product development and shrewd marketing, the business grew steadily over the years. The company went public in 1999, and by 2009 it was listed for trading on the London, Euronext, and Nasdaq Nordic exchanges. In 2020, Euroland had sales of EUR1.6 billion (see Exhibit 2). Ice cream accounted for 60% of the company's revenue; yogurt, which was introduced in 1982, contributed about 20%. The remaining 20% of sales was divided equally between bottled water and fruit juices. Euroland's flagship brand name was "Rolly," represented by a dancing bear in farmer's clothing. Ice cream, the company's leading product, had a loyal base of customers who sought out its high fat content, large chunks of chocolate, fruit, nuts, and wide range of original flavors. Euroland sales had been static since 2018, which management attributed to low population growth in northern Europe and market saturation in some areas. Outside observers, however, faulted recent failures in new product introductions. The company stock price had fallen considerably over the past three years and was currently just above book value, suggesting little market value for the company's brands. Most members of Euroland's management team wanted to expand the company's market presence and boost sales by introducing more new products. Those managers expected that increased market presence and sales was the best route for improving the company's market value. Resource Allocation The capital budget at Euroland was prepared annually by a committee of senior managers, who then presented it for approval to the board of directors. The committee consisted of five managing directors, the prsident directenr-general (PDG), and the finance director. Typically, the PDG solicited investment proposals from the managing directors. Each proposal included a brief project description, a financial analysis, and a discussion of strategic or other qualitative considerations. As a matter of policy, investment proposals at Euroland were subject to two financial hurdles: a payback hurdle and an internal rate of return (IRR) hurdle. The benchmarks for the hurdles varied according to the type of project, as shown in Table 1. These hurdles had been set three years before by the management committee and had not changed since then. Table 1. Euroland Foods investment hurdles. In January 2021, the estimated weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for Euroland was 9.6%. In describing the capital-budgeting process, the finance director, Trudi Lauf, said, We use the sliding scale of IRR tests as a way of recognizing differences in risk among the various types of projects. Where the company takes more risk, we should earn more return. The payback test signals our commitment to high and quick returns. Consistent with investors, we are not prepared for lengthy waits for return on investment. Ownership and the Sentiments of Creditors and Investors Euroland's 12 -member board of directors included three members of the Verdin family, four members of management, and five outside directors who were prominent managers or public figures in northern Europe. Combined, members of the Verdin family owned 20% of Euroland's shares outstanding, and company executives owned 10% of the shares. Venus Asset Management (Venus), a mutual fund management company in London, held 12\%. Banque du Bruges et des Pays Bas (Banque du Bruges) held 9% and had one representative on the board of directors. The remaining 49% of the firm's shares were widely held. The firm's shares traded in Brussels and Frankfurt, Germany. At a debt-to-equity ratio of 125%, Euroland was considerably more leveraged than its peers in the European consumer foods industry. Management had relied on debt financing significantly in the past few years to sustain the firm's capital spending and dividends during a period of price wars initiated by Euroland. Now, with the price wars finished, Euroland's bankers (led by Banque du Bruges) strongly urged an aggressive program of debt reduction. In any event, the bank was not prepared to finance increases in leverage beyond the current level. The president of Banque du Bruges had remarked at a recent board meeting, Restoring some strength to the right-hand side of the balance sheet should now be a first priority. Any expansion of assets should be financed from the cash flow after debt amortization until the debt ratio returns to a more prudent level. If there are crucial investments that cannot be funded this way, then the dividend should be cut. At a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 14 times, shares of Euroland common stock were priced below the average multiples of peer companies and below the average multiples of all companies on the exchanges where Euroland was traded. This was attributable to the recent price wars, which had suppressed Euroland's profitability, and to the company's well-known recent failure to seize significant market share with a new product line of flavored mineral water. Recently, all the major securities houses had been issuing sell recommendations to investors in Euroland shares. Venus had quietly accumulated shares during this period, however, in the expectation of a turnaround in the firm's performance. At the most recent board meeting, the senior managing director of Venus gave a presentation, in which he said, Cutting the dividend is unthinkable, as it would signal a lack of faith in your own future. Selling new shares of stock at this depressed price level is also unthinkable, as it would impose unacceptable dilution on your current shareholders. Euroland equity investors expect an improvement in performance. If that improvement is not forthcoming, or worse, if investors' hopes are dashed, activist investors - with an agenda for change - are likely to seize control at depressed prices. Based on the need to preserve capital, the board of directors had voted unanimously in its most recent meeting to limit capital spending in 2021 to EUR120 million. Members of the Senior Management Committee Seven senior managers of Euroland were tasked with approving the 2021 capital budget. For consideration, each project had to be sponsored by one of the managers present. Usually the decision process included a period of discussion followed by a vote on two to four sets of projects as alternative capital budgets. The various executives who served on the committee were well known to each other: Wilbelmina Verdin (Belgian), PDG, age 57. Granddaughter of the founder and spokesperson on the board of directors for the Verdin family's