Question: Please read the case study below titled Convergence in industrial relations institutions: the emerging Anglo-American model? and help me answer the questions that follow. If

Please read the case study below titled "Convergence in industrial relations institutions: the emerging Anglo-American model?" and help me answer the questions that follow. If possible cite all sources of information and provide references.

- The case study suggests that the Thatcher/Reagan era had significantly contributed to the changing employment relations systems in the two countries. From the case study and other literature, compare the raise or emergence of the two world political leaders. In doing so, list their features in a comparative table before discussing their similarities, differences, advantages and disadvantages to the State as the main actor in employment relations.

- Based on your knowledge, the case study or other literature, compare the actual changes that the two world leaders implemented that significantly contributed to the changing employment relations systems in the two countries. In doing so, list the actual changes that the two leaders implemented before discussing their similarities, differences, advantages and disadvantages to the employees and trade union as the main actor in employment relations.

- The case study recommends that the environment in which employment relations existed in the two countries is capitalist. Compare the two capitalist types mentioned in the case study by listing their features before discussing their similarities, differences, advantages and disadvantages to the employers.

- Specifically, discuss the impacts of the implemented changes that the two world leaders have on other countries as mentioned in the case study.

- Has the implemented changes in the USA and UK and the impacts on Anglo-American countries also been experienced in the country of Fiji? Why?

Case Study

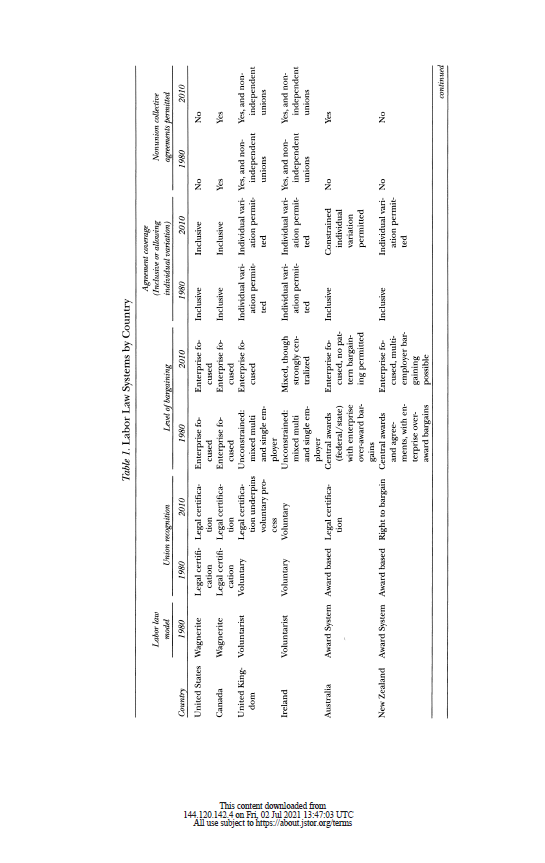

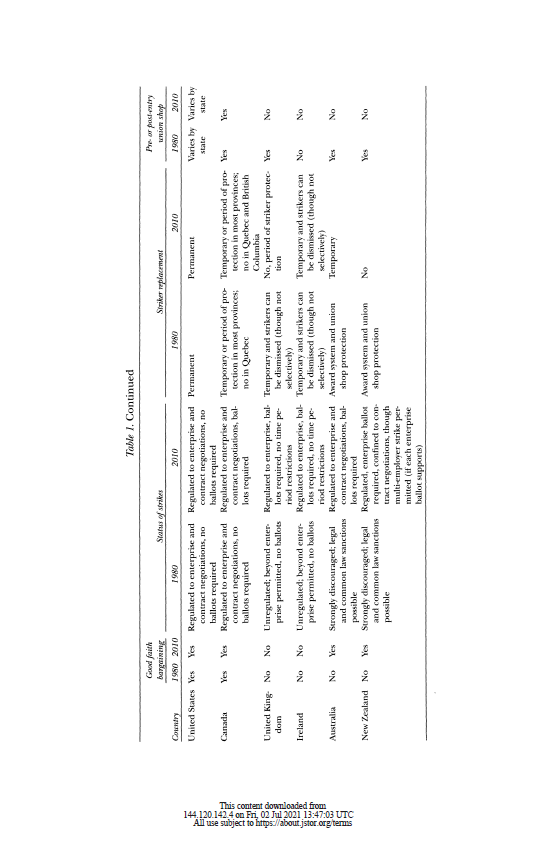

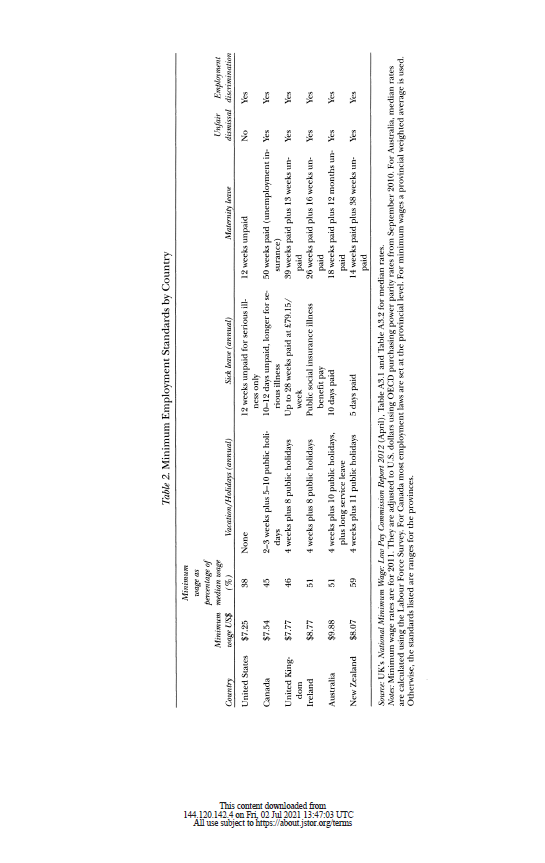

OSAGE CONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS: THE EMERGING ANGLO- AMERICAN MODEL? Author(s): ALEXANDER J. S. COLVIN and OWEN DARBISHIRE Source: ILR Review , October 2013, Vol. 66, No. 5 (October 2013), pp. 1047-1077 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24369571 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support ]stor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms ILR Review Sage Publications, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to ISTOR This content downloaded from 144.120.141.4 on Fri, 02 Jud 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to http::/about jutor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS: THE EMERGING ANGLO-AMERICAN MODEL? ALEXANDER J. S. COLVIN AND OWEN DARBISHIRE* At the outset of the Thatcher/ Reagan era, the employment and labor law systems across six Anglo-American countries could be di- vided into three pairings: the Wagner Act model of the United States and Canada; the Voluntarist system of collective bargaining and strong unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland; and the highly centralized, legalistic Award systems of Australia and New Zealand. The authors argue that there has been growing convergence in two major areas: First, of labor law toward a private ordering of employ- ment relations in which terms and conditions of work and employ- ment are primarily determined at the level of the enterprise; and second, of individual employment rights, toward a basket of mini- mum standards that can then be improved upon by the parties. The greatest similarity is found in Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. Ireland retains a greater degree of public ordering, while the United States diverges in favoring the interests of employers over those of employees and organized labor. The au- thors explore reasons for the convergence. The elections of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom heralded a sea change in a conserva- tive direction in the politics of the Anglo-American countries beginning in the 1980s. A central component of the conservative agenda that these lead- ers ushered in was an effort to reduce the power and influence of labor unions, most famously with Reagan's firing of the air traffic controllers in the 1981 PATCO strike and Thatcher's defeat of the Mineworkers' 1984-85 strike. More broadly, labor union representation density went into a general decline across the Anglo-American countries (in addition to the United States and the United Kingdom, we include Canada, Australia, New Zea- land, and Ireland within this grouping) from the 1980s onward, at varying rates, but with a common downward trajectory. In this article we examine to what degree labor and employment law systems changed similarly during "Alexander J. S. Colvin is a Professor at the ILR School, Cornell University. Owen Darbishire is a Uni- versity Lecturer in the Said Business School, University of Oxford and a Fellow of Pembroke College. For information regarding the data and/ or computer programs utilized for this study, please address corre- pondence to Alex Colvin at ajc22@cornell.edu. I'.RRaving, 66(5), October 2013. @ by Cornell University. Print 0019-7939/Online 2162-271X/00/6605 $05.00 This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org terms1056 ILKREVIEW The Employment Relations Act (ERA) 2000 represented a rebalancing of power in an attempt to remove the neoliberal ideology of the ECA, facilitate union recognition, and build a cooperative employment relationship to achieve a high-wage, high-skill economy (Wilson 2010), An explicit object tive of the Act was the promotion of collective bargaining, while recognizing the inherent inequality of bargaining power in the employment relation- ship. As with the Wagner Act, unions gain exclusive bargaining rights, and enterprise agreements can be reached only with independent unions. Good faith bargaining was introduced and, as extended in 2004, requires that em- ployers reach an agreement in the absence of a "genuine reason, based on reasonable grounds" not to ($33, ERA 2000); has the possibility for terms to be imposed in cases of bad faith; and requires that good faith extend to the ongoing employment relationship with employers prohibited from under- mining unions or collective bargaining. The ERA also prohibits worker re- placement or reassigning existing employees in case of a strike. Nevertheless, the ERA remains entirely consistent with the private order- ing model. Although multi-employer bargaining is permitted, this is not supported by good faith requirements that remain at the enterprise level, while any industrial action has to be authorized independently at every workplace by ballots. Collective agreements cover only union members, can- not be passed on automatically to nonmembers, and individual variation is permitted and prevalent, even against the backdrop of a union agreement. The impact of the ERA has not reversed the decline in union density in New Zealand, which fell from 45% in 1985 to 19% in 2009, with just 9% in the private sector (Blumenfeld 2010: 47). In Australia, the transformation was more gradual, beginning with the 1993 Industrial Relations Reform Act and particularly the 1996 Workplace Relations Act (WRA). Although enterprises were the historic location for limited over-award bargaining, these acts progressively decentralized and concentrated industrial relations at the workplace. In 1990 awards