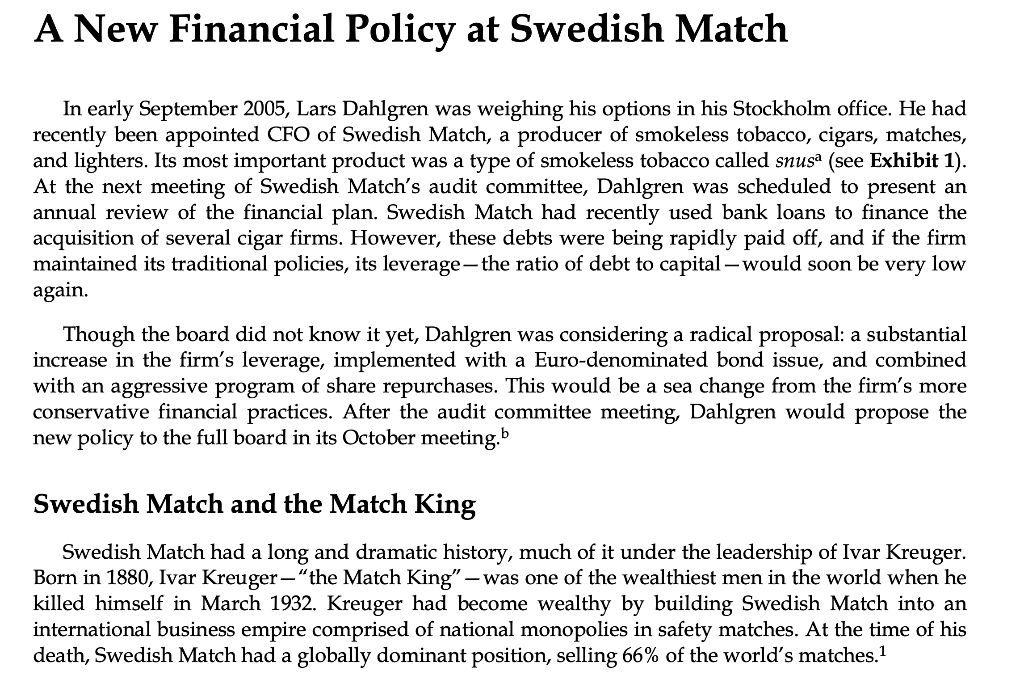

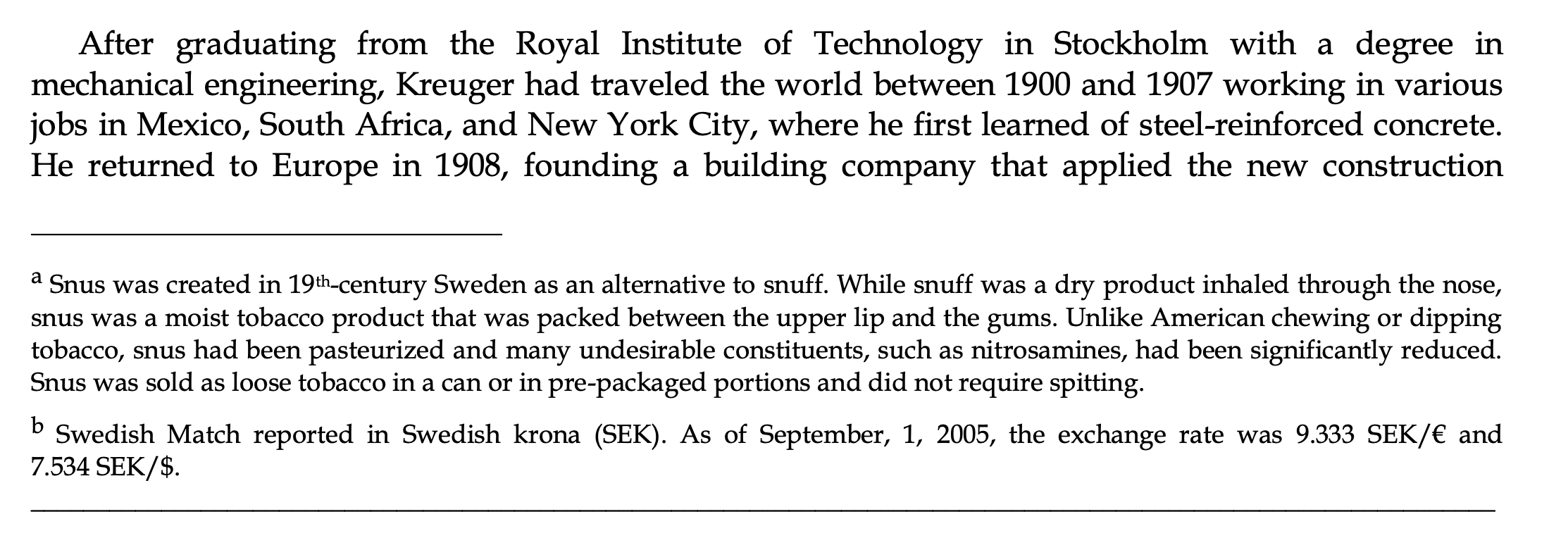

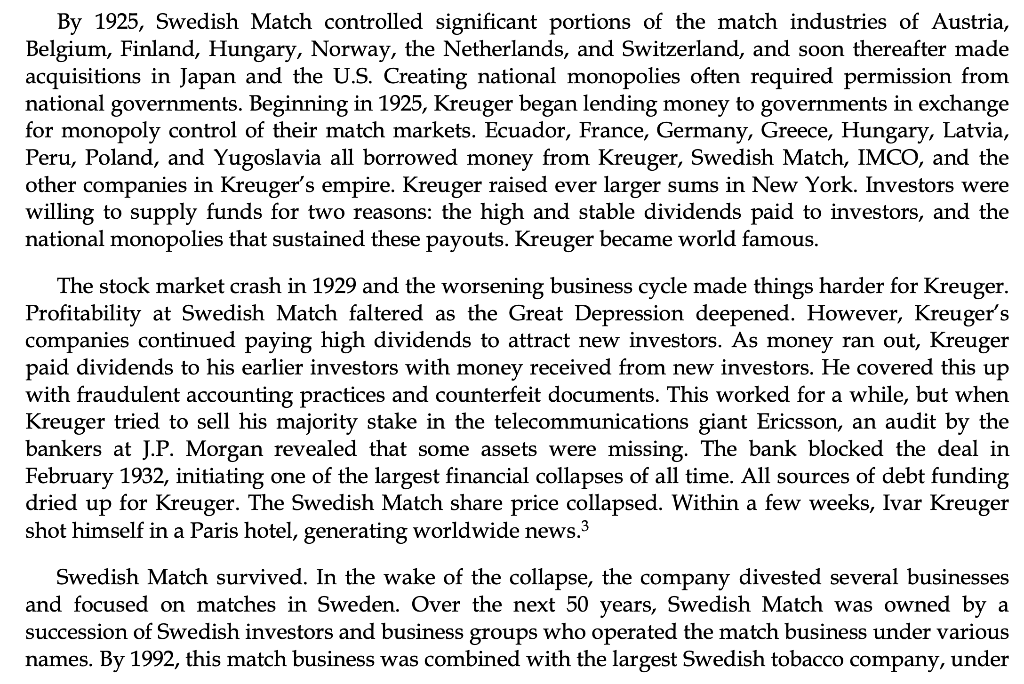

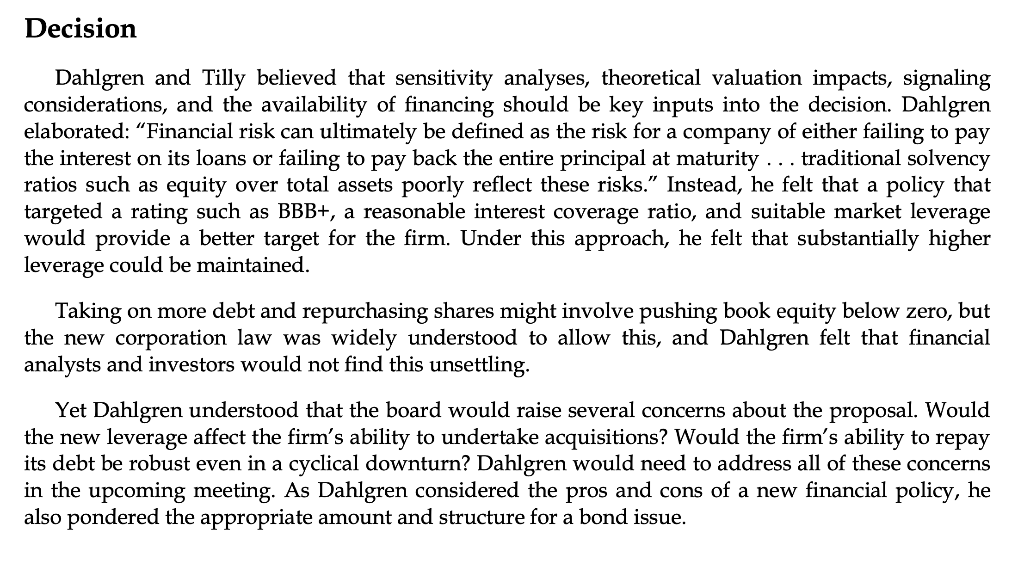

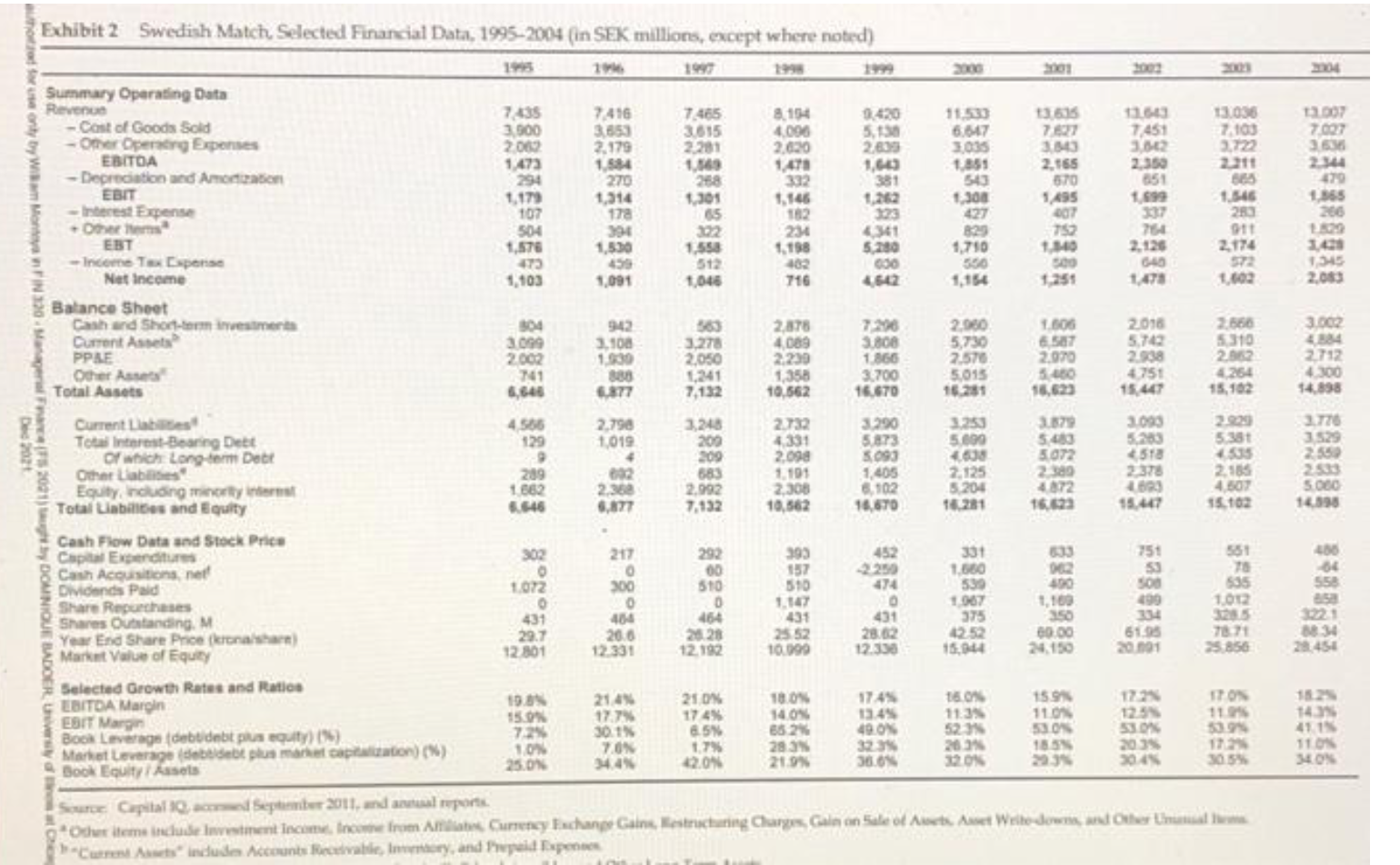

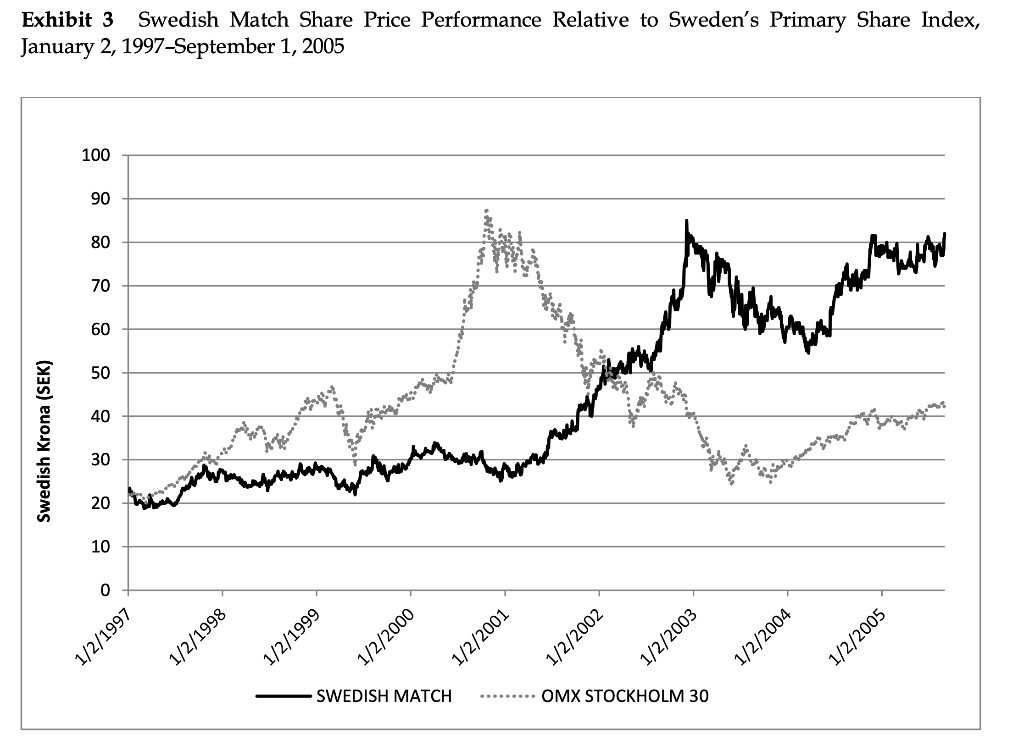

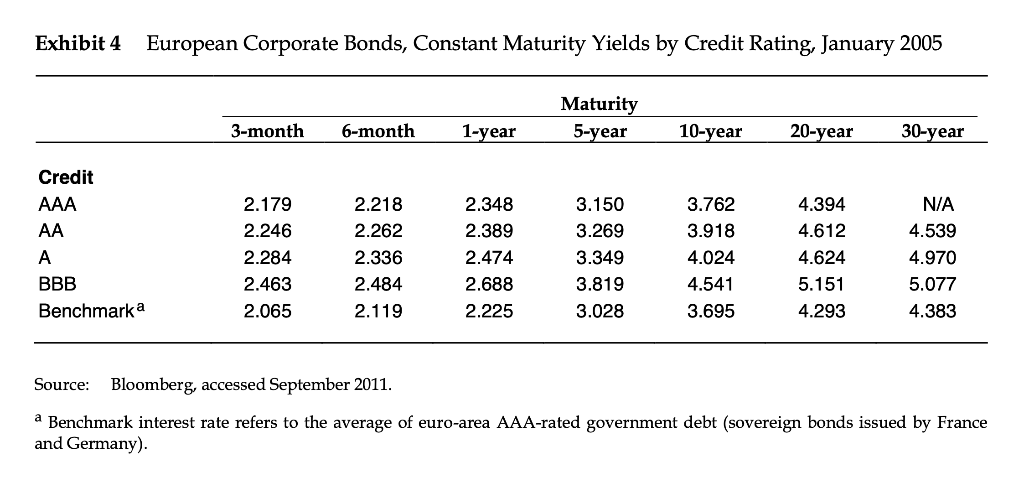

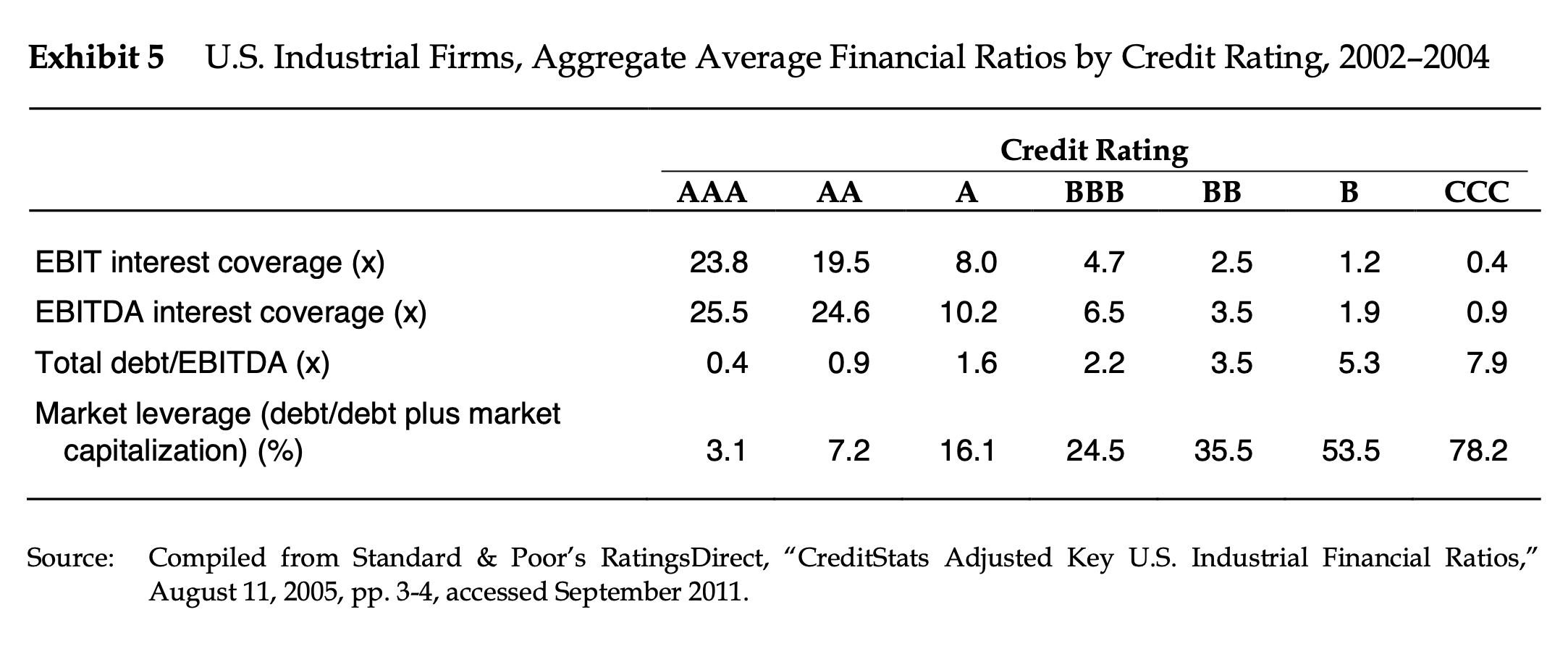

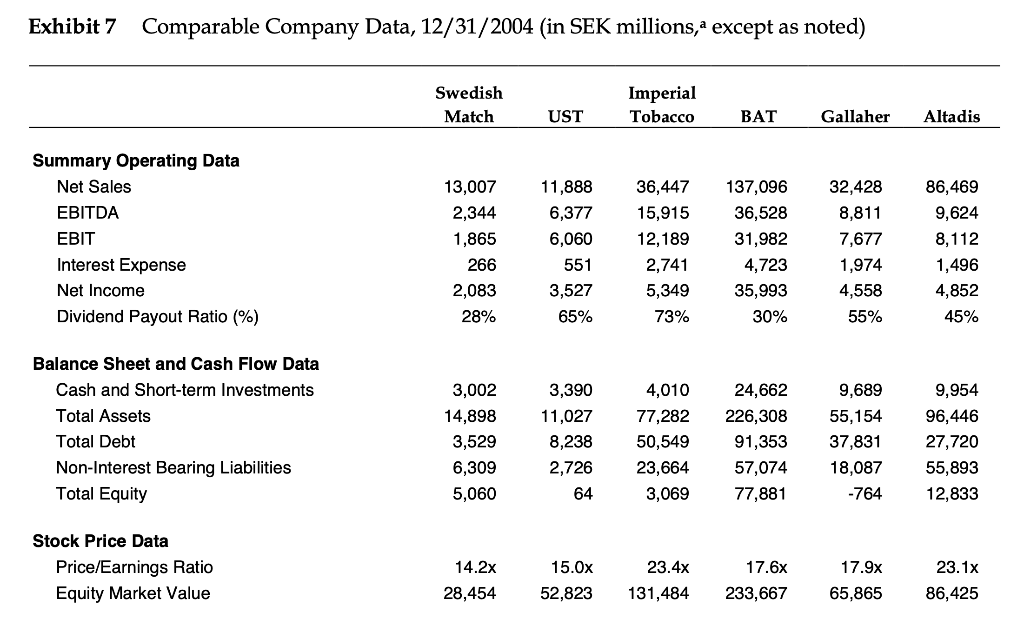

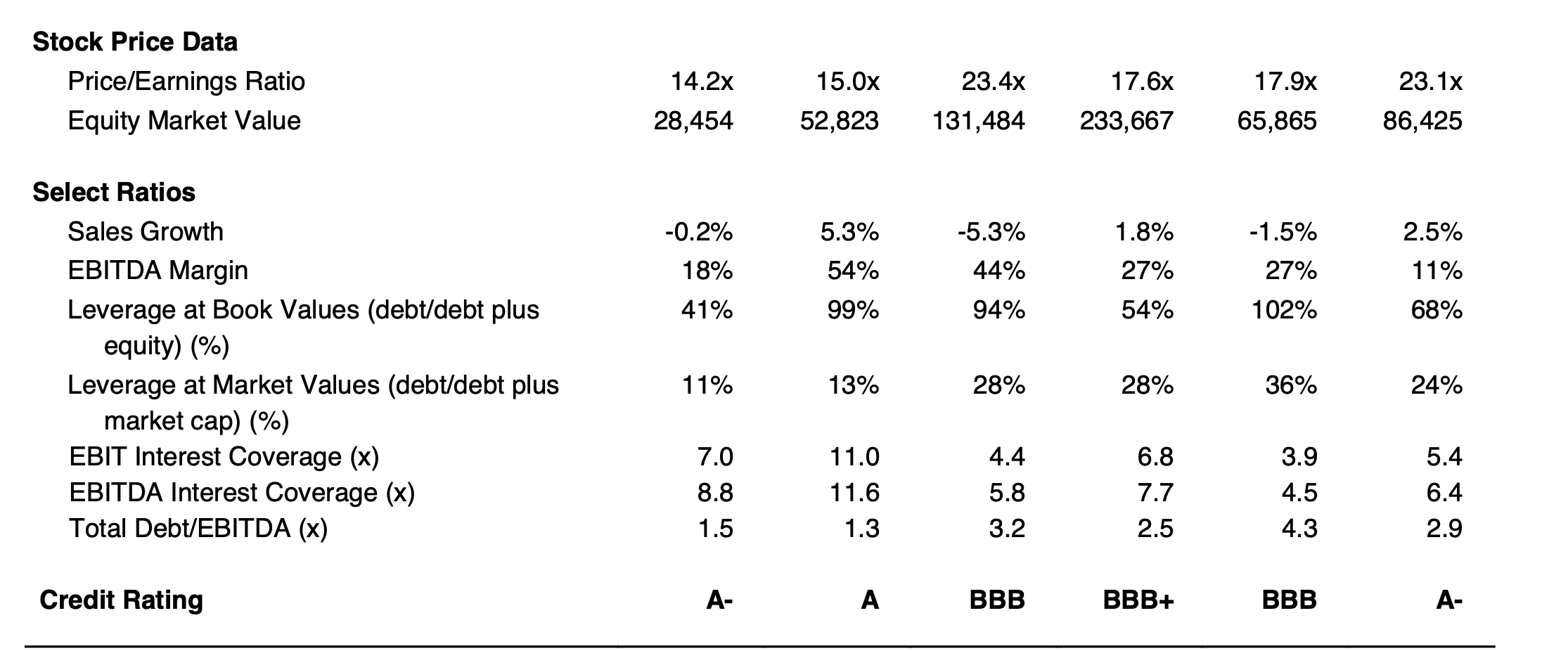

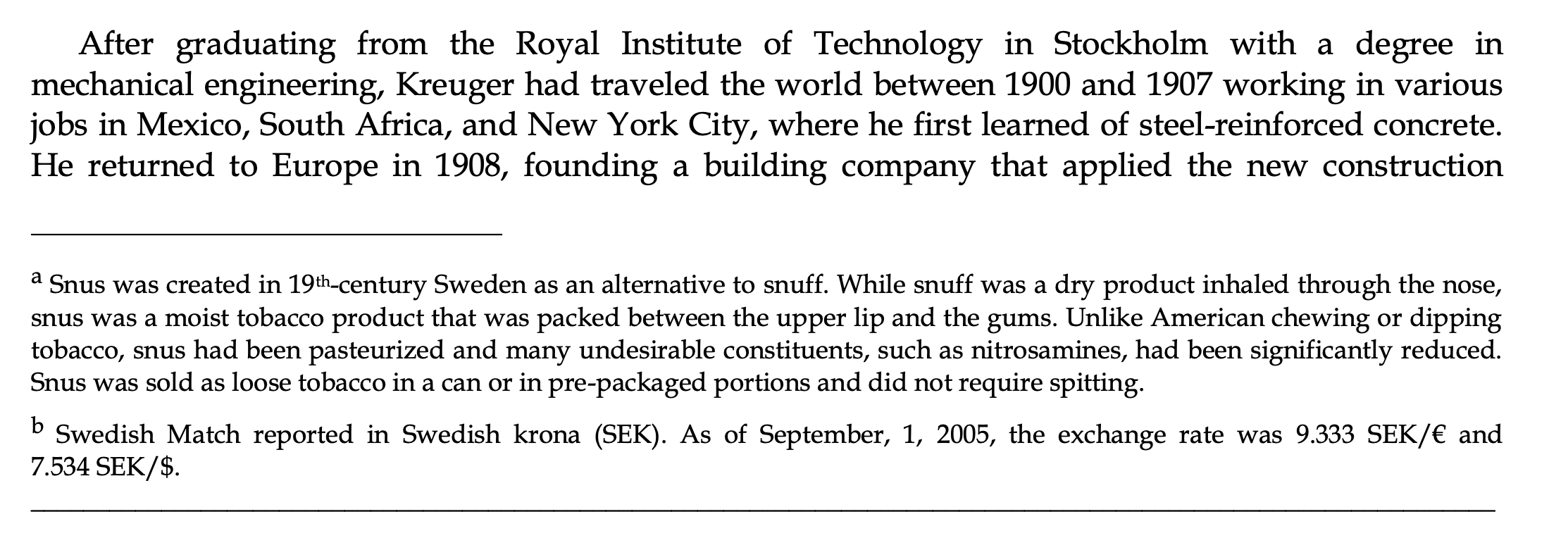

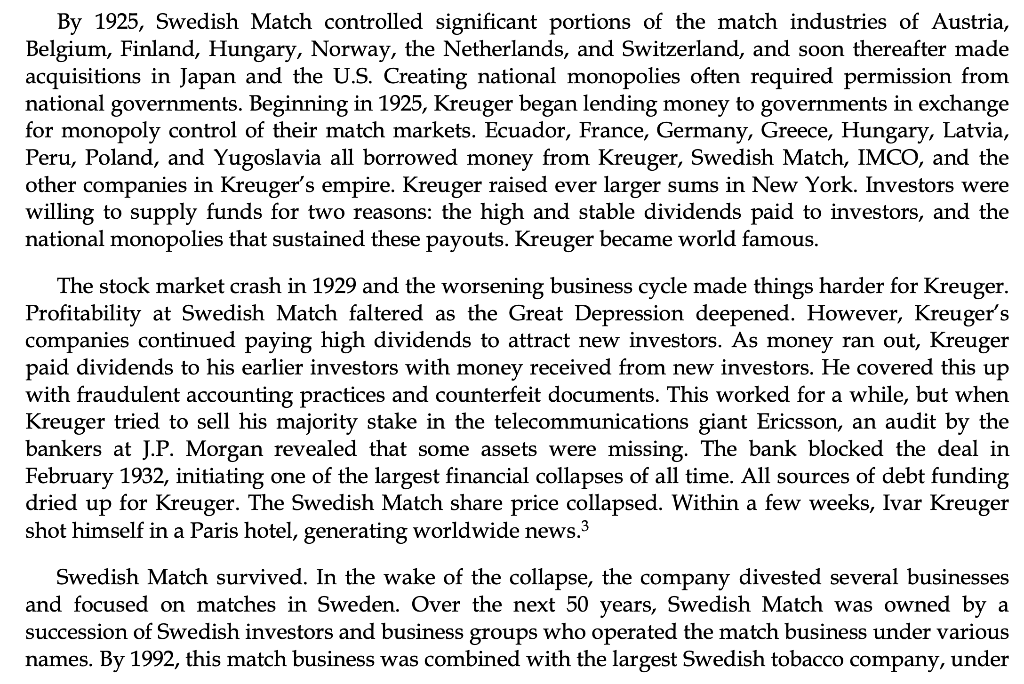

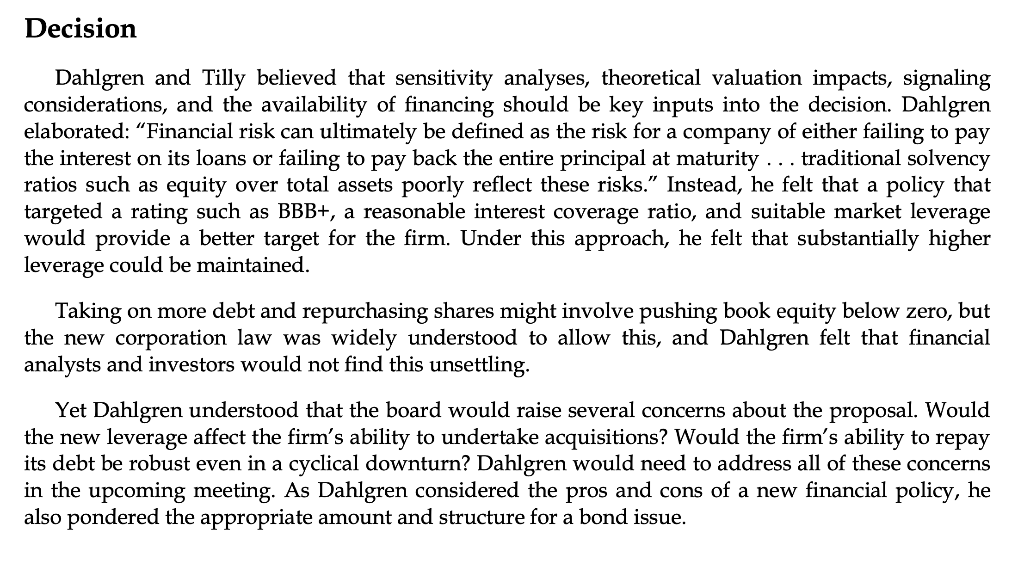

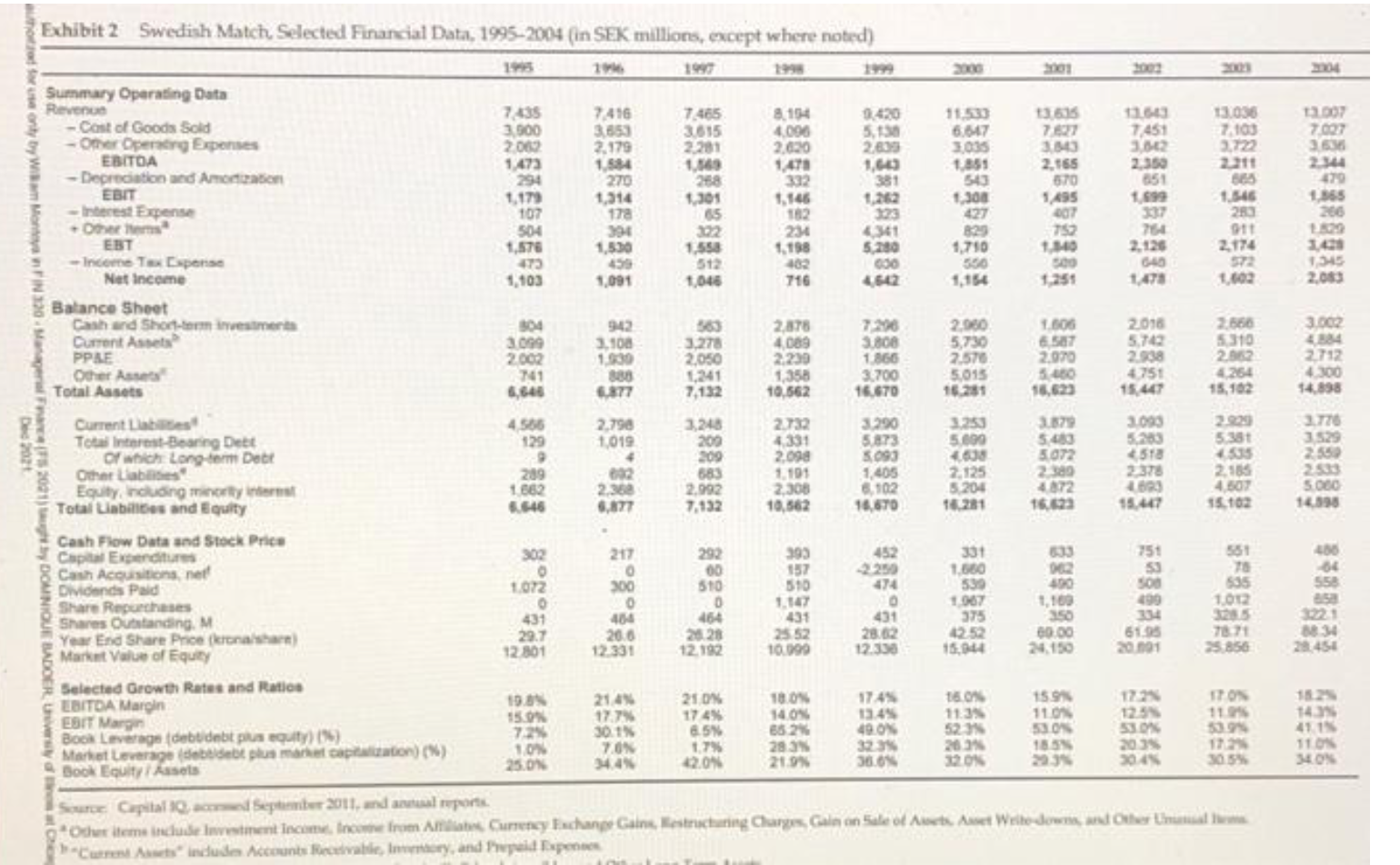

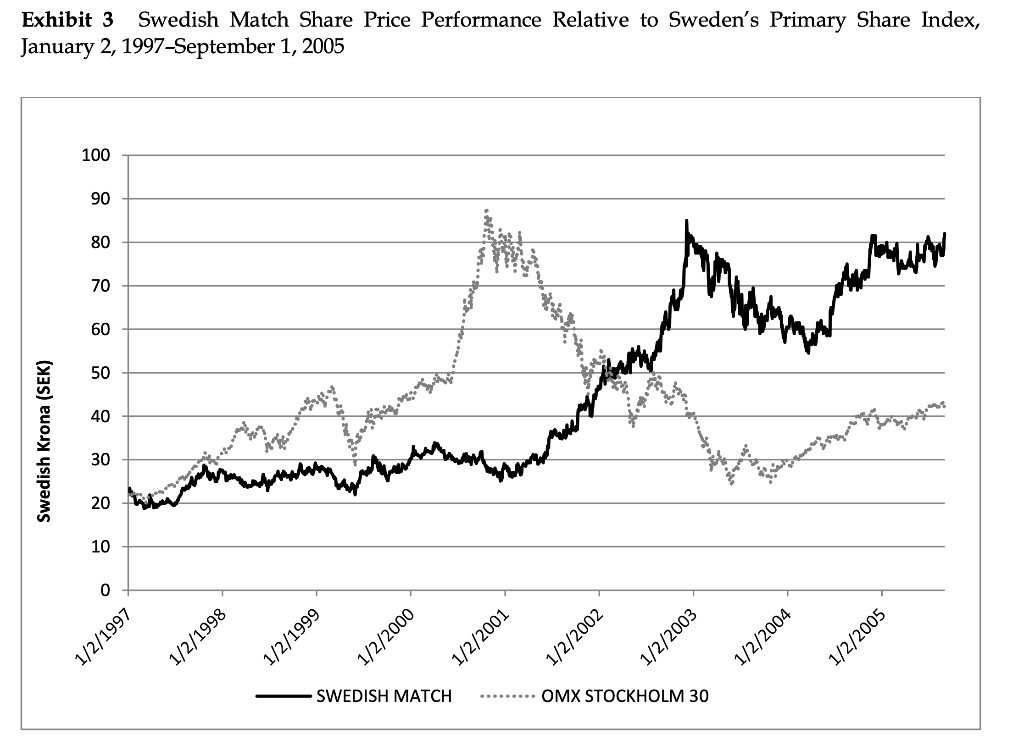

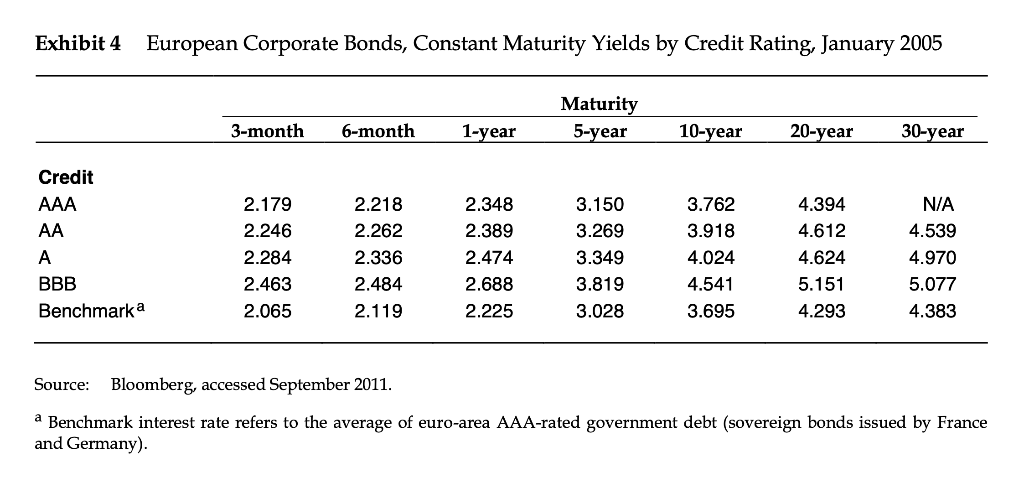

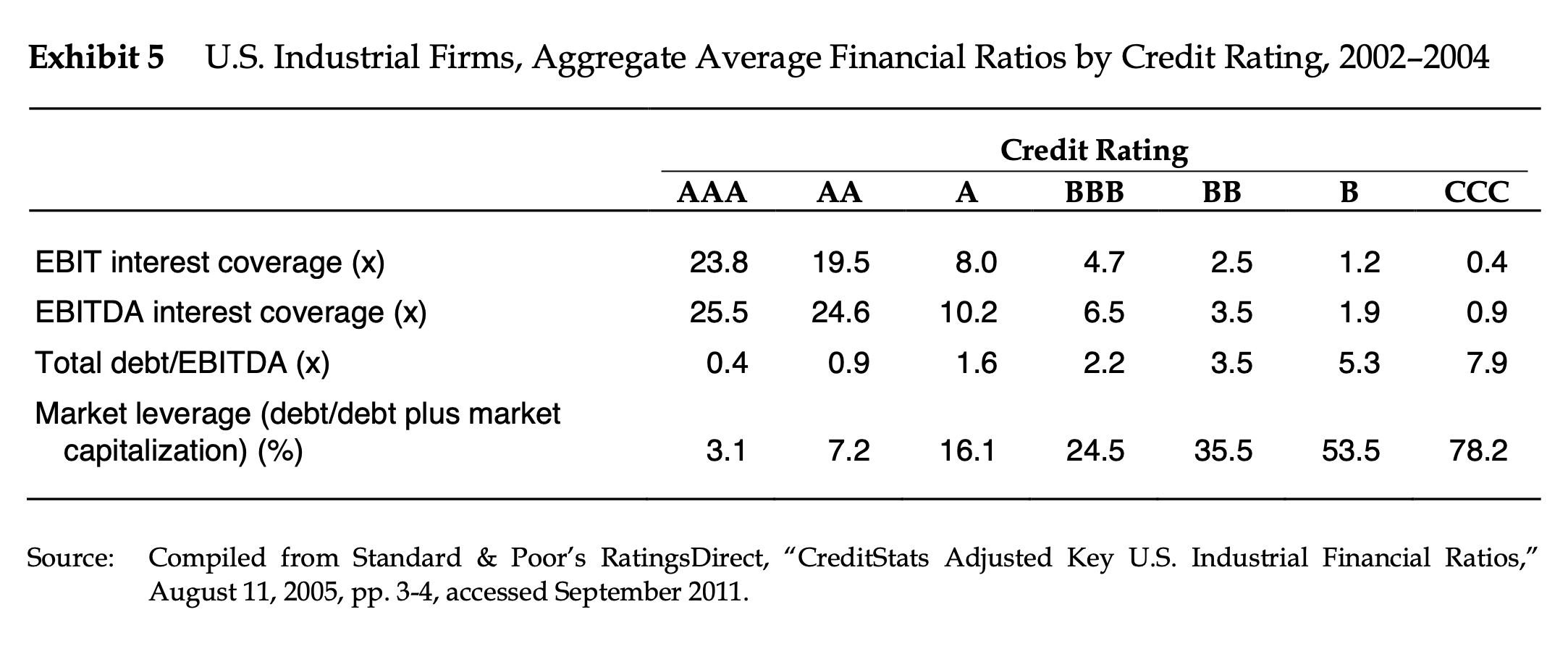

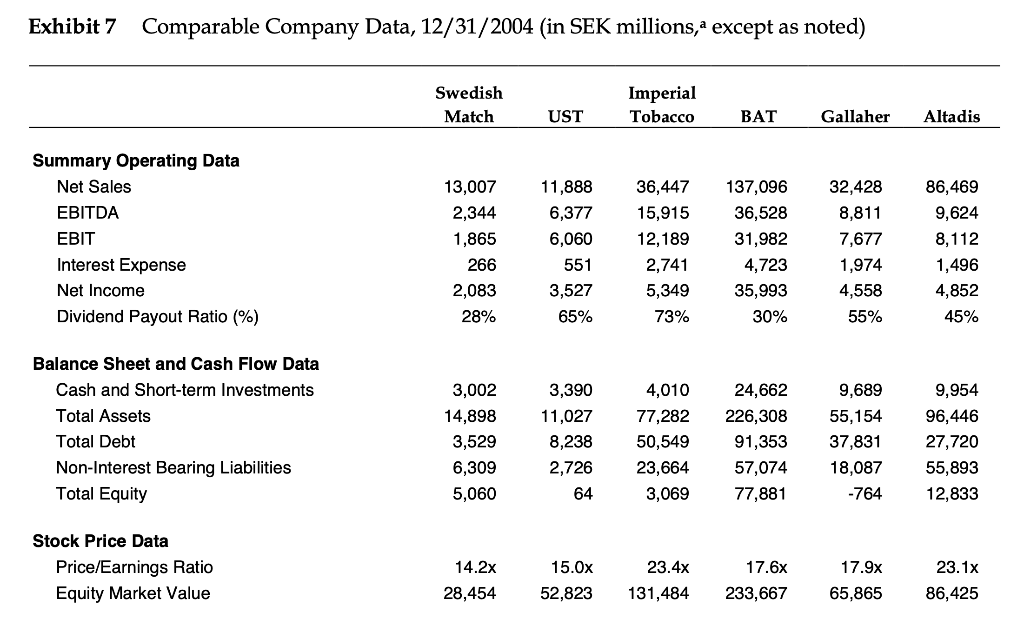

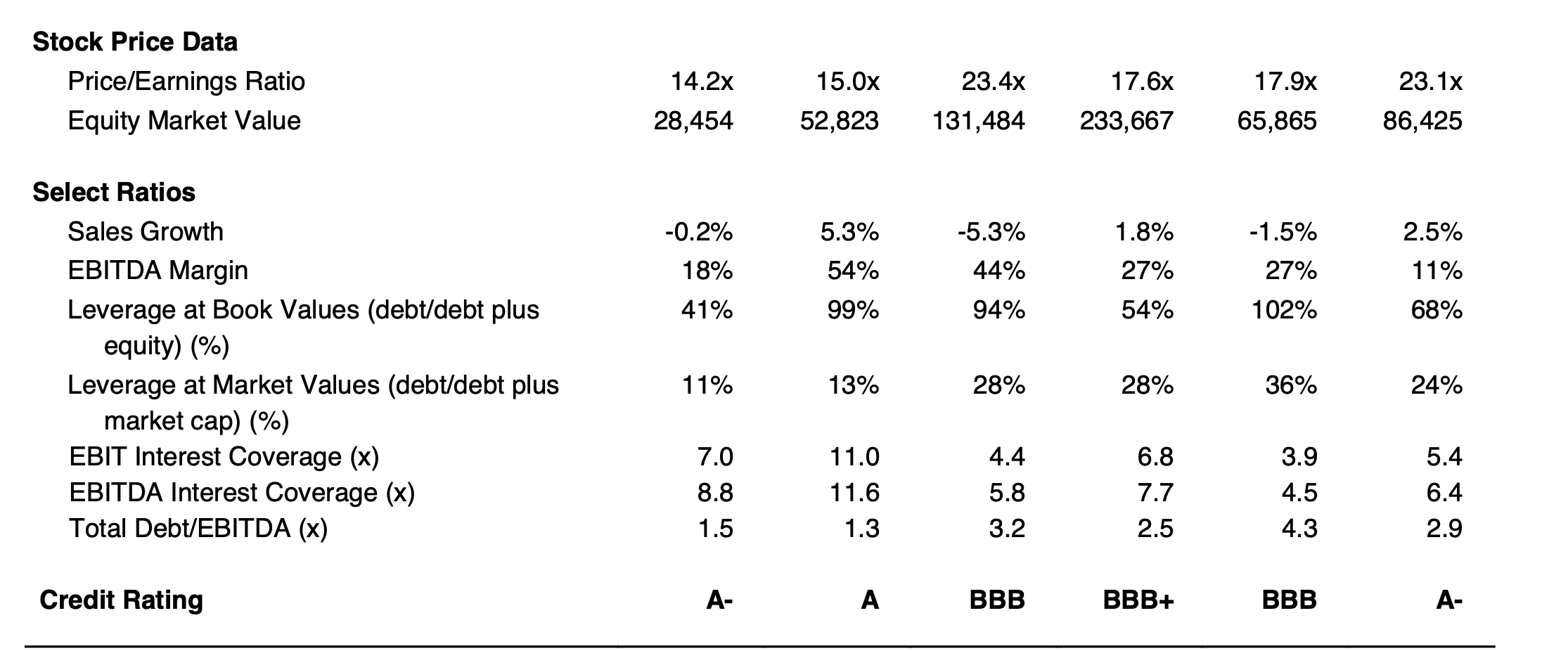

Question 5 (15 Points) Assuming that Dahlgren is correct in that Swedish Match will receive a credit rating of BBB if it moves forward with the transaction. Answer the following: - - What is the enterprise value before and after the transaction? How many shares will be repurchased and at what price? What is the share price of Swedish Match before and after the transaction? - Please make the following simplifying assumptions to answer this question: - - Use 2004 numbers to estimate the enterprise value and share price before the transaction. Assume that corporate taxes are the only market imperfection. Assume that shareholders do not anticipate the transaction before it is announced. Assume that the full proceeds from the perpetual bond issuance will be used to repurchase shares, and that all repurchases are conducted on the same day. Question 6 (5 Points) Based on your calculations from Question 5, would you recommend that Swedish Match moves forward with the transaction or not? Briefly explain your answer. A New Financial Policy at Swedish Match In early September 2005, Lars Dahlgren was weighing his options in his Stockholm office. He had recently been appointed CFO of Swedish Match, a producer of smokeless tobacco, cigars, matches, and lighters. Its most important product was a type of smokeless tobacco called snusa (see Exhibit 1). At the next meeting of Swedish Match's audit committee, Dahlgren was scheduled to present an annual review of the financial plan. Swedish Match had recently used bank loans to finance the acquisition of several cigar firms. However, these debts were being rapidly paid off, and if the firm maintained its traditional policies, its leverage- the ratio of debt to capital - would soon be very low again. Though the board did not know it yet, Dahlgren was considering a radical proposal: a substantial increase in the firm's leverage, implemented with a Euro-denominated