interests, Verdin had spent her entire career at Euroland, with significant experience in brand management. She was selected as the European Marketer of the Year in 2002 for successfully transforming the company's yogurt and ice cream brands. Verdin was eager to position the company for long-term growth but cautious in the wake of recent difficulties. Trudi Lauf (Swiss), finance director, age 51. Hired from Nestl in 2015 to modernize financial controls and systems, Lauf had been a vocal proponent of reducing leverage on the balance sheet. She frequently voiced stockholders' concerns and frustrations, which had only accelerated with recent investor outcry. Heinz Klink (German), managing director for distribution, age 49. Klink oversaw the transportation, warehousing, and order-fulfillment activities in the company. Having worked at Euroland for 30 years, he was an institutional warrior against spoilage, transport costs, stock-outs, and poor control systems. Maarten Lyden (Dutch), managing director for production and purchasing, age 59. An engineer by training, Leyden managed the production operations at Euroland's 14 plants. He was known as a tough negotiator, especially with unions and suppliers. A fanatic about production cost control, he was not shy about voicing his doubts about the sincerity of creditors' and investors' commitment to the firm. Marco Ponti (Italian), managing director of sales, age 45. Ponti oversaw the field sales force of 250 representatives and planned changes in geographical sales coverage. Hired from Unilever in 2013 to revitalize the sales organization, which he successfully accomplished, he was the most vocal proponent of rapid expansion on the senior management committee. Ponti advocated strongly for improved geographical positioning. Fabienne Morin (French), managing director for marketing, age 41. Morin was responsible for marketing research, new product development, advertising, and in general, brand management. She was the primary advocate of the recent price war, which, although financially difficult, had realized solid gains in market share. She believed that Euroland maintained a valuable window of opportunity for product and market expansion, and she tended to support growth-oriented projects. Nigel Humbolt (British), managing director for strategic planning, age 47. Hired two years previously from a well-known consulting firm to set up a strategic planning staff for Euroland, Humbolt was known for asking difficult questions about Euroland's core business, its maturity, and its profitability. He supported initiatives aimed at growth and market share. Humbolt had presented the mostaggressive proposals in 2020 , none of which had been accepted. He was becoming increasingly frustrated with what he perceived to be his lack of influence in the organization. The Expenditure In consideration of the 2021 capital budget for Euroland, a slate of 11 important investment projects had been drafted (see Table 2). The committee would discuss and make decisions on these projects in its upcoming meeting. A summary of cash flow and investment implications for the proposals is contained in Exhibit 3. Table 2. Euroland Foods 2021 investment proposals. Project 1. Truck fleet expansion Heinz Klink proposed purchasing 100 new refrigerated tractor-trailer trucks, 50 each in 2021 and 2022 . By doing so, the company could sell 60 old, fully depreciated trucks over the two years for a total of EUR4.05 million. The purchase would expand the fleet by 40 trucks within two years. Each of the new trailers would be larger than the old trailers and afforded a 15% increase in cubic meters of goods hauled on each trip. The new tractors would also be more fuel- and maintenance-efficient. The increase in the number of trucks would permit more flexible scheduling and more efficient routing and servicing of the fleet; it would also cut delivery times and, therefore, possibly inventories. It would also enable more frequent deliveries to the company's major markets, which would reduce the loss of sales caused by stock-outs. Finally, expanding the fleet would support geographical expansion over the long term. As shown in Exhibit 3, the total net investment in trucks (EUR 30 million), along with the increase in working capital to support added maintenance, fuel, payroll, and inventocies (EUR3 million), was expected to yield cost savings and added sales gains over the next seven years. The resulting IRR was estimated to be 6.8%, marginally below the minimum 7% required return on efficiency projects. The project was classified as efficiency, but some thought it should be classified as an expansion. Project 2. New Dijon plant Maarten Leyden highlighted that Euroland yogurt and ice cream sales in the southeastern region of the company's market were about to exceed the capacity of its Melun, France, manufacturing and packaging plant. At present, some of the demand was being met by shipments from the company's newest, most efficient facility, located in Strasbourg, France. Shipping costs over that distance were high, however, and some sales were undoubtedly being lost when the marketing effort could not be supported by delivery. Leyden proposed that a new manufacturing and packaging plant be built in Dijon, France, at the southern edge of Euroland's current marketing region, to take the stress off of the Melun and Strasbourg plants. The property, plant, and equipment investment in the Dijon plant was expected to be EUR 37.5 million, while working capital was expected to be EUR 7.5 million. The equipment was to be amortized over 7 years, and the plant over 10 years. Through an increase in sales in Euroland's current distributional area and decreases in delivery costs, the plant was expected to yield an IRR of 10.8% over the next 10 years. This project was classified as a market extension. Project 3. Nuremberg plant expansion In addition to the need for greater production capacity in Euroland's southeastern region, its Nuremberg plant had reached full capacity. That situation made the scheduling of routine equipment maintenance difficult, which, in turn, created production scheduling and deadline problems. In addition to other products, this plant was one of two highly automated facilities that produced Euroland's entire line of bottled water, mineral water, and fruit juices. The Nuremberg plant supplied Euroland's central and western European markets; the other plant in Copenhagen supplied the northern European markets. The Nuremberg plant's capacity could be expanded by 20% for EUR15 million. The