covered 80% of the workforce with 67% reliant on awards for their terms and condi- tions (FWA 2010: 59). By 2008 only 17% were reliant on awards. Beyond this, the Acts allowed individual contracts and nonunion collective agree- ments; outlawed the closed shop, which had covered 54% of Australian workers in 1990 (de Turberville 2007); and did not provide any mechanism for union recognition or good faith bargaining. Strikes and lockouts were legalized, though secondary action and the ability to engage in pattern bar- gaining were severely restricted under the 1996 WRA. The impact of the Award system and the public ordering declined, though 2,300 federal and 1,700 state awards (Gray 2005) continued to establish the floor to collective and individual bargaining at the enterprise level. One aspect of this change was an increasing federalization of Australian labor law. In contrast to the earlier system in which state-level laws and awards played a more important role, the federal government asserted its authority to regulate labor relations matters under its corporations power in the Australian constitution (Lansbury and Wailes 2011). After the initial period of more gradual change, in 2005 Australian legislation shifted This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1057 dramatically to an extreme private ordering of employment relations with the Work Choices Act (Mccallum 2007). This shift effectively ended the ar- bitration system and the role of awards. It also provided unions no right to recognition, minimal access to the workplace, and promoted nonunion agreements while allowing employers to offer individual agreements on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Remarkably, Work Choices amended Section 421 of the Workplace Relations Act (WRA) 1996 to prohibit the use of pattern bar- gaining, with the objective of requiring bargaining and agreements to re- flect the "individual circumstances" of each business. Furthermore, in contrast to the distinction between mandatory and permissive subjects in the United States or absence of restrictions in Britain or Ireland, bargaining over issues that were not deemed to be "matters pertaining" to the employ- ment relationship had already been prohibited by Section 869 of the WRA 1996. Such issues included union involvement in the workplace, additional unfair dismissal protections (which were removed from workers in compa- nies with fewer than 100 employees), and the hiring of agency or contract workers. As an extreme imposition of a private ordering model, this Act was designed to weaken unions and to ensure that any bargaining would reflect the circumstances of the individual enterprise. Unions would be obliged to respond to the enterprise-specific proposals of the employer, creating maxi- mum flexibility. While minimum wage legislation replaced the Award sys- tem, the legislation imposed significant constraints on the ability of unions to strike while allowing offensive lockouts (Briggs 2007). With the defeat of the Howard government in the 2007 federal elections, in which industrial relations reform was a major issue, Australian industrial relations policy underwent another shift. In 2009, the Rudd-led Labour Party government passed the new Fair Work Act, which reversed some, though not all, of the changes that had been enacted under the previous Work Choices Act. Most notably, it abolished statutory individual contracts and returned the focus to collective bargaining as the primary mechanism for establishing terms and conditions of employment (Lansbury 2009). Nev- ertheless, it explicitly retained strong emphasis on private enterprise-level bargaining as exemplified by the continuation of the remarkable symbolic prohibition against pattern bargaining, restrictions on secondary boycotts, and the confinement of bargaining to matters pertaining to the employ- ment relationship (continuing to exclude, for example, constraints on man- agerial prerogative to hire agency or contract workers). The legislation includes a mixture of expanded rights for unions and some continued limitations: Employees have the right to be represented in collective negotiations and a "majority support determination" can be granted by Fair Work Australia on the basis of a simple petition, while good- faith bargaining was established (except in cases of multi-employer bargain- ing in which industrial action is also not permitted).' No distinction was `An exception relates to the low-wage bargaining stream, in which facilitated multi-employer bargaining can be established when no history of collective negotiations exists, inspired by the example of a similar system in the Canadian province of Quebec (Vranken 2010). This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org terms1058 II.RREVIEW made, however, between union and nonunion agreements: All agreements are made between the employer and employees (rather than with the bar- gaining representative), and employees are free to select their bargaining representatives or to bargain directly provided they are independent of the employer. That is, no exclusive representation rights are in effect, and mul- tiple bargaining agents are permitted, though agreements apply to all in the bargaining unit.' The private ordering is evident in that voluntary unionism extends into an individualistic model of collective bargaining in which the union is not regarded as representing the collective interests of employees. Union density has remained low, having fallen from 50% in 1982 to 18.4% in 2011.5 Overall, the Fair Work Act strengthens the position of unions, including union representatives having rights of access to workplaces even where they do not have existing members, while retaining strong constraints against industrial action. The most significant reintroduction of a public ordering occurred with the 22 Modern Awards, which establish general employment standards and minimum terms and conditions. These have extensive appli- cation, such that all collective agreements have to be judged "better off overall" by Fair Work Australia, the regulator (O'Neill, Goodwin, and Neilsen 2008). Comparison of Changes in Collective Representation The changes in labor law systems that we have described for the six coun- tries in this study are summarized in Table 1. The pattern of labor law changes has led to a decline in the public ordering of industrial relations and a con- vergence in the realm of collective labor rights, albeit with differences across the countries remaining. Union recognition rights are now the norm, though with operational differences. While Canadian labor law facilitates organizing through card check and snap elections, the slow process and ag- gressive employer campaigning in the United States inhibits the ability of the unions to gain bargaining rights. The British system represents a hybrid with a statutory recognition procedure serving as a legal backstop to a sys- tem designed to operate predominantly through voluntary recognition (Dukes 2008). Meanwhile both Australian and New Zealand labor law now feature comparatively easy acquisition of recognition and representation, as well as duties to bargaining in good faith, though without exclusive union bargaining. The dramatic change under the Work Choices Act to curtail rec- ognition or good faith bargaining rights in Australia was extreme, though was ultimately not sustained following the change in government and enactment "For example, in Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Union y