bond issue, and combined with an aggressive program of share repurchases. This would be a sea change from the firm's more conservative financial practices. After the audit committee meeting, Dahlgren would propose the new policy to the full board in its October meeting.b Swedish Match and the Match King Swedish Match had a long and dramatic history, much of it under the leadership of Ivar Kreuger. Born in 1880, Ivar Kreuger the Match King was one of the wealthiest men in the world when he killed himself in March 1932. Kreuger had become wealthy by building Swedish Match into an international business empire comprised of national monopolies in safety matches. At the time of his death, Swedish Match had a globally dominant position, selling 66% of the world's matches.1 After graduating from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with a degree in mechanical engineering, Kreuger had traveled the world between 1900 and 1907 working in various jobs in Mexico, South Africa, and New York City, where he first learned of steel-reinforced concrete. He returned to Europe in 1908, founding a building company that applied the new construction a Snus was created in 19th-century Sweden as an alternative to snuff. While snuff was a dry product inhaled through the nose, snus was a moist tobacco product that was packed between the upper lip and the gums. Unlike American chewing or dipping tobacco, snus had been pasteurized and many undesirable constituents, such as nitrosamines, had been significantly reduced. Snus was sold as loose tobacco in a can or in pre-packaged portions and did not require spitting. b Swedish Match reported in Swedish krona (SEK). As of September, 1, 2005, the exchange rate was 9.333 SEK/ and 7.534 SEK/$. technique. The firm, Kreuger & Toll, grew to be worth SEK 1 million by 1911. Matches were the Kreuger family business, however, and Kreuger soon turned his attention there. In 1903, Sweden had 15 match companies. Six of these merged to form Jnkping och Vulcans Tndsticksfabriks AB (J&V), controlling 80% of the Swedish match market and threatening the Kreuger family company. Using contacts in the banking industry and his construction profits, Ivar Kreuger was able to raise debt to finance an expansion of the family's company. He used bank loans to merge Sweden's nine remaining match companies in 1913 into AB Frenade Svenska Tndsticksfabriks (Frenade), with Kreuger in control. During World War I, J&V sold matches to both sides of the conflict. When the Allies (initially Britain, France, and Russia) suspended J&V import licenses, Frenade, which had sold matches only to the Allied side, benefitted. In 1916, J&V was forced to merge with Frenade, forming