equipment (EUR10.5 million) would be depreciated over 7 years, and the plant over 10 years. The increased capacity was expected to result in additional production over the next 10 years, yielding an IRR of 9.9%. This project was classified as a market extension. Project 4. Snack foods rollout Fabienne Morin suggested that the company use the excess capacity at its Antwerp spice- and nutprocessing facility to produce a line of dried fruits to be test-marketed in Belgivm, Britain, and the Netherlands. She noted the strength of the Rolly brand in those countries and the success of other food and beverage companies that had expanded into snack food production. She argued that Euroland's reputation for wholesome, high-quality products would be enhanced by a line of dried fruits and, further, that name association with the new product would probably even lead to increased sales of the company's other products among health-conscious consumers. Equipment and working capital investments were expected to total EUR22.5 million and EUR4.5 million, respectively, for this project. The equipment would be depreciated over seven years. Assuming the test market was successful, cash flows from the project would be able to support further plant expansions in other strategic locations. The IRR was expected to be 12.5%, slightly above the required return of 11% for new product projects. Project 5. Multiplant upgrade Maarten Leyden had requested EUR 21 million to increase automation of the production lines at six of the company's older plants. The result would be improved throughput speed and reduced accidents, spillage, and production tie-ups. The last two plants the company had built included conveyer systems that eliminated the need for any heavy lifting by employees. The systems reduced the chance of injury by employees; at the six older plants, the company had sustained an average of 223 missed-worker days per year per plant in the last two years because of muscle injuries sustained in heavy lifting. At an average hourly total compensation rate of EUR14, more than EUR150,000 a year was lost, and the possibility always existed of more serious injuries and lawsuits. Overall, cost savings and depreciation totaled EUR4 million a year for the project and were expected to yield an IRR of 7.8%. This project was classed in the efficiency category. Project 6 . Effluent water treatment Euroland preprocessed a variety of fresh fruits at its Melun and Strasbourg plants. One of the first stages of processing involved cleaning the fruit to remove dirt and pesticides. The plant effluent from the cleaning process was piped directly into the adjacent Seine and Rhine Rivers. Recent European Union requirements called for any wastewater containing even slight traces of poisonous chemicals to be treated at the sources; companies had four years to comply. As an environment-oriented project, this proposal fell outside the normal Financial tests of project attractiveness. Leyden outlined that the water treatment equipment could be purchased today for EUR6 million. He speculated that the same equipment would cost EUR15 million in four years, when immediate conversion became mandatory. If Euroland choose to delay compliance for the full four years, it would run the risk that EU regulators would shorten the compliance time or that its pollution record would become public and impair it image in the eyes of consumers. This project was classified in the environmental category. Projects 7 and 8 . Southward and eastward market expansion Marco Ponti recommended that Euroland expand its market southward to include southern France, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain, and/or eastward to include eastern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Austria. Ponti believed the time was right to expand sales of ice cream, and perhaps yogurt, geographically. In theory, the company could sustain expansions in both directions simultaneously, but practically, Ponti doubted that the sales and distribution organizations could sustain both expansions at once. Each geographical expansion alternative had its benefits and risks. If the company expanded eastward, it could reach a large population with a great appetite for frozen dairy products, but it would also face more competition from local and regional ice cream manufacturers. Moreover, consumers in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia did not have the purchasing power that consumers to the south did. The eastward expansion would have to be supplied from plants in Strasbourg and Hamburg. Geographically closer, the Nuremberg plant could ideally supply this expansion, but that required an increase in plant capacity, as suggested by investment proposal 3 . Looking southward, the tables were turned: expansion southward offered more purchasing power and less competition but also a smaller consumer appetite for ice cream and yogurt. A southward expansion would require building greater consumer demand for premium-quality yogut and ice cream. If neither of the plant investment proposals in Dijon or Nuremberg (investment proposals 2 and 3) was accepted, then the southward expansion would need to be supplied from plants in Melun, Strasbourg, and Rouen. The initial cost of either proposal was EUR 30 million of working capital. The bulk of this project's costs was expected to involve the financing of distributorships, but over the 10 -year forecast period, the distributors would gradually take over the burden of carrying receivables and inventory. Both expansion proposals assumed the rental of suitable warehouse and distribution facilities. The after-tax cash flows were expected to total EUR51.5 million for southward expansion and EUR44.9 million for eastward expansion. Marco Ponti pointed out that southward expansion meant a higher possible IRR but that moving eastward was less risky. The projected IRRs were 20.3% and 17.6% for southern and eastern expansion, respectively. These projects would be classed in the market extension category. Project 9 . Nondairy yogurt line Fabienne Morin noted that recent developments in the synthesis of plant-based dairy alternatives promised to offer significant cost savings to food and beverage producers as well as to stimulate growing demand for nondairy products. The company had been working to create the right flavor to complement or enhance the other ingredients, though it was difficult to create a balance that would result in the same flavor and texture as was obtained when using traditional dairy products. Euroland