Bansley Ply Lid (FWA 797) 2011. there were 25 bargaining representatives, including 3 unions and 20 employees, either appointed or self- nominated. Australian Bureau of Statistics 1962, Trade Union Members, Australia Cat No. 6525.0, Canberra: 2011 Employer Earnings, Bearfits and Trade Union Membership Cat No. 6310.0. This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor. org termsTable 1. Labor Law Systems by Country Labor lan (Inclusive or allowing Nonunion collective Union twooration Level of bargaining individual variation Country 1980 1980 2010 1980 United States Wagnerite Legal certifi- Legal certifica Enterprise fo Enterprise fo Inclusive Inclusive No No cation tion cused cusex Canada Wagnerite Legal certifi- Legal cerulica- Enterprise fo- Enterprise for Inclusive Inclusive Cation tion cused cused United King- Voluntarist Voluntary Legal certifica Unconstrained: Enterprise for Individual vari- Individual vari- Yes, and non- Yes, and non- dom tion underpins mixed multi cused ation permit ation permit independent independent voluntary pro- and single em ted bed union UnMNIS 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org terms This content downloaded from CESS player Ireland Voluntarist Voluntary Voluntary Unconstrained: Mixed, though Individual vari- Individual vari- Yes, and non- Yes, and non- mixed muli strongly cen- ation permit- ation permit- independent independent and single em- tralized ted ted unions unkowns ployer Australia Award System Award based Legal certificat Central awards Enterprise fo Inclusive Constrained No Yes tion (federal/state cused, no pat- individual with enterprise tern bargain- variation over-award bar- ing permitted permitted New Zealand Award System Award based Right to bargain Central awards Enterprise fo Inclusive Individual vari- No No and agree- cused, multi- ation permit- ments, with en- employer bar- bed terprise over- gaining award bargains possible continuedTable I. Continued Good faith Pre- or post-entry bargaining Status of strikes Striker replacement whion Shop Country 1980 2010 2010 2010 2010 United States Yes Yes Regulated to enterprise and Regulated to enterprise and Permanent Permanent Varies by Varies by contract negotiations, no contract negotiations, no state state ballots required ballots required Canada Yes Yes Regulated to enterprise and Regulated to enterprise and Temporary or period of pro- Temporary or period of pro- Yes Yes contract negotiations, no contract negotiations, bal- fection in most provinces; fection in most provinces; ballots required lots required no in Quebec no in Quebec and British Columbia 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC United King- No No Unregulated; beyond enter Regulated to enterprise, bal- Temporary and strikers can No. period of striker protecyes NO All use subject to https //about.jstor.org terms This content downloaded from dom prise permitted, no ballots lots required, no time pe- be dismissed (though not tixxn rided restrictions selectively) Ireland No No Unregulated; beyond enter- Regulated to enterprise, bal- Temporary and strikers can Temporary and strikers can No No prise permitted, no ballots lots required, no time pe- be dismissed (though not be dismissed (though not rind restrictions selectively) selectively) Australia No Yes Strongly discouraged; legal Regulated to enterprise and Award system and union Temporary Yes No and common law sanctions contract negotiations, bal- shop protection possible lou required New Zealand No Yes Strongly discouraged; legal Regulated, enterprise ballot Award system and union No Yes No and common law sanctions required, confined to con- shop protection possible tract negotiations, though multi-employer strike per mitted (if each enterprise ballot supports)CONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1061 of the Fair Work Act of 2009. This was similarly true in New Zealand with the replacement of the highly individualistic 1991 Employment Contracts Act with the more union-friendly 2000 Employment Relations Act. Ireland stands apart in not having recognition rights or a duty to bargain. The preservation of the Voluntarist model in Ireland has occurred in spite of continuing de- clines in union membership and the national partnership agreements. While the United States prohibits nonunion collective representation through 8(a) (2) of the NLRA, this representation is allowed in other coun- tries. In Canada, nonunion collective representation is allowed by the ab- sence of an equivalent to the 8(a) (2) ban in Canadian versions of the Wagner Act model. In Australia, the Fair Work Act of 2009 draws no distinc tion between union and nonunion collective agreements, although as in New Zealand, bargaining representatives have to be independent of the em- ployer, which is not the case in either Britain or Ireland. Each of Britain, Ireland, Australia and, most starkly, New Zealand allow individual contracts to diverge from any collective agreement. New Zealand has, however, estab- lished the strongest good faith provisions, which are absent in only Britain and Ireland Britain and Ireland have retained a basic structure of immunities as op- posed to a right to strike. By contrast, the introduction of a system of rights to strike in aid of collective bargaining in Australia and New Zealand (which had historically been contrary to the Arbitration and Award system in the- ory, if not in practice) has meant a formal convergence with the North American model that has always contained this explicit legal support for the right to strike in support of bargaining. Some differences remain in this area as well. In Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, author rization for strikes requires ballots of differing degrees of complexity whereas such requirements are absent in the United States. Permanent re- placement of strikers is permitted in the United States, while this is true in most of Canada only for temporary replacements. In Britain, from 2004 on- ward, workers on strike have received protection from dismissal for 12 weeks. New Zealand has strong restrictions even on internal worker reas- signment, though such protections are absent in Ireland. Overall though, in the recognition and regulation of strikes as the primary economic weapon of unions in support of collective bargaining, we see a general trend of con- vergence across the Anglo-American countries, paralleling the convergence in other areas of labor law and collective representation. Individual Employment Rights As in the area of collective labor representation, when we look at individual employment rights regimes we see a substantial shift in the structure of reg- ulation in some of the countries examined, but less so in others. Our com- parison here focuses on three basic areas of individual employment rights: minimum wage and hours laws, general benefits and leave entitlements, and unfair dismissal. These three areas of employment rights have been This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org terms1062 ILRREVIEW used previously among comparisons of employment and labor standards (e-g., Block and Roberts 2000). We focus on them in particular because they capture important aspects of legal regulation of the employment contract and relationship, as opposed to more general social welfare systems that may or may not be tied to the particular employment relationship (e.g., health or unemployment insurance). Minimum Wage and Hours Laws Minimum wage and hours laws have been a basic component of employ- ment