Swedish Match. Ivar Kreuger had gained complete control over the Swedish market for matches. The monopoly in Sweden proved highly profitable, and Kreuger set out to replicate it elsewhere. As a first step, in 1917, Swedish Match acquired majority holdings in Denmark's three match companies, but this tested Kreuger's ability to borrow in Sweden to the limit. To continue expanding, Kreuger needed funding beyond the capacity of Swedish banks. In 1923, Kreuger set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York City as a way to raise money from American investors. Raising equity abroad threatened to put Kreuger in violation of Swedish laws that forbade foreign majority ownership of Swedish companies. To avoid this, Kreuger invented A and B share classes: B shares gave investors only a small percentage of the voting rights of an A share, allowing investors to buy stock in Kreuger's companies without violating Swedish law. Dual share classes of this type are still in common use around the world. Kreuger also pioneered the use of convertible securities loans that could be repaid in cash or converted to company stock.2 By 1925, Swedish Match controlled significant portions of the match industries of Austria, Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Norway, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, and soon thereafter made acquisitions in Japan and the U.S. Creating national monopolies often required permission from national governments. Beginning in 1925, Kreuger began lending money to governments in exchange for monopoly control of their match markets. Ecuador, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Peru, Poland, and Yugoslavia all borrowed money from Kreuger, Swedish Match, IMCO, and the other companies in Kreuger's empire. Kreuger raised ever larger sums in New York. Investors were willing to supply funds for two reasons: the high and stable dividends paid to investors, and the national monopolies that sustained these payouts. Kreuger became world famous. The stock market crash in 1929 and the worsening business cycle made things harder for Kreuger. Profitability at Swedish Match faltered as the Great Depression deepened. However, Kreuger's companies continued paying high dividends to attract new investors. As money ran out, Kreuger paid dividends to his earlier investors with money received from new investors. He covered this up with fraudulent accounting practices and counterfeit documents. This worked for a while, but when Kreuger tried to sell his majority stake in the telecommunications giant Ericsson, an audit by the bankers at J.P. Morgan revealed that some assets were missing. The bank blocked the deal in February 