had already put a sizable amount of investment into developing dairy-free yogurt samples. Moving forward, the marketing group estimated that EUR27 million would be needed to complete the product development and commercialize a nondairy yogurt line. This cost included acquiring specialized production facilities, working capital, and the cost of the initial product introduction. The overall IRR was estimated to be high, at 19.3%. Morin stressed that the proposal, although highly uncertain in terms of actual results, could be viewed as a means of protecting present market share, because other yogurt producers had already introduced dairy-free products. If the Rolly brand did not carry a dairy-free line and its competitors did, the brand might suffer. Morin also noted the parallels between dairy-free innovations and the company's past success in introducing low-fat products. This project was considered to be in the new product category of investments. Project 10. Inventory-control system For the past three years, Heinz Klink had pressed the committee to fund an update in the company's inventory-control system, but he had been unsuccessful. Klink argued that the current system was way out of date and was affecting his field sales representatives, distributors, drivers, warehouses, and possibly even retalers. The benetits of sich an upgrade would be shorter delays in ordering and order processing, better control of inventory, reduction in spoilage, and faster recognition of changes in demand at the customer level. In the past, Klink had been reluctant to quantify those benefits, because he recognized that they were highly uncertain - the benefits could range between modest and quite large. This year, for the first time, he presented a cash flow forecast that reflected investment of EUR 22.5 million, including an initial outlay of EUR18 million. The inflows reflected depreciation tax shields, tax credits, cost reductions in warehousing, and reduced inventory. He forecast those benefits to last for only three years. Even so, the project's IRR was estimated to be 15.1%. This project was classified in the efficiency category. Project 11. Strategic acquisition Nigel Humbolt had advocated for diversifying acquisitions in an effort to move beyond Euroland's mature core business, but doing so in a way that exploited the company's skills in brand management. He had explored six possible related industries in the general field of consumer packaged goods and determined that cordials and liqueurs offered unusual opportunities for real growth and, at the same time, market protection through branding. He had identified four small producers of well-established brands of liqueurs as acquisition candidates. Following exploratory talks with each, he had determined that only one company could be purchased in the near future: the leading private European manufacturer of schnapps, located in Munich. The proposal was expensive: it would cost EUR2 5 million to buy the company and another EUR 35 million to renovate the company's facilities completely while simultaneously expanding distribution to new geographical markets. The expected returns were high: after-tax cash flows were projected to yield an IRR of 26.5%. This project was classified in the new product category. The Meeting Each member of the management committee was expected to come to the meeting prepared to present and defend their proposal for the allocation of Euroland's capital budget of EUR120 million. With the future of the company on the line, it would be an important descision. Map of Euroland Foods Distributional and Production Footprint, December 2020 Note: The shaded area on this map reveals the principal distribution region of Euroland's products. Important facilities are indicated by the following figures: 12345Headquarters,Brussels,BelgiumPlant,Antwerp,BelgiumPlant,Strasbourg,FrancePlant,Nuremberg,GermanyPlant,Hamburg,Germany678910Plant,Melun,FrancePlant,Copenhagen,DenmarkPlant,Svald,SwedenPlant,Nelly-on-Mersey,EnglandPlant,Caen,France Euroland Foods Summary of Financial Results (in millions of euros, except per share amounts) Free Cash Flows and Analysis of Proposed Projects (monetary values in millions of euros) 1. The effluent treatment program is not included in this exhibit. 2. The total investment reflects both the initial and subsequent investment requirements. For example, the EUR.33 million investment requirement for Project 1 , the truck fleet expansion, includes EUR17.1 million spent in the initial year and EUR.15.9 million spent in the following year. 3. Free cash flow is defined as incremental profit or cost savings after taxes + depreciation - investment in fixed assets and working capital. 4. Franchisees in the southward or eastward expansion would gradually take over the burden of carrying receivables and inventory. 5. For the strategic acquisition, EUR25 million would be spent in the first year, EUR.30 million in the second, and EUR5 million in the third. The following questions are meant to guide you in your analysis. They do not need to be specifically addressed in the executive summary. You may find these questions useful in formulating what you believe to be the major problems/issues. Do not feel compelled to limit your analysis to these. On your executive summary, remember the recommendations need to be solid, feasible and a brief implementation plan should be outlined (if needed-i.e. who, when) You should have an excel spreadsheet file to assist you. Questions: 1. Rank the projects on a purely economic basis. 2. What other metrics are worth considering? Will those measures rank the projects identically? Why or why not? 3. Rank the projects again based on any other considerations you believe to be important. Are the rankings identical, if so why or why not? 4. Which projects should Ms. Verdin recommend to the board for the 2021 capital budget? In early January 2021, the senior management committee of Euroland Foods (Euroland) was to meet to draw up the firm's capital budget for the new year. Up for consideration were 11 major projects that totaled more than EUR316 million in a context where the board of directors had imposed a spending limit on capital projects of EUR120 million. 