standards regulation in the North American countries since the mid- 20th century. In the United States, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a national minimum wage and entitlements to overtime pay (time-and-a-half of regular pay) for work in excess of 40 hours a week. This policy has remained a stable part of U.S. employment standards law since that time. The Canadian provinces enacted similar minimum wage and overtime pay regimes relatively soon after the United States, which have again remained the policy though with some expansion to include addi- tional minimum terms of employment such as vacation leave entitlements. Employment law in the United Kingdom and Ireland was historically shared prior to Irish independence and lacked provisions for a generalized minimum wage, though they had a long tradition of measures that acted as a component of state support for collective bargaining as part of a public ordering framework. These included the 1891 Fair Wage Resolution to ensure government contracts did not undermine terms and conditions in industry collective bargaining and the 1909 Trade Boards Act, which estab- lished minimum pay on an industry-wide basis for unorganized workers. In the United Kingdom, the 1945 Wages Councils Act enabled terms and con- ditions to be set above a basic floor. Together with Schedule 11 of the Em- ployment Protection Act they allowed for a going-rate, often determined by collective agreements, to be extended to unorganized workers. Historically these covered 10 to 15% of the workforce (Katz and Darbishire 2000: 75; Deakin and Green 2009), though the Thatcher governments progressively abolished them by 1993. Under the Labour government of Tony Blair, how- ever, the United Kingdom introduced the general National Minimum Wage Act in 1998, establishing a common minimum consistent with a private or- dering model. The counterparts to Wages Councils in Ireland were the Joint Labour Committees (JLC). Enacted under the 1946 Industrial Relations Act, these have continued to provide protection to pay and core working conditions for vulnerable workers in certain low-paid sectors, such as agriculture, retail, and hotels. The Irish social partnership system has enabled them to survive along with limited Registered Employment Agreements (REA), which can extend "representative" collective agreements to cover sectors, such as con- struction. In 2010 this had rates as high as the equivalent of US$20.55 for experienced electrical contractors. Together, the JLCs and REAs protect some 15% of the private sector workforce (Duffy and Walsh 2011). Ireland This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1063 complemented these historic, but limited scope, JLCs and REAs by intro- ducing its first national minimum wage law in 2000, which drew upon the United Kingdom's model (Teague 2006).6 In Australia and New Zealand, the centralized Award systems went fur- ther than the employment standards laws in other countries by establishing generally applicable terms and conditions of employment through awards, including standard pay levels on an industry or occupational basis, at a level that resulted in a wage-based welfare state. While a federal minimum wage in Australia was implemented in 1966 (Stokes 1973), it was the higher fed- eral and state Awards that underpinned wages. With the abolition of the Award system a general minimum wage law was introduced under Work Choices, drawing on the U.K. model. The Fair Work Act partially reversed this trend through the restoration of 10 national employment standards es tablishing minimum protections in areas such as hours of work, vacations, and redundancy pay. Furthermore, the legacy of the Award system has been restored with 122 Modern Awards that provide a second, higher, and more detailed safety net of regulations on work and employment conditions on an industry or occupational basis for those earning less than AUS$113,800 in July 2010 (approx. US$104,500 in 2010 exchange rates). While the mini- mum wage is high by international standards, reflecting the historic "fair- ness standard," it has low impact: Modern Awards provide significantly greater vertical coverage as well as providing protections to casual workers through 25% casual worker wage premiums. New Zealand was one of the earliest adopters of a minimum wage, with legislation dating from 1894 and the Minimum Wage Act from 1945 (Pa- checo 2007). The Awards system created a more granulated effect, however. Awards had a coverage of 67% in 1990 (Bray and Walsh 1998: 362) and ex- isted in a multi-tiered system of protections that included the minimum wage, occupational awards, general wage adjustments, collective agreements at the enterprise, and blanket coverage provisions. With the ECA in 1991 the minimum wage protections operated alone. The significant change in both Australia and New Zealand has been the shift in the mechanism for wage regulation away from the establishment of general wage levels and to- ward a system of minimum wages with most employment relationships typi- cally involving the establishment of higher wage levels, either through direct employer wage setting or through collective or individual negotiations. Therefore, some significant convergence in minimum wage provisions has transpired. As Table 2 shows, however, the comparative protection given by the minimum wage is what stands out. The rate varies from US$7.25 in the United States in 2011 to the equivalent of US$9.88 in Australia.' The dif- ference in protection as a percentage of median wages is substantial: In New "In July 2011 the procedure for issuing Employment Regulation Orders under the 1946 Industrial Relations Act was deemed unconstitutional by the High Court, requiring legislation to rectify this. "All minimum wage rates have been drawn from the U.K.'s National Minimum Wage: Laws Pay Commission Report 2012 (April), Table AS.1, p. 174, adjusted using OECD purchasing power parity rates from September 2011 to U.S. dollars. The data for Canada are a weighted average of provinces. This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsTable 2. Minimum Employment Standards by Country Minimic median Range Unfair Employment Country mage LIS Vacation/Holidays (annual) Sick leave (annual) Maternity four dismissed discrimination United States $7.25 None 12 weeks unpaid for serious ill- 12 weeks unpaid No ness only Canada $7.54 2-3 weeks plus 5-10 public holi- 10-12 days unpaid, longer for se- 50 weeks paid (unemployment in- Yes Yes 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org terms This content downloaded from days nous illness surance) United King $7.77 4 weeks plus & public holidays Up to 28 weeks paid at $79.15/ 39 weeks paid plus 13 weeks un- Yes Yes dom Week paid Ireland $8.77 4 weeks plus 8 public holidays Public social Insurance illness 26 weeks paid plus 16 weeks un- Yes benefit pay paid Australia $9.88 4 weeks plus 10 public holidays, 10 days paid 18 weeks paid plus 12 months un- Yes Yes plus long service leave paid New Zealand $8.07 59 4 weeks plus 11 public holidays 5 days paid 14 weeks paid plus 38 weeks un- Yes Yes paid Source UK's National Minimum Wage Low Pay Commission Report 2012 (April), Table AS.1 and Table A3.2 for median rates. Notes: Minimum wage rates are for 2011. They are adjusted to U.S. dollars using OECD purchasing power parity rates from September 2010. For Australia, median rates are calculated using the Labour Force Survey, For Canada most employment laws are set at the provincial level. For minimum