1932, initiating one of the largest financial collapses of all time. All sources of debt funding dried up for Kreuger. The Swedish Match share price collapsed. Within a few weeks, Ivar Kreuger shot himself in a Paris hotel, generating worldwide news.3 a Swedish Match survived. In the wake of the collapse, the company divested several businesses and focused on matches in Sweden. Over the next 50 years, Swedish Match was owned by a succession of Swedish investors and business groups who operated the match business under various names. By 1992, this match business was combined with the largest Swedish tobacco company, under the Swedish Match name. The firm's owner spun off Swedish Match in an IPO in 1996. At that time, the business consisted of matches and lighters, cigarettes, and niche tobacco products (cigars, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). In 1999, the company divested its remaining cigarette operations to concentrate on niche tobacco products. The firm made acquisitions in cigars, notably of General Cigars, headquartered in Virginia, in 1999. The divestment of cigarettes was a strategic move. In the Swedish market more and more people felt there were advantages to snus, a more socially accepted tobacco product, and Swedish Match was uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth. (Exhibit 2 shows summary financial data for the decade ending in 2004.) Swedish Match in 2005 By 2005, Swedish Match was a worldwide leader in smokeless tobacco products including snuff, snus, and chewing tobacco. The tobacco was sourced from carefully selected suppliers and manufactured in Sweden. These business segments accounted for 32% of 2004 sales and 72% of operating income. These products were most popular in Scandinavia and the United States. Snus had been banned in the EU since 1992, but it remained legal in Sweden. Its sale was also allowed in Norway, which remained outside the EU. The EU debated the regulatory status of snus, and a general trend emerged of increased tobacco restrictions as well as concern about possible future regulatory restrictions. However, some analysts argued that snus faced lower regulatory risks than cigarettes because the health risks were different.5 In Sweden and Norway, about one million people used snus in 2004, and Swedish Match controlled 96% of the market. In Scandinavia, popular snus brands such as General, Gteborgs Rap, Ettan, and Catch held a dominant market position. Sweden was unique in the EU with its low prevalence of cigarette smoking. Among Swedish men, the use of snus was more common than smoking cigarettes. Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer smoking cigarettes.7 Growth was also stimulated by the fact that the EU decided to remove the cancer warning from the snus can in 2002. With attractive margins and strong growth prospects, several competitors surfaced during this time on the Swedish market. The United States was the biggest growth market for smokeless tobacco products, with over 900 million cans of snuff and snus sold in the U.S. in 2004.8 In the United States, Swedish Match offered moist snuff brands Longhorn and Timberwolf and the snus brand General. The primary brands competing in the U.S. market included Grizzly, Hawken, and Kodiak, all produced by American Snuff Company, and Red Seal, Copenhagen, Rooster, and Skoal, produced by U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company. Demand for snus and moist snuff was growing in the U.S. in 2004, as more people chose smokeless tobacco over cigarettes.Red Man, Swedish Match's chewing tobacco brand, was sold only in the United States and was the market leader, with a 43% market share in 2004, and Swedish Match was hoping for further growth of snus products. 10 After smokeless tobacco, Swedish Match's most important single product was cigars, which comprised 24% of sales and 59% of operating income in 2004. Swedish Match was the world's number two cigar manufacturer, and the global leader in the premium segment of the U.S. market. 11 Swedish Match produced both machine-made and premium cigars. Premium cigars, which were made by hand, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean, accounted for 24% of Swedish Match's sales volume, and 20% of operating income in 2004. The market for machine-made cigars in the United States and Western Europe was estimated at about 13 billion cigars per year, of which Swedish Match supplied about 7%. Flavored cigars were considered the segment with the largest growth potential.12 Chewing tobacco, a stagnating product category sold mostly in the US, generated 8% of sales and 13% of operating income in 2004. 13 In addition to snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigars, Swedish Match also produced pipe tobacco, although this was a declining market (it shrunk 14% in U.S. sales volume in 2004, for example). Pipe tobacco accounted for about 9% of the company's operating income. Swedish Match maintained a 16% market share in the U.S. and profitability for pipe tobacco remained strong. Finally, matches accounted for just 11% of the company's sales in 2004 and 1% of operating income.14 Overall, Scandinavia, the U.S., and the rest of the world each represented approximately one-third of company sales. Costs matched revenues fairly well, so the net currency exposure of Swedish Match was low. Swedish Match had a conservative policy in all financial