1 Even at the limited rate, investment of EUR120 million would represent a major increase to the firm's current asset base of EUR965 million. The challenge for Euroland's senior managers was to allocate funds among a range of compelling projects: new product introduction, acquisition, market expansion, efficiency improvements, preventive maintenance, safety, and pollution control. The Company Headquartered in Brussels, Belgium, Euroland was a multinational producer of high-quality ice cream, yogurt, bottled water, and fruit juices. Its products were sold throughout Scandinavia, Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western Germany, and northern France. Production facilities were also located throughout this region (see Exhibit 1 for a map of the company's distributional reach and production sites). The company was founded in 1949 by Theo Verdin, a Belgian farmer, as an offshoot of his dairy business. Through his keen attention to product development and shrewd marketing, the business grew steadily over the years. The company went public in 1999, and by 2009 it was listed for trading on the London, Euronext, and Nasdaq Nordic exchanges. In 2020, Euroland had sales of EUR1.6 billion (see Exhibit 2). Ice cream accounted for 60% of the company's revenue; yogurt, which was introduced in 1982, contributed about 20%. The remaining 20% of sales was divided equally between bottled water and fruit juices. Euroland's flagship brand name was "Rolly," represented by a dancing bear in farmer's clothing. Ice cream, the company's leading product, had a loyal base of customers who sought out its high fat content, large chunks of chocolate, fruit, nuts, and wide range of original flavors. Euroland sales had been static since 2018, which management attributed to low population growth in northern Europe and market saturation in some areas. Outside observers, however, faulted recent failures in new product introductions. The company stock price had fallen considerably over the past three years and was currently just above book value, suggesting little market value for the company's brands. Most members of Euroland's management team wanted to expand the company's market presence and boost sales by introducing more new products. Those managers expected that increased market presence and sales was the best route for improving the company's market value. Resource Allocation The capital budget at Euroland was prepared annually by a committee of senior managers, who then presented it for approval to the board of directors. The committee consisted of five managing directors, the prsident directenr-general (PDG), and the finance director. Typically, the PDG solicited investment proposals from the managing directors. Each proposal included a brief project description, a financial analysis, and a discussion of strategic or other qualitative considerations. As a matter of policy, investment proposals at Euroland were subject to two financial hurdles: a payback hurdle and an internal rate of return (IRR) hurdle. The benchmarks for the hurdles varied according to the type of project, as shown in Table 1. These hurdles had been set three years before by the management committee and had not changed since then. Table 1. Euroland Foods investment hurdles. In January 2021, the estimated weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for Euroland was 9.6%. In describing the capital-budgeting process, the finance director, Trudi Lauf, said, We use the sliding scale of IRR tests as a way of recognizing differences in risk among the various types of projects. Where the company takes more risk, we should earn more return. The payback test signals our commitment to high and quick returns. Consistent with investors, we are not prepared for lengthy waits for return on investment. Ownership and the Sentiments of Creditors and Investors Euroland's 12 -member board of directors included three members of the Verdin family, four members of management, and five outside directors who were prominent managers or public figures in northern Europe. Combined, members of the Verdin family owned 20% of Euroland's shares outstanding, and company executives owned 10% of the shares. Venus Asset Management (Venus), a mutual fund management company in London, held 12\%. Banque du Bruges et des Pays Bas (Banque du Bruges) held 9% and had one representative on the board of directors. The remaining 49% of the firm's shares were widely held. The firm's shares traded in Brussels and Frankfurt, Germany. At a debt-to-equity ratio of 125%, Euroland was considerably more leveraged than its peers in the European consumer foods industry. Management had relied on debt financing significantly in the past few years to sustain the firm's capital spending and dividends during a period of price wars initiated by Euroland. Now, with the price wars finished, Euroland's bankers (led by Banque du Bruges) strongly urged an aggressive program of debt reduction. In any event, the bank was not prepared to finance increases in leverage beyond the current level. The president of Banque du Bruges had remarked at a recent board meeting, Restoring some strength to the right-hand side of the balance sheet should now be a first priority. Any expansion of assets should be financed from the cash flow after debt amortization until the debt ratio returns to a more prudent level. If there are crucial investments that cannot be funded this way, then the dividend should be cut. At a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 14 times, shares of Euroland common stock were priced below the average multiples of peer companies and below the average multiples of all companies on the exchanges where Euroland was traded. This was attributable to the recent price wars, which had suppressed Euroland's profitability, and to the company's well-known recent failure to seize significant market share with a new product line of flavored mineral water. Recently, all the major securities houses had been issuing sell recommendations to investors in Euroland shares. Venus had quietly accumulated shares during this period, however, in the expectation of a turnaround in the firm's performance. At the most recent board meeting, the senior managing director of Venus gave a presentation, in which he said, Cutting the dividend is unthinkable, as it would signal a lack of faith in your own future. Selling new shares of stock at this depressed price level is also unthinkable, as it would impose unacceptable dilution on your current shareholders. Euroland equity investors expect an improvement in performance. If that improvement is not forthcoming, or worse, if investors' hopes are dashed, activist investors - with an agenda for change - are likely to seize control at depressed prices. Based on the need to preserve capital, the board of directors had voted unanimously in its most recent meeting to limit capital spending in 2021 to EUR120 million. Members of the Senior Management Committee Seven senior managers of Euroland were tasked with approving the 2021 capital budget. For consideration, each project had to be sponsored by one of the managers present. Usually the decision process included a period of discussion followed by a vote on two to four sets of projects as alternative capital budgets. The various executives who served on the committee were well known to each other: Wilbelmina Verdin (Belgian), PDG, age 57. Granddaughter of the founder and spokesperson on the board of directors for the Verdin family's interests, Verdin had spent her entire career at Euroland, with significant experience in brand management. She was selected as the European Marketer of the Year in 2002 for successfully transforming the company's yogurt and ice cream brands. Verdin was eager to position the company for long-term growth but cautious in the wake of recent difficulties. Trudi Lauf (Swiss), finance director, age 51. Hired from Nestl in 2015 to modernize financial controls and systems, Lauf had been a vocal proponent of reducing leverage on the balance sheet. She frequently voiced stockholders' concerns and frustrations, which had only accelerated with recent investor outcry. Heinz Klink (German), managing director for distribution, age 49. Klink oversaw the transportation, warehousing, and order-fulfillment activities in the company. Having worked at Euroland for 30 years, he was an institutional warrior against spoilage, transport costs, stock-outs, and poor control systems. Maarten Lyden (Dutch), managing director for production and purchasing, age 59. An engineer by training, Leyden managed the production operations at Euroland's 14 plants. He was known as a tough negotiator, especially with unions and suppliers. A fanatic about production cost control, he was not shy about voicing his doubts about the sincerity of creditors' and investors' commitment to the firm. Marco Ponti (Italian), managing director of sales, age 45. Ponti oversaw the field sales force of 250 representatives and planned changes in geographical sales coverage. Hired from Unilever in 2013 to revitalize the sales organization, which he successfully accomplished, he was the most vocal proponent of rapid expansion on the senior management committee. Ponti advocated strongly for improved geographical positioning. Fabienne Morin (French), managing director for marketing, age 41. Morin was responsible for marketing research, new product development, advertising, and in general, brand management. She was the primary advocate of the recent price war, which, although financially difficult, had realized solid gains in market share. She believed that Euroland maintained a valuable window of opportunity for product and market expansion, and she tended to support growth-oriented projects. Nigel Humbolt (British), managing director for strategic planning, age 47. Hired two years previously from a well-known consulting firm to set up a strategic planning staff for Euroland, Humbolt was known for asking difficult questions about Euroland's core business, its maturity, and its profitability. He supported initiatives aimed at growth and market share. Humbolt had presented the mostaggressive proposals in 2020 , none of which had been accepted. He was becoming increasingly frustrated with what he perceived to be his lack of influence in the organization. The Expenditure In consideration of the 2021 capital budget for Euroland, a slate of 11 important investment projects had been drafted (see Table 2). The committee would discuss and make decisions on these projects in its upcoming meeting. A summary of cash flow and investment implications for the proposals is contained in Exhibit 3. Table 2. Euroland Foods 2021 investment proposals. Project 1. Truck fleet expansion Heinz Klink proposed purchasing 100 new refrigerated tractor-trailer trucks, 50 each in 2021 and 2022 . By doing so, the company could sell 60 old, fully depreciated trucks over the two years for a total of EUR4.05 million. The purchase would expand the fleet by 40 trucks within two years. Each of the new trailers would be larger than the old trailers and afforded a 15% increase in cubic meters of goods hauled on each trip. The new tractors would also be more fuel- and maintenance-efficient. The increase in the number of trucks would permit more flexible scheduling and more efficient routing and servicing of the fleet; it would also cut delivery times and, therefore, possibly inventories. It would also enable more frequent deliveries to the company's major markets, which would reduce the loss of sales caused by stock-outs. Finally, expanding the fleet would support geographical expansion over the long term. As shown in Exhibit 3, the total net investment in trucks (EUR 30 million), along with the increase in working capital to support added maintenance, fuel, payroll, and inventocies (EUR3 million), was expected to yield cost savings and added sales gains over the next seven years. The resulting IRR was estimated to be 6.8%, marginally below the minimum 7% required return on efficiency projects. The project was classified as efficiency, but some thought it should be classified as an expansion. Project 2. New Dijon plant Maarten Leyden highlighted that Euroland yogurt and ice cream sales in the southeastern region of the company's market were about to exceed the capacity of its Melun, France, manufacturing and packaging plant. At present, some of the demand was being met by shipments from the company's newest, most efficient facility, located in Strasbourg, France. Shipping costs over that distance were high, however, and some sales were undoubtedly being lost when the marketing effort could not be supported by delivery. Leyden proposed that a new manufacturing and packaging plant be built in Dijon, France, at the southern edge of Euroland's current marketing region, to take the stress off of the Melun and Strasbourg plants. The property, plant, and equipment investment in the Dijon plant was expected to be EUR 37.5 million, while working capital was expected to be EUR 7.5 million. The equipment was to be amortized over 7 years, and the plant over 10 years. Through an increase in sales in Euroland's current distributional area and decreases in delivery costs, the plant was expected to yield an IRR of 10.8% over the next 10 years. This project was classified as a market extension. Project 3. Nuremberg plant expansion In addition to the need for greater production capacity in Euroland's southeastern region, its Nuremberg plant had reached full capacity. That situation made the scheduling of routine equipment maintenance difficult, which, in turn, created production scheduling and deadline problems. In addition to other products, this plant was one of two highly automated facilities that produced Euroland's entire line of bottled water, mineral water, and fruit juices. The Nuremberg plant supplied Euroland's central and western European markets; the other plant in Copenhagen supplied the northern European markets. The Nuremberg plant's capacity could be expanded by 20% for EUR15 million. The equipment (EUR10.5 million) would be depreciated over 7 years, and the plant over 10 years. The increased capacity was expected to result in additional production over the next 10 years, yielding an IRR of 9.9%. This project was classified as a market extension. Project 4. Snack foods rollout Fabienne Morin suggested that the company use the excess capacity at its Antwerp spice- and nutprocessing facility to produce a line of dried fruits to be test-marketed in Belgivm, Britain, and the Netherlands. She noted the strength of the Rolly brand in those countries and the success of other food and beverage companies that had expanded into snack food production. She argued that Euroland's reputation for wholesome, high-quality products would be enhanced by a line of dried fruits and, further, that name association with the new product would probably even lead to increased sales of the company's other products among health-conscious consumers. Equipment and working capital investments were expected to total EUR22.5 million and EUR4.5 million, respectively, for this project. The equipment would be depreciated over seven years. Assuming the test market was successful, cash flows from the project would be able to support further plant expansions in other strategic locations. The IRR was expected to be 12.5%, slightly above the required return of 11% for new product projects. Project 5. Multiplant upgrade Maarten Leyden had requested EUR 21 million to increase automation of the production lines at six of the company's older plants. The result would be improved throughput speed and reduced accidents, spillage, and production tie-ups. The last two plants the company had built included conveyer systems that eliminated the need for any heavy lifting by employees. The systems reduced the chance of injury by employees; at the six older plants, the company had sustained an average of 223 missed-worker days per year per plant in the last two years because of muscle injuries sustained in heavy lifting. At an average hourly total compensation rate of EUR14, more than EUR150,000 a year was lost, and the possibility always existed of more serious injuries and lawsuits. Overall, cost savings and depreciation totaled EUR4 million a year for the project and were expected to yield an IRR of 7.8%. This project was classed in the efficiency category. Project 6 . Effluent water treatment Euroland preprocessed a variety of fresh fruits at its Melun and Strasbourg plants. One of the first stages of processing involved cleaning the fruit to remove dirt and pesticides. The plant effluent from the cleaning process was piped directly into the adjacent Seine and Rhine Rivers. Recent European Union requirements called for any wastewater containing even slight traces of poisonous chemicals to be treated at the sources; companies had four years to comply. As an environment-oriented project, this proposal fell outside the normal Financial tests of project attractiveness. Leyden outlined that the water treatment equipment could be purchased today for EUR6 million. He speculated that the same equipment would cost EUR15 million in four years, when immediate conversion became mandatory. If Euroland choose to delay compliance for the full four years, it would run the risk that EU regulators would shorten the compliance time or that its pollution record would become public and impair it image in the eyes of consumers. This project was classified in the environmental category. Projects 7 and 8 . Southward and eastward market expansion Marco Ponti recommended that Euroland expand its market southward to include southern France, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain, and/or eastward to include eastern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Austria. Ponti believed the time was right to expand sales of ice cream, and perhaps yogurt, geographically. In theory, the company could sustain expansions in both directions simultaneously, but practically, Ponti doubted that the sales and distribution organizations could sustain both expansions at once. Each geographical expansion alternative had its benefits and risks. If the company expanded eastward, it could reach a large population with a great appetite for frozen dairy products, but it would also face more competition from local and regional ice cream manufacturers. Moreover, consumers in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia did not have the purchasing power that consumers to the south did. The eastward expansion would have to be supplied from plants in Strasbourg and Hamburg. Geographically closer, the Nuremberg plant could ideally supply this expansion, but that required an increase in plant capacity, as suggested by investment proposal 3 . Looking southward, the tables were turned: expansion southward offered more purchasing power and less competition but also a smaller consumer appetite for ice cream and yogurt. A southward expansion would require building greater consumer demand for premium-quality yogut and ice cream. If neither of the plant investment proposals in Dijon or Nuremberg (investment proposals 2 and 3) was accepted, then the southward expansion would need to be supplied from plants in Melun, Strasbourg, and Rouen. The initial cost of either proposal was EUR 30 million of working capital. The bulk of this project's costs was expected to involve the financing of distributorships, but over the 10 -year forecast period, the distributors would gradually take over the burden of carrying receivables and inventory. Both expansion proposals assumed the rental of suitable warehouse and distribution facilities. The after-tax cash flows were expected to total EUR51.5 million for southward expansion and EUR44.9 million for eastward expansion. Marco Ponti pointed out that southward expansion meant a higher possible IRR but that moving eastward was less risky. The projected IRRs were 20.3% and 17.6% for southern and eastern expansion, respectively. These projects would be classed in the market extension category. Project 9 . Nondairy yogurt line Fabienne Morin noted that recent developments in the synthesis of plant-based dairy alternatives promised to offer significant cost savings to food and beverage producers as well as to stimulate growing demand for nondairy products. The company had been working to create the right flavor to complement or enhance the other ingredients, though it was difficult to create a balance that would result in the same flavor and texture as was obtained when using traditional dairy products. Euroland had already put a sizable amount of investment into developing dairy-free yogurt samples. Moving forward, the marketing group estimated that EUR27 million would be needed to complete the product development and commercialize a nondairy yogurt line. This cost included acquiring specialized production facilities, working capital, and the cost of the initial product introduction. The overall IRR was estimated to be high, at 19.3%. Morin stressed that the proposal, although highly uncertain in terms of actual results, could be viewed as a means of protecting present market share, because other yogurt producers had already introduced dairy-free products. If the Rolly brand did not carry a dairy-free line and its competitors did, the brand might suffer. Morin also noted the parallels between dairy-free innovations and the company's past success in introducing low-fat products. This project was considered to be in the new product category of investments. Project 10. Inventory-control system For the past three years, Heinz Klink had pressed the committee to fund an update in the company's inventory-control system, but he had been unsuccessful. Klink argued that the current system was way out of date and was affecting his field sales representatives, distributors, drivers, warehouses, and possibly even retalers. The benetits of sich an upgrade would be shorter delays in ordering and order processing, better control of inventory, reduction in spoilage, and faster recognition of changes in demand at the customer level. In the past, Klink had been reluctant to quantify those benefits, because he recognized that they were highly uncertain - the benefits could range between modest and quite large. This year, for the first time, he presented a cash flow forecast that reflected investment of EUR 22.5 million, including an initial outlay of EUR18 million. The inflows reflected depreciation tax shields, tax credits, cost reductions in warehousing, and reduced inventory. He forecast those benefits to last for only three years. Even so, the project's IRR was estimated to be 15.1%. This project was classified in the efficiency category. Project 11. Strategic acquisition Nigel Humbolt had advocated for diversifying acquisitions in an effort to move beyond Euroland's mature core business, but doing so in a way that exploited the company's skills in brand management. He had explored six possible related industries in the general field of consumer packaged goods and determined that cordials and liqueurs offered unusual opportunities for real growth and, at the same time, market protection through branding. He had identified four small producers of well-established brands of liqueurs as acquisition candidates. Following exploratory talks with each, he had determined that only one company could be purchased in the near future: the leading private European manufacturer of schnapps, located in Munich. The proposal was expensive: it would cost EUR2 5 million to buy the company and another EUR 35 million to renovate the company's facilities completely while simultaneously expanding distribution to new geographical markets. The expected returns were high: after-tax cash flows were projected to yield an IRR of 26.5%. This project was classified in the new product category. The Meeting Each member of the management committee was expected to come to the meeting prepared to present and defend their proposal for the allocation of Euroland's capital budget of EUR120 million. With the future of the company on the line, it would be an important descision. Map of Euroland Foods Distributional and Production Footprint, December 2020 Note: The shaded area on this map reveals the principal distribution region of Euroland's products. Important facilities are indicated by the following figures: 12345Headquarters,Brussels,BelgiumPlant,Antwerp,BelgiumPlant,Strasbourg,FrancePlant,Nuremberg,GermanyPlant,Hamburg,Germany678910Plant,Melun,FrancePlant,Copenhagen,DenmarkPlant,Svald,SwedenPlant,Nelly-on-Mersey,EnglandPlant,Caen,France Euroland Foods Summary of Financial Results (in millions of euros, except per share amounts) Free Cash Flows and Analysis of Proposed Projects (monetary values in millions of euros) 1. The effluent treatment program is not included in this exhibit. 2. The total investment reflects both the initial and subsequent investment requirements. For example, the EUR.33 million investment requirement for Project 1 , the truck fleet expansion, includes EUR17.1 million spent in the initial year and EUR.15.9 million spent in the following year. 3. Free cash flow is defined as incremental profit or cost savings after taxes + depreciation - investment in fixed assets and working capital. 4. Franchisees in the southward or eastward expansion would gradually take over the burden of carrying receivables and inventory. 5. For the strategic acquisition, EUR25 million would be spent in the first year, EUR.30 million in the second, and EUR5 million in the third. The following questions are meant to guide you in your analysis. They do not need to be specifically addressed in the executive summary. You may find these questions useful in formulating what you believe to be the major problems/issues. Do not feel compelled to limit your analysis to these. On your executive summary, remember the recommendations need to be solid, feasible and a brief implementation plan should be outlined (if needed-i.e. who, when) You should have an excel spreadsheet file to assist you. Questions: 1. Rank the projects on a purely economic basis. 2. What other metrics are worth considering? Will those measures rank the projects identically? Why or why not? 3. Rank the projects again based on any other considerations you believe to be important. Are the rankings identical, if so why or why not? 4. Which projects should Ms. Verdin recommend to the board for the 2021 capital budgetStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started