wages a provincial weighted average is used. Otherwise, the standards listed are ranges for the provinces.CONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1065 Zealand this equates to 59% of median wages while Ireland and, in particu- lar, Australia retain multitiered mechanisms of wage support. The United States is the outlier, providing the lowest protection at just 38% of median wages. General Benefits and Leave Entitlements Most of the Anglo-American countries also provide basic entitlement to pa- rental leave (Table 2). Indeed, substantial similarities occur in the combina- tions of part paid leave, with government funding support, and part unpaid leave. The convergence is shown insofar as New Zealand introduced job protection for those entitled to parental leave in 1987 and paid leave in 2002, while in Australia the more limited policy of only unpaid leave evolved first by the addition of a universal AUS$5,000 "baby bonus" in 2004, and in 2010, 18 weeks of paid parental leave. While Canada has the longest paid leave, the United States stands out for having by far the most limited bene- fit. It provides only 12 weeks unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act, which is further limited to larger employers and as a result covers less than half (around 46%) of the private sector workforce (Waldfogel 1999). A similar pattern holds in the area of minimum standards for vacation or holiday leave. Most of the Anglo-American countries have generally similar minimum vacation and public holiday entitlements enacted in employment law (Table 2). In the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia, employees are entitled to 4 weeks of vacation and between 8 and 11 public holidays. Australia also provides for additional extended periods of long ser- vice leave (after 7 to 15 years employment with the same employer) under various state or federal awards. In Canada, the amount of leave entitlement varies by province, though with 8 to 10 public holidays and 2 weeks of vaca- tion being a common minimum entitlement." The major exception is again the United States, where no minimum vacation entitlement or paid public holidays are specified in employment law. Unfair Dismissal In the area of unfair dismissal, we find across most of the Anglo-American countries the establishment of basic substantive and procedural protections against wrongful termination of employment. In the United Kingdom, em- ployees have had legal protections against unfair dismissal since 1971, en- forceable through the Employment Tribunals system, while in Ireland these were introduced in 1977. In Australia, general protections against unfair dismissal emerged first in the states from 1972 and were then included in federal Awards from 1982, before having general effect through legislation in 1993 (Chapman 2003). One of the major features of the 2005 Work "Leave in some provinces rises with years of service, for example, 2 weeks initially and then 3 weeks after 5 years of service in British Columbia and Alberta. This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org terms10-48 ILKREVIEW this period. Do we see a common trajectory of change and, if so, what are the characteristics and nature of this change, and why has it occurred? The question of how labor and employment law systems have changed in recent decades in the Anglo-American countries is important as a practical matter for understanding the state of employment relations in these coun- tries. Such changes are also important elements in analyzing the broader comparative political economy of labor. Historically, comparative research has been concerned with the question of whether over time there will be a convergence of national industrial relations systems. In their pioneering comparative study, Industrialism and Industrial Man, Clark Kerr, John Dun- lop, Frederick Harbison, and Charles Myers (1960) argued that national industrial relations systems worldwide were converging on something akin to an American-style model of collective bargaining due to the necessities of managing modern industrial factories, a proposition supported in an early empirical study by Stephen Kobrin (1977). By contrast, Harry Katz and Owen Darbishire (2000) argued that there was a converging divergence in which a range of different countries were seeing a similar phenomenon of growth in organizational-level variation in patterns of work and employment practices. At the same time, the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) literature in compara- tive political economy emerged as a leading theoretical perspective for com- parative analysis of the roles of labor and regulatory systems, arguing that there is a form of dual convergence on two different models (Hall and Sos- kice 2001). The VoC framework of Hall and Soskice (2001) distinguished between two paradigmatic capitalist types: the coordinated market economics (CMEs), exemplified by Germany but also including other continental European countries and Japan, and liberal market economics (LMEs), exemplified by the United States and the other Anglo-American countries. Each of these models is characterized by a particular set of relationships among the sys- tems of corporate governance, inter-firm relationships, worker skill develop- ment, and labor markets. The LME model is based on outsider governance and financing of corporations, market relations between firms, and, on the labor side, general rather than firm-specific skills, and competitive labor markets with relatively weak regulation. The dichotomous nature of the VoC analysis has been subjected to im- portant critiques, not least of which relating to the diversity of capitalist forms that exist (Amable 2003; Crouch 2005). Nevertheless, while Bruno Amable argued that greater heterogeneity exists, presenting five models of capitalism, the Anglo-American countries remain identified as a "highly ho- mogenous cluster" (2003: 20), with the exception of Ireland which is cate- gorized as a continental European form. The VoC framework presents a powerful conceptual model and, for Peter Hall and David Soskice (2001) in particular, an internal systemic logic to the nature of labor regulations can be found in the LME model, in which the flexibility and competitive labor markets reinforce a system of impatient capital seeking short-term rewards. Amable (2003) made the important distinction, however, between institutional This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor. org/terms1066 ILRREVIEW Choices legislation was the removal of unfair dismissal protections in firms of fewer than 100 employees, excluding 56% of the workforce, though these were restored by the Fair Work Act (FWAEM 2008). In each of these coun- tries the protections extend to rights of compensation in cases of redun- dancy, and the protection of terms and conditions in cases of the transfer of businesses or contracting out of services. New Zealand provided protection against unfair dismissal from 1973, though only for union members, thus covering 60% of the workforce (Anderson 1997). This provision was ex- tended as a basic individual employment right in the 1991 ECA, though no rights to redundancy compensation are available, and only vulnerable work- ers have protection in the case of business transfers, which was introduced in 2004 (Walker 2007). North America presents a contrast in this area. Canadian employment law provides for protection against unfair dismissal through a combination of employment standards legislation and common