matters. At the time of the firm's IPO in 1996, management had decided to target book equity of at least 30% of assets (corresponding to interest-bearing debt over assets of 20%-40%, depending on the amount of non-interest-bearing liabilities). The firm paid high dividends and made some share repurchases. For a period, leverage had increased due to acquisitions in the cigar area. The company had an international short-term bond program (the "Global Medium Term Note Program") and a small Swedish bond program, both started in the late 1990s and by then largely paid off. The firm had a credit rating of A- from rating agency S&P (see Exhibit 5 for data on ratings). A New Financial Policy Swedish Match's financial policy was set by the board of directors (see Exhibit 6 for a list of members). In accordance with Swedish law, two labor representatives were voting members on the board. Swedish Match's president and CEO, Sven Hindrikes, appointed in 2004, was also a member of the board. Hindrikes had asked Dahlgren to propose a detailed financial policy first to the board's audit committee and then to the full board in its October 25 meeting. The board would decide on a financial policy, including how to measure leverage and what targets to apply. Several factors played into Dahlgren's sense that this was a good time to reconsider the company's financial policies. First, Sweden had recently instituted a new corporation law that allowed firms to repurchase shares even if it resulted in negative consolidated book equity for the group. Second, a continuation of the current policy would reduce leverage in the next few years. In Dahlgren's view, Swedish Match faced several potential benefits of taking on more debt. Leverage reduced the corporate income tax bill. As in the United States and many other countries, interest expenses were deductible from corporate income under Swedish tax law. The corporate income tax rate was 28%, where it was expected to remain. There were other advantages to higher leverage. Some viewed excess cash or debt capacity negatively, seeing them as potentially leading to waste and inefficiency. Further, the act of issuing new debt might be seen as a sign of strength. Institutional investors seemed to agree with a more aggressive policy. In a survey of some large owners earlier that year, several had expressed support for increased repurchases. A Citibank analyst reported,"we expect the company to buy back SEK 9-12 billion in shares by the end of 2007."15 Dahlgren also felt that the lack of explicit financial targets created unnecessary uncertainty. Finally, looking to international peers (see Exhibit 7 for selected financials), Dahlgren noticed that many of them maintained high leverage. In contrast, Dahlgren also ticked off the disadvantages of debt in his head. Net income would be lower, because some of the firm's cash flows would go to interest payments. Raising new debt might Many of the institutions that owned Swedish Match's debt and equity did not themselves pay taxes. The three largest owners were U.S. mutual fund company Wellington and two Swedish mutual fund companies: SHB/SPP Funds and Robur Funds. Several Swedish and British pension funds were also large owners. 4 also expose the firm to bond market conditions when needing to refinance. Additionally, taking on more debt would reduce financial flexibility going forward. Dahlgren also had to consider the risk to the firm's business. If the smokeless tobacco products faced more competition, the ability to pay interest payments or principal could be in doubt. A forced sale of assets, or even bankruptcy, was a possibility. Credit rating agencies would lower Swedish Match's credit rating accordingly. Dahlgren and finance vice president Joakim Tilly discussed a bond issue in the European market, given the modest size of the Swedish bond market. Based on conversations with bankers in London, they felt that bond issues below 300 million, or approximately SEK 3 billion, would be impractical and expensive to issue. Such a bond would have interest and principal repayments in euros, but it would be fairly easy to swap those payments with a bank so that Swedish Match could pay interest in SEK. The effective interest rate after swapping was expected to be similar to euro rates. Analysts expected EBITDA to be around SEK 3 billion per year in the next few years.16 Given this, Dahlgren and Tilly thought that a BBB+ rating would be sustainable under as much as SEK 4 billion of additional debt. Swedish Match's board wanted to be conservative, and thought that it was important to be prepared for a worst-case scenario where profitability dropped by as much as half. Dahlgren and Tilly thus felt it was prudent to consider a temporary drop in EBITDA to as low as SEK 1.5 billion. Swedish Match shares were currently trading at SEK 80 in Stockholm, slightly up over the year to date. Decision Dahlgren and Tilly believed that sensitivity analyses, theoretical valuation impacts, signaling considerations, and the availability of financing should be key inputs into the decision. Dahlgren elaborated: Financial risk can ultimately be defined as the risk for a company of either failing to pay the interest on its loans or failing to pay back the entire principal at maturity ... traditional solvency ratios such as equity over total assets poorly reflect these risks. Instead, he felt that a policy that targeted a rating such as BBB+, a reasonable interest coverage ratio, and suitable market leverage would provide a better target for the firm. Under this approach, he felt that substantially higher leverage could be maintained. Taking on more debt and repurchasing shares might involve pushing book equity below zero, but the new corporation law was widely understood to allow this, and Dahlgren felt that financial analysts and investors would not find this unsettling. Yet Dahlgren understood that the board would raise several concerns about the proposal. Would the new leverage affect the firm's ability to undertake acquisitions? Would the firm's ability to repay its debt be robust even in a cyclical nturn? Dahlgren would need to address all of these concerns in the upcoming meeting. As Dahlgren considered the pros and cons of a new financial policy, he also pondered the appropriate amount and structure for a bond issue. Exhibit 1 Swedish Match Snus Products SWEDISH SNS SWEDISH SNUS General General NORDIC MINT 15 PORTIONS General SWEDISH SNUS WARNING: Smokeless tobacco is addictive General Exhibit 2 Swedish Match, Selected Financial Data, 1995-2004 (in SEK millions, except where noted) 300 101 2204 3.420 2007 5.150 8.154 4.096 2.620 1.478 11.530 6.647 3,035 13.036 7.103 7465 3,615 2.281 1569 268 301 65 35 2144 7,435 3.900 2002 1.473 294 1.179 107 504 1,578 473 1,103 332 7416 3.853 2.179 1.584 270 1,314 178 394 1.530 459 1,091 12 7,451 32 2.350 551 1.699 1. 351 543 308 13.675 7627 33 2,165 570 1,495 107 75 110 500 1.251 1.146 182 SES 1.54 200 911 1.365 829 1,710 1.550 512 1,046 4341 5.280 050 4642 1.198 182 716 10 1345 640 1.478 572 1.602 304 3099 2002 7141 6,640 942 3.10 1.930 3.278 2.050 1241 7,132 2878 4089 2.230 1,350 10,562 7.296 3.800 1866 3.700 16.670 2.000 5,730 2.570 5.015 16.251 1.606 6587 2.970 5050 16.623 2018 5.70 2.938 4751 15.44 2.566 5310 2.82 4254 15.102 3.002 384 2712 4300 14.898 6.877 de by Win 20angerala 2021) DOMINIQUE BADOER UND Summary Operating Data Reve -Cost of Goods Sold -Other Opener Esperes EBITOA -Depreciation and Amation EBIT - Expense -Ohrem EBT -Income Tax Expense Net Income Balance Sheet Cash and Short-term investments Current Assets Other Asse Total Assets Current Latest Total Interest Bearing Dett of which Long-term Date Other Labas Equity, including my in Total Liabiles and Equity Cash Flow Data and Stock Price Cap Expenditures Cash Acoustions, neft Dividends Paid Share Repurchases Shares standing. M Year End Share Price (kronalar) Market Value of Equity Selected Growth Rutes and Ratice EBITDA Margin ESIT Margin Book Leverage (Gebudebitus quity (1) Market Coverage bildet plus et capitulation) () Book Equity Ass 2,790 1019 4 3093 5283