law rights against wrong- ful dismissal. Rather than reinstatement, however, the standard remedy for unfair dismissal in Canadian employment law (as in our other countries) is damages equivalent to lost salary or wages for a period equal to what the employer should have provided in reasonable notice before dismissal (Col- vin 2006). This can be a substantial amount, as much as one month per year of service under common law rights. In the area of unfair dismissal, the United States is again the outlier. The general employment law in the United States continues to be employment-at-will, under which an employer may dismiss an employee for "good reason, bad reason, or no reason at all." without any requirement of notice or severance pay. The most important exception to this rule is that U.S. law does prohibit discrimination in cm- ployment (in such areas as gender, race, age, and disability). Employment discrimination claims can be pursued through the general court system, commonly involving jury trials with the potential for much larger damage awards than found in other countries. Given concerns over major damage awards if an employment decision is found to be tinged by discriminatory motives, American employers tend to exercise a degree of caution in dis- missal decision making that does not reflect the seemingly high degree of flexibility inherent in the employment-at-will rule (Colvin 2006). Comparison of Individual Employment Rights What is striking in this comparison of employment laws and standards sum- marized in Table 2 is the relative similarity in the minimum standards to which individual employees in most of these countries are entitled. Whereas Canada, the United States, and New Zealand had general minimum wage laws before the 1980s, now all countries have adopted them with levels rang- ing from US$7.25 to $9.88. Most countries provide for a minimum paid an- nual vacation entitlement of around 2 to 4 weeks, plus 8 to 11 days off for public holidays. Maternity and parental leaves are generally around one year with some portion of this paid. All countries provide for legal protection This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1067 against discrimination in employment. Almost all countries provide unfair dismissal protection, with employees entitled to compensation if dismissed without notice or cause. In general, an employee could move between two of these countries to take up a new job and expect that the minimum level of employment standards to which he or she would be entitled would be relatively similar. The major outlier in this area is the United States. Some areas of U.S. employment law do parallel that of the other Anglo-American countries. With regards to employment discrimination, the United States was a leader with the other Anglo-American countries adopting laws paralleling Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent American discrimination laws (Mccallum 2007). Employees in the United States have minimum wage protections as in the other countries, albeit at a lower level equivalent to just 38% of the median wage with low levels of enforcement. More significant divergence exists in the continued adherence to the employment-at-will rule in the United States, denying any protection against unfair dismissal or any entitlement to reasonable notice or compensation for dismissal. A fur- ther substantial divergence is the lack of entitlement to either annual vaca- tion leave or paid sick leave. Finally, U.S. employment law standards are much more limited than in other Anglo-American countries in maternity or parental leave: only a limited segment of American private sector workers are entitled to just 12 weeks of unpaid leave. Convergence on a New Anglo-American Model If we had conducted a similar comparison of the six countries examined in this study in 1980 at the outset of the Thatcher/ Reagan era, the analysis would have emphasized the significant variation that existed, with the Anglo- American countries divided into three pairings: the Wagner Act industrial relations systems of the United States and Canada; the Voluntarist system of collective bargaining and strong unions in the United Kingdom and Ire- land; and the highly centralized, legalistic Award systems of Australia and New Zealand. Indeed, such a historical perspective contradicts the idea that there has been a long-standing Anglo-American model of liberal market economic ordering as has sometimes been suggested, such as in the variet- ies of capitalism literature (Hall and Soskice 2001). Looking at the current state of the labor and employment law systems in these six countries, how- ever, we argue that there has been growing convergence in two major areas. Convergence has occurred in the area of labor rights toward private or- dering of employment relations and away from the idea of work and em- ployment being a matter subject to public ordering. By private ordering, we mean the idea that work and employment terms and conditions are primar ily determined at the level of the individual organization, whether through collective bargaining between unions and employers at the organizational level, through individual negotiations, or through unilateral employer es- tablishment of the terms and conditions of employment. The shift away from This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org/terms1068 ILRREVIEW public ordering of work and employment is most dramatic in the cases of Australia and New Zealand, where the publicly established system of central- ized awards has given way to organizational-level ordering of employment relations through workplace or individual agreements. In the United King dom, the shift to greater private ordering is most evident in the breakdown of multi-employer collective bargaining and industry-wide standards en- forced by strong unions, together with the growth of employer determina- tion of conditions at the enterprise level. By contrast, the much lesser degree of structural change in the labor rights area in North America reflects the historical situation that the Wagner Act model was from the outset a model built around the idea of private ordering. The legal regulation of primarily enterprise-level union organizing and collective bargaining is premised on the idea that the individual organization is the appropriate level for deter- mination of work and employment conditions. The areas where we have seen change in North America, such as the breakdown of multi-employer and pattern bargaining, reflect a deterioration of a superstructure of partial public ordering built on top of the basic Wagner Act model during the 1950s through the 1970s and the decline in unionization rates. Turning to the area of employment rights, we also see a convergence across the six Anglo-American countries toward a model in which the role of employment law is to establish a basket of minimum standards that are built into the employment relationship, which can then be improved upon by the parties. Again, the shift has been particularly dramatic in the cases of Australia and New Zealand, with the previous Award model involving the establishment of relatively generous general terms and conditions of em- ployment being replaced, in part, by employment laws that establish a more basic set of minimum standards. Although additional wages or benefits could always be provided above the award levels under the old system, now the minimum standards are a more limited set of basic protections rather than a broader foundation to build upon as in the past. In the United Kingdom and Ireland by contrast, the shift has been toward a greater formalization of minimum standards of employment through expanded employment laws, in contrast to the earlier system of voluntarism. Again change in this area has been less significant in North America because the system of employ- ment regulation was historically based on the concept of employment law as establishing a minimum basket of employment standards, through the Fair Labor Standards Act in the United States and its Canadian counterparts. Within these general trends, we do see some variation in the degree of convergence on these models of labor and employment rights regulation across the Anglo-American countries. The strongest degree of similarity in adoption of the private ordering in labor rights and the minimum standards basket in employment rights is found in four of the countries; Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and, following the replacement of the 2005 Work Choices Act with the 2009 Fair Work Act, Australia. Each of these coun- tries has adopted labor laws that favor organizational-level economic order- ing, but with reasonably substantial protections of trade union organizing This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1069 and bargaining rights, and a set of minimum employment standards that include minimum wage, basic leave entitlements, and unfair dismissal pro- tections. One interesting indicator of the degree of convergence across these four countries is the relative similarity between them in union repre- sentation levels. Whereas in 1980 union representation varied between 30 to 35% in Canada and over 50% in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, current overall union representation levels in all four countries are around 20 to 30%, with private sector density ranging from 9% in New Zealand to 18% in Canada. The first outlier is Ireland for two reasons. First, the voluntarist nature of the system, without union recognition rights, has continued, though the public policy suasion for union recognition has declined and industrial ac- tion has been confined to the enterprise level. Second, Ireland has contin- ued to have a significant degree of public ordering of employment relations through the national partnership agreements. Partnership promoted the remarkable success of the Irish economy from 1987 to 2008 and, in turn, was sustained by it. Even during this period, however, it was significant that the system of truncated partnership combined central coordination of wage increases with significant leeway for the private ordering of employment re- lations at the enterprise level. Within that realm, the minimum employment standards play a similar role to those in our other countries, and it is note- worthy that while public sector union density is approximately 80%, that in the private sector is not dissimilar to our other countries at 20%. The ques- tion for the future is what will be the extent of the impact of the current deep economic downturn. This downturn brought the formal centralized partnership system to a close at the end of 2009, though informal coordina tion has continued. Nevertheless, when combined with signs of increasing employer aggression to unions, certainly the potential exists for the system to evolve further toward enterprise-level private ordering The other outlier is the United States. Structurally its system is similar to the other Anglo-American countries in emphasizing private ordering in labor law and the role of employment law as being to establish a minimum set of basic standards. This U.S. system, however, has involved a general fa- voring of the interests of employers over those of employees and organized labor. In the area of labor law, this favoritism is reflected in the relatively weak enforcement of the right to organize and the ability of employers to hire permanent replacement workers. In the area of employment law, the emphasis on employer interests can be seen in the continued use of the employment-at-will rule barring most actions for unfair dismissal and in the limited extent of minimum employment standards, such as the lack of paid sick leave or vacation entitlements and low minimum wage. Factors Influencing Convergence A definitive answer to the question of why there has been a convergence across the Anglo-American countries is beyond the scope of this paper, This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org terms1070 ILKREVIEW although we suggest some possible explanations. Note that any explanat tion must be able to account for both the divergence of systems across these countries before 1980 and the subsequent convergence on the new Anglo- American model. One natural explanation is the shared political and cultural histories of these six countries that were at one time part of the British Empire. The common linguistic and cultural ties may have facilitated the sharing of ideas in the economic and social policy realm, leading to convergence in prac- tices. More specifically, all six countries retain the common law heritage as the basis for their legal systems, which may in turn encourage convergence. The main limitation of this explanation is that it does not account for the divergence before the 1980s when the heritage was as strong and yet three strikingly different employment relations systems existed. This limitation suggests that while cultural and linguistic ties may have facilitated transmis- sion of common economic and social policy ideas in recent decades, such ties are not as likely to have operated on their own as the driver of change. Another possible explanation for convergence is a high degree of inte- gration of the economies within the three pairings in question. Canada and the United States are the world's largest trading partnership, and their closely integrated economies became even more deeply intertwined with the 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and subsequent 1993 North American Free Trade Agreement. Similarly, the United Kingdom and Ire- land have long had closely integrated economies, which are now linked through their joint membership in the European Union (EU). Australia and New Zealand are similarly linked by the 1983 Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement and also have historical eco- nomic similarities as export-oriented agricultural economies. These factors do a good job of explaining the strong parallels within the pairings that ex- isted in the era before the 1980s, although they do less well in accounting for the more recent convergence across the broader set of Anglo-American countries. Prior to the entry of the United Kingdom into the EU in 1973 (at the time known as the European Economic Community [EEC]), Britain served as a major export market for both Australia and New Zealand. Since that time the proportion of Australasian exports going to Britain has steadily declined. The primary trading partners for Australia and New Zealand are now East Asian countries, not other Anglo-American countries. This sug- gests that economic integration is not likely to be the driver of convergence. Pressures from globalization of product markets may explain some of the convergence. Certainly in the vigorous political debates over reform of the employment relations systems in Australia and New Zealand, the need to enhance competitiveness in an era of globalization has been a powerful ar- gument for moving away from the traditional Award systems. Similarly in the United Kingdom, competitiveness arguments were some of the concerns raised with the earlier, strong trade union-centered Voluntarist system. Fur- thermore, the extent of product market competition experienced by enter prises has played a significant role in the decline of collective bargaining This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https //about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1071 (Brown et al. 2009). Even in the United States, which has seen less change in formal laws, the growth of international competition was one of the major factors leading to the shift in labor relations practice toward a more strongly anti-union approach by many employers (Kochan, Katz, and Mckersie 1994). Based on the prominence of these arguments in employment relations re- form debates across the Anglo-American countries, it would be hard to argue that globalization was not an important element in convergence. Furthermore, the expansion of minimum employment standards can be viewed as one governmental response to the decline of collective represen- tation in an era of heightened global product market competition. Is it in- evitable, however, that globalization should lead to the particular type of convergence on the new Anglo-American model? Interestingly, Ireland is one of our outliers even though it has an exceptionally internationally ori- ented economy. Indeed, its centralized social partnership system was in part an effort to establish an economic and policy environment that would en- hance its international competitiveness and encourage foreign investment (Teague and Donaghey 2004). This largely successful effort has been an important factor in the Irish economic boom since the 1980s. If the social partnership system is unable to survive recent economic turmoil and Ire- land begins to resemble the new Anglo-American model, an additional piece of evidence will have been gained in favor of the globalization and international competition explanation for convergence. A related explanation is that convergence is being driven not by global- ization per se but rather by the emergence of new systems of work organiza- tion and human resource practice that are important for competitiveness. In the period from the 1980s to the present, we have seen increasing argu- ments that organizations need to adopt new, more flexible forms of work organization to better harness the value of their workforces (Appelbaum and Batt 1994). From an industrial relations system perspective this has led to arguments about the need to decentralize the determination of em- ployment terms and conditions to the organizational level to allow for the flexibility needed under these systems (Katz 1993). When we look at organi- zational practices, evidence emerges of common trends toward the adop- tion of a range of different patterns of work organization and human resource management across the countries we are examining (Katz and Darbishire 2000). As policymakers are faced with this common shift toward a set of or- ganizational practices designed to achieve competitiveness, they appear to be engaging in common policy responses of establishing labor and employ- ment law systems that facilitate the decentralized implementation of these practices. These arguments are consistent with the VoC perspective that institutional complementarities exist and that increasing product market competition has been a catalyst for labor law reform. Indeed, even though three models existed in 1980, these countries did share a presumption of managerial pre- rogative at the workplace, even if subject to a negotiated order. The growth of a private ordering model remains consistent with this presumption of This content downloaded from 144.120 142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org terms1072 ILRREVIEW managerial prerogative implying a possible path dependency even if not necessarily a functionalist one. One impact, certainly, has been to constrain the ability to generate enterprise-level partnerships: Concerted attempts, most particularly in Ireland and New Zealand, to build high-wage, high-skill relationships have come to little. Nevertheless, significant variation remains in the economic performance among our six countries that is not entirely consistent with the functionalist and systemic logic of the VoC model. Fur- thermore, we note that in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom a policy "overshooting" in the form of a more extreme model of deregu- lated labor markets existed, premised on rationalist economic arguments, before the current models were adopted. The similarity of policy responses across these countries also displays structural isomorphism (Amable 2005) as a result of the significant inter- change of economic and social ideas. Commonality in heritage and politi- cal institutions may have facilitated the spread of the specific set of labor and employment practices that these countries adopted in response to the pressures of globalization and the advent of new systems of work organiza- tion, while also legitimating political policy preferences. The institutional borrowing has a clear history, as the United Kingdom unsuccessfully at- tempted to restructure its industrial relations system along the Wagner Act model in 1971 (Gould 1972). Certainly the spread of neoliberal economic ideas in the Anglo-American world received a major boost from the politi- cal success of Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Reagan in the United States. The influences were both philosophical and empirical. In the United Kingdom the economic rationalist arguments of Friedrich Hayek were par- ticularly important (Wedderburn 1988), while in New Zealand Richard Epstein held sway (Dannin 1997). The moves toward deregulated labor markets in 1991 with the ECA in New Zealand arguably owed much to the perceived successes of the Reagan and Thatcher programs in the United States and the United Kingdom, while states in Australia such as Western Australia and Victoria drew heavily on the New Zealand experience, fur- ther influencing the Howard administration's goals leading up to the 2005 Work Choices Act. The retreats from the neoliberal extremes also illustrate the transmission of policy ideas among the Anglo-American countries. The statutory recogni- tion system in the United Kingdom borrows features of the North American Wagner Act model, particularly the more union-friendly Canadian variant, though adapted to fit the voluntarist industrial relations legacy. The experi- ence of New Zealand with the ERA showed significant policy learning with regards to Wagner Act good-faith bargaining provisions. Australia did like- wise with the Fair Work Act for recognition and good faith, while seeking to avoid the perceived legalism and employer hostility of the United States (Forsyth 2007). The significance of agency is also illustrated by the case of Ireland, where the principal political parties are not divided on ideological grounds and the partnership approach was adopted at a point of economic This content downloaded from 144.120.142.4 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 13:47:03 UTC All use subject to https /about.jstor.org termsCONVERGENCE IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS INSTITUTIONS 1073 crisis in 1987 with the deliberate attempt to avoid the neoliberal solution then being implemented in the United Kingdom. The success